May 1, 1939: Cubs, White Sox meet to raise funds for Monty Stratton’s accident recovery

When Monty Stratton opted to take a solo hunting trip for rabbits around the family home where he grew up during the Thanksgiving holiday weekend in 1938, it was supposed to be a simple venture.

When Monty Stratton opted to take a solo hunting trip for rabbits around the family home where he grew up during the Thanksgiving holiday weekend in 1938, it was supposed to be a simple venture.

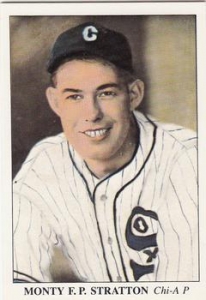

But the hunt around the expansive Texas farm quickly turned tragic, when the 26-year-old Chicago White Sox pitching ace failed to secure the safety while reholstering his .22-caliber pistol and accidentally shot himself in the right leg. At a nearby hospital, the bullet was removed, but gangrene set in the next morning and his right leg was amputated.

Thus ended the career of one of the American League’s most promising young pitchers. An All-Star in 1937, Stratton was expected to anchor the White Sox rotation for years to come. He instead took on a coaching role with the team but did get one last chance to throw from the mound at Comiskey Park after the accident.

The White Sox and Chicago Cubs gathered for an exhibition game in Stratton’s honor on May 1, 1939, and Stratton tossed out the ceremonial first pitch before his teammates scored early against Dizzy Dean and dispatched the reigning National League champion Cubs, 4-1. A crowd of 25,594 was on hand and helped raise $29,875.251 to benefit Stratton’s recovery in a game that was “something more than a gesture,”2 and was postponed from its original date of April 17.3

Even the players, umpires, ushers, and newspaper reporters paid an admission fee that went toward Stratton’s fund, and the R.G. Lydy Parking Company turned over all the revenue it generated during the game to add another $771.50, while radio stations WGN, WCFL, and WJJD also combined to add almost $1,000 to the total. The final $30 contributed to the fund came from a trio of criminals, who were found stealing tickets to the benefit game. The three men—Sol Guttenplan of Brooklyn, Louis Silver of New York City, and Russell Higgins of Detroit—were each assessed a $1 fine by Chicago’s Judge J.M. Braude, with the stipulation that they contribute $10 to Stratton’s benefit fund.4

Dean, who famously came to the Cubs from the St. Louis Cardinals on April 16, 1938, in exchange for a near-record $185,000 and three players,5 had thrown just two innings in spring training and none in the Cubs’ first 10 games of the season. He likely wasn’t ready to pitch, but despite his sore arm, Dean was given the start in an effort to boost attendance.

While both teams made modest scoring threats early in the game, it was in the third inning that Cubs shortstop Dick Bartell kicked off a White Sox rally by committing an error for the second straight inning. Joe Kuhel reached second after Bartell’s throw of a routine grounder sailed into the Cubs’ dugout. Gee Walker flied out for the second out of the inning, but Luke Appling, Eric McNair, Larry Rosenthal, and Mike Kreevich hit successive singles for three unearned runs.

Kuhel doubled with two outs in the fourth and scored on Walker’s single, ending Dean’s outing.

“There’s no use kidding myself. [My arm] really hurts,” said Dean, who wouldn’t appear in a regular-season game until May 16. “It’s sore as the deuce up here [at the shoulder].”6

Rookie Kirby Higbe relieved Dean and surrendered just one hit, a double by Ken Silvestri in the sixth. The only other baserunner came in the seventh, when McNair reached on a dropped fly ball. The strong showing was the start of a solid stretch for Higbe, who allowed just four hits in his next six outings over the next 2½ weeks. He did walk 12 batters in those 16 innings, and by the end of the month, Higbe and his lack of control were traded to the Philadelphia Phillies.7

In the seventh, the Cubs tallied their lone run. Phil Cavarretta smacked a one-out single to right, and Bob Garbark poked a single to center. Bartell reached on a grounder that advanced Cavarretta to third and forced Garbark out at second, and Higbe drove in the run with a single to center.

Otherwise, John Whitehead was sharp for the White Sox. He struggled early in the season, allowing 12 runs on 24 hits in two starts and a relief appearance before the benefit game, and he was only slated to pitch the first three innings of the exhibition. Art Herring, who was back in the major leagues for the first time since 1934,8 and newly acquired Eddie Smith9 were both scheduled to throw three innings, but since Whitehead was cruising, manager Jimmy Dykes kept him in the game.

The benefit game was originally scheduled as the final tune-up before Opening Day, but it was postponed by rain. It took some rearranging of the schedule to make the May 1 date work, but there was little trouble making it happen. The date was open for the Cubs between the last game of a home series against the St. Louis Cardinals and the opening game of a series at Philadelphia against the Phillies.

The White Sox were scheduled to play the final game of a series against the St. Louis Browns on May 1, but St. Louis President Don Barnes agreed to postpone the scheduled game and bought $50 in tickets that were sent to a Chicago orphanage.10 That game was made up as part of a doubleheader on September 7, which the White Sox swept with 8-4 and 11-4 victories.

Stratton hoped his ceremonial first pitch wouldn’t be the last ball he fired from a major-league mound, and Dykes supported his effort to return to the big leagues, even if the odds were stacked against him. One aspect that worked in Stratton’s favor was that his still-healthy left leg was more crucial to his delivery.

“You see, he can rear back on that artificial leg, and when he bends forward to throw, his weight will be on his left leg, his natural pivot leg, when going through with his pitch,” Dykes said. “Monty is determined, and I think he can do it. He is only [26] and has plenty of years before him. Time will tell.”11

Stratton never appeared again in the majors, but he was able to make a minor-league comeback. After World War II ended, he pitched for the Sherman Twins of the Class C East Texas League and recorded 18 victories. Had the war not forced so many minor leagues to suspend operations or fold completely, Stratton’s comeback likely would have come much sooner. He continued playing until 1950, when he was 38 years old.

His life’s journey was adapted into a motion picture, The Stratton Story, in 1949. The film starred James Stewart and June Allyson, the same duo who played the leading roles in the Glenn Miller Story, a 1954 biographical film about the life of the famed big-band leader and trombonist.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Ray Danner and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com, Stathead.com, and Retrosheet.org websites for pertinent material and the box scores noted below. He also used information obtained from game coverage by the Chicago Tribune. He also consulted the SABR BioProject biography of Monty Stratton, which was written by Gary Sarnoff.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/99862544/monty-stratton-benefit-box-score/

Notes

1 In addition to the money, which Stratton used to pay off the mortgage for his family farm and placed the remainder into investment funds, he received an automobile from former White Sox teammate Tony Piet, who became a car dealer after retiring from baseball following the 1938 season.

2 Untitled editorial, Mattoon (Illinois) Daily Journal-Gazette and Commercial-Star, May 3, 1939: 4.

3 Due to inclement weather, the entire four-game City Series between the Cubs and White Sox was postponed, leaving both teams without a final tune-up before Opening Day on April 18. The White Sox fell 6-1 in Detroit, while the Cubs were hosting the Cincinnati Reds and had to cancel the series because of continued poor weather. The Cubs finally got a game in after traveling to St. Louis for an April 21 matchup against the Cardinals.

4 Associated Press, “Fines Raise Stratton Fund to $29,875 Total,” Decatur (Illinois) Review, May 4, 1939: 10.

5 The Cubs also gave up Curt Davis, Clyde Shoun, and Tuck Stainback in the deal. The only player ever sold for more than $185,000 was Joe Cronin, who was purchased by the Red Sox for $225,000 in 1934 in a deal that also saw them send the Washington Nationals shortstop Lyn Lary.

6 Charles Dunkley (Associated Press), “Dean’s Arm ‘Sore as the Deuce’ After Exhibition Contest,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, May 2, 1939: 19.

7 Higbe went to the Phillies along with Ray Harrell and Joe Marty in exchange for Claude Passeau on May 29. After he led the National League in strikeouts and earned an All-Star selection in 1940, the Phillies traded him to the Brooklyn Dodgers for $100,000 and Bill Crouch, Mickey Livingston, and Vito Tamulis.

8 Herring pitched for the Detroit Tigers from 1929 to ’33 and the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1934. He spent 1935 with the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League and the next four seasons with the St. Paul Saints of the American Association before making the White Sox roster in 1939. Herring also spent 1940-44 with the Saints before rejoining the Dodgers in August 1944.

9 On April 27 Smith was selected off waivers by the White Sox from the Philadelphia Athletics.

10 George Kreker, “Fans’ Fare,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald and Review, May 2, 1939: 9.

11 “Baseball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 7, 1939: 34.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 4

Chicago Cubs 1

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.