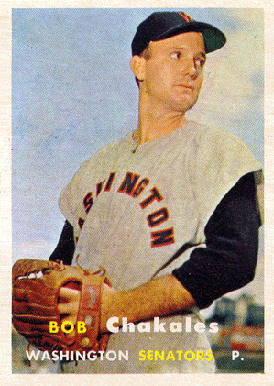

Bob Chakales

Major-league right-hander Bob Chakales was one of five sons born to Edward Peter and Blanche Wiggs Chakales – (sons in order: Robert, Charles, Dwight, and twins John and James). Bob was born on August 10, 1927, in Asheville, North Carolina. His mother worked in retail, selling women’s clothing, and his father – known as Eddie Pete – worked in a number of fields: the restaurant business, selling shoes, and as a brakeman with the railroad. Times were tough in the Depression and though both of Bob’s parents had jobs in Asheville, when Bob was in the fifth grade, the family moved to Dunn, North Carolina. That’s where Eddie Pete had one of the first Krispy Kreme doughnut shops, the company having opened in North Carolina in 1937.

Major-league right-hander Bob Chakales was one of five sons born to Edward Peter and Blanche Wiggs Chakales – (sons in order: Robert, Charles, Dwight, and twins John and James). Bob was born on August 10, 1927, in Asheville, North Carolina. His mother worked in retail, selling women’s clothing, and his father – known as Eddie Pete – worked in a number of fields: the restaurant business, selling shoes, and as a brakeman with the railroad. Times were tough in the Depression and though both of Bob’s parents had jobs in Asheville, when Bob was in the fifth grade, the family moved to Dunn, North Carolina. That’s where Eddie Pete had one of the first Krispy Kreme doughnut shops, the company having opened in North Carolina in 1937.

Two of Eddie Pete’s older brothers were born in Greece, Bob said. Eddie Pete himself was born in Pittsburgh, where the family seems to have first settled after coming to the US in 1902. Eddie Pete’s father, Peter, worked in confectionery manufacturing.

Bob hadn’t played any organized baseball in Asheville, but played a lot of true sandlot ball. “We used to stitch corncob parts together to make balls,” he said adding that he also spent some time reading about Babe Ruth. (Not long before Ruth died, Bob was able to meet the Babe at a special event and shake his hand.)

Baseball became more interesting to Bob after the move. “When I moved to Dunn, I found that baseball was a big deal. I was talked into joining the Kneepants League (a competitor to Little League for children aged 10 to 12).” Bob told his son James that his interest grew when he saw his name posted on the stats sheet at the local barbershop. “Every week the baseball stats were prominently displayed for everyone to see. I was hitting so well I could get a free lollipop anytime I wanted.” Clearly, this was a rewarding sport.1

Bob (or Chick as he was known in childhood) played as a third baseman in Dunn, and also played American Legion ball, again at third – the position where the team had the greatest need. Then in the final game of the season, when the games began to pile up and the team needed an extra pitcher. Bob’s coach asked him to pitch. He did well, winning his first outing, and was told, “Next year, you’re our pitcher.” Before the next year rolled around, the Chakales family moved again – to Richmond, Virginia, where Eddie Pete went into the restaurant business in a Greek restaurant. Before they left Dunn, Eddie Pete’s leg was crushed when a co-worker on the railroad forgot to switch tracks properly. While laid up, he thought more about the war. Eddie Pete tried to enlist but the damaged leg kept him with 4-F status.

The family pronounces their last name “Shackles” – though the Greek pronunciation would be slightly different, more like SHACK-a-lees. [I don’t know how the Greek pronunication might be. It might well start with a “ch” sound, and in his nickname “Chick”.] Bob would occasionally boast light-heartedly, “First there was Hercules, then there was Socrates, but along came Chakales, the Greatest Greek of all!”2

The American Legion team at Dunn wanted Bob back so badly that the mayor himself, Herbert Taylor, called and offered him room and board to return for another season. Once Bob agreed to return to Dunn, the mayor drove to Richmond and chauffeured him in a new Chrysler Imperial, which at the time was riding in style. Bob opened the American Legion season with a victory in an 18-strikeout performance. He wound up pitching Dunn into the state finals. He was named outstanding pitcher of the tournament.3

It wasn’t without the fright of his life, though, Bob told his son, James. The mayor owned a funeral home and that’s where Bob lodged. That was all well and good until a heavy downpour came. The funeral home had a tin roof and this was one of those storms “with raindrops so heavy you could weigh them.” It was during World War II, these heavy raindrops were pounding down on the roof so hard it sounded like bullets striking. He was upstairs and there were dead people laid out in the funeral home downstairs. Bob was so petrified he leapt out of bed, ran downstairs and saw one of the newly dead pop up from a table (this can happen with a combination of rigor mortis and post-mortem contraction of tissue and tendons.) Before Bob knew it, he just ran out of the funeral home, without a clear destination – just running across town during the rainstorm. Bob adds succinctly, “A funeral home is no place for a young person to spend their summer.”

Baseball wasn’t the only sport at which Bob excelled at the state level. James recalled, “Marble shooting was a big deal, especially in the South. I remember as a kid collecting marbles, and he would tell me, ‘Let me show you how you shoot marbles.’ Even then, he was 30 years older than me, he could lay a marble on the floor and he could fire a marble off his thumb and hit another marble every time.” When Bob was a youth, he went all the way to the top, winning the North Carolina state marble shooting contest. He might have gone further, but was too fearful of traveling out of state, so the runner-up was selected instead to represent North Carolina in later competitions.

While in Richmond, Bob met Granny Hamner, a fellow ballplayer his age and a future Philadelphia Phils Whiz Kid, who pushed for Bob to enroll at Benedictine High School, a small private boys’ Catholic school with strong sports programs. The headmaster, Father Dan, drove south to Dunn to scout Bob and decided Bob would be a great addition to Benedictine. Bob became the quarterback on the football team, and was named all-state in basketball and baseball. “We only had 16 in my graduating class and we competed against all the major high schools,” Bob said, “but we won a lot of state championships using kids from all four grade levels. Granny was a great friend and one heck of a ballplayer.”

It was a real boon to the family that Hamner had “recruited” Bob. His tuition was gratis – and even though it was a military school, Bob was not required to wear the military uniform. The sports uniforms were sufficient. The school apparently drew quite well, having good athletes on their teams. “Father Dan used to always say, ‘I am going to get my money out of you,’ which he did by assigning Bob menial tasks, and “when I was a senior he told me that he got all his money back.”

A news report in the Christian Science Monitor in 1944 said that Robert Chakales had struck out 99 batters in 69 innings for Benedictine High “despite a sore arm.”4 The following spring the Richmond News-Leader reported that a vote of coaches had named Chakales, a guard, as captain of the all-military-academy basketball team in Virginia.5 Bob was selected All-State in baseball, basketball, and football. On the ballfield that spring, he won eight games in a row, including a no-hitter, and led all Richmond batters in hitting with a .523 average.6

Young Chakales was offered scholarships to a wide variety of colleges across the South, but before accepting any he responded to a telegram from the Philadelphia Phillies, offering a tryout before general manager Herb Pennock at Shibe Park. He told Cleveland sportswriter Hal Lebovitz that Pennock had told him the Phillies would match any offer.

On June 4, 1945, an Associated Press dispatch reported that the Philadelphia Phillies had signed the 17-year-old to a contract with a reported $7,500 bonus and an additional $4,000 earmarked for his college education. There’s a good family story behind the signing. Bob’s son James tells it the way he heard it: “Connie Mack had come to Richmond from Philadelphia, and was in my grandfather’s home – my dad’s home – getting ready to sign Dad to a contract. He offered him $4,000, which at that time was still a lot of money. The phone rings, and Branch Rickey was on the other end. My grandfather answers the phone and says, ‘Mr. Rickey, hi.’ (Rickey) said, ‘We want to offer Bob a contract to play professional baseball for the Dodgers.’ (Branch Rickey wanted Bob for his hitting ability.). And he goes, ‘Well, that’s interesting. Connie Mack is here right now.’ Rickey replies, ‘He is? What’s he offering?’ The great Greek negotiator says, ‘He’s offered five thousand.’ ‘Just tell Bob to sign with us right now. $5,500.’ So my grandfather goes back and joins Connie Mack and my dad and says, ‘I’ve got Branch Rickey on the phone. He just offered $6,500 for Bob to sign with the Dodgers.’ And Connie Mack said, ‘Whoa. That’s a lot of money. I don’t think we can do that. I’ll tell you what, just sign right here and we’ll offer $7,000.’ My grandfather says, ‘OK, let me tell Mr. Rickey.’ He goes, ‘Mr. Rickey. Connie Mack just said $8,000.’ They went back and forth raising the signing bonus to $11,000 from the Athletics until Connie Mack sees what happening and says, ‘We are out of this business – you can sign with the Dodgers,’ and walked out the door. Then Branch Rickey felt his limit was reached so he backed out.” Bob ended up signing with the Phillies through representative Jocko Collins. Bob did get the money he wanted; $11,500, which at that time made Bob a huge bonus baby.7

It was most fortuitous that Rickey chose to call while Mack was in the home as Bob’s value was established. Although the Phillies provided Bob with college education money, he never did go to college: the college fund was, however, put to good use. The great Greek negotiator, Eddie Pete, used the $4,000 to pay off his mortgage. Bob told his dad he would earn that money back by playing ball. Instead of college, Bob went to Utica, New York. The Phillies first sent him to their Single-A affiliate, the Utica Blue Sox. He lost his first three games, though one was a 2-0 home loss to the visiting Hartford Senators. The powers that be decided to have the 17-year-old get his feet wet one level lower on the ladder and he went to Class B Wilmington, Delaware, where he pitched in the Interstate League for the Wilmington Blue Rocks. Bob posted a 13-5 record, despite a 5.06 ERA, and was one of the best batters on the team, hitting .327. He was listed as 6-feet-1 and 185 pounds. Between his high-school season and his first professional summer, Bob had 30 pitching decisions – a lot of pitching for someone who was still just 17 years old.

Despite all the innings he accumulated, Bob was booked for postseason baseball in October 1945, for the Richmond All-Stars against the touring Tommy Holmes major-league All-Stars team. His postseason didn’t last long. Though World War II was over, there was still a need to cycle in new soldiers, while letting those who had served come home, and on November 9, 1945, he passed his physical and was inducted into the Army. Fort Lee in Virginia was glad to have a pitcher going for its team, even though in his first outing, on April 10, 1946, Bob showed the rust from inactivity as he was pounded in a 10-1 loss to the Wilkes-Barre Barons, described in the press as “an ex-servicemen’s aggregation.” By early August, though, the Fort Lee Travelers had established themselves as state semipro champions and flew to the national semipro tournaments in Wichita. Chakales had been 7-3 with 119 strikeouts and was hitting well in the Army, too – .340. He was elected to the All-America semipro team. Branch Rickey hadn’t forgotten the young pitcher, but Philadelphia Phillies president Bob Carpenter declined a couple of offers Rickey made that December which were specifically aimed at acquiring Bob.

His service commitment complete, Chakales began pitching for Utica again in April 1947, first beating the Hartford Chiefs in May in the Connecticut state capital, 5-2. He shut out the Pioneers in Elmira, 1-0, with a three-hitter on June 3. Bob had mixed results throughout the season, but a highlight was the one-hitter he crafted against the Williamsport Tigers on September 5. Chakales later characterized the 1947 campaign to Hal Lebovitz: “Ah was as wild as a March Hare. Just wild. Ah don’ know what made me wild. I won seven and lost five.”8 His ERA was again over five runs a game, 5.36, and he walked 76 batters in 94 innings.

Chakales tried out with the Phillies in Clearwater during spring training 1948, and was again assigned to begin the season pitching for Utica, but hurt his arm trying to work a curveball. “I was trying to snap a curve and I snapped my arm. My arm was really sore. I told them about it and they said, ‘Keep throwing – it’ll work out.’ Instead it got sorer and sorer. I could hardly lift the ball.”9 The advice was not atypical for the day, and many pitchers found their careers cut short as a result. Chakales was 1-2 with Utica, but with a much-improved ERA of 3.71.

Once more, he was moved to a lower level and was sent to Maine, joining the New England League’s Portland Pilots in early June. A three-hit 12-0 shutout of the Lynn Red Sox on June 15 was noted by the AP. The Sporting News reported on his winning both halves of a doubleheader against Manchester on August 27, the first a one-hitter and the second after coming on in relief.10 For Portland he was 12-7 with a 3.16 earned-run average.

A scout working for the Cleveland Indians, Latimer “Laddie” Placek, saw Bob pitch a game for Utica that stuck in his memory. “I liked what I saw,” Placek told the Tribe’s front office (Laddie was their head scout in the state of Ohio). “He’s fast, he’s worth a gamble.”11 So the Indians pounced and took Chakales in the minor-league draft on November 15, 1948. Chakales was taken by Oklahoma City, part of the Cleveland Indians system. (Phils owner Carpenter did get back $3,000 of his bonus money as a result.)

In 1949, Chakales played with the Single-A Wilkes-Barre Barons into May and was advanced via option to Oklahoma City of the Double-A Texas League on the 14th. Despite the move, Bob spent most of the season pitching for the Barons, right into the championship game against the Binghamton Triplets in the Governors Cup finals on September 25. He pitched one-hit relief in that game, but the damage had already been done and Whitey Ford won it for the Triplets. It really hadn’t been that successful a season for Chakales. For Wilkes-Barre he was 6-10 with a 5.25 ERA. He blamed it on the sore arm he’d developed in ‘48 and it left him with a poor disposition. He acted out. “Ah became a playboy,” he said in the Southern drawl Hal Lebowitz attributed to him. “I learned how in the Army. I got out of shape.” Placek wasn’t pleased; he contacted Bob over the wintertime. “Laddie wrote about how he believed in me an’ how I was lettin’ him down. He wrote that he had more confidence in me than I had in myself.”12

The arm got better, and perhaps Placek’s letter supplied a little more motivation. Chakales became the main moundsman for the Barons in 1950 and threw the Eastern League title-clinching game on September 1 with a 4-2 win over Hartford. He was an all-star that year with a 16-5 record and a superb league-leading 2.04 ERA. Nine days later, the Indians announced that they’d obtained him from their Wilkes-Barre affiliate. The Barons easily beat Binghamton four games to one in the Governors Cup. After the season Chakales was named the top pitcher in the Eastern League.

Chakales reported to Tucson for spring training in 1951 with the Indians. Hal Lebovitz of the Cleveland News was much taken with the young ballplayer, calling him “a likable rookie with a friendly smile … as colorful as Dizzy Dean … something like a character in a Ring Lardner yarn.” He brought 10 suits and 17 pairs of pants to camp, 25 shirts, and “at least 50 pair of socks.” Asked why he was lugging around so much clothing with him, he drawled, “Man, I didn’t come hear just for a visit. I came here to stay.” 13 He was touched up for a wind-blown double by Yankees rookie Mickey Mantle, in relief of Early Wynn during the exhibition season’s first game, but got his feet wet. At the end of March manager Al Lopez said he felt the Tribe bullpen could make a difference in 1951 and cited Al Olsen, George Zuverink, and Bob Chakales as joining the veterans Steve Gromek, Sam Zoldak, and Jess Flores.

Chakales debuted in Cleveland on April 21, 1951, giving up one hit in one inning of work, the third pitcher in a lost cause as Ned Garver of the Browns beat the Indians, 9-1. His first start came on May 6, a 4-2 win over the visiting Washington Senators. He’d started off a little wild, granting seven bases on balls in the first four frames, but settled down to win the game. On May 13 Bob had been added to the starting rotation as a fifth or sixth starter. He contributed with the bat with what proved to be his only big-league home run in a game against the White Sox that ended in a 4-4 tie when time ran out in the 10th inning, conforming to an agreement reached in advance that allowed the Indians to make their train. On Memorial Day he had his first complete-game win, despite giving up nine hits and six walks; he’d parceled them out judiciously. He drove in two runs as the Tribe took the Tigers, 3-1. Chakales was a good batter; over his four seasons with the Tribe, he hit .353 in 34 at-bats. After his seven seasons of major-league ball, he held a .271 average.

Bob’s best major-league pitching effort, a 2-0 four-hit shutout of Detroit, came on the same day that Bob Feller no-hit the Tigers in the first game of a doubleheader. Bob laughed as he told his son James that when he did something that was headline-worthy – Feller threw a no-hitter on the same day. The Tigers got some revenge five days later against the Tribe, rolling up 13 runs (more than they’d scored in their first 11 games of the season when facing the Tribe), including six hits and four runs off Chakales in relief of losing pitcher Bob Lemon.

Chakales’ last start of 1951 came on August 22, when he “blew up completely” in the seventh, allowing three more runs to the Senators, leaving a game down 5-2; the Indians won it in 14, 6-5. Had they made the World Series, he’d been on the eligible list, but the Indians finished second; after the season, he earned a full share of the second-place money. His name came up in trade talks over the winter – catcher Birdie Tebbetts raved about him – but on February 2, GM Hank Greenberg announced that Chakales and Lou Brissie had re-signed, both with increased pay. Greenberg had earlier assured Chakales that he would not be traded and would work every fifth day in the Tribe’s rotation. That still didn’t prevent the Indians from trying (in vain) to spring Sam Mele free from the Senators by dangling Chakales and Bob Kennedy in front of Washington in early March. A month later the Senators came back offering lefty Mickey Harris for Chakales. No go. During the offseason, Bob had worked as player-coach of the Dixie Containers basketball team in Richmond.

In spring training of ’52, Chakales told The Sporting News correspondent in Tucson that by his own assessment, he had improved 15 percent over the year before! He explained, “I did it with my mind.” Chakales went on to say that manager Al Lopez had told him he needed to work on his curveball if he wanted to guarantee his future with the Indians. He asked Tebbetts how to better his curveball, and Birdie answered with one word: “Think.” So, Bob said, “I’d lie in bed at night and just think about my curve. The trouble was I’d let it go too close to my chest. I kept thinking about releasing the ball at arm’s length and when I came out here for training I threw the curve just the way I thought about it.” Birdie had inspired success via visualization.14

Chakales had just one start for the Indians in 1952, winning the next to last game of the season. He’d spent most of the year in Indianapolis, playing for the Indians’ Triple-A club. The only drawback, he said, was that he’d planned to get married in Richmond the next time the Indians had visited Washington to take on the Senators. Now it was going to cost him extra to travel from Indianapolis to Richmond to keep the appointment. The marriage to Anne Mackenzie came off, on June 7, though manager Gene Desautels hit him with a fine for reporting back late.15 Chakales labored with a 5.18 ERA in Indianapolis. He was recalled nonetheless on September 2. His first game back was the following day, and he loaded the bases in the sixth. Lou Brissie relieved him, and Brissie’s first pitch was hit for a grand slam by Detroit’s Don Kolloway. In a season wrap-up, sportswriter Ed McAuley commented from Cleveland that Chakales was the youngster most likely to succeed in 1953. The Indians did broach a trade with Boston, a massive one involving Dale Mitchell, Ray Boone, Bobby Avila, and Chakales to the Red Sox for Dick Gernert, Dom DiMaggio, and Billy Goodman, but Red Sox general manager Joe Cronin replied, “I wouldn’t give Billy Goodman for the entire Cleveland team.”16

In 1953, Bob opened the season with the big-league ballclub and played most of the year with the Indians, though appearing in only seven games before he was optioned to Indianapolis on July 23, his record with Cleveland being 0-2 with a 2.67 ERA in 27 innings of work. He got into only 11 games with Indianapolis, and was 4-2 with a 3.91 ERA. He was recalled on September 9 but saw no further action. That winter he pitched for Gavilanes in the Venezuelan League.

The 1954 spring training season started off a little rocky, and in the second game of the exhibition season, Chakales saw his infielders commit errors on four consecutive balls. He summoned them to the mound, and then tried to lighten the mood by asking if the fix was in. The Indians won the game, 23-10, over the Giants.17 However, Bob was ready for the season.

Chakales opened the 1954 campaign in Cleveland, where he helped the Indians off to the best season in baseball history (111 victories in a 154-game season). He picked up his first decision of ’54 for the Indians on May 16, winning the first game of a doubleheader over the Athletics. He won again, beating the Red Sox on May 18.

Bob’s time with the Indians, highlighted by a 2-0 record and an ERA of 0.87, made him more marketable. The Indians went to the World Series in 1954, but without Chakales. On June 1 Cleveland traded their 26-year-old pitcher to the Baltimore Orioles for Vic Wertz, in a deal that has been considered the blockbuster trade of 1954.18 He left a first-place team for a team in last place at the time of the trade. Wertz reportedly had a strong dislike for batting in Baltimore, which pushed the Orioles into seeking a trade. Looking back on things, it seems like an uneven swap, but Chakales was considered an ambitious young pitcher with great potential. Orioles general manager Art Ehlers believed that Bob could become a regular in their starting rotation. He had not been able to get enough work with the Indians. They had too good a team. With such a superior staff (Wynn, Lemon, Garcia, Houtteman, and Feller), he just wasn’t going to have enough opportunity to break into Cleveland’s rotation. He felt a little regret 50 years after the fact: “I was never as sharp and I could be, since pitchers went the distance back then. When I pitched a lot, I was good; when I didn’t, I was not. I think I got out of shape for a while, too, just waiting for ‘the call.” 19 Indians manager Al Lopez knew how hard it had been since Chakales broke in for him to crack the rotation; the 1951 and 1952 teams had three 20-game winners on the staff. “With any other major-league team, he would be a starting pitcher,” Lopez allowed.20

Given a start for the Orioles on June 4, Chakales lasted but 2? innings, giving up four earned runs and losing to Philadelphia. He started six games for the Orioles and relieved in 32 others – winning in back-to-back extra-inning relief jobs on June 26 and 27. There was an odd occurrence in Detroit on July 11. Al Aber of the Tigers had a perfect game going and had set down 17 Orioles until Chakales singled in the sixth. When Cal Abrams followed with a double, Bob had scored – until he was ruled out for failing to touch second base in his haste. Inning over. The final was 2-1, Tigers. On August 6 Chakales faced Ted Williams at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium with the score was tied in the top of the 10th. With two outs, Ted came to the plate. Bob’s son James recounted the story his father told him: “Ted was on a hot streak but Bob had gotten him out earlier. The manager called time and asked Bob if he wanted to walk Ted; of course he said no. Bob had Ted 0-2 in the count with two fastballs. He threw a low inside slider as a waste pitch and Ted got under it and popped it up. Bob was walking off the mound and glanced back to see the right fielder drifting to the foul pole. The lazy popup went over the fence just out of the reach of the right fielder’s glove. Bob was so mad he chased Ted Williams around the bases calling him every name and expletive that came to mind – the one that could be printed was: “You lousy, cheap-shot artist, you lucky bum, you will never get another hit off me.” Later, when Dad was traded to the Red Sox, he asked Ted if he was mad at him for chasing him around the bases and for what he said. Ted just gave that smirky smile of his and said, he had forgotten all about it.”21 With Baltimore, Bob was 3-7 in 1954, though his 3.73 ERA was slightly better than the team average.

On December 6 he was packaged in a seven-player trade. He went from the Orioles to the Chicago White Sox with infielder Jim Brideweser and catcher Clint Courtney for pitchers Don Ferrarese and Don Johnson, catcher Matt Batts, and infielder Fred Marsh.

Chakales got very little work in the first part of 1955, and then he and Courtney packed their bags once more – on June 7 they were again traded as part of a threesome, this time joining outfielder Johnny Groth – all three packed off to Washington for one man: outfielder Jim Busby. In his short time with the White Sox, Bob had thrown 12? innings and given up 11 hits and six walks, but only two runs (1.46 ERA). After announcing the swap, Chicago general manager Frank “Trader” Lane enigmatically characterized Chakales as a “pitcher of parts.” 22 It was a big gamble for Lane. For Chakales it was another trip down the standings. The White Sox spent some time in first place that summer, and the Senators spent time in the cellar. Chakales was hit hard on the left knee by an Enos Slaughter liner in mid-July but picked up his first win of the season, and was back in action a week later.

Washington manager Chuck Dressen made Bob his main man for relief, but he struggled. Over the wintertime, Bob explained to Washington Post writer Bob Addie that he’d felt tired throughout the summer of 1955. “My arm was dead,” he said, “and I felt as if I was a sleepwalker most of the time.” A thorough physical included a fluoroscope examination that revealed the cause. “I was oozing poison from my appendix. They cut it out and I began to feel like living again. I did a lot of throwing this winter to test the arm and it feels great.”23

Addie’s interview with Chakales wasn’t the only news the pitcher generated during 1956 Grapefruit League play in Orlando. A later column explained how Bob was driving an electric golf cart on the Dubsdread Country Club course when, negotiating a narrow wooden bridge near the eighth hole, the cart tipped over and dumped fellow right-hander Hal Griggs in the drink.24 Bob had fully recovered from the appendectomy but pulled a muscle in the springtime; nonetheless, he started the 1956 season well. Throwing an unanticipated 7? innings of scoreless three-hit relief against his old Chicago teammates on May 3 earned Bob his second win of the season, just four days after 5? innings of one-hit relief against his former Orioles mates gave him his first victory, on April 29. He was, at age 28, the second oldest on the Senators’ staff.

On May 8 Chakales stumbled, giving up five earned runs while recording only one out, but on the 11th there was another lengthy relief stint – six innings of two-hit ball against the Red Sox. His longest effort was 10 innings of five-hit relief in a 17-inning loss to Kansas City on May 23, but Bob was long gone before the denouement. By early June he was considered the “surprise performer” with a 1.94 ERA through his first 14 outings. He pulled a tendon in his elbow, however, and suffered a sore arm for much of the year. He soldiered through the season, however, appearing in a club-high 43 games.

Asked about what seemed to be an unusually high number of sore arms reported in the press, Chakales forthrightly admitted in 2009 that some of them may have been a little manufactured for popular consumption via the newspapers: “My junior year in high school, I probably over-pitched. Pitched a lot. I had one sore arm in the minor leagues, and had a couple after leaving the Indians. I didn’t have many sore arms in the big leagues. Let me tell you, I told a lot of people I had a sore arm when I was with Cleveland because I was young and embarrassed I wasn’t playing. I thought I should have been playing; I had to have a reason. I wasn’t going to tell them I wasn’t good enough, or whatever. I wasn’t going to say anything bad about the management. I just said my arm was sore.” These were still the days when there was always someone ready to take your place.

Over the wintertime, Bob opened his own restaurant in Richmond, called Blair’s. It was his second venture in the field, having owned and operated one on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the winter of 1955. Another job Bob had done fairly early was – as he put it – to take an ax and “cut trees down in front of billboards. I thought it was the best way to work on my swing and keep my strength.” The work was for Ted Turner’s young company, Turner Outdoor Advertising. He also sold automobiles, as did a lot of ballplayers.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower threw out the ceremonial first pitch of the 1957 season, and Bob Chakales took over from there, pitching on Opening Day against Baltimore. He threw seven innings and gave up four runs, but left with the lead. He himself had driven in the fourth and fifth Senators runs with a two-out triple in the bottom of the fourth. The O’s beat the Senators’ Camilo Pascual in the 11th inning, and to his credit, Ike stayed for the whole game. Chakales didn’t quite last the month, though. On the 29th, the Senators sent him and pitcher Dean Stone to the Red Sox for infielder Milt Bolling, pitcher Russ Kemmerer, and outfielder Faye Throneberry.

Red Sox pitching coach Boo Ferriss was high on Chakales. “We were fortunate to add a pitcher of Chakales’ experience,” he told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “He has the stuff and he has a book on the hitters. He has that valuable know-how. He knows what he’s doing out there. The only real bad pitch on his record is that three-run homer by Frank House in the second game at Detroit last week. But I’ll tell you something about that pitch. It was a waste ball. The count was nothing and two and Bob threw one too high for a strike. House’s strength is a pitch at waist height or lower. But this time, for some reason, he went after the high pitch and hit it into the seats. It will probably never happen again.”25

Bob got to see part of Ted Williams’s amazing .388 season, in the year Ted turned 39, but not the whole of it. On the first of August, the Sox purchased 16-7 Murray Wall from Dallas and optioned Chakales to their San Francisco Seals farm club. There was one odd incident in Sacramento, when the umpire ordered Bob to change his pants during a game. It was in the midst of a three-hit shutout he was administering to the Solons and the Sacramento manager complained that Bob kept “going to his pants” as though there were a foreign substance there that he was using to benefit his pitching; Bob was deemed clean and finished the shutout. After the Coast League season ended, he was brought back to Boston, where he appeared in one final game, on September 17. Ted Williams pinch-hit a game-tying homer in the bottom of the eighth, Billy Klaus drove in the go-ahead run, and Chakales earned the save with a 1-2-3 top of the ninth. In what proved to be his final major-league appearance, Bob actually took Ted Williams’s place. Pinch-hitter Ted had homered (the 452nd of his career) deep into Fenway’s right-field seats, tying the game, and Chakales took his place in the batting order, throwing the ninth inning and setting down the three men he faced. During Bob’s year at Boston, he and Williams became close. Bob often stayed in the hotel room registered for Williams to shield Ted from the media. Bob and Ted continued to see each other after they had retired from baseball. During five straight years in the 1970s, Bob and Ted met during the Preakness horse race in Baltimore. At his death Bob still had a book Ted gave him, The Art of Pitching, with an inscription from Ted: “Bob, I always loved it when you were pitching … because I knew I’d get a hit, your friend Ted.” Bob often teased Ted about leaving the bases loaded twice against him. Before memorabilia was big, Ted signed his official Genuine Louisville Slugger with his name engraved and gave it to Bob. Not knowing the value of the bat, his son James broke the gift from Ted in a sandlot game. “All Dad said was, ‘I wish you did not do that, Ted gave me that bat.’ Nothing else was said again.”

On January 14, 1958, the Red Sox announced the outright sale of Chakales to Minneapolis, which had replaced San Francisco as Boston’s top farm club. After he gave up 13 earned runs in 17 innings, laboring under illness, Minneapolis had seen enough, and sent Chakales away – but for Bob it was a bit of a treat to find himself sent to his hometown team, the Richmond Virginians, part of the Yankees’ system, managed by Eddie Lopat. On June 8, just one Sandy Amoros single in the second inning deprived him of a no-hitter against Montreal, one of four shutouts by Bob during the season. He still hoped to return to the majors, and Lopat said there were several teams that could well use him. Chakales was only 30, and declared, “Lopat has taught me more about pitching than I ever knew.” He was telling Chakales to be more aggressive, in the strike zone, and not give the hitters a chance to relax. Though he said he felt the best he’d felt in three seasons, he served out the full year in the minor leagues.

That December Richmond sold him to the Toronto Maple Leafs. Chakales became involved in strike talk, as one of two player representatives for the International League. With seven seasons of major-league experience, he was selected to represent the IL players, who were angling for the implementation of a pension plan, and the 160 members of the International League Baseball Players’ Association were being urged to neither sign their 1959 contracts nor report to spring training unless the owners agreed to submit the proposal to arbitration or at least discuss it. Chakales was outspoken on the subject: “They say minor-league ball is deteriorating and no wonder. There is a great deal of discontentment in the league. All the players live for is the first and 15th of the month to collect their pay checks. Most of them don’t earn enough to support their families and are looking for outside jobs to supplement their income. Added to that, they have no security.” They were looking to create a pension that would entitle the players to collect $59 per month in their old age. “I thought I could benefit as well,” he said in 2009. “I went to New York with a lot of confidence and left knowing that Major League Baseball was a huge powerful organization and the minor leaguers had no chance. Too much money, power, and influence.” Asked if it might have hurt him to have been a leader, he felt it may have. “There was not a strike, but I left work to negotiate. In effect, I was the only one who went on strike. I still had a lot of good pitching ahead of me, but could not make it up again. I can’t say it hurt me; although I felt I was still better than some of the guys who were still pitching.” With 16 seasons of professional baseball under his belt, and the one year – 1946 – he spent in the Army, he admitted to being a little steamed. “I was mad then, but got over it after a while. I loved the sport and felt I never got to show I would have been a 20-year player.”

Chakales’ opportunities may have been limited but he wasn’t blackballed from baseball entirely, and he got in a fairly full season for the unaffiliated Toronto Maple Leafs in 1959 (13-10, 4.04). The Indians took on Toronto as their Triple-A affiliate in 1960, and Bob was back in the Cleveland system, going 9-3 (3.74). In 1961 he split the season, 3-1 for Toronto and then 4-3 for the Hawaii Islanders (in the Pacific Coast League, affiliated with the Kansas City Athletics.) The 1961 season was his last in professional baseball. His last time pitching against major leaguers was in an exhibition game in Toronto on July 14, 1961, when he pitched a 3-0 three-hit shutout against the American League California Angels.

In the minor leagues, Chakales was 113-73 with a 4.08 earned-run average. As in the major leagues, he’d been used more as a reliever than a starter, with 162 of his 295 appearances coming in relief roles, but most often in long relief (over his minor-league career, combining starts and relief roles, he averaged an impressive five-plus innings a game). In the majors, Bob was 15-25 (4.54 ERA), starting 23 of his 171 games and averaging just a little over 2? innings per appearance.

After baseball Bob sold insurance for a local agency in Richmond, Markel Insurance. The Markels, he said, were great sportsmen and very good businessmen. At the time he retired from playing ball, they owned part of the Richmond Virginians. Bob loved golf, and thought about going pro, “but my 1 handicap was nothing compared to those greats. I was in the beer league and they were playing for champagne.”

One of his uncles, Broaddus Wiggs, told him about a new golf course concept called Lighted Night Golf – Par 3. They contacted the United States Golf Association, found out how to register as a contractor and built a par-3 course in Richmond. A general contractor from Charlotte, Ray Costin, heard about the course and reached out to Chakales. The two formed a partnership and began to build par-3 courses. Then requests came for Bob to build championship courses; he started with a nine-hole championship course and then went on to build course after course, in the end building nearly 200 golf courses and becoming president of the Golf Course Builders Association of America. Chakales built the original TPC Sawgrass Course in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. Presumably, he designed wider bridges over water hazards than the one he’d failed to successfully negotiate in Orlando in the spring of 1956!

Golf course construction was a busy life, with a lot of travel. “I was gone more than I wanted to be. I was good at what I did, but fearful I would not get that next job – so fortunately I had many offers so I kept my plate full.” Like many busy men, Chakales had some regrets at missing a few too many family events, but considered himself blessed to have “five wonderful children (Sandra, Robert, James, Dabney, and Susan) and a patient and loving wife who is still as beautiful as the day I met her.”

Three of Bob and Anne’s five children continued with athletics after high school. Bob Jr. swam at the University of Alabama with Olympic Silver Medalist Jack Babashoff, Dabney played tennis and basketball at Meredith College, and James played baseball for Bobby Richardson at the University of South Carolina. James followed in his father’s footsteps and came close to playing professional ball as well. Bob recalled that Boston Red Sox scout Mace Brown was one of the scouts who wanted to sign James out of high school (he witnessed James throw a 12-inning, one-hit, 20-strikeout performance in the American Legion State Championships) but Bob said, “No. James is going to college – something I did not do.” James went on to throw a couple of no-hitters in American Legion ball and then played with Mookie Wilson and other All-Americans on teams that made it to the College World Series final game twice (1975 and 1977).

Bob Chakales died on February 18, 2010, in Richmond. He was 82 years old. He is buried in Westhampton Memorial Park in Richmond.

This biography is included in the book “Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Bob Chakales, James Chakales, and to Debbie Matson of the Boston Red Sox.

Notes

1 Communications with Bob and James Chakales via telephone and e-mail, July 2009

2 E-mail communication from James Chakales, July 17, 2009

3 Hal Lebovitz, “‘Shackles’ Binds Tribe Foes,” Baseball Digest, August 1951.

4 Christian Science Monitor, June 14, 1944

5 Washington Post, March 16, 1945

6 Diamantis Zervos, Baseball’s Golden Greeks: The First Forty Years, 1934-1974 (Aegean Books International), p. 94

7 Interview with James Chakales, July 17, 2009

8 Hal Lebovitz, op. cit. Lebovitz seemed fascinated with Bob’s regional accent, but Chakales had better communication skills than Lebovitz attributes to him – and he even worked for a while as a temporary sports columnist in Richmond when the regular writer, Lawrence Leonard, was on vacation or sick.

9 Zervos, Baseball’s Golden Greeks, op. cit.

10 The Sporting News, September 8, 1948

11 Zervos, Baseball’s Golden Greeks.

12 Hal Lebovitz, op. cit.

13 The Sporting News, April 4, 1951

14 The Sporting News, March 19, 1952

15 The Sporting News, June 25, 1952

16 The Sporting News, December 31, 1952

17 The Sporting News, March 17, 1954

18 See David Nemec, et. al., The Baseball Chronicles, Publications International, p. 288.

19 Communication from James Chakales, July 17, 2009

20 Zervos, Baseball’s Golden Greeks, op. cit., pp. 97, 98

21 E-mail from James Chakales, August 10, 2009

22 New York Times, June 8, 1955

23 Washington Post, February 25, 1956

24 Washington Post, March 4, 1956

25 Christian Science Monitor, May 7, 1957

Full Name

Robert Edward Chakales

Born

August 10, 1927 at Asheville, NC (USA)

Died

February 18, 2010 at Richmond, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.