Bump Wills

Growing up in the shadow of his father – a Los Angeles Dodgers star and the 1962 National League MVP – could be a challenge for Bump Wills. Often referred to as the “son of Maury Wills,” Bump did not let that sway his focus and competitiveness. He spent six seasons (1977-1982) of his own in the majors with the Texas Rangers and Chicago Cubs. The switch-hitter finished third in American League Rookie of the Year voting in 1977, topped the circuit’s second basemen in assists twice, and set a Rangers single-season record for stolen bases that still stands as of 2021.

Growing up in the shadow of his father – a Los Angeles Dodgers star and the 1962 National League MVP – could be a challenge for Bump Wills. Often referred to as the “son of Maury Wills,” Bump did not let that sway his focus and competitiveness. He spent six seasons (1977-1982) of his own in the majors with the Texas Rangers and Chicago Cubs. The switch-hitter finished third in American League Rookie of the Year voting in 1977, topped the circuit’s second basemen in assists twice, and set a Rangers single-season record for stolen bases that still stands as of 2021.

It’s fair to ask how somebody born Elliott Taylor Wills on July 27, 1952, in Washington D.C., came to be nicknamed Bump. “My dad admired [former University of Michigan halfback] Bump Elliott,” Wills explained. “So, when I was born, I was given my first name and my nickname after him. But really, I guess part of the reason for Elliott is that it’s my mother’s maiden name. She’s Gertrude Elliott.”1 Gertrude, however, told a different story. Not only was Bump active as a kid; he was ready to start fielding ground balls before birth, often kicking and active in her womb during her pregnancy. That’s where the nickname “Bumpy” was derived. Later as an aspiring professional ballplayer, Bump dropped the “y” because he felt it was a more mature and stronger name.2

Bump had one older brother and four sisters, three of whom were younger.3 They lived in downtown Spokane, Washington when their father played Triple-A baseball there. When Maury Wills was promoted to the majors in the summer of 1959, the rest of the family stayed behind and settled in Spokane Valley, a predominantly white, affluent city. Since the Wills were one of the community’s few African-American families, that presented challenges, but Bump never allowed them to become obstacles.4

During summers from fifth grade through high school, Bump often visited Los Angeles while his father was playing for the Dodgers. Shagging balls hit by Duke Snider or Gil Hodges during batting practice, and sitting in the dugout watching Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale pitch exposed Bump to the major-league environment, thus planting the seeds for his future in professional baseball.5

Bump was a three-year letterman in baseball, football, and basketball for the Central Valley High School Bears in Spokane. Whether Wills was fielding ground balls at shortstop, playing halfback on the gridiron, or playing guard on the hardwood, his brother Barry was his inspiration, driving his competitiveness and will to do his job. Between them, the brothers had a code, “Ask no quarter, give no quarter.” In other words, give no slack and play as hard as you can. “Every year we used to watch the 1960s film The Alamo, and as the soldiers never gave up defending the mission, we never quit, and our competitive spirit was influenced by this dedication,” Wills recalled. Since Barry was two years older, Bump was often the smaller, less accomplished sibling during pickup basketball with his brother and his brother’s friends. The experience drove him to develop focus.6

Central Valley won the Washington State’s 4A basketball title during Barry’s senior season and Bump – then a sophomore – recalled that “it was like magic” seeing them practice. “Between watching the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Central Valley varsity basketball team, this is where I learned the sense on how to win and what it took to be successful,” he said. “Barry made a significant contribution to my ability to achieve my goal of making it to the major leagues.”7

Following his 1970 graduation, Wills received a baseball scholarship to attend Arizona State University (ASU). “Dad was glad I took it because he never had the opportunity to go to college,” he said.8 Wills studied Mass Communications. As a freshman in 1971, he appeared in only three games under manager Bobby Winkles.

After his freshman year, Wills spent the first of three summers with the Anchorage Glacier Pilots of the Alaska Baseball League (ABL). The Glacier Pilots won the championship in 1971. Half a century later, Wills still remains in touch with the Brown family, who hosted him in Anchorage. During his three-year ABL career, Wills set a league record for at-bats.9

As an ASU sophomore, Wills played left field for the first time in his life. and learned to switch-hit. “I feel very confident batting lefthanded,” he remarked three years later (his career major league splits were almost identical.10 Under first-year coach Jim Brock, the Sun Devils went 64-6 in 1972 – including a string of 32 straight wins. Wills earned All-NCAA District 7 and All-Western Athletic Conference honors by batting .355 with 24 stolen bases and a 25-game hitting streak.11 Although Wills made the All-College World Series team, ASU fell to the University of Southern California in the finals. “It was a heartbreaking loss,” he stated.12

In 1973, Wills shifted to shortstop and hit .289 with 15 steals to help ASU return to the CWS finals, where they lost to USC again.13 Wills was moved to second base as a senior in 1974 and batted .383 with 25 steals. After producing a total of six home runs in 126 games the previous two years, he went deep eight times in 45 contests– with three of the blasts coming in a single game.14

Wills’ performance raised the eyebrows of big-league scouts but, two weeks before the June 1974 amateur draft, he was injured during first-to-third baserunning drills after a late-season loss. “As I made the turn at second, Brock was waving me to third and as I approached the base, he directed me to the outfield side of the base, but then change[d] with a sweeping motion to the inside of the base,” Wills explained. “I tried to adjust my slide and broke my leg.”15 In 1976, the incident was portrayed in the motion picture and book The Devil’s Coach, as the event that spurred Coach Brock’s rebirth into Christianity. In the movie, Wills was played by future major leaguer Rick Peters.16

At the hospital, doctors told Wills that he might never run like he had prior to his injury, and he wondered about his baseball future. “It was at this time that I decided that while this was a temporary setback, I was going to play major-league baseball,” he recalled.17 The San Diego Padres drafted him in the 12th round, but he did not sign. After Wills recuperated from ankle surgery, he played winter ball for the Mexican Pacific League’s Naranjeros de Hermosillo, a club that was managed by his father for part of the campaign.18 Although he batted just .244, Wills appeared in 71 games and accompanied the circuit champion Naranjeros to Puerto Rico for the Caribbean Series. By then, he’d been drafted again, by the Texas Rangers with the sixth overall pick in January 1975.

Wills was late reporting to spring training as his father – serving as his agent – negotiated for a higher signing bonus. When Wills finally signed, he arrived in the Rangers clubhouse in Pompano Beach, Florida, and found that the jersey in his locker did not have a name or number. Nonetheless, he scurried about to get dressed and hustled out on the field as the team was already stretching in left field. Rangers manager Billy Martin noticed and shouted, “[Clubhouse manager Joe] Macko! Get a name and number on this jersey or you are out of here!” Wills had a fully stitched jersey by his second day on the diamond.19

In 1975, Wills debuted with the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Rangers in the Double-A Eastern League. He remained so focused on his day-to-day responsibilities that he didn’t understand why the opposing catcher “wished him luck” prior to the season finale. Wills was contending for a batting title and finished at .307 in 122 games after a 1-for-4 day, good for third in the circuit behind West Haven teammates Dave Bergman (who took the day off) and Dell Alston, who batted .311 and .308, respectively. After a midseason move from shortstop to second base, where he felt more comfortable, Wills was named the utilityman on the Eastern League All-Star team.20 “It was a Cinderella year for me,” he said. “I was in love with my future wife and the game of baseball.”21 (He married Laverne Capilla in 1977 and the couple had a daughter, Mauricia, before divorcing.)

That winter, Wills returned to Hermosillo and hit .253 in 79 contests to help the Naranjeros repeat as Mexican Pacific League champions. The team also prevailed at the Caribbean Series in the Dominican Republic, with Wills making the tournament All-Star team.

The Rangers promoted Wills to the Sacramento Solons of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in 1976. In May, he was sidelined by a hairline fracture of his right thumb. Then he missed more time after trying to come back too soon.22 Despite being limited to 117 games, the 5-foot-9, 172-pound Wills batted .324 with 26 home runs – just two behind Bob Gorinski for the PCL lead. With the draft to stock the rosters of the new Toronto Blue Jays and Seattle Mariners franchises approaching that fall, the Rangers opted to keep Wills in Triple-A rather than promote him in September and be forced to reserve him. That was not a bad thing, according to Maury Wills, who said, “Bump will hit major league pitching, but while the Rangers are protecting him against the expansion draft, he’ll have a better chance to correct his flaws while playing in the minors.”23

“Bump is a major league player, I have no doubt about that, but I just hate to see all that extra pressure that has been put on his back by the publicity buildup the last two years,” said Sacramento skipper Rich Donnelly. “Bump is no super star, but I think he can be a good every day second baseman as a rookie. You just can’t expect too much too soon. He can make the major league plays with the glove and he can turn the double play, but he’s going to have to be given time to learn and develop in the majors.”24

In 65 winter-ball contests with the Naranjeros, Wills hit .329 and led the Mexican Pacific League with 48 runs scored.25 Heading into 1977 spring training, Rangers manager Frank Lucchesi planned for Wills and another ASU alum, veteran Lenny Randle, to compete for Texas’s second base job.26 When the March 28 issue of Sports Illustrated hit newsstands, though, it featured a photo of Wills in the infield next to the sub coverline “Maury Wills’ Son Bump Makes the Majors.”27 Randle attempted to speak with Lucchesi about playing time prior to an exhibition against the Twins in Orlando, but the skipper wanted to talk later because he was watching batting practice with his coaches.

After another unsuccessful attempt to start the conversation, Randle blindsided Lucchesi with a punch to the head, knocking the skipper down. Randle delivered more blows while Lucchesi was on the ground before anyone could process what was happening. Wills witnessed the incident from a short distance away.28 Randle wound up being traded to the Mets. After Lucchesi was fired in June, he blamed Randle’s insurrection for his termination. In December 1978, the manager’s lawsuit against his former player was settled amicably out of court.29

During Wills’ rookie season – a time when a player needed consistency and leadership from his manager – he played for four different skippers. Coach Eddie Stanky led the team for one game and Connie Ryan for six before Orioles coach Billy Hunter was hired to take over the Rangers in June. Nevertheless, Wills said, “My first year in the major leagues was magical,” recalling that he was “in the zone” coming off two strong seasons in the minors.30

On April 7, 1977, Wills debuted on Opening Day at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore. Future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer pitched for the Orioles, and Rangers third baseman Toby Harrah warned Wills, “Palmer likes to throw his rising fastball. This pitch is going to look good, but if you don’t get on top of it, you will fly out.” It was good advice. After drawing a first inning walk, Wills made outs in the air in each of his next two trips before grounding out in his third at-bat. With the score tied, 1-1, with two outs and a runner on third in the top of the 10th, however, Wills lined Palmer’s 2-and-1 fastball up the middle for what proved to be the game-winning hit. He learned later that Lucchesi had considered sending veteran John Ellis up to pinch-hit for him.31

Prior to a May 3 contest in Detroit, Wills was batting just .215 and beginning to doubt his ability to hit big-league pitching. He’d spoken to his father only a few times because of the elder Wills’ broadcasting work but, that day, they had a long talk about peaks and valleys and the mental aspects of performing in the majors. Bump went 4-for-5 that night, including his first homer in the majors.32 He went on to hit .392 in the month of May, raising his overall average to .317. That summer, the rookie acknowledged the unique pressures of having a famous father. “The fact my name is Wills has its advantages and disadvantages. Certainly, it has opened some doors for me in baseball. I know it helped me get a scholarship to Arizona State. But the disadvantage is the comparisons that are always going to be made between my father and me. Not only comparisons, but expectations, too.”33

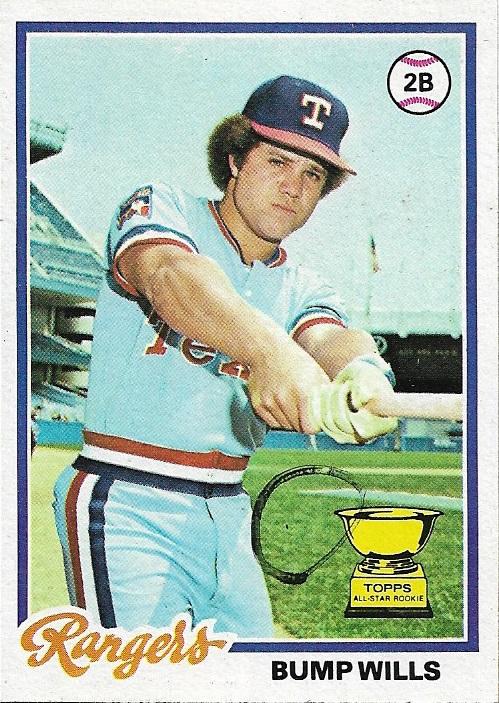

Wills formed a solid double-play combination with shortstop Bert Campaneris, a veteran who’d played for three straight World Series champion Oakland A’s teams from 1972 to 1974. After Hunter became the manager, the Rangers surged into first place briefly in mid-August before finishing eight games behind the 102-win Royals with a 94-68 record, the best in franchise history at the time.34 In 152 games, Wills batted .287 with 87 runs scored and 28 steals. He led American League second baseman with 492 assists and was rated the circuit’s eighth-best defender by the modern Defensive WAR metric.35 Topps named Wills to its all-rookie team, and he received four first-place votes in AL Rookie of the Year balloting to finish third behind future Hall of Famer Eddie Murray of the Orioles and Oakland’s Mitchell Page. “I thought some people in the Texas organization may have overrated [Wills],” Hunter confessed. “You know, because of his name and everything. But now I know that wasn’t the case. He had a lot to live up to, but he’s done it.”36

Although Wills had grown up around major-league players, his first hit to left field against the Red Sox was a big deal to him. “That was fielded by Yaz [Carl Yastrzemski], YAZ!” he expressed emphatically. Wills’ favorite player, though, was his teammate Harrah, whom he admired so much that he named his dog after him.37 On August 27, 1977, at Yankee Stadium, Harrah and Wills made history by hitting back-to-back inside-the-park homers off New York’s Ken Clay. While that had happened one previous time in major-league history, Harrah and Wills may have been the first to do it on consecutive pitches.38

In 1978, the Rangers finished second behind the Royals again, and Wills led all major-league second baseman in assists. He hit just .225 before the All-Star break, however, but raised his overall average to .250 with a strong second half. With 52 stolen bases, he ranked third in the circuit and established a club record.

Under new manager Pat Corrales, the Rangers were briefly atop the AL West in July 1979 before finishing in third place with an 83-79 record following a dismal second half. Wills was a bright spot, batting .273 in 146 games with a club-high 90 runs scored and 35 steals. Since reaching the majors, he’d continued to play winter ball for Hermosillo, hitting .266 in 34 contests after his rookie campaign and .336 in 37 appearances after his second year. In the winter of 1979-80, Wills played his final year for the Naranjeros. In 28 games, he batted .280 and the club won its third Mexican Pacific League title in his six seasons.

In 1980, Wills led Texas in both runs scored (102) and stolen bases (34) again while stroking 31 doubles – a personal best – and batting .263. He also turned a career-high 112 double plays and posted his best fielding percentage, .984. On September 25 in Seattle, Wills singled to lead off a game against the Mariners – who’d named his father their manager in August. It marked the first time in major-league history that a son had played against a team skippered by his father. He hit .444 (8-for-18) in six contests against his father’s Mariners, four of which were won by Texas. Despite Bump’s solid season, the Rangers finished nine games under .500 and in fourth place.

The Rangers rebounded to finish with the AL West’s second-best overall record in 1981 but failed to win either half of the split season that was caused by a lengthy players’ strike. Wills struggled to get into a groove and batted .251 in 102 games, with career lows in on-base percentage (.304) and slugging (.307). He was aware that, “the Rangers would not sign players coming into their free agent year and would look to trade players before their sixth season.”39 Adding to his uneasiness, as Wills approached his sixth season of 1982, Texas traded reliever Jim Kern to the New York Mets at the December 1981 winter meetings for journeyman pitcher Dan Boitano and former Gold Glove second baseman Doug Flynn. The Sporting News later reported that Wills was nearly dealt to the St. Louis Cardinals or Oakland A’s around the same time.40

When spring training started in 1982, Wills was still with the Rangers. Despite losing the arbitration case in which he’d sought a $450,000 salary, the $355,000 that Wills was awarded was still a significant raise from the $275,000 he’d earned the previous year.41 Texas GM Eddie Robinson told reporters that Wills and his agent, Dick Moss, had made it clear that they wanted a multi-year deal or a trade, however.42 With Flynn and top prospect Mike Richardt receiving most of the playing time, Wills had only four exhibition at-bats before the Rangers trainer told him that “Zim” wanted to see him in his office on March 26. “Zim” was Don Zimmer, the Rangers new manager and a former Dodgers teammate of Maury Wills. Looking emotional, Zimmer told Bump that he’d been traded to the Chicago Cubs and that he felt bad for how he’d been treated by management. In return, Texas received lefty Paul Mirabella, cash, and a player to be named later (minor-league pitcher Paul Semall). The next morning, Wills drove from Florida to Phoenix, Arizona to meet up with his new team. The season was less than two weeks away.43

On April 5, Opening Day in Cincinnati, Wills led off against Reds’ fastballer Mario Soto and worked the count to 3-and-1. “I anticipated that Soto would throw his dependable pitch, I hit a laser to the outfield for a home run,” Wills recalled. “It was what I do.” In their next meeting, Soto evened the battle by whiffing Wills with a 3-2 changeup, getting him off balance and out in front. Wills nodded his head to give credit for a good pitch but felt frustrated when Soto responded with an arrogant smirk. In frustration, Wills proceeded to skip his helmet in the pitcher’s direction.44 Wills later singled against reliever Bob Shirley to finish the contest 2-for-4, and the Cubs got the last laugh by beating Soto, 3-2.

From day one with the Cubs, Wills felt like manager Lee Elia did not like him, so he expected his time with the team to be short.45 Wills batted .272 in 128 games and led Chicago with 35 steals, but he lost playing time to light-hitting Junior Kennedy in July and August. Then in September, the Cubs moved rookie third baseman Ryne Sandberg to second base. “I have to see who can play in case Bump doesn’t come back,” Elia explained. Wills’ agent had made it clear that his client intended to leave as a free agent if the Cubs didn’t sign him to a multi-year deal. “It looks like they’re going with the young players. That’s fine, except I’m not exactly old,” said Wills, who turned 30 that summer.46

After becoming a free agent, Wills had an opportunity to sign with the New York Yankees. But owner George Steinbrenner was causing instability with veterans such as Dave Winfield and Steve Kemp, so Wills decided that he did not want to play in the Bronx. His agent negotiated a four-year deal with the Hankyu Braves of the Japan Pacific League.47

Japan was a positive experience for Wills away from the baseball diamond, but life on the field was not what he expected. Japanese baseball tradition placed more importance on preparation than actual game play. Thus, Wills spent countless hours practicing. The style of play was not what he was accustomed to in the United States, and balancing baseball and family became challenging to the point where it made him consistently ill. After batting .272 in 125 games in 1983, Wills was hitting .232 in 78 contests in 1984 when he was bought out of his contract and headed home. As the plane lifted off the tarmac from Osaka to head to the United States, he recalled that, miraculously, “the stress and sickness went away.”48

Wills took a few years off from baseball and never played professionally again. He finished his six-year major-league career with a .266 batting average and 196 stolen bases in 831 games.

Wills’ 1979 Topps baseball card remains a fan favorite for avid collectors of that generation. False rumors that an imminent trade sending Wills to the Blue Jays was a done deal were relayed to Sy Berger, President of Topps Chewing Gum. So, Topps changed the team name on Wills’ card to “Blue Jays,” which became available to the public in wax packs for a limited time before the mistake was corrected in later productions.49 Although Wills never really collected memorabilia, he has various photos and paintings on the wall of his den from his and his father’s playing days, and was quick to point out in an interview with the author that he has the “Bump Wills error card” that is still talked about in collector’s lore.50

When Wills was still with the Rangers, he was vacuuming his apartment one day and thinking about what it took to be a professional ballplayer. “Play hard and play focused,” was his philosophy. “By playing mistake-free baseball, we do not beat ourselves.”51 He developed his list of “Nine Intangibles” that day – traits every ballplayer must have to reach the ultimate goal of playing in the majors:

- Self Confidence

- Positive (Self Talk)

- Strong Work Ethic

- Ability to Focus

- Become Unselfish

- Competitiveness

- Durability, Toughness (Dealing with setbacks and pain)

- Be a Good Teammate (Respect on and off the field)

- Passion for the Game

Wills returned to professional baseball from 1988 to 1990 as the manager of the Rangers’ Butte (Montana) Copper Kings affiliate in the rookie-level Pioneer League. The club won the South Division in each of his first two seasons. In 1991, he led the Gastonia (North Carolina) Rangers in the Class A South Atlantic League, followed by a season at the helm of the Port Charlotte Rangers of the Class A Florida State League in 1992. Wills continued to coach through 1997 as an infield and baserunning instructor. He also managed the Hudson Valley (New York) Renegades of the Class A New York-Penn League in 1995 and 1996. In 2004, he spent spring training with the Florida Marlins as an infield instructor.52

By then, Wills had divorced Laverne Capilla and married Marla Boland, with whom he fathered two more daughters, Meagan and Madeline, before divorcing again. Regarding baseball, instead of working with professionals, he turned his passion for the sport towards helping youth players through coaching and instructional clinics.

As of 2021, Wills and his wife Deborah Shriver (they were married in 2015) reside in Garland, Texas. He is a coach for the Dallas Mustangs, a select baseball organization in which he focuses on helping high school athletes who aspire to play college or professional baseball. He also assists the Hillcrest High School baseball team each spring.53

Last revised: December 18, 2022 (zp)

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Bump Wills (personal interviews with Gary Packan at Wills’ home in Garland, Texas; December 29, 2020, and January 18, 2021).

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Bump Wills’ Mexican Pacific League statistics are from page 647 of Guillermo Gastélum Duarte’s Enciclopedia Conmemorativa del 75 Aniversario del le Liga Meixcana del Pacifico, (2019, Moby Dick Editorial: Culiacán, Mexico).

Notes

1 Roger O’Gara, “Bump Wills Sees Good and Bad in Being Son of Famous Dad,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1975: 39.

2 Bump Wills, personal interviews with Gary Packan on December 29, 2020, and January 18, 2021 (Hereafter Wills-Packan interview.

3 O’Gara, “Bump Wills Sees Good and Bad in Being Son of Famous Dad.”

4 Wills-Packan interview.

5 Wills-Packan interview.

6 Wills-Packan interview.

7 Wills-Packan interview.

8 O’Gara, “Bump Wills Sees Good and Bad in Being Son of Famous Dad.”

9 Wills-Packan interview.

10 O’Gara, “Bump Wills Sees Good and Bad in Being Son of Famous Dad.”

11 Bump Wills, 1990-91 Collegiate Collection baseball card.

12 Wills-Packan interview.

13 Wills, 1990-91 Collegiate Collection.

14 Bump Wills, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, April 22, 1976.

15 Wills-Packan interview.

16 Brock, Jim and Gilmartin, Joe. The Devil’s Coach, (Elgin: David C. Cook Publishing Co., 1977).

17 Wills-Packan interview.

18 O’Gara, “Bump Wills Sees Good and Bad in Being Son of Famous Dad.”

19 Wills-Packan interview.

20 “Quebec City’s Roenicke Picked as Eastern MVP,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1975: 33.

21 Wills-Packan interview.

22 “Wills Hurt Again,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1976: 50.

23 “Bump Wills Makes Music with Solid Bat and Guitar,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1976: 31.

24 Randy Galloway, “Can Campy Plug the Rangers’ Leaky Defense?” The Sporting News, January 29, 1977: 38.

25 Guillermo Gastélum Duarte, Enciclopedia Conmemorativa del 75 Aniversario del le Liga Meixcana del Pacifico, (2019, Moby Dick Editorial: Culiacán, Mexico): 44.

26 Bruce Markusen, “Card Corner Plus: The Redemption of Lenny Randle,” Hardball Times, January 26, 2015, https://tht.fangraphs.com/card-corner-plus-the-redemption-of-lenny-randle/ (last accessed October 17, 2021).

27 Peter Gammons, “Bumper Crop of Boys from the Farm,” Sports Illustrated, March 28, 1977: 24-26.

28 Wills-Packan interview.

29 Associated Press, “Suit by Lucchesi Ends Amicably,” New York Times, December 9, 1978: 20.

30 Wills-Packan interview.

31 Wills-Packan interview.

32 Randy Galloway, “Rookie Bump Smoothing Rangers’ Title Path,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1977: 3. 17.

33 Galloway, “Rookie Bump Smoothing Rangers’ Title Path.”

34 The 1999 Texas Rangers went 95-67. As of 2021, the team’s 96-66 record in 2011 is the new standard.

35 Defensive WAR (Wins Above Replacement) measures a player’s defensive statistics compared to the league average with a position adjustment. Based on Baseball Info Solutions’ Defensive Runs Saved and the Total Zone Rating developed by Baseball Projection’s Sean Smith.

36 Galloway, “Rookie Bump Smoothing Rangers’ Title Path.”

37 Wills-Packan interview.

38 The Cubs Marv Rickert and Eddie Waitkus hit consecutive inside-the-park homers in 1946, but it’s not known whether they were hit on successive pitches. Murray Chass, “2 Are Inside the Park, on Successive Pitches,” New York Times, August 28, 1977: 162.

39 Wills-Packan interview.

40 Jim Reeves, “Wills is Fearful He’ll be Sitting,” The Sporting News, March 27,1982: 39.

41 Randy Galloway, “$50,000 Bonuses Cause Grumbling,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1982: 37.

42 Reeves, “Wills is Fearful He’ll be Sitting.”

43 Wills-Packan interview.

44 Wills-Packan interview.

45 Wills-Packan interview.

46 Joe Goddard, “Cubs Could Drop Free Agent Wills,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1982: 17.

47 Wills-Packan interview.

48 Wills-Packan interview.

49 Bruce Markusen, “#Card Corner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills,” https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/card-corner/bump-wills-and-blue-jays (last accessed October 17, 2021).

50 Wills-Packan interview.

51 Wills-Packan interview.

52 Wills-Packan interview.

53 Wills-Packan interview.

Full Name

Elliott Taylor Wills

Born

July 27, 1952 at Washington, DC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.