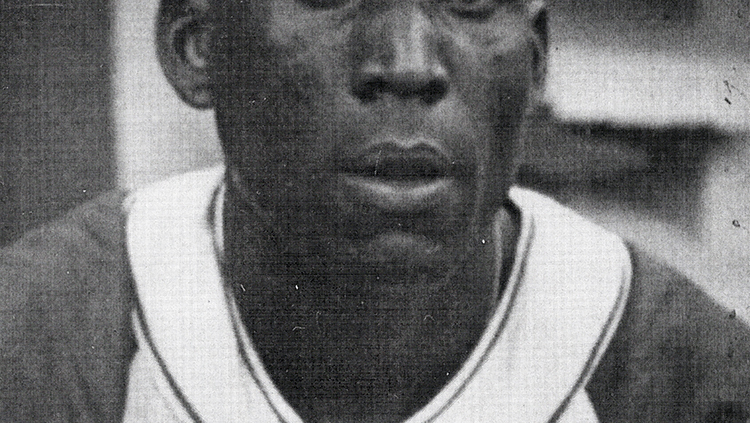

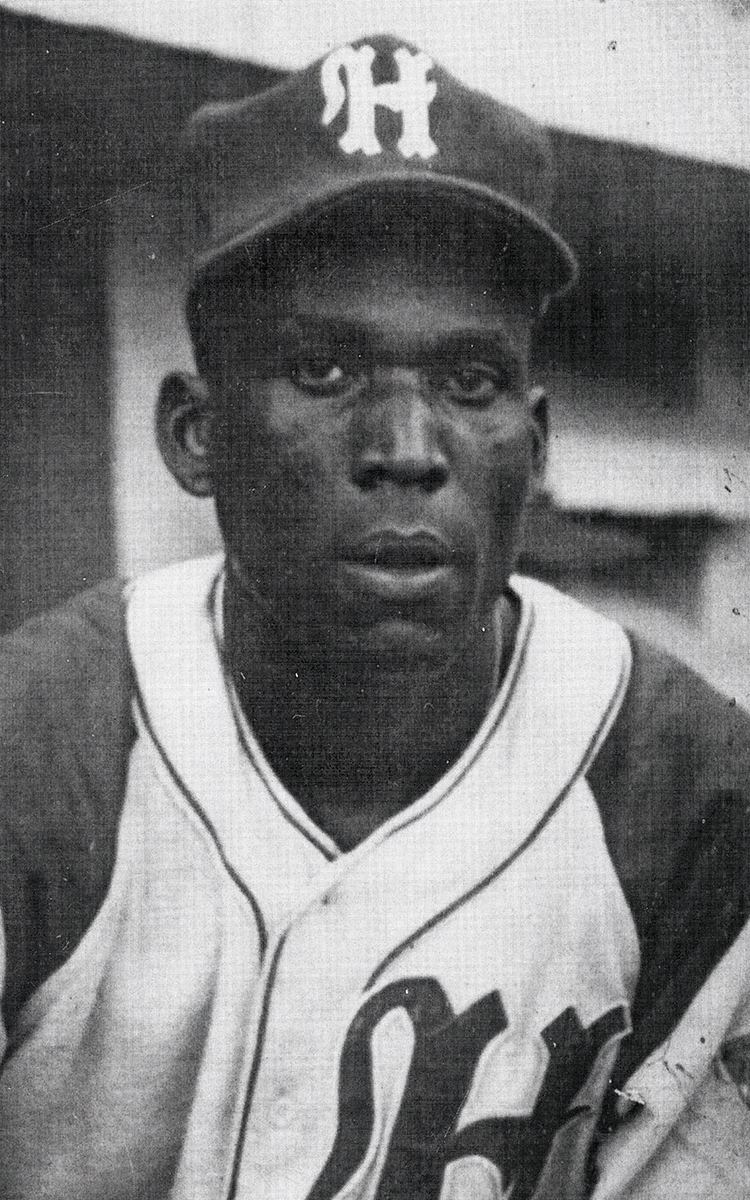

Marvin Williams

On April 16, 1945, after fierce lobbying by Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith,1 the Boston Red Sox held a tryout at Fenway Park for three African American players: Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and 25-year-old Marvin Williams.2 The trio took infield practice and hit against Red Sox pitchers, but not one player was signed. Manager Joe Cronin told them they could play, but he was skeptical that any owner would put a black player on his team.3 “If one (African American) is signed and don’t make it, you’ll hurt the rest of ’em,” Williams recalled Cronin telling them that day.4

On April 16, 1945, after fierce lobbying by Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith,1 the Boston Red Sox held a tryout at Fenway Park for three African American players: Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and 25-year-old Marvin Williams.2 The trio took infield practice and hit against Red Sox pitchers, but not one player was signed. Manager Joe Cronin told them they could play, but he was skeptical that any owner would put a black player on his team.3 “If one (African American) is signed and don’t make it, you’ll hurt the rest of ’em,” Williams recalled Cronin telling them that day.4

There has been speculation that the tryout was a sham because the team’s best players were heading out on a road trip and were not around to participate or provide input.5 The reluctance of the Red Sox to sign Black players in 1945 is supported by the fact that the Red Sox were the last major-league team to integrate, which they did in 1959, when Elijah “Pumpsie” Green became the first Black player in franchise history. However, Williams maintained that the tryout was genuine. The three players were supposed to work out for the Boston Braves as well, but many years later Williams recalled, possibly erroneously, that the Braves tryout was cancelled following the death of President Franklin Roosevelt on April 12.6

Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier two years after Williams’ tryout. Sam Jethroe won the National League Rookie of the Year Award in 1950 playing, ironically, for the Boston Braves, and led the league in steals in 1950 and 1951.7 Marvin Williams, “for some unexplainable reason,”8 was never given the opportunity to play in the American or National League.

Williams played for 57 teams in and out of Organized Baseball in five countries over nearly 20 years,9 and became one of the first African American managers of an integrated team. Based on his record in the Negro Leagues, the Caribbean, and the minor leagues, it is clear that Williams was a player of major-league quality who was forced to be a baseball vagabond due to the color of his skin.10

Marvin Williams was born on February 12, 1920, in Haslam, Texas.11 His parents were named Frank and Eva.12 Little is known about his childhood, though at some point the family moved to Conroe, Texas, just north of Houston. Williams played for the Conroe Pine Knots from 1940-42, and then moved up to semipro ball with the Bay City Oilers. He also played for a local industrial team in Houston called “Morgan Line.”13

As a shortstop he played well enough to be selected to an all-star team of players from Conroe, Baytown, and Houston. That team played a two-game series against a Negro National League all-star team following the 1942 season. Two of those players, Pat Patterson and Houston resident Roy Parnell, played for the Philadelphia Stars.14 After the series, they successfully lobbied the Stars’ owner, Ed Bolden, to sign Williams.

In 1943 Williams split his time between second base and shortstop. He played 13 games for the Stars and had 53 plate appearances, hitting .408/.453/.592.15 Williams had a big night on August 19, going 5-for-5 in a 12-11 win over the Newark Eagles, after he had spent weeks on the bench watching “his lessers failing in the clutch.”16 However, two days later Williams accounted for five of the 20 strikeouts that Birmingham hurler Alvin Gipson registered against the Stars.17 Despite having debuted in midseason, Williams was deemed good enough to play for the Negro National League All-Stars in an exhibition series against the Homestead Grays in September.18

Williams was the full-time second baseman for the Stars in 1944 because, in his words, “Frank Austin could only play shortstop so I had to move.”19 Big things were expected of him, and the Philadelphia Tribune noted that in 1943 he had “won acclaim…of the fans with his infield exploits…Loop experts expect to find him a top performer throughout the season.”20

Williams did not disappoint, hitting .353/.399/.517 and playing in the only East-West All-Star game of his career. In the offseason, he played for Ponce in the Puerto Rican Winer League, where he hit .378,21 second in the league behind teammate Francisco “Pancho” Coimbre. Ponce won the league title by 7½ games.22

After the Red Sox audition, Williams started off hot in 1945, slugging a home run in his first at bat23 and hitting an almost unfathomable .459/.500/.803, including five home runs, in his first 67 plate appearances.24 The Tribune compared Williams and his double-play partner, shortstop Frank Austin, to Negro League greats such as Bus Clarkson, Dick Lundy, and Frank Warfield.25

Later that spring, Jorge Pasquel, who ran the Mexican League, offered Williams a reported $1,500 dollars a month to head south of the border. The Mexican League was making a push for the big time and Pasquel was willing to pay for talent. The league already had recruited a number of Negro League stars throughout the 1940s. Starting in 1946, Pasquel also lured AL and NL players, including Bobby Estalella, Sal Maglie, and Max Lanier.

Williams accepted Pasquel’s offer and jumped his Philadelphia Stars contract to play for the Mexico City Diablos Rojos (Red Devils). The Philadelphia Tribune lamented the loss of Williams, stating that while he was a “sometimes erratic fielder, he was a slugger, a ‘long ball’ hitter.”26 Ed Bolden claimed that Williams and other jumpers owed him $1,000 and declared, “I intend to make a notation at the league meeting to bar contract jumpers forever.”27

Williams hit .362/.407/.633 for Mexico City in 1945. After the season, he headed back to the U.S. and appeared in one all-star game for the North Classic Team. In the winter of 1945-46, he played for Estrellas del Caribe in Venezuela, where he hit .423 with a .673 slugging percentage and led the league with 14 doubles.28 In an exhibition game, Williams went 2-for-3 as the Estrellas defeated a team of American all-stars that included Roy Campanella, Sam Jethroe, Buck Leonard, Jackie Robinson, and Quincy Trouppe. However, he hurt his arm during the game and found himself unable to throw. Williams said that, in 1946, Robinson, who was about to suit up for the Montreal Royals, told him, “Come on back. I know they are going to sign you; I am pretty sure.”29

Philadelphia Stars co-owner Eddie Gottlieb sent Williams to Nuevo Laredo (Mexico) to meet with a doctor who had fixed Kansas City Monarchs pitcher Connie Johnson’s arm. By the time he got there, however, the doctor had left town, and nobody could tell Williams where he had gone. Williams had his arm worked on while rumors spread that the Yankees and White Sox were considering whether to sign him. His first choice was the Yankees, but Gottlieb told him, “The way you are throwing, they aren’t going to move [Joe Gordon], [even though] you can outhit him.”30 However, Williams’ arm never healed properly and white teams backed off when they heard about the injury.

In May 1946 the Negro National League placed a five-year ban on all players who had disregarded their contracts and signed in Mexico for 1945. The ban included future Hall of Famers Ray Brown and Ray Dandridge.31 However, it is unclear whether Williams was on this list. Apparently, the Stars were expecting him back during the season; the Tribune reported that, “Williams will make his peace with the immigration authorities…his being placed on the five-year ineligible list…was erroneous.”32 Regardless, Williams did not return to Philadelphia. His presence was missed and the Tribune ascribed Philadelphia’s inability to “cop the first half bunting” to the absence of Williams and Ed Stone, writing that “they represented the fence-busting backbone” of the Stars.33

Instead Williams played for Vargas in Venezuela alongside Campanella, Jethroe, and Roy Welmaker. Williams hit .339 and led the league in runs (29), doubles (14), and RBIs (41) as Vargas won the title with an 18-12 record.34 He was back in Venezuela that winter, helping Vargas win the league playoffs by hitting .343 with a .559 slugging percentage.35 During the season the club played an exhibition against the Yankees and won, 4-3, as Williams went 1-for-4.

In 1947 Williams played in the Zulian League in Venezuela. He played for traditional power Pastora, but neither statistics nor standings are available.

During the winter of 1947-48, Williams was in Cuba suiting up for the Habana Reds (or Leones) in the Liga de la Federación Nacional. This was an outlaw league that had been organized for those players who had been banned from Organized Baseball for jumping their contracts to play in the Mexican League. The new circuit began the season by greatly outdrawing the traditional Cuban winter league.36 Williams’ ninth-inning home run was the lone run in Habana’s opening-day win. He hit .286 as Habana won the title.37

In 1948 the Negro National League decided to uphold its ban on players who had bolted for Mexico. By then 28-years-old, Williams played for the Mexico City Diablos Rojos once more and hit .328/.410/.583 with 14 homers, 57 RBIs, and a league-leading 11 triples.38 That winter he played for Los Mochis of the Liga de la Costa del Pacífico (Mexican Pacific Coast League). Although statistics for this league are spotty, Williams was one of the team’s offensive stars and one source credits him with 18 RBIs.39

Toward the end of the 1948 season, the Mexican League was struggling as both the Negro Leagues and the American and National Leagues lifted their ban and players headed back to Organized Baseball; the league pared its rosters down to 18.40 Early in 1949 Williams jumped from Jalisco (his Mexican club) back to the Philadelphia Stars of the now consolidated Negro American League (NAL).

Williams celebrated his return by starting hot, leading the league in seven offensive categories after the first week, including a tie in home runs. His .418 average was good for third in the league.41 In early May the Stars swept a doubleheader from the Kansas City Monarchs, with Williams hitting the deciding home run in the nightcap.42 The Philadelphia Tribune singled him out for praise as part of “the most power-laden squad [future Hall of Famer] Oscar Charleston, or any other Stars’ manager, has ever come up with.”43

Despite their fast start the Stars finished fourth in the NAL, far behind the champion Baltimore Elite Giants.44 One reason for the team’s downturn may have been Williams jumping to Venezuela, which left “the Stars in a pretty deep hole.”45 Nevertheless, while he was with the Stars in 1949, Williams hit .330 and slugged .557.46

In the winter he was back with Ponce in Puerto Rico. Although he had a down season, hitting .240 with two home runs, he was still selected to play for the Importados vs. the Nativos in the All-Star game.47

In 1950 Williams started the year with the Negro American League’s Columbus Buckeyes, for whom he batted 250/.344/.321 in 22 games.48 Despite the slow start, Williams was signed by the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League (PCL). The Solons were the AAA team of the Chicago White Sox, though it was Solons owner Jo Jo White who signed Williams, not the White Sox. Williams was the first African American to play for the Solons,49 which became the fifth PCL team to integrate since John Ritchey debuted for the San Diego Padres in 1948.

Despite some fanfare Williams began his career in Sacramento with a strikeout and hit just .250/.313/.450. While he showed decent power, he was not the same hitter he had been from 1943 to 1949, and he left after one year. The Sporting News cited a broken foot he suffered that winter in Mexico,50 but Williams himself remarked that he left because he was not making enough money to live in California.

The stint with Sacramento likely marked Williams’ last opportunity for a career in the AL or NL. At 30 years of age – though he was thought to be 27 – he was not young, and he appears not to have been considered a major prospect. Yet, if he had hit enough, he might have had a better chance in light of his history and reputation.51 Instead he played in only 38 games with the Solons, registering 132 plate appearances. Williams’ experience was commonplace in terms of how slim the margins of opportunity were for African American players at that time. In fact the PCL had only 10 Black players in 1950!

After Williams jumped his contract with Jalisco in 1949, he was banned from the Mexican League. During his time in Mexico, he married Gloria Pacheco.52 In 1950 the family welcomed its first child, Marvin Jr., in Mexico City.53 Williams wanted to be close to his family, so the Mexico City Reds met with league officials and got him reinstated. In spite of its financial troubles in the late 1940s, the Mexican League in 1951 boasted African American talent such as Quincey Trouppe, Max Manning, Buck Leonard, and Wild Bill Wright in addition to Williams.54

After Williams was reunited with his family, he rediscovered his hitting stroke in 1951 and batted .321/.419/.537 with 12 homers and 64 RBIs in 80 games. He went 3-for-3 in the All-Star game that year.55 In the winter he again played for Los Mochis in La Liga de la Costa and hit a league-record 17 homers.56

Although he had both family and success in the Mexican League, Williams was a traveler. In 1952 he signed with Chihuahua of the Class C Arizona-Texas League. The 32-year-old hit .401/.538/.854 with 45 homers and 131 RBIs in just 117 games. This was second best in league and the best among players with 400 at-bats. He was one of just three players in all of Organized Baseball to hit .400,57 and he twice hit three home runs in the same day.58 He was third in home runs in all of Organized Baseball, and the Pittsburgh Courier’s Wendell Smith wrote that he was the “best hitter among all Negro players who performed in Organized Baseball last season.”59 According to Williams, he won the Triple Crown and Spalding Sporting Goods offered him a choice of $50 or golf clubs. He chose the clubs.60

For Williams, the biggest highlight of 1952 occurred on June 25, when he was named Chihuahua’s manager.61 He became only the third African American manager to lead a minor league club, though some reports at the time erroneously claimed that he was the first.62 However, Sam Bankhead and Chet Brewer came first, Brewer by mere months.63 Chihuahua finished the season in last place, and Williams never managed again.

Williams was supposed to play for the PCL’s Oakland Oaks in 1953, but his deal with the team fell through.64 He started 1953 with Laredo in the Class B Gulf Coast League and hit.279/.367/.535. He finished the year with Mexico City, where he batted .373/.469/.529 with two homers and 12 doubles in 40 games. That winter he played with Jalisco (where he hit .336) and Mayos de Novajoa (.309 with 11 homers) of La Liga de la Costa.

In 1954 Williams moved into a new frontier as he played in Canada with Vancouver of the Class A Western International League. According to Williams, he was told that the Mexican League might break up and that he was wanted by the Vancouver franchise. He told the doctor who owned the team that he would not play for less than $700.65 His salary demand was met, and he went north.

Williams spent the full season in Canada and played a starring role on the team at 34 years of age. He hit .360/.439/.601 with 20 homers and 90 RBIs, and even stole 15 bases while playing mostly at second base. Williams won the league’s batting title, and his team won the championship. He was back in La Liga de la Costa that winter playing with Navojoa, where he hit for the cycle on October 24, 1954.66

Williams returned to the PCL with the unaffiliated Seattle Rainiers for 1955.67 Playing mostly at first base, he started well, hitting .308 with five homers and 19 RBIs as of April 27. His play earned him a feature in the The Sporting News titled, “Marv Williams Making up for Lost Time at 32” (he was actually 35).68 The article raved that “[he] whacks the ball sharply to all fields, employing strong wrist action and a loose, whip like swing…it looks as though [he has found] ‘a home.”’69 However, Williams slumped from that point forward and left Seattle after only 35 games.

Williams finished the 1955 season with the Columbia (South Carolina) Reds, Cincinnati’s Class A affiliate in the South Atlantic League. There he regained his form, hitting 328/.415/.556 with 16 homers and 84 RBIs. He was the team’s starting third baseman as Columbia won the regular season title. He played well in the playoffs but was thrown out at the plate on a double in the eighth inning of the game that knocked Columbia out.70 Nevertheless, Williams was one of six Reds who made the league’s all-star team.

One of Williams’ teammates in Columbia was 19-year-old Frank Robinson, who hit .263/.381/.531. In 1956 Robinson set a National League rookie record for homers, but Williams had been the better hitter the year before. Williams demonstrated the mentorship that got him named manager for Chihuahua by teaching the young Robinson to hit the curveball. Asserting that there is no such thing as a good curveball, Williams had Robinson stand at the plate and just watch pitches. After watching numerous curves, Robinson told him that he saw what he meant, which was that the point of the curve was to make him stand up out of his crouch. If he did not stand up, the pitch was either going to be a ball or come right to where he wanted to hit it. The aim was to hit it after it breaks. Later, when Robinson was manager of the San Francisco Giants, he brought Williams into the locker room to visit and told his team, “This is the man who taught me how to hit.”71

In the winter of 1955-56, Williams returned to Navojoa in La Liga de la Costa. The league included a lot of major-league talent that year, including Earl Averill Jr. and Rubén Amaro Sr. Williams won the batting title (.361), but Navojoa finished second and lost in the second round of the playoffs. Williams was selected to the league’s all-star team and was chosen to play with champion Hermosillo in an interleague series against the winner of the “Liga Veracruzana” for the “Championship of Winter Baseball in Mexico.”72 The opposing team included Cleveland star Bobby Ávila. Only one box score is presently available for the series, and it shows that Williams went 3-for-5 as Hermosillo won, 13-3.

Williams spent the next three summers (his age 36-38 seasons) with the Tulsa Oilers of the Class AA Texas League.73 By that time, Williams was a super-utility player, who appeared at first base, second base, third base, and in right field. In his first season, 1956, he hit .322/.394/.562 with 26 homers and 111 runs batted in. He hit .500 in his first 54 at-bats at age 36 and made the all-star team. One of his teammates that year was future Hall of Famer Willard Brown. Brown was 41 at the time and played just 28 games for Tulsa, one of his four teams that season.

In August, Cincinnati obtained an option on Williams’ contract, but nothing came of the deal.74 In 1957, Williams struggled, hitting just .253 with eight home runs. He played that winter with Córdoba in La Liga Veracuzana, and his bat perked up as he hit .332. Returning to Tulsa for 1958, he hit a robust .294/.375/.477 with 19 homers and 88 RBIs. He was hitting .400 well into May and fell just one vote shy of being a unanimous All-Star.75

Williams played five games for the Victoria Rosebuds of the Texas League in 1959 (hitting .400) but then jumped back to Mexico once more. He was a well-known star in Mexico, and he could demand more money. Playing with both Mexico City clubs – the Tigers and Diablos Rojos – Williams hit .310 with 29 homers and 109 RBIs and again made the all-star team.

That winter Williams played alongside former major-leaguer Dan Bankhead for the Puebla Pericos in La Liga Veracruzana and helped the team to the title by hitting .420 and earning yet another All-Star nod. This was Williams’ last season at the top echelon of Mexican baseball, though he continued to play at lower levels until 1963 (statistics for those seasons are not available). In his six full seasons with top-level clubs in Mexico he never failed to bat .300.

In 1960 the 40-year-old Williams was back in the Texas League, where he played for Victoria, a Tigers affiliate, and San Antonio, a Cubs affiliate. In 94 games at first base and in the outfield, he hit .277/.414/.504 with 17 homers.

In 1961 he once again played for two different teams in the Texas League. The first was the Victoria/Ardmore Rosebuds, a Baltimore affiliate; the other was the Rio Grande Valley/Victoria Giants, a San Francisco affiliate.76 He played at first and third base and posted a .278/.386/.418 line.

After the 1963 season, Marvin Williams’ playing career ended. He had developed sinus problems that caused him trouble outside of Texas’ climate, so he decided to settle there. Rosebuds owner Tom O’Connor helped him find a job. O’Connor found Williams working part-time in a Sears, and promised to buy freezers and refrigerators for his ranch if they would hire Williams full-time.77 Sears management agreed, and Williams spent the next 20 years working for Sears – 10 in Victoria and 10 in Conroe – before retiring.

Williams lived quietly after baseball and rarely talked about his baseball career until late in his life. In fact, until he was in his 70s, his sons (Marvin Jr. and Billy) never really knew just how good he was, only that he had played. Marvin Williams died on December 23, 2000, in his hometown of Conroe and was buried in Rosewood Cemetery. His wife Gloria passed away in June 2021.

Williams’ story is an intriguing one. Older Black players got little or no chance in the AL or NL, of course, but subsequent research has provided a good picture of the quality of their play and their careers. The generation younger than Williams – players such as Willie Mays, Henry Aaron, Frank Robinson – was able to get to the top level at a young enough age to have full careers. Williams, on the other hand, was part of a generation of players who were still in their primes as the Negro Leagues declined after the onset of baseball’s integration in 1947. Many of these players never received a fair opportunity to make it onto a team in the AL or NL.

It is possible that Williams missed out on such an opportunity when he left for Mexico in 1945. However, even if this were the case, Williams could not have foreseen what was to come. Williams said that he did not feel badly about not playing in the American or National League because so many Black players did not have a chance at all, while he had played for affiliated minor-league teams. He was a man who enjoyed his life and did not let the injustices he faced get him down. Williams had no regrets, saying, “Yeah, I’d go back and do the same thing over and over.”78

A career such as Williams’ can be difficult to assess because he played in leagues many fans have never heard of. He was certainly a good player – a two-time Negro National League all-star who put up big numbers in the minors and the Mexican leagues. When asked about his hitting prowess, Williams, always humble, said, “If you didn’t produce, they would cut you and send you home. I was a ballplayer and did not want to go home.”79 He routinely hit over .300 and probably belted over 400 homers in a career stretching from 1943 to 1961.80

One way to look at this is to translate his play using Major League Equivalencies (MLEs), which attempt to estimate a player’s stats in MLB using stats in other leagues. One prominent set of MLEs has Williams hitting .286/.359/.466 with 295 home runs and 2,547 hits.81 These are only estimates, but they paint a picture of a player with star level talent, perhaps similar to offensive-minded second basemen like Jeff Kent or Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri.

Remembering players like Marvin Williams is important to understand not just baseball in the 1940s and ’50s but America itself. While it is certainly unjust that he never got an opportunity to have the major-league career estimated above, it is still worth celebrating the notable and accomplished career that Marvin Williams did have.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello, Gregory H. Wolf, and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

Unless otherwise indicated, all Negro, Mexican, and Minor League statistics are from baseball-reference.com. Seamheads.com Negro Leagues database combines Williams’ play in all-star games and the Stars in 1943 and 1944 and Mexican and Negro League performance in 1945. Baseball Reference splits these out.

Notes

1 Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 25, 1959: 22.

2 Wendell Smith, “Red Sox Candidates Waiting to Hear from Management,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 28, 1945: 12.

3 Wendell Smith said that Cronin “tried to withhold his opinion” but when he finally spoke, he “searched cautiously for the right words so as not to be misquoted or subject himself to the fiery wrath of baseball high commissioner: the late Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.” Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 10, 1952: 14.

4 Brent Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000), 177.

5 The idea of a sham is taken from Kelley’s interview with Williams (Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 176). Wendell Smith had this to say: “Isn’t it strange that Boston, of all the teams in the major leagues, has not yet been able to find a ‘capable’ Negro player? Isn’t it strange, too, that Mr. Cronin, now president of the American League, never recovered sufficiently form that broken leg to do anything at all about Robinson, Jethroe, and Williams?” [It was stated in a letter to Smith that Cronin had broken his leg, which threw their planning out of gear for some time.] Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 25, 1959: 26.

6 The source for the Braves’ aborted tryout and FDR’s death stopping it (as well as the date of the Red Sox tryout) is Williams’ interview in Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited. However, Williams was talking years later and had a penchant for stretching the truth.

7 Sam Jethroe later sued MLB for a pension on the basis that he was only turned down in 1945 because he was Black and if given credit for that time he would qualify. “MLB Owes Pension,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 2, 1994: 7C. The suit was dismissed in 1996. Bill Nowlin, “Sam Jethroe,” SABR BioProject: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/sam-jethroe/.

8 Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” April 25, 1959: 26.

9 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Marvin ‘Tex’ Williams,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, https://www.cnlbr.org/. Last accessed February 5, 2023.

10 While the AL and NL were integrating, there were often unspoken quotas – teams would limit the number of Black players on their roster. The fear was that white fans would not turn out if the team was “too black.” Later experience showed that this was mostly an excuse for owner and executive racism.

11 Williams’ obit and his CNLBR bio have his birth year as 1923. So does Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933-1962, Volume II (Chatham, New Jersey: Bowker, 2020). It appears that Williams lied about his age to appear younger and therefore more attractive to prospective teams. However, research on ancestry.com shows a 1930 census with a 10-year-old Marvin Williams. This date is also on his gravestone. Thanks to Kevin Johnson for helping with this.

12 According to Social Security documentation, Williams’ parents were Fred and Eva. It’s possible that his mom’s maiden name was Gainus, as there is evidence of a Marvin Williams raised by a Fred Williams and Eva Gainus, but without an exact birthdate on ancestry.com.

13 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 1.

14 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 175.

15 This data is from https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1943&teamID=PS&LGOrd=1. Retrosheet (https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1943/Bwillm1071943.htm) records 14 games with the Stars but there is no box score and no recorded at-bats for one of them (Williams is credited with 2 hits and a home run). This is likely to change as more information comes in.

16 Frank Lynn, “Stars Win Thriller, 12-11: Shortstop Williams Bats 1000,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 28, 1943: 13. According to Retrosheet this game took place on August 19, though Lynn’s article gives the impression that it was the 26th. See https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1943/Bwillm1071943.htm

17 “Ala. Team Defeats Stars 5-1,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 28, 1943: 13. As noted above, Williams had a penchant for stretching the truth. For instance, when asked by Kelley (176) who the hardest pitcher he faced was, he mentioned Paige and Dihigo. However, he also mentioned Bob Gibson. According to Williams, Gibson, then pitching for the Birmingham Black Barons, struck him out four times in a game. Williams told Gibson that he would get back at him, but Gibson was in the majors before Williams got the chance. The problem is that Gibson never played in the Negro Leagues or any other league in which Williams played. There is no evidence of a barnstorming tour either, though that cannot be ruled out. So, either Williams was misremembering or embellishing, but it is unlikely that his story about Gibson was true. Thank you to Kevin Johnson for finding this game and for Frederick Bush and Phil Dixon for helping think this through on Twitter.

18 See https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1943/Bwillm1071943.htm

19 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 176.

20 “Elaborate Program for Philly Stars’ Opener,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 6, 1944: 10.

21 These stats are from Marvin Williams page on Negro Leaguers in Puerto Rico: https://negroleaguerspuertorico.com/player/marvin-williams/

22 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 4.

23 W. Rollo Wilson, “Thru the Eyes of,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 12, 1945: 16.

24 Seamheads has him worth 1.3 WAR in only 67 PA for that year.

25 W. Rollo Wilson, “Thru the Eyes of,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 2, 1945: 12.

26 W. Rollo Wilson, “Lure of Mexico Proves Irresistible to Pair,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 30, 1945: 13.

27 Wilson, “Lure of Mexico Proves Irresistible to Pair.”

28 Revel and Munoz, Forgotten Heroes, 11.

29 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 177. This is in Williams’ words.

30 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 177-78. Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 11. This story does not quite line up because he continued to play through the injury. Also, why would the owner of the team whose contract he jumped (leading to a ban from the league) be giving him advice on a move to a third league? In fact, Williams’ relationship with the Stars is unclear. As the 1946 season approached, the Philadelphia Tribune claimed that he would be the starting second baseman. “After 42 Years in P.O. Ed Bolden Retires, To Spend Time with Stars,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 20, 1946: 11.

31 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 12. Hall of Famer Leon Day was also suspended but is not mentioned here. Wild Bill Wright was another prominent player who was suspended.

32 Randy Dixon, “Boldenmen Well Fortified for Second Half Struggle,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 9, 1946: 12.

33 Randy Dixon. “Sports Bugle: The Halfway Mark,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 9, 1946: 10.

34 This stat line and Williams’ status as a league leader were pieced together from three sources: James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994), 858; Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 12: Registro Histórico Estadistico del Beisbol Profesional Venezelano (https://pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=willmar001).

35 Registro Histórico.

36 Rene Canizares, “Cuban Outlaw Loop Opens Before 36,000, Rival Draws Only 3,000 the Same Night,” The Sporting News, November 12, 1947: 21.

37 Thanks to Phil Selig and Eric Chalek for this info.

38 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 15.

39 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 16.

40 Jorge Alacron, “Six Mexican Loop Players Jump to O.B.,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1948: 29; Jorge Alacron, “Mexican Clubs Reel Toward Finish line with Pared Rosters,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1948: 31.

41 “Easterling Tops N.A.L. Batters: Stars’ Marv Williams in Third Place,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 24, 1949: 11.

42 “Stars Defeat Monarchs Twice for N.A.L. Lead,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 10, 1949: 11.

43 Kimmie Debnam, “Sports-I-View,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 21, 1949: 11.

44 “Negro American League Standings (1937-1962),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research: https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20American%20League%20(1937-1962)%202016-08.pdf

45 Kimmie Debnam, “Sports-I-View,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 30, 1949: 14. This is the only source for Williams’ jumping to Venezuela; Revel and Muñoz do not mention it. As such, no stats are known. However, when Williams signed with Sacramento in 1950, his last club was listed as “Maracaibo in Venezuela.” “Joins Solons,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 29, 1950: 11.

46 Howe News Bureau, ‘Negro American League (1949) League Leaders.’

47 Negro Leaguers in Puerto Rico; Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 18.

48 Revel and Muñoz also report that he played in Venezuela during the 1950 season, though no other corroboration of this could be located. It is possible they are referring to his stint in 1949 mentioned above.

49 “Joins Solons,” Philadelphia Tribune. Williams was also signed alongside of Walter McCoy: John R. Williams, “Sacramento Signs Two Negro Ball Players,” Chicago Defender, September 2, 1950: 17.

50 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, February 28, 1951: 28; Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 176.

51 Or, given the fortunes of players like Bus Clarkson, it may never have been enough.

52 Date uncertain – marriage certificate could not be found on ancestry.com.

53 Son’s birth certificate on Ancestry.com.

54 “U.S. Negroes on 6 Teams in Mexican Loop,” Chicago Defender, May 26, 1951: 17.

55 Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, 858.

56 The previous record was 13. “Mexican Leader, Ciudad Obregon, slides to 5th,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1952: 28.

57 Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 28, 1953: 24.

58 “Tipping the Skimmer,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1952: 38; “Tipping the Skimmer,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1952: 37.

59Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 28, 1953: 24.

60 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 176.

61 “Skipper Shifts,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1952: 52.

62 A 1952 story from Phoenix had Williams as the first – see “Marvin Williams is Named Manager,” Anderson Daily Bulletin, June 26, 1952. By another account, Williams was second. “Marvin Williams to Pilot Chihuahua Club,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 15, 1952: 2.

63 Sam Bankhead was the first in 1951 for the Class C Farnham Pirates of the Canadian Provincial League: Dave Wilkie, “Sam Bankhead”, SABR BioProject (https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/sam-bankhead/), accessed September 4, 2023. Chet Brewer took over the Riverside Comets of the California League in 1952: Thomas Kerna and Bill Staples Jr., “Chet Brewer” SABR BioProject (https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/chet-brewer/), accessed November 18, 2023.

64 Lenny Anderson, “Marv Williams Making Up for Lost Time At 32,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1955: 17.

65 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 177.

66 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 25.

67 This was right before the Dodgers and Giants moved west and right after the PCL attempted to rise above AAA status. It is classified as ‘OPN’ in Baseball-Reference.

68 Anderson, “Marv Williams Making Up for Lost Time At 32.”

69 Anderson, “Marv Williams Making Up for Lost Time At 32.”

70 “Columbia Drops from Playoffs,” Greenwood (South Carolina) Index-Journal, September 2, 1955: 2.

71 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 179.

72 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 31.

73 During his stay Tulsa changed from being a Cubs farm team to a Philadelphia affiliate.

74 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 33.

75 Bill Rivers, “Cats Purring Along on Smooth Hurling,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1958: 39.

76 See the Texas League page on BR Bullpen for Franchise locations: https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Texas_League. In 1960, Victoria Rosebuds owner Tom O’Connor Jr. relinquished control of the team (see Charles D. Spurlin, “A Brief History of Baseball in Victoria,” Victoria Generals Website: https://victoriagenerals.com/briefhistory/). The Rosebuds moved to Ardmore, Oklahoma during the 1961 season. They were replaced by the struggling Rio Grande Giants that same season. It is possible that Williams was either traded or that he just stayed in Victoria and began playing with the Giants when they arrived. Either way, both the Rosebuds and the Giants were out of the Texas League in 1962.

77 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 178.

78 Kelley, Negro Leagues Revisited, 178.

79 Revel and Muñoz, Forgotten Heroes, 41.

80 One could argue that it lasted from 1941 (when he began playing locally in Conroe) until 1963 (when he finished playing in the Mexican minor leagues).

81 These were created by SABR member Eric Chalek and are accessible at horsehidedragnet.com. This is the version released in the summer of 2023.

Full Name

Marvin Williams

Born

February 12, 1920 at Haslam, TX (USA)

Died

December 23, 2000 at Conroe, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.