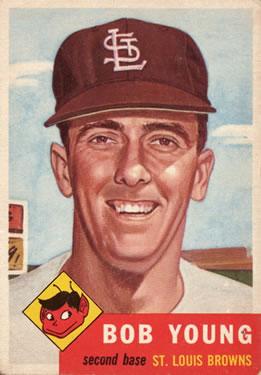

Bobby Young

Bobby Young grew up near Baltimore when the city had no major-league team. But like his grandfather, who remembered the Orioles’ championship clubs of the late 19th century, he longed for big-league baseball to return. When that did happen, Young became the first player to sign a contract with the modern-day Orioles.

Bobby Young grew up near Baltimore when the city had no major-league team. But like his grandfather, who remembered the Orioles’ championship clubs of the late 19th century, he longed for big-league baseball to return. When that did happen, Young became the first player to sign a contract with the modern-day Orioles.

His major-league career spanned all or parts of eight seasons (1948, 1951-1956, 1958), including four years as the primary second baseman for the St. Louis Browns/Baltimore Orioles franchise. When Baltimore returned to the American League after a 52-year absence in 1954, Young was the Orioles’ Opening Day leadoff hitter.

Robert George Young was born on January 22, 1925, in Granite, Maryland, an unincorporated community about 20 miles west of Baltimore. He was the only child of Joseph and Beatrice (Hamilton) Young. According to the 1930 census, his father was a foreman for Baltimore County and the family lived with Bobby’s maternal grandparents on Old Court Road. Young’s grandfather, Louis Hamilton, had been a teenager when the Orioles won three consecutive pennants (1894-1896) before major-league ball left the city following the 1902 season. He inspired Bobby’s dream of playing for the big-league Orioles should the majors return to the city one day.1

By 1940, Bobby’s parents had their own home on Florida Road.2 His mother had become a beautician. At Catonsville High School, Young made a name for himself as an athlete. In the fall of 1941, the Baltimore Sun reported that he scored six goals in one game for the soccer team.3 That winter, he scored a team-high 18 points for Catonsville in a 41-39 basketball win over McDonogh, including the tie-breaking basket with three seconds remaining.4

But baseball was his best sport. “Never forget the first time I saw Bobby,” said Catonsville coach Howard “Buck” Griffin. “It was on tryout day when we first started practicing for a new season. He was the last to report, the last to hit. He ambled up there, did everything wrong, the way he did right through his career, and hit nothing but line drives, just sort of sliced the ball to all fields.”5

Griffin, who had pitched briefly in the low minors, made Young a middle infielder and gave him pointers.6 “He was one of the truly great infielders I’ve ever coached,” Griffin recalled. “Was always the first one on that infield. He was a team man.”7 Young later named Griffin the person most responsible for his baseball career.8

The Baltimore Orioles had won their seventh straight championship of the Class AA International League (IL) the year that Young was born, but their next title wouldn’t arrive until 1944. Two years before that, Young tried out for the team at Oriole Park, but was told, “Go away until you get some size on you.”9

Following his 1942 graduation, Young enrolled at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland. After just one semester, he dropped out and joined the Marines. According to his World War II draft card, he stood 5-foot-11 and weighed 158 pounds (he was listed at 6-foot-1, 175 in the majors). He had a ruddy complexion and a scar on his chin.

Young spent part of his three-year enlistment playing for service teams at Marine Corps Air Station Eagle Mountain Lake, near Fort Worth, Texas.10 Following his discharge, he was recommended to Benny Borgmann, the St. Louis Cardinals scout, former minor-league infielder, and future Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Famer. At the time, Borgmann was coaching the Paterson Crescents of the American Basketball League. When the Crescents came to play the Baltimore Bullets, Borgmann followed up on the tip. “I saw Young just before the basketball game started and asked him to come to our dressing room between halves,” Borgmann said. “He did, and that’s where I signed him to his first contract in Organized Baseball.”11

In 1946, Young debuted in the Class B Interstate League with the Allentown (Pennsylvania) Cardinals. “We knew that Young had good legs, good big hands and was plenty fast,” recalled Borgmann, who managed St. Louis’s Triple-A affiliate that year.12 In 128 games, Young – a righty thrower who hit left-handed – batted .347 with 115 runs scored and a league-leading 16 triples to make the All-Star squad.13 That winter in the Panama Canal Zone League, he helped the Cristóbal Mottas win the championship.14

At some point during his first professional season, Young got married. He described himself as single when he filled out a questionnaire in May 1946, but the passenger log for the S.S. Panama, entering the Port of New York on April 10, 1947, indicated a change. The log included 19-year-old Phyllis M. Young, Minnesota-born, but married and residing at 3627 Florida Avenue in Baltimore.15 (That spring, a newspaper described her as a “native of Panama.”16) The 1950 census listed the couple at that address with two young sons, Robert Jr. and Joseph. A third, Dennis, was born in 1952.

In 1947, Young advanced to the IL –by then classified Triple-A – to play for the Rochester Red Wings. Before April was over, Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle observed, “He is a scat-cat on the basepaths, beating out bunts and stretching ordinary doubles into triples. Defensively, he has come up with two game-saving gems back of second.”17 As it happened, Rochester manager Cedric Durst shifted Young to third base for 43 games to make room for Nippy Jones.18 In 118 games overall, Young batted .315. He returned to Panama for winter ball that offseason.19

Back at Rochester in 1948, Young played his usual position full time. His batting average slipped to .268 in 126 games, but his .988 fielding percentage led IL second basemen.20 The Red Wings were heading to the playoffs, but the big-league Cardinals were trying to reach the postseason, too. With several of St. Louis’s regular infielders banged up. Young was summoned to the majors.21

He debuted on August 30 at Sportsman’s Park, as an eighth-inning pinch-runner at first for Babe Young after the Cardinals had loaded the bases. He advanced 90 feet on a two-run single by former Rochester teammate Jones that extended St. Louis’s lead to three runs, but he did not come around to score. In the ninth inning, Young remained in the game to man third base. He tagged George Shuba for the third out, ending the Brooklyn Dodgers’ game-winning, four-run rally.

When Bobby Young ran for Babe Young again one week later in Pittsburgh, he was erased on a line-drive double play. His only plate appearance came on September 21 in Boston, pinch-hitting against the Braves’ Johnny Sain in the seventh inning of the Cardinals’ 11-3 defeat. “I was real nervous,” Young acknowledged later.22 Sain, who earned his 22nd victory of the season that day for the NL pennant-winners, struck him out looking.

With future Hall of Famer Red Schoendienst entrenched at second base for the Cardinals, Young returned to Rochester in 1949 to form half of the Red Wings’ keystone combination with shortstop Dick Cole. Young lost his starting job in early June, however, after Rochester purchased shortstop Al Stringer from the New York Yankees’ organization and moved Cole to second base.23 After batting just .241 in 47 appearances, Young was traded to the St. Louis Browns on June 11 for third baseman Don Richmond.24 The Orioles had become the Browns’ Triple-A affiliate, so Young reported to his hometown team and raised his average to .268 in 128 overall IL games by season’s end.

In 1950, Young returned to Baltimore and hit .273 in 140 contests. He drew 62 walks – a personal best – and struck out just 23 times in 539 at-bats, but his most impressive statistical achievement came on defense. Young handled 329 consecutive chances without an error over a span of 60 games, breaking Jackie Robinson’s 1946 IL records of 301 and 55, respectively. (The streak ended on September 9 when umpire Larry Napp explained that he had called a runner safe the previous evening because Young’s foot missed second base on an attempted force play, resulting in a scoring change from an infield hit to an error.25) The Browns purchased Young’s contract on September 6.26 “I get good reports on Bob Young over in Baltimore,” explained Browns manager Zack Taylor.27

Young finished the season with Baltimore and helped them win the IL championship. The Orioles advanced to the Junior World Series but lost to the Columbus Red Birds of the American Association. The Baltimore Sun opined, “[Shortstop Eddie Pellagrini] and Bobby Young teamed up in the middle of the diamond to give the Stadium stalwarts one of the very best combinations they have had since the Joe Boley–Max Bishop era [1919-1923].”28 That winter, Young played for Almendares in the Cuban League.29

The Browns’ incumbent second baseman, Owen Friend, was inducted into the Army in December 1950 for two years of service during the Korean conflict.30 St. Louis still had former Yankees All-Star Snuffy Stirnweiss, but traded him to the Cleveland Indians late in spring training. On Opening Day 1951, the Browns lost 17-3 at Sportsman’s Park. It was a good day for Young, though, as he led off and collected his first three big-league hits – singles off Chicago White Sox southpaw Billy Pierce.

Young started a team-high 147 games in 1951 for the Browns, who had the majors’ worst record (52-102). He batted .260, led the club in runs scored (75) and triples (9), and paced AL second baseman by participating in 118 double plays. “He’s been a splendid glove man all season. More to the point, in the long range plans of the Browns, Young rates high,” noted the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in August. “[Team] President Bill Veeck has praised Young’s fine competitive spirit, his fielding ability, and his penchant for finding devious ways to get on base.”31

The following spring, Veeck dispelled rumors that the Browns were interested in trading for former two-time All Star Cass Michaels. “I think we have two second basemen better than Michaels, Bobby Young and Mike Goliat,” Veeck insisted. “As a matter of fact, I just got through talking to [new Browns manager] Rogers Hornsby and he is really high on Young.”32

Hornsby had previous experience as player/manager while he was still building his playing credentials for his 1942 induction into Cooperstown. But in his first stint as a non-playing big-league skipper in 1952, he was replaced before mid-June upon proving too unpopular with his players. For example, when Young sought permission to visit his bedridden wife during her difficult pregnancy, Hornsby refused. In Beerball, his history of St. Louis baseball, Ed Gaus reported, “Young grabbed a bat and waited to ambush Hornsby, but he was intercepted by the team’s traveling secretary.”33

Young led AL second baseman in twin killings for the second straight year and batted .247 with his major-league best of 39 RBIs in a Browns-high 149 games. Two highlights of his ’52 campaign involved future Hall of Famer Bob Feller. On April 23, Young tripled to lead off the bottom of the first inning against the Cleveland Indians’ right-hander. Young then scored on an infield error – the only tally in a 1-0 Browns victory in which Feller and St. Louis southpaw Bob Cain permitted just one hit apiece. In Cleveland on August 13, Young’s tiebreaking three-run homer off Feller with two outs in the top of the sixth proved decisive in another Browns triumph. Led by manager/shortstop Marty Marion, St. Louis moved up one notch, to seventh place, with a 64-90-1 record.

Veeck attempted to relocate the Browns to Baltimore for the 1953 season. But on March 16 – less than a month before Opening Day – the other AL owners blocked him by a 5-2 vote.34 “It was tough to play in St. Louis after Bill Veeck’s plan to move to Baltimore first backfired,” Young recalled a year later. “The crowds that did show up heckled us.”35

The Browns were at Comiskey Park for the White Sox’s home opener. With two outs in the top of the seventh, Young doubled to right-center – St. Louis’s only hit in a 1-0 defeat to Chicago’s Pierce. (The victorious White Sox managed only two hits – both singles.) Considering it was the second time in less than a year that Young alone prevented an opposing hurler from no-hitting St. Louis, one reporter wrote, “It’s about time the pitchers union started boycotting Bobby Young.”36

Young, nicknamed “The Razor” because of his lean physique, hit .255 in 148 games with 22 doubles, his big-league best. He just missed leading the circuit’s second basemen in double plays for a third straight year, turning one fewer than New York’s Billy Martin. Two days after the Browns ended their season in last place with a 54-100 record – including just 23-54 at home – AL owners voted unanimously to approve the franchise’s move to Baltimore under new ownership.37

No Browns player was happier about the team’s new home than Young, who had continued to make his offseason home near Baltimore. That winter, the Washington Post reported that he had even volunteered to sell tickets.38 First, Young joined a barnstorming tour of the South with an all-star squad organized by Jackie Robinson. In Birmingham, Alabama, however, Young, Gil Hodges, and Ralph Branca were not allowed to suit up for a game against the Indianapolis Clowns because of a local ordinance banning blacks and whites from playing together.39

On the day before he turned 29, Young became the first player to sign a major-league contract with a Baltimore-based team in 52 years. “It’s a wonderful birthday present, and I’m tickled to death to be the first to sign,” he said.40

Young led off for the Orioles on Opening Day in Detroit and went 0-for-3 in a shutout defeat. The next day, he doubled to start the contest against the Tigers’ Ray Herbert and scored the modern Orioles’ first run on Sam Mele’s bases-loaded single. When Young doubled again in Baltimore’s home opener, it was the first-ever two-base hit in a major-league game at Memorial Stadium.

Overall, Young batted .245 with four homers in 130 games while displaying his usual steady glove. “He was outstanding defensively, especially turning the double play,” recalled Billy Hunter, the Orioles’ shortstop and Young’s roommate in ’54. “He almost always threw the relay to first the same way, with a sweeping arm motion from about waist high. If you were the baserunner, you’d better slide someplace else, because that’s where the ball would be coming.”41

The Orioles finished ahead of the Philadelphia Athletics but lost 100 games. On September 9, Young was involved in a memorable, yet disappointing, play. Baltimore righty Joe Coleman had a no-hitter going against the Yankees when New York’s Enos Slaughter grounded a ball toward Young to start the top of the eighth inning. But, as described by Hunter, “A made to order two-hopper hit something and bounced over Bobby Young’s head.”42 Despite Young’s effort to convince the official scorer to charge him with an error, Coleman wound up with a one-hitter and a 1-0 victory.43

“I busted my butt to get it, but the ball kicked up and ticked off my glove,” Young recalled 25 years later. “I knew I had made a mistake but, when I went into the clubhouse, Coleman told the sportswriters, ‘The man did everything he could. What more could you expect?’ I’ll never forget Joe for that.”44

Young went back to the Cuban League that winter but returned to the U.S. early after tearing cartilage in his right rib cage.45 Then, during spring training 1955, he fouled a ball off his left foot during batting practice on March 18 and fractured a bone in one of his toes. “The Doc told me I’d be out for two or three weeks,” Young lamented. “I can’t wait that long. If I do, somebody else will have my job before I get started again. Too many good looking ball players around here.”46

As it happened, Don Leppert started Baltimore’s first two games at second base in 1955, but Young was back in the lineup for the Orioles’ third contest, on April 16. Young started 54 of the first 69 games under new Baltimore manager Paul Richards. His batting average was just .199, however. In a waiver deal on June 27, Young was traded to Cleveland for 38-year-old infielder Hank Majeski.47

With Cleveland, Young appeared in 16 games (nine starts) before he was waived again to make room for veteran pitcher Sal Maglie on July 31. No team claimed Young, but Indians GM Hank Greenberg realized that he still had options remaining and invited him to go to the minors with the promise of a big-league call-up in September.48 Young reported to the Indianapolis Indians and hit .366 in 34 games in the Triple-A American Association. He went 2-for-6 in two September appearances for Cleveland and finished 1955 with a .221 average in 77 major-league games.

That winter, Young flew to Germany with Cincinnati Redlegs manager Birdie Tebbetts, former White Sox pitcher Joe Haynes, and others to conduct clinics for Army Air Force personnel. He had been recommended by Orioles business manager Herb Armstrong. “It’s quite an honor for me,” Young said.49

Young opened 1956 with Cleveland but he appeared in just one game as a pinch-runner before he was sent down to Indianapolis. He remained there for the rest of the season and hit .330 in 97 games. After winning the American Association championship, Indianapolis swept Rochester to claim the Junior World Series. In the fourth and final game, Young’s two-run homer helped Indianapolis triumph, 6-0.50

In 1957, Young began the season in the open classification Pacific Coast League with the San Diego Padres, a Cleveland affiliate. He hit .247 in 25 games before he was sold to the Philadelphia Phillies organization on May 8.51 Young returned to the IL to play for the Miami Marlins. “They went out and got the big double play man, Bobby Young,” remarked Rochester first-base coach Mo Mozzali. “He doesn’t hit much, but he’s got the glove… He’s just about the smoothest in the minors. He doesn’t have to hit much.”52 In 105 games, Young batted .245 with seven homers, his professional high.

Young began 1958 with Miami by hitting .253 in 59 games. On June 21, he made it back to the majors when the Phillies purchased his contract.53 Solly Hemus and Ted Kazanski were Philadelphia’s primary second basemen, so Young started just 12 of what proved to be his last 32 appearances in the big leagues. In 60 at-bats, he hit .233. He completed his career with a .249 average, 15 homers and a .980 fielding percentage in 687 games.

After baseball, Young returned home to Rockdale, Maryland, and operated a janitorial business.54 In the mid-1970s, he became a construction engineering consultant.55 At some point, Young and his wife divorced.56

Between games of a doubleheader at Memorial Stadium on July 21, 1964, Young participated in a re-enactment of the modern Orioles’ first home opener. As he had done in the historic contest 10 years before, he doubled off right-hander Virgil Trucks.57 In 1974, Young was one of eight 1954 Orioles players to appear for another commemorative ceremony.58 He remained a loyal Orioles supporter and attended games when he could.59

On January 25, 1985 – three days after his 60th birthday – Young had a heart attack. He was still a patient at Baltimore County General Hospital on February 4 when he suffered a second heart attack, which proved fatal.60 As of 2022, his burial details remained private.

“He loved playing for Baltimore,” Young’s son Dennis recalled shortly after his father’s death. “He was a local talent and he took a lot of pride in that. The thing I know best about him is how much he loved the people of this town and the city itself. He was happy to be a part of it.”61

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and https://sabr.org/bioproject.

Notes

1 “Home-Towner Bobby Young Realizing Life’s Ambition,” Washington Post, March 1, 1954: 11.

2 Although Florida Road is the name recorded by the census, Young wrote Florida Avenue on his World War II draft card, and his wife used “Avenue” instead of road for the address on a 1947 passenger log for her trip home from winter baseball in Panama.

3 “Catonsville Booters Defeat Sparks, 10-0,” Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1941: 13.

4 “Catonsville Rallies to Beat McDonough Five,” Baltimore Sun, February 18, 1942: 16.

5 Bob Maisel, “Bobby Young: A Special Guy on ’54 Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, February 10, 1985: 1B.

6 “Howard F. Griffin Bio,” https://www.washingtoncollegesports.com/insideAthletics/hof/bios/griffin_howard (last accessed September 4, 2022).

7 “Bobby Young, the First to Sign with Orioles in ’54, Dies at 60,” Baltimore Sun, February 6, 1985: 5D.

8 Bobby Young, American Baseball Bureau publicity questionnaire, May 8, 1946.

9 “Home-Towner Bobby Young Realizing Life’s Ambition.”

10 “Bobby Young, the First to Sign with Orioles in ’54, Dies at 60.”

11 Borgmann added, “[Fort Worth resident] Ed Konetchy, the old major leaguer, had told [Cardinals scout] Joe Mathes about this boy Young, and Mathes asked me to talk to him when I got to Baltimore.” “Inside Stuff,” Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), April 21, 1953: 38.

12 “Inside Stuff.”

13 “Redbirds’ Bob Young and Burgett Picked on Inter-State All-Stars,” Morning Call, September 5, 1946: 16.

14 “Cristobal Leads in Canal Zone,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1947: 21.

15 New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1957 (accessed through ancestry.com).

16 Elliot Cushing, “Sports Eye View,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), April 20, 1947: 53.

17 Elliot Cushing, “Sports Eye View,” Democrat and Chronicle, April 22, 1947: 20.

18 Elliot Cushing, “Sports Eye View,” Democrat and Chronicle, August 21, 1947: 26.

19 Leo J. Eberenz, “Cerveceria Seeks Sommers,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1948: 19.

20 “Meet the New Browns,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 6, 1951: 1C.

21 George Beahon, “Young Goes to Bolster Hurt Cards,” Democrat and Chronicle, August 30, 1948: 26.

22 Edwin H. Brandt, “Bobby Young Realizes Life’s Dream,” Baltimore Sun, January 19, 1954: 15.

23 George Beahon, “Red Wings Trade Bobby Young for Birds’ Richmond,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 12, 1949: 3D.

24 Beahon, “Red Wings’ Trade Bobby Young for Birds’ Richmond.”

25 Associated Press, “Errorless Play at End,” New York Times, September 10, 1950: 148.

26 The Browns acquired Brown and southpaw Irv Medlinger for a reduced price by allowing to Orioles to keep righty Joe Payne, who was with Baltimore on option. Associated Press, “Browns Obtain Two Orioles in Trade,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 7, 1950: 1C.

27 Robert L. Burnes, “The Bench-Warmer,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 12, 1950: 1C.

28 C.M. Gibbs, “Phillies Buy Ed Pellagrini,” Baltimore Sun, September 29, 1950: 17.

29 Pedro Galiana, “Bilko Puts on One-Man Show in Tying Cuban League’s RBI Record,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1950: 51.

30 “Browns’ Friend, Kokos in Camp–Fort Houston,” Washington Post, December 15, 1950: B9.

31 Robert L. Burnes, “The Bench-Warmer,” St Louis Globe -Democrat, August 16, 1951: 1C.

32 “DeWitt ‘Shopping’ in Florida, Visits’ Senators’ Camp,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 4, 1952: 1C.

33 Ed Gaus, Beerball: A History of St. Louis Baseball, (Bloomington Indiana: iUniverse, Inc., 2001): 138.

34 “Louis Effrat,” Transfer of Browns to Baltimore Rejected by American League Club Owners,” New York Times, March 17, 1953: 32.

35 “Home-Towner Bobby Young Realizing Life’s Ambition.”

36 Associated Press, “Bobby Young Again Spoils No-Hit Bid,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, April 17, 1953: 17.

37 Jesse A. Linthicum, “Big League Ball Back in City as Browns Deal is Approved,” Baltimore Sun, September 30, 1953: 1.

38 “Home-Towner Bobby Young Realizing Life’s Ambition.”

39 Red Smith, “Views of Sports,” Democrat and Chronicle, October 25, 1953: 52.

40 James C. Elliot, “Bobby Young First to Sign 1954 Oriole Contract,” Baltimore Sun, January 22, 1954: 17.

41 Maisel, “Bobby Young: A Special Guy on ’54 Orioles.”

42 Lou Hatter, “Motley ’54 Birds Had Fun, Climbed from Cellar,” Baltimore Sun, April 1, 1979: C1.

43 Maisel, “Bobby Young: A Special Guy on ’54 Orioles.”

44 Hatter, “Motley ’54 Birds Had Fun, Climbed from Cellar.”

45 Lou Hatter, “Bobby Young Becomes 7th Oriole to Sign Contract,” Baltimore Sun, January 9, 1955: S1D.

46 Lou Hatter, “Casualties,” Baltimore Sun, March 20, 1955: 39.

47 Associated Press, “Young Sent to Cleveland on Waivers,” Washington Post, June 28, 1955: 28.

48 Lou Hatter, “Young,” Baltimore Sun, August 4, 1955: 15.

49 “Bobby Young to Help with Clinic in Germany,” Baltimore Sun, January 26, 1956: S20.

50 Associated Press, “Red Wings Lose Fourth Straight,” Baltimore Sun, October 1, 1956: 19.

51 George Beahon, “Dugout Diggin’s,” Democrat and Chronicle, May 9. 1957: 47.

52 Paul Pinckney, “In the Pink…,” Democrat and Chronicle, May 19, 1957: 17.

53 Associated Press, “Bobby Young Bought from Miami by Phils,” Baltimore Sun, June 22, 1958: 1D.

54 “Bobby Young, the First to Sign with Orioles in ’54, Dies at 60.”

55 Hatter, “Motley ’54 Birds Had Fun, Climbed from Cellar.”

56 The 1978 wedding announcement for Young’s youngest son identifies Dennis’s mother as “Mrs. James Hamilton. “Weddings,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1978: E13.

57 Jim Elliot, “Crowd Enjoys Shrine Night,” Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1964: 17.

58 Bob Maisel, “Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, April 8, 1974: C3.

59 “Bobby Young, the First to Sign with Orioles in ’54, Dies at 60.”

60 “Bobby Young, the First to Sign with Orioles in ’54, Dies at 60.”

61 “Bobby Young, the First to Sign with Orioles in ’54, Dies at 60.”

Full Name

Robert George Young

Born

January 22, 1925 at Granite, MD (USA)

Died

January 28, 1985 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.