Adrian Beltré

At first glance, Adrian Beltré’s path seems predictable. Sought after at a young age, he instantly became a highly touted prospect who plowed through the minor leagues and reached the majors before he turned 20. Over the course of 21 seasons (1998-2018), he earned more than $200 million through multiple multi-year contracts. In 2018, The New Yorker declared, “In box scores, Beltré appears almost boringly steady.”1 However, while there are thousands of adjectives that could accurately describe Beltré’s baseball life, “boring” isn’t one of them.

At first glance, Adrian Beltré’s path seems predictable. Sought after at a young age, he instantly became a highly touted prospect who plowed through the minor leagues and reached the majors before he turned 20. Over the course of 21 seasons (1998-2018), he earned more than $200 million through multiple multi-year contracts. In 2018, The New Yorker declared, “In box scores, Beltré appears almost boringly steady.”1 However, while there are thousands of adjectives that could accurately describe Beltré’s baseball life, “boring” isn’t one of them.

For one thing, Beltré wasn’t as lauded as one might expect. Although he recorded more hits (3,166) than any third baseman in major-league history, won five Gold Gloves, and four Silver Sluggers, Beltré was selected to only four All-Star teams and finished in the top six of his league’s MVP voting just twice.

Yet, by the time he walked away from the game, Beltré had become one of the most beloved, joyful players of his generation. His presence touched countless fans and players alike. Shortstop Elvis Andrus, Beltré’s teammate for eight years in Texas, wrote on Instagram, “Thank u [sic] for everything you’ve done in my career in and off the field and for always teach[ing] me to believe in myself, respect the game and the most important…enjoy the game.”2 Hall of Famer Chipper Jones, the contemporary to whom Beltré was often compared, called him the “total package at the hot corner” and vowed to “save [him] a seat at the third baseman’s table of the members dinner in Cooperstown.”3

In 2024, Beltré became the fifth Dominican-born player to be enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame, earning 95.1% of the votes cast by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

Even before Adrian Beltré Pérez was born, his dad, Bienvenido, thought that he and his wife, Andrea Pérez, had something special on the way. As legend has it, Bienvenido told his friend, Dominican baseball legend Felipe Alou, that his pregnant wife would give birth to a great ballplayer. Bienvenido, nicknamed “El Negrito”4 because he was dark and handsome, would train him to be a star, and Alou could help mentor him.5 On April 7, 1979, Adrian entered the world in Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic.

Bienvenido had built the family home in the Café de Herrera neighborhood, in the southwestern sector of the city. He was an industrial mechanic who trained roosters for cockfighting, a popular and legal sport in the country. He was also a professional baseball player.6 His son followed him everywhere. “He would take me to the fields [to] watch him play,” Beltré said. “He was a big influence on my life.”7 When Alou managed in Dominican winter ball, he took young Adrian with him. “I thought he’d be asleep after the game,” Alou recalled. “I was surprised that he was awake. He talked about the game all the way back.”8

Despite being a scrawny youngster, Beltré loved playing baseball like his dad. He found ways to get games going with friends even without proper equipment. “We [were] very creative,” Beltré said. “We find a way to keep ourselves entertained and make baseball out of anything – a sock, a tennis ball, anything we have to create a baseball game.”9

Shortly after Beltré turned 11, his father introduced him to Franklin Rodríguez, who operated a baseball school on the grounds of the Hogar Escuela Santo Domingo Savio. (Beltré was a student at the Escuela Rafaela Santaella, not the Liceo Máximo Gómez as some reports indicate.) Over the ensuing quarter-century, more than 200 of Rodríguez’s pupils signed professional contracts, including D’Angelo Jiménez, Melky Cabrera and Edinson Vólquez. “He [Beltré] had strength in his arm and hit the ball very hard,” Rodríguez recalled in Spanish.10

At the time, Beltré also loved basketball and tennis. In 1991, however, he watched a Houston Astros game on a grainy television set and decided he wanted to be like their slick-fielding third baseman. “Ken Caminiti,” he explained. “I saw how hard he played. I saw the plays he made, and I got serious about baseball.”11

Los Angeles Dodgers scout Pablo Peguero donated balls and other supplies to Rodríguez’s camp, so Beltré wound up in that organization’s pioneering workout facility in 1994.12 Although Beltré weighed only 130 pounds, Peguero and fellow scout Ralph Ávila spotted him and fell in love with his rocket arm13 and lightning line drives. The pair insisted that the Dodgers offer him a contract as soon as possible. Even though Beltré was only 15 – a year younger than the minimum age – the Dodgers signed him for $23,000 on July 7, 1994, using documents that recorded his birth year as 1978. “I often tell players… once you sign, you’re not going to be a kid any longer. You are a professional,” Alou said. “His dad really coached him to be a pro.”14

Beltré developed his talents at the Dodgers’ Campo Las Palmas complex and made his professional debut in the Dominican Summer League in 1995. He batted .307.15

Upon arriving in the United States in 1996, Beltré skipped rookie ball and became the youngest player in the Class A South Atlantic League when he was assigned to the Savannah (Georgia) Sand Gnats. “I lived with several Latinos, and they did not speak English, so we adapted little by little. We started by ordering food at McDonald’s or at Subway after the game,” Beltré said. “What helped me was arriving at the place, pointing at a photo [of food], saying something as if I were murmuring, letting them answer me, and saying ‘yes.’ But I didn’t know what they were going to give me… I went hungry a lot because I’ve always hated pickles… I’d immediately throw it in the trash.”16

On the field, Beltré blasted through his competition. Based on his .307/.406/.586 slash line in 68 games with Savannah, he was named the league’s best prospect.17 He was promoted to the High-A California League and finished the season with the San Bernardino Stampede. Between the two clubs, he produced 26 homers and 99 RBIs in 131 games.

In 1997, Beltré batted .317 for the Vero Beach Dodgers and led the High-A Florida State League in homers (26), RBIs (104) and slugging (.561). He was voted the circuit’s MVP. Baseball America exclaimed, “He hasn’t shown any weaknesses in two years of minor-league ball.”18 Beltré struggled with the glove, making 37 errors on 351 chances that season. But he would soon be considered one of baseball’s best defenders.

Entering 1998, Baseball America ranked Beltré as the majors’ number-three prospect.19 He started the year with the San Antonio Missions, where he was five years younger than his average competitor in the Double-A Texas League. Over 64 games, he hammered 13 homers and batted .321. It seemed only a matter of time before he starred at Chavez Ravine.

On June 24, 1998, Beltré was called up and given a seat at “the table of baseball’s most dysfunctional family.”20 The Dodgers were in the midst of a tumultuous season, having fired their manager and general manager three days before Beltré’s arrival. Future Hall of Famer Mike Piazza had been traded away in mid-May. Beltré’s opportunity came, in part, because one of the players obtained for Piazza – third baseman Bobby Bonilla – had just gone on the disabled list with an intestinal infection. “What’s too soon?” asked former Dodgers skipper Tom Lasorda, who had just assumed the club’s interim GM duties. “The kid has got talent, and he’s got everything he needs to be here.”21

In his first at-bat, Beltré roped an RBI double down the left-field line off Anaheim Angels starter Chuck Finley to announce himself to the big-league world. “I was really nervous,” he said. “I had a butterfly in my stomach… I was thinking, ‘Whatever he throws me I’m going to swing at it because I can’t feel my body.’ It’s like I was floating.”22 He also singled before the contest was over. Six nights later in Texas, he hit his first home run.

Although Beltré hit only .215 with seven homers in 77 games, he remained with L.A. for the rest of the season. His place as the team’s starting third baseman was secured that fall when new Dodgers GM Kevin Malone shipped Bonilla to the New York Mets to make room for “one of the game’s best prospects.”23

That offseason, Beltré played winter ball in his native country for the third straight year. He had hit .219 in 76 games for the La Romana-based Azucareros del Este over his first two campaigns. However, playing for Santiago-based Águilas Cibaeñas in 1998-99, he batted .301 with 10 homers in 58 games to win Dominican League MVP honors. The Aguilas were eliminated in the playoff semifinals, but Beltré accompanied the champion Tigres del Licey to the Caribbean Series in San Juan, Puerto Rico. There he made the all-tournament team and helped the Dominican Republic prevail.

In 1999, Beltré appeared in 152 games for the Dodgers and hit a moderate .275 with 15 homers. During spring training, he had informed his agent, Scott Boras, that he was 19 years old rather than his listed age of 20. Realizing Beltré was underage when he first signed with the Dodgers, Boras initially offered to drop the matter if the club offered compensation. When the team refused, Boras pushed Major League Baseball to allow his client to become a free agent, as other Latin-born players who were signed too early had. After an investigation, Commissioner Bud Selig ruled that Beltré – despite his denials – knew his birth year had been altered on certain documents. Beltré was ordered to remain with the Dodgers but awarded the difference between the signing bonus he received and what he could have made one year later ($48,000). Selig also fined the Dodgers $50,000, shut down their Dominican baseball operations for one year, and suspended scouts Ávila and Peguero.24

Beltré joined the San Pedro de Macorís-based Estrellas Orientales for the last eight regular season Dominican League games in 1999-2000. In 25 playoff contests, he notched 29 RBIs and batted .300 with seven homers, including three in the seven-game final series. The Estrellas lost to the Aguilas, but Beltré was named the finals MVP anyway.25

In 2000, Beltré increased his production to a .290 batting average with 20 homers and 85 RBIs for the Dodgers. Still just 22, he seemed primed to take an even bigger leap the next season. Instead, he ran into a strange and life-threatening wall.

That winter, Beltré underwent a botched appendectomy in the Dominican Republic, resulting in a serious infection and additional surgery. He was flown back to Dodgertown in Vero Beach in February 2001 and struggled through a slow recovery. He lost 15 pounds and was attached to an IV bag until nearly March. “When they opened me up, my appendix had already burst,” Beltré recalled. “You can’t even imagine how close I was to death. It was the scariest time in my life, by far.”26

Beltré made his season debut in early May but never got it going. He finished the season with a .265 batting average and a .310 OBP. Whether owing to the debilitating infection or not, Beltré’s woes continued to haunt him over the next two seasons. He scuffled to a .257 batting average in 2002, and bottomed out at .240 in 2003, with a disappointing .290 OBP (both career-lows as a full-timer).

The Dodgers grew impatient, and criticisms of Beltré’s play went public. It was written in the Los Angeles Times that “he was a ‘5 o’clock hitter,’ incapable of translating batting-practice power into games. He allowed emotion to overwhelm him.” As Beltré later recalled, “They also thought I was going to get fat.” (He was listed at 5-foot-11, 220 pounds later in his career.27) Heading into his contract year, a rumor percolated that offseason that Beltré might be dealt to the Yankees to replace Aaron Boone. The talks died when New York acquired Alex Rodríguez instead.28

With everything to prove, Beltré enjoyed an uncharacteristically hot start in 2004, batting .478 with three homers in the season’s first week. He had been a .227 and .247 career hitter in May and June, respectively, up to that point, but he kept producing as the calendar progressed. Beltré entered the break with 22 home runs (one off his previous career-high) and a .315 batting average, but he was left off the All-Star team in favor of Scott Rolen and Mike Lowell. “If Belly can continue with the hot start,” said teammate Shawn Green, “he’ll be able to really relax and do what he does in the second half of the season.”29 That’s exactly what happened.

After the snub, Beltré got even hotter. By season’s end, his.334/.388/.629 (1.017 OPS) slash line established career highs across the board. He also achieved personal bests in homers (a NL-leading 48), RBIs (121), runs scored (104), hits (200), and fielding percentage (.978). In September, the Dodgers clinched their division to end the franchise’s longest postseason drought (eight seasons) since they’d relocated from Brooklyn in 1958. Beltré was named the National League Player of the Month. “Remember when the Dodger fans chanted ‘M-V-P’ for me last season?” Beltré asked the following year. “Every day during the last month? I was thinking those chants were better than the award itself.”30 As it happened, he garnered six first-place votes in MVP balloting but finished second to the Giants’ Barry Bonds, the only major leaguer to exceed Beltré’s 9.6 WAR.

The Dodgers were defeated by the St. Louis Cardinals in a four-game NLDS in which Beltré went 4-for-15 without an extra base hit.

Shortly thereafter, he became a prized free agent; on December 17, 2004, Beltré signed a lucrative five-year, $64 million deal with the Seattle Mariners. Not usually a major player in free agency, Seattle had lured one of the biggest fish to join a contending club that had won at least 91 games for four straight seasons. “The bottom line is, the Dodgers didn’t want to sign me,” Beltré said. “If they had only talked to me and told me their plan, I would have signed for less money to stay there.”31

Years later, Beltré reflected, “I wanted to stay [in LA] forever… Everything happened for a reason.”32 During his time with Seattle, that reason wasn’t entirely clear, as he sank back into obscurity with a team that missed the playoffs in each of his five seasons. In 2005, Beltré lost his ability to punish fastballs, and his numbers showed it. He batted .255 (his lowest mark since his rookie year) with 19 homers and a .716 OPS.

When Beltré made his first trip to Dodger Stadium as a visiting player on June 20, 2006, he slammed a first-inning home run. “I thought I was going to get booed more loudly than [I was],” he said. “I just went up there trying to get a good pitch and hit a line drive somewhere. I tried not to strike out. I didn’t want to get booed again.”33 Asked if he might have struggled as badly if he’d stayed in Los Angeles, Beltré replied, “Probably not.”34

Though he didn’t approach the heights he’d attained in 2004, Beltré improved to .268 with 25 homers in 2006, closer to his average production. His high points included a two-homer game against the Yankees in August, and a five-RBI performance against Kansas City in September. He continued to play his usual stellar defense at third. Still, given the expectations of a big contract and his new team’s consecutive fourth place finishes, Beltré’s time in Seattle was ranked “somewhere between disappointment and disaster” by Bill Shaikin of the Los Angeles Times.35

In 2007, the Mariners enjoyed their only winning season during Beltré’s time with the team, finishing 14 games above .500. On May 28, Beltré tied a franchise record with four extra-base hits (two home runs and two doubles). Overall, he had his best season with Seattle: .276 with 26 homers and 99 RBIs. He also received some long overdue recognition when he was awarded his first Gold Glove.36

Beltré’s bat stayed consistent, but the Mariners regressed in 2008. Seattle finished fourth for the third time in four seasons while Beltré managed 25 homers but just 77 RBIs with a .266 average. On September 1, he hit for the cycle, and his defense was better than ever. Per Baseball-Reference, Beltré’s major league-leading 3.1 dWAR was the third-highest among third basemen in the 2000s. He received his second consecutive Gold Glove.

The 2009 season, the final one on Beltré’s contract, was painful. He was hitting .259 with only five home runs in 73 games when he underwent surgery to remove a bone spur from his non-throwing shoulder on June 30. Expected to miss up to eight weeks initially, he returned on August 4 looking like his old self, batting .390 over 41 at-bats. On August 12, however, a laser groundball kicked up and caught him in the groin. Beltré wasn’t wearing an athletic cup and suffered a ruptured testicle. “When I look down, after the game, it wasn’t a pretty sight,” he said. “My testicle got the size of a grapefruit. Thank God it didn’t really damage anything.”37

After a stint on the disabled list, he returned on September 1, still without a cup. “They say I’m crazy,” Beltré said. “But I say, if the ball’s going to hit me there every 11½ years, I’ll take my chances.”38 Egged on by Ken Griffey Jr., the Mariners’ public address system played The Nutcracker Suite before Beltré’s return at-bat.39 Overall, Beltré played only 111 games in 2009 and batted .265. The eight home runs he mustered were the lowest full-season total of his career.

Through the life of his contract with Seattle, Beltré averaged only 20 homers, a .266 batting average, and a mediocre .317 OBP. John McLaren, the Mariners’ manager for parts of two of those seasons, believed Safeco Field’s spacious dimensions “got in his head.”40 Beltré said he realized during his last years in Seattle that he needed to “stop taking everything so seriously…It was when I learned how to enjoy the game that my talent took off a little bit more.”41

With the Mariners, Beltré endeared himself to his teammates as a friend and inspiring leader. He and Seattle pitcher Félix Hernández developed a relationship that carried over the next decade. The day after Beltré recorded his 3,000th hit in 2017, for example, Hernández walked off the mound to wrap him in a hug at home plate.42

In December 2009, Beltré turned down the Mariners’ one-year, $12 million arbitration offer and chose to test free agency instead. The risk didn’t immediately pay off – it seemed that most clubs believed the 30-year-old third baseman’s best days were behind him. Beltré settled for a one-year, $9 million deal with the Boston Red Sox.43

With Boston, Beltré exploded for his highest batting average (.321), OBP (.365), homers (28) and RBIs (102) since his 2004 career season. With the help of the Green Monster at Fenway Park, he cranked a career-high and American League-leading 49 doubles. The Red Sox missed the playoffs, but Beltré was named to his first All-Star team, won his second Silver Slugger Award, and finished ninth in MVP voting.

Off the strength of his 2010 campaign, Beltré signed a six-year, $96 million contract with the Texas Rangers in January 2011. The Rangers were coming off the first World Series appearance in franchise history and hoped that Beltré’s veteran presence would get them over the top.

Part of the deal allowed Beltré to wear his preferred uniform number 29, which had belonged to outfielder Julio Borbón. Beltré also agreed to donate $100,000 per season to the Rangers Foundation, dedicated to improving the lives of the community.44

Rangers manager Ron Washington, a former big-league infielder, said Beltré’s hands were the key to his outstanding defense, explaining, “Beltré does a lot flat-footed, and it’s all in his hands. A line drive will get hit to him, and you’re going, ‘Dang it, he’s in the wrong position.’ And the ball will hit in his hands. He comes to a complete stop before he throws the baseball. That’s why he can throw that ball from all kinds of angles. You wouldn’t teach [Beltré’s] style of play. But he’s pretty dang good.”45

Beltré started the All-Star Game for the first time in his first year with Texas. But he strained his hamstring 10 days later and went on the disabled list for six weeks. When he returned in September, he won AL Player of the Month honors after homering 12 times in 15 games. The Rangers won a franchise record 96 games and clinched their division. Beltré completed his second straight stellar season, batting .296 with 32 homers and 105 RBIs.

In Beltré’s first trip to the playoffs in seven years, he sealed Texas’s ALDS triumph over the Tampa Bay Rays by homering three times in a 4-3 victory in the clinching Game Four. Although six players before him had gone deep three times in a postseason contest, Beltré became the first to do it in a game that his team won by one run.46 He batted a light .222 in the ALCS against the Detroit Tigers, but his RBI single off Max Scherzer gave the Rangers a lead that they never surrendered in the decisive Game Six.

Next, the Rangers met the St. Louis Cardinals in a classic seven-game World Series. Beltré hit safely in five of the first six contests, including a four-hit performance in Game Three. In Game Five, Beltré secured his place as a Rangers legend by hitting what is arguably the most iconic home run in franchise history.47 With the series tied and his team down, 2-1, with two outs in the bottom of the sixth, Beltré went down on one knee and launched an 0-1 pitch from Cardinals ace Chris Carpenter over the left field fence. The homer tied the game and ignited the Rangers’ 4-2 victory. Unfortunately, St. Louis won the next two games to capture the title. Beltré went 0-for-3 in the Rangers’ 6-2 defeat in Game Seven.

Beltré took the loss personally. “I’m trying to get over it,” he said that winter while accepting his third Gold Glove and Silver Slugger awards. “It’s hard. Hopefully, when I get to spring training, it’ll be all gone.”48

In 2012, Beltré extended his consistency. Fans voted him an All-Star Game starter, and he clobbered 36 homers, drove in 102 runs, and batted .321. On August 12, Beltré’s seventh-inning single off Twins reliever Kyle Waldrop completed his second career cycle. Beltré earned his fourth Gold Glove and finished third in MVP voting. The Rangers won 93 games but finished second to Oakland and lost the inaugural Wild Card game to the Baltimore Orioles.

After being afforded relative anonymity in Seattle, Beltré became a household name in Texas as the baseball’s social media universe developed and his myriad of personality quirks became apparent. Most notably, it became known that Beltré had a serious aversion to having his head touched. “I’ve never liked people touching my head, not even my kids,” he explained in 2012.49

As clips and gifs surfaced of his teammates – especially Elvis Andrus – playing the part of mischievous little brother and playfully touching his head, Beltré’s reputation as an idiosyncratic elder statesman grew. “Like a great silent-film performer,” The New Yorker wrote, “Beltré told entire stories with simple facial expressions – incredulity, disgust, disappointment, or an angry stare that would occasionally break into a secret smile, as if the game of baseball were an extended private joke inside his own head.”50

Beltré also became known for his violent swings that spun him into pretzels, sometimes knocking off his helmet, and other times resulting in home runs while down on one knee. He also had a playful rapport with teammates and opposing players alike. When Victor Martínez hid Beltré’s helmet before a game, Beltré joked, “I thought about killing him…but I have a family, so I didn’t.”51

Beltré’s antics became the stuff of legend, and he never ceased adding new acts to the list. He made highlight reels by throwing his glove at a ball that screamed past him down the line52, swatting Miguel Cabrera in the midsection when he dared go for his head53, and dragging the on-deck circle after being warned by the umpire to stand on it. For the on-deck incident, the umpire ejected him. “I wasn’t being funny,” Beltré said. “He told me to stand on the mat, so I pulled the mat where I was and [stood] on it. I actually did what he told me. I was listening.”54

On the field, Beltré remained a model of consistency from 2013 to 2016, averaging .307 with 25 homers and 89 RBIs. He led all third basemen in hits and batting average during that period. In 2014, he made his fourth and final All-Star appearance and won his fourth Silver Slugger. In 2016, he led all third basemen in defensive runs saved and captured his fifth Gold Glove.

On May 15, 2015, Beltré became the fifth third baseman in MLB history to hit 400 homers55 when he took Bruce Chen deep to dead center during an 8-3 Rangers loss. The team unfurled a congratulatory banner in the outfield. “I don’t like those situations but it was nice for the fans,” Beltré said. “The banner was nice, too, but would have felt a lot better if we won the game today.”56 That summer, Beltré’s fifth-inning home run off Mike Fiers on August 3 clinched his third career cycle – a feat that hadn’t been accomplished in 82 years.57 After the game, Beltré joked, “When you’re fast like me, it’s not that difficult.”58

Prior to the 2016 season, the Rangers tacked two additional years (each valued at $18 million) onto the end of Beltré’s original contract, taking him through 2018 with the club.

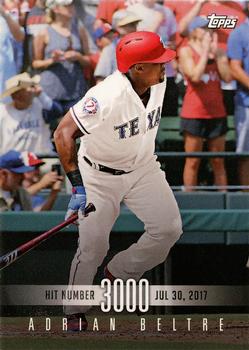

Beltré entered 2017, his 20th big-league season, just 55 hits shy of 3,000. On July 4, he became the 17th player ever to collect 600 career doubles. Three days later, he became the 21st player to amass 5,000 total bases. Finally, on July 30, Beltré laced a line drive into left field off Orioles’ starter Wade Miley for his 3,000th hit, becoming the first Dominican-born player to reach the milestone.

One of the few disappointments that Beltré experienced in 2017 occurred on the Players Weekend of August 25-27, when nicknames were permitted on the backs of uniform jerseys. Because of copyright issues, Beltré was not allowed to use “Kojak,” the nickname his uncle gave him in tribute to the baldheaded 1970s television detective played by Telly Savalas. Instead, Beltré’s uniform featured the shortened “El Koja.”59

Beltré showed signs of wear in 2018 as the Rangers entered a rebuild, batting .273 in 119 games, with 15 home runs (his lowest totals for Texas). In November, at age 39, he announced, “After careful consideration and many sleepless nights, I have made the decision to retire from what I’ve been doing my whole life, which is playing baseball, the game I love.”60

Over 21 seasons, Beltré batted .286. As of 2022, his 1,707 RBIs and 3,166 hits remain major-league records for third basemen.61 At that position, only Hall of Famers Mike Schmidt and Eddie Mathews produced more WAR or hit more homers than Beltré’s 477. Brooks Robinson is the lone player to participate in more double plays or appear in more games at the hot corner.

Beltré joined the Rangers after he turned 30 years old and became one of their greatest and most popular players ever.62 Rangers General Manager Jon Daniels said, “Adrian is one of the best people I’ve had the opportunity to work with. He stands out as much off the field as he does on it.”63 In June 2019, the team retired Beltré’s number. Three years later, he was inducted into the Rangers Hall of Fame.

Even outside of baseball, Beltré is adored. In 2018, the Dallas News named him a finalist for Texan of the Year64 and the Fort Worth Zoo named a baby giraffe ‘Beltré.’65 Madison Kocian, a 2016 Olympic gold medalist in gymnastics, was born the same year that Beltré made his big-league debut. She spoke for many of her fellow native Texans when she commented, “Beltré is probably my number one because I’m a huge Rangers fan, so he’s always been an inspiration for me…he’s dealt with a lot of injuries…he’s fought through them, and he’s just a team player overall, so I’ve looked up to him for a long time.”66

Beltré married Sandra Pérez in 2003 and the couple has three children: Cassandra, Adrian Jr, and Camila. Adrian Jr. was getting attention67 as a professional prospect in 2021 when he was 15, the same age his dad was when he first signed with the Dodgers.

Although he moved his family to Pasadena, California, Beltré’s pride remained with his homeland. He played for the Dominican Republic in the first World Baseball Classic in 2006 and made the all-tournament team.68 In 2017, he represented his country in the WBC again. In 2021, Beltré went back to the baseball stadium where he used to play at Hogar Escuela Santo Domingo Savio. He provided the financial resources for its reconstruction. In his dedication speech, Beltré said in Spanish, “This is a special place for me. I hope the children enjoy it, that they take care of it because I want this to be the place where you see your future and have an idea of where you can go…”69

After watching the newborn that he once held grow into a superstar, Felipe Alou said, “This is a man that should be an example. We are a very small country where everybody knows everybody. Everybody knows the kind of man and player he is. Serious about his trade, his profession.”70 While Beltré’s path to Cooperstown wasn’t as obvious as it might seem, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on the first ballot in 2024. He’s revered as much for his on-field performance as his enormous heart and delightful quirks.

Last revised: January 23, 2024

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Henry Kirn.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Shrpsports.com.

Adrian Beltré’s Dominican League statistics from https://stats.winterballdata.com/players?key=341 (Subscription service. Last accessed June 29, 2022).

Notes

1 Ian Crouch, “Why Adrian Beltré, A Great Baseball Weirdo, Was My Favorite Player,” The New Yorker, November 20, 2018.

2 Matt Johnson, “MLB players react to Adrian Beltré’s retirement,” Sportsnaut, https://sportsnaut.com/mlb-players-react-to-Adrian-Beltrés-retirement/, November 20, 2018.

3 Johnson, “MLB players react to Adrian Beltré’s retirement.”

4 Gerry Fraley, “Flashback: From holding him as a baby to watching him chase 3,000, Felipe Alou knows Adrian Beltré,” Dallas Morning News, November 20, 2018.

5Joe Posnanski, “The Baseball 100: No. 52, Adrian Beltré,” The Athletic, February 4, 2020.

6 Rafael Hermoso, “Beltré’s All-Around Ability Finally Comes to Light,” USA Today (McLean, Virginia), August 31, 2004: C6. Marc J. Spears, “Beltré is Sight for Sore Eyes,” Daily News (Los Angeles, California), June 25, 1998: S10. The latter source says that Beltré’s father had been a minor-leaguer in the St. Louis Cardinals organization, while the former identifies him as a former third baseman/outfielder for the Dominican League’s Leones del Escogido. However, there is no statistical evidence that Bienvenido Beltré appeared in any official games.

7 Rebecca Lopez, “Adrian Beltré, 1st Dominican-born player to record 3,000 hits, reflects on baseball beginnings,” KHOU, July 20, 2017.

8 Fraley, “Flashback: From holding him as a baby to watching him chase 3,000, Felipe Alou knows Adrian Beltré.”

9 Lopez, “Adrian Beltré, 1st Dominican-born player to record 3,000 hits, reflects on baseball beginnings.”

10 Ramón Rodríguez, “De El Café de Herrera Salió Beltré,” Listín Diario (Dominican Republic), August 2, 2017, https://listindiario.com/el-deporte/2017/08/02/476549/de-el-cafe-de-herrera-salio-Beltré (last accessed July 2, 2022).

11 Mike Berardino, “Can’t Dodge Destiny,” Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), March 5, 1999: 9C.

12 Rodríguez, “De El Café de Herrera Salió Beltré.”

13Jonah Keri, “The Often Under-Appreciated Adrian Beltré,” Grantland, https://grantland.com/the-triangle/the-often-underappreciated-Adrian-Beltré/, September 4, 2013.

14 Fraley, “Flashback: From holding him as a baby to watching him chase 3,000, Felipe Alou knows Adrian Beltré.”

15 John Sickels, “Adrian Beltré Prospect Retro,” SB Nation, July 9, 2005, https://www.minorleagueball.com/platform/amp/2005/7/9/23459/18509 (last accessed July 2, 2022).

16 Marla Rivera, “Adrian Beltré on his transition to the big leagues,” ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/19707372/rangers-star-Adrian-Beltré-english-lessons-latino-fans-pickles, June 23, 2017.

17 Adrian Beltré Stats & Scouting Report, Baseball America, https://www.baseballamerica.com/players/12719/Adrian-Beltré/

18 Adrian Beltré Stats & Scouting Report, Baseball America.

19 “1998 Baseball America MLB Prospect Rankings,” Baseball Cube, https://www.thebaseballcube.com/content/prospects_mlb/1998~BA/ (last accessed July 2, 2022). The only players ahead of Beltré were Athletics outfielder Ben Grieve and Paul Konerko, a Dodgers’ prospect who moved from third to first base in 1998.

20 Matt McHale, “Dodgers Bruised by Sheffield Incident,” Santa Cruz Sentinel (Santa Cruz, California), June 30, 1998: 14.

21 Chris Foster and Jason Reid, “Beltré Contributes Immediately,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1998: 10. 0

22 Lopez, “Adrian Beltré, 1st Dominican-born player to record 3,000 hits, reflects on baseball beginnings.”

23 Murray Chass, “Mets Take a Big Step Back to the Future,” The New York Times, November 12, 1998.

24 Murray Chass, “Dodgers Get to Keep Beltré, but Are Penalized,” The New York Times, December 22, 1999.

25 Adrian Beltré’s Dominican League statistics are from https://stats.winterballdata.com/players?key=341 (Subscription service. Last accessed July 3, 2022).

26 John Nadel, “Healthy Beltré Is Grateful,” AP News, March 2, 2002.

27 Andy McCullough, “To Dodgers, Adrian Beltré is the Hall of Famer who got away,” Los Angeles Times, June 12, 2018.

28 Posnanski, “The Baseball 100: No. 52, Adrian Beltré.”

29 Bruce Bolch, “Early Returns for Beltré Are Encouraging,” Los Angeles Times, April 12, 2004.

30 Bill Plaschke, “Beltré didn’t want to leave LA,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 2005.

31 Plaschke, “Beltré didn’t want to leave LA.”

32 Matt Borelli, “Rangers’ Adrian Beltré Reveals He Wanted To Remain With Dodgers Organization ‘forever’,” Dodger Blue, https://dodgerblue.com/rangers-Adrian-Beltré-wanted-remain-dodgers-organization-entire-career/2018/06/13/, June 13, 2018.

33 Shaikin, “Beltré Looks Right at Home,” Los Angeles Times, June 21, 2006.

34 Shaikin, “Beltré Looks Right at Home.”

35 Bill Shaikin, “Beltré Looks Right at Home.”

36 Between 1998-2007, Beltré had the second highest dWAR (11.2) amongst third basemen and the 10th highest all players at any position.

37 Ryan Hudson, “Despite Grapefruit-Sized Testicle, Beltré Still Does Not Wear a Cup,” SBNATION, https://www.sbnation.com/2010/3/3/1335540/Adrian-Beltré-testicle-cup-red-sox, March 3, 2010.

38 Hudson, “Despite Grapefruit-Sized Testicle, Beltré Still Does Not Wear a Cup.”

39 Adrian Beltré, Baseball-Reference Bullpen.

40 Tyler Kepner, “Rangers’ Adrian Beltré Plays Third Base Like No One Else,” New York Times, August 31, 2012.

41 Efrain Ruiz Pantin, “The Joy of Adrian Beltré,” La Vida Baseball, November 20, 2018

42 Whitney McIntosh, “Felix Hernandez congratulated Adrian Beltré on 3,000 hits in the middle of an inning,” SBNATION, https://www.sbnation.com/mlb/2017/7/31/16073928/felix-hernandez-congratulates-Adrian-Beltré-middle-of-inning-hugz-on-hugz (last accessed August 10, 2022)

43 “Red Sox reach deal with Beltré,” ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/boston/mlb/news/story?id=4795915 (last accessed August 10, 2022).

44 Richard Durrett, “Free Agent Adrian Beltré, Texas Rangers agree to 6-year deal,” ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/dallas/mlb/news/story?id=5991829, January 5, 2011.

45 Joe Christensen, “The Top of His Game; The Best Third Baseman in Baseball?” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), July 24, 2011: C7.

46 Adrian Beltré, 2018 Topps Tribute baseball card.

47Joshua Carney, “Reliving Memorable Rangers Moments: Adrian Beltré Goes Yard From One Knee in in 2011 World Series,” Fan Nation, https://www.si.com/mlb/rangers/news/rangers-Adrian-Beltré-home-run-one-knee-2011-world-series, March 24, 2020.

48 Gerry Fraley, “Adrian Beltré ‘still trying to get over’ World Series,” Dallas Morning News, January 12, 2012.

49 “2012 MLB All-Star Game: Adrian Beltré’s Biggest Fear,” Youtube, uploaded by Secret Base, July 10, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YurfBBLq-IE.

50 Crouch, “Why Adrian Beltré, A Great Baseball Weirdo, Was My Favorite Player.”

51 Stephanie Apstein, “Future Hall of Famer is missing one thing: a ring,” Sports Illustrated, March 29.2016.

52 Rodger Sherman, “Adrian Beltré throws glove at ball, has had just about enough of Carlos Gonzalez,” SBNATION, https://www.sbnation.com/lookit/2014/5/6/5689778/Adrian-Beltré-throws-glove-at-ball-has-had-just-about-enough-of, May 6, 2014.

53 Evan Grant, “Adrian Beltré on Miguel Cabrera’s head pat: ‘I can’t say anything about the best hitter in the league,’” The Dallas Morning News, May 24, 2014.

54 Sam Butler, “Adrian Beltré was asked to go back to the on-deck circle, so he dragged it to where he was instead,” Cut 4, https://www.mlb.com/cut4/Adrian-Beltré-moved-the-on-deck-circle-to-where-he-wanted-it-to-be-and-was-eject, July 27, 2017.

55 Eddie Mathews, Mike Schmidt, Darrell Evans, and Chipper Jones are the others.

56 “Adrian Beltré of Texas Rangers hits 400th career HR,” ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/dallas/mlb/story/_/id/12895412/Adrian-Beltré-texas-rangers-hits-400th-career-hr, May 15, 2015.

57 John Reilly, Bob Meusel, and Babe Herman were the others. Trea Turner and Christian Yelich have since joined them.

58 T.R. Sullivan, “Beltré joins elite club with third cycle,” MLB.com, https://www.mlb.com/news/Adrian-Beltré-hits-for-cycle-for-third-time-c140986632, August 3, 2015.

59 Joseph Myers, “Copyrights to Keep Three MLB Participants From Using Preferred Nicknames During Players Weekend,” Promo Marketing Magazine, August 24, 2017, https://magazine.promomarketing.com/article/copyrights-keep-three-mlb-participants-using-preferred-nicknames-players-weekend/ (last accessed July 3, 2022).

60 “Statement from Adrian Beltré,” MLB.com, https://www.mlb.com/press-release/statement-from-Adrian-Beltré-300952152, November 20. 2018.

61 For players who played at least 30% of their games at third base.

62 Chris Halicke, “Texas Rangers All-Time Team: Position Players,” Fan Nation, https://www.si.com/mlb/rangers/news/texas-rangers-all-time-team-position-players, April 24, 2020.

63 T.R. Sullivan, “Beltré steps away after legendary career,” MLB.com, https://www.mlb.com/news/Adrian-Beltré-announces-retirement-c300949902, November 20, 2018.

64 Dallas Morning News Editorial. “Texas of the Year finalist Adrian Beltré brought a love of baseball to Texas Rangers fans,” Dallas Morning News, December 23, 2018.

65 Patrick Basler, “Fort Worth Zoo names baby giraffe Beltré and baseball got a lot cuter,” SBNATION, https://www.sbnation.com/lookit/2017/7/31/16069586/fort-worth-zoo-baby-giraffe-name-Adrian-Beltré-3000-hits, July 31, 2017.

66 “Texas of the Year finalist Adrian Beltré brought a love of baseball to Texas Rangers fans.”

67 Tyler Henderson, “Baby Beltré fits nicely into the Texas Rangers’ long term plans,” Nolan Writin’, January 7, 2022.

68 “2017 WBS MVP and All-Tournament Team Announced,” MLB.com, March 23, 2017, https://www.mlb.com/press-release/2017-wbc-mvp-and-all-tournament-team-announced-220520420 (last accessed July 3, 2022).

69 “Adrian Beltré inaugurates the remodeling of the Domingo Savio home school,” El Nuevo Diario (República Dominicana), December 6, 2021.

70 Fraley, “Flashback: From holding him as a baby to watching him chase 3,000, Felipe Alou knows Adrian Beltré.”

Full Name

Adrian Beltré Pérez

Born

April 7, 1979 at Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.