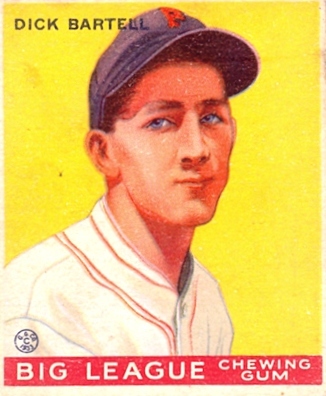

Dick Bartell

A highly competent fielder, a fine hitter, and an aggressive baserunner throughout the 1930s, Dick Bartell seems to fly under the radar when shortstops of his era are discussed. Thebaseballpage.com ranks Bartell 38th of the top 50 shortstops in baseball history. He had a career major-league batting average of .284 and played in three World Series. Yet, over the years he received only three votes from the baseball writers for the Hall of Fame, one each in 1951, 1958, and 1960. In the 21st century, mention of his name among baseball fans is likely to elicit a response of “who?”

A highly competent fielder, a fine hitter, and an aggressive baserunner throughout the 1930s, Dick Bartell seems to fly under the radar when shortstops of his era are discussed. Thebaseballpage.com ranks Bartell 38th of the top 50 shortstops in baseball history. He had a career major-league batting average of .284 and played in three World Series. Yet, over the years he received only three votes from the baseball writers for the Hall of Fame, one each in 1951, 1958, and 1960. In the 21st century, mention of his name among baseball fans is likely to elicit a response of “who?”

Richard William “Dick” Bartell was born in Chicago on November 22, 1907, to Harry and Emma (Greakel) Bartell. Harry Bartell worked variously as an accountant, real estate agent, and county supervisor. He was a semipro infielder whose claim to athletic fame occurred when he made an unassisted triple play. The Bartells moved to Alameda, California, when Dick was an infant.

Young Dick played sandlot ball in Alameda as soon as he was able to swing a bat. He was the varsity second baseman during his four years at Alameda High School. While in school, Dick played second base for the Yellow Checker Cab Company for $10 a game. After he graduated in 1926, the Pittsburgh Pirates (without signing him to avoid using an option) persuaded him to play semipro ball for a mining company in Butte, Montana. He signed with the Pirates after the season and joined the Pirates at spring training in Paso Robles, California, in 1927.

Bartell had impressed the Pirates as an agile shortstop with baseball smarts, a strong arm, and hitting potential. But that spring he faced stiff competition from such talented infielders as Pie Traynor, Glenn Wright, George Grantham, and young Joe Cronin. Bartell was farmed out to New Haven in the Eastern League. When an injured regular came back, New Haven sent him to Bridgeport in the same league. There, he hit .280 and the Pirates called him up at the end of the season. He made his major-league debut on October 2, the last game of the season, and drew a walk in his first at-bat as the pennant-winning Pirate regulars prepared for the World Series against the powerful Yankees.

Bartell impressed manager Donie Bush with his potential, hustle, and aggressiveness, and he remained with the Pirates through the 1928 season. He was the Pirates’ starting shortstop in the second half of the season, replacing the well-established regular Glenn Wright, who was sidelined with a serious arm injury. Dick proved he could handle the position as a regular, hitting .305 and fielding proficiently. Then he had a breakthrough season in 1929, hitting .302 with 184 hits and 40 doubles.

Bartell had serious difficulties with the Pirates front office, especially club owner Barney Dreyfuss. He wrote in Rowdy Richard, his reminiscence, “(Dreyfuss’) office was upstairs over the clubhouse. He’d send a message down for some player to come up to his office. It was not a pleasant experience. He was always looking for a chance to tell you why you weren’t as good as you thought you were. To keep the payroll down. We all dreaded those summonses.”

Bartell’s problems with Dreyfuss became even more serious before the 1930 season. He held out for a month before reporting. Then he had a fine year statistically, leading all National League shortstops in total chances per game and hitting .320 (in a year that produced an overall .303 National League batting average). But he feuded with the difficult Dreyfuss all season. It was no surprise when he was traded to the Phillies after the season.

The Phils had been the League doormat for years. They were a perennially underfinanced ballclub and stayed financially alive during the Depression years only by peddling their few stars for cash. They played in the Baker Bowl, the smallest park in the National League. It is remembered by baseball historians for its short right-field fence and the inflated offensive statistics that it produced. In August 1930, the Phils had two players, Lefty O’Doul and Chuck Klein, hitting over .400 (both ended the season in the .380s), but a group of ineffective pitchers and poor fielders. Bartell played his usual proficient game in 1931, hitting .289 and fielding well, one of the main reasons why the Phillies finished in sixth place after finishing last in 1930. The derisive term Philadelphia Ballplayer came into use as Phillies players compiled hefty hitting statistics, aided by Baker Bowl’s friendly confines, but were unable to duplicate their performances when they moved to other clubs.

Bartell did benefit from the trade in one way; he had good relations with Phillies president Gerry Nugent and Burt Shotton, who managed the Phillies in Bartell’s first three years with the club. They respected Dick for his aggressiveness and constructive impact upon his teammates. The Phils’ modest improvement continued over the next three seasons when the club avoided a last-place finish, a source of minor satisfaction to Bartell. When Nugent regretfully traded him to the New York Giants after the 1934 season, he was established as a top National League shortstop.

Bartell’s four seasons with the Phils were remembered for his competent play and his instilling badly needed life into the club, but mostly for his super-aggressive play on the bases. He was chosen to play in the first All-Star Game, in 1933, a reflection of his status as one of the best National League shortstops. But he was hated in Brooklyn. In the opening series that season he spiked Brooklyn first baseman Joe Judge as he ran out a groundball. Judge told Brooklyn writers that he had been spiked intentionally, a charge that Bartell denied. Then, later in the season, Dodgers pitchers knocked him down with four straight pitches and he retaliated by spiking Dodgers shortstop Lonny Frey. Both Judge and Frey were out for several games and Dick was hated even more by Brooklyn fans.

Bartell was a good fit for the Giants. Their first baseman-manager, Bill Terry, needed a replacement for the Giants’ longtime shortstop, Travis Jackson, and he was pleased to obtain Bartell. The very businesslike Terry also coveted Bartell to add spice to the longstanding Giants-Dodgers feud. New York writer Stanley Frank wrote in the New York Post: “Belligerent Bartell is probably the most hated Giant in the National League. Boys don’t like his flip tongue, his overweening arrogance, or the manner in which he throws his spikes into people’s faces while sliding into bases or charging across second on double plays. . . . Terry has had occasional tastes of Bartell’s hardbitten baseball, but now that the pepperpot is one of his own gang, he’s all in favor of it.”

Bartell had an uncertain start with Giants despite the feeling among Giants fans that, as Bartell put it, “I was supposed to be carrying the pennant in my back pocket.” He went into a slump early in the season and Bill Terry benched him for several games. And then, back in the lineup, Bartell made the mistake of laying down a sacrifice bunt without a signal from Terry, who scolded him after the game. Terry said, “You bunted to try to beat it out for a hit, but knowing that if you didn’t beat it out, it would be counted as a sacrifice, no time at bat for you. . . . Not without permission, I wouldn’t have bunted in that situation.” Coming from the freewheeling, self-concerned Phillies to the disciplined Giants, Bartell never tried that gambit again under Terry.

The Giants played well with the peppery Bartell breathing life into an aging infield, which also included Terry, second baseman Hughie Critz, and third baseman Travis Jackson. The Giants were in second place through Labor Day before falling into third place as the Cubs took the 1935 pennant with a 21-game winning streak. Bartell had an adequate season, although his batting average dipped to .262. He looked forward to the 1936 season as Terry traded with the Cardinals for second baseman Burgess Whitehead. Bartell felt that the agile Whitehead would be the perfect double-play partner he had lacked.

The Giants opened the season with Bartell in a typical role. In the first series of the year, Dodgers right-hander Van Lingle Mungo knocked him down with a pitch and Dick tried to retaliate by bunting toward first base hoping that Mungo would be within reach. The first baseman made the out unassisted, but Mungo came over and threw a hip into the much lighter Bartell. He appeared to fly through the air and came down on his back. He bounced up and both men swatted each other. During the brawl, Bartell accidentally hit peacemaker Bill Terry in the eye. Both Bartell and Mungo were ejected, but the old Giant-Dodger feud had been rekindled.

By midseason, the Giants were in fifth place and presumably were not contending for the pennant. But Bartell and Whitehead proved to be the best second base-shortstop combination the Giants had had in many years. The Giants bounced back and won the pennant. Carl Hubbell had a magnificent 26-6 pitching record with 16 consecutive wins as the regular season ended. Mel Ott led the offense with a fine offensive year. And the Bartell-Whitehead combination tightened the defense immeasurably and Bartell hit .298. In the World Series, the Giants did well to win two games against the overpowering Yankees, led by Lou Gehrig and rookie sensation Joe DiMaggio. Bartell personally had an excellent Series, leading the Giants with three doubles, a homer, and a .381 average.

Giants prospects were high as the club opened spring training in 1937. Terry and Travis Jackson had retired, but Hubbell and Hal Schumacher were in top form and promising left-hander Cliff Melton had been purchased from Baltimore. Bartell, Whitehead, Ott, left fielder Joe Moore, and catchers Gus Mancuso and Harry Danning were in their prime years. As they had for several years, the Giants barnstormed north with the Cleveland Indians in preparing to start the regular season. Teenaged flame-thrower Bob Feller, a sensation since joining the Indians during the 1936 season, was the big attraction. Bartell alone was unimpressed after Feller’s first outing, with the comment, “Heck, Van Mungo’s definitely quicker and we’ve got several other guys in our league who can throw as fast.” By the time the barnstorming trip ended, Feller had fanned Dick 13 times in 18 at-bats. Bartell had become a believer and, as a New York writer wrote, “Bartell had to go all the way from Vicksburg to Charlotte before he got so much as a loud foul against the kid.”

The Giants opened the 1937 season in Brooklyn in familiar fashion. Bartell led off in the first inning, taking the first pitch from Van Mungo for a strike. As he turned around to protest the call, he was hit squarely in the chest by an overripe tomato thrown by a fan in the stands behind first base. A few days later at the Polo Grounds, Bartell tagged Dodgers infielder Jimmy Bucher with more vigor than Bucher considered necessary and both men squared off. The players were separated and the game continued. But Bartell had managed again to keep alive his feud with the Brooklyn players and fans.

The Giants won their first three games in the season and they were tied with the Cubs for the league lead at midseason. These were the happiest days of Bartell’s time with the Giants. He led the Giants’ offense as Mel Ott battled a lengthy early-season hitting slump. The Bartell-Whitehead duo was at its best, and Bartell was rewarded with his second selection to the All-Star Game. Dick and his fully uniformed young son, Skip, were playful figures on the field before Polo Grounds games. On June 30, Bartell was given a “day,” and was presented with a silver statuette and other gifts.

Bartell proved that he had not lost his knack for becoming involved in fistfights on the field. This time his opponent was Cubs shortstop Billy Jurges. In the first game of a doubleheader in Chicago, Jurges tagged Bartell out roughly during a rundown play. In the second game, Bartell responded with an equally rough tag on Jurges as he slid into second base. Both men came up trading punches, and both were ejected from the game.

After the All-Star Game, the Giants slumped badly, and they were seven games off the pace by early August. Terry shook up the lineup to stimulate the lagging offense. His most significant move was to bench weak-hitting third baseman Lou Chiozza and replace him with Mel Ott, the best right fielder in the league. The Giants responded with an excellent homestand and they retained the resulting league lead for the remainder of the season. As in 1936, Hubbell and Ott led the Giants to the pennant. Hubbell led the league again in wins with a 22-8 record and Ott’s 31 homers tied for the league lead. And Bartell, who was selected to his second All-Star Game and again teamed beautifully with Burgess Whitehead, had a fine year, hitting .306.

The Giants faced the still-powerful Yankees in a virtual replay of the previous World Series. This time they were limited to only one victory, pitched by Hubbell. Bartell had a mediocre Series, hitting .238 and committing three of the nine Giants errors. Nevertheless, overall Bartell had an excellent season, and, still only 30 years old, he looked forward to several more good years with the Giants.

Giants prospects were high when the club began 1938 spring training in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Bartell had one major concern: The very competent Burgess Whitehead had an appendectomy in the spring and the physical and mental after-effects kept him out for the entire season. But regardless, the Giants had their best start in years. Favored to win again, they started off by winning 18 of their first 21 games to take a five-game lead over the second-place Chicago Cubs. Even without Whitehead and with several injuries, the Giants remained in first place through the midseason break.

The Giants slipped badly after the All-Star Game, and their play deteriorated at several positions. Most crippling, both Hubbell and Schumacher developed bone chips in their pitching arms and were lost for the season. Considering their injuries, the Giants did well to finish in third place. But Bartell had a mediocre season; he hit hitting .262, and his fielding slipped with the absence of Whitehead.

Changes on the Giants were inevitable as the season ended. The most important change involved Bartell. He, catcher Gus Mancuso and outfielder Hank Leiber were traded to the Cubs for their opposite numbers: shortstop Billy Jurges, catcher Ken O’Dea, and outfielder Frank Demaree. Bartell wrote in Rowdy Richard, “I was shocked. … I’d had an off year, but I was only 31. . . . Maybe the fact that … I was traded for Billy Jurges rankled me. I outhit him and was his equal in the field.” Bartell also wrote that Bill Terry later admitted he was sorry that he had traded Bartell for Jurges.

Hampered by back and leg problems, Bartell had a poor year with the Cubs in 1939, hitting a mere .238 and playing in only 105 games. He described the year as his career worst and he was glad to be traded to the Tigers after the season for another veteran shortstop, Billy Rogell. Bartell was especially gratified at the opportunity to team up with the Tigers’ Charley Gehringer, in Bartell’s view, the best second baseman ever.

Bartell’s statistics for 1940 are unimposing—a .233 batting average and a mediocre fielding average. But they do not indicate that Bartell once again was the spark plug he had been in his prime with the Giants. Tigers manager Del Baker encouraged Bartell to play his natural role as a catalyst and Dick complied. The 1940 Tigers — Hank Greenberg, Gehringer, et al. — were a relatively undemonstrative group and they needed a firebrand like Bartell to provide the liveliness they badly needed.

In a tight race, the Tigers caught up with the Cleveland Indians in early September and traded leads with them before pulling ahead to stay by winning two games of three as the season ended. Bartell figured importantly as the Tigers lost the seventh game of the World Series to the Reds. Dick was the goat in the last game when he failed to cut down a Reds run. As Charley Gehringer recalled the controversial play:

“We were leading 1-0 late in the game when (Reds first baseman) Frank McCormick led off with a double. The next guy up (Jimmy Ripple) hit a ball over Bruce Campbell’s head in right field. Campbell picked it up right away and threw it in to Bartell. Bartell thought, ‘Gee, with that double McCormick must’ve scored,’ but McCormick had waited to see whether it was going to be caught. So McCormick, who was no speed demon, was just rounding third when Bartell got the ball. I kept yelling, ‘Home, home, home.’ Gee whiz, with Bartell’s arm, he’s a dead pigeon. But he never did throw the ball. Even after he looked and still had a chance, he didn’t throw. And to this day, I don’t know why.” In his Rowdy Richard, Bartell wrote that he assumed McCormick had scored and added that because of the deafening crowd noise, he was unable to hear his teammates’ shouts for him to throw home.

In spring training in 1941 Bartell knew that his time with the Tigers was essentially over. He played in only five games before the club released him in early May. Shortly after, the Giants picked him up and he became Bill Terry’s third baseman with Billy Jurges, his old basepaths foe, the regular shortstop. Bartell hit a creditable .303 and played third base adequately. He began spring training with the Giants in 1942 full of pep and enthusiasm under Mel Ott, who had succeeded Bill Terry. Two of Dick’s erstwhile enemies, Van Lingle Mungo and Jurges, were now his teammates and several of his old Giants teammates who had been traded away rejoined him on the Giants. But Bartell played in only 90 games while hitting .244 and shifting between and third base and shortstop. As the impact of World War II on baseball deepened in 1943, Bartell performed similarly while raising his batting average to .270. He picked up his last major-league hit on September 7, then his season ended when the Dodgers’ wild-throwing rookie Rex Barney broke his wrist with an inside pitch.

Bartell, 36 years old, was drafted into the Army after the 1943 season. He spent the next two seasons coaching an Army baseball team. After his discharge, he returned to the Giants in 1946 as a third-base coach and part-time player. He played in only five games and his playing career was over.

With the Giants finishing in last place in ’46, there were rumors that manager Ott would be replaced and Bartell was included among the rumored possible applicants. But Ott was retained and Bartell left the Giants with hard feelings toward the Giants’ front office.

Bartell was hired to manage Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League in 1947. He lasted only the one year as the independent club was sold after the PCL season. Bartell hooked on in 1948 as manager of the New York Yankees’ American Association team in Kansas City. The Yankees cut loose their ties with Kansas City after the season and in 1949 Bartell returned to the majors as the third-base coach for the Detroit Tigers, with whom he remained through the 1952 season. He was inactive the following year but he was the third-base coach of the Cincinnati Reds in 1954-55. In 1956, in his last job in Organized Baseball, he managed the Montgomery, Alabama, club in the South Atlantic League.

Bartell’s 18-season career statistics include a .284 batting average, 2,165 hits, and a .952 fielding average. They do not adequate reflect his value as a dependable shortstop and his spirited, if occasionally unnecessarily combative, play. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract summed up Bartell: “Bartell didn’t drink a lot; he didn’t carouse a lot. But he had a big mouth, and he took pride in not backing away from people. Although he was an outstanding player, he bounced from the Pirates to the Phillies to the Giants to the Cubs to the Tigers and back to the Giants. The second half of his career he was a player … who was routinely booed in almost every city.”

Bartell married Olive Loretta Jensen on October 24, 1928, and the couple had two children. Olive died in 1977. Bartell worked in a variety of jobs in the Alameda area for several years after he left baseball. He suffered from Alzheimer’s disease over his last few years before his death at 87 on August 4, 1995, in Alameda. He was survived by his second wife, Anise Walton.

Sources

Books:

Dick Bartell and Norman Macht. Rowdy Richard. North Atlantic Books, 1987

Bill James. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. The Free Press, 2001

Fred Stein. Mel Ott–The Little Giant of Baseball. McFarland & Company Publishers, 1999

Fred Stein. Under Coogan’s Bluff. Chapter and Cask, 1979

Total Baseball Seventh Edition, Total Sports Publishing, 2001

Peter Williams. When the Giants Were Giants. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994

Full Name

Richard William Bartell

Born

November 22, 1907 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

August 4, 1995 at Alameda, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.