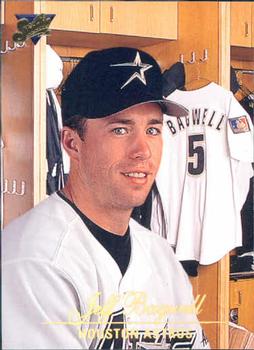

Jeff Bagwell

Jeff Bagwell was a dominant player in the National League for most of his 15-year career. Eight seasons he drove in more than 100 runs. Nine times he hit 31 or more home runs and scored over 100 runs. In 1994 he was unanimously selected as the Most Valuable Player. Despite these and other accomplishments, Bagwell’s career was shadowed by controversy because he played during the steroid era and his reputation, justified or not, marred by that juxtaposition of timing.1

Many felt this issue played a substantial role in his being delayed selection to the Hall of Fame during his first six years of eligibility. While conclusive evidence never surfaced that Bagwell used steroids, his reputation seemed to rest with the concept of inductive reasoning expressed by the old phrase, “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.” His election to the Hall in 2017 went a long way toward dissipating the cloud over his reputation.

Jeffery Robert Bagwell was born in Boston, Massachusetts on May 27, 1968, the only child of Robert and Janice Bagwell. Baseball entered his life early: His father had pitched in college at Northwestern University and subsequently on a semiprofessional basis.2 Janice, who eventually became a police officer, played softball into her 20s. She later recalled that Jeff “could throw a ball before he could walk. When he was six months old, we’d throw a ball to him and he would throw it back.”

Bagwell attended Xavier High School in Middletown, Connecticut, and although playing shortstop for the school, his main sport was soccer. Soccer notwithstanding, he received a baseball scholarship to attend the University of Hartford and came under the tutelage of coach Bill Denehy. Denehy, a former major league pitcher, soon realized Bagwell’s potential, converting him into a third baseman that quickly became a team star.3

While Bagwell performed well for Hartford, he thought major league scouts noticed his playing summer ball. He recalled, “I got my chance in the Cape Cod League. … A lot of players from the best programs in the summer came to play there. Albert Belle was playing there. Frank Thomas. I only hit about .205 that year, but I looked at those guys and decided I could play with them.” Next year he hit over .300, and Boston selected him in the fourth round of the 1989 amateur draft.4

Assigned to the Class A Winter Haven Red Sox in the Florida State League he batted .310, exhibiting little of his eventual power, collecting just two home runs. His performance still earned him promotion to New Britain, the Red Sox Class AA team in the Eastern League. There Bagwell hit .333 to win the batting title and was named the league’s MVP. Again, he generated little power with only four home runs on the year.

As the season ended, word came out of Boston on August 30, 1990, that the 22-year-old Bagwell had been traded to the Houston Astros for Larry Andersen, a 37-year-old relief pitcher. It was then and still is, considered one of the worst trades in baseball history. Red Sox General Manager Lou Gorman, who received the bulk of criticism for this transaction, spent many of his ensuing years explaining his reasons for trading Bagwell.

In a tight pennant race as the 1990 season entered its final month, Boston needed bullpen help badly after their best reliever Jeff Reardon was lost for several weeks due to surgery. Andersen looked like the best potential available help, but Houston wanted a minor league prospect in return.

Bagwell had shown potential at third, but he was at the end of the queue for the position in Red Sox system. Gorman felt he could fill a yawning hole for Boston to “win now” without much sacrifice.5 Years later, Bagwell commented on the trade from his perspective. ”The Red Sox were in a pennant race. They needed help. I was third on their chart at third base. They had Wade Boggs. They had Scott Cooper at Pawtucket. You look at that, and you look at their situation—they bring in free agents all the time.”

At the time, the trade devastated Bagwell: ”I was one of the saddest guys you’ll ever see. All my life everything had been Boston. I was born in Boston. My father was from Watertown; my mother was from Newton, both outside Boston. … our house was one of those places where you couldn’t mention the word Yankees. … Every weekend the television would be tuned to … [t]he Red Sox. No other games. My grandmother Alice Hare, she’s 81 years old, she still lives in Newton, and she can tell you anything … about the Red Sox. I called her to tell her the news. She started crying.”6

Andersen pitched well the last month of the season. In 15 games he posted a 1.23 ERA helping Boston to secure a division championship. As a free agent during the winter, he eventually signed with the San Diego Padres. Those 15 games do not begin to match against Bagwell’s spectacular career with Houston.7

Although he no longer had to compete against Cooper or Boggs, Bagwell still had to contend with Ken Caminiti, well entrenched at third for the Astros. Bagwell came to spring training expecting to be assigned to Houston’s farm club in Tucson. But his play so impressed the Astros that two weeks before the season opener, Houston decided to bring him to the majors—as a first baseman. Bagwell went through a crash course learning how to play the position. In the time remaining until Opening Day he manned first in minor league games during the morning and for the Astros in the afternoon. The Sporting News put it succinctly: “Rookie Jeff Bagwell never played first base before this spring, but the position is his to lose. It’s up to his bat.”8

But that put him in a tenuous position, because Bagwell started slowly, hitting just .100 early in the season. But when he came up to bat in a tie game against the Braves, his first major league home run won the game. The next day he homered again. By the end of April his average had improved to a more respectable .254. And he continued to hit well, finishing the year at .294 with 15 home runs and 82 RBIs, winning the Rookie of the Year Award in a romp with23 of the 24 first place votes.9

Bagwell’s power numbers surprised baseball observers. During his two Double A minor league seasons, he hit six home runs in 932 at bats—or one for every 155 at bats. His 15 home runs for Houston came at the rate of one every 36.9 at bats. Bagwell’s home run total was all the more impressive for having been amassed in the cavernous Astrodome. He also exhibited unique plate discipline for a rookie, gathering 75 walks, 10th in the league. This contributed to a .387 OBP, fifth in the league. Both his power and patience at the plate would improve over the years, each becoming a signature part of his game.

Houston finished last in the NL West in 1991 at 65-97, tying a franchise record for futility. Since winning the division championship in 1986, they had descended into consistent mediocrity. In place of such departed luminaries as Jose Cruz, Glenn Davis and Nolan Ryan, Craig Biggio and Bagwell were coming on board. And they would anchor a team that made the 1990s the most successful decade in Houston’s franchise history.

While the season had not been successful for Houston, Bagwell immediately sensed a key difference from the minor leagues. ”I’ll tell you what made the greatest impression on me during the whole year. We were in Atlanta when the Braves clinched the pennant. We’d played them early in the season, and maybe 10,000 people were at the game . . . at the end of the season, the place was filled every night. All these people were singing and cheering, celebrating. It made you think. You play in the minor leagues and it’s all individual, really. . . . everybody is always looking up, trying to figure where he’s going to go next.” In “major league baseball [, t]he individual didn’t matter. Winning mattered. I watched the Braves, and everything came into focus for me: This is what I want for us.”10

Bagwell successfully avoided the sophomore jinx in 1992. Playing in all 162 scheduled games, his home run total increased to 18.While his average dipped to .273, a careful review of his performance indicated a more disciplined hitter. Strikeouts decreased from 116 to 97 and walks increased to 84, seventh in the league. Part of Bagwell’s success may well have involved his unique batting stance.

Numerous unusual batting styles pepper baseball’s history. Mel Ott’s lifting his right leg, a “foot-in-the-bucket” stance as he began his swing or Stan Musial’s “peeking around the corner” approach come distinctly to mind.11 Bagwell’s was equally unique. It has been described as a “crouching-tiger, hidden dragon” batting stance or more indelicately, “like he is sitting on the john.” He stood in the batter’s box with his legs spread wider than his shoulders in an exaggerated crouch.12With his bottom hand over the knob of the bat, he lifted his left foot a few inches and unleashed a forceful uppercut swing. “That wide stance keeps him from over striding,” Joe Torre observed, “which can be your biggest problem when you’re trying to hit for power.” Despite his odd stance, Bagwell still hit with authority.13 And as unorthodox as his stance appeared, it served another purpose, minimizing Bagwell’s strike zone, a factor in his ability to coax a walk.

His unique stance caused Bagwell repeated injuries three consecutive seasons beginning in 1993. That year he began to come into his own. Batting .320 with 20 home runs and 88 RBIs in mid-September, Bagwell broke his hand on a pitch from the Phils’ Ben Rivera. His next two seasons ended prematurely for the same reason. An examination of his swing indicated Bagwell’s hands dipped into the strike zone making them vulnerable to injury. After his third broken hand in 1995, he began wearing a protective pad over his batting glove.14

While the season ended early for Bagwell, it marked Houston’s steady improvement. After having finished last in 1991, the Astros progressed to fourth in 1992 and third in 1993. Bagwell as well as players like Craig Biggio, Caminiti, and Luis Gonzalez were improving. Pitcher Daryl Kile blossomed in 1993 going 15-8. In the strike-shortened 1994 season, both Bagwell and the Astros improved markedly.

In just 400 at bats, Bagwell scored 104 runs and drove in a league-leading116.He hit .368, second behind Tony Gwynn’s .394, but what really caught everyone’s breath was his .750 slugging percentage. At the time it ranked seventh highest all-time in a season, second best in the NL, just behind Rogers Hornsby’s .756 in 1925. On June 24, he hit three home runs in a game against the Dodgers, two coming in the sixth inning. Indeed, between May 16 and July 24 Bagwell hit two or more home runs in a game five times. “Crazy stuff happened that year,” Bagwell recalled. “Every pitch that I was looking for, I got. And when I got it, I didn’t miss it. It was ridiculous.”15Lost amidst Bagwell’s hitting exploits was his receiving the NL Gold Glove Award at first base, a testament to his well-rounded abilities.

In just 400 at bats, Bagwell scored 104 runs and drove in a league-leading116.He hit .368, second behind Tony Gwynn’s .394, but what really caught everyone’s breath was his .750 slugging percentage. At the time it ranked seventh highest all-time in a season, second best in the NL, just behind Rogers Hornsby’s .756 in 1925. On June 24, he hit three home runs in a game against the Dodgers, two coming in the sixth inning. Indeed, between May 16 and July 24 Bagwell hit two or more home runs in a game five times. “Crazy stuff happened that year,” Bagwell recalled. “Every pitch that I was looking for, I got. And when I got it, I didn’t miss it. It was ridiculous.”15Lost amidst Bagwell’s hitting exploits was his receiving the NL Gold Glove Award at first base, a testament to his well-rounded abilities.

Unfortunately, the 1994 season ended when players went on strike in mid-August due to acrimonious disputes with team owners over several issues. Houston trailed Cincinnati by half a game when the strike took effect. Whether the Astros could have continued to hold their own in the race was problematic though. Because the day before the strike commenced, Bagwell was hit by a pitch from San Diego’s Andy Benes that broke the fourth metacarpal on his left hand, the same bone he broke a year earlier. “I can’t believe this happened to me two years in a row” he said after X-rays confirmed he would be out several weeks—essentially until the end of the season.16 But a day later the season ended anyway. Paradoxically, timing of the strike benefitted Bagwell in ways unforeseen at the time.

Despite the truncated season, players were still selected to receive individual awards. The BBWAA unanimously choose Bagwell as the National League’s MVP. He was only the 11th player and fourth National Leaguer to win every writer’s first place votes. “It’s very flattering. It means more to me than you can possibly imagine.”17

Strong conjecture had it that if the season had continued with Bagwell sidelined the award might have gone elsewhere. Matt Williams of the San Francisco Giants who finished second in the MVP voting had 43 home runs when the strike started and on a pace to hit over 60. With the Giants in the thick of the pennant race he could well have supplanted Bagwell in the voting. Bagwell did win the award however, the first and only Astro through 2014 to do so. Despite his spectacular year however, Bagwell’s achievement is always less lustrous because it happened in the “strike shortened season.”

Once play resumed in 1995, Houston was expected to contend as they had in 1994. Bagwell and Biggio began dominating the Astros’ offense, and within a year they gained nickname, “The Killer B’s.” Over the years other “B’s”—Derek Bell, Carlos Beltran, and Lance Berkman—came to prominence, but Bagwell and Biggio remained constants.

The team performed well; on July 30 they were just 3½ games behind the Reds when Bagwell was hit on his left hand by San Diego’s Brian Williams, taking him out of the lineup for several weeks. “I was getting it X-rayed and I was moving it pretty good,” said a frustrated Bagwell. “I thought, O.K. it’s probably going to be O.K. That’s the same thing I said last year, and that’s the same result. I don’t know whether to change my stance. I’ve taken all the precautions.”18 Of the pennant race, he noted: “I can’t tell you how sad I am about this right now because . . .we’re playing great baseball. We’ve still got a great team and everything, but I know my production was helping, at least.”19 From then on a special pad protected Bagwell’s batting glove, and he never suffered this injury again.

Bagwell proved prescient. The team had gone 9-21 in his absence and was 13½ games behind the Reds, well out of the race. He had started the season slowly, hitting just .183 at the end of May, but in the next two months he had improved to .283 and was on a batting spree. Bagwell finished at .290 with 21 home runs. A fall off from 1994, but he would more than make up for it the next several seasons as his and the Astros’ potential came to full fruition.

Bagwell undertook a rigorous training program after the 1995 season. He gained 20 pounds and enhanced his endurance for the rigors of grueling seasons by a concentrated period of weight lifting, change of diet, plus the use of creatine and androstenedione.20 In later years those entering the Astro’s gym were welcomed by a banner reading, “Bagwell’s Gym. Work Hard. Play Hard. Or Leave,” a testament to his intense work ethic. “It’s pretty impressive when you watch a guy like him,” observed Geoff Blum, a later teammate. He “knows what he has to do, and he puts his mind to it and he does it.”21While successful in the short term, Bagwell later came to feel his regimen shortened his career, that his muscular buildup contributed greatly to shoulder problems forcing his retirement in 2005 at age 37.22

By the start of 1996, Bagwell was one of the senior members on the Astros if not by age then by tenure. He had become a forceful influence on how Houston prepared for games, i.e., with maximum effort and players held accountable for their actions. Discipline fostered camaraderie, and Bagwell made sure everyone on the team was part of the team.23 His and Biggio’s leadership propelled the Astros to new levels of play.

His workout regimen generated tremendous results. The 1996 season began a run of performances that established Bagwell’s reputation as one of the most dominant players of his era. That year he batted .315, hit 31 home runs, drove in 120 runs, and led the league with 48 doubles. It was the first of six consecutive seasons where Bagwell scored and drove in at least 100 runs, averaging 128 runs scored and 126 RBIs per year during this stretch.

Some of the numbers he put up were spectacular. In 1999 Bagwell drew 149 walks (including a major league record six in one game), at the time the third highest single season total in the National League. Twice that year he hit three home runs in one game. The following year he launched a career-high 47 homers and scored 152 runs, fourth highest in the NL since 1900.

Bagwell had become a complete ballplayer. In 1997 he stole 31 bases and hit 43 home runs. In 1999, 30 stolen bases and 42 homers. One of only 13 major league players to have accomplished 30 home runs and steals in a season more than once, Bagwell and Joe Carter remain the only first basemen to reach the 30-30 club through 2014.While Bagwell was at the peak of his career Houston took division championships in 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2001, the best run in franchise history. Of the 13 games played in the four post-season series however, Houston managed but a single 5-4 victory over San Diego in 1998. Unfortunately, in the other three series Houston confronted the Atlanta Braves and their buzz-saw starting rotation of Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux, and John Smoltz. Bagwell’s performance in these series was equally dismal, just .174 with no extra base hits and just four RBIs.

In 2002 and 2003 both Bagwell and his team declined. Houston finished second both years but failed to make postseason competition. Bagwell’s run of 100 RBI seasons ended with 98 in 2002. He achieved an even hundred RBIs in 2003, but his peak-year production had waned. His slugging averages dipped into the low .500s, well below what had become customary for him. Still a strong hitter, at 35 years old he no longer dominated as he once had.

Beginning in 2001 pain began flaring in his left shoulder. He underwent surgery in the offseason to extract bone spurs and restore a torn labrum.24 Eventually he developed arthritis in the other shoulder, an affliction that worsened over time.25 By 2004, his career entered the twilight: Bagwell’s average fell to .266 with “only” 27 home runs and 89 RBIs. His defense suffered too. The first baseman who could whip a ball to third on bunts eventually got to the point where he had trouble merely throwing to infielders between innings.26 Ironically, he had the best post-season of his career in a seven game series that St. Louis ultimately won. Bagwell hit .318 with two home runs, the second helping break open the fifth game.

As the 2005 season began, Bagwell played through April until the pain in his right shoulder became intolerable. On May 4, after going 0-5 in a loss to Pittsburgh he was hitting just .250 with only 3 home runs in 88 at bats. The next day he asked Astros’ manager Phil Garner to be pulled from the lineup. “I couldn’t hit, I couldn’t throw, if I played, I’d just be hurting the team.”27 By September, following shoulder surgery, he was well enough to join an Astros team contending for a wild card spot in the standings. Playing exclusively as a pinch hitter he drove in his last major league run on a ground out against the Cubs, providing an insurance run in a critical 3-1 win. For Houston’s win that day and the next allowed them to finish one game ahead of the Phillies for the wild card position.

The Astros finally beat their longtime nemesis Atlanta Braves to win the Division Series then defeated the Cardinals to win the NL pennant. But the Chicago White Sox swept them in four straight games in the World Series. Bagwell went 1 for 8 as a DH and pinch hitter, just one of many Astros stymied by Chicago’s pitching in a closely played series. Bagwell’s ground out as a pinch hitter in the fourth game proved his last major league appearance.

Bagwell went to spring training in 2006 to see if he could still contribute on the field. But legal issues, specifically who was going to pay Bagwell’s estimated $15.6 million salary for the year, muted Houston’s welcome. The situation was awkward. The Astros had obtained a disability insurance policy on Bagwell when he had signed a multi-year contract in 2001. And at this point the team essentially had to prove that Bagwell became disabled between the end of 2005 and January 31, 2006, when the policy expired. So Bagwell’s appearance in camp threw Houston’s claim that he was disabled into question. Amid the legal maneuvering, it was revealed that a physical examination of Bagwell in January 2006 concluded he could only throw a ball 35 mph, and then only for short distances.28 Based on that assessment, the attending physician declared Bagwell totally disabled.29

Bagwell appeared in a few practice games but had to quit several when his shoulder became too sore to continue. He was hitting just .219, but the major obstacle to continued play remained his arm. He simply could not throw a ball to meet major league standards. The chances of additional surgery succeeding were minimal. The conclusion was obvious.

Bagwell had given it all to come back. “You have to do everything you can to try and play. If not you’ll be kicking yourself.” Houston placed him on the DL, and Bagwell recognized the reality: “I may never play again.”30 He was right. A few months after the 2006 season ended, he officially retired from the game.31 “[I]t’s been a great ride,” he said. “I wish I could still play and try to win a World Series here in Houston but I’m not physically able to do that anymore. I’m OK with that.”32

Bagwell’s lifetime stats are impressive: .297 batting average, 449 home runs, 1,529 RBIs, 79.6 WAR, and .948 OPS. But there was more to Bagwell than robust numbers. He was a role model in the clubhouse, a “consummate professional” who, along with Biggio set the bar for how an Astro approached the game. Houston’s best years remain the heart of the “Killer B” years (1996-2001) during which the Astros won four of six division championships, the finest years of the franchise.

The Astros wanted Bagwell to stay connected with the organization and so signed him to a personal services contract through 2009, mostly to spend time working in player development. Bagwell’s post playing career has been largely low key and private. Although he has had intermittent assignments with the team, Bagwell’s aversion to travel and devotion to his family have been his guiding principles.

He did not totally avoid the limelight however. On June 28, 2007, his longtime teammate and friend Craig Biggio singled against the Colorado Rockies to get his 3,000 hit. Biggio’s family joined him on the field, and he insisted Bagwell come out to be with him as well. It was Bagwell’s first appearance before Houston’s fans since he retired.33 A few months later Houston retired his Number 5 before Bagwell, his family, and more than 42,000 onlookers.

In mid-season 2010, the Astros asked Bagwell to become their batting coach. Last in hitting, the team hoped his expertise and rapport with players could improve their output. Their hitting did improve over what remained of the season, but Bagwell, citing family obligations, turned down a proffered two-year contract to continue the job. “My decision came down to the times that these coaches put in, the effort they put in, and my family.”34 He returned to his personal services agreement occasionally spending time with the club, usually in spring training helping younger players.

In 2011 Bagwell became eligible for induction into the Hall of Fame. More than anything else this has kept his name in the media and before fans over the years. The first year he was eligible he received 41.7 percent of the writer’s votes for induction. Every year since he consistently received over 50 percent of the vote with a high of 59.6 in the 2013 election.

Whether he deserved induction was a controversial subject over the years. Several factors delayed his induction. On a few occasions, most recently in 2015, he was up against a crowded field of worthy candidates, which tended to concentrate votes on first-time eligible players.35 A second and more serious consideration is that Bagwell’s career peaked in the late 1990s coinciding with what has become known as baseball’s steroid era. One of the major side effects of this period was to cast a pall of suspicion over virtually all its players, including high performers like Bagwell.

Several aspects of Bagwell’s career prompted questions about steroid use. Ken Caminiti, one of his teammates and close friend on the Astros, publicly admitted he took steroids during his career, a fact dramatically underscored when he died of a drug overdose at the age of 41, just three years after retiring from the game. For Bagwell it suggested guilt by association.36

His physical growth led to further conjecture. The slim 185-pound minor league third baseman grew to 220 at the peak of his career. Creation of a bodybuilder’s physique and its subsequent reduction in size as a career waned was “typical” of players found to have used steroids—and another factor fueling speculation about Bagwell’s career.37

These perceptions seemed relevant because of the curve of that career. He started out with just six home runs in two minor league seasons and averaged fewer than 20 per year during his first three years in the majors. At the top of his game he had successive seasons of 31, 43, 34, 42, 47 and 39 home runs. Bagwell surged almost simultaneously with Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, two sluggers whose drug use subsequently sullied their career reputations. Their and others’ accomplishments generated questions about the proliferation of home runs hit during this period. It became a centerpiece of suspicion that something might be amiss.38

These sorts of associative considerations fueled speculation that Bagwell used steroids or PEDs. He was never linked to use of drugs, however, either through the drug testing policy, various investigations, or legal actions. Bagwell consistently denied employing drugs or steroids on numerous occasions. But he has come to believe that whatever he says will not matter. In a 2009 interview, Bagwell observed that his is a no-win situation. “I know what I did; I know how hard I worked. If someone thinks I took crap because I was in that era, what am I going to do to show them I didn’t? I can’t go take a blood test now.”39

Bruce Jenkins, Senior Sports Editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, acknowledges that while steroid suspicion was a factor for several voters, there is another point of consideration. “I certainly can’t speak for the bulk of national baseball writers, but I know that many are suspicious of Bagwell—without proof, as you say. I’ve always voted for the best players—Bonds, McGwire, Clemens, etc.—so that’s not a factor for me. I always found Bagwell just a bit short of Hall of Fame material. Heck of a player, I don’t mean to knock him, just my personal opinion. And I do know that some other writers feel that way, as well.”40

Because of the controversy over drugs, Bagwell increasingly showed ambivalence about getting into the Hall because even if elected, it would be an empty accomplishment. Induction into the Hall is not what defines him, “I keep telling people this and people don’t understand it. . . . Baseball does not define me as a person. It’s what I do with my kids, and as a husband, that’s going to define me. It’d be an honor, don’t get me wrong, but I’ve got other things to do in my life too.”42

Amid the discussions, Bagwell went on with his life. Twice divorced, he remarried in August 2014. He and his wife Rachel have five children in their blended family.44 He lives in the Houston area and occasionally works with the Astros, most recently spending several days with them in the spring of 2015 as a special instructor.45

Just when it seemed Bagwell would stay in a Hall of Fame netherworld, a change took place in how players were selected for induction. A rules change in voter eligibility seemed to generate greater support for his induction. Beginning with balloting in 2016, voters were required to have ten years of continuous membership in the Baseball Writers Association of America as well as be active members or been active members in the Association in the ten years prior to balloting. This had a practical effect of removing more than 100 voters from the process, many of whose careers paralleled the steroids era. The elimination of this bloc of voters seemed to signal a more tolerant perspective of players from that time frame.

It was reflected in a change of voter patterns. Mike Piazza, thrice denied induction was selected with the 2016 vote. Players suspected of steroid use such as Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling saw their support increase. Bagwell received 71.6 percent of the vote, missing election by 15 out of the 440 votes counted.

That trend continued for many of these players in 2017, most dramatically for Bagwell who was selected for induction receiving more than 82 percent of the votes, higher than anyone else on the ballot. He was formally inducted into the Hall of Fame on July 30, 2017 surrounded by family, friends, fans – and teammates. Most prominent of these was Craig Biggio.

While Bagwell’s credentials were questioned for years there was never any question how his teammates viewed him. Astros pitcher Mike Hampton once called Bagwell “the ultimate teammate,” in an interview. “Bagwell and Biggio let it be known that there was an Astros way of doing things. The Bagwell and Biggio way was to demand accountability, starting with themselves. Bagwell was particularly quick to deflect credit for his success, explaining ‘that’s my job,’ and to readily accept blame—often for the failures that weren’t even his. His ability to connect with teammates knew no barriers, racial or otherwise.”46

This description, echoed by many, more than any outside voting process reflected the highest compliment a player can receive. It speaks well of a one-time skinny Red Sox prospect who indeed had “a great ride.”

Last revised: August 1, 2017

Notes

1 The author would like to express his appreciation for Mr. Bill Francis at the Baseball Hall of Fame (HoF) who provided a copy of material from Jeff Bagwell’s HoF file for this article and to Tom Schott for his editorial skills in improving this piece.

2 Bill Ryan, “Sergeant, Mom, Her Dream is Still Fenway Park”, Bill Ryan, New York Times, August 28, 1994, A1.

3 Ibid.

4 Leigh Montville, “Trade Deficit Jeff Bagwell Has Proved by Trading him to the Astros, the Red Sox Made a Ruthian Blunder,” Sports Illustrated, Vol. 79, No. 4, July 26, 1993: 44-48.

5 Lou Gorman, One Pitch From Glory: One Decade of Running the Red Sox, (Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing L.L.C., 2005), 137-39.

6 Montville, “Trade Deficit Jeff Bagwell.”

7 See, for example, “The List: Readers Pick Most Lopsided Trades,” http://espn.go.com/page2/s/readers/worstdeals.html

8 “Rolling the Dice,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1991, 10.

9 Pittsburgh first baseman Orlando Merced received the other first place vote.

10 Montville, “Trade Deficit Jeff Bagwell.”

11 See Alfred M. Martin, Mel Ott, The Gentle Giant, (Lanham MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2003), 23-25, and James M. Giglio,Musial: From Stash to Stan The Man, (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001), xi.

12 Steve Campbell, “Jeff Bagwell knows he did things the right way in a Cooperstown-worthy career. But if the Hall doesn’t call the former Killer B? ‘I’m good’ he says,” Houston Chronicle clipping, July 28, 2009. Bagwell’s HoF file; Tom Verducci, “One of a Kind – A self made slugger with a screwy stance,” Sports Illustrated, Vol. 91, No. 3, July 19, 1999: 56-61.

13 Tim Windal, “The Swing is the Thing,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, July 27-August 2, 1994, 36.

14Verducci, “One of a Kind.”

15 Ibid.

16“Benes Pitch Breaks Bagwell’s Hand,” The Washington Post, August 11, 1994, D4.

17 Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., “Bagwell’s Latest Stat: All the M.V.P. Votes, New York Times, October 28, 1994, B13.

18 Murray Chass, “Different Departures for Bagwell and Kruk,” ibid., July 31, 1995, C3.

19 “Astros Lose Games but lose Bagwell,” The Washington Post, July 31, 1995, B7.

20Verducci, “One of a Kind.”

21 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Bagwell turns to weight room to regain shoulder strength,” Houston Chronicle, November 26, 2002.Bagwell’s HoF file.

22 Jerry Crasnick, “Jeff Bagwell Tires of Steroid Talk,” ESPN.com, December 29, 2010,http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/hof11/columns/story?columnist=crasnick_jerry&id=5963276.

23 See, for example, Campbell’s “Jeff Bagwell knows he did things the right way in a Cooperstown-worthy career. But if the Hall doesn’t call the former Killer B?” and John Smith, “Stats alone no measure of this man,” Houston Chronicle, December 16, 2006, sports section, 1.

24 Ortiz, “Bagwell turns to weight room.”

25 Richard Justice, “Bagwell reaches limit of pain,” Houston Chronicle clipping, May 10, 2005, from Bagwell’s HoF file.

26 ESPN.com News Service, “Bagwell acknowledges he might ever play again,” March 26, 2006.

27 Richard Justice, “Bagwell reaches limit of pain,” Houston Chronicle clipping, May 10, 2005, Bagwell’s HoF file.

28 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Bagwell insurance claim denied,” Houston Chronicle clipping, March 28, 2006 from Bagwell’s HoF file.

29 The Houston Astros and Connecticut General would eventually settle the matter in a confidential agreement in December 2006. See Brian McTaggart, “Insurance Settlement Reached,” Houston Chronicle, December 2006, from Bagwell’s HoF file.

30 Jason Stark, “Bagwell acknowledges he might never play again.’” ESPN.com News Service, March 26, 2006.

31 A private settlement was reached on the Astro’s insurance claim in December 2006. Alyson Footer, “Report: Astros settle insurance claim,” MLB.com, December 15, 2006.

32 Brian McTaggart, “Bagwell retires, remembers ‘great ride,’” Houston Chronicle clipping, December 2006,Bagwell’s HoF file.

33 “Biggio Gets His 3,000 Hit in Houston,” New York Times, June 29, 2007, D4.

34 Zachary Levine, “Bagwell cites family reasons,” Houston Chronicle clipping, October 28, 2010, Bagwell’s HoF file.

35The 2015 HoF selectees were: Bagwell’s teammate Craig Biggio, Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, and John Smoltz.

36 See for example Asher B. Chancey, “The Bagwell Conspiracy,”http://baseballevolution.com/asher/bagwellconspiracy.html or Harold Friend, “Jeff Bagwell is Guilty Until Proven Innocent,” April 20, 2012,http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1153441-jeff-bagwell-is-guilty-until-proved-innocent-of-steroid-use or Adam Spolane, “If Frank Thomas is a Hall of Famer Jeff Bagwell Should Be Too, January 8, 2014,http://houston.cbslocal.com/2014/01/08/if-frank-thomas-is-a-hall-of-famer-jeff-bagwell-should-be-too/ for several online articles concerning Bagwell and Caminiti.

37 See http://houston.cbslocal.com/2014/01/08/if-frank-thomas-is-a-hall-of-famer-jeff-bagwell-should-be-too/ and Richard Justice, “Steroids? Not me, says Bagwell,” Houston Chronicle clipping, February 25, 2004,Bagwell’sHoF file.

38 One measure of this phenomenon: In the 1980s, just 13 major leaguers hit 40 or more home runs in a season. In the 1990s, 71 players did it, and more than 60 homers in a season happened four times. During the previous 90-plus years only Babe Ruth (in 1927) and Maris (in 1961) achieved this mark.

39 Steve Campbell, ‘B’ all, end Hall?” Houston Chronicle, July 28, 2009 from Bagwell’s HoF file.

40 Email, Bruce Jenkins to author, July 19, 2015.

41 For a dissenting view to Jenkins’, see Dayn Perry, “Hall of Fame candidate breakdown: Jeff Bagwell,” August 27, 2015, http://www.cbssports.com/mlb/eye-on-baseball/24906915/hall-of-fame-candidate-breakdown-jeff-bagwell.

42 Ted Berg, “New Astros instructor Jeff Bagwell on his Hall of Fame case: “I don’t expect to get in,” USA Sports Today, March 10, 2015, http://ftw.usatoday.com/2015/03/jeff-bagwell-houston-astros-hall-of-fame-spring-training-instructor-mlb.

43 Jerry Crasnick, “Jeff Bagwell Tires of Steroid Talk,” ESPN.com, December 29, 2010.http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/hof11/columns/story?id=5963276

44 The author wishes to thank Bob Dorrill of the SABR Houston/Larry Dierker Chapter for information on Bagwell’s post-career life.

45Evan Drellich, “Jeff Bagwell takes small step back into baseball with the Astros,” March 10, 2015, http://blog.chron.com/ultimateastros/2015/03/10/jeff-bagwell-takes-small-step-back-into-baseball-with-astros/#30721101=0

46 Steve Campbell, ‘B’ all, end Hall?” For others’ views on Bagwell, see Richard Justice, “Astros retire Bagwell’s No. 5,”Houston Chronicle, August 26, 2007, and Tom Haudricourt, “Biggio, Bagwell finally there,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Oct. 20, 2005.

Full Name

Jeffrey Robert Bagwell

Born

May 27, 1968 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.