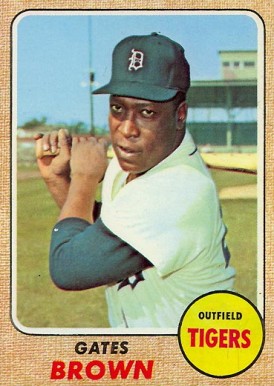

Gates Brown

Ask any serious Tigers fan over a certain age and they’ll tell you that the sound of Tiger Stadium was always a little bit louder than normal when Gates Brown was announced as a pinch-hitter. And why not? After 13 seasons in Detroit, not only did the “Gator” retire as the American League’s all-time pinch-hitting king, but so many of his hits were of the clutch variety, either tying the game or putting the team ahead. One would think that in order to have enjoyed that kind of success off the bench, Brown would’ve had to be ready to hit at all times. You would think he studied pitchers like a hawk for nine innings – trying to gain any advantage he could for when he took the plate. But surprisingly, that wasn’t always the case for Gates Brown.

Ask any serious Tigers fan over a certain age and they’ll tell you that the sound of Tiger Stadium was always a little bit louder than normal when Gates Brown was announced as a pinch-hitter. And why not? After 13 seasons in Detroit, not only did the “Gator” retire as the American League’s all-time pinch-hitting king, but so many of his hits were of the clutch variety, either tying the game or putting the team ahead. One would think that in order to have enjoyed that kind of success off the bench, Brown would’ve had to be ready to hit at all times. You would think he studied pitchers like a hawk for nine innings – trying to gain any advantage he could for when he took the plate. But surprisingly, that wasn’t always the case for Gates Brown.

Once in 1968, Mayo Smith decided to put in his pinch-hitting specialist far earlier in the game than normal. Brown, who usually didn’t come off the bench until a tight spot near the end of the game, was caught off-guard. “I was sitting at the end of the dugout, eating a couple of hot dogs,” he recalled. “It was only the fifth inning (and) I never expected Mayo to call on me to pinch-hit that early.” Since he didn’t want Smith – who often harped on Brown to lose a few pounds – to see him eating during the game, Brown quickly shoved the hot dogs down his shirt before heading to the plate. “That’s the only time I ever wished I’d strike out,” he said. But being the clutch hitter he was, he didn’t get his wish. Instead, he cracked a double and ended up having to slide head-first into second. While Tigers fans roared and cheered, Brown realized he had made quite a mess of himself. “I had mustard and squashed meat all over me,” he laughed, recalling that all his teammates were bent over laughing.1

So despite his success as one of the greatest major-league hitters off the bench, Gates Brown wasn’t a pinch-hitting robot after all. He was simply one of the guys. He played poker with teammates. He snored. He played catch with relievers during games. He was a press favorite. But most importantly, he always supported his teammates – so much so that his first big-league manager, Charlie Dressen, often referred to him as “Governor Brown.” But that was Gates Brown in a nutshell – a team player who always said and did the right things to help his team win.

William James “Gates” Brown was born in Crestline, Ohio, on May 2, 1939 (the same day that Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games streak came to an end). His father, John William Brown, a Georgia native, was a laborer working for the US government’s Depression-fighting WPA. Crestline was a town along the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, and by the time of the 1950 census he was listed as “laborer, railroad.” He and Phyllis Brown, a native Ohioan, had six children.

Gates grew to be 5-feet-11 and 220 pounds. He batted left-handed, but threw right-handed and played in 1,051 major-league games, all for the Detroit Tigers.

He was nicknamed Gates by his mother when he was a toddler. He claimed he didn’t know why. “I had it long before I went to school. … Maybe it had something to do with the way I walk – kind of bowlegged, I really don’t know.”2

Crestline, like much of northern Ohio in the 1940s and ’50s, wasn’t the greatest area to grow up in. It was flat, desolate, and poor. Most youngsters from the area got in trouble with the law at some point. A sociologist would say it wasn’t their fault they turned to a life of crime, but was a result of where they grew up.

Brown didn’t make it out of Crestline with a clean record. Even though he was a standout football star at Crestline High School, he got into more than his fair share of trouble growing up. When he turned 18, he was arrested for breaking and entering and was sent to the nearby Mansfield State Reformatory. (The prison was used in the film The Shawshank Redemption.)

Even though Brown had played some baseball in high school, it was in Mansfield that his talents as a ballplayer were developed. At 5-feet-11 and 200-plus pounds of pure muscle, he was encouraged by a prison guard who coached the institution’s baseball team to try out at catcher. In awe of his raw ability with the bat – and encouraged that baseball might lead Brown out of a life of crime – the coach, Chuck Yarman, wrote to several major-league teams, including the Tigers.3

In the fall of 1959, Detroit sent scouts to the prison to see Brown. Impressed, one of them called onetime Tiger Pat Mullin, later the team’s top scout. Mullin made the trek from Detroit to see for himself. After Brown belted a daunting home run in Mullin’s presence, the Tigers decided to help him get paroled a year early. He was signed to a $7,000 bonus pact almost immediately upon his release.

Brown has said that other clubs, including the Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox, were interested in springing him. But he stuck with Detroit because “they didn’t have any Negroes at that time and I figured they’d have to have some soon.”4 In fact, Ozzie Virgil, a Puerto Rican, had joined the Tigers in 1958 – becoming the Motor City’s first Black ballplayer. But Brown was right in that the Tigers obviously lacked the integration of most other big-league clubs in the late 1950s.

Before Brown’s first professional season, 1960, Mullin advised him to give up catching and switch to the outfield. More concerned about staying out of trouble than he was about a position change, he was fine with the new position.

Brown – on legal probation from Mansfield during his first season – joined the Tigers’ organization in Duluth that year. He shined almost immediately – especially for someone only a few months out of prison. In 121 games, he hit .293 with 10 homers. He also led the Northern League with 13 triples and was second in stolen bases (30) and runs scored (104). But his real character test wouldn’t come until later.

The following year he headed south to Durham of the Carolina League. It was here that Brown found out firsthand that being Black and an ex-con was fuel for the fire for Southern crowds. “It was tough just being a Negro down there,” he said. “I had to contend with people calling me ‘n—–” and other stuff.”5

Being an ex-con didn’t help as Southern newspapers printed stories about his criminal history, leading to more quips and threats from the crowds. “They called me all the names, ‘Con,’ ‘Jailbird,’ the whole thing. They were pretty vicious,” Brown recalled. But he had to learn to ignore the jeers and to use the negativity as motivation to improve. “Some of the guys wanted to go up into the stands after those people, but I told them to just let it lay. It made me do better. It made me try harder. I decided that they could beat me physically, but no way were they going to beat me mentally. And do you know something, I hit the ball hard that season and led the league in hitting,” topping the circuit in 1961 with a .324 mark. His outstanding play began to win over the same Durham fans who had heckled him earlier in the season. “By the end of the year, they were all on my side,” Brown said, laughing.6

After showing continued success at the minor-league level – including another .300 campaign for Denver in 1962 – it was clear that Brown was on the fast track to join the big club. And with the Tigers’ lack of early-season success in 1963, Brown was called up from Triple-A Syracuse on June 17 – one day before Dressen was named the team’s new manager. It would be Dressen who would call on Brown to take his first major-league hacks.

Brown officially debuted for the Tigers against the Boston Red Sox on June 19 at Fenway Park. With Boston up 4-1 in the fifth inning, Brown entered the game as – what else – a pinch-hitter for pitcher Don Mossi.

With Dressen getting his first look at the young outfielder, the situation was much like when Pat Mullin saw Brown play at Mansfield for the first time. As it happened, Mullin was at Fenway Park that day – having been made Dressen’s first-base coach. Again, as he had during his Mansfield tryout, Brown did not disappoint his onlookers. He hit a 400-foot home run well into the Boston sky, becoming only the third Tiger in history to homer in his first at-bat.

Brown remained with the club for the rest of the season, primarily as a pinch-hitter. Detroit rebounded with him on the team and had a winning record for the rest of the year. Overall, Brown hit .268 with two home runs in his rookie season. He stuck with the Tigers in 1964, primarily as the starting left fielder. Playing alongside Al Kaline in right field and a troika (Bill Bruton, George Thomas, and Don Demeter) in center, Brown hit .272 with 15 home runs and was second on the team with 11 stolen bases.

Despite his solid 1964 season, however, Brown lost his starting job in the outfield in 1965 to the young power hitter Willie Horton. And even though he was disappointed in returning to his role as a pinch-hitter and reserve outfielder, Brown would never let his personal frustration get in the way of the team. He slugged 10 home runs that season in barely half the at-bats he had in 1964. And despite his stocky 225-pound frame, he also stole six bases and was regarded unofficially as the fastest Tiger on the team. Brown didn’t know it then, but he was on his way to becoming the most successful pinch-hitter in American League history.

Despite Brown’s clutch contributions, his reserve status – and a budding mix of young outfielders – made it difficult for him to get raises from his bosses in Detroit. In fact, prior to the 1965 season, Brown had to pass up winter ball for the first time. With a wife and child plus a second on the way, Brown took a second job as a furniture salesman in the offseason.

Brown pressed on, however, and returned in 1966 and had similar success in the same role – batting .325 as a pinch-hitter. Overall he hit .266 with 7 home runs in 169 at-bats. Although he remained quietly disappointed with his role, it was clear that Brown was the Tigers’ best offensive option off the bench.

Tragedy befell Brown and the Tigers that season, however. Charlie Dressen died on August 10. Dressen had been suffering from heart and kidney problems for most of the season.

Brown struggled with injuries in 1967 before finally being shelved with a dislocated wrist. Even when he played, he never could find his swing under new manager Mayo Smith. As a pinch-hitter, he hit only .160 (4-for-25). However, that Tigers team nearly made the World Series before they were beat out by the “Impossible Dream” Red Sox on the final day of the season. Mayo Smith and the rest of the Tigers vowed to return to the 1968 season with a vengeance. But the greatest turn-around of all would come from Brown.

Discouraged by his poor season in 1967, Brown came to spring training on a mission in 1968. He was no longer upset about a lack of playing time, he just wanted to contribute. The Tigers, however, weary of Brown’s poor and injury-filled campaign in 1967, decided to bring back Eddie Mathews as the team’s primary left-handed pinch-hitter. General manager Jim Campbell and Smith even said that they thought about trading Brown, but couldn’t come close to pulling a trade because Brown had packed on a few pounds while waiting for his wrist to heal, a turnoff for prospective trading partners.

Brown got his chance to prove them wrong, however, on the second day of the season; when Smith, having already used Mathews earlier in the game, called on Brown to pinch-hit in the ninth inning in a tie game. Brown grabbed a bat and hit a game-winning home run off John Wyatt of the Boston Red Sox. It was how the 1968 Tigers won their first game of the season.

Brown did everything he could to tarnish the image of what would be known as the Year of the Pitcher. He hammered six hits in his first 10 pinch-hit at-bats on his way to an AL-record 18 pinch hits that season. Tigers fans soon became accustomed to watching him come off the bench and deliver over and over in key situations. But none was more key than during a Sunday doubleheader on August 11 against the defending American League champion Red Sox.

In the lidlifter that day, the Tigers were in an extra-inning struggle with the Red Sox until Mayo Smith finally found a time for Brown to get in the game in the bottom of the 14th inning. Tiger Stadium erupted when he was announced. But their cheers were nothing compared to when Brown smacked the game-winning home run a minute later.

Then in the second game, Brown strode to the plate in a tie game in the bottom of the ninth. With Mickey Stanley creeping off third, he singled to right to drive in the winning run, Giving him an unheard-of two game-ending hits in the same day. Even 16-year vet Kaline admitted he had never heard the Tiger Stadium crowd cheer the way they did for Brown that day.

In fact, Brown hit so unbelievably well in 1968 that Smith even started him in 16 games. Not bad for a guy who was trade bait when the season began. In the end, Brown hit an astounding .370 in 1968 – more than over 100 points higher than his career average, 135 better than the team average, and 140 better than the American League’s collective average. He was the only full-season Tiger to hit above .300 that season. He also averaged an extra-base hit every 6.9 at-bats – a remarkable stat when you consider that the mighty Álex Rodríguez averaged one every 7.2 at-bats in his MVP season of 2007.

Brown was not only clutch with the bat in 1968, he was also clutch as a teammate. One night during the season, he interrupted a melee between Denny McLain and Jim Northrup and made them understand the importance of what the team was trying to accomplish as a whole. During a road trip in the middle of the 1968 season, Brown was playing poker with a bunch of other players, including Northrup and McLain. Halfway through a hand, Northrup caught McLain cheating. Enraged, he flew across the bed and grabbed McLain by the throat. John Hiller, who was seated next to Brown, recalls Northrup screaming, “I’m gonna kill you, you bastard! I’m gonna kill you!” Red-faced and exasperated, Northrup continued to wring McLain’s neck in anger. But he was eventually pulled off from behind by Brown. A shocked Hiller remembered Brown looking Northrup dead in the eye and saying, “You’re not gonna touch him until after we win the pennant. Then he’s all yours.”7

Brown also remained popular with the Detroit writers that season. When asked about his remarkable success in the clutch, he developed a common response to give to reporters: “I’m square as an ice cube, and I’m twice as cool.” Detroit media couldn’t get enough of Gates.

Neither could Tigers fans. When the World Series rolled around and the Tigers lost Game One to St. Louis’s Bob Gibson – who also struck out 17 – Mayo Smith was bombarded by letters to put Brown into the starting lineup. One Tigers fan even wrote Smith asking him to start Brown at shortstop and bat leadoff during the series. “That guy must be nuts,” reacted Brown when told of the letter.8

Brown had only one appearance during the World Series: a pinch-hit fly out to left off Gibson in Game One. But for anyone who remembers how untouchable Gibson was that October day, it’s a miracle any man could come off the bench and even touch the ball.

Throughout the rest of his career, Brown enjoyed continued success as a pinch-hitter – including a .346 pinch-hitting campaign in 1971 – but nothing quite like the 1968 season, although he did enjoy more time in the baseball spotlight by becoming Detroit’s first designated hitter in 1973, a position tailor-made for the game’s Gates Browns.

Moreover, Brown became so beloved that some sportswriters who were adamantly against the DH when it was first implemented eventually said it didn’t bother them as much as they thought it would. One of the reasons: It was great for Tigers fans to see Brown at the plate every day.

The whole country got a chance to see Brown in July 1974 when Joe Garagiola, host of NBC’s pregame show Baseball World of Joe Garagiola, did an unusual two-part story on Brown. Garagiola rarely devoted his weekly show to anyone for two separate shows, but did so for Brown. The shows featured Brown and Garagiola back in Brown’s old stamping grounds at the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield. The program consisted of an interview in Brown’s former prison cell, as well as several rap sessions with current inmates.

Brown said he agreed to the interview inside the prison itself because “if I can help a few people who are mixed up by doing this [interview], it will be well worth it.” But he also mentioned that even if you did make the mistake of breaking the law, incarceration didn’t mean the end. “Just because a man has been in jail doesn’t mean it has to be the end of his whole life,” Gates told the inmates.9

After suffering through a 102-loss Tigers season in 1975, Brown decided to hang up his spikes at age 36. However, he loved the game too much to give it up completely. So he became a scout for the club less than three weeks after the season ended. Almost immediately Brown went from sitting in a major-league dugout to scouting teams in Florida, assisting in the free-agent draft; instructing the Tigers’ rookie-league team, and visiting various colleges nationwide to find new talent.

Brown continued his work as a scout until 1978, when he returned to the Tigers to become the new hitting coach under manager Ralph Houk. The Tigers’ team batting average rose from eighth in the American League in 1977 to second overall in Brown’s first season. That year the Tigers also enjoyed their first winning season in five years.

When Sparky Anderson arrived in Detroit in 1979, he kept Brown on. He helped bring along the hitting talents of Kirk Gibson, Alan Trammell, and Lou Whitaker. Brown remained with the Tigers through their World Series championship in 1984. He wanted to continue coaching the Tigers beyond 1984 but couldn’t agree with the team on a contract extension. He quit on November 14, 1984 – almost 25 years after he signed his first professional contract fresh out of Mansfield.

Things weren’t always rosy for Brown in his years since the 1984 championship. In 1991 he was part of a business group that purchased Ben G Industries, a plastics molding company that was relocated from the Detroit suburb of Mount Clemens to Detroit after its purchase. The company was doomed almost from the start. First it was alleged that the previous owners had stolen $458,000 from Ben G before it was sold to Brown’s group. Then the Internal Revenue Service got involved and found that as the company’s president, Brown had failed to oversee the payment of taxes during his first two years of ownership. A civil suit against Brown by the IRS sought more than $61,000.10 However, he never faced criminal charges.

Brown also had to settle another IRS allegation a few months before the Ben G trial began. This time it was at the personal level. Brown and his wife, Norma, were accused of shorting income on their personal taxes and ordered to pay more than $36,000 in back taxes and penalties dating from 1992 to 1997.

Brown was not forgotten by the baseball world, however. He was inducted into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in 2002. Beside Brown during his acceptance speech were his former hitting pupil, Lance Parrish, and former big-league pitcher Jim Kaat.11 Many of the voters said that Brown’s amazing story was a huge reason why they chose him.

Brown always liked to revisit and reflect upon that magical season of ’68. He had reached the pinnacle of his profession. He was a World Series champion. His climb from a prison cell to shaking hands with the likes of Bob Hope and Ed Sullivan was a great comeback story. But if you asked Brown, his contribution to the 1968 season was for his parents.

“I can never make up for all the grief I gave them in my life. I can never make up for all the humiliation they suffered, all the torture, when I spent time in (Mansfield),” Brown said. “But I promised them, when I got out of there I would never go back. If I didn’t make it in life, it would not be because I didn’t try. You know, you can do bad things in a big city and nobody ever knows about them. But do something wrong in a small town [Crestline’s population was 6,000] and everybody knows. That’s why I was so happy we won it all. I could finally give them something else to talk about.”12

In 2009 Crestline honored Brown by naming its high school baseball diamond Gates Brown Field. He said, “You dream about something like this, but you don’t ever think it’s going to happen. I didn’t want no fanfare when I was with the Tigers, but this is quite an honor.”13

In his 13 years as a player with Detroit, Brown was a part of nine winning ballclubs. He was part of seven more as a coach. Most Tigers fans will tell you that, despite his reserve role, Brown was a huge part of the successful era in Motown. His ability to come through in the clutch has not been matched in the AL. His .370 average in ’68 was the eighth-best season ever for a pinch-hitter. He had 107 pinch hits in his career, the most ever in the American League. He also still holds the AL records for pinch-hit at-bats (414) and home runs (16). Talking about his records in pinch-hitting, he once told a reporter, “Well, one thing, I didn’t do a lot of playing or I wouldn’t have been pinch-hitting.”14

But it wasn’t just with his bat, but with his attitude, that Brown became so successful on the diamond. He was everyone’s favorite teammate. He was a huge crowd favorite. He was an underdog who went from prisoner to champion.

Brown suffered from diabetes and a bad heart, dying at age 74 on September 27, 2013, at a nursing home in Detroit.15 He and Norma had four children: Pamela, Rebekah, Lindsey, and William.

“It’s just a shame,” former manager Jim Leyland said. “We knew his health wasn’t good. To this day, a lot of people think maybe Gates Brown is maybe the best pinch-hitter of all time. Hopefully Gates is in a better place.”16

Acknowledgments

This biography originally appeared in a SABR publication: Mark Pattison and David Raglin, eds., Sock It to ’Em, Tigers (Hanover, Massachusetts: Maple Street Press, 2008). It has been brought up to date with additional research and writing by Bill Nowlin and David Raglin.

Sources

Brown’s quotes about being hounded by Southern fans while in the minors: Rich Koster article, St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 19, 1968.

Joe Garagiola interview information and quotes: Detroit Tigers press release, July 1, 1974.

Poker story with McLain and Northrup and quotes: Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia, 99.

Reference to Mayo Smith receiving letters to start Gates at shortstop during the World Series: Rich Koster article, St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 19, 1968.

Notes

1 Detroit Tigers press release, August 18, 1978. See Gates Brown player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. See also Dave Kindred, “Baseball’s Comic Relief,” The Sporting News, April 25. 1994.

2 Associated Press, “‘On Track’ Gates Shows Youngsters Straight Path,” Bakersfield Californian, July 7, 1942: 42.

3 Brown later said, “He was in love with baseball and knew a few scouts, and he paved the way for them to come in and see me. … Other than that, I don’t know where I’d be today.” George Sipple, “Ex-Tiger Brown to Be Inducted, Twice.” Detroit Free Press, November 1, 2009, found in Brown’s Hall of Fame player file.

4 Rich Koster, “Gates Brown – Hero in Detroit,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1968: 8.

5 Associated Press, “Gates Brown Not Forgetting Past,” High Point (North Carolina) Enterprise, July 7, 1974: 42.

6 Joe Falls, “Gates Brown’s Life an Example for LeFlore,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1975: 18.

7 Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia, 99.

8 Rich Koster, “Gates Brown – Hero in Detroit.”

9Jim Hawkins, “Gates Picking Up Rust as Tiger Spot Swinger,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1974: 23.

10 David Shepardson, “Trial Begins for Former Tiger,” Detroit News, undated article in Brown’s Hall of Fame player file.

11 Mike Brudenell, “Parrish, Six Others Enter Hall of Fame,” Detroit Free Press, April 18, 2002.

12 Joe Falls column, The Sporting News, March 22, 1969: 2.

13 Jon Spencer, “Crestline Goes to Bat for Brown,” Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal, March 17, 2009: 9.

14 William Yardley, “Gates Brown, Tigers’ Clutch Pinch-Hitter, Is Dead at 74,” New York Times, September 28, 2013.

15 Terry Foster, “Tigers Family Mourns Pinch-Hitting Legend Gates Brown,” Detroit News, September 27, 2013.

16 Brendan Savage, “The Complicated Story of Gates Brown, the MOST CLUTCH HITTER on the 1968 Tigers,” MLive, August 2, 2018. https://www.mlive.com/tigers/2018/08/not_all_memories_were_good_one.html. Accessed August 6, 2024.

Full Name

William James Brown

Born

May 2, 1939 at Crestline, OH (USA)

Died

September 27, 2013 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.