Willie Mays

“If somebody came up and hit .450, stole 100 bases, and performed a miracle in the field every day, I’d still look you right in the eye and tell you that Willie was better. He could do the five things you have to do to be a superstar: hit, hit with power, run, throw and field. And he had the other magic ingredient that turns a superstar into a super Superstar. Charisma. He lit up a room when he came in. He was a joy to be around.” — Leo Durocher, Mays’s first major-league manager, in Nice Guys Finish Last1

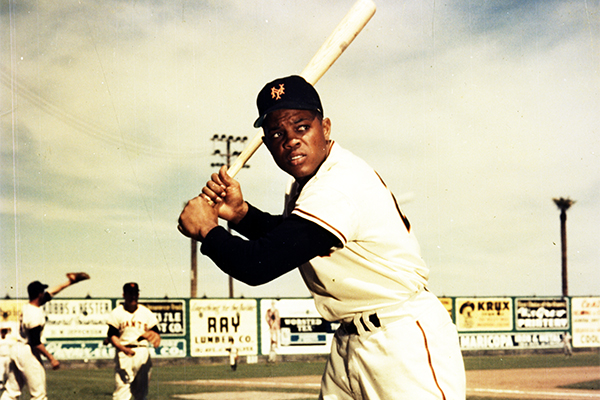

Willie Mays in spring training 1952. (SABR/The Rucker Archive)

Many contemporary players and writers agree with Leo Durocher’s assessment of Willie Mays as the best all-around player in baseball history. Mike Lupica, longtime columnist for the New York Daily News, quoted the late Boston columnist George Frazier on the combination and star power of an athlete like Mays. “That guy has some Willie Mays in him, the same way you used to say this singer or that had some Elvis in him.”2 Former teammate and manager Bill Rigney said about Mays, “All I can say is that he is the greatest player I ever saw, bar none.”3

In baseball’s never-ending attempts to somehow order its gods, Mays is the only contender whose proponents rarely use statistics to make their case. It is as if Mays’ 660 home runs and 3,293 hits somehow sell the man short, that his wonderful playing record is almost beside the point. With Mays it is not merely what he did – but how he did it. He scored more than 2,000 runs, nearly all of them, it would seem, after losing his cap flying around third base. He is credited with more than 7,000 outfield putouts, many exciting, some spectacular, a few breathtaking. How do you measure that? An artist and a genius, for most of his 23 seasons in the big leagues, you simply could not keep your eyes off Willie Mays.

The great ballplayer’s father, William Howard Mays, was named after William Howard Taft, who was the US president when he was born in 1912. The elder Mays worked in the steel mills of Westfield, Alabama, outside Birmingham. Nicknamed “Cat,” he was a semipro baseball player for the Westfield team in the Tennessee Coal and Iron League. Cat’s father, Willie’s grandfather, Walter Mays, was a sharecropper and pitcher. Cat’s wife, Anna (Sattlewhite) Mays, was a high-school athlete who ran track and who led her basketball team to three consecutive state championships.4

Anna gave birth to the third-generation Mays ballplayer, Willie Howard Mays, on May 6, 1931. According to Charles Einstein, the author of several books with and about Mays, a former Birmingham Black Barons teammate once said of Willie Mays, “His momma had but one.”5 In truth, Anna died in 1953 giving birth to her 11th child, but that was long after she and Cat had split up and she was married to a man named Frank McMorris.

It has often been reported that Cat put a baseball in Willie’s crib and that Willie learned to walk at six months, ambling toward a baseball sitting on a chair. Despite these stories, Mays claims that his father did not push him to be a ballplayer.

Willie stayed with his father after his parents separated. When he was 10 years old, the family moved from a company-owned house in Westfield to Fairfield, another suburb of Birmingham. Cat was now a Pullman porter on the Birmingham-to-Detroit train, and Willie was virtually raised by Anna’s two young orphaned sisters, Aunt Sarah and Aunt Ernestine.

In Mays’ several first-person retellings of his childhood, he never stressed childhood difficulties, but of course he had plenty of hardships growing up as an African American in the Deep South during the Depression. He did assert that “there were times that I went to school without any shoes.”6 As was typical for poor families at this time, the Mays household included a friend of Cat’s from the mills, “Uncle” Otis Brooks, as well as several cousins. However, with Cat back working in the mills for $2.60 a day, when there was work, and Ernestine working as a waitress, Mays recalled, “[E]veryone pulled together.”7

Willie attended Fairfield Industrial High School, where he was trained to be a cleaner or presser for a laundry. He starred as a football quarterback and averaged 20 points per game in basketball. The school did not have a baseball team, so he played second base and center field alongside his father on the Fairfield Industrial League team and the semipro Gray Sox. Needless to say, both teams were solely African American, as were their opponents and their fans. These games drew as many as 6,000 fans.

Willie excelled in the Industrial League and, briefly in 1947, for a Negro minor-league team called the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, essentially a farm team for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. When he turned 16, Cat introduced him to Piper Davis, the manager of the Black Barons. Davis became very influential in Mays’ life. That was the year Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers, but Mays asserts that the bigger breakthrough came in 1946, when Robinson broke into White baseball with the Montreal Royals in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ farm system. Mays much later remarked, “Every time I look at my pocketbook, I see Jackie Robinson.”8

Cat Mays, Piper Davis, and Willie’s high-school principal insisted that Mays should graduate from high school, so he played only in the Black Barons’ weekend home games until the school year was over. Ineligible to play high-school sports, he was by far the youngest player on the defending champions of the Negro American League.

Even at 16 years old, Mays played the outfield like a more experienced player. According to Piper Davis, “Nobody ever saw anybody throw a ball from the outfield like him, or get rid of it so fast.”9

In his first professional appearance, batting seventh and playing left field in the nightcap of a doubleheader at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field – shared with the (White) Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association – Mays had two hits off Chet Brewer, whom he called “one of the best pitchers in the league.”10 He moved to center field when the regular, Bobby Robinson, broke his leg. Upon his recovery, Robinson found himself in left field.

According to the Seamheads.com database, Mays batted .239 with 11 RBIs and one stolen base in 21 games with the Black Barons.11 Mays recalled his first meeting with Satchel Paige: “[D]uring the first meeting with the legend, I got a double off Paige my very first time up. I stood on second, dusted myself off, feeling pretty good. Paige walked toward me. ‘That’s it, kid.’ … My next three times up I went whoosh, whoosh, whoosh. …”12

Even at the tender age of 17, Mays came up big in big spots. In the Negro American League playoff series against the Kansas City Monarchs, his two-out, bases-loaded single in the bottom of the 11th broke a 4-4 tie and gave the Black Barons a Game One victory. His double in the bottom of the ninth in Game Two drove in future Giants teammate Artie Wilson with the tying run that sent the contest into extra innings. Another ninth-inning double in Game Three seems to have preceded a game-winning homer by teammate Jimmy Zapp, but the details are sketchy. What is not sketchy is that the Black Barons won three consecutive one-run games before the series moved to Kansas City. Birmingham won in eight games (Game Five had ended in a tie) and moved on to the Negro League World Series.

Mays played in the final Negro League World Series, in 1948, when the Black Barons lost to the Homestead Grays. In Game Three of the Series, he is credited with having made two sparkling defensive plays, chasing down a Bob Thurman fly in the fourth and gunning down Buck Leonard trying to go from first to third in the sixth. A scorching hit through the box in the ninth drove in Bill Greason with the winning run for a 4-3 Birmingham victory, although it is not clear if it was a single or an error by the second baseman. Mays was credited with the RBI. Leonard, a power-hitting first baseman on that Grays squad, had this scouting report on his 17-year-old opponent: “He could run and he could throw. He wasn’t hitting so good, because at that time he couldn’t hit a curveball.”13

According to the Biographical Encyclopedia of Negro League Baseball, Mays batted .311 in 75 games for the Black Barons in 1949, and he continued to tear the cover off the ball in 1950, starting the year batting .330 and slugging .547. With more major-league teams developing an interest in signing young Black players, Mays was obviously attracting attention.

After the 1949 season Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella led a barnstorming team in the South. In a game between the barnstormers and the Black Barons, Mays threw Larry Doby out at the plate after catching a fly ball near the center-field fence. This impressed Campy, and he begged the Dodgers to send scouts down to sign Mays. The scouting report filed by Wid Matthews echoed Buck Leonard: “The kid can’t hit the curveball.”14

In a 1954 letter to Tim Cohane, the sports editor of Look magazine, Giants scout Eddie Montague stated that he was scouting the Black Barons first baseman, Alonzo Perry, for the Giants’ Sioux City Class-A club, when Mays caught his eye. He said, “[T]his was the greatest young player I had ever seen in my life or my scouting career.”15

Leo Durocher wrote in his book Nice Guys Finish Last that Montague reported, “[T]hey got a kid playing center field practically barefooted that’s the best ballplayer I ever looked at. You better send somebody down there with a barrelful of money and grab this kid.”16

Mays concludes in his autobiography, Say Hey: “Montague was in our little house in Fairfield, and I signed my first professional contract. Since I was a minor, my father signed too. … I got a $4,000 signing bonus and a salary of $250 a month.”17

Instead of Sioux City, Mays was sent to Trenton of the Class-B Interstate League. Race played a role in that shift; Sioux City did not want a Black player because there was an uproar over the recent burial of a Native American in a “Whites Only” cemetery there. Even so, Mays was the first African American to play in the Interstate League.18 He thought the level of competition in the Interstate League was far below what he had seen with the Black Barons. “No league that included Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson was a Class B league,” he said.19

Before he could leave Birmingham, Mays gave a friend some money to take his date to the prom. That taken care of, Mays played his first game in June in Hagerstown, Maryland, one of the league cities below the Mason-Dixon Line. His manager at Trenton, Chick Genovese, started him in center field.

In a 1996 interview with a nonprofit organization that recognizes achievers, Mays recalled: “I was the first black in that particular league. And we played in a town called Hagerstown, Maryland. I’ll never forget this day, on a Friday. And they call you all kind of names there, ‘nigger’ this, and ‘nigger’ that. I said to myself … ‘Hey, whatever they call you, they can’t touch you. Don’t talk back.’”20

He also recalled staying at a Blacks-only hotel across town from the team’s hotel, and five of his new White teammates coming to his room to check on him: “About two o’clock in the morning, three players came through the window, and they slept on the floor until about six o’clock in the morning.”21 He identified the players as catcher Herb Boetto, right fielder Eric Rodin, and pitcher Bob Easterbrook.

Mays experienced collapses from fatigue late in the year after several consecutive doubleheaders. He played all-out, running hard on the bases and in the field, and by his own admission “expended more energy than the average player on worrying and thinking.”22 He would collapse in similar fashion several times over the course of his career, but doctors never found a medical cause for it, according to Mays.

After going hitless in his first four games in Hagerstown, Mays wound up with 108 hits in 81 games, batting .353 with 55 RBIs. Clearly, he was ready for a higher level of competition.

In 1951 Mays trained with the Giants’ top minor-league club, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. The major-league team trained in Lakeland, Florida, and their minor-league camp was in nearby Sanford. A game was arranged between the team’s two top farm clubs, Minneapolis and Ottawa, because Leo Durocher wanted to see Mays play, though the Giants’ hierarchy would not bring him to the major-league camp.

In the arranged match, Mays hit a double and a long home run. Durocher began lobbying for Mays to play for the Giants immediately, but owner Horace Stoneham resisted. He said Mays was going into military service “any minute.” Stoneham had his way and Mays began the season with Minneapolis as planned.

The New York Giants won two of their first three games but then lost 11 in a row, while Mays collected 12 hits in his first week with Minneapolis and played a spectacular center field. Durocher’s pleading for Mays intensified. Mays, unaware of this, played still better.

In May Minneapolis was in Sioux City to play an exhibition against the Giants’ farm club there. The Millers had an offday, and Mays went to a movie theater. Between features, the house lights went on and the manager announced, “If Willie Mays is here, would he please immediately report to his manager at the hotel.”23

Manager Tommy Heath informed Mays that he had been called up to the Giants. Mays’ response: “Tell Leo I’m not coming.”24 Heath called, and Durocher laid into Mays on the phone. Mays told him that he didn’t feel that he could hit big-league pitching. Durocher, speechless for perhaps the first time in his life, finally broke his silence and asked Mays what he was hitting. Mays answered, “.477.” (He had a current 16-game hitting streak and a .799 slugging percentage, and was on a pace to score more than 150 runs and drive in 120.) Durocher asked, very quietly but with some scatological punctuation, “Do you think you can hit .250 for me?” Mays responded in the affirmative.25 He was on the next plane to meet the team in Philadelphia. Stoneham bought an ad in the Minneapolis Tribune to assuage the local fans’ outrage at losing their young star.

Manager Tommy Heath informed Mays that he had been called up to the Giants. Mays’ response: “Tell Leo I’m not coming.”24 Heath called, and Durocher laid into Mays on the phone. Mays told him that he didn’t feel that he could hit big-league pitching. Durocher, speechless for perhaps the first time in his life, finally broke his silence and asked Mays what he was hitting. Mays answered, “.477.” (He had a current 16-game hitting streak and a .799 slugging percentage, and was on a pace to score more than 150 runs and drive in 120.) Durocher asked, very quietly but with some scatological punctuation, “Do you think you can hit .250 for me?” Mays responded in the affirmative.25 He was on the next plane to meet the team in Philadelphia. Stoneham bought an ad in the Minneapolis Tribune to assuage the local fans’ outrage at losing their young star.

The Giants were 17-19, in fifth place, on May 25, the day Mays joined the team at Shibe Park. Durocher immediately installed the 20-year-old in center field. The Giants won all three of the games in Philadelphia, though Mays was hitless in his first 12 at-bats. Despite his batting woes, when the team returned to the Polo Grounds, Mays’ first home game saw him batting third against the Boston Braves and their star southpaw Warren Spahn. In his first at-bat, he hit Spahn’s offering atop the left-field roof for a home run, his first major-league hit.

After the homer, Mays went on a 0-for-13 slide, leaving him hitting .038 (1-for-26). At this point, in an often-told story, Mays sat in front of his locker, crying, after taking the collar again. Coaches Freddie Fitzsimmons and Herman Franks sent for Durocher. Mays again said he couldn’t hit big-league pitching. Durocher replied, “As long as I’m the manager of the Giants, you are my center fielder. … You are the best center fielder I’ve ever looked at.”26 Then he told Mays to hitch up his pants more to give himself a more favorable strike zone; he proceeded to go on a 14-for-33 tear.

For a 20-year-old from the Deep South, living in Manhattan could have been overwhelming. The Giants took good care of him, setting him up in the Harlem rooming house of David and Anna Goosby at St. Nicholas Avenue and 155th Street, not far from the Polo Grounds. Mays, still very much a big kid, ate many meals there, and Anna washed his clothes. Neighbors often waited outside for him to arrive home.

Outfielder Monte Irvin, a Negro League veteran, was assigned as the rookie’s roommate and protector. Mays recalled that Irvin looked after him like a big brother. In fact, Mays recalled, “He was a guy that was sort of like my father. … There was a park by his house there, we would go out and just talk, nothing specific, just talk, mostly about life.”27

His stickball-playing reputation was forged in those early days. As New York Daily News columnist David Hinckley wrote, “If you were a 14-year-old New York kid in the summer of 1931, you couldn’t just round up some of your musical pals, knock on Irving Berlin’s window and have Irv come out and write a few songs with you. If you were a 14-year-old aspiring vocalist in the summer of 1941, you couldn’t just grab a couple of tenors, knock on Frank Sinatra’s window and have Frank come join you for a round of harmony. If you were a 14-year-old kid in the summer of 1951, you couldn’t just knock on Willie Mays’ window at 9 o’clock in the morning and have him come out and play an hour of stickball with you. Well, actually, you could.”28 In fact, the games were followed by a trip to the soda shop – Mays’ treat. As Hinckley wrote, this was not some publicity stunt; he actually played. On August 30, 1951, Mays hit two home runs in one game against the Pirates at the Polo Grounds, and then homered in a stickball game later that day.

Mays later recalled encounters with his old stickball teammates while he was working for Bally’s Casino in Atlantic City in the 1980s and ’90s. Someone might say, “Do you remember me? I’m one of the kids that you bought the ice cream for on 155th St. and St. Nicholas (Avenue).” Mays said that, on such occasions, a “smile comes to my face. … That’s a very, very good thing.”29

In addition to his stickball exploits, Mays also babysat for Durocher’s 6-year-old adopted son, Chris. It was not always clear who was babysitting whom. On road trips they would eat together, play catch, go to movies, and read comic books. Police in Cincinnati once stopped them to ask what a White child was doing with a Black man. A call to Durocher cleared up the matter.

On the field, it did not take long for Mays’ game to warrant superlatives. One of the many outstanding defensive plays of his rookie season came at Pittsburgh. Rocky Nelson hit a shot to deepest center field, and Mays tracked it down looking over his shoulder, but the ball hooked away from his glove. He caught the ball barehanded on the dead run. The Pirates’ general manager, Branch Rickey, called it “the finest catch I have ever seen.”30

Others would say that a double play he initiated against the Dodgers with a spectacular catch of Carl Furillo’s slicing line drive and a whirling throw to nab Billy Cox at the plate, preserving a tie, was the best. Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen said, “I’d like to see him do it again.”31

The Giants were playing better, but the Dodgers were running away with the league. On August 11 the Giants were in second place, 13 games behind the Dodgers, 8½ games further behind than when Mays joined the club. This deficit merely set the stage for the Giants’ miraculous 37-7 stretch to catch the Dodgers, and Bobby Thomson’s famous home run to win the best-of-three tiebreaker. Mays was kneeling in the on-deck circle when Thomson hit his homer in the bottom of the ninth in Game Three, and by his own admission, was still frozen there as Thomson rounded second. The 20-year-old was on his way to the World Series.

A few days later, Mays met his idol, Joe DiMaggio, during warm-ups as the Giants readied to face the Yankees, but the Giants were out of miracles and lost in six games. Mays batted .182 in his first World Series.

Mays had made good on his vow to hit .250, winning the NL Rookie of the Year award with 20 home runs, 68 RBIs, and a .274 batting average in 121 games. Durocher wrote, “Just to have him [Mays] on the club, you had 30 percent of the best of it before the ballgame started. In each generation, there are one or two players like that, men who are winning players because of their own ability and their own … magnetism.”32

On his return to the Jim Crow South after the season, the first place he visited was the Woolworth lunch counter where Aunt Ernestine worked. He ordered a glass of water while her back was turned, and when she saw who it was, she chided the Rookie of the Year, “Junior, you know colored can’t sit down at the counter in here.”33

Starting the 1952 season, Mays batted just .236 in 34 games before he was drafted into the US Army, an obligation that would keep him out of the major leagues until 1954. Red Smith chronicled Mays’ last game before his military call-up, in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field: “[T]here was a fine, loud cheer for Willie. This was in Brooklyn, mind you, where ‘Giant’ is the dirtiest word in the language.”34 At the time of his departure, the Giants were in first place, with a 2½-game lead over the Dodgers. The Giants promptly lost eight of ten and were never a factor in the pennant race.

The Army sent Mays to Fort Eustis, Virginia, and assigned him to play baseball for the most part. According to Mays, Durocher kept an eye on him from afar, chiding him when he stole a base with his team leading and sending him money from time to time. The August 13, 1953, edition of Jet magazine reported that Mays broke a bone in his foot sliding into third base in an Army game and would wear a cast for five weeks.35 Mays recalled that he also sprained his ankle in a basketball game, prompting another call from Durocher, telling him to stay off the court.

During his time in the service, his mother, Anna, died, and Mays harbored some bitterness that he wasn’t allowed to resume his playing career to support all his half brothers and -sisters, since his stepfather was unemployed.

Mays estimated that he played 180 games while in the service. When he returned to the Giants in the spring of 1954, he was a half-inch taller and 10 pounds heavier, 5-feet-11 and 180 pounds. When Mays showed up at the Giants’ camp in Phoenix on March 1, the consensus among New York writers seemed to be, “Here comes the pennant,” despite the Dodgers’ 105 wins in 1953. Newsweek predicted in its April 5 issue that Mays could mean the difference between “the second division and the pennant in 1954.”

This optimism is remarkable; how is it possible that one player could make up the 35 games and four places in the standings that the Giants finished behind the Dodgers? His major-league résumé up to that time, in 155 games, included a .266 batting average, a .459 slugging percentage, and 24 home runs – an impressive start to a career, but nothing to make one think he could take a mediocre team past the Dodgers, a group that included Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, and Roy Campanella. On the other hand, Mays had yet to celebrate his 23rd birthday.

Many were not impressed with Mays’ numbers. In an article about Mays written after his retirement, Roger Angell of the New Yorker recalled a spring-training wager with Cleveland columnist Whitey Lewis, who claimed that Mays would not bat .300 for the season. Angell also quoted Indians coach Red Kress saying that “Willie was flat-out overrated.” Lewis sent a check for $20 on September 1 – as Angell described it, “a lovely concession speech.”36

In Mays’ favor was this bottom-line statistic: In the 155 regular-season games for which he had been on the major-league roster (including the ’51 playoff series with the Dodgers), the Giants’ record was 107-48, a .690 winning percentage. Whether or not it was a coincidence, writers and teammates clearly associated Mays with winning.

Bobby Thomson, who played center field before Mays’ arrival in 1951 and again while Mays was in the Army, was now expendable, and the Giants traded him to the Boston Braves for left-handed hurler Johnny Antonelli. Antonelli was just 24 and finished a solid 12-12 for Milwaukee in 1953. The Giants needed another starter, but few would have predicted that Antonelli would lead the league in ERA and win 21 games, one of the key reasons the Giants won 97 games and captured the pennant. The main reason was the center fielder, who became the player Leo Durocher confidently suggested that he would be.

Before the 1954 season, Durocher predicted a .300, 30-home-run season for Mays, and he reached the second of those milestones by midseason, playing the first half of the season on a home-run tear. With Mays batting .326 and ahead of Ruth’s 60-homer pace when he hit his 36th on July 28, Durocher asked him to stop trying for the fences and go for base hits for the good of the team. Mays hit only five more homers the rest of the year, but batted .379 down the stretch.

The Giants were in fifth place in a tight race on May 22, but took over the top spot by June 15, and led by 5½ games at the All-Star break. Although the Dodgers hung tough all season, the Giants clinched the pennant in the final week and won by five games. Willie Mays was back in the World Series, this time as a certified star.

And batting champion. Going into the final day of the season, teammate Don Mueller was hitting a league-leading .3426, the Dodgers’ Duke Snider .3425, and Mays .3422. Mueller finished 2-for-6, Snider 0-for-3 and Mays 3-for-4. After the games, Mays was batting .345, Mueller .342, and Snider .341. In addition to his batting title, Mays hit 41 home runs, drove in 110 runs, and led the league in triples (13) and slugging percentage (.667). To put this statistic into perspective, consider the period from 1931 through 1992, bracketed between two live-ball eras. In those 62 seasons, only two other National Leaguers bested Mays’ slugging percentage: Stan Musial (.702 in 1948) and Henry Aaron (.669 in 1971). Mays also played in his first All-Star Game, and after the season, sportswriters named him the league’s Most Valuable Player, at 23. He is the third youngest National Leaguer to receive the award.

But Mays’ season was not over, and the legend-making was not over either.

On September 29, 1954, the Giants hosted the Indians in the first game of the World Series at the Polo Grounds, New York’s Sal Maglie hooking up with Cleveland’s Bob Lemon. With the score tied, 2-2, in the top of the eighth inning, the Indians put their first two runners on. Although Maglie had allowed just seven hits, Vic Wertz, the next batter, had already tripled and singled twice. Accordingly, Durocher brought in left-hander Don Liddle to face the left-handed-swinging Wertz. Wertz hit a 2-and-1 pitch, a shoulder-high fastball, to deep center field, directly over Mays’ head. No matter. He sprinted directly away from the batter and ran it down in the deepest part of the park, catching it over his shoulder like a receiver taking a long pass from his quarterback. The film clip of this catch is one of baseball’s most famous.37

At least as impressive as the catch was what happened next: As Arnold Hano described it in A Day in the Bleachers: “[He] whirled and threw like some olden statue of a Greek javelin hurler. … What an astonishing throw. … This was the throw of a giant, the throw of a howitzer made human.” Larry Doby had tagged up and made it to third; a man of Doby’s baserunning ability could have conceivably advanced two bases tagging up on a ball hit that deeply in the spacious Polo Grounds. Meanwhile, as Hano described it, the other runner, Al Rosen, “scampered back to first.”38

Liddle, having retired Wertz, was relieved by Marv Grissom after Cleveland manager Al Lopez sent up a right-handed hitter. Later, in the clubhouse, Liddle reportedly said, “Well, I got my man.”39

Many observers believed that play was the defining moment in the Series. The catch clearly saved the first game, as the Giants prevailed, 5-2, in the 10th inning, and may have provided the momentum they needed to sweep heavily favored Cleveland in four games. The October 14, 1954, issue of Jet magazine quotes New York sportswriter Dan Daniel as writing that all great catches “fade out of the book as the Mays classic moves to the top.” Lopez called it “the best I ever saw.”

Mays himself felt that other catches he made were better. For example, he mentions one in Ebbets Field in 1952 on a ball hit by Bobby Morgan. Mays remembered this catch in a 1996 interview:

“I made a catch in Ebbets Field, off of a guy by the name of Bobby Morgan. And it was in the seventh inning, two men on, [two out,] a ball was hit over the shortstop – over the line – over the shortstop. Now you’ve got to visualize this. Over the shortstop. I go and catch the ball in the air. I’m in the air like this, parallel. I catch the ball, I hit the fence. Ebbets Field was so short that if you run anywhere you’re going to hit a fence. So I catch the fence, knock myself out. And the first guy that I saw – there were two guys – when I open my eyes, was Leo and Jackie. And I’m saying to myself, ‘Why is Jackie out here?’ Jackie came to see if I caught the ball, and Leo came to see about me. So I’m saying to myself, ‘This guy is thinking very cool.’ I’m talking about Jackie now. He wasn’t even on the field, he was in the dugout. Now this is my thinking, he may have a different reason. That was my best catch, I think. It was off of Bobby Morgan in Ebbets Field. I caught a lot of balls barehanded, which I felt was good, but that was my best catch, I think.”40

Mays also recalled a catch he made in Trenton in 1950. He said that Lou Heyman of Wilmington hit a ball 405 feet to dead center and he caught it barehanded, bounced off the wall, and threw the ball all the way home on the fly.

All in all, 1954 was a fine season. There were more to come.

Back home in Birmingham, Mays’ Aunt Sarah died in 1954. He continued to send a good portion of his salary, soon to be $25,000, to his 10 half-siblings and to Cat and Aunt Ernestine. Whether it was from grief or the Alabama heat, Mays almost fainted at Sarah’s funeral.

Between the 1954 and 1955 seasons, Mays played in the Puerto Rican League for the Santurce Crabbers, managed by Giants coach Herman Franks. He was in the same outfield as the young and relatively unknown Roberto Clemente, a daunting prospect for opposing pitchers and baserunners. Mays batted a league-leading .393 for the Crabbers, who won the Caribbean Series for Puerto Rico that year. Mays recounted that he played for the team as a favor to Franks and Giants owner Horace Stoneham, whose friend owned the team. However, Mays had grown tired after playing 250 games in 10 months and took six weeks off to rest before the Giants’ spring training in 1955.

The champion Giants fell to a disappointing third place in 1955, despite Mays’ 51 home runs, 127 RBIs, and .319 batting average. He was the seventh player in baseball history to hit more than 50 homers in a season, and Durocher actually had told him to start trying for the fences, contradicting the instructions of the previous year. He also led the NL in triples and slugging average and was second in stolen bases with 24 in 28 attempts, a success rate of better than 85 percent.

Leo Durocher’s personality and outspokenness, tolerated in the pennant- and World Series-winning seasons, grew stale when the team finished in third place. The club announced that he would be replaced by former infielder Bill Rigney for 1956.

Durocher recalled the last game that he and Mays were on the same team. On the final day of the season, during a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies in the Polo Grounds, Durocher called Mays into a small bathroom just off the dugout. Leo told him, “You are the best ballplayer I ever saw. … I’m telling you this because I won’t be back next season.” Mays said, “But you won’t be here to help me.” Durocher said, “Willie Mays don’t need help from anybody,” and then kissed him on the cheek.41

Even at this early stage, Mays’ throwing arm was recognized as the best in the game. The New Yorker wrote on July 10, 1954, that it took Mays three years to learn his famous basket catch, with his hands waist-high and the “gloved hand turned out.” He said his Trenton manager, Genovese, first suggested it, and he perfected it while he was in the Army. Some considered it showboating, but Mays felt that it helped him keep his eye on the ball and position his feet to throw. He led the NL in outfield assists in 1955 with 23, and in double plays with 8.

Mays was widely recognized as the best all-around player in the National League during the 1950s. His defensive prowess and howitzer throwing arm were already established. After he won the batting title in 1954 and hit 51 homers in 1955, the highest total in the National League since Ralph Kiner’s 54 in 1949, he led the league in steals four years in a row beginning in 1956. His 40 steals that year were the most in the majors since 1944. His four-year totals (40, 38, 31, 27) were punctuated by a 78 percent success rate.

On May 6, 1956, his 25th birthday, Mays stole four bases in a 5-4 Giants victory. The next year New York Times writer John Drebinger credited Mays with “returning” the stolen base to baseball and compared his baserunning derring-do to that of Ty Cobb. He wrote, “Perhaps, by reason of Willie’s spark … more players soon may be goaded into trying to bring back what was once one of baseball’s most picturesque plays.”42

The stolen base returned to prominence in no small part because of the emergence of players from the Negro Leagues, which showcased a style more suited to the Deadball Era, with much basestealing and “inside baseball.” Meanwhile, the White major leagues played a more “station to station” style. During the years 1946-1960 the average team stole fewer than 40 bases per season, 75 percent less than in the Deadball Era.

Mays’ impact on the game went beyond his on-field exploits. Baseball historian Jules Tygiel wrote that “Mays, with his indisputable excellence, convinced all but the most stalwart resisters to integration of the need to recruit African-Americans.”43

In his memoir of 50-plus years in the game, Don Zimmer, a contemporary of Mays who began his career as a shortstop for the Brooklyn Dodgers (and also Mays’ teammate on the Santurce team), summed up the prevailing opinion of Mays:

“In the National League in the 1950s, there were two opposing players who stood out over all the others – Stan Musial and Willie Mays. … I’ve always said that Willie Mays was the best player I ever saw. … [H]e could have been an All Star at any position.”44

The 1956 season was marked by Mays’ marriage to the former Margherite Wendell. She had been married twice before, once to a member of the singing group the Ink Spots. In 1958 Mays and Margherite adopted a five-day-old baby whom they named Michael, but the marriage would be troubled.

On the field, Mays was slightly less brilliant in 1956, with “only” 36 home runs, 84 RBIs, and a .296 batting average, for a team that dropped to sixth place. The next season he increased his average to .333, while recording 35 home runs and 97 RBIs. Besides his stolen bases, Mays became the fourth player in the twentieth century to amass 20 or more doubles, triples, and home runs in the same season. He also won the first of 12 consecutive Gold Gloves in that award’s inaugural year.

During the 1957 season, the unemployed Leo Durocher publicly criticized the Giants and Rigney, while still praising his old center fielder. Mays recalled, “After the article came out, I had to apologize for Leo. I admit … that there was a coolness between me and Rigney. We didn’t give each other a chance.”45

In their final home game at the Polo Grounds, on September 29, 1957, the Giants lost to the last-place Pirates, 9-1. Mays had two of the team’s six hits. After the season the Giants left New York for San Francisco while the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, depriving New York of National League ball for the first time since 1882.

The new city did not exactly greet Mays with open arms. After Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was warmly received there, Frank Conniff of the Hearst newspapers commented, “San Francisco is the damnedest city I ever saw in my life. They cheer Khrushchev and boo Mays.”46

Mays recalled that a real-estate broker withdrew his offer on a home because of pressure from other homeowners in the neighborhood. Mayor George Christopher apologized and offered to share his home with Mays and Margherite. In mid-November, they moved into the original house; almost immediately someone threw a brick through a window.

Much has been made of the city’s less-than-warm reception. Charles Einstein suggested three factors: “Mays was the hated embodiment of New York. … He had the temerity to play center field in Seals Stadium, where the native-born DiMaggio had played it in his minor-league days. Also, Mays was Black. The brick that crashed through his window almost as soon as he moved in had to reflect at least one of these viewpoints, if not all three.”47

Relations between Mays and manager Rigney continued to be strained, and Rigney did not help matters when he predicted to the San Francisco media before the 1958 season that Mays would break Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs in a season. He didn’t come close, and that, coupled with the ascendancy of rookie first baseman Orlando Cepeda, likely resulted in Cepeda’s being voted the team’s MVP by the fans. Here are their statistics for 1958:

- Mays: 152 G, 29 HR, 96 RBI, .347 BA, 121 R

- Cepeda: 148 G, 25 HR, 96 RBI, .312 BA, 88 R

Mays’ explanation of Cepeda’s victory in the fan vote: “The fans were disappointed that I hadn’t hit 61 home runs, and Orlando was theirs from scratch.”48

Cepeda’s performance brought him the NL Rookie of the Year Award. However, Mays’ numbers, by some measures, were the best in the league. He led the league in runs scored and stolen bases while winning another Gold Glove; in addition, he almost won the batting title as well. Going into the last game of the season, he was neck-and-neck with the eventual winner, Phillies Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn. Rigney batted Mays leadoff in the final game, hoping to give him more at-bats and a shot at the title. He went 3-for-5, including a double and a home run, but Ashburn finished 3-for-4 and wound up at .350.

Mays’ 1958 was a streaky season; he was batting .400 by early June, followed by a .274 pace through August. A “nervous exhaustion,” which troubled him occasionally throughout his career, was reappearing. He was so tired that during a road trip to Philadelphia he was admitted to a New York hospital and was told there was nothing physically wrong, but that he needed to rest.

In 1959 Mays had his first brushes with serious injury. In spring training, he cut his leg on Red Sox catcher Sammy White’s shin guard, requiring 35 stitches and a two-week recuperation. With the team in first place in early August, Mays broke his right pinkie sliding back to first base after a long single. While he still hit 16 more homers the rest of the way, the Giants as a team tailed off, finishing in third place, four games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers, who went on to win the World Series. Mays hit 34 home runs and batted .313.

Chicago Cub Ernie Banks won back-to-back NL MVP awards in 1958 and 1959. Looking back, he said, “When I was in the Big Leagues, there was a tremendous amount of great ballplayers, but the guy who stood head and shoulders above them all was Willie Mays. He was so exciting – not only exciting to the fans, but to the teams he played with – the Giants – and against. He was just amazing.”49

After struggling their final years in New York, the San Francisco Giants began to introduce a string of players who would form the core of one of the finest squads never to win a championship – the Giants of the 1960s. After Cepeda in 1958, Willie McCovey came up in 1959, winning the Giants their third Rookie of the Year award in nine years. Mays and McCovey would form as potent a left-right power duo as ever played together. They were joined by third baseman Jim Davenport, shortstop Jose Pagan, catcher Tom Haller, and second baseman Chuck Hiller, pitchers Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry, and three outfielder brothers from the Dominican Republic, Felipe, Matty, and Jesus Alou.

The Giants sported a 902-704 record from 1960 to 1969; the most successful team of the ’60s, the Baltimore Orioles, won 911 games. But San Francisco played in only one World Series, losing to the Yankees in 1962 in seven games. By way of comparison, the Los Angeles Dodgers, who finished 24½ games behind the Giants during the decade, won the World Series in 1963 and 1965 behind star pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, and stolen-base king Maury Wills.

The Giants sported a 902-704 record from 1960 to 1969; the most successful team of the ’60s, the Baltimore Orioles, won 911 games. But San Francisco played in only one World Series, losing to the Yankees in 1962 in seven games. By way of comparison, the Los Angeles Dodgers, who finished 24½ games behind the Giants during the decade, won the World Series in 1963 and 1965 behind star pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, and stolen-base king Maury Wills.

The problem with recounting Mays’ career is that the great statistics begin to run together. Although he won two MVP Awards, in 1954 and 1965, he could have won virtually any year in between as well, since he seemed to have the same season every year. He won a Gold Glove 12 times, though they didn’t create the award until Mays’ fifth season. He played in 24 All-Star Games, and these were not just token appearances – he started 18 games in center field, and 11 times played the entire game. By midcareer he was not merely a star player, but was often considered the star, the greatest player ever.

Felipe Alou, who played alongside Mays, played against such luminaries as Frank Robinson and Hank Aaron, and managed Barry Bonds, said, “[Mays] is number one, without a doubt. … [A]nyone who played with him or against him would agree that he is the best.”

The game that may have been Mays’ greatest took place on April 30, 1961, against the Milwaukee Braves at County Stadium in Milwaukee. The night before, Mays and roommate McCovey ate a midnight snack of room-service spare ribs. Mays experienced sharp stomach pains and called for team trainer Doc Bowman. When Mays arrived at the ballpark, he took batting practice but reported feeling very weak. Using teammate Joey Amalfitano’s lighter bat, he homered in his first two at-bats against Lew Burdette. After lining out against Moe Drabowsky in the fifth inning, he hit another round-tripper off lefty Seth Morehead in the sixth. Finally, in the eighth inning, he hit his fourth home run of the day, off Don McMahon. He finished 4-for-5 with 8 RBIs and missed a chance for a fifth homer when the top of the ninth ended with him on deck. After the fourth homer, McCovey quipped, “How ’bout some more ribs?”50

Two months later, on June 29, Mays once again showed his all-around abilities in leading the Giants to a doubleheader sweep at Philadelphia. In the first game, he hit three homers, including the game-winner in the 10th inning of the first game, becoming the fourth player with three or more home runs twice in one season. In the nightcap Mays tripled and doubled, while also gunning down a runner at the plate in one of three double plays in which he would participate in the season. Overall, just another Mays season: 40 home runs, 123 RBIs, .308 batting average, leading the league in runs scored with 129.

On January 31, 1962, Mays signed a contract for $90,000 for the coming season. Once again, 11 years after the “Shot Heard ’Round the World,” the Giants and Dodgers tied for first place and, 3,000 miles west, Mays and Leo would again be involved in a “sudden death” series, this time with Durocher as the third-base coach for Los Angeles.

The pennant race turned on July 17, when the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax, 14-5 and leading the league in strikeouts and ERA, left his start with a circulatory problem in his finger – he would miss two months, and would be largely ineffective when he returned in late September. The Dodgers had a one-game lead when Koufax went down, but valiantly held on.

Mays had his own health woes. In the second inning of a September 12 game in Cincinnati, Mays, feeling hot and dizzy, fainted in the dugout. Revived by Doc Bowman, he was carried away on a stretcher and sent to a hospital. He was diagnosed with tension and exhaustion, and rest was prescribed. Manager and former teammate Alvin Dark insisted that Mays rest until he was ready to return, despite the pennant fight, and he missed three games. In his first game back, Mays hit a three-run home run in Forbes Field off the Pirates’ Elroy Face.

On the last day of the season, the Giants needed to beat the expansion Houston Colt .45s and hope the Dodgers lost to the Cardinals to force a tie. Batting in the eighth inning of a 1-1 tie, Mays hit his 47th home run to secure the 2-1 victory. In Los Angeles, the Dodgers cooperated by losing 1-0 to a Curt Simmons five-hitter.

In the first game of the best-of-three tiebreaker series, Mays finished 3-for-3 with two home runs and a walk, pacing the Giants to an 8-0 victory. His 49 home runs gave him the major-league title for the first time since 1955; the two in the extra tiebreaker games allowed him to pass Harmon Killebrew, who had 48 round-trippers.

The Giants lost the second game, 8-7, leaving 13 runners on base. Durocher, coaching for the Dodgers, reportedly wore the same T-shirt he wore in 1951 on the day of Thomson’s homer. Mays finished 1-for-5, but gunned down Maury Wills at third base in the sixth inning.

In the clincher the Giants trailed 4-2 when the team came to bat in the top of the ninth. The team rallied for four runs on two singles, four walks, and an error. Mays’ line-drive single off pitcher Ed Roebuck’s glove was right in the middle of the inning, southpaw Billy Pierce retired the Dodgers one-two-three in the ninth, with Mays catching the final out.

The Giants and Yankees met in the World Series for the seventh time, but the first since the Giants moved west. The Yankees won in seven games. Mays was left on base carrying the winning run when McCovey lined out to end the Series. Mays batted .250, scoring three runs, driving in one, and stealing one base.

After the World Series, Mays checked into Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco to see if there was a reason for his physical collapses. Three days of tests produced no conclusive diagnosis; however, Mays undeniably had a great deal on his plate at that time. Besides the pennant race, he was in the middle of a divorce from Margherite. She had filed a separate-maintenance suit in 1961 and the couple, deep in debt, nearly filed for bankruptcy. Arnold Hano wrote a story for Sport in August 1963, under the headline “Willie Mays: His Loneliness and Fulfillment.” The Mays he presented was not satisfied with his life and spent most of his evenings alone. He quoted Mays: “I’m lonely. I want to have a family of my own. I have a son and love him, but Michael lives with his mother in New York, and I get to see him only once or twice a year. I want a wife who will love me for myself, because I am Willie Mays, a person, not Willie Mays, a good ballplayer.”51

On the field he was the same old Mays. In 1962 he managed 49 homers and 141 RBIs (the most in his career) and batted .304. He slugged .615 and stole 18 bases in 20 attempts. He just missed out on his second MVP Award, losing one of the Award’s closest ballots, 209-202, to Maury Wills.

Before the 1963 season, Mays got a raise to $105,000 ($5,000 more than Mickey Mantle), making him the highest-paid player in baseball. His health issues did not go away, however, and the strain continued to show. On a trip to Chicago, Mays broke down crying in his hotel room and had the shakes. Doc Bowman gave him sleeping pills and Alvin Dark brought Mays to his room to sleep that night.

Despite his troubles off the field, Mays maintained a high level of play. In the July 2 game against the Braves, he homered in the 16th inning, providing the only run in a 1-0 Giants win. Juan Marichal bested Warren Spahn. Both pitchers went the distance.

In the All-Star Game, Mays went 1-for-3, drove in two runs, scored two, and stole two bases in the 5-3 NL victory. He also made a spectacular running catch in the eighth inning, depriving Joe Pepitone of an extra-base hit. These efforts earned him the game’s MVP Award, established the previous year. Mays also garnered the Award in 1968, becoming the first player to win it twice.

The Giants wound up 11 games out of first in 1963, but no one could blame the center fielder: 157 G, 38 HR, 103 RBIs, .314 BA, 115 R.

Alvin Dark clearly viewed his player with great affection. Mays received a note shortly after Dark was named to manage the Giants in 1961: “Just a note to say that knowing you’ll be playing for me is the greatest privilege and thrill any manager could ever hope to have.”52

The Giants averaged 91.5 wins each year over Dark’s four seasons as manager, and featured one of the most powerful offenses in NL history. However, the 1964 season would prove to be Dark’s downfall and leave a blot on his reputation.

The controversy began in May when a quote from Dark appeared in a book by Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It: “Older people in the South have taken care of the Negroes. They feel they have a responsibility to take care of them. That’s my opinion of how things are.”53

In an attempt to defend himself from media criticism, Dark expressed the view that he would play “nine colored players on the field at one time as long as they can win.” However, he also expressed the view that integration was “being rushed too fast.”54

A few days after the story broke, Dark called Mays into his office and named him the Giants’ first captain since Dark himself had left the team as a player in 1956, and the first African American captain in major-league history. Mays took responsibility for mediating between Dark and many of the Giants’ Latin players, particularly Cepeda. In July the racial and ethnic tensions exploded when Dark was quoted by Stan Isaacs of the newspaper Newsday: “We have trouble [atrocious mistakes] because we have so many Spanish-speaking and Negro players on the team. They are just not able to perform up to the white ballplayer when it comes to mental alertness.”55

Elsewhere in the article, Dark exempted his new captain from this opinion, but every Black and Latin player met in Mays’ hotel room in Pittsburgh to discuss the situation. According to an account in Charles Einstein’s Willie’s Time, Mays, ever the voice of reason, quelled a potential rebellion. He told the players that changing managers during the season had been disastrous in 1960 and it would be disastrous again. Likely working with some inside information from his friends in the Giants brain trust, including vice president Charles Feeney and coach Herman Franks, he also told the players that Dark would not be back the next season, and that, notwithstanding what the manager had said, all of them had gotten a fair shake from him. When Cepeda vowed, “I’m not going to play another game for that son of a bitch,” Mays replied, “Don’t let the rednecks make a hero out of him.”56 For his part, Mays did not speak to Dark for the remaining two months of the season, and beyond.57

In Willie’s Time, Charles Einstein quoted Mays’ real feelings about Dark from that meeting in the Pittsburgh hotel room. Mays said to his teammates:

“I know when [Dark] helped me and I know why. … [H]e likes money. That preacher’s talk that goes with it, he can shove up his ass. I’m telling you he helped me. And he’s helped everybody here. I’m not playing Tom to him when I say that. He helps us because he wants to win, and he wants the money that goes with winning. Ain’t nothing wrong with that.”58

The Giants finished in fourth place, only three games back. Dark was fired on the last day of the season.

Herman Franks, a Durocher crony, was named manager for 1965, and Mays was given much latitude as a field general, almost an assistant manager. When asked why, Franks responded, “Because he knows more about those things than I do. You got any hard questions?”59 The new manager also was a successful investor and helped Mays recover financially, steering him toward solid investments.

On the field, the Giants responded to the firing of Alvin Dark by contending for another pennant in 1965, losing to the Dodgers by just two games. Though Mays turned 34 that season, he hit a career-high 52 home runs, leading the NL in on-base percentage (for the first time) and slugging percentage. Along the way, he won his second MVP Award, 11 years after his first.

One of Mays’ 52 homers was the 500th of his career, on September 13 in the Houston Astrodome, a 450-foot liner to center off Don Nottebart. He was only the fifth player to hit 500 home runs, following Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, and Ted Williams. No National Leaguer had hit 50 in a season since Mays in 1955.

The pennant race was marred by one of the ugliest incidents in baseball history. On August 22 the Giants’ Juan Marichal had knocked down two Dodgers hitters early in the game when he came to bat to lead off the bottom of the third inning against Dodgers ace Sandy Koufax. After Dodgers catcher John Roseboro, in a bit of retaliation, whistled the ball past Marichal’s ear on his return throw to Koufax, Marichal shouted at Roseboro. When the catcher started to get out of his crouch to go after him, the enraged Marichal hit Roseboro over the head with his bat. Naturally, both benches emptied. Mays ran from the dugout to Roseboro’s aid and cradled Roseboro’s head in his hands, with blood staining Mays’ uniform and tears streaming down his face. After play resumed, the next two batters made out, two men walked, and Mays hit a three-run homer, one of his NL-record 17 round-trippers that month.

Roseboro’s account of Mays’ role in the incident is particularly telling. “I guess Mays was more of a ballplayer than he was a Giant,” he wrote in his autobiography, Glory Days With the Dodgers, and Other Days With Others. “He was a sensitive guy, a good buddy, and he didn’t like what his teammate had done to me. … Mays may have been shook, but he hit his fourth homer of the four game series [after the incident]. …”60

Marichal was suspended for eight days and fined $1,750. League President Warren Giles said Mays’ conduct was “fine and decent. … This man was an example of the best in any of us.”61 On later road trips that season, Mays received rousing ovations in Pittsburgh, Chicago, Philadelphia, and, of course, New York. In Los Angeles the Giants were booed lustily, but during his first at-bat, Mays received a tremendous standing ovation, despite the rivalry and the pennant race.

Initially, the Giants went into a tailspin, going 4-8 in the first 12 games after the incident. Then they won 14 games in a row, and by September 16 they were in first place, 4½ games ahead of Los Angeles. But the Dodgers won 13 straight in late September to take the pennant by two games. Marichal, the Giants’ best pitcher, finished the year with a 22-13 record, but likely missed two starts because of his suspension.

Mays’ MVP seasons in 1954 and 1965 form excellent bookends for the story of his career. He was a perennial MVP contender, and many of those 12 seasons are indistinguishable from one another. The 1954 season was his first full year with the Giants, his first and only world championship and batting title, but his first of 13 consecutive seasons of 150 or more games, his first of 12 consecutive seasons of 100 or more runs scored, the first of five consecutive years of 400 or more outfield putouts, and the first of 20 consecutive years making the National League All-Star team. In addition, Mays led the league in slugging for the first of five times in his career. He led the league in on-base percentage for the first time in his career in 1965 (he would lead in that category once more), but the home-run and slugging titles in 1965 would be his last.

The All-Star Game was considered Mays’ greatest stage. He played in 24 midsummer classics, tied for the most of any major leaguer. (Two All-Star Games were played each year from 1959 through 1962 to fatten the players’ pension fund. Both Hank Aaron and Stan Musial also played in 24 All-Star Games.) Mays led the NL to a 17-6-1 record in his All-Star Game career, batting .307 in those contests, with 23 hits in 75 at-bats, 2 doubles, 3 triples, 3 home runs, and 20 runs scored. It is interesting to contrast these numbers with his postseason stats: In 25 career postseason games, he hit one homer, drove in 10 runs, and batted .247.

The All-Star Game was considered Mays’ greatest stage. He played in 24 midsummer classics, tied for the most of any major leaguer. (Two All-Star Games were played each year from 1959 through 1962 to fatten the players’ pension fund. Both Hank Aaron and Stan Musial also played in 24 All-Star Games.) Mays led the NL to a 17-6-1 record in his All-Star Game career, batting .307 in those contests, with 23 hits in 75 at-bats, 2 doubles, 3 triples, 3 home runs, and 20 runs scored. It is interesting to contrast these numbers with his postseason stats: In 25 career postseason games, he hit one homer, drove in 10 runs, and batted .247.

Mays enjoyed his last great season in 1966. He turned 35 that year and played in 152 games, hit 37 homers, drove in 103 runs, and scored 99, levels he would never reach again. He batted .288 (he would never top .300 the rest of his career) and captured his 10th straight Gold Glove, one for every season the award had existed. His 103 RBIs marked his eighth consecutive season with 100 or more, at the time an NL record, although he never led the league in that category. In each of 12 seasons, 1954-1965, he had led the league in at least one major offensive category. For the rest of his career Mays topped the leader board only in walks and on-base percentage in 1971.

Mays continued his assault on the career home-run record, passing Ted Williams (521) in June 1966 and Jimmie Foxx (534) in August. The day after tying Foxx, Mays hit number 535 off the Cardinals’ Ray Washburn, putting him in second place on the all-time list, 179 behind Babe Ruth. Mays recalled, “Until I actually got that ‘close’ at 535, I don’t think I gauged how monumental his record was.”62

The Giants remained in the race until the last day of the season. Along with his other accomplishments, Mays may have helped to prevent a large-scale race riot. Rumors swirled about a potential riot in the predominantly black Hunter’s Point section of San Francisco, and in an attempt to give the people something indoors to do, a game previously not on the TV schedule was added. Mays encouraged fans via radio ads to stay home and watch an important televised game from Atlanta. In Willie’s Time, Charles Einstein wrote, “Mayor John Shelley told Horace Stoneham afterward that nothing else could have prevented all-out rioting and looting. … The TV did it.”63

The aging center fielder battled flu-like symptoms for much of 1967. In July he was hospitalized again for five days after leaving a game with fever and the shakes. He said he never felt strong the rest of the year. In an August contest, the Braves intentionally walked Jim Ray Hart to pitch to Mays. He hit a run-scoring single. At age 36, he finished with a .263 batting average and 22 home runs. Both figures were his lowest in any full season to that point.

In 1968, the “Year of the Pitcher,” the NL won the All-Star Game, 1-0, with its 37-year-old leadoff batter scoring the only run, in the first inning. Mays was starting only because of an injury to Pete Rose. He singled, moved to second on an errant pickoff throw, got to third on a wild pitch, and scored on a double play. It was his last hit in All-Star competition, though he would bat at least once in every midsummer classic until his retirement. As mentioned previously, Mays received his second All-Star Game MVP Award for his efforts, a throwback to the “inside baseball” of his Negro League days.

Mays continued to approach milestones. He ended the 1968 season one steal shy of 300, 13 homers shy of 600, and 188 hits shy of 3,000. His numbers: 148 G, 23 HRs, 79 RBIs, .289 BA, 84 R.

The 1969 season was frustrating for Mays; the Giants finished in second place for the fifth straight year, this time three games behind Atlanta. Manager Clyde King briefly experimented with Mays in the leadoff spot, a position foreign to him, as he had batted third almost exclusively for much of his career. He accepted this move as a team player would, but not before protesting to King that, at age 38, the duties of a leadoff hitter would have him, in his own words, “too tired” before the season was half over. He had other run-ins with King and, coupled with a knee injury, it made for an unhappy year. The Giants’ brass might have agreed with Mays; King was fired after 42 games the next season.

The highlight of Mays’ 1969 season may have come on September 22, when he became the second man to hit 600 career home runs, reaching the milestone and delivering the game-winning RBI in a pinch-hitting appearance against San Diego’s Mike Corkins. He also surpassed 300 stolen bases for his career.

Prior to the 1970 season, The Sporting News named Mays Player of the Decade for the 1960s. He started strong, hitting 19 home runs by the All-Star break. On July 18 Mays singled off Montreal pitcher Mike Wegener for his 3,000th career hit. Play was halted for a ceremony, attended by Monte Irvin, Carl Hubbell, and Stan Musial, the NL career hits leader at the time. All fans were given a free ticket to another game that season, and the Giants presented Mays’ son, Michael, with a four-year college scholarship. Mays finished with 28 home runs and a .291 average, his best numbers since 1966. The team finished 16 games behind, in third place.

In 1971 Mays experienced a renaissance both professionally and personally. Manager Charlie Fox used him as an additional coach to instruct the outfielders. Fox said, “Willie Mays is the greatest player I saw or heard of.”64

Mays hit his 629th career homer on the first pitch he saw on Opening Day. He hit home runs in the first four games of the season, the first time any player had done that. He had a .336 average at the end of May and 14 home runs by the All-Star break, and the Giants were in first place in the NL West for good by the end of April.

On May 6, his 40th birthday, Mays was honored at a banquet attended by such luminaries as Hank Aaron and Joe DiMaggio. Aaron once said that Mays was a greater ballplayer than he, although he saw himself as the stronger hitter. DiMaggio once told a young ballplayer to strive for perfection on the baseball field, and that, while that is impossible, Willie Mays came the closest. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn read a telegram from President Nixon that included a line that Mays was “proof that people over the age of 30 could be trusted.”65

By this time Mays was reaching or eclipsing some milestone once a week. In the opener of a May 30 twin bill, he hit his 638th career homer in a 5-4 defeat of the Expos. The next day, he scored his 1,950th run in a 2-1 victory over the Mets, passing Stan Musial as the all-time leading run scorer in National League history. On June 6 he hit his 22nd career extra-inning homer to lead the Giants to a 4-3 win over Philadelphia, earning the Giants a doubleheader split.

Helping the team any way he could, Mays worked the count more, leading the league in both walks and on-base percentage (.425). He played 84 games in center field and 48 at first base, to rest his legs. After he made several outstanding plays at first base in a game against the New York Mets, their manager, Gil Hodges, said, “I can’t very well tell my players not to hit it to him. Wherever they hit it, he’s there anyway.”66

The Giants outlasted the Dodgers to win the Western Division by one game, but lost to the Pirates in the National League Championship Series. Mays hit his only postseason home run, a two-run blast off Bob Miller, in Game Two.

After the season Mays married Mae Louise Allen in Acapulco, after 10 years of off-and-on dating. He originally got her phone number from Wilt Chamberlain.

The 1972 season began later than scheduled because of a player strike. While reticent in the past on commenting about controversial issues, he said this to the executive board of the union:

“I know it’s hard being away from the game and our paychecks and our normal life. I love this game. It’s been my whole life. But we made a decision … to stick together and until we’re satisfied, we have to stay together. … [If] I have played my last game, it will be painful. But if we don’t hang together, everything we’ve worked for will be lost.”67

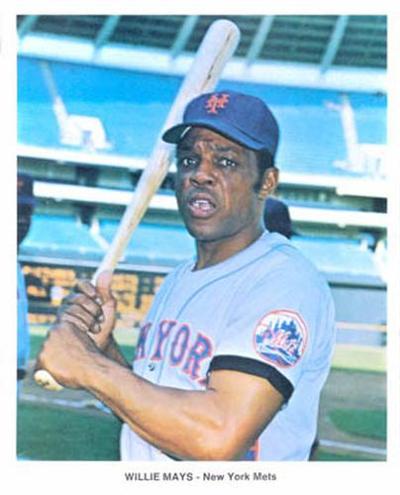

By now, Mays’ salary was $160,000 a year, but he wanted a long-term contract from the Giants that would carry beyond his playing career. None was offered, and rumors began to surface that he would be traded. When the Giants reached Philadelphia in May 1972, New York sportswriter Red Foley informed him he would be traded to the Mets, though it took a few days to formalize the details. Mays would finish his career where he had started. He said, “When you come back to New York, you come back to paradise.”68

He was batting .184 after 19 games when he was traded to the Mets for minor-league pitcher Charlie Williams and $50,000. Horace Stoneham denied that any cash was included in the deal and maintained that he was giving Mays a financial future that the Giants, one of only a handful of family-owned teams left in the majors, could not. Upon joining the Mets, Mays immediately received a contract that would pay him $175,000 per year for the rest of his career and, after he retired, $50,000 a year to coach for the club.

Several days after the trade, the Giants retired Mays’ uniform number 24.

Mays’ first game for the Mets was against the Giants, on May 14, 1972, Mother’s Day, at Shea Stadium. In the fifth inning he homered to break a 4-4 tie, and the Mets won, 5-4. Having the all-time great on the roster did not make manager Yogi Berra’s job any easier. The fans wanted to see Mays, but the manager, of course, had to put the best lineup on the field. As a part-time player, Mays was third on the club in batting average and second in slugging, despite having the worst numbers of his career to this point: 88 G, 8 HRs, 22 RBIs .250 BA, and 35 R. All eight of his round-trippers were with the Mets, and he played 11 of his 69 games as a Met in 1972 at first base.

In preparing for spring training of 1973, Mays had old friend Herman Franks to watch him to see if anything was left in the tank. Franks told him he had one season left. When he had second thoughts about retirement in August, he consulted Franks, who told him to stick by his original decision.

He struggled at the start, hitting .118 in April, and did not drag his average over .200 until July 8. He informed the Mets he would retire at the end of the season, and that the club could announce it in September. He had knee problems that required draining fluid, and favoring one leg caused problems with the other. He also had cracked ribs.

The team wasn’t doing much better, settling in last place all of July and August. They finally escaped the cellar on August 31 but finished 20-8 after that and captured an extremely compressed division.

On September 25 the club had a Willie Mays Night. He resisted the honor initially for fear it would distract the team in the middle of a pennant race. After a one-hour ceremony, many gifts, and an outpouring of affection from the fans at Shea, Mays made his farewell speech:

On September 25 the club had a Willie Mays Night. He resisted the honor initially for fear it would distract the team in the middle of a pennant race. After a one-hour ceremony, many gifts, and an outpouring of affection from the fans at Shea, Mays made his farewell speech:

“I hope that with my farewell tonight, you’ll understand what I’m going through right now. Something that I never feared: that I were ever to quit baseball. But, as you know, there always comes a time for someone to get out. And I look at these kids over there, the way they are playing, and the way they are fighting for themselves, and it tells me one thing: Willie, say goodbye to America. Thank you very much.”69

In the League Championship Series, he made his first appearance on the field as a peacemaker, not a player. In Game Three, Reds left fielder Pete Rose’s takeout slide into Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson ignited a brawl. Shea Stadium fans began heckling Rose in left field, and when a bottle flew from the stands toward him, Reds manager Sparky Anderson pulled his team off the field. The umpires threatened the Mets with a forfeit, so Mays, Berra, and Tom Seaver, among others, walked out to left and pleaded with the fans to let the game go on. The crowd settled down, and the Mets won, 9-2. Mays played only in the fifth and deciding game, but he made the most of the opportunity. He delivered a pinch-hit Baltimore chop single with the bases loaded in the home fifth, and later scored an insurance run in the Mets’ 7-2 victory.

The story of Mays misplaying two balls in center field in the second game of the World Series against the Oakland A’s is always used when the topic is a star athlete who plays too long past his prime. Exhibit B might be Mays’ ultimately harmless stumble on the basepaths in the same game. What is often forgotten is what happened in the 12th inning, when he duped A’s catcher Ray Fosse into calling for a fastball, telling him, “Ray, it’s tough to see the balls with that background. I hope he doesn’t throw me any fastballs.”70 He bounced a Rollie Fingers fastball over the pitcher’s head and into center to drive in the winning run.

Mays’ last career hit in his next-to-last career at-bat provided the game-winning RBI in a World Series game. In the clubhouse watching the game on TV when Mays came to the plate, Mets pitcher and former Giants teammate Ray Sadecki said, “He has to get a hit. This game was invented for Willie Mays a hundred years ago.”71

The Mets lost the Series in seven games. Many of his teammates lauded his impact. Tug McGraw: “I guess I learned as much from Willie Mays as anybody.” Jerry Koosman: “He was still our best player. I begged him not to retire.” Tom Seaver: “Many of the New York writers made him out as a load we had to carry, but, quite the contrary, he helped us carry the load we had all the way down through the season, especially the last month and a half, when we got hot and put it all together.”72

Mays’ post-career years were much less publicly eventful, of course. After retiring as an active player, Mays was a “goodwill” coach for the Mets, working with the young players, visiting farm teams, and appearing at booster-club dinners. He also did public-relations work for the Colgate-Palmolive company for 12 years.

In 1979 the Baseball Writers Association of America elected Mays to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. At his induction ceremony, he was eloquent and humble:

“What can I say? This country is made up of a great many things. You can grow up to be what you want. I chose baseball, and I loved every minute of it. I give you one word –love. It means dedication. You have to sacrifice many things to play baseball. I sacrificed a bad marriage and I sacrificed a good marriage. But I’m here today because baseball is my number one love.”73

That fall he accepted a 10-year deal to do public-relations work for Bally’s Casino in Atlantic City, to greet people and play golf, things he had done at the Dunes Hotel in Las Vegas for years. According to Mays, his agreement prohibited him from gambling within 100 miles of Bally’s. Nevertheless, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn prohibited Mays and Yankees great Mickey Mantle, who had a similar job, from holding salaried positions with major-league clubs. While a number of owners, including the Yankees’ George Steinbrenner and the Pirates’ John Galbreath, had connections with horse racing, and despite the fact that Atlantic City did not (and does not) allow sports wagering, Kuhn forced two of the greatest names in baseball history to sever their ties with the game.

In 1981 New York Daily News writer Bill Madden interviewed Mays to mark his 50th birthday. Although saddened at his banishment, he was tending to his various business affairs, charitable efforts, and the Bally’s job. Madden wrote: “And there was something about Willie Mays gave the fans more satisfaction than probably any other player of his time. Charisma is the way some other people would explain it. Mays has his own explanation as to why he is so beloved. “It’s because I love people,” he said. “You can’t fool people. … I loved what I was doing. …”74

In March 1985, shortly after being named commissioner, Peter Ueberroth reinstated Mantle and Mays, saying, “They are two of the most beloved and admired athletes in the country today, and they belong in baseball.”75

Giants general manager Al Rosen put Mays back in uniform as a spring-training instructor the next year. An All-Star third baseman for Cleveland in the 1950s, Rosen said, “From everything I ever witnessed, Mays was the finest player I ever saw. … His presence is electric. … [P]laying against him, you had the feeling you were playing against someone who was going to be the greatest of all time.” 76

At a ceremony in 1986 honoring McCovey, Mays received a five-minute standing ovation from the Candlestick faithful. In his remarks to the crowd on his special day, McCovey paid homage to his longtime teammate, “Willie Mays, it was an honor to wear the same uniform you wore.”77

The 1990s saw Mays lose three men who were great influences in his life. In 1991 Leo Durocher died, and in 1997 Piper Davis died. Both were father figures to him. Then Mays’ natural father, Cat, died in 1999 at age 88. Willie had set Cat up in an apartment in Harlem in 1954 and moved him out to Oakland in 1958. However, it seemed that the greatest tragedy for Mays was Mae’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease before she even turned 60.

In 2006, Willie Mays remained a part-time consultant for the Giants. A surrogate father to Barry Bonds, his godson, he gave his blessing when Bonds passed him for third place on the all-time home-run list in 2004.

And the accolades kept coming. Washington Post writer Dave Sheinin, in a column about Mays’ 90th birthday, wrote, “There can never be another like Mays, if only because the elements for his creation no longer exist. Baseball no longer holds the imagination of the country the way it did in the 1950s and ’60s. …”78 Despite their political differences, Presidents Bill Clinton, George Bush, and Barack Obama, baby boomers all, idolized him and desired contact with him. Clinton, a frequent golf partner of the Say Hey Kid, said, “When you see [Willie Mays] do something you admire, the image of that makes a mockery of all forms of bigotry.”79 Bush, who named Mays the commissioner of the White House T-ball league, said, “When I was growing up, I wanted to be the Willie Mays of my generation.”80 When President Obama was elected as the first African American in the job, Mays sent him a note: “Dear Mr. President, Move on in. Your Friend, Willie Mays.” Mays subsequently joined the president on Air Force One traveling to the 2009 All-Star Game.

When Peter Magowan, a Giants fan from the Polo Grounds days, purchased the team in 1993, one of his first acts was to give Mays a lifetime contract to be a part of the Giants organization. On the occasion of Mays’ 80th birthday in 2011, Daniel Brown of the San Jose Mercury News wrote, “Magowan was surprised a few years ago when Mays approached him about a contract extension. ‘Willie, it’s a lifetime contract. You know what that means, right?’ Magowan said. ‘I know what it means. I still want an extension,’ Mays replied.”81

Mays had requested the extra year to ensure that Mae would be cared for once he was gone. On April 19, 2013, Mae died of complications from her Alzheimer’s disease.82

In 2015 President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom,83 and on August 27, 2022, the New York Mets retired Mays’ uniform number 24. While not present at the Mets Old Timers Day ceremony in which the number retirement served as a surprise, Mays sent a statement that was read by the master of ceremonies, Mets announcer Howie Rose, which said in part, “you might lose a lot of details after so many years, but what I can never forget is the way it felt to be back in New York City playing for the fans. Mets fans always gave me the biggest ovations and the loudest “thank yous” ever. Today I return those thank yous from the bottom of my heart. Thank you, Mets!”84

When The Sporting News polled fans to name the All-Century team for the twentieth century, Mays placed second to Babe Ruth. He wrote the foreword for the book honoring the team: “It’s a great honor to be named the No. 2 player in baseball history. … I have the satisfaction of knowing that when they call my name, everybody knows me. If you’d asked me when I was 15 in Birmingham if all this could happen, there’s no way I would have said yes.”85

Mays died at the age of 93 on June 18, 2024, just a few days before the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals played a game in his home state of Alabama at Rickwood Field.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Honig, Donald. The All Star Game (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Company, 1987).

Klima, John. Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2009).

Museum of Living History, Academy of Achievement Interview with Willie Mays, February 19, 1996 (achievement.org).

The Sporting News Selects Baseball’s Greatest Players: A Celebration of the 20th Century’s Best (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Company, 1998.)