September 6-10, 1939: Baltimore Elite Giants top Newark Eagles in Negro National League playoffs

In 1939 both the Baltimore Elite Giants and the Newark Eagles were “resolved to improve on the results”1 of the previous season. The 1938 season had been the maiden campaign for Baltimore in the Negro National League II (NNL2), as the franchise had moved up the road from Washington.2 Under player-manager George Scales, the Elite Giants went 26-23-3 in that first season in Baltimore, good for third place in the NNL2 standings but 12½ games behind the first-place Homestead Grays. The Grays had started a string of nine consecutive seasons in which they topped the league standings in 1937. In fifth position in 1938 were the Eagles (17½ games back), guided by Dick Lundy, who was in his second season as their skipper.3

In 1939 both the Baltimore Elite Giants and the Newark Eagles were “resolved to improve on the results”1 of the previous season. The 1938 season had been the maiden campaign for Baltimore in the Negro National League II (NNL2), as the franchise had moved up the road from Washington.2 Under player-manager George Scales, the Elite Giants went 26-23-3 in that first season in Baltimore, good for third place in the NNL2 standings but 12½ games behind the first-place Homestead Grays. The Grays had started a string of nine consecutive seasons in which they topped the league standings in 1937. In fifth position in 1938 were the Eagles (17½ games back), guided by Dick Lundy, who was in his second season as their skipper.3

For the Elite Giants and Eagles, their resolutions for the 1939 season came true. Although Baltimore’s overall record for 1939 was 29-25 (their NNL2 record was 21-23), the Elite Giants “ran away with the second half championship.”4 In fact, they had been in first place in early June, “a position they clung to until the last week of June, when their fortunes headed south,”5 and the team finished the first half of the season in third place. However, the Elite Giants then posted the best mark in the NNL2’s second half, which began in July.

The Newark Eagles had finished the 1939 season in second place with a record of 32-23-1. They played consistently; although they were not quite good enough to win either half of the season, they were strong enough to stay in the mix for the playoffs.

Before the 1939 season had begun, the New York Yankees had offered the Jacob Ruppert Memorial Trophy, named after their recently deceased team owner, to the Negro National League II team that won the most games at Yankee Stadium each year. Yankees President Edward Barrow now had established a tournament to honor Ruppert that consisted of five four-team doubleheaders to be played on Sundays at Yankee Stadium. After all the games had been played, the team with the best overall record would receive the trophy and $500.6 It was hardly a selfless gesture since the Yankee organization was profiting from the games, too. They charged teams between $2,000 and $3,000 per date to play at Yankee Stadium.7

The second such doubleheader took place on July 2. The Eagles handily defeated the Philadelphia Stars 8-1, while the Elite Giants blanked the New York Black Yankees, 4-0. Baltimore’s “three-run rally in the ninth clinched the outcome.”8 Before the games, the Negro National League paid tribute to its Hall of Fame. According to the New York Times, “Pioneers of the sport in Negro circles [were to] be guests of honor at the games.”9 The nominations for the Hall of Fame included Newark’s first baseman Mule Suttles and shortstop Willie Wells.10

As the season progressed, a decision was made to award the trophy to the winner of the Negro National League II pennant. Normally, the winners of each half of the season competed in a two-team playoff series to determine the pennant winner. Under a new format introduced in 1939, the four teams (out of the six total) that had won the most games throughout the entire season would compete in a set of playoff series. From a revenue standpoint, more teams in the playoffs meant more games played, and “more games meant more gate receipts.”11 In any event, under the expanded playoff format, the top-seeded Homestead Grays faced the fourth-seeded Philadelphia Stars, while the second-seeded Newark Eagles took on the third-seeded Baltimore Elite Giants.12 Both series were scheduled for early September.

The Newark Eagles came into the series against Baltimore having slugged 32 home runs in 56 games during the regular season. Mule Suttles and Ed Stone paced the team with seven homers each. The Elite Giants had played only 44 games but had swatted 12 homers, led by Henry Kimbro and pitcher Bill Byrd (three homers each). Additionally, each ballclub had stars who had played in the East-West All-Star Game on August 6 at Comiskey Park in Chicago.13

Game One: September 6, 1939

Newark Eagles 8, Baltimore Elite Giants 6

Ruppert Stadium, Newark, NJ

Game One took place on September 6 at Ruppert Stadium in Newark. The contest was characterized, and eventually decided by, the long ball. Newark’s Bob Evans and Baltimore’s Emery Adams had the starting mound duties. Evans had been playing in Newark since 1934, first for the Newark Dodgers and then, beginning in 1936, for the Eagles. The 6-foot-5 right-hander was a workhorse for his first five seasons, but in 1939 he had made just four appearances on the mound, pitching 19 2/3 total innings. His 1.780 WHIP contributed to a 7.32 ERA. Conversely, this was Adams’s first season with Baltimore. He was also a righty but stood only 5-feet-8, and he had pitched the previous three seasons for the Memphis Red Sox. In 1939 Adams had five appearances (two starts).14 Although he sported a 2-0 record, his ERA was 5.85, and he had allowed more walks than strikeouts; his strikeout-to-walk ratio was 0.86.

Baltimore jumped ahead with a run in the top of the third, and then the Elite Giants exploded for four more runs in the fourth, sending Evans to the showers. Over the next three innings, the Eagles “pulled an almost certain defeat ‘out of the fire.’”15 In the bottom of the fourth, Newark rookie Freddie Wilson reached first with a hit. Suttles, already known as “one of the greatest power hitters in Negro League history,” [16 clouted a home run into the left-field stands. The Newark Star Eagle reported that the blast traveled 425 feet.17

Max Manning, a 20-year-old rookie, relieved Evans to start the fifth and “held the Giants effectively.”18 In the home half of the fifth, Wilson homered into the center-field stands with two men aboard to tie the game. Suttles followed him with a solo shot over the left-field wall, his second home run in as many innings. This gave the Eagles the lead, and now it was Baltimore’s turn to make a pitching change. Byrd was summoned to the mound to relieve Adams.

Byrd pitched for the Baltimore Elite Giants from 1938 through 1948 (and for the Cleveland Red Sox and the Columbus and Washington Elite Giants before that).19 The right-hander later led the league in wins three times (in 1942, 1945, and 1948)20 and in ERA once (1941). His 1939 statistics included a 7-2 record and a 3.32 ERA in 76 innings pitched. As a member of the Baltimore teams, he appeared in seven different East-West All-Star Games; he started both All-Star Games in 1939 for the East squad.21 Byrd is also known as “the last Negro league pitcher to legally throw the spitball.”22 On top of that, in 1939 he batted .378 and had an OPS of 1.086.

Newark padded its advantage in the bottom of the sixth after 42-year-old Biz Mackey singled and advanced a base on Manning’s sacrifice. Mackey had begun the season with Baltimore but after 13 games with the Elite Giants, was sold to the Eagles.23 Joe Eckles doubled, plating Mackey, and Eckles later scored on Dick Seay’s single to make it an 8-5 game in favor of Newark.

Manning cruised through the rest of the game as he fanned two Baltimore batters and yielded only four hits, although the Elite Giants did get another run in the seventh. The Eagles battered Adams and Byrd for 11 hits that included three homers. Suttles added a double to his two round-trippers to lead the Eagles’ assault, driving in three runs. Wilson, Seay, and Mackey each contributed two hits as well. Baltimore pounded out 13 hits total, but most of them came off Evans in the first four frames. Newark’s 8-6 victory was an exciting start to the playoff series.

| Baltimore | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 0 | ||

| Newark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | x | 8 | 11 | 0 |

WP: M. Manning, LP: E. Adams.

Game Two: September 9, 1939

Baltimore Elite Giants 11, Newark Eagles 3

44th and Parkside, Philadelphia

The second game of the series was played three days later in Philadelphia, at the 44th and Parkside ballpark. The Eagles still played as the home team. Baltimore again outhit the Eagles, and this time, the Elite Giants prevailed. Jonas Gaines started for Baltimore and pitched a complete game, scattering seven hits. In six appearances during the regular season, he had made five starts and tossed four complete games. Future Hall of Famer Leon Day started for Newark. He had tied for the league lead in starts in 1939 (with Philadelphia’s Jim Missouri – each had 11), winning seven of 10 decisions with seven complete games. However, in this playoff game, he was soon replaced by Evans, in part because he walked five batters during his brief time on the mound.24

Baltimore scored two runs in the top of the first. Felton Snow’s two-out double drove in both Kimbro and Sammy Hughes. Hughes later blasted a solo home run for Baltimore in the second inning, and Baltimore added single tallies in each of the next two innings as well. In the sixth, the visitors scored four more times to put the game out of reach. Each team scored twice in the eighth inning. Suttles hit his third homer of the series, a two-run round-tripper, to prevent Newark from being shut out. The Eagles added a run in the bottom of the ninth on Mackey’s single that scored Wilson.

The Newark defense made five errors in the game, which contributed to the rout.25 Hughes and Red Moore led the Elite Giants with three hits each, and half of Baltimore’s 12 hits went for extra bases; in addition to Hughes’s homer, the Elite Giants hit five doubles. Newark’s leadoff batter, future Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, had done his utmost for the losing team on this day and joined Wilson and Mackey as Newark batters who had two hits each.

| Baltimore | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 0 | ||

| Newark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

WP: J. Gaines, LP: L. Day.

Game Three: September 10, 1939

Baltimore Elite Giants 7, Newark Eagles 3

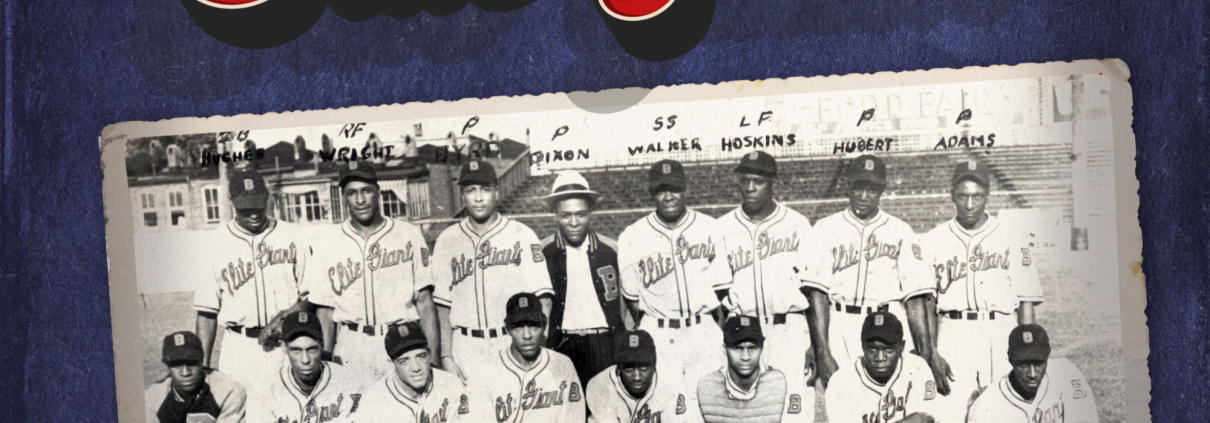

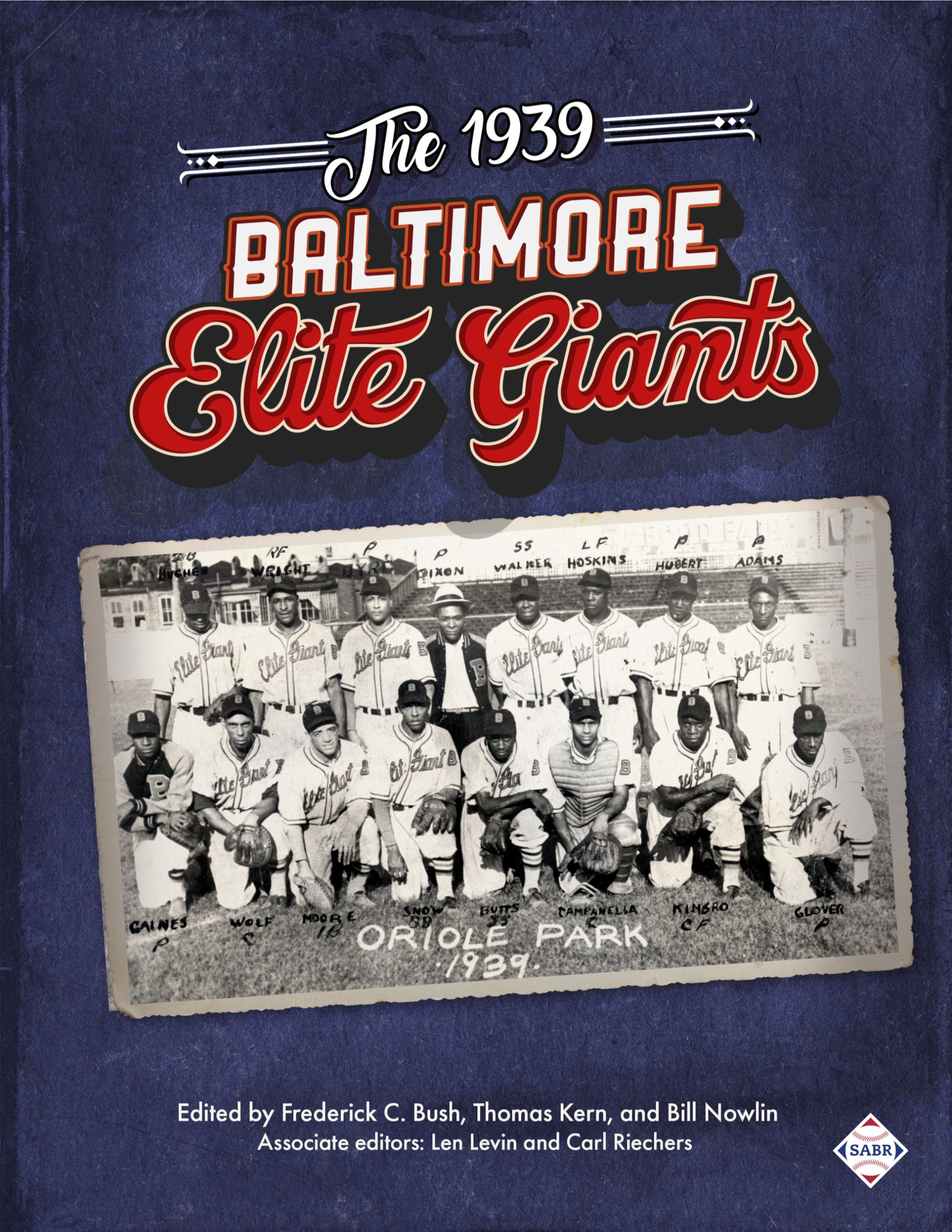

Oriole Park, Baltimore

With the series tied at one game apiece, the two ballclubs headed to Baltimore for a game to be played on Sunday, September 10, at Baltimore’s Oriole Park, as the first game of a scheduled doubleheader. Newark sent rookie Harry “Big Train” Cozart, its “six feet four-inch chucker,”26 to the mound. Baltimore countered with Byrd. Each team hoped to “continue their campaign for a place in the finals of the Negro National League playoffs.”27

Byrd held the visiting Eagles scoreless through the first four innings. Meanwhile, the Elite Giants tallied twice in the bottom of the third. Byrd helped his own cause with a solo home run while Kimbro doubled and was driven in by Hughes. Baltimore added two more runs in the fourth for a 4-0 lead. Newark responded by scoring once in the fifth and then twice in the sixth, with one run coming on Ed Stone’s homer, to make it a one-run game.

Baltimore got both runs back in the bottom of the sixth and added a final run in the eighth to win the game, 7-3. In spite of heavy hitting by both sides, the two starters pitched complete games. For the third consecutive game, the Elite Giants put up double-digit hits (10), and the Eagles banged out 13 hits in the losing cause.

| Newark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Baltimore | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | x | 7 | 10 | 1 |

WP: B. Byrd, LP: H. Cozart.

Game Four: September 10, 1939

Baltimore Elite Giants 5, Newark Eagles 2

6 innings

Oriole Park, Baltimore

At some point, a decision was made to play a doubleheader, perhaps to expedite determining a winner of this series that was to go a maximum of five games. The third game had taken 2 hours and 35 minutes, so the two teams began to play Game Four in the late afternoon. Willie Hubert started for Baltimore while Manning, who had pitched in relief in Game One, started for the Eagles.

Wells led off the game for Newark and reached on an error by third baseman Snow. Wells used his speed to steal a base and came around to score on catcher Roy Campanella’s subsequent throwing error. Two errors had led to a run. In 1939 future Hall of Famer Campanella was just 17 years old, but he already was playing in his third season with the Elite Giants. Campanella credited Mackey as his mentor and catching coach, saying, “He just asked me to sit beside him. He helped me to learn everything.”28 After Mackey was sold to Newark in midseason, Campanella became Baltimore’s starting catcher.

In the bottom of the first, Hughes singled with one out and scored on Wild Bill Wright’s double. Wright had finished 10th in the NNL2 in 1939 with a .365 batting average, and he scored next on Snow’s single.

Both pitchers notched scoreless second and third innings, but Baltimore added a run in the fourth and two more in the fifth. Through five innings, Manning had allowed 11 hits and a walk. Meanwhile, Hubert had shut down the Eagles. Stone launched his second home run of the series in the top of the sixth, but that was one of only two Newark hits in the game.

After six innings, the contest was called due to darkness. The Eagles had batted in all six frames; thus, the Elite Giants were named champions of the series, which gave them the opportunity to play for the Ruppert Trophy. Baltimore scored 29 runs in 31 innings in the four games. Although the Eagles had outhomered the Elite Giants, six to two, Baltimore’s team OPS of .843 bested Newark’s .795. Further, in the four games, the Elites had 44 hits, 10 more than their opponents, while each team drew 14 walks. The Newark pitching staff’s ERA was almost three runs higher than Baltimore’s.

Bill Byrd was one of Baltimore’s playoff stars. He won Game Three on the mound, putting Baltimore within a win of the series championship, and he also went 2-for-3 at the plate with a home run and two runs scored. For the series, Sammy Hughes banged out a team-high seven hits (in 15 at-bats), good for a .467 batting average and 1.329 OPS. For Newark, Biz Mackey was 6-for-12 and Mule Suttles went 4-for-15 (.267) with three home runs, three runs scored, and five runs batted in.

With the first-round series victory under their belts, the Elite Giants went on to face the Homestead Grays, winner of the other playoff series. It had taken the Grays five games to defeat the Stars; the first game was played at Municipal Field in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Games Two and Three consisted of a doubleheader on September 10 in Cleveland, and then the final pair of games were contested in Philadelphia (at 44th and Parkside). In a five-game championship series, Baltimore captured the pennant with three wins over the Grays (there was also a tie). According to the New York Times, in the finale, “the Baltimore nine registered a brace of runs in the seventh inning and earned a shut-out triumph, 2 to 0.”29

| Newark | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Baltimore | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | x | 5 | 11 | 2 |

WP: W. Hubert, LP: M. Manning

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org.

The author sincerely thanks Elizabeth Young Miller, social sciences librarian at the E.W. Fairchild-Martindale Library of Lehigh University, for her assistance with searching for sources.

In addition, I thank the team at the Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center of the Newark Public Library for scans of Newark newspapers.

Line scores found at https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/1939NNL1a.html. Accessed April 2023.

Notes

1 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 43.

2 Founded in 1930 as the Nashville Elite Giants, the franchise moved to Columbus, Ohio, in 1935 and then to Washington, DC, the following year, staying for just two seasons. The Elite Giants spent the next 11 years (1938-1948) in Baltimore.

3 The Eagles had been in Newark since 1936, after spending their inaugural season (1935) in the Negro National League as the Brooklyn Eagles.

4 “Elites, Grays to Vie for Ruppert Trophy, Sunday,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 23, 1939: 16.

5 Luke, 47.

6 Luke, 47.

7 James Overmyer, “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium: The House That Ruth Built and Satchel Furnished (with Fans),” an article in John Graf. ed., From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (Phoenix: SABR, 2021), found online at https://sabr.org/journal/article/black-baseball-at-yankee-stadium-the-house-that-ruth-built-and-satchel-furnished-with-fans/. Accessed April 2023.

8 “Black Yankees Bow, 4-0: Baltimore Giants Win Feature of Twin Bill at Stadium,” New York Times, July 3, 1939: 13.

9 “Negroes to Honor Stars: Baseball Pioneers to Be Guests at Doubleheader,” New York Times, July 2, 1939: S2.

10 The nominations for the Negro Baseball Hall of Fame came from Joe Louis, world heavyweight champion; Bill Robinson, veteran tap dancer; and Cab Calloway, orchestra leader. The nominees were Suttles, Wells, outfielder Fats Jenkins, pitcher Satchel Paige, catcher Josh Gibson, third baseman Little Black Francis, pitcher Cannonball Dick Redding, first baseman Oscar Charleston, pitcher José Mendez, center fielder Sam West, pitcher Bullet Rogan, and catcher Frank Duncan. See “Negroes to Honor Stars: Baseball Pioneers to Be Guests at Doubleheader.” Paige, Gibson, and Jenkins were the only players with multiple nominations.

11 Luke, 47.

12 It is difficult to reconcile this seeding with the won-lost records for each team. Using Baseball-Reference, Homestead won 36 games. Newark was second-best, with 32 wins. Philadelphia won 24 games, and Baltimore won 21 games. The author has not found evidence to support why Philadelphia and Baltimore were switched in the seedings. A possible explanation was to give the Elite Giants some weight for having won the second half, thus combining the old and new playoff systems.

13 Norm King, “August 6, 1939: Late Home Runs Lift West to Win in Negro League All-Star Game,” SABR Games Project, sabr.org/gamesproj/game/august-6-1939-the-east-west-all-star-game-got-their-vote/. Accessed April 2023.

14 Adams also played two games in 1939 as an outfielder. In eight games at the plate, he batted .417 (5-for-12, all singles).

15 “Homers Give Eagles Victory,” Newark Star Eagle, September 7, 1939: 16.

16 Stephen V. Rice, “Mule Suttles,” SABR Biography Project.

17 “Homers Give Eagles Victory.”

18 “Homers Give Eagles Victory.”

19 Byrd also made three total appearances for the Philadelphia Stars in 1943 and 1944.

20 In 1942 Byrd tied for the league lead in wins with Ray Brown of the Homestead Grays. In 1945 Byrd tied for the league lead in wins with Homestead’s Ray Welmaker.

21 Byrd appeared in seven East-West All-Star Games while pitching for Baltimore. In each of 1939 and 1946, Byrd played in two contests, while in 1941, 1944, and 1945, there was only one game.

22 Luke, 37.

23 To help them in the second half of the season, the Elites picked up five players from the Atlanta Black Crackers (first baseman James “Red” Moore, Tommy “Pee Wee” Butts, pitchers Ed Dixon and Felix Evans, and catcher Oscar Brown). The Black Crackers began the 1939 season playing in Indianapolis as the Indianapolis A.B.C.’s, but the team could not find a ballpark and broke up, allowing for the players to join Baltimore (see Luke). This meant that the Elite Giants had to make room for the new additions to the roster, so they sold Jim West to the Philadelphia Stars and Mackey to the Eagles.

24 For the regular season, Day had walked 25 batters in 87 innings pitched.

25 Retrosheet’s box score of the game leaves one column blank: the number of earned runs. Newspaper clippings do not list the number of earned/unearned runs in the game, so we cannot assess the impact of Newark’s errors.

26 “Newark Eagles Are Eliminated,” Newark Star Eagle, September 11, 1939: 14.

27 “Diamond Chips,” Newark Sunday Call, September 10, 1939: 22.

28 Luke, 34.

29 “Elite Giants Gain Title,” New York Times, September 25, 1939: 26.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Elite Giants vs. Newark Eagles

Ruppert Stadium

Newark, NJ

44th and Parkside

Philadelphia, PA

Oriole Park

Baltimore, MD

Box Scores + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.