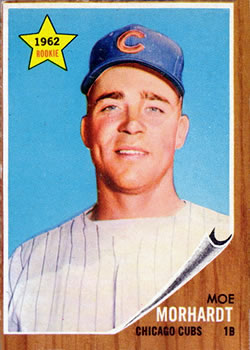

Moe Morhardt

In the spring of 1962, Meredith “Moe” Morhardt was in an enviable position. The left-handed hitting first baseman was starting his first full season with the Chicago Cubs and had been assured that he wasn’t going to be sent back to the minors. There was only one problem – he wasn’t playing.

In the spring of 1962, Meredith “Moe” Morhardt was in an enviable position. The left-handed hitting first baseman was starting his first full season with the Chicago Cubs and had been assured that he wasn’t going to be sent back to the minors. There was only one problem – he wasn’t playing.

By mid-May, Morhardt had appeared in just 18 games, all as a pinch-hitter. Going into that season, the Cubs had decided to move future Hall of Famer Ernie Banks from shortstop to first base. That left Morhardt as the odd man out. At age 25, he wasn’t ready to be a full-time pinch-hitter. So Morhardt did something drastic. He asked the Cubs to send him back to the minors.

“All I had on my mind was playing every day,” Morhardt said. “I just wanted to play. If I was anything, I was a sandlotter and a gym rat. That’s what I was. That’s the way I was my whole life.”1

The Cubs, who were in Philadelphia at the time, granted Morhardt his wish. “I flew to Chicago to pick up my wife and we started driving south,” Morhardt recalled. “Somewhere between Chicago and San Antonio, Banks got hurt. If I had been with the club . . . But I joined the San Antonio club, and I never went back to the big leagues.”2

While Morhardt stuck around in the Cubs’ farm system for three more years, his major-league career was over after just 25 games and 34 at-bats over the course of two seasons. That was only the first chapter of Morhardt’s baseball career, though, as he eventually returned to his home state of Connecticut and put together an impressive coaching career which saw him win three state championships at the high school level, along with coaching two college teams. Most importantly, Morhardt never second-guessed the decision he made that spring day in 1962, which ended his time at the top level. “I don’t have any regrets,” he said. “I just wanted to play more.”3

Meredith “Moe” Goodwin Morhardt was born in Manchester, Connecticut, on January 16, 1937. His first name came from his mother’s maiden name; he shared his middle name with his father, Frank G. Morhardt. The elder Morhardt helped found Cummins Diesel in nearby West Hartford. His wife, Jean, stayed home raising Moe and three younger siblings – brothers Jon and Jeffrey and sister Judith– in their 10-room house in East Hartford. One of Moe’s childhood memories was of standing at the window with his sister to watch President Franklin Roosevelt going past their house in a motorcade.4

Tragedy struck Moe and his family when he was seven. That was when Frank Morhardt died, at age 48, of a heart attack he suffered inside their house. Jean now found herself a single parent raising four children. She went to work as a telephone operator and the family had to move to a more modest house in the north end of Manchester. “My mother, she was something else,” Moe said.5

In Manchester, Morhardt started hanging out at Robinson Park, where the neighborhood children played pickup baseball games. “The first two years I played, I never hit,” Morhardt said. “They stuck me in right field.”6

When Morhardt was finally allowed to bat, he struggled to hit against the older kids. “I was 12 years old playing a sandlot game, and this kid said, ‘Morhardt, you stink. You can’t hit,’ ” recalled Morhardt, who never forgot the insult. Years later, Morhardt ran into the wife of his childhood insulter and told her, “I want to thank your husband for the greatest pep talk I ever got.”7

By the time he graduated from Manchester High School, no one was saying Morhardt couldn’t hit. He earned All-State honors in baseball during his junior and senior years, hitting over .450 both seasons, as well as starring during the summer for the Manchester American Legion team. Morhardt lettered for three years in soccer, basketball, and baseball, also earning All-State honors in basketball. A 6-foot-1 inch guard who never met a shot he didn’t like, he set the school scoring record in both his junior and senior years. “When you threw me the ball, it had no return address,” Morhardt said.8

Morhardt wanted to play football too. By his own admission, though, he weighed only 126 pounds when he entered high school, so his mother told him he couldn’t because he was too skinny. Instead, he played soccer, a sport he never had played before. Morhardt decided to play goalie because that was the only position that allowed touching the ball with hands.

After graduating from Manchester High in 1955, Morhardt went to the University of Connecticut on an athletic scholarship which covered his tuition. He played all three sports his freshman year but had to give up basketball after being placed on academic probation. At UConn, Morhardt was a team captain and an All-American in both baseball and soccer, leading UConn to its first two trips to the College World Series in 1957 and 1959.9

In 1957, UConn beat a Florida State team led by shortstop Dick Howser in the loser’s bracket of the College World Series, but then was eliminated by Iowa State. In 1958, only a 2-1 loss to Holy Cross in 10 innings in the championship game of the NCAA regionals kept UConn from returning to the College Series. There was no such suspense in 1959, when after losing to North Carolina in the third game of the season, UConn won 18 straight games to bring a 20-1 record to Omaha, Nebraska, for that year’s College Series. “Our senior year, that was a joke,” Morhardt said. “We had the best team in the country.”10 That success brought a lot of attention from major-league scouts, and they especially liked what they saw from Morhardt. “Ten to 15 scouts would come to games just because we were so good,” he said. “Twelve of the 16 teams contacted me.”11 The Chicago Cubs, whose New England scout was Lennie Merullo, got the inside track on signing Morhardt, though. They paid for his mother to travel to Omaha for the Series.12

Although UConn had the best record in the country, it dropped its opener to Penn State, 5-3, and then was eliminated by Western Michigan, 14-6. Morhardt went 1-for-10 in the two games. “We had two weeks off after the regular season and we just lost our edge,” he said. “In the Penn State game, I left seven guys on base.”

After the loss to Western Michigan, the Cubs whisked Morhardt and his mother to a hotel room, where they made a hard-sell pitch to sign him. It began at 12:30 P.M. and continued into the night. Charlie Grimm, the team’s vice president, told Morhardt to write down the number 50,000 on a pad of paper. “‘Think hard,’ he told me, ‘Because when I get your answer, I’m walking out that door and I won’t come back,’” recalled Morhardt. “The only thing I could think of was that I had been 1-for-10 in the College World Series, and I didn’t think any team would want me after that. So, I signed for a $50,000 bonus, pretty good money.”13

Adjusted for inflation, that $50,000 would be the equivalent of nearly $500,000 in 2022. The Cubs told Jean Morhardt that if Moe took their offer, she could buy a new house and a new car, “Here’s my mother. She’s got four kids and she’s working as a telephone operator,” Morhardt said. “I never saw 50 cents, let alone $50,000.”14

In retrospect, Morhardt regretted taking the first offer he got. When asked what he would have done differently about his career, he said, “I’d have listened to the other 11 teams that wanted to sign me at the time. I got a good deal from Chicago, and I took it, so you never know.”15

Morhardt, who had played the outfield at UConn, was an outfielder during his first year in the Cubs organization. After getting just nine at-bats with the Fort Worth (Texas) Cats of the Class AAA American Association, he was sent to the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Red Roses in the Class AA Eastern League to replace an injured player. He batted just .177 in Lancaster before being demoted to the Paris (Illinois) Lakers in the Class D Midwest League. He spent the rest of the season in Paris, batting .293 in 140 at-bats. Though his cumulative batting average at the three stops was an unimpressive .255, 25 of his 51 hits were for extra bases.

After the season, Morhardt returned to UConn, where he coached the freshman soccer team and finished up his course work, earning his physical education degree in February 1960.16

In 1960, the Cubs moved Morhardt to first base. He spent the entire season in Lancaster, rooming with future Cubs teammate Ken Hubbs, who died in a plane crash four years later at age 22. Morhardt struggled at the plate, batting only .205 with five home runs. “I didn’t exactly wear the ball out, but I learned a lot,” he said. “It was a pitcher’s league.”17

That was also the season where, in a game against the Binghamton (New York) Yankees, Morhardt witnessed what he called the strangest play he’d ever seen on a baseball field. “We were down a run in the last of the ninth, with a man on first base,” Morhardt told a reporter in 2012. “We used a slow running catcher, Terry Jones, as a pinch-hitter. He drove a ball deep to center field. Joe Pepitone got back on the ball. The ball struck the branch of a willow tree leaning over the fence. It deflected the ball, which hit Pepitone between the eyes. He dropped to the ground and by the time the right fielder, Bud Zipfel, got to the ball, Jones rounded the bases for a game-winning home run.”18

That offseason, on October 3, Morhardt married Georgie Cochrane, a nurse whom he had met in the summer of 1958 while he was playing in a summer college league in Nova Scotia. They met at a dance hall while Georgie was still in nursing school.19

The 1961 season got off to a memorable start for Morhardt, when after a spring training game in Mesa, Arizona, Hall of Famer Ty Cobb asked to meet some players. By that point, most of the Cubs veterans had hustled out of the clubhouse, so Morhardt and Hubbs were asked to come out and meet with Cobb, who died four months later.

Morhardt had his best professional season in 1961 playing for the Wenatchee (Washington) Chiefs of the Class B Northwest League. He batted .339 to edge Jesús Alou of the Eugene (Oregon) Emeralds for the batting title. He tied another future major leaguer, Dick Green of the Lewiston (Idaho) Broncs, for third in home runs with 18. Morhardt also was third in the league in RBIs (90) and had an OPS of 1.005.

As a reward, the Cubs called Morhardt up when the rosters expanded in September. Despite having five future Hall of Famers on the team (Banks, Billy Williams, Ron Santo, Lou Brock, and Richie Ashburn), the Cubs were heading toward a seventh-place finish, and their starting first baseman, Ed Bouchee, was having a poor season. The Cubs had started the season with seven potential first basemen and none of them had panned out.20 It was also the first season of the team’s two-year experiment with a College of Coaches, where 10 coaches rotated between the majors and the minors and four different coaches took turns managing the Cubs. The idea was the brainchild of team owner Philip Wrigley.21

Morhardt made his major debut on September 7 at Wrigley Field, going 0-for-2 with a walk against Pittsburgh’s Harvey Haddix in a 7-5 Cubs loss. It was a shaky debut in the field, as he committed two errors, including a throw to second base which sailed over Banks’ head and went into left field. The next day against Philadelphia, Morhardt got his first hit, an RBI single against Art Mahaffey, and he added a single off Chris Short later in the game. He also settled down at first base, where he had 20 total chances (18 putouts, two assists), just two short of the National League single-game record. The next day he made another error and went hitless against the Phillies.

The excitement of being in the big leagues was tempered, though, when Morhardt learned of his mother’s death and had to return home for two weeks. He returned to the Cubs in time to start four more games in the final week of the season, ending the year with singles in his final two at-bats against the Dodgers’ Stan Williams. In 18 at-bats, Morhardt had five hits (.278) and one RBI.

Although he was with the Cubs only for a short time that season, Morhardt wasn’t impressed with what he saw from a team which won just 64 games. “We were awful,” he said. “We played like a high school team. We just didn’t play baseball right.” Morhardt blamed the College of Coaches system for a lack of leadership and said the team’s star players didn’t take charge either. “Ernie (Banks) didn’t say anything. Billy (Williams) said nothing,” Morhardt said, noting that other respected veterans on the team, such as Ashburn and Don Cardwell, didn’t step up either.22

Morhardt followed through on his promise by having a good exhibition season. “Things were looking good for me,” he said. “I hit .368 in spring training and made the big club. But they had to find a place for Ernie – he was the institution – and it was first base.”24

With Banks playing first base every day, there was no spot in the lineup for Morhardt. The Cubs, meanwhile, were embarking on a historic season – in a negative sense. They lost 103 games, the first time over the century mark in franchise history, finishing six games behind the expansion Houston Colt 45s. Only the ineptitude of the other expansion team that year, the 120-loss New York Mets, kept the Cubs out of last place.

It also was the last season of the Cubs’ ill-fated College of Coaches. The Cubs did set a positive precedent that season by hiring former Negro League star and future Hall of Famer Buck O’Neil to join their coaching staff, making him the first Black coach in big-league history. As a Cubs scout, O’Neil had signed many of their players, including Brock. Yet the team failed to achieve an even greater milestone – O’Neil was not included in the College of Coaches, even though the front office had promised him he would be.25s.

“What a fabulous man he [O’Neil] was. He was even-tempered and always had a smile on his face,” Morhardt said. “He signed half of the team. The rumor was they didn’t let Buck coach third base because they didn’t think he was smart enough.”26

It wasn’t until 13 years later that a Black man, Frank Robinson, finally broke the managerial color barrier in the major

Morhardt did participate in two memorable games that season. The first was on Opening Day, April 10, when the Cubs played in the first major-league game ever played in Houston. Morhardt popped up against Bobby Shantz as a pinch-hitter in the fifth inning of an 11-2 loss, which set the tone for the Cubs’ season.

Exactly two weeks later, the Cubs were facing Sandy Koufax. The future Hall of Famer had already struck out 17 batters, one short of tying his own National League record.

With two outs in the ninth inning, Dodgers first baseman Tim Harkness lost a routine popup off the bat of Moe Thacker, allowing it to fall in fair territory a few feet away from him for a single.27 That extended the game, giving the left-handed Koufax another shot at the record-tying strikeout. A surprised Morhardt was then called upon to pinch-hit even though the Cubs had several right-handed batters available. “The coach who was running the team that day – I don’t want to give his name – didn’t like me,” Morhardt said. (The record shows that it was El Tappe.)

Koufax fell behind 2 and 0, but with the Cubs trailing, 10-3, Morhardt wasn’t going to swing at the next pitch. As it turned out, it was a hittable fastball right down the middle, bringing the count to 2-and-1. “There’s pitches you see the rest of your life,” Morhardt said. “And that’s the 2-0 pitch. I saw it all the way. Koufax then threw two more fastballs for strikes, getting Morhardt to look at a called third strike to end the game.28

Otherwise, it was an unmemorable five weeks for Morhardt, who pinch-hit in 18 of the Cubs’ first 34 games, going 2-for-16 with 2 RBIs. He started out 0-for-9 with six strikeouts before getting pinch hits in back-to-back games, including a two-run single off Don Larsen in the seventh inning of an 11-6 loss to San Francisco on May 4 for his only RBIs of the season. The next day, his seventh-inning single off Jim Duffalo ended up being his final major-league hit. That also ended up being a rare Cubs win as Morhardt ended up scoring the winning run on a single by Santo, which broke an 8-8 tie in a 12-8 victory. It was his only run scored of the season.

That was when Morhardt asked to be sent to the minors. “It’s hard to explain what you’re going through,” he said. “I just couldn’t sit there and pinch-hit.”29

Not only did Banks get hurt while Morhardt was driving to Texas, but once Morhardt got to San Antonio, he had to sit around in a hotel room for three days waiting for his new team to finish a road trip.30 Morhardt split the rest of the season between San Antonio and Wenatchee. He batted .275 in 80 minor-league games with six home runs.

Morhardt played two more seasons in the minors, putting together a solid season in 1963 at Wenatchee and a mediocre season in 1964 with a struggling Fort Worth Cats squad, which went 51-89 in the Texas League. He spent his offseasons as a substitute teacher, helping to support his growing family. Moe and Georgie’s three sons – Kyle, Darryl, and Greg – came along in rapid succession in 1960, 1961, and 1962, respectively. Daughter Wendy was born in 1968.

By the time Morhardt reported to another minor-league camp with the Cubs in 1965, it was clear that he was unlikely to make it back to the majors – and with Georgie taking care of their three sons, he needed to earn a better living. He told the Cubs he was retiring. He finished with a .206 average in 25 major-league games. He posted minor-league totals of 57 home runs in six seasons along with a .263 career average.

Morhardt then answered an ad placed by Boston Red Sox pitcher Earl Wilson, who needed someone to drive his car back from spring training in Arizona to Boston. In a way, it was a fitting end for Morhardt, whose first at-bat in professional ball had come against Wilson.

Wilson’s car, a Thunderbird convertible, broke down on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, delaying Morhardt’s return home. When he finally got to Boston, he drove to Fenway Park and told the attendant that the car belonged to Wilson. The attendant told Morhardt to wait; he soon came back with a $100 bill from Wilson.31

Morhardt returned to school, earning his master’s degree from Southern Connecticut State University. “My thesis was on pitching charts.” he said. “I fooled them enough that they let it go.”32

In 1967, Morhardt was hired as a physical education teacher and baseball and basketball coach at the Gilbert School in Winsted, Connecticut. During his 21 years as baseball coach, he compiled a record of 299-134, which included eight league titles and five appearances in the state championship game, three of which he won. The most notable of those was in 1979, when Morhardt’s three sons were in the starting lineup, and the team rallied from a 1-0 ninth-inning deficit to win 2-1 in 11 innings. “You look at them just like anybody else,” he said of coaching his sons.33

Morhardt, who was coaching baseball, basketball, and soccer, would have coached at Gilbert for longer. However, he resigned because he felt the administration didn’t back him up when he pulled the team out of the state tournament after he told the seniors not to participate in Senior Skip Day on a day when Gilbert had a baseball game, but they went ahead and skipped school anyway. “I would have coached at Gilbert until I retired,” said Morhardt, who taught for five more years after giving up his coaching positions.34

The next coaching stop for Morhardt was the University of Hartford, where, beginning in 1988, he spent five years as the batting coach and then two years as the head coach. The most notable player Morhardt worked with at Hartford was future Hall of Famer Jeff Bagwell. “You could tell he (Bagwell) was different,” Morhardt said.35

When he was voted into the Hall of Fame in 2017, Bagwell noted Morhardt’s influence on his career. “My college career was great,” Bagwell said. “We lived and died baseball every night. Moe Morhardt was wonderful as a hitting coach. He kept it very simple. He’s just a great baseball mind, in so many different ways. Every time I hear ‘Moe Morhardt,’ I smile.”36

After leaving Hartford following a disagreement with the athletic director, Morhardt spent three seasons as the head coach at Western Connecticut State University.37 He also coached the Danbury Westerners of the New England Collegiate Baseball League for six years.

Two of Morhardt’s sons played professional ball. Darryl played in the Atlanta Braves farm system; Greg, who as of 2022 was an area scout for the Boston Red Sox, played in the Minnesota Twins and Detroit Tigers chains. One of Greg’s teammates in the minor leagues was Jeff Trout, and Greg was credited with signing Jeff’s son, Mike Trout, while working as a scout for the California Angels. Darryl, as of 2022, was coaching three travel teams and father Moe was assisting with his U-17 team.38 Kyle was the vice president of an insurance firm, while Wendy was a stay-at-home mother. Morhardt also has seven grandchildren.

Morhardt, at age 85, said he still enjoyed working with teenage athletes. “I notice the kids aren’t much different,” he said.39

Looking back on his career, he was most proud of how in 1962 when the Cubs told him his spot on the major-league roster was guaranteed, he still went out and earned the spot in spring training. “That’s the thing I’m most satisfied with,” Morhardt said. “I didn’t want anything to be given to me.”40

Last revised: March 23, 2022

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Moe Morhardt for his input (telephone interview with David Bilmes, January 24, 2022).

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Howard Rosenberg and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Jean Morhardt’s maiden name and Frank Morhardt’s middle name came from geni.com.

Notes

1 Moe Morhardt, telephone interview with David Bilmes, January 24, 2022 (hereafter Morhardt-Bilmes interview).

2 Owen Canfield, “When it comes to baseball, Moe knows,” Hartford Courant, July 7, 1992, https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1992-07-07-0000114392-story.html (last accessed February 14, 2022).

3 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

4 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

5 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

6 Morhardt-Bilmes interview. Morhardt’s first nickname was “Lefty,” which he got when he first showed up for pickup games at Robinson Park. He got the nickname “Moe” when he was in middle school but couldn’t recall how it came about.

7 Steve Barlow, “Lot of lessons learned in 60 years of baseball,” Waterbury Republican American, October 10, 2021.

8 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

9 “Individual career history.” University of Connecticut Athletics. https://uconnhuskies.com/documents/2018/6/14/individual_career.pdf (last accessed February 18, 2022). The University of Connecticut athletic communications office was only able to provide partial statistics for Morhardt’s UConn career, crediting him with a .287 batting average his sophomore year and a .352 average his senior year. No statistics were available for his junior year.

10 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

11 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

12 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

13 Canfield, “When it comes to baseball, Moe knows.”

14 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

15 Andrew H. Martin, “Moe Morhardt interview.” The Baseball Historian. January 4, 2012. http://baseballhistorian.blogspot.com/2012/01/moe-morhardt-interview.html (last accessed February 15, 2022).

16 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

17 Morhardt-Bilmes interview. While rooming with Hubbs that year, Morhardt said that Hubbs was often reading pamphlets about how to become a pilot, which he eventually did. Hubbs was piloting the plane when he crashed to his death.

18 Martin, “Moe Morhardt interview.”

19 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

20 Canfield, “When it comes to baseball, Moe knows.” George Altman, Frank Thomas, and Dale Long were also first basemen who played for the Cubs that season. “By the end of the season, they were all gone,” Morhardt said.

21 Scott Ferkovich. “P.K. Wrigley and the College of Coaches.” The Hardball Times, June 2, 2015. https://tht.fangraphs.com/pk-wrigley-and-the-college-of-coaches/ (Last accessed February 17, 2022).

22 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

23 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

24 Canfield. “When it comes to baseball, Moe knows.”

25 Carrie Muskat, “Baseball icon O’Neil made history with the Cubs,” MLB.com. February 20, 2017. https://www.mlb.com/news/cubs-made-buck-o-neil-mlb-s-first-black-coach-c216445780 (Last accessed Feb. 20, 2022)

26 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

27 Gregory H. Wolf, “April 24, 1962: ‘Human Strikeout Machine’ Koufax strikes out 18 in the Windy City,” 2019. Society for American Baseball Research. https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-24-1962-human-strikeout-machine-sandy-koufax-strikes-out-18-in-the-windy-city/ (Last accessed February 19, 2022).

28 Morhardt-Bilmes interview. As a consolation, Morhardt noted that he owned a baseball card with Koufax’s autograph on it.

29 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

30 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

31 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

32 Barlow, “Lots of lessons learned in 60 years of baseball.”

33 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

34 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

35 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

36 David Borges, “Jeff Bagwell, headed to the Hall of Fame, proud of his Connecticut roots,” Middletown Press, July 21, 2017. https://www.middletownpress.com/mlb/article/Jeff-Bagwell-headed-to-Hall-of-Fame-proud-of-11752908.php (Last accessed February. 21, 2022).

37 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

38 Buster Olney, “Inside the discovery of Mike Trout,” ESPN.com. July 29, 2018. https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/24221790/mlb-discovery-mike-trout (Last accessed February 22, 2022).

39 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

40 Morhardt-Bilmes interview.

Full Name

Meredith Goodwin Morhardt

Born

January 16, 1937 at Manchester, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.