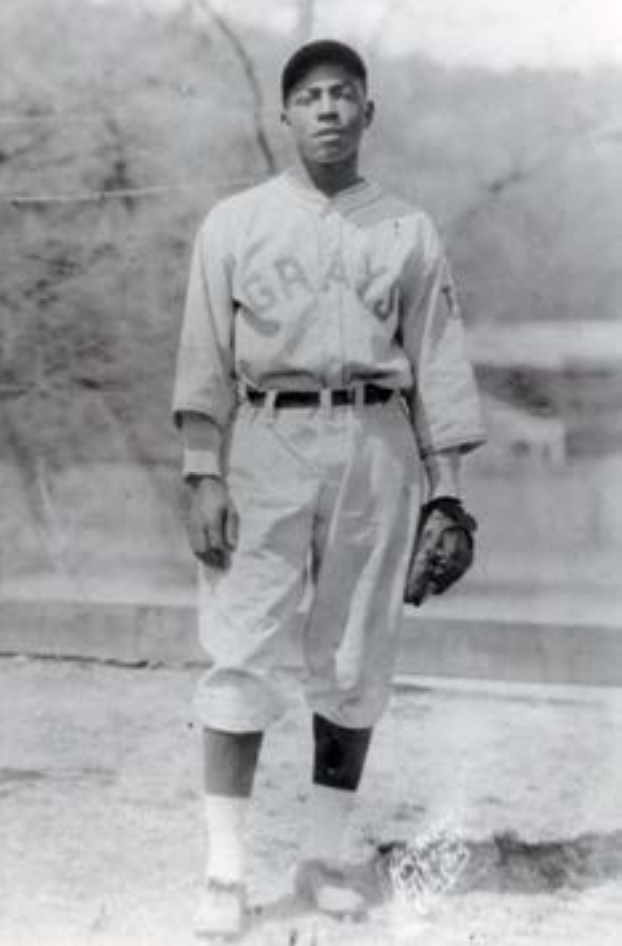

Vic Harris

The Homestead Grays were a dominant force in Negro League baseball from 1926 to 1948. While the faces and muscles of this franchise were Hall of Famers Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard, the heart and soul of the Homestead Grays was feisty player-manager Vic Harris, who was known and admired by teammates and opponents alike for his fierce style of play.

The Homestead Grays were a dominant force in Negro League baseball from 1926 to 1948. While the faces and muscles of this franchise were Hall of Famers Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard, the heart and soul of the Homestead Grays was feisty player-manager Vic Harris, who was known and admired by teammates and opponents alike for his fierce style of play.

Longtime teammate Buck Leonard said of Harris’s baserunning style, “He just undressed the opposing infielder – cut the uniform right off his back.”1 Second baseman Dick Seay agreed. “He would cut you in a minute. Cut you and laugh.”2

Harris earned the nickname Vicious Vic for his reputation for violent behavior, both on and off the field.3 Harris and teammates Jud Wilson, Oscar Charleston, and Chippy Britt composed a group that became known as “the four big, bad men of black baseball.”4

Elander Victor Harris was born to William and Frances Harris in Pensacola, Florida, on June 10, 1905. His father was a farmer.5 Two of his brothers, Bill and Neal, would also play Negro League baseball. He moved with his family to Pittsburgh when he was “nine or ten years old”6 and soon started to play baseball in with the YMCA team. William Harris brought his family from the agrarian South to the industrial North. Many African American families moved North to find better economic opportunities in the first decades of the twentieth century in a movement known as the great migration. William Harris found a job as a scrap man at a steel factory.7 Vic Harris attended Pittsburgh’s Schenley High School from 1919 to 1922.8

Harris caught the eye of Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey, who approached him in 1923 about playing for his team, but Harris joined the Cleveland Tate Stars instead.9 In his first season in professional baseball, Harris hit .297 as an 18-year-old starting outfielder.

The next year, Harris jumped from the Tate Stars to the Cleveland Browns. As a Brown, Harris hit .229 in 27 games and was second on the team with 14 RBIs. He jumped the Browns to take advantage of the opportunity to play for Negro League pioneer and legend Rube Foster and his Chicago American Giants. In his final 10 games of the 1924 season with Chicago, Harris hit .257. There is no doubt that Foster’s leadership style had an impact on the manner by which Harris would later compile his own legendary numbers as a manager.

In 1925, Harris began his long-term service for the Homestead Grays. He recalled, “I stayed with Posey for the rest of my career, except for one year – 1934. That’s the year I played with Gus Greenlee and the Pittsburgh Crawfords.”10 That “rest of my career” would last 22 years with the Homestead Grays as a player, and from 1935 to 1948 as a player-manager. The only years in which Harris was not associated with the Grays were the 1934 season he spent with the crosstown rival Crawfords and 1943, when he took a job at a defense plant during World War II.11 Limited records from the 1925 season show Harris hitting .250 (1-for-4) in his first season with the Grays.12

Negro League records are scarce for Harris’s first few seasons with the Grays. Available statistics show him batting .500 (3-for-6) for 1926, but no statistics for 1927 are to be had. Harris hit .333 for the Grays in 1928. By this time, he had entrenched himself at the top of the Grays lineup, usually batting first or second.13 Harris was a contact, spray hitter, and this quality made him a good hit-and-run man batting behind a leadoff batter. In 1929 Harris hit a steady .286 for the Grays in 140 at-bats.

The 1930 season was a breakout campaign for Harris. He hit .338, which was third on the team in average, finished second on the team in home runs, and was third in RBIs.

Harris’s average dipped to .273 for the 1931 Homestead Grays, a team that notched its place in baseball history via a 143-29-2 record against all levels of competition.14 Catcher-pitcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe called this team the greatest baseball team of all time, and recalled that the team won 35 games before it suffered its first loss.15 Baseball scholars have debated whether the 1931 Homestead Grays, 1925 Kansas City Monarchs, or 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords were the greatest single-season team in Negro League history. More broad-thinking scholars include the 1931 Grays with the 1927 New York Yankees in their discussions of the greatest baseball team of all time. The 1931 Homestead Grays included future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Jud Wilson, Oscar Charleston, Willie Foster, and Smokey Joe Williams. The team also included perennial all-stars George Scales, Ted Page, and Double Duty Radcliffe. Harris started and played left field on this great team. With the Great Depression raging, Negro baseball took quite an economic hit. As a result, the 1931 Grays were not affiliated with any league. They were strictly a barnstorming team, which meant that this outstanding lineup did not even have the opportunity to claim a pennant or championship.

In 1932 Homestead joined the East-West League. That year’s squad was the first Grays team to win a league championship as it recorded a .614 winning percentage to claim the league pennant. Harris hit .333, but the team was so strong that his average was good enough for just fourth on the team.

Harris followed his solid 1932 season by hitting .311 for Homestead in 1933, the first of seven seasons in which he would be selected to participate in the East-West All-Star Game. The annual game was played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park (some years a second game was played elsewhere as well) and was the highlight and showcase of every Negro League season. Harris was also named to the East-West Classic in 1934, 1938, 1939, 1942, 1943, and 1947.16

The city of Pittsburgh was embroiled in a baseball civil war between Cum Posey of the Homestead Grays and Gus Greenlee of the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Harris left the Grays for the Crawfords for the 1934 season, though he was not the only one. Several Grays jumped to the Crawfords during its eight-year existence in Pittsburgh. Harris hit .339 for the Craws in 1934, which led a team that was stocked with both future Hall of Famers (Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, Cool Papa Bell, and Satchel Paige) and East-West All-Stars (Rap Dixon, Jimmie Crutchfield, Sam Streeter, and Leroy Matlock among them).

Harris was lured back across town for the 1935 season by an offer he could not refuse. “I went back to the Grays,” he recalled, “and Posey made me manager. He had been managing the team until then. He was fiery, and he knew I was fiery, so he made me manager.”17 Harris’s first managerial assignment began a career of 15 extremely productive years as a manager and coach. Harris hit .326 and tied for the team lead in home runs for 1935, the season in which he also was selected to his second East-West All-Star team. The Grays recorded a only a 25-35-2 record (.417) in Harris’s first season at the helm, but it would be 11 more years before the Homestead Grays had another sub-.500 winning percentage for a season. That winter he played in Puerto Rico for San Juan.

Harris enjoyed a banner year in 1936. Not only did he lead the Grays in batting with a .351 average, but that offseason – on October 14, 1936 – Harris married Dorothy Smith, the woman who would remain by his side until the day he died. After the season Harris also tried his hand at managing in winter ball. For the years 1936-1939, he managed a barnstorming team in the continental United States.18 He went farther south from 1947 to 1950 to manage Santurce in the Puerto Rican League, where he recorded three straight winning seasons.

The 1937 Negro League season began an unprecedented run of success for the Homestead Grays. From that year through 1945, the Grays won nine consecutive league championships, a record that has never been equaled at any level of professional baseball. Harris did not manage during the 1943 and 1944 seasons because of his work in the defense factory. Negro League legend Candy Jim Taylor was the full-time manager while Harris was doing his bit for the war effort. For those championship years, Harris hit .315 in 1937; .327 in 1938; .264 in 1939; .269 in 1940; .248 in 1941; .264 in 1942; .348 in 1943; .500 in 1944 (10 at-bats); and .333 in 1945 (nine at-bats).

In 1941 Harris was named as a manager for the first time in the East-West Classic, an honor that would again be bestowed upon him in 1942, 1943, 1945, 1946, and 1948. In all, Harris recorded a 4-4 record as a manager in the Classic.19 His eight games as a manager were twice as many as the runner-up, Oscar Charleston.20

Harris came back to the Grays full-time as a manager in 1946. After two sub-.500 seasons in 1946 and 1947, Harris led his 1948 team, a member franchise of the Negro National League, to another pennant, and a 4-games-to-1 victory over the Negro American League’s Birmingham Black Barons in the final Negro League World Series.

The NNL disbanded after the 1948 season and the Grays became a member of the Negro American Association, a Black minor league, in 1949. By then Negro League baseball teams were losing their best players to the major leagues after Jackie Robinson made it big with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Harris had foreseen such a fate for the Negro Leagues in 1942, when the integration of major-league baseball had become a hot topic after Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher asserted that he would use Black players if only the major-league owners and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis would allow it. Harris had predicted, “If they take our best boys, we will be but a hollow shell of what we are today.”21

Harris voiced doubts about whether the integration of Organized Baseball would be a positive development for Black ballplayers, saying, “[It] might be a good thing and then again, it might not be.”22 He knew that not every Black ballplayer would have a shot at the majors and wondered how the other 75 to 80 percent of Negro League players would survive.23 Integration had come to pass, however, and Harris’s prophecy about its effects on the Negro Leagues was in the process of being fulfilled. Harris signed on as a coach for the Baltimore Elite Giants in 1949. He became the skipper of the Birmingham Black Barons in 1950, and posted a 52-25 record in what was his final season as a manager.

Harris retired from professional baseball after the 1950 season. In his retirement, he was the head custodian for the Castaic Union Schools in Castaic, California. He died on February 23, 1978, after an unsuccessful second operation to rid him of cancer.24 He was survived by Dorothy, his wife of 36 years; a daughter, Judith Victoria Harris; and a son, Ronald Victor Harris.

In evaluating Vic Harris’s 27-year career in baseball, several statistics stand out above his peers. On one of the greatest teams of all time, the Homestead Grays, Harris finished his playing career in the top seven of 14 different offensive categories. He finished first on the Grays’ all-time list for games played, at-bats, hits, triples, and hit batsmen. He finished second in runs scored, doubles, and bases on balls. He is third on the Grays’ list of home runs and runs batted in, fifth in sacrifice hits, sixth in batting average and slugging percentage, and seventh in stolen bases. Add Harris’s lifetime .303 batting average,25 and it is enough to make a person wonder why the National Baseball Hall of Fame has not enshrined him yet.

As impressive as Harris’s lifetime totals are as a player, his record as a manager is even more extraordinary. Harris is first on the Grays’ list of games won as a manager. His teams won more Negro League titles – eight – than any other manager; the next closest competitors (Candy Jim Taylor, Dick Lundy, Frank Warfield, Dave Malarcher, Rube Foster, and José Mendez) have three titles each.26 His lifetime managerial record in the Negro leagues, All-Star games, postseason, and winter leagues stands at 754-352, a .682 winning percentage.27 Harris was not only the greatest Negro League manager of all times, it can be argued that he may well have been the greatest manager in the history of baseball. If Cooperstown cannot use him in its outfield, surely it can use him as a dugout strategist.

Whether or not Harris was the greatest manager of all time, one thing is certain: He was the manager of the reigning and defending Negro League World Series champion Homestead Grays, a title he is guaranteed to keep since there never was another Negro League World Series after 1948.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, the Seamheads.com Negro League Database, the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, and the following:

Clark, Dick, and Larry Lester, eds. The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994).

Hogan, Lawrence D. Shades of Glory (Washington: National Geographic, 2006).

Johnson, Earl. “Sports Whirl,” n.d.

Lester, Larry, and Sammy J. Miller. Black America Series: Black Baseball in Pittsburgh (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

“Obituaries,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1978.

Photo credit: Vic Harris, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Vic Harris and John Holway, “Baseball Old Timers: Vic Harris Managed the Homestead Grays,” Dawn Magazine, March 8, 1975: 12.

2 Harris and Holway.

3 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 360.

4 Karen and Kevin Flynn, “Remembering Vic Harris,” DCBaseballHistory.com, https://dcbaseballhistory.com/2013/08/remembering-vic-harris/

5 1910 US Census.

6 Harris and Holway, 13.

7 1920 US Census.

8 Merl F. Kleinknecht, “Vic Harris,” in David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports(Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000).

9 Harris and Holway, 13.

10 Harris and Holway, 13.

11 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003), 258.

12 baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=harris002vic. This appears to reflect incomplete statistics.

13 Riley, 360.

14 Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles Great Teams: The 1931 Homestead Grays Volume 1 (Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation, 2009), 17.

15 Jon O’Sheal, Pride and Perseverance: The Story of the Negro Leagues, A&E Home Video, 2014.

16 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 422.

17 Harris and Holway, 13.

18 In 1938 and 1939 he played for and managed the Grays in the American Series in Cuba. In the 1939-40 Cuban Winter League season, he played for the Santa Clara team, but Jose Fernandez was the manager. Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 229.

19 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Elander Victor ‘Vic’ Harris” (Carrollton, Texas: Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2011), 25.

20 Lester, 401.

21 Snyder, 167.

22 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 240.

23 Lanctot, 240-41.

24 John Holway, “Negro League Star Harris Dead, Club Won 134 Games in Season,” Washington Post, February 26, 1978.

25 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=harri01vic.

26 Revel and Munoz, ii.

27 Revel and Munoz, ii.

Full Name

Elander Victor Harris

Born

June 10, 1905 at Pensacola, FL (US)

Died

February 23, 1978 at Castaic, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.