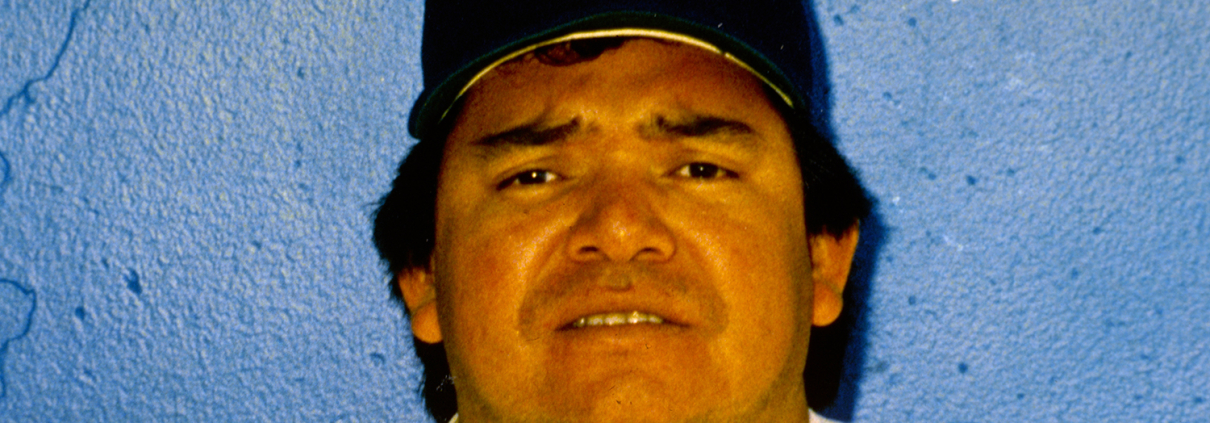

Fernando Valenzuela

Through 2024, over 23,000 players have played baseball in the major leagues; only 152 were born in Mexico. Fernando Valenzuela stands above them all. One of the game’s brightest and most beloved stars over the course of his 17-season MLB pitching career (1980-1991, 1993-1997), Valenzuela’s 173 victories, six All-Star selections, and 41.5 career WAR topped all his countrymen.1

A southpaw with a trademark delivery and superlative screwball, Valenzuela enjoyed his greatest success with the Los Angeles Dodgers, his team from 1980-1990. In his first full season (the 1981 strike season), when he became the only major-leaguer to earn the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards in the same season, he achieved superstardom and sparked “Fernandomania,” a cultural phenomenon that transformed Mexican American and Latino communities and accelerated MLB’s outreach to international players and fans. Smitten with Valenzuela, the fans mostly called him “Fernando” or “El Toro” (the Bull). That season, Valenzuela also started the All-Star Game for the National League and beat the Yankees in Game Three of the World Series, helping the Dodgers overcome a two-games-to-zero deficit and win the 1981 championship. It was the franchise’s first title since 1965, when they were led by another legendary left-handed pitcher, Sandy Koufax.

After his playing career, Valenzuela spent 22 years (2003-2024) as a Spanish-language radio and television voice for the Dodgers, reaching new generations of fans. He also supported the growth of the game across his home country, serving four times on the coaching staff for Mexico during the World Baseball Classic. Valenzuela returned to his Mexican League roots in 2017 when he led an ownership group that purchased the Quintana Roo Tigres, a lifeline that enabled the franchise to stay in its home city and park.

In 2023, the Dodgers club officially retired his uniform number 34. As team president and CEO Stan Kasten put it on that occasion, more than 30 years after Valenzuela last pitched for the Dodgers, “Fernandomania never has ended. It’s still going on today, which is what brings us here tonight.”2 Valenzuela died on October 22, 2024, at age 63, one day before the 43rd anniversary of his World Series victory over the Yankees. On November 1, 2024, on the day that would have been his 64th birthday, the franchise and fans honored Valenzuela during the victory parade and stadium celebration following the Dodgers’ 2024 World Series victory over the Yankees.

Fernando Valenzuela Anguamea’s story is as remarkable as it was improbable. He was born and raised in Etchohuaquila, an impoverished farming village (population under 200) in the state of Sonora, in northwest Mexico (about 20 miles inland from the Gulf of California coast and 335 miles south of Arizona).3 According to Dodgers’ official records, Valenzuela’s birth date was November 1, 1960 (but some questioned whether he was older based on his mature looks and poise).4 The youngest of seven sons; he also had five older sisters. His parents, Avelino and Emergilda, were communal farmers and raised 12 children in a five-room, mud-floor, adobe house without running water. In describing his childhood to the media in 1981, Valenzuela recounted that they were a religious Catholic family, were poor but never lacked for food or clothes, and lived in a large house.5

When the Valenzuela boys were not working as farmhands, they liked to play baseball. Rafael pitched – Francisco, Daniel and Gerardo played infield – Manuel manned the outfield – and Abelino pitched in relief. A village friend was the catcher. Fernando usually played first base, pitching only occasionally because his brothers thought he was too young.6 But Rafael noticed his potential and encouraged him. By age 15, Fernando was more interested in baseball than going to school; he dropped out of high school after one year to play ball.7 Valenzuela revered Mexican players and dreamed of playing professionally in his country – he never seriously thought of playing in the United States. Eventually, Valenzuela caught the eye of local scouts and played for various local Mexico minor league teams.

Cuban-born Dodgers scout Mike Brito was a pioneer in scouting players from Mexico. When Brito was assigned to central Mexico to see a minor league shortstop in the summer of 1979, Valenzuela (then age 18) pitched for the visiting team. Brito began following Valenzuela and his positive reports and enthusiasm led to the Dodgers signing the prospect after a battle of offers with the New York Yankees.8 This chance scouting encounter predated independent baseball academies and trainers that are used by many Latino baseball prospects in contemporary baseball.

After the Dodgers signed Valenzuela, they assigned him to the Lodi Dodgers in the Single-A California League, where he made three appearances. Brito and the Dodgers’ brass believed that Valenzuela needed to learn another pitch to complement his average-velocity fastball. So during the 1979-1980 offseason, Valenzuela learned to throw a screwball from Bobby Castillo, a Dodgers reliever. The screwball is an off-speed pitch that, when thrown by a southpaw, breaks into left-handed batters and away from right-handed batters (the opposite of a curveball). Not many pitchers have mastered the screwball, but Valenzuela’s was generally considered the best since Carl Hubbell’s in the 1930s.9 In another interesting parallel, Valenzuela later joined Hubbell as the only pitchers to strike out five consecutive batters in an All-Star Game.10 The pitch has mostly died out and is rarely utilized in the contemporary game of power pitchers and advanced analytics.11

In 1980, Valenzuela was promoted to the San Antonio Dodgers, L.A.’s Double-A Texas League affiliate. He continued to develop his screwball, started 25 games, compiled a 13-9 record and posted a 3.10 ERA. The Dodgers were watching. At the end of that season, at age 19, Valenzuela earned a call-up straight to the major league club. He pitched 17 innings over 10 relief appearances and yielded zero earned runs.

Heading into the 1981 season, Jerry Reuss and Burt Hooton were L.A.’s front-line starters (the Dodgers had lost Don Sutton to free agency in the offseason). Due to injuries to his preferred pitchers, manager Tom Lasorda tabbed Valenzuela to start on Opening Day at Dodger Stadium, the first rookie so honored in the franchise’s 98-year history.12 Valenzuela rose to the occasion. The Dodgers beat the Houston Astros, 2-0, and he pitched a complete game, striking out the last batter swinging through his screwball. Legendary broadcaster Vin Scully had the call: “What a way to start – Fernando Valenzuela – in his first big league start, pitches a shutout.”13 By May 14 of that first full season, Valenzuela was 8-0 with a 0.50 ERA. He pitched nine innings in eight straight starts, including seven complete games and five shutouts. Over 72 innings, Valenzuela allowed just 43 hits, 17 walks (against 68 strikeouts) and two home runs (both in the eighth start).

During this extraordinary stretch, “Fernandomania” was born. Valenzuela made his first appearance on the cover of Sports Illustrated. A young female Mexican American fan ran onto the field during one of his starts and kissed him.14 Reporters streamed to his hometown to learn more about the phenom. Whenever he pitched, fans flocked to the ballpark. Valenzuela made 12 starts at Dodger Stadium during the strike-shortened 1981 season, and 11 were sellouts.15 According to figures reviewed by The Sporting News, the average attendance (home and away) was 39,460 in the 25 Dodgers’ games that Valenzuela was scheduled to pitch in 1981 versus 30,800 in the 85 games when he was not, an increase of 8,660.16 To Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles, Fernando was relatable and a hero. Dodger Stadium became a tapestry of Mexican flags, sombreros, and mariachi bands amid a blue wave of Fernando apparel and gear.

Valenzuela’s stature and delivery were part of his mystique. He was officially listed at 5’11” and variously at 180-195 pounds. Physically, at age 20, Valenzuela looked older with his bushy long hair and pudgy face and shape. When responding to reporters who wondered how a major league pitcher lived in his soft, undefined frame, Valenzuela conceded he was not strong but boasted that he was always loose.17 Whatever his physique, Valenzuela was a good athlete. He was one of the better hitting pitchers of his era (over his career he won two Silver Slugger awards, hit 10 home runs and was 7 for 19 as a pinch-hitter), won a Gold Glove and was even used as a position player in emergencies. His signature delivery featured a windup and corkscrew motion where he kicked his leg high, paused at the top as he clasped his hands above his head and looked to the sky above, then found the catcher’s target with his eyes as he uncoiled his body and uncorked his screwball.

Valenzuela spoke only Spanish when he was called up by the Dodgers. Though he understood some English, he was a shy, homesick teenager and understandably struggled with the language, Southern California culture and his instant fame. Early on he regularly stayed alone in his hotel room and watched television (Mexican and American movies, cartoons, and soap operas). His business agent helped him manage endorsement proposals and interview requests. Jaime Jarrín, the Dodgers’ longtime Spanish-language radio voice, served as Valenzuela’s interpreter for the English-speaking media. Lasorda knew enough Spanish from the winter leagues to communicate with Valenzuela. With so many Spanish native speakers living in Los Angeles, Valenzuela was able mostly to continue speaking in his native language, which eased his transition to some extent but also added to his mystique with the press and fans.18 Valenzuela became more confident with the media over time, but away from the ballpark he mostly liked to stay at home and play with his family. One exception was regularly visiting school kids.19

More of Valenzuela’s easy-going personality, charm and playfulness emerged in the clubhouse. He was a good teammate and easy to like. One of his favorite pranks was ensnaring the feet of unsuspecting teammates with lassos he made from twine as they walked past.20 Lasorda praised Valenzuela’s heart and competitive spirit throughout his career.

In June 1981, the season and Fernandomania were temporarily interrupted. During the 50-day players’ strike, Valenzuela met Mexico President José López Portillo during an exhibition appearance, another testimony to his new stardom.21 After the strike ended in August, Valenzuela became the second rookie pitcher to start an All-Star Game. He pitched a scoreless first, and the National League eventually prevailed, 5-4, to extend its steak to 10 straight wins over the American League. Valenzuela won four more decisions in the regular season after games resumed, and he ended the season with 16 wins (including playoffs) and a World Series championship.22 The honeymoon continued after the season – Valenzuela married his long-time girlfriend, Linda (Burgos), a 20-year-old elementary school teacher from Mexico.

Valenzuela made $42,500 ($10,000 above the league minimum) in 1981. He instructed his agent to renegotiate the contract after the season. Based on his client’s pitching results and impact on gate receipts, Valenzuela’s agent advised the Dodgers that the pitcher would not report to spring training without a new deal and was prepared to sit out the 1982 season unless he was paid $1 million.23 The negotiations became contentious, and Valenzuela took a public relations hit with some fans.24 The Dodgers dug in and, after a short holdout from spring training, Valenzuela finally accepted the club’s best offer, $350,000.25 After 19 more wins in 1982, Valenzuela won $1 million in arbitration for 1983, then the highest annual award for any player.26

Valenzuela became the workhorse of the Dodgers pitching rotation that included past or future All-Stars Reuss, Hooton, Bob Welch and, later, Orel Hershiser and Rick Honeycutt. Mike Scioscia became Valenzuela’s personal catcher. Through the 2024 season, they are one of only 15 battery-mates in MLB history with at least 239 games started together.27

Valenzuela’s career high strikeout game came during the 1984 season. On May 23, he fanned 15 batters in a 1-0 victory over Steve Carlton and the Philadelphia Phillies. He allowed just three hits and drove in the game’s only run to snap the Phillies’ 10-game winning streak.

During the 1985 season, on September 6, Fernando started opposite New York Mets’ phenom Dwight Gooden at Dodger Stadium. It was an epic pitchers’ duel – Gooden pitched nine scoreless innings before being lifted for a pinch hitter; Valenzuela pitched 11 scoreless innings, the longest outing of his career. The Mets eventually prevailed, 2-0, in 13 innings.

In 1986, Valenzuela had his lone 20-win season. He pitched 20 complete games (best in MLB), good for 21 victories (best in NL). On June 13 of that season, Valenzuela formed the first Mexican-born battery in MLB history with backup catcher Alex Treviño. One month later, in his last All-Star Game appearance, Valenzuela tied a record by striking out five consecutive batters.

Valenzuela worked at least 250 innings for the sixth straight season in 1987. However, arm and shoulder problems ended that string in 1988, when his won-loss record was just 5-8 in 22 starts. He made his first trip to the disabled list in 1988 and missed the playoffs as the Dodgers won another World Series title. In 1989, Valenzuela had a second straight losing season (10-13).

On June 29, 1990, during his final season with the Dodgers, Valenzuela no-hit the St. Louis Cardinals. Extraordinarily, earlier that day former teammate Dave Stewart threw a no-hitter for the Oakland A’s against the Toronto Blue Jays. It was the only time since 1898 that two MLB pitchers completed no-hitters on the same day.28

The no-hitter turned out to be the last major highlight of Valenzuela’s tenure with the Dodgers. To his surprise and disappointment, the team released him prior to the start of the 1991 season. He was signed by the California Angels but made just two major-league appearances that season. After pitching in Mexico the following year, Valenzuela returned to the majors and pitched four more seasons – for Baltimore in 1993, Philadelphia in 1994, and San Diego in 1995 and 1996. In 1997, he made just five appearances for St. Louis, marking the end of his MLB pitching career.

In subsequent years, Valenzuela pitched several stints in the Mexican Pacific League, well into his 40s. He thrived on the competition and playing in his native country. Attendance continued to spike whenever Fernando pitched.29

In 2003, Valenzuela joined Jarrín and the rest of the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcast team in the radio booth. Citing numerous sources, the press reported that he had refused multiple Dodgers’ invitations to honor him after his retirement as a player because he was still angry at the team for waiving him in 1991. Following Valenzuela’s release, some Mexican American and Latino fans had wanted to boycott the team. But when asked, Valenzuela generally denied reports that he held a grudge.30

In 2015, Valenzuela became a US citizen. President Barack Obama appointed him a presidential ambassador for citizenship and naturalization. (Valenzuela had been previously invited to the White House during the 1981 season for a luncheon that President Ronald Reagan hosted for the President of Mexico. Some have credited Valenzuela and Fernandomania with helping to shift attitudes toward more openness to immigration reform in the 1980s.)31 Valenzuela supported the Dodgers’ community and Latino initiatives. In recognition of his continued community involvement, the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities Program (RBI) honored him with a Lifetime Achievement in 2007.32

The Dodgers retired Valenzuela’s uniform number 34 during the 2023 season in a ceremony at Dodger Stadium. Valenzuela threw out the first pitch to his longtime battery mate Scioscia.33 There had been calls to retire Valenzuela’s uniform number years earlier, but the Dodgers then maintained a long-standing team policy that a player could not have his number retired unless he was first voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.34 Still, it was noteworthy the Dodgers did not assign Valenzuela’s number to any other player after he left the club.35

Valenzuela and his wife Linda resided principally in Los Angeles. They had four children: Ricky, Fernando Jr., Linda, and Maria Fernanda.36 In 2005, when Valenzuela pitched for a team in Mexico, one of his teammates was Fernando Jr.37

Valenzuela remained humble about his impact on baseball and the Mexican American community. But he was especially proud of his “Be Smart-Stay in School” program, which he called his “best pitch.” Valenzuela, who dropped out of school early to play baseball, regularly spoke to area children about the importance of school.38 “In sports, you win and you lose,” he recalled telling the young students, “but in education, you only win.”39

For his MLB career Valenzuela posted a 173-153 won-lost record and 3.54 ERA. In his 11 seasons with the Dodgers, his record was 141-116 (3.31 ERA).40 He pitched well in three postseasons for L.A. (the 1981 championship team, 1983 and 1985), compiling a cumulative 5-1 mark (1.98 ERA).

Valenzuela was arguably the majors’ best pitcher over his first six full seasons (1981-1986). During that peak period, he was a NL All-Star each year, led hurlers in innings pitched (1,537) and shutouts (26), and was second only to Detroit’s Jack Morris in wins (97) and complete games (84). Valenzuela’s 2.97 ERA was the lowest among all starters with at least 100 games started during that span, and he accumulated 27.1 WAR (second only to Toronto’s Dave Stieb among starting pitchers). Valenzuela made 255 consecutive starting turns from 1981-1988, a testament to his durability. Over the 1981-1987 seasons, he averaged nearly eight innings and 121 pitches per start – certainly more than starters in 21st century baseball but less extraordinary for the period. Valenzuela started 208 more games in the second phase of his career (1988-1997), but his innings and effectiveness waned. In assessing Valenzuela’s injuries and performance decline, most commentators focused on the cumulative effect of all the pitches thrown. As for Valenzuela himself, he did not like coming out of games and generally balked at the notion that he was overused.41

Valenzuela was elected to the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame (2011 class), Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame (2013 class) and Mexico Baseball Hall of Fame (2014 class), affirmation of his immense contributions on and off the baseball field in the US and Mexico. For his career, he ranks in the top ten among all Latino MLB pitchers in wins, complete games, shutouts, innings pitched and strikeouts.42 In 2005, Valenzuela was selected by fans as one of three starting pitchers (along with Pedro Martinez and Juan Marichal) on the Latino Legends Team (an all-time all-star team of Latino MLB players), a testimony to how Valenzuela was viewed soon after he retired.

Based on Bill James’ similarity scores, Valenzuela was most similar to fellow-Dodger Don Drysdale after his age-26 season (1987) and to Steve Carlton after his age-30 season (1991). Valenzuela was not able to maintain a similar level of performance and effectiveness. Consequently, he was not inducted to Cooperstown by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (maxing out at 6.2% of the necessary 75% of the votes on the 2003 ballot).

Over the years many commentators and fans have evaluated the MLB Hall of Fame case for Valenzuela. Those who favor his induction tend to emphasize Valenzuela’s impact on gate receipts and his cultural impact beyond the baseball field. His impact was exceptional: Bud Selig, former commissioner of MLB, was quoted as saying “The impact he made not only in Southern California but in all of the country, it was really great for the game.”43 Peter O’Malley, who took over ownership of the Dodgers from his father, believed Valenzuela’s impact on baseball and the community was, if anything, underestimated.44 Jay Jaffe has written persuasively about Valenzuela’s hybrid case for Cooperstown (“one that goes far beyond the numbers”) and how Hall of Fame voters have struggled to develop a template for players that present a hybrid case. Jaffe concludes that Valenzuela’s numbers are not MLB Hall of Fame-worthy but opines that Valenzuela is imminently deserving of the O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of his overall contributions to the game.45

As improbable and serendipitous as “Fernandomania” was for the Dodgers and MLB, it was not altogether accidental. Team owner Walter O’Malley moved the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. Dodger Stadium at Chavez Ravine opened for the 1962 season, but its construction was tainted by an historical stain on the city’s relationship with the Mexican American and Latino communities. Many Mexican American families who had lived in the Chavez Ravine neighborhoods had been evicted in the 1950s by eminent domain and by force to make room for planned public housing. Those plans were later scrapped, but when the city of Los Angeles offered O’Malley the site to build Dodger Stadium, he inherited that bitter legacy. Local baseball was a favorite pastime of the Mexican American and Latino communities before the Dodgers relocated, but feeling marginalized by the city and the team, they refused to come to Chavez Ravine and root for the Dodgers. O’Malley continued the integration of the Dodgers after he became majority owner in 1950 (Branch Rickey had signed Jackie Robinson in 1947) and wanted a club that reflected the community. As the story goes, O’Malley instructed general manager Al Campanis to find a Mexican Sandy Koufax; in turn, Campanis instructed scout Mike Brito. The Dodgers found their man, but O’Malley died in 1979, so he missed Valenzuela’s rise to stardom and Fernandomania. Jarrín estimated that Latinos accounted for between 42% and 46% of all Dodgers fans at the end of the 2022 season. When Jarrín first started in 1959 and the team played games in the L.A. Coliseum, that number was between 8% and 10%.46 One former team executive guessed that attendance at Dodger Stadium would be 10% to 20% lower had Valenzuela never played.47 Jarrín also felt that only Koufax and Lasorda have been cheered by fans the way they cheered Valenzuela.48

In a team statement following Valenzuela’s death, Stan Kasten remarked that “[Fernando] is one of the most influential Dodgers ever and belongs on the Mount Rushmore of franchise heroes. He galvanized the fan base with the Fernandomania season of 1981 and has remained close to our hearts ever since, not only as a player but also as a broadcaster. He has left us all too soon.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Henry Kirn.

Photo credits: SABR-Rucker Archive (top and middle) and Los Angeles Dodgers (bottom).

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied primarily on the numerous clippings from Valenzuela’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. The author relied primarily on baseball-reference.com and stathead.com for statistics. Also helpful were “Fernando Nation,” ESPN Films: 30 for 30, February 26, 2018, “Fernandomania@40” Documentary, Los Angeles Times, 2021, and Jason Turbow, They Bled Blue: Fernandomania, Strike-Season Mayhem, and the Weirdest Championship Baseball Had Ever Seen: The 1981 Los Angeles Dodgers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019).

Notes

1 Valenzuela also leads all Mexican-born players in games started (424), complete games (113), shutouts (31) and innings pitched (2,930).

2 Jay Jaffe, “The Dodgers Finally Call Fernando Valenzuela’s Number,” fangraphs.com, August 14, 2023, https://blogs.fangraphs.com/the-dodgers-finally-call-fernando-valenzuelas-number, last accessed February 25, 2025.

3 Jason Turbow, They Bled Blue: Fernandomania, Strike-Season Mayhem, and the Weirdest Championship Baseball Had Ever Seen: The 1981 Los Angeles Dodgers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019), 58.

4 Turbow, They Bled Blue, 53-54. Robert Montemayor, “From Mexico with Mystery,” Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1981, Part III: 1.

5 Montemayor, “From Mexico with Mystery,” 1, 10-11.

6 Montemayor, “From Mexico with Mystery,” 1.

7 Montemayor, “From Mexico with Mystery,” 10.

8 Turbow, They Bled Blue, 58-64.

9 Jerry Crowe, “A screwball chain of events led the Dodgers to Fernando Valenzuela,” Los Angeles Times, March 27, 2011, https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-xpm-2011-mar-27-la-sp-crowe-20110328-story.html, last accessed May 5, 2025.

10 In the 1986 All-Star Game, Valenzuela struck out Don Mattingly, Cal Ripken, Jr. and Jesse Barfield in the fourth inning, and Lou Whitaker and pitcher Teddy Higuera to start the fifth inning.

11 Bruce Schoenfeld, “The Mystery of the Vanishing Screwball,” New York Times, July 10, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/13/magazine/the-mystery-of-the-vanishing-screwball.html, last accessed February 25, 2025.

12 Lasorda, Valenzuela’s only manager with the Dodgers, had replaced legendary manager Walter Alston after the 1976 season. The Dodgers had won NL pennants in both the 1977 and 1978 seasons but had lost to the New York Yankees in both World Series. See Turbow, They Bled Blue, Chapter 4, “Mania”, 51-70, for further reading on Valenzuela’s rise to the Dodgers and his phenomenal start to the 1981 season.

13 “Fernando Nation,” ESPN Films: 30 for 30, February 26, 2018.

14 Scott Ostler, “Fernando Valenzuela: He Has the Baseball World in His Hands,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1981: 3, 9.

15 Gordon Verrell, “Valenzuela Dons N.L. Rookie Pitcher Crown,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1981: 48.

16 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Player of Year Valenzuela is the King of Fan Appeal,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1981: 42. Jaime Jarrín estimated that as many as 20 million fans in Mexico listened to games on the Dodgers’ Spanish-language radio network. Turbow, They Bled Blue: 150 (footnote).

17 Montemayor, “From Mexico with Mystery,” 1.

18 Tony Castro, “Something Screwy Going on Here,” Sports Illustrated, July 8, 1985: 31-37.

19 David Leon Moore, “Fernando puts family before fame,” USA Today, August 14, 1986:1C-2C.

20 Turbow, They Bled Blue, 79. Castro, “Something Screwy Going on Here,” Page 31. Moore, “Fernando puts family before fame,” Page 2C.

21 Bill Brubaker, “Fernando: I wanted to be ready,” New York Daily News, June 27, 1981, Back Page and Page 33.

22 Valenzuela ended the 1981 regular season with a 13-7 won-loss record and 2.48 ERA, including an MLB-leading eight shutouts in just 25 starts in the shortened season. It is interesting to note that the 1981 championship Dodgers had a deep roster of – like Valenzuela – All-Stars but no Hall of Famers, but by the 1983 season Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Ron Cey, and Reggie Smith had all left for other teams.

23 Jack Lang, “Valenzuela Takes Rift to the People,” New York Daily News, February 16, 1982, Back Page and Page 29.

24 Bill Brubaker, “Fernando’s Wild Pitch,” New York Daily News, March 21, 1982, Page 27.

25 Ira Berkow, “Valenzuela’s Back, and So Is Tumult,” New York Times, March 25, 1982, Page B17 and B20.

26 “Valenzuela Granted $1 Million,” New York Times, February 20, 1983, Section 5 Page 9.

27 Doug [sic], “200 Game Batteries,” highheatstats.com, January 28, 2016, http://www.highheatstats.com/2016/01/200-game-batteries/, last accessed February 25, 2025.

28 For more reading on this game, see Carter Cromwell, “June 29, 1990: Fernando Predicts, Then Throws No-Hitter for Dodgers,” https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-29-1990-fernando-valenzuela-predicts-then-throws-no-hitter-for-dodgers/, last accessed June 20, 2025.

29 James F. Smith, “Winter Wonder: Valenzuela Still a Throwback, Pitching Well in Mexico and Reminding Fans of How It Was,” Los Angeles Times, December 30, 2000: D1, D15.

30 Bill Paschke, “Waiting for Fernando: The Dodgers Keep Trying to Include Valenzuela in a Celebration of his Legacy, but He Declines,” Los Angeles Times, July 8, 2001.

31 Castro, “Something Screwy Going on Here,” Page 36-37; Dylan Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela was a game changer for the Dodgers, baseball, and Los Angeles,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2011, https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-xpm-2011-mar-30-la-sp-0331-fernandomania-20110331-story.html, last accessed May 5, 2025. “Fernandomania@40” Documentary, Los Angeles Times, 2021, accessed on YouTube September 2, 2024.

32 ”Dodgers broadcasters,” mlb.com, https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/team/broadcasters, accessed April 20, 2024.

33 Jay Jaffe, “The Dodgers Finally Call Fernando Valenzuela’s Number.”

34 The Dodgers have made one exception to this policy. Walter O’Malley retired Jim Gilliam’s uniform number 19 following his sudden death in 1978. Most other MLB teams have not traditionally adhered to this policy. Ron Cervenka, “The Dodgers ‘unofficial’ retired number,” thinkbluela.com, July 16, 2015, https://thinkbluela.com/2015/07/the-dodgers-other-sacred-uniform-number/, last accessed February 25, 2025.

35 Cervenka, “The Dodgers ‘unofficial’ retired number.”

36 ”Dodgers broadcasters.”

37 ”Fernando Valenzuela,” baseball-reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Fernando_Valenzuela.

38 Tony Castro, “Something Screwy Going on Here,” Page 37.

39 Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela was a game changer.”

40 Over his ten full-time seasons between 1981-1990 with the Dodgers, Valenzuela was fourth among all MLB pitchers in wins (139), third in games started (320), second in complete games (107), first in shutouts (29), and second in innings pitched (2,331).

41 See Bruce Schoenfeld, “The Mystery of the Vanishing Screwball,” New York Times, July 10, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/13/magazine/the-mystery-of-the-vanishing-screwball.html, accessed April 22, 2024; Warren Corbett, “Hubbell’s Elbow: Don’t Blame the Screwball,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011; and Jaffe, “The Dodgers Finally Call Fernando Valenzuela’s Number” for further reading on this topic.

42 ”Latino lifetime leaders,” latinobaseball.com and stathead.com. https://latinobaseball.com/top-all-time-latino-player-statistics/, last accessed February 25, 2025.

43 Dylan Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela was a game changer.”

44 “Fernandomania@40” Documentary.

45 Jaffe, “The Dodgers Finally Call Fernando Valenzuela’s Number.”

46 Cora Cervantes, Edwin Flores, Gadi Schwartz, “A Spanish-Language Legend Who Made History and Brought the Dodgers to Latino Families is Saying Goodbye,” nbcnews.com, October 12, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/jaime-jarrin-legendary-latino-voice-dodgers-retires-rcna48391, last accessed February 25, 2025. The Dodgers had survey research in 2011 that indicated about 40% of their fan base was Latino. See Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela was a game changer.” For further information on the stadium construction legacy and Valenzuela’s impact, see Turbow, They Bled Blue, Chapter 5, “Buried,” 71-85, and “Fernandomania@40” Documentary. For further reading on “Fernandomania,” the 1981 season and the extraordinary impact Valenzuela had on Mexican American fandom and the Dodgers’ fanbase, see SABR journal article by Jason Scheller, “’Viva, Valenzuela!’ Fernandomania and the Transformation of the Los Angeles Dodgers,” published in Dodger Stadium: Blue Heaven on Earth (2024).

47 Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela was a game changer.”

48 Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela was a game changer.”

Full Name

Fernando Valenzuela Anguamea

Born

November 1, 1960 at Navojoa, Sonora (Mexico)

Died

October 22, 2024 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.