At the start of the 1921 season, the New York Yankees were a team with a long history of losing. When co-owner Frank Farrell proposed that the New York Giants meet his team in a postseason championship back in 1904, the Giants rejected the idea outright, characterizing the overture as an “absurd challenge [from] a lot of nobodies.”

By the end of 1921 the “nobodies” had become serious World Series contenders. Before the decade was over, the Yankees had become one of the greatest baseball teams of all time. What happened?

By the end of 1921 the “nobodies” had become serious World Series contenders. Before the decade was over, the Yankees had become one of the greatest baseball teams of all time. What happened?

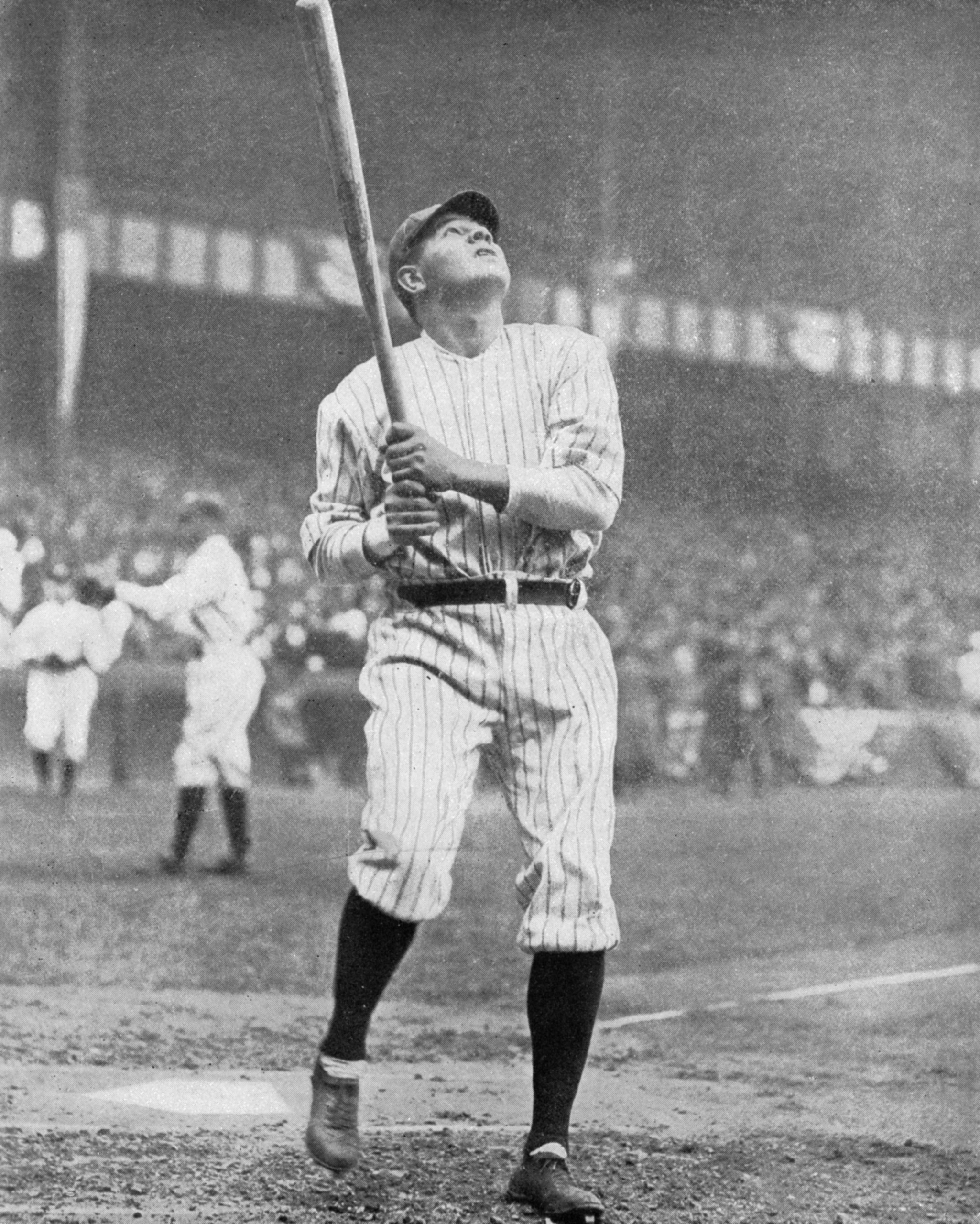

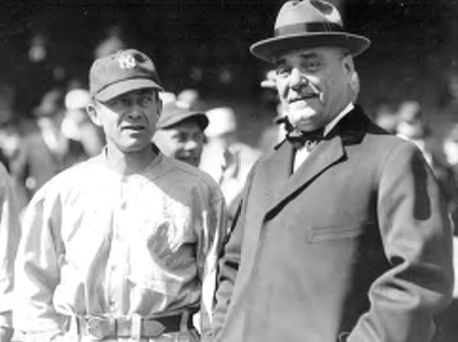

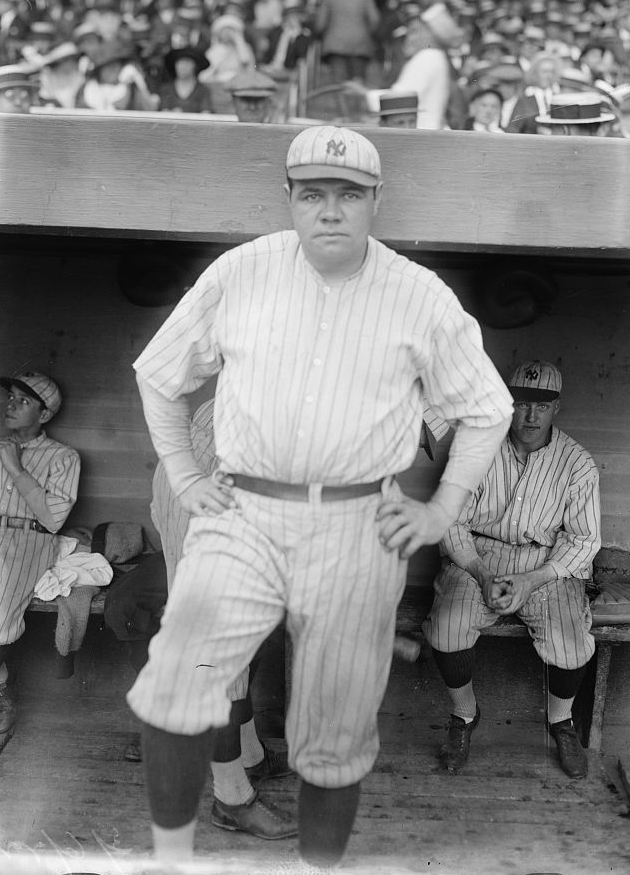

A number of factors combined to make possible the Yankees’ surprising climb from the American League basement to baseball mastery. The Yankees’ wealthy owners, Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, could afford to tempt other owners to relinquish star players. The team also had the good fortune to have Miller Huggins as a manager, and to bring on the shrewd Ed Barrow in fall 1920 to serve as the team’s general manager. Above all, they had Babe Ruth.

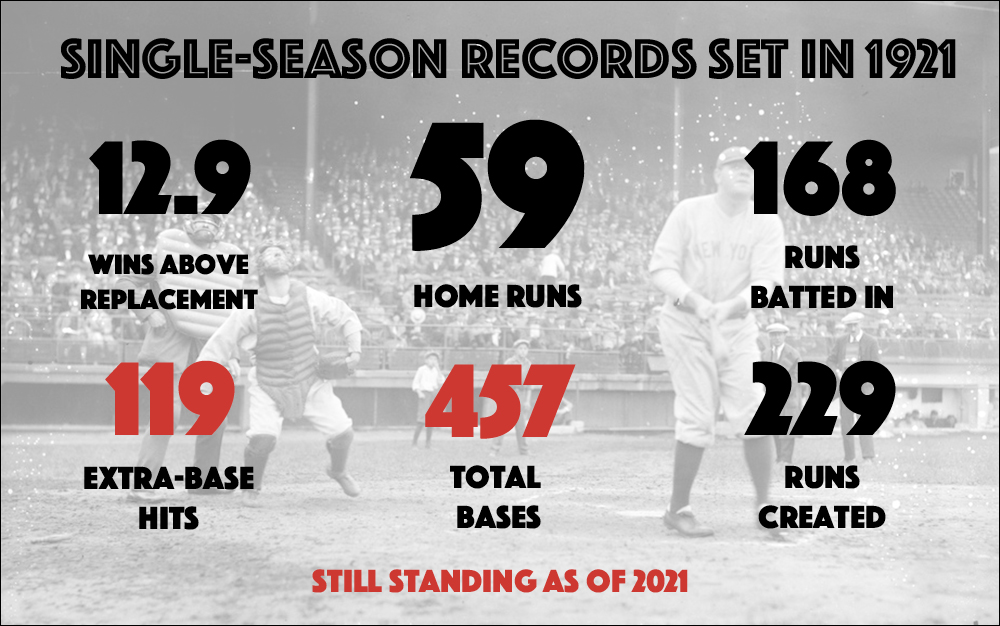

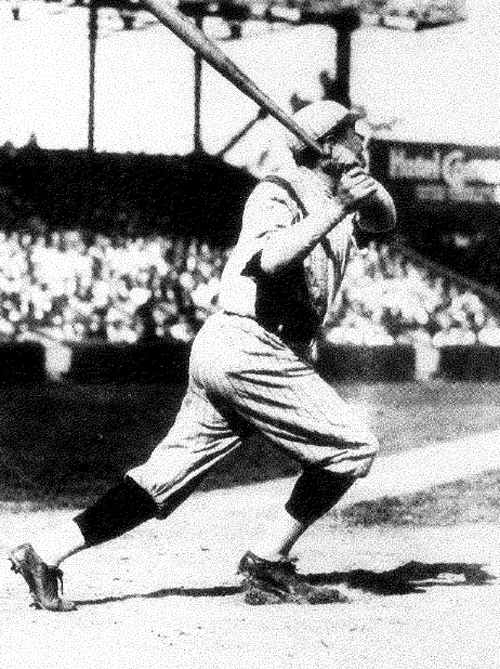

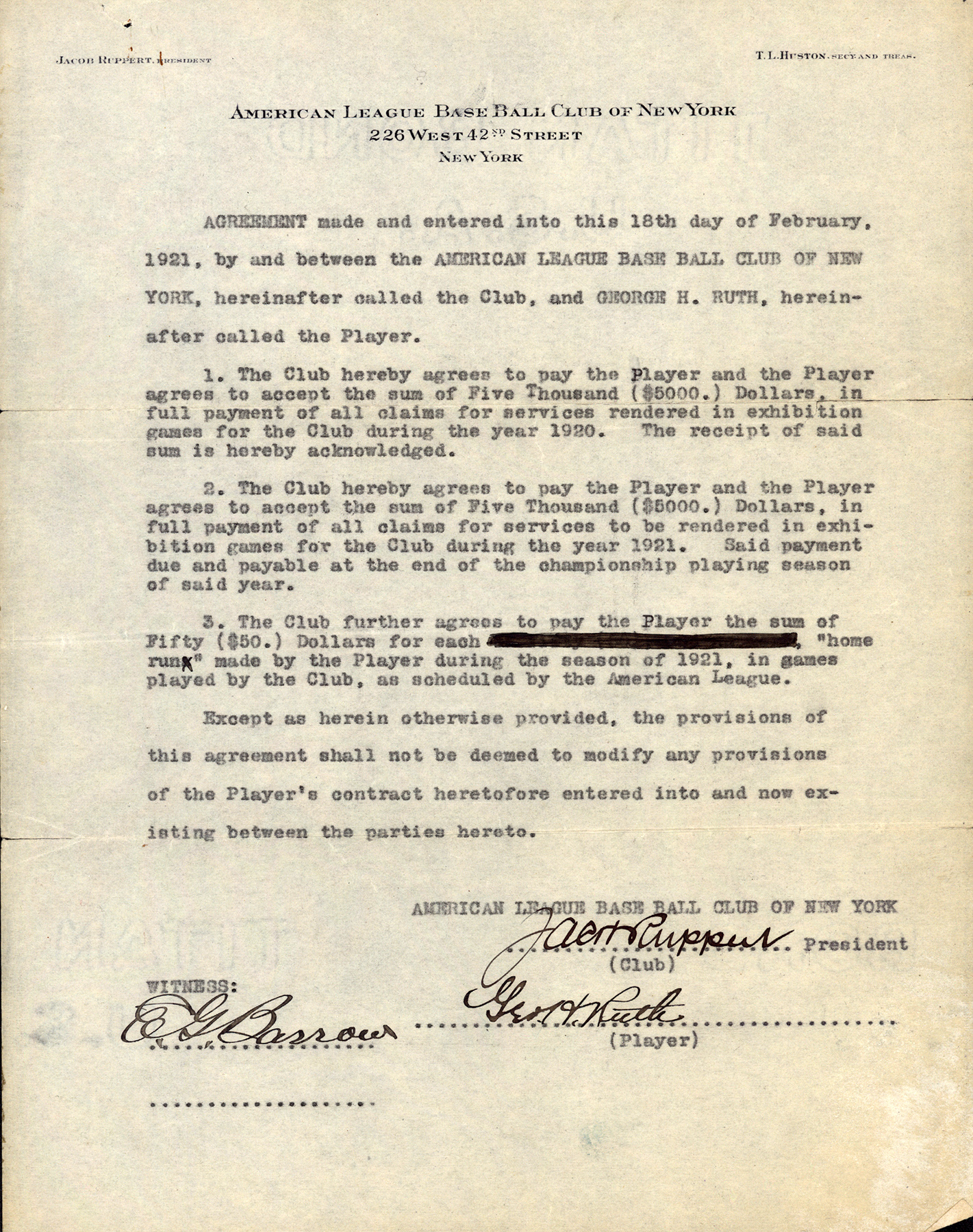

As Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg wrote in their award-winning book, 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York, the Bambino was the force “behind the Yankees’ rise in the standings and at the box office. In 1920, Ruth’s first year in New York, the Yankees outdrew the Giants — the team that owned and shared their ballpark, the Polo Grounds — by 360,000 fans,” becoming the first major-league team to top 1 million fans in home attendance. In 1921, when Ruth hit 59 home runs to break his own record set the year before, his contract offered him a $50 bonus for each home run, a mistake the Yankees’ owners never made again.

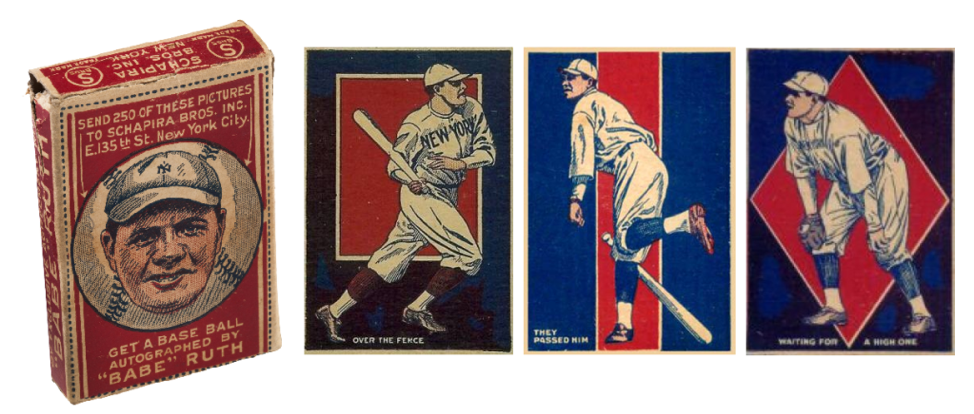

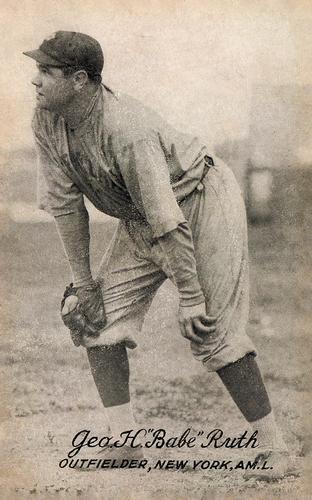

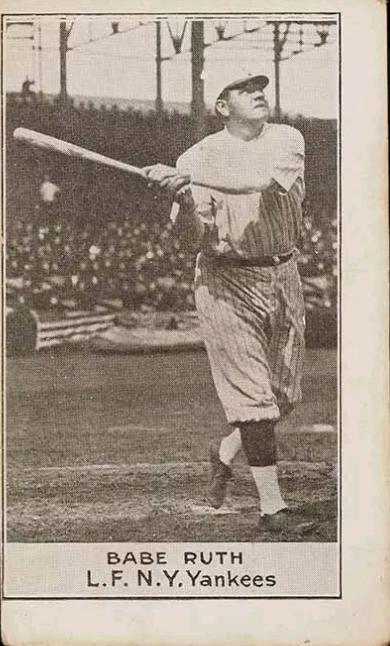

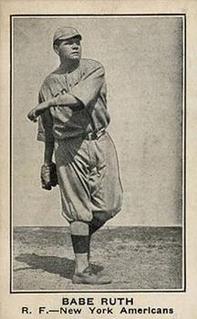

Ruth’s extraordinary baseball talent coincided with the beginnings of modern-day celebrity culture. Exposure via early film and radio along with magazines and newspapers made Ruth an American icon. Even in baseball cards, Ruth upset previous norms by becoming in 1920 the first baseball player to be featured in single-player baseball card sets. In 1921, kids buying a single-player baseball card set depicting Ruth needed to accumulate 250 boxes to earn “a baseball signed by Babe Ruth.”

— Sharon Hamilton

- Read more: “The 1921 New York Yankees,” by Alan Raylesberg

- Read more: “Baseball Cards of 1921,” by Jason Schwartz