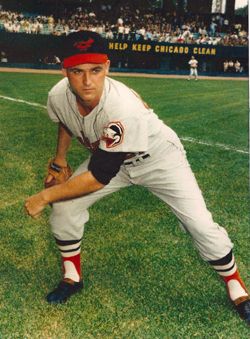

Art Quirk

Stories about Art Quirk’s golden arm and Ivy League degree accompanied the left-handed pitcher on his rise to the major leagues. There were double-digit strikeout games and a no-hitter. Most newspaper profiles mentioned the rarified source of his college diploma.

Stories about Art Quirk’s golden arm and Ivy League degree accompanied the left-handed pitcher on his rise to the major leagues. There were double-digit strikeout games and a no-hitter. Most newspaper profiles mentioned the rarified source of his college diploma.

But the excitement of his 1962 debut was short-lived when he was bumped from the big-league roster by a future Hall of Famer. Quirk returned to the majors in 1963 but was sent down again by an expansion team running quick auditions for its pitching staff. A sore arm forced him to retire, and Quirk began building a lifelong legacy supporting children and adults with developmental disabilities.

Arthur Lincoln Quirk, Jr. was born April 11, 1937.1 He was the first child of Arthur Lincoln Quirk and Lucy (Fogarty). The Quirks were of Irish, Welsh, and English descent.2 They lived in Narragansett, Rhode Island, a seaside town of less than 2,000. Quirk’s younger siblings were William (born 1940), Mary (1943) and Judith (1946). By the time Mary arrived, Art was already pursuing his life’s goal. “I have wanted to pitch in the major leagues, in fact, since I was 6 years old,” he said in a 1962 profile in The Sports Illustrated.3

The Quirks’ connection to baseball dated to Art’s grandfather, who was an industrial league pitcher in the early 1900s. His father, Art Sr., pitched for Providence College in the early 1930s and was a batterymate of catcher Birdie Tebbetts. The elder Quirk turned down a contract from the Boston Red Sox to stay in college.4 In 1938, when he was on the faculty of Providence College, he was appointed coach of the Friars.5

As a child, Art “used to go out with a ball and just hit it against the garage door. He spent hours doing that, throwing and catching and throwing and catching,” said his widow Kit, relaying the memories of her parents-in-law.

In the fifth grade Quirk could pitch to the corners of the plate consistently; in seventh grade he had a “roundhouse” curve. He played stickball with his younger brother Bill. Art graduated from South Kingstown High School in 1955, where he played football, basketball, and baseball. It was on the diamond that he shined the brightest.

South Kingstown won state championships in 1953 and 1955 when the Rhode Island baseball tournament was for schools of all sizes. From 1953 to 1955 the team went 36-6.6 Lefty Quirk threw a no-hitter and once struck out 20 in a game.7 Quirk credited his catcher, Aaron “Sacky” Briggs, with elevating his game. “He was so steadfast and confident that he inspired me to do my best,” said Quirk. “We had wireless communications before it was invented.” Briggs was signed by the Chicago Cubs in 1957 and played two seasons in the minors.

Quirk was named to the Providence Journal All-State team as a sophomore pitcher in 1953. The next two years, 1954 and 1955, he was named to the team at two positions, pitcher and outfielder.8 When Quirk was playing first base or outfield, his coach would often bring him in to pitch. “He’d come in and get the team out of trouble,” said his brother Bill. “He did it as much as four times in one game.”

Quirk was ranked third in his class academically and was offered a four-year academic scholarship to Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire.9 Quirk preferred nearby Brown University in Providence. His mother had attended its women’s affiliate, Pembroke College, and his girlfriend Kathleen (Kit) Harkins would be much closer.

Major-league teams were also tempting Quirk. The family shared meals with scouts Jeff Jones (Braves), Len Merullo (Cubs), and Joe Cusick (Orioles). The Cubs offered him a $30,000 bonus to sign, but Quirk’s college graduate parents strongly discouraged that option. “It was really not up for a vote,” said Kit. The scholarship persuaded Quirk to attend Dartmouth.10

At Dartmouth, initially limited to freshman-only teams, Quirk played soccer and baseball. The losing baseball program got a jolt in 1957 from its new coach, former big-league first baseman Tony Lupien, and sophomore Quirk. The Big Green had its first winning season since 1949. On May 18 Quirk struck out 17, tying the school record, in a three-hit victory over Army.11 He finished 2-1 with a 4.29 ERA, striking out 32 in 21 innings, as he was limited to three appearances due to a sore arm.12 He had three hits in nine at-bats.

Quirk was Dartmouth’s ace in 1958. With his father watching on April 19 at Fitton Field in Worcester, the 5-foot-11, 170-pounder struck out 10 in a win over national powerhouse Holy Cross.13 It was his fifth straight victory (including an exhibition game) and brought his strikeout total to 53 in 40 innings. The moment brought tears to the eyes of his dad.14 Twenty-eight years earlier he had pitched Providence to a win over Holy Cross, beating a Crusaders team led by the same coach, Jack Barry.15

Dartmouth went 11-4 to qualify for its first-ever NCAA playoffs. Quirk brought his 7-2 record and sub-2.00 ERA against Connecticut in the opener of the double elimination playoff. The game was scoreless through seven innings.

After a leadoff UConn triple in the top of the eighth, Quirk struck out two and had two strikes on the next batter. He threw a sharp breaking pitch which drew swinging strike three, but the ball got past catcher Woody Woodworth. The runner on third scored the only run of the game on what was scored a wild pitch. In ensuing years, when Quirk and Woodworth would sarcastically recall that pivotal, game-changing moment, Woodworth would say, “Wild pitch.” Quirk would respond, “Passed ball.”16

Dartmouth lost the second game and was eliminated, but Quirk’s breakthrough season continued. He was named MVP of the Eastern Intercollegiate League.17 Then came another $30,000 contract offer from the Chicago Cubs.18 “He agonized over it for a while,” said his son Kent, “and decided that it was much more important to finish college and get his degree.”

Next was the summer Cape Cod Baseball League; Quirk joined Orleans. In preparation, Quirk and his brother Bill, a rising sophomore at Dartmouth, played stickball with a hard plastic ball the size of a golf ball.19 And there was wiffle ball with Dartmouth baseball teammate (and roommate) Dave Gavitt, whose later basketball accomplishments led to induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Those backyard drills turned the two-year .214 part-time college hitter into the Cape League’s batting champion with a .475 average.20 “The ball was like a grapefruit. I couldn’t miss. Everything was a line drive.” On the mound he was 9-0 with a 1.12 ERA. “It’s doubtful that any player ever had a more dominant season on Cape Cod than Quirk in that magical 1958 campaign,” the league proclaimed.21

Dartmouth slipped to 10-14 in 1959, but Quirk went 8-5 with a 2.08 ERA in 104 innings. He struck out more than one per inning for the third straight year. As a junior and senior, he pitched more than 50 percent of Dartmouth’s innings. “I used to say they pitched him and prayed for rain,” said Kit.

Over 60 years later that overpowering workload placed Quirk in the top ten in four career pitching categories: wins, ERA, strikeouts, and complete games.22 They also took a toll. “I didn’t have any shoulder pain until Dartmouth,” said Quirk.

With several teams courting Quirk, Red Rolfe, – Dartmouth Athletic Director and former New York Yankee third baseman – said, “I’d like to see him have a little more speed starting out. But Art can get his curve over the plate, has a change of pace, and has added a sidearm pitch for lefthanders.” 23

Quirk signed with the underperforming Orioles, theorizing that would help his rise to the majors. He received a $15,000 bonus and was assigned to Amarillo (Double-A, Texas League). He set a five-year deadline. “If I didn’t make it financially or to a certain level of success I was going to quit.”

Innings-eater Quirk arrived in Texas in late June when the Gold Sox pitching staff had been depleted after a succession of doubleheaders.24 25 Without relief available, he lost a complete game, 12-11, despite “throwing the best stuff I knew how.” He realized “it wasn’t going to be easy for me to hop up to the majors.”

In relief Quirk compiled a streak of 19 scoreless innings.26 Eight of the innings came on July 26. He entered the game in the second with the bases loaded and nobody out. He struck out the side, then nine more in the remainder of his outing, allowing only four baserunners.27 That earned him a start in August, a victory that raised his record to 4-1.28

On August 20 he pitched six effective innings in the first game of a doubleheader. In the second game he relieved in both the ninth and 10th innings, with a stint in center field between.29 Quirk finished 5-4 with a 3.86 ERA in Amarillo.

After the season he married Kit Harkins and planned to start a master’s degree program at the University of Rhode Island. Instead, he pitched for Clearwater in the Florida Winter League. “If anybody in school [college] had ever suggested I’d spend my honeymoon watching baseball games, I’d have laughed out loud,” said Kit. She later prepared a Thanksgiving dinner for fellow Oriole players. Quirk’s 4-1 record earned an invitation to the Orioles major-league spring training in 1960.30

Quirk pitched just one inning in that camp, even though he was not cut until April 9.31 He was assigned to Little Rock (Double-A, Southern Association). He started 18 games (32 overall) and went 7-9 with a 3.56 ERA, 25 percent below the league average.

“The last two months I thought I could beat anyone,” said Quirk. “I was averaging ten, 11, 12 strikeouts a game.”32 He noted an earlier 26-inning scoreless streak that included two 1-0 shutouts. The Travelers’ youngest pitcher was in the top five in the Southern Association in hits and strikeouts per nine innings. He pitched a three-hit shutout in the playoffs as his team won the Southern Association championship.

In 1961 Quirk was again invited to the Orioles big-league spring training, this time vying for a lefty pitcher roster spot.33 Third baseman Brooks Robinson, an Oriole since 1955, said he was a “crafty little lefthander.” Quirk hung on until the final cut and was sent down to Rochester (Triple-A, International League), where he became a fixture in the starting rotation.34

In his first start he threw a one-hitter. At the end of June, he was 5-3 with a 2.76 ERA, with more than a strikeout an inning,35 a pace he maintained through the season. On July 4 he threw a (seven-inning) no-hitter.

Kit and one-year old son Kent sometimes followed Art on the road. With the rear section of their station wagon equipped with cloth bumpers to create a playpen, mother and son traveled to nearby International League cities. Finding gas and food was not a worry, said Kit. “I always went into places where truck drivers stopped because they were kind and sweet to me,” she said. “They loved that there was a little guy there and they were very protective and kind.”

Quirk finished the season 10-8 with a 3.58 ERA. In just 24 starts he was among the IL leaders in strikeouts, complete games, and shutouts. The lefty’s stature and delivery drew comparisons to Whitey Ford, who was an inch shorter and a few pounds heavier.36

As Quirk pushed towards the majors, his family’s academic background and exotic degree in Far Eastern and Russian History were companion topics to his pitching. One profile of the “Brainy Bird” noted his graduation with honors from Dartmouth and that his college pitcher/coach father was the chair of the University of Rhode Island physics department.37 Another described Quirk as “intelligent” and noted that his father chaired the Rhode Island Atomic Energy Commission, a high-profile appointment in the early years of the Atomic Era.38 Clyde King, Quirk’s manager in Rochester for two years, reported, “He’s a quiet sort. That’s a sign of intelligence.”39

In 1962 Baltimore needed to replace hard-throwing Steve Barber’s 18 wins, as the lefty had to fulfill a military commitment. The Orioles were optimistic that Quirk was a good option, notwithstanding some concern about “arm trouble.”40 The front office was prepared to meet Quirk’s preparation requirements. “He says he needs five days between starts,” said President Lee MacPhail, “but that’s not a serious drawback.”41 Quirk disagreed and was so insistent that he wrote a letter to the front office saying he could start on three days rest.42

Although Quirk was at his third major-league spring training, he faced top-level hitters for just the second time. His opponent was the World Series champion New York Yankees, a juggernaut that had won 109 games the prior year. In the dugout before the game, Quirk said he was so anxious, “I almost considered putting my street clothes back on and going home.”

Quirk started the fourth inning. “I figured I’d be facing the tail end of the Yankee lineup. I must say I was a little surprised to see Mickey Mantle moving into the batter’s box,” he said of the 1962 MVP runner-up. He missed with two fastballs and fell behind 2-0.

Catcher Gus Triandos, a three-time All-Star with a strong arm and an erratic glove, signaled for a curve. Quirk got a called strike, then shook off Triandos’ signal for a fastball so he could throw a change-up. Mantle was out in front and “missed it by six feet. He wasn’t expecting that from a rookie. He forgot I was from the Ivy League,” joked Quirk. Mantle popped up a curve behind the plate, but the foul bounced off Triandos’ glove for an error. He threw another curve that Mantle skied to left. Boog Powell, a left fielder transitioning to first base, stood under it. “Powell was there pounding his mitt ten feet from the wall,” said Quirk. The ball went over the left fielder’s head, hit the base of the concrete wall, and caromed back through his legs. The shortstop fielded it and Mantle slid into third with a triple. “So here was Mantle on third,” Quirk lamented, “after I figured I had gotten him out twice.”

Quirk pitched 20 Florida innings with a 3.99 ERA, won two games, and earned a roster spot. He was named the Orioles’ “Best Young Pitcher” by The Sporting News in a thumbnail AL preview.43 Quirk headed north with the 28-player squad, realizing that the roster would be cut to 25 a few weeks later. Manager Billy Hitchcock said, “Art has looked real good at times, and I give him a chance to stick after the cutoff.”

After a forgettable debut on April 17 against the Yankees – a walk to Mantle then two singles – Quirk started on the road against the first-year Senators on the afternoon of April 21. He pitched into the sixth inning, allowing nine baserunners (five hits, four walks) but none scored. With a 1-0 lead and one out and a runner on first, Wes Stock relieved Quirk. Stock induced a double play, held an eventual 3-0 lead, and saved the rookie’s first win.

Quirk left the game because of a blister on a pitching finger. He attributed it to the new grip needed for a fourth pitch he developed the prior week, a slider, “because my curveball was letting me down.”44 The right-handed hitter also notched his first hit, a single off Claude Osteen.

The lefty lost two of his next three starts. He allowed 16 baserunners in six-plus innings in the two losses. But in between, a six-strikeout, three-run effort in six innings against the Angels kept him on the reduced 25-player roster. Quirk’s major-league status remained tenuous, however, because Barber was able to meet his military commitment during the week and pitch for the Orioles on weekends.

On May 17, the Ivy League lefty was in a marquee matchup with headline-grabbing Angels rookie Bo Belinsky. The Hollywood sensation Belinsky was 5-0 and 12 days removed from a no-hitter. Quirk gave up a run in the second, but the Orioles scored six runs in three innings to chase Belinsky. Baltimore won, 6-4, with Quirk striking out eight in 7 1/3 innings. He scattered ten hits. Belinsky joked after the game, “It took a guy with a college education to beat me.”45

Three days later Quirk gave up two runs in two innings, pushing his ERA to 5.93. That made him expendable when the Orioles signed 234-game winner and future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts as a free agent. Manager Hitchcock said Quirk remained the team’s top pitching prospect. “Quirk needs more experience,” he said, noting that the lefty had less than three full seasons in the minors.46

At Rochester Quirk appeared in 29 games, starting 20, and finished 7-6 with a 4.71 ERA. Fellow Red Wings pitcher (and 2011 Hall of Fame inductee) Pat Gillick described Quirk as “an excellent competitor with a real feel for pitching.” Without an overpowering fastball, Quirk used “a three-pitch repertoire and was not afraid to use his curve or change when behind in the count.” Gillick also recalled Quirk’s “northeastern dialect” and “dry sense of humor.”47

Quirk’s 1962 debut made him the second Dartmouth pitcher in the majors.48 He joined 1952 graduate left-hander Pete Burnside, who appeared in 40 games for Washington.49

In the off-season, Quirk worked as a technical editor at the Naval Underwater Ordnance Station in Newport, Rhode Island. As the Caribbean winter season approached, the Orioles asked Quirk to play in Puerto Rico. He was reluctant. “I have a family to support,” he said. His $500 per month Navy salary was far more than he would earn playing winter ball. The Orioles called every other day; each time a higher authority pressed him. After hearing “about four ‘no’s’ from me,” said Quirk, the calls stopped.

On December 5 Quirk was driving home from work. On the radio he heard he had been traded to the expansion Washington Senators. “I guess they got me. They sent me to a last place team,” he said. He was traded for fellow Dartmouth grad Burnside as part of a five-player trade.50 Quirk became a starter candidate for the second-year expansion Senators, according to manager Mickey Vernon.51

Quirk started three times in the first seven weeks and won one game, but he was inconsistent overall. On April 19, his best outing, he held the Yankees to three runs and three hits in seven innings, but he left with the game tied.

Another bright moment occurred on May 12 at Fenway Park when Quirk was honored by the Massachusetts Town of Orleans at the Red Sox annual Cape Cod Day. In recognition of his All-Star summer with the town’s Cape Cod League team five years earlier, he was presented with an engraved Hamilton wristwatch by US Congressman Joseph W. Martin Jr. “It’s one of my prized possessions,” Quirk said.52

He earned a victory on May 18 against the Tigers despite leaving the game for a pinch-hitter with Washington trailing 3-1 after five innings. When the Senators scored four runs and held the lead, Quirk got the win. After a relief appearance on May 22, Quirk had an ERA of 4.29 and had allowed 31 baserunners in 21 innings.

The next day he was sent down to Double-A York, replaced on the roster by fellow Dartmouth lefty Burnside, who had been released by the Orioles. The frustrated Quirk threatened to retire, but ultimately reported to York after a few days.53

Quirk pitched two games for the White Roses, going 1-1. He won a two-hitter, then lost his second game, leaving with an arm injury after seven innings.54 He was then promoted to Toronto, the Braves/Senators’ Triple-A co-op team. He went 1-4 with a 4.29 ERA in 19 games. His third stint in Triple-A lacked his prior luster – strikeouts per inning were down and walks per inning were up. One of Quirk’s hallmarks, the complete game, was absent. He had none in seven starts. He had battled a sore arm for most of year.55 Art kept quiet about it, said Kit. “He was reluctant to complain about it too much because that meant he’d be gone [demoted] again.”

As scheduled, Quirk conducted his five-year check-in. “I could make more outside of baseball than I could inside of baseball,” he concluded. Quirk sat out the 1964 season, but in early 1965 – just a few weeks after his daughter Kerri was born – he announced a comeback bid. “He bowled me over with that one,” said Kit. Quirk went to early spring training with the Senators, but tendinitis ended the effort in mid-February.56 His career record in 48 1/3 innings was 3-2, with a 5.21 ERA.

In retrospect, Quirk wondered if he should have accepted one of the Cubs’ bonus offers. When he signed with the Orioles in 1959, he thought the rebuilding franchise would offer a quick route to the majors. The team had finished higher than fifth once since 1945.

But Baltimore was furiously signing players, over 700 between 1954-58.57 The Orioles went from no Triple-A teams (1953-55) to one (1956-57) to two (1958-60). In 1961, pitchers 23-years-old and under pitched 57 percent of Baltimore’s innings, limiting opportunity for Quirk. “Had I taken that $30,000 offer [from the Cubs], I might have had a very different baseball career,” he told Kent years later.

In 1966, when Kent was five and Kerri was an infant, the Quirks moved to Enfield, Connecticut, a town located in the northern part of the state, 30 miles north of Hartford. The family was also reeling from the recent national rubella epidemic. Pregnant Kit was among the 12 million people in the United States who became infected. Kerri was born deaf, and later diagnosed with autism and aphasia. In 1969 their third child, Christopher, was born.58

While providing support for Kerri was demanding, the Quirks wanted their family to live together. “This was at a time when kids like Kerri were often institutionalized,” said Kent. “And my parents couldn’t imagine doing something like that.” So, Kit learned sign language to communicate with Kerri.

One of the Quirks’ first community projects was ensuring Kerri’s safety in their neighborhood. “My Dad convinced the town to install signs on our street that said, ‘Caution. Handicapped Deaf Child,’” said Kent.

As Quirk’s career progressed from supervising telephone operators for AT&T to selling computers for IBM and Xerox, the family moved south to Glastonbury, a town bordering Hartford. He continued to sell and market computer technology. The most prominent was TravTech, a subsidiary of Travelers Insurance, where he was President and Chief Executive Officer.

The Quirks’ backyard was the neighborhood sports venue. “The baseball diamond was in the corner,” said Kent. The football field would run one way and the soccer field would run the other depending on what we were playing.”

In Glastonbury, the Quirks leveraged the 1975 federal law that required public schools to provide education to all children, including those with disabilities. First there was a showdown when Kit insisted to the Director of Special Education that school-age Kerri qualified for public school services. On a school day Kit and Kerri met the director in her school office.

“I’m leaving her,” Kit advised.

“What do you mean?” the director responded.

“It’s a school day and I’ll be back at 3 o’clock,” Kit informed the director.

Kit walked out, leaving Kerri behind. The director hurriedly followed Kit, realizing the intensity of the family’s commitment to Kerri. “I think they realized they had to do something,” said Kit.

Ultimately more than persuasion was needed to ensure Kerri received school services. “When I was in high school my parents were going to court to get Kerri covered,” said Kent.

Kit also began working at the American School for the Deaf in West Hartford, where Kerri attended a day program.59 Kit took night classes to earn a college degree in special education, then a master’s degree. She became a teacher at the American School for the Deaf and eventually Supervisor of Special Education.

In the summer Kerri attended Camp Crossroads, a traditional summer camp for children with disabilities – something that was hard to find. One of the founders, Chris MacNaboe, wanted to expand services and develop a non-profit agency. The timing was perfect, because Art was acutely aware of the need for more services for children with disabilities. MacNaboe enlisted Art and Horizons was born in 1979.

For the next 35 years Quirk was the guiding force behind the evolution of Horizons into a broader service provider. “The legacy he left for those with disabilities is quite outstanding,” said founder and Chief Executive Officer MacNaboe. Quirk was Board chair for 18 years.

As Horizons grew from a summer camp to a full-year service provider for people with disabilities, Quirk provided leadership in fundraising, marketing, staff training, finance, communications, and technology. He also coached the Horizons staff softball team. “He was very passionate about making sure we were person-centered with our services and that we were doing what kids enjoyed,” said MacNaboe. New initiatives included day programs for public school students, supported living, group homes, supported employment and retiree transition.

Kerri Quirk has lived at Horizons for many years. She operates the “Kerri Art Studio and Gallery” in Willimantic, Connecticut. The Quirks retired in Stonington, CT (on the Rhode Island border) to stay close to family and friends in both states.

Recognition of Quirk’s baseball achievements continued well after his career. In 1984 he was inducted into Dartmouth’s Wearers of the Green with his coach Tony Lupien. They were inaugural inductees into Dartmouth’s honor roll of athletic excellence. In 2002 Quirk was inducted into the International Scholar Athlete Hall of Fame for “distinguished athletic, academic and humanitarian achievements.”60 The ceremony was held by the Institute for International Sports on the University of Rhode Island campus, where his father was a professor for many years. In 2009 Quirk was elected to the Cape Cod Baseball League Hall of Fame.61

Quirk earned another distinction despite pitching in just 14 major-league games. He is one of two undefeated pitchers in the 11-year history of the expansion Washington Senators. His April 1963 win gave him a 1-0 career record. Later that year Ron Moeller went 2-0. No other pitchers were undefeated for the new Senators before they moved to Texas in 1972.62

When Art passed away in 2014, Horizons recognized him as its “founding father” and for dedicating “his life to making a difference in the lives of people with special needs.”63 “Right until his last days he was involved with us,” said MacNaboe.

While Quirk was resting at home in his final month, his Dartmouth catcher Woodworth visited to reminisce. As Woodworth was preparing to leave for the last time, he recalled the game-deciding pitch in the 1958 NCAA playoff game. Going to the door, the catcher said loud and clear: “Passed ball.”64

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Art’s widow Kit and son Kent for sharing their memories of Art in separate interviews listed below. In addition to their interviews, the Quirks shared six audio recordings of family conversations with Art from November 2014.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Gary Rosenthal.

Sources

This biography draws extensively on the interviews with Kit and Kent Quirk listed below, the six family audio tapes noted above, and The Sports Illustrated profile of Art published April 16, 1962, https://vault.si.com/vault/1962/04/16/the-springtime-trials-of-a-rookie.

Other sources include: Baseball-Reference.com; Retrosheet.org; Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Art Quirk; US Census Bureau, 1930 US Census, and 1910 Census; Dartmouth College Department of Athletics, baseball statistics of Art and Bill Quirk, and box score of the June 5, 1958 NCAA playoff game.

Personal Interviews

Brooks Robinson, telephone interview, October 25, 2021

Pat Gillick, email, October 27, 2021

Christine MacNaboe, telephone interview, November 1, 2021

Kent Quirk, telephone interview, November 6, 2021

Kathleen Quirk, telephone interview, December 9, 2021

Notes

1 Quirk’s baseball records state that he was born in 1938. Quirk’s son Kent said that when his father’s baseball talent became evident, an unknown person, possibly a baseball scout, suggested that the family report Art’s birth year as 1938 instead of 1937. The 1940 Census, effective as of April 1, 1940, reports Art as being two years old on his last birthday, which would have been April 11, 1939. Also, Quirk’s gravestone shows a birth year of 1937, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/139275712/arthur-lincoln-quirk. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

2 Arthur Quirk’s parents were from Ireland and Wales, and Mary Quirk’s parents were from Ireland, according to the 1910 US Census. The Census lists Arthur Quirk’s mother as born in England, but Kent Quirk has visited his great-grandmother’s home and it is located in Wales. Apparently, the census taker considered the country of Wales to be part of England.

3 Huston Horn, “The Springtime Trials of a Rookie,” The Sports Illustrated, April 16, 1962: 40. This biography draws extensively on this published interview, telephone interviews with Kit and Kent Quirk and six family audio tapes recorded in November 2014. Unless otherwise footnoted, quotes and facts contained in the story are from these three sources.

4 Untitled story, Fitchburg Sentinel, March 4, 1938: 8.

5 Ogdensburg (New York) Journal, April 14, 1938: 6.

6 Rhode Island High School Sports, http://www.rihssports.com/RECORDS/BOYS/Baseball%20Records.html. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

7 “Sports in the News,” Newport Daily News, April 25, 1955: 12.

8 Rhode Island High School Sports, http://www.rihssports.com/ALL%20STATE/PAST/BOYS/BASEBALL/BASEBALL%20ALL%20STATE%201917.html. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

9 The Daniel Webster National Scholarship, the most prestigious freshman scholarship awarded by Dartmouth. Greg Johnson, “Local Pitcher Art Quirk Honored,” The Glastonbury Citizen, July 25, 2002: 2.

10 Had Quirk accepted the $30,000 offer, the Cubs would have been required to carry him on their major league roster for two years, per the major league “bonus rule” in effect at that time.

11 “Sports in the News,” Newport Daily News, May 21, 1957: 12.

12 Ernie Roberts, “Quirk Wins Pro Scouts Praise for Clutch Job Against H.C.,” Boston Daily Globe, April 21, 1958: 20.

13 Holy Cross was the NCAA champion in 1952 and advanced to the NCAA playoffs in 1954 and 1955. Their cumulative winning percentage since 1952 was over .800.

14 Roberts, “Quirk Wins Pro Scouts Praise for Clutch Job Against H.C.”

15 Barry was a Holy Cross graduate and 11-year MLB veteran. He played for the Philadelphia Athletics and Boston Red Sox, serving as player/manager for Boston in 1917. Barry coached Holy Cross from 1921 to 1960, with over 600 wins and a winning percentage over .800.

16 This reflection was provided by Dick Hoehn, Dartmouth Class of 1959, in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, March/April issue, Page 50, https://dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/class-note-1959-34 . Last accessed January 4, 2022.

17 “Most Valuable,” The Ogden Standard Examiner, June 19, 1958: 11A.

18 This contract offer, referenced in The Sports Illustrated profile, has sufficient additional detail to support its being a second $30,000 offer from the Cubs. The first $30,000 offer, after high school, was discussed among the Quirk siblings in a 2014 audio supporting its being a separate event.

19 Bill was a 1962 Dartmouth graduate and played center field for the Big Green in 1960 and 1961. He played 47 games and hit .189, with 28 hits in 148 at bats. He also played in the Cape Cod League in 1963 for Orleans according to the February 1964 Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. The Cape Cod League does not have detailed team records for 1963, https://archive.dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/article/1964/2/1/1962 . Last accessed January 4, 2022.

20 In his three years at Dartmouth, Quirk hit .200 with 16 hits in 80 at bats, with 5 doubles and 12 RBIs.

21 “Cape League Taps Star Pitchers of Past As Honorary Captains for All-Star Game,” https://capecodbaseball.org/news/asgnews/index.html?article_id=289. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

22 He is possibly 11th in innings, eight innings behind 10th place. Quirk compiled his career totals in three seasons covering 61 games, about 20 games per year. Since 1968 only two non-Covid seasons have had less than 30 games, https://dartmouthsports.com/sports/2018/7/3/589377.aspx?id=757. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

23 Associated Press,“5 Big League Clubs Are After Quirk,” Newport Daily News, June 5, 1959: 8.

24 “Sox Move on to San Antonio,” The Amarillo Globe-Times, June 29, 1959: 12.

25 The Amarillo Globe Times reported Gold Sox had back-to-back doubleheaders and Quirk was to pitch against San Antonio. The Sports Illustrated said there were four doubleheaders in four days and Quirk pitched against Corpus Christi.

26 Dick Kranz, “Sox Lose Early Lead, Fall to Nuevo Laredo,” The Amarillo Globe-Times, August 6, 1959: 18.

27 “Quirk Makes Day Success,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1959: 35.

28 Dick Kranz, “G-Sox Win Again; Injuries Worry Staller,” The Amarillo Globe-Times, August 7, 1959: 9.

29 “Oilers Trip Sox Twice,” The Amarillo Globe-Times, August 21, 1959: 9.

30 Doug Brown, “Orioles Hatching Lofty Hopes for Hill Ace Pappas,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1960: 13.

31 Doug Brown, “Quiet Boy Art Quirk Pegged to Fill Lefty Gap on Orioles Staff,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1962: 31.

32 Brown, “Quiet Boy Art Quirk Pegged to Fill Lefty Gap on Orioles Staff.”

33 Doug Brown, “11 Oriole Farmhands Bid for Room at Top,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1961: 24.

34 Doug Brown, “Six Orioles Whizzers Load Guns in All-Out Assault on Soph Jinx,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1961: 24.

35 International League, The Sporting News, July 5, 1961: 31.

36 Brown, “Quiet Boy Art Quirk Pegged to Fill Lefty Gap on Orioles Staff.”

37 Walter L. Johns, “Orioles Art Quirk Brainy Bird, Record Shows,” Cumberland (Maryland) News, March 12, 1962: 6.

38 Associated Press, “Quirk Fast Learner as Orioles’ Rookie,” Denton Record-Chronicle, May 31, 1962: 10.

39 “Quirk Fast Learner as Orioles’ Rookie.”

40 Doug Brown, “Orioles Risk 62 Grand on 3 Longshots,” The Sporting News, December 6, 1961: 21.

41 Brown, “Quiet Boy Art Quirk Pegged to Fill Lefty Gap on Orioles Staff.”

42 “Quirk Fast Learner as Orioles’ Rookie.”

43 “Capsule Comments Pinpoint ’62 Eye-Poppers,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1962: 10.

44 Doug Brown, “Hitchcock Lamps Red-Hot Scuffle for 2 Oriole Berths,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1962: 19.

45 Gordon Beard, “Took College Man to Beat Belinsky,” Evening Times (Cumberland, Maryland), May 18, 1962: 12.

46 Doug Brown, “Robin’s Old-Fashioned Takeoff Fills Oriole’s Nest with Chirps,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1962: 18.

47 Pat Gillick e-mail, October 27, 2021. Although Gillick and Quirk were teammates only briefly in Rochester in 1962, they were both signed in 1959 by the Orioles and would have shared many weeks at the same spring training facility through 1962.

48 Quirk was the 26th MLB player from Dartmouth. The most notable prior players were Red Rolfe (1931-42, New York Yankees four-time all-star third baseman) and Jack “Chief” Meyers, a native American catcher (1909-17, New York Giants, Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves, three time top-ten MVP).

49 Until the late 1970s Burnside (Class of ’52) had the most MLB wins (19) by a Dartmouth pitcher since 1900. His record was broken by Pete Broberg with 41 in a career that ended in 1978. The record was broken by Jim Beattie (52 through 1986), Mike Remlinger (53 through 2006), and Kyle Hendricks (83 through 2021).

50 Bob Johnson and Burnside for Barry Shetrone, Marv Breeding and Quirk.

51 Mickey Vernon, “New Senators Simply Can’t Get to 1st Base,” Nashua Telegraph, February 6, 1963: 19.

52 “Cape League Taps Star Pitchers of Past As Honorary Captains for All-Star Game,” https://capecodbaseball.org/news/asgnews/index.html?article_id=289. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

53 Shirley Povich, “Brinkman Cuts Nat Gloom with Classy Fielding,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1963: 20.

54 “Springfield Hold Eastern Loop Lead,” Shamokin (Pennsylvania) News-Dispatch, June 1, 1962: 7.

55 Bob Addie, “Vet Ridzik a Rarity on Nat Slab Staff — His Arm Isn’t Sore,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1964: 32.

56 Associated Press, “Nat’s Hurlers Quit,” The News (Frederick, Maryland), February 23, 1965: 23.

57 John F. Steadman, “Cost of Building a Winner: $11.6 Million,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1967: 40.

58 After college Christopher worked for the Triple-A Colorado Springs Sky Sox in 1992 and 1993 running stadium concessions operations.

59 Special education laws ensured Kerri’s access to public education until she turned 18. In an ironic twist, in 1983, the Quirks again turned to the Connecticut courts to maintain state support of her services. This required Kerri to become a ward of the state, an agonizing procedure for the family. “They had to deliver to the judge all of this information about how essentially incompetent Kerri was,” said Kent.

60 Johnson, “Local Pitcher Art Quirk Honored.”

61 https://capecodbaseball.org/news/hofnews/?article_id=202 . Last accessed January 4, 2022.

62 Baseball Reference, https://stathead.com/tiny/qhzUW. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

63 https://www.horizonsct.org/about/newsletters-annual-reports-2/newsletter-spring-2015. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

64 This story, written by Dick Hoehn, appeared in the March/April 1959 Class Notes of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, https://dartmouthalumnimagazine.com/class-note-1959-34. Last accessed January 4, 2022.

Full Name

Arthur Lincoln Quirk

Born

April 11, 1937 at Providence, RI (USA)

Died

November 22, 2014 at Stonington, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.