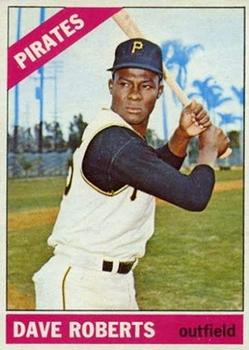

Dave Roberts

Four men named Dave Roberts have played major league baseball. David Leonard Roberts, who appeared in 91 games in the 1960s for the Houston Colt .45s and Pittsburgh Pirates, is probably the least known, at least in the United States.1 But across the Pacific in Japan, that Dave Roberts is by far the best known – beginning at the age of 34, he became one of the first gaijin to truly become a star in the Land of the Rising Sun.

Four men named Dave Roberts have played major league baseball. David Leonard Roberts, who appeared in 91 games in the 1960s for the Houston Colt .45s and Pittsburgh Pirates, is probably the least known, at least in the United States.1 But across the Pacific in Japan, that Dave Roberts is by far the best known – beginning at the age of 34, he became one of the first gaijin to truly become a star in the Land of the Rising Sun.

When Roberts retired as a player in 1973 after seven years in Japan, he had logged over two decades in professional baseball in an unlikely baseball odyssey that had taken him from his native Panama to play in nine countries plus Puerto Rico.2 He broke into professional baseball in 1952 at 19 years of age as a Black kid from Panama playing in a foreign country, only five years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line in organized baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers. It took Roberts ten long years to get a chance to play in the big leagues, and along the way he encountered racism, both implicit and overt, at every turn. But, although he ultimately had to ply his trade in Japan and not his adopted United States, he lived his life seemingly without a trace of bitterness.

Dave Roberts was born on June 30, 1933 in Panama City, Panama. His father, who went by Bob, was a steam fitter on the Panama Canal and was originally from Barbados in the West Indies.3 His mother, Gwen, also had a West Indies heritage but was born in Panama. Because his father worked for the Panama Canal Company, he was able to move the family to the Canal Zone where the schools were better and were taught in English. As a result, Dave grew up speaking Spanish and English.4

Roberts was taken with baseball at an early age, catching games on the radio from Cuba and listening to the Caribbean World Series. He sent away to the States for Joe DiMaggio’s Lucky to be a Yankee autobiography, which he treasured for years, and devoured the occasional baseball articles in old copies of Collier’s magazine. When the New York Yankees played a spring training game in Balboa, Panama, in 1946, the 12-year-old Roberts skipped school with a couple of buddies and went to the ballpark. They climbed a wall and watched from the roof of a laundry as DiMaggio hit arguably the longest home run of his career, out of the park and over the trees behind the fence.

The following spring, 1947, Roberts saw Jackie Robinson play from the same perch. That was of course the year Robinson broke the color barrier. The Dodgers trained in Cuba and played some exhibition games in Panama that year to avoid the overt racism of the Deep South. When Roberts saw Robinson play for the Dodgers he announced to his friends that “I’m going to be a major league ballplayer.”5

Roberts also identified with Larry Doby, who broke the color barrier in the American League later in 1947, since Doby was an outfielder who batted left, just as he did.6 By the time Roberts was 14 he was good enough to play with grown men on the Gamboa town team. When he was a junior at La Boca Occupational High School he began playing in the Liga Amateur de Panama (the Panama Amateur League) for the company team sponsored by Café Duran, the largest coffee producer in Panama.

There he caught the eye of Chet Brewer, a veteran Negro League pitcher who was spending the winter playing and managing in Panama’s professional winter league. Brewer was impressed with the power that the 148-pound Roberts generated from his strong wrists and exceptional bat speed. Brewer was to manage a team in the Class C Southwest International League that summer of 1952, and signed the 18-year-old Roberts to his first professional baseball contract.

Brewer’s team began the 1952 season as the Riverside-Ensenada (California-Mexico) Comets. It was supposed to be an all-Black squad that would play home games on both sides of the border. But by the time Roberts finished his junior year of high school and reported, the team had moved to Portersville, California, and was integrated.7

Roberts’ first professional game was against the El Centro Imps and Brewer put him in the lead-off spot to take advantage of his considerable speed. As he stepped in to face Imps pitcher Pete Castro, Mitchell Francis, the Imps large African-American catcher, asked him if he was a rookie. Following Brewer’s instructions, Roberts said, “Naw, I’ve played before.”

Francis then said, “Well, if you’ve played before, will you do me a favor? Will you get out of the batter’s box so my pitcher can warm up?”

Roberts sheepishly backed out of the batter’s box but when the pitcher was ready, stepped back in and lined the first pitch to left-center field for a base hit.8

Under Brewer’s wise tutelage, Roberts batted .314 in 80 games in his first professional season and played in the league’s two All-Star games. And even though he was playing in a league in the western United States, he got his first taste of the racial discrimination that plagued American society. In places like Yuma, Arizona, and even Las Vegas, some restaurants refused to serve people of color.9

The Porterville team disbanded on August 1, 1952, and Roberts returned to Panama for his senior year in high school. He played that winter for Chesterfield in the Panama winter league and hit a lead-off inside-the-park home run that sent his club into the Caribbean World Series in Havana, Cuba, as the representative from Panama. There, after he smashed two doubles against the Cuban team, scouts from both the Dodgers and Senators wanted to sign him, only to learn that he was already under contract with the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League, which had purchased him from Porterville.10

Roberts graduated from high school and reported to the Padres spring training in 1953 in Southern California. Although he performed well early in camp, manager Lefty O’Doul told Roberts that because the Padres had so many high-salaried veterans on the team, they were sending him to the Tampa Smokers in the Class C Florida International League. After reporting to Tampa, Roberts ran into Jackie Robinson at the only hotel that allowed blacks. Robinson was in town for an exhibition game with his Brooklyn Dodgers against the Cincinnati Reds.

Robinson told Roberts, “Son, you’re going to have to be a helluva ballplayer to stay here.”11

Robinson was referring to Ben Chapman, the highly bigoted manager of the Smokers. As manager of the Philadelphia Phillies when Jackie broke baseball’s color line in 1947, Chapman had been infamously vicious in his verbal assaults on Robinson.12 Unfortunately, Robinson was correct. Although Roberts was hitting .358 well into spring training, Chapman announced one day that he was sending Roberts back to San Diego because he had no room for him in Tampa.

Before Roberts could even depart for San Diego, he got a letter from the Padres advising that he was being released even though he had hit well above .300 all spring. That left the 19-year-old Roberts trying to decide whether to simply go back to Panama or try out for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues, who were supposed to be traveling through Tampa in a few days. However, Lenny Pecou, a French-Canadian outfielder on Tampa’s roster, interceded and got Roberts a spot with the Grand Forks (North Dakota) Chiefs in the Class C Northern League.

At the time, Roberts wasn’t sure if Grand Forks was a state in the union or a town, but he reported to the club in early April, when it was still quite chilly in North Dakota. He was the first Black player to play for Grand Forks and one of the very few Blacks in town, eliciting stares wherever he went. Although he had trouble adjusting to the cold weather, he still hit .269 for the season with 15 home runs and 88 RBIs in 125 games. The year was a lonely one for Roberts, who had no real social life in Grand Forks. On game days, his normal routine was to walk from his rooming house to the library where he would read the newspaper or a book, then get a sandwich and walk to the ballpark for the game.13

He played well enough with the Chiefs that the Baltimore Orioles bought his contract in the off-season. But after minor league spring training in 1954 in Thomasville, Georgia, the Orioles sent him back to the Northern League to play for their affiliate, the Aberdeen (South Dakota) Pheasants. Although it was Roberts’ third year in Class C, he was still only 21 years old. He showed his true potential by slamming 33 home runs, driving in 114 runs in 135 games, hitting .297 and making the league All-Star team as a first baseman.14 He starred in the All-Star game, going 2-for-4 with a home run and three RBIs to propel his squad to a 13-2 victory.15

Roberts’ 1954 performance earned him a promotion all the way to Double A with the San Antonio Missions in the Texas League for 1955. After a fast start Roberts slumped, due in part to the prevailing wind that blew in from right field in the Missions ballpark which turned his long blasts into warning track outs. For most of the season, Roberts was the only Black player on the team as, indeed, there were only a handful of Black players in the league. Jim Crow bigotry was alive and well in Texas and, although the San Antonio fans were relatively benign, Roberts faced excruciating racial taunts on the road and sometimes from opposing teams.

Once in Shreveport, Louisiana, the racial heckling was so bad that Howie Fox, a 6’3” teammate and veteran big-league pitcher who was winding down his career, went over to the stands and told a group of hecklers, “If you say one more word, if you get on him one more time, I am coming into the stands.” He then said, “I’m gonna pinch your heads off.”16

Against Beaumont that summer, Roberts hit home runs during his first two trips to the plate. The next time he came up, Mickey Livingston, the Beaumont manager, went to the top of the dugout and yelled at his pitcher, “Hit that [n-word] in the head. I mean it, hit that [n-word] in the head.” And sure enough, the first two pitches were very high and tight.17

Most of his teammates on the Missions would have little to do with him and Roberts later remembered only Stan Hollmig, Jim Pisoni, Kal Segrist, Carl Scheib, and Fox as being friendly. Maury Wills was the only African American on the rival Fort Worth Cats that year. Roberts would get together with Wills when the Missions played the Cats in Fort Worth, but all they could do for recreation was go to LaGrave Field early and play catch with each other.18

Although Roberts longed to return to his family in Panama, he stuck it out, due in part to the support he received from his manager, Don Heffner. For the season he hit .232 with 14 home runs and 84 RBIs in 153 games. He continued to show a great eye at the plate, walking 101 times, which resulted in an impressive .371 OBP.19

That winter, on February 25, 1956, Roberts married his junior high school sweetheart, Jeannette Eleanor Blake-Cummings. They had met in eighth grade in Gamboa, Panama, and would spend their lives together, raising four children: Charmaine (Robin), Dave, Jr., Sheilah Faye, and Lance.20

Roberts was back with San Antonio for 1956 where one of his teammates was a young third-baseman named Brooks Robinson. Roberts improved his batting average to .275 in 147 games but his home run total shrank to seven as he tried to hit more to the opposite field.

Through no fault of his own, but rather the overt bigotry of the Louisiana legislature, Roberts began 1957 back in Class A, with the Knoxville (Tennessee) Smokies of the SALLY League. Louisiana had passed a law prohibiting integrated athletic contests, which meant Roberts would not be able to play when San Antonio visited Shreveport. The Orioles response was to send him to Knoxville. Although Roberts feared the worst playing in another southern town, to his pleasant surprise he encountered no racial issues there before his recall to San Antonio about one-third of the way through the season.21

After a couple of months back with the Missions the parent Orioles sold Roberts to the Austin Senators, a Braves affiliate also in the Texas League. He finished the year there and returned in 1958, batting .294 with 20 home runs under the positive tutelage of manager Peanuts Lowery. He returned to his native Panama that winter and played for Cervaza Balboa in the Panama winter league, where he hit .299, the third highest average in the league.

Those performances earned Roberts, now 26, a promotion to Triple A with the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. After batting .252 in 1959 under manager Ben Geraghty,22 Roberts bounced around in 1960. The Braves started Roberts in Louisville in the spring, moved him to Triple-A Sacramento in the PCL by opening day, shifted him back to Austin in the Texas League in May, where the popular first baseman feasted on Double-A pitching until the Braves unloaded him in July to the Dallas-Ft. Worth Rangers, the Kansas City A’s affiliate in the Triple-A American Association.23

Roberts’ itinerant minor league journey continued in 1961, with stops in Jacksonville, where he predictably tore up Single-A pitching, and Triple-A Houston in the Cubs organization, where he struggled, hitting .208 in 41 games. At the end of the year, he decided to give up the dream and get a regular job in Los Angeles, where he and his wife had settled.

After working for a few months with a utility cart manufacturer, however, Roberts got an offer from the expansion Houston Colt .45s organization to start the 1962 season with their Oklahoma City club in the Triple-A American Association. As a result, he decided to give pro baseball another shot. He reported to spring training in Apache Junction, Arizona, and on the first day in camp was hit flush in the face with a fastball. It sent Roberts to the hospital for a week and kept him off the playing field for three weeks.

When Roberts was finally able to play again, he hit line drives all over the park and didn’t stop once the regular season began. Although a left-handed batter, he had particular success against southpaw pitchers. In one three-game series against Indianapolis, he faced three left-handers in consecutive games (including past and future big leaguers Herb Score and Gary Peters) and rang up nine hits in 12 at bats.24

Roberts was hitting .322 with 96 RBIs in 133 games when, around Labor Day, he was called up to the big leagues by the Colt .45s. At the time, Roberts was 29 years old, had played for 12 minor-league teams, and was in his eleventh minor-league season.

His first big league at-bat was in Houston on September 5, 1962 when he pinch-hit for pitcher Russ Kemmerer in the fourth inning of a game against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Against former Cy Young winner Vernon Law, Roberts hit a line drive that second baseman Bill Mazeroski leapt for and snagged.25

The following night manager Harry Craft sent Roberts to pinch-hit for J.C. Hartman in the bottom of the ninth with the Colt .45s down 3-2, two out, and runners on first and second. Facing ace Pirates reliever Roy Face, Roberts lined a shot to left-center for his first big league hit, driving in the tying and winning runs with a walk-off double.26

After a slow start, Roberts went 2-for-4 against the Milwaukee Braves on September 16 and slugged his first major league home run two days later with a drive deep to right field off New York Mets pitcher Larry Foss in the Polo Grounds. He finished the season with a .245 batting average with 10 RBIs in 16 games and 63 plate appearances. Roberts continued his habit of reaching base safely with a .349 OBP.27 He had also proven to be tough in the clutch, driving in 10 out of the 13 runners in scoring position during his at bats.28

Afterwards, Roberts played winter league ball in Venezuela for the LaGuaira Sharks where he hit .315 in 162 at bats.29

The Colt .45s were apparently not impressed, because after spring training in 1963 Roberts was sent back to Oklahoma City, which had joined the PCL. He spent the entire season there, hitting .270 with 16 home runs and 86 runs batted in. Although Roberts again played winter ball for LaGuaria in Venezuela, batting .310 in 49 games,30 for 1964 he was once more assigned to Oklahoma City. Now 31 years old, Roberts played with a vengeance, and after hitting .371 in 38 games, was recalled to the Colt .45s in late May.

Unfortunately, Roberts struggled at the plate initially after his recall and soon had his playing time reduced. To his surprise, on July 22 manager Harry Craft penciled the lefty Roberts into the line-up for a game in Los Angeles against Dodgers’ southpaw Sandy Koufax. On his second trip to the plate, Roberts lined a double to right-center field for one of the four hits Koufax allowed that evening.31 On August 12, Roberts hit his second and final major league home run, connecting with two outs in the top of the ninth to ruin a shutout bid by Tony Cloninger of the Milwaukee Braves.

Roberts was hitting only .184 in mid-September when General Manager Paul Richards sent Brock Davis and him home for the rest of the year so that the team could audition younger players. According to his memoir, Roberts was an angry man when the ’65 season started because of Houston’s treatment of him.32 He was back in Oklahoma City again and took his pique out on PCL pitchers, as he slugged 38 home runs, drove in 114 runs and batted .319 for the season. Those numbers did not warrant even a late season call-up from Houston, but Roberts was named the PCL’s Most Valuable Player and AP’s Minor League Player of the Year.33

Roberts was recruited that off-season to play in the Puerto Rico winter league for the Caguas Criollos where his teammates included Ferguson Jenkins and Grant Jackson and the manager was Frank Lucchesi. Roberts made the All-Star team and helped lead his team to the playoffs, where the Criollos lost in five games to the Ponce Lions.34

Roberts’ banner year did gain the attention of the Pittsburgh Pirates, who selected him in the minor league draft that winter. In spring training Pirates’ manager Harry Walker told Dave that he had made the team and was going to serve as the caddie for Donn Clendenon and Willie Stargell. Roberts’ playing time was indeed sparse and in June the Pirates sent him down to their Triple-A Columbus farm club in the International League.35

There, after a woeful 1-for-23 start for the Jets, Roberts caught fire, going 5-for-5 with three home runs on June 4 against Toledo. He continued his hot streak for the next ten days, smashing nine homers and driving in 22 runs in 12 games. At that point his manager Larry Shepard said, “He has about as much business being here as Willie Stargell.”36 Roberts finished the 1966 International League season with 26 home runs in 119 games to finish second in the league in circuit shots.

The Pirates, rather than call him back to the majors, sold him to the Baltimore Orioles who put him on their Triple-A Rochester roster heading into the 1967 season. Now 34 years old, Roberts was less than enthusiastic about another season in Triple A. While playing winter ball in Venezuela for the Lara Cardinals he was contacted by Sy Berger, the top executive for Topps, the baseball card company, about playing in Japan. Roberts was immediately interested and signed later in the winter to play for the Sankei Atoms, a team located in Tokyo that played in Japan’s Central League.37

After moving his wife and four children to Tokyo, Roberts had an immediate impact on the playing field, hitting 28 home runs and driving in 89, second most in the Central League in 1967.38 Roberts played winter ball in Venezuela after the season for the fourth time and returned to Japan in 1968 with an even better performance, smashing 40 home runs, second most in the league behind Sadaharu Oh, and driving in 94 runs (third most in the league) while batting .296. As a result, he was named to the Central League All-Star team and was the only gaijin on the league’s so-called “Best Nine.”39

Roberts had yet another banner year in 1969, finishing second in the Central League in batting (.318) to Oh, second in home runs (37) to Oh, and third in runs batted in (95) behind only Shigeo Nagashima and Oh. He was challenging for the Triple Crown before suffering a separated shoulder in an August game against the Tokyo Giants,40 but again made the Central League All-Star team and for the second year was the only gaijin on the League’s “Best Nine.”41

Roberts struggled with a bone spur in his foot during his fourth year in Japan, which caused his home run total to drop to 19. After a successful operation in Japan, he bounced back at age 38 to hit 33 home runs in 1971, third best in the league, along with 76 runs batted in, which was the fourth most. In all, Roberts played in Japan for seven years.42

Roberts had many memorable performances there, but perhaps his best day came against the Tokyo Giants when he hit three homers, three doubles, and two singles to drive in nine runs in a doubleheader.43 In 1971, the 38-year-old Roberts smashed ten home runs in ten days during one hot stretch.44

Roberts and his family embraced the Japanese culture and after a couple of years began living in Japan year around. When he first arrived, Roberts took it upon himself to learn one new Japanese word a day, and after a couple of years, he became fluent.45 He had always wanted to go to college and in the off seasons even took courses offered in English at Sophia University in Tokyo.

In 1973 Roberts was 40 years old, and while still productive, had become a part-time player. The Atoms were struggling on the field and in June purchased the contract of Joe Pepitone from the Atlanta Braves and released Roberts. The Atoms had an on-field celebration to honor Roberts on his last day with the team and offered him a coaching position, but the salary was too low and he declined.46 Pepitone, on the other hand, played only 14 games for the Atoms, batting just .163, and his poor attitude and histrionics made him the epitome of the “Ugly American” in Japan.47

Roberts signed for the rest of 1973 with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of Japan’s Pacific League but developed a bone spur in his other foot and decided to retire after the season. He had averaged 30 home runs per year during the six seasons he played full-time in Japan and was the first foreign player to hit 40 circuit clouts in a year. His 183 career home runs in Japan were the most ever by a foreign-born player and along the way he made three Central League All-Star teams.

In all the six-foot, 172-pound Roberts played professional baseball for 22 years, from 1952 through 1973, slamming a total of 433 home runs at all levels. In addition, Roberts played winter league baseball for at least nine years including five in Venezuela, two in Panama, one in Mexico, and one in Puerto Rico. He hit 43 more home runs in his winter seasons in Venezuela and Puerto Rico and undoubtedly a few more in his other winter league years.48

Roberts’ major league career was relatively brief and truncated, in part because he didn’t immediately produce when given his limited opportunities. One can only speculate as to why he wasn’t given more and longer opportunities or why he had to wait until he had played 11 minor league seasons and was 29 years old for his big-league debut. It is hard to deny, however, that his race was a factor at a time when most teams had an unspoken quota of two or three Black players per big league roster.

Roberts moved his family back to Southern California after retiring from baseball and tried to make ends meet by scouting for a year. He subsequently sold insurance for a few years until the economy took a nosedive in 1977 and 1978. Roberts then took what he thought would be a temporary job as a counselor at an LA area facility for emotionally challenged children. He rose to become the supervisor of the facility and stayed in the job for 12½ years before a back injury and subsequent surgery forced him to retire.49

Roberts and his wife eventually moved to the Dallas-Fort Worth area where he pursued his wood-crafting hobby, was active in his church, played golf with other retired ballplayers,50 and was a regular attendee at Ernie Banks-Bobby Bragan DFW SABR meetings. Although he had encountered rampant racism throughout his playing career, including his time in Japan, he displayed no bitterness and was unassuming and modest about his baseball career. As his health began to decline, Roberts maintained his habitual good humor and would, when asked how he was doing, say, “I’m fouling off the tough sliders and waiting for something down the middle.”51

Dave Roberts died on October 2, 2021 in Huntsville, Alabama, where one of his sons lives. He was 88 years old.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Tom Van Hyning for his ready assistance with information about Dave Roberts’ career in the winter leagues.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 The most famous “Dave Roberts” is the highly successful manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

2 Tony Salin, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes (Lincolnwood, IL: Masters Press, 1999): 49 (hereafter, “Salin”).

3 Dave Roberts and Tony Salin, My Baseball Odyssey (Sacramento: Embarcadero Press, 1999): 33, 113-114 (hereafter “Roberts & Salin”).

4 Roberts & Salin, 33.

5 Roberts & Salin, 2.

6 Roberts was a lefty all the way, however, throwing and batting left-handed.

7 After the Riverside-Ensenada experiment did not work, the team had become the Riverside-Portersville Comets until making Portersville its sole home on April 25. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed. (Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1997): 415.

8 Roberts & Salin, 6-7.

9 Roberts & Salin, 11.

10 Roberts & Salin, 18-19.

11 Roberts & Salin, 25; Interview with Dave Roberts by author, February 18, 2021.

12 Robin Roberts & C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996): 49-52.

13 Telephone interview with Dave Roberts by author, February 18, 2021.

14 The previous year Frank Calo, the Grand Forks manager, had shifted Roberts to first base, presumably since the team need a first baseman because Roberts was fleet afoot and covered a lot of ground in the outfield. Roberts & Salin, 28. He stole 28 bases with Aberdeen in 1954.

15 Roberts & Salin, 158.

16 Roberts & Salin, 37. Sadly, Fox was murdered that October in an altercation with belligerent patrons of a bar he co-owned in San Antonio. He was just 34 years old. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/howie-fox/.

17 Telephone interview with Dave Roberts by author, February 18, 2021.

18 Roberts & Salin, 38.

19 Roberts had taken free passes 99 times the previous year with Aberdeen.

20 Roberts & Salin, 161, 172.

21 Roberts & Salin, 41-43. Roberts batted .301 in 44 games in Knoxville.

22 Geraghty was a survivor of the Spokane Indians bus crash in 1946 in the Cascade Mountains which killed nine players and seriously injured several more. https://baseballhall.org/discover/baseball-history/in-1946-unfathomable-tragedy-struck-spokane-indians.

23 “Part of Answer in Roberts, Henry?,” Austin American-Statesman, May 10, 1960: 30; “Dave Roberts to Dallas-Ft. Worth,” Austin American-Statesman, July 8, 1960: 22.

24 Roberts & Salin, 61-63.

25 Roberts stayed in the game and in two successive at bats grounded out and struck out to go 0-3 in his debut.

26 According to his autobiography, Roberts didn’t realize that both runners had scored to end the game and stood at second base before teammate Jim Pendleton and others went out to tell him the game was over and congratulate him. Roberts & Salin, 64.

27 In his memoir, Roberts wrote that Johnny Temple and Norm Larker were particularly welcoming and supportive of him when he was called up to the Colt .45s. Roberts & Salin, 65-70.

28 Salin, 45.

29 https://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/.

30 https://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/.

31 The Dodgers won 1-0 as Koufax shutout the Colt .45s on four hits.

32 Roberts & Salin, 76.

33 “89ers PCL Champs,” Lawton Constitution, September 13, 1965:12; Roberts & Salin, 79-80. Roberts’ performance in Oklahoma City in the 1960s was not soon forgotten. In the early 2000’s, he was named the best player in Oklahoma City’s Triple-A history. Bob Hersom, “This Dave is one of city’s finest,” Daily Oklahoman, July 1, 2000: 155; “All-Time 89ers Team,” Daily Oklahoman, April 1, 2003: 20.

34 According to teammate Grant Jackson, Roberts was among the Caguas players who would mingle and play dominos in the town square with the locals. Telephone interview of Grant Jackson by Tom Van Hyning, June 1992.

35 Roberts was 2 for 16 in 14 games for the Pirates when he was returned to the minor leagues.

36 Tom Keys, “Roberts Leads Jets Over Wings,” Columbus (Ohio) Citizen-Journal, June 14, 1966.

37 Roberts & Salin, 87-88.

38 Roberts’ American teammate Lou Jackson led the club with 29 home runs.

39 Daniel E. Johnson, Japanese Baseball: A Statistical Handbook (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1999): 143.

40 Roberts & Salin, 185.

41 Johnson, 148.

42 In 1970 the team was purchased by the Yakulto Company and became the Yakult Atoms.

43 Roberts & Salin, 109.

44 He also that year surpassed Daryl Spencer’s career record for the most home-runs (145) by a foreign-born player. Roberts & Salin, 186.

45 The author’s first encounter with Roberts occurred around 2008 in a restaurant when the author overheard him speaking to someone on his cell phone in Japanese.

46 Roberts & Salin, 129.

47 Robert Whiting, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat: Baseball Samurai Style (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1977): 173-175.

48 https://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/; Francisco E. Toste, Jr., Paloviejo en los Deportes Beisbol, (Barcelo Marques & Co., 1966). The author was unable to locate Roberts’ complete statistics from his years playing in the Panamanian winter league or the Mexican Pacific League.

49 Roberts hurt his back breaking up a fight at the facility and after an operation, injured his back again. Roberts & Salin, 131-133; Salin, 49.

50 Roberts’ favorite golfing companion was former Brooklyn Dodger farmhand Mike Napoli who passed away in 2018.

51 Telephone conversation with Dave Roberts, February 18, 2021.

Full Name

David Leonard Roberts

Born

June 30, 1933 at Panama, Panama (Panama)

Died

October 2, 2021 at Huntsville, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.