1921 World Series Simulation: New York Giants vs. Chicago American Giants

Editor’s note: This story is a mock recap of a simulated 1921 World Series matchup between the all-white New York Giants of the National League and the Chicago American Giants of the Negro National League, conducted by SABR member Ted Knorr using the APBA baseball game. To learn more about baseball in 1921, visit the SABR Century Committee’s 1921 Century Project.

1921 New York Giants team photo (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

1921 New York Giants team photo (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

After the 1921 Negro National League season, Andrew “Rube” Foster’s Chicago American Giants, league champions for the second time in two campaigns, spent October on a barnstorming tour of the east, playing 18 games against Hilldale of Philadelphia and the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, both Eastern Black baseball powers and NNL associate members.

At the same time, John McGraw’s National League champion New York Giants were winning a hard-fought eight-game World Series over the New York Yankees, fresh off their first American League pennant in franchise history, in a series played entirely at New York’s Polo Grounds. Foster’s champions and McGraw’s champions passed within miles of each other that month, but in reality were separated by a much larger distance: baseball’s color line, which remained for 26 more years, until Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. In 1921 the paths of the American Giants and Giants never crossed.

But imagine if they had.

Our fantasy relies on an unlikely connection: Foster and Cap Anson, whose refusal to play against Black players four decades earlier established baseball’s color line. Years later, after a bitter separation from major-league baseball and facing financial decline, Anson’s semipro team played games against Foster’s Leland Giants, too late to alter his place in history as a prime mover of baseball’s most shameful legacy. But Anson and Foster had many conversations over the years about Negro Leaguers in the majors.

If? … When? … How good were they really? … How would your American Giants do in the Federal League? … Or the AL or NL?

Anson, as baseball’s first superstar, and Kenesaw Mountain Landis, as the commissioner, were very close. In fact, Landis, whose stature diminished as history recognized his role in maintaining a segregated game, leading to his name being stripped from the Most Valuable Player awards in 2020, delivered the eulogy at Anson’s funeral in April 1922. They had discussions even before Landis became commissioner about Black ballplayers and how they would fare in the majors.

After Landis’ first year as commissioner and after two years of successful operation of Foster’s Negro National League, these questions begat ideas in our fantasy version of 1921. Landis saw a potential fortune in matching up the New York Yankees, with their emerging superstar, young George Herman “Babe” Ruth, versus the St Louis Giants with their Black Babe, Black Ty, and Black Spoke all in one: Oscar Charleston.

The next step was to ensure everyone would get paid. Landis and Anson lined up Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and industrialist Henry Ford. Foster found trailblazing Black banker Jesse Binga and A’Lelia Walker, Madame C.J. Walker’s daughter.

In the end the impossible happened – but it ended up with both Ruth and Charleston in the grandstand. Still, John McGraw versus Rube Foster was “must see” in its own right.

It changed the National Pastime; it changed the country; it changed the world.

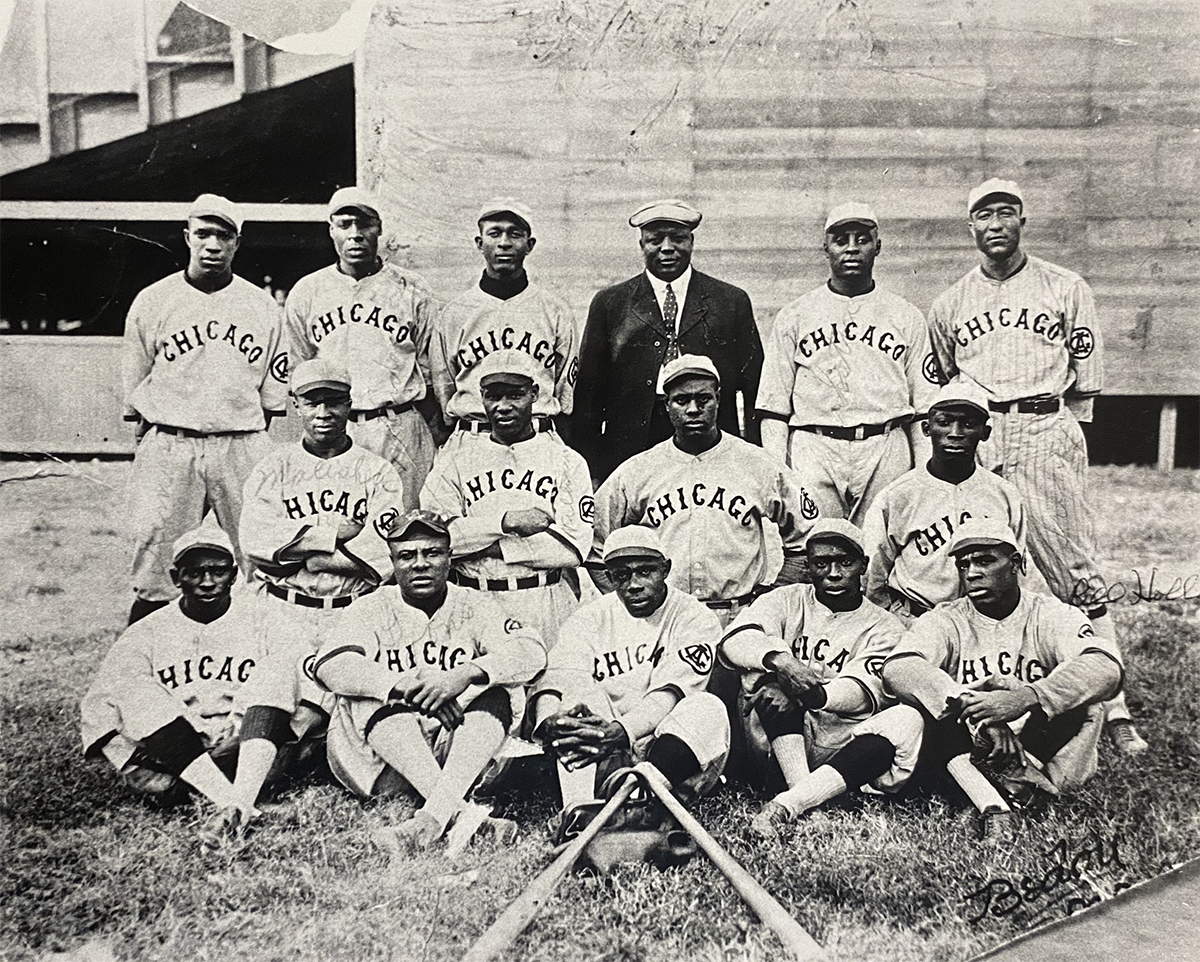

1919 Chicago American Giants team with manager Rube Foster in the top row in street clothes. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

The Chicago American Giants traveled to the Polo Grounds for Game 1 on October 19, six days after the New York Giants had clinched the World Series on the same field with a 1-0 win over the Yankees, and the Negro National League champions jumped ahead with four runs in the second inning. Going to the bottom of the eighth, Chicago had a 5-2 lead, and American Giants left-hander Dave Brown had limited McGraw’s team to four hits. But Brown tired, and the Giants – whose march to the 1921 National League pennant required some significant late-inning heroics – rallied with six straight hits, good for a 6-5 New York advantage. Giants swingman Jesse Barnes closed out the American Giants at the end, turning in two scoreless innings to earn the win.

A day later in Game 2, it was the American Giants’ turn for a late-inning rally. Backed by three-hit games by Ross Youngs, Johnny Rawlings, and Earl Smith, Art Nehf, whose 20 regular-season wins in 1921 included seven victories over the second-place Pittsburgh Pirates, nursed a 5-4 lead into the top of the ninth. But Bingo DeMoss led off with a walk, and Cristobal Torriente tripled him home with the tying run. Jim Brown’s double then drove in the Cuban great with the go-ahead run, evoking memories of late-game magic during the American Giants’ season. Dave Brown atoned for his performance in the late innings of Game 1 by coming out of the bullpen for two scoreless innings and being credited with the win.

The series moved to Chicago for Game 3 on October 22, the first of three games in three days at Schorling Park. Giants veteran right-hander Fred Toney was the story, winning the game with his bat and arm. With New York trailing 1-0 in the top of the third, Toney tied the game with a solo home run off Tom Johnson. Two innings later, his three-run homer erased another one-run American Giants lead and put the Giants ahead to stay. Toney battled through all nine innings, containing Chicago’s offense in New York’s 6-4 win.

Dave Brown returned to the mound for Game 4. He held the Giants hitless through four innings, until Frankie Frisch doubled. George Kelly followed with a deep drive over the fence in left. The home run gave New York a 2-0 lead, and those were all the runs Phil Douglas needed. In June 1921 Douglas – a much-traveled right-hander with a history of alcoholism and periodic disappearances – had left the Giants for four days after pitching all eight innings during a slugfest loss to the Phillies. Less than a year after this game, Landis banned Douglas based on evidence that he intended to defect to the St. Louis Cardinals. But here, Douglas turned in the most brilliant pitching performance of the series, allowing only one hit, Lyons’ fourth-inning single, and facing just three batters over the minimum. The Giants’ 4-0 win gave them a three games to one lead in the series.

The American Giants salvaged the third game at Schorling Park with a 4-3 win on October 24. Jelly Gardner’s single off Nehf drove in Jimmie Lyons with the tie-breaking run in the sixth; two innings later, the speedy Lyons raced home on George Dixon’s single for an insurance run. Chicago starter Tom Williams needed the extra breathing room; three ninth-inning singles brought in a run and Frisch hit a liner down the third-base line. But Dave Malarcher snagged it on a dive to end the game and secure the American Giants’ victory.

Back in New York for Game 6 on October 26, the Giants pounded out 20 hits against Johnson and Otis Starks. Youngs was the hitting star; his four hits formed a natural cycle, and he added three runs scored and three RBI. Frisch, Meusel, and Smith added three hits apiece, as the Giants moved one game from clinching the series with their 13-7 rout of the American Giants.

Douglas attempted to close out the American Giants at the Polo Grounds on October 27, but his Game 4 magic did not translate. Chicago rapped out four hits in the top of the first and had a 3-0 lead before New York had even batted. Dave Brown made his third start of the series for Foster’s team. When the Giants threatened to get back into the game with two straight singles to begin the second, Brown made his stand, setting down the next eight batters in a row and not allowing another hit until the ninth inning. By that time, the American Giants had their 6-1 Game 7 win in hand, cutting the deficit to four games to three as the series returned to Chicago.

Foster sent Tom Williams back to the mound on October 29 – with Dave Brown available on short rest for a winner-take-all Game 9 – but this time the Giants had the answers, rolling to a 6-0 lead by the fifth. Youngs scored the game’s first run in the second after singling and stealing, added to the lead with a third inning double, and chased home Frisch with a sacrifice fly in the fifth. For the series, the Texan hit .484 (15 for 31), with a homer, six runs scored and seven knocked in, earning the 1922 Ford Model T emblematic of the BCS MVP. Nehf – who had similarly won the World Series clincher after two earlier defeats – went the distance in New York’s 7-1 win.

McGraw’s men had taken the series over Foster’s team, five games to three. The games were no less competitive, thrilling, and magical than the World Series had been. They proved what anyone who had played in or witnessed interracial barnstorming games in those years already knew: that the best of Black baseball could hold their own against the class of the American and National Leagues.

JOHN FREDLAND is the director of SABR’s Games Project.

Click here to watch a SABR Century panel discussion about the simulated 1921 World Series with Sharon Hamilton, Phil S. Dixon, Ted Knorr, and John Odell: