October 2, 1919: Reds take advantage of Lefty Williams’s wildness in Game 2

After the Cincinnati Reds stunned the “baseball dope” in Game One of the 1919 World Series by knocking out Chicago ace Eddie Cicotte, rumors were flying about the White Sox’ uncharacteristically poor performance.

After the Cincinnati Reds stunned the “baseball dope” in Game One of the 1919 World Series by knocking out Chicago ace Eddie Cicotte, rumors were flying about the White Sox’ uncharacteristically poor performance.

The whispers would only grow louder after Game Two.

Because baseball’s powers-that-be had voted on using an experimental best-of-nine format instead of the usual seven games, the White Sox had to rely even more heavily on their two star pitchers, Cicotte and Lefty Williams. Their thin pitching staff couldn’t afford another early loss in the World Series.

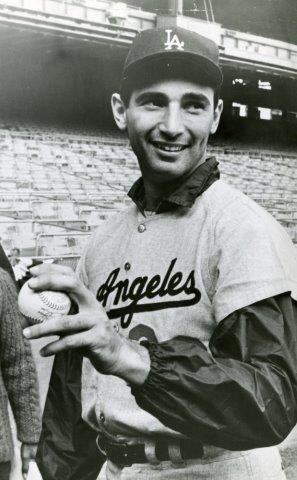

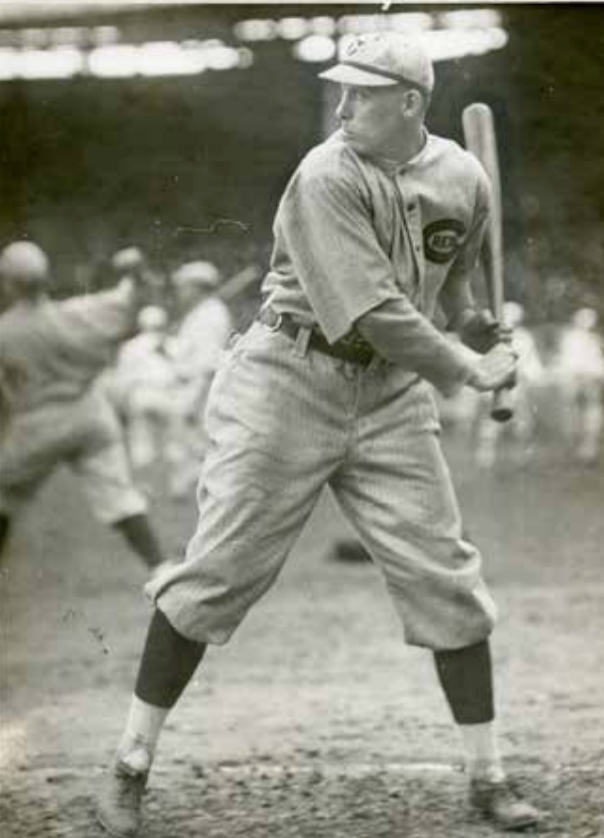

Williams, a 26-year-old southpaw in his fourth full season, had posted career highs with 23 wins and a 2.64 ERA in the regular season. Before the Series, White Sox manager Kid Gleason raved about his reputation as a control artist: “It isn’t often that a batter gets a ball in the groove when Williams is pitching. He’s always on the edge of the plate.”1 The Reds, however, were the most patient team in the National League, leading all teams in on-base percentage at .327.

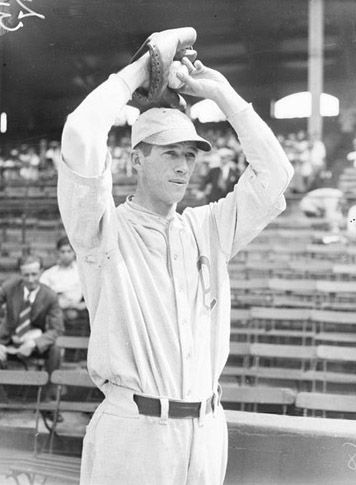

Opposing Williams on the mound was veteran left-hander Slim Sallee, who also had set personal bests with a 21-7 record and a 2.06 ERA. Sallee had faced the White Sox twice back in the 1917 World Series while with the New York Giants, but he lost both starts. He would get his revenge on this warm Thursday afternoon in Cincinnati.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

The first three innings were highlighted by the Reds’ stellar defense as Sallee held the Sox scoreless. In the first shortstop Larry Kopf made a lunging stab of Buck Weaver’s line drive on a hit-and-run play and then easily doubled up Eddie Collins at first base. In the third center fielder Edd Roush and left fielder Pat Duncan both made nice running catches. Sallee escaped another jam in the fourth when first baseman Jake Daubert threw out Weaver at the plate.

Meanwhile, Williams faced the minimum nine batters and didn’t allow a hit through three innings. The fateful fourth inning proved to be his undoing, just as it had for his teammate Cicotte in Game One.

The bottom of the fourth began with a leadoff walk to Morrie Rath on a full count. After a sacrifice bunt moved Rath to second, Williams allowed another base on balls, to Heinie Groh. Catcher Ray Schalk, concerned with his pitcher’s sudden loss of control, went out to settle him down. After Williams threw two balls to Roush, the NL batting champion lined a single into center field to score Rath with the Reds’ first base hit.

The White Sox caught a break when Roush was thrown out on a delayed steal for the second out. But Williams walked Duncan, his third free pass of the inning. The light-hitting Kopf then broke the game open, jumping on Lefty’s first pitch for a triple to the temporary fence in left-center field. Groh and Duncan both scored to make it 3-0.

Williams would go on to walk six Reds hitters, tying his career high. All four of the Reds’ runs in the game were scored by players who reached base via walks. Afterward, the Chicago Tribune’s Irving Sanborn summed up the consensus opinion in the press box that Williams’s wild pitching was “almost criminal.” The Reds “could have won with toothpicks for bats,” he added.2

Home-plate umpire Billy Evans had a less damning opinion, which he recalled a year later when it was revealed that Williams had been indicted for conspiring with his teammates to fix the World Series:

“Of the four men walked, Williams didn’t throw one ball that would have been classified as a real bad pitch. Every ball delivered was at the waistline, and not one of them was over six inches inside or outside, and most of them [were] much less than that. There wasn’t a ball around the shoe tops or above the shoulders, so that even a spectator in center field would have known it was a ball. … I regarded the loss of that game at the time as one of the hardest bits of luck I ever saw a pitcher go up against.”3

For his part, Williams insisted that he wasn’t pitching to lose. “I didn’t have to,” he told a Chicago grand jury 11 months after the World Series. “I was a little nervous … [but] I just pitched naturally and walked the fellows. After that they made base hits.”4

Williams’s hard luck — or his lack of effort, given the circumstances — was counteracted by Slim Sallee’s quick, tidy performance that relied on the Reds’ strong defense.

In the sixth, Edd Roush made the play of the game, running down Happy Felsch’s long blast to the 420-foot wall in deep center field to end the inning and save a run or possibly two from scoring. Roush was “cheered all the way to the Reds’ dugout” by the hometown fans.5

The Reds added another run in the sixth on a single by Greasy Neale to score Roush. Chicago’s only scoring came in the seventh, when Schalk singled home Swede Risberg, then came all the way around on Neale’s throwing error from right field. Sallee went the distance, allowing 10 hits and one walk to go with the two unearned runs.

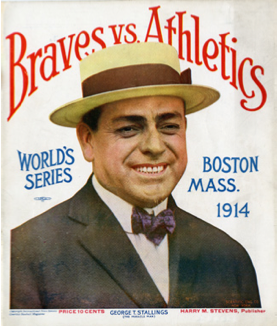

Cincinnati had stunned the baseball world by winning the first two games at home against the favored White Sox. Manager Pat Moran, already known as the “Miracle Man” for bringing home the Philadelphia Phillies’ first pennant in 1915 and now with the Reds flying high, was supremely confident in victory. “We have beaten Cicotte and Williams and have nothing to fear from the other pitchers of [Kid] Gleason’s staff,” he said.6

Gleason credited the Reds defense for making the difference. “Fielding that happens only [once] in a lifetime robbed us of enough runs to win. Roush is a marvel in the outfield and my players all give him credit for his work,” said the White Sox manager.7

But astute observers were growing more suspicious of Chicago’s noticeably lackluster play. Cleveland Indians manager Tris Speaker, who was hired to write a column for the Cleveland Plain Dealer during the World Series, repeatedly called out the White Sox’ poor execution of basic fundamentals and noted that Williams was “wilder than I ever saw him before.”8

Something was indeed wrong with the White Sox. But the Reds still had a World Series to win — and now they needed just three more wins to do it.

This article was published in “Cincinnati’s Crosley Field: A Gem in the Queen City” (SABR, 2018), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseballl-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Kid Gleason, “James and Kerr Will Be Able to Back Up Cicotte and Williams Successfully, if Necessary, Their Pilot Writes,” Washington Post, September 28, 1919.

2 I.E. Sanborn, “White Sox Crushed Again, 4 to 2,” Chicago Tribune, October 3, 1919.

3 Billy Evans, “Crooked Work Fools Evans in Series of 1919,” Chicago Tribune, December 19, 1920.

4 William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 57-59.

5 George S. Robbins, “Williams Fails to Hold National Leaguers in Check,” Chicago Daily News, October 2, 1919.

6 “Pat Jubilant Over Team’s Second Win,” Boston Herald, October 3, 1919.

7 Ibid.

8 Tris Speaker, “Tris Speaker Surprised at Form Chicago Shows as World Series Opens,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 2, 1919. Speaker was extremely outspoken in his newspaper columns about the White Sox’ poor play during the World Series. For more, see Bruce Allardice, “Speaker: ‘Something Phony About It All’,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, June 2015.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 4

Chicago White Sox 2

Game 2, WS

Redland Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.