Dick Padden

At the turn of the 20th century, Dick Padden distinguished himself as one of the smartest men in baseball. Nicknamed “Brains,” the savvy second baseman found ways to take advantage of game situations. “Padden has the brains and also the talent,” declared sportswriter Jack Tanner in 1904.1 A “born leader” he was called.2

At the turn of the 20th century, Dick Padden distinguished himself as one of the smartest men in baseball. Nicknamed “Brains,” the savvy second baseman found ways to take advantage of game situations. “Padden has the brains and also the talent,” declared sportswriter Jack Tanner in 1904.1 A “born leader” he was called.2

Richard Joseph Padden was born on September 17, 1870, in Wheeling, West Virginia. He grew up in, and was a lifelong resident of, Martins Ferry, Ohio, across the Ohio River from Wheeling. His parents were Irish immigrants, Michael and Mary Ellen (née Gainerd) Padden, and he had an older brother Thomas. Mary Ellen died when Richard was three years old. Michael worked in a glass factory in 1880, according to the US census; the region was known for glass production.

Richard learned the trade of glass working3 and played for local semipro teams. On June 23, 1887, at age 16, he pitched for the Martins Ferry Red Stockings in a victory at Mount Pleasant, Ohio.4 On May 11, 1889, he struck out 12 in the Red Stockings’ triumph at Mingo, Ohio.5 And on June 28, 1890, he slugged three home runs and pitched a three-hitter for Toronto, Ohio, in a 17-0 rout of a club from Beaver, Pennsylvania.6

Padden threw right-handed. Sources disagree on whether he was a left- or right-handed batter; perhaps he was a switch-hitter.7 At 5-foot-10 and between 170 and 180 pounds,8 he was considered “big” in that era.9 After arm trouble forced him to give up pitching, he became a middle infielder.10

In 1894 Padden played in a pair of exhibition games against National League opponents. In the first contest, on October 3, he played second base for Martins Ferry against Connie Mack’s Pittsburgh Pirates and got one hit off Ad Gumbert.11 Three days later, he played shortstop for Wheeling and went hitless facing Cy Young of the Cleveland Spiders.12 In these two games, he excelled in the field, handling 15 chances without error.

After eight seasons of semipro ball, Padden joined the professional ranks in 1895 as the second baseman of the Roanoke Magicians of the Class B Virginia State League. He became manager of the team in June.13 In 122 games, he batted .316 and led the team in runs (104), home runs (11), and stolen bases (33). He was “phenomenal” in the field and “covered an immense amount of territory.”14 In the offseason he was acquired by the Pirates.

Padden began the 1896 season with Toronto, Ontario, of the Class A Eastern League, on loan from the Pirates.15 He played second base for Toronto and batted .281 in 60 games.16 He debuted with the Pirates on July 15 and went hitless facing Boston ace Kid Nichols.17 In his third game, on July 17, he stroked his first major-league hit, a triple, off Philadelphia’s Jack Taylor.18 His first major-league home run came on August 20 off Brooklyn’s Brickyard Kennedy. In 61 games for the Pirates, Padden hit .242, well below the league average of .290, but he impressed with his fielding at second base. “He goes after anything and everything, and is not afraid of errors,” said the Baltimore Sun.19

The next year, Padden played a full season with the Pirates and batted .282, close to the .292 league average. At Baltimore on June 18, 1897, he hit a double and home run and fielded 13 chances without error at second base.20 In the top of the 14th inning at St. Louis on August 6, he made “one of the most difficult catches that was ever seen on a ball field,” said the Pittsburgh Post. Tuck Turner lifted a fly ball that center fielder Jesse Tannehill lost in the sun. “Padden made a dash for center field and caught the ball on a dead run.”21 And in the bottom of the inning, he singled and scored the winning run.

In the second inning against Cincinnati on April 30, 1898, Padden was called out on a close play at second base. He argued with umpire George Wood and was ejected from the game.22 Pirates manager Bill Watkins agreed that Wood got the call wrong but nonetheless fined Padden $25 (about $900 in 2023 dollars) for getting ejected and thereby weakening the team.23 On the next pay day, May 16, Padden discovered that the fine had been deducted from his pay. He was furious and left the team in protest. “Padden is one of the best second basemen in the league,” said Watkins, “but as valuable as he is to the club, he must obey orders.”24 His teammates offered to pay his fine. He rejoined the team on June 12; it was not reported how the matter was resolved financially.25

On June 14, Padden’s two-run double in the ninth inning gave the Pirates a 3-1 victory over Cleveland.26 In the 10th inning on June 23, the New York Giants’ Jock Menefee “sent the ball into the air and it threatened to fall safely in the outfield between [center fielder Tom] O’Brien and [right fielder Patsy] Donovan. Like a streak of lightning Padden rushed to the scene and made one of the grandest catches of the year.”27

With a triple and home run, Padden drove in four runs in the Pirates’ 8-5 loss to Brooklyn on June 30.28 He went 5-for-6 at the plate, and handled 10 chances without error, in a 15-0 thrashing of Brooklyn on September 20.29

Padden hit .257 in 1898 (the league average was .271), and his fielding percentage was .947. Meanwhile, Henry Reitz batted .303 for the Washington Senators and led major-league second basemen with a .959 rate. In the offseason, the Senators traded Reitz to the Pirates for Padden and two minor-leaguers, Jimmy Slagle and Jack O’Brien. The trade turned out poorly for the Pirates. Reitz played in only 35 more games in the majors, whereas Padden, Slagle, and O’Brien played in a combined 2,177 games.30

Padden played second base and shortstop for the 1899 Washington Senators and served as the team captain.31 His work at shortstop was praised by Sporting Life: “As a shortfielder Dick Padden covers as much ground and plays as steady as at his old position on the second sack.”32 He did not have a strong throwing arm, but he made up for it by “his quickness in despatching the sphere.”33 In Cleveland on May 22, he was credited with nine assists at shortstop,34 but he had an off day against Cincinnati on July 11: He was charged with four errors, including three in one inning.35

Padden batted .277 for the Senators (the league average was .282). He struck out only 13 times in 451 at-bats, an impressive ratio of 1 in 35 at-bats. The major-league average was 1 in 16 that year (it was 1 in 4 in 2023). Padden was adept at getting hit by a pitch; he was hit 17 times in 1899. He “[gets] away with his old trick of putting his shoulder in front of a pitched ball,” noted the Pittsburgh Press.36

The Senators finished in 11th place in the 12-team National League and were one of four teams that were disbanded after the season. With the downsizing of the sole major league, Padden found himself back in the minors in 1900. He joined Charles Comiskey’s Chicago White Stockings of the American League, the year before it became a major league.

Padden hit .284 for the 1900 White Stockings and led the team with 36 stolen bases. He was “the best second baseman and the most successful field captain” in the league, said Sporting Life.37 The White Stockings won the pennant, and he was honored with a “Padden Day” celebration in Chicago on September 15.38

Comiskey’s team became the major-league White Sox in 1901, but Padden chose instead to join the St. Louis Cardinals of the National League. The 1901 Cardinals featured two future Hall of Famers, shortstop Bobby Wallace and outfielder Jesse Burkett. Padden fit in at second base and worked well in tandem with Wallace. Burkett marveled at Padden’s ability to play the hitters: “Old Dick seems to guess just where they are going to hit them. He is always there, anyway.”39

Padden stole 26 bases that year, but none was more exciting than his clean steal of home in the fifth inning in St. Louis on June 5, 1901. Christy Mathewson was pitching for the Giants, and he and catcher Aleck Smith were caught off guard by Padden’s daring. The theft brought 6,000 fans to their feet, and their cheering continued for a full three minutes. The Cardinals won the contest, 4-3.40

A week later, Padden wowed St. Louis fans in a 6-0 victory over the Philadelphia Phillies. Facing pitcher Al Orth in the first inning, he tripled with the bases loaded. In the eighth inning, while on first base, he took off for second base as catcher Ed McFarland tossed the ball back to Orth. The entire infield was caught by surprise, and he stole the bag without a throw. “It was a steal made purely on nerve and the faculty to grasp a situation and take advantage of it on the instant,” said the St. Louis Republic.41 But he wasn’t done. The Phillies batted in the ninth inning, and with a man on first, Jimmy Slagle lined a ball that bounced high off the bag at second base. Padden made a leaping catch, and before his feet touched the ground, tossed to Wallace for the force out at second base.

Padden batted .256 in 1901 (the league average was .267), and he ranked second among NL second basemen in fielding percentage. His manager, Patsy Donovan, said years later that Padden was “one of the smartest ballplayers I ever knew.”42

Padden and six teammates, including Burkett and Wallace,43 left the Cardinals to earn more money in the American League as a member of the 1902 St. Louis Browns. And Padden was chosen to captain the team. At the plate, he got off to a slow start, batting .155 through games of May 21, 1902. After May 21, he hit .287. He led major-league second basemen that year with a .967 fielding percentage. Stocked with former Cardinals, the Browns emerged as a pennant contender and finished in second place, five games behind the Philadelphia Athletics.

Padden was effective on the coaching lines, and he rattled opposing pitchers in a shrill voice.44 On August 9, 1902, he harassed Washington’s rookie catcher, Lew Drill. While on first base, Padden took off for second base while Drill held the ball. “Drill was sleeping and Padden’s yell brought him to life with a wild throw to center field.”45 Why yell and call attention to himself? To elicit a hurried throw, which if gone astray, might give him a chance to take third base.46

Whether for himself or a teammate, Padden found ways to take an extra base. On August 11, he outsmarted Washington first baseman Ed Delahanty. With Barry McCormick on first base, Padden laid down a sacrifice that was fielded by Delahanty. Padden abruptly stopped running and reversed back toward home plate as Delahanty chased him, giving McCormick time to reach third base.47 His sacrifice bunt thereby advanced the runner two bases. Browns owner Robert Hedges called Padden “the brainiest second baseman in the country.”48

Padden’s 1903 season was cut short by an injury to his right thumb. He sustained the injury in April and tried to play through it, appearing in 29 games. But his performance suffered, and in July he underwent season-ending surgery.49

In 1904 Padden returned to his role as second baseman and captain of the Browns. He batted .238 (the league average was .244) and led the AL with 18 times hit by a pitch. It was a disappointing season for the team, which finished in sixth place for the second year in a row.

A highlight of the 1904 season was a triple steal on September 26 against Washington. In the fifth inning, Padden was on third base, Joe Sugden on second, and Burkett on first. Pitcher Casey Patten was not paying attention to Padden, who made a mad dash for home plate. He slid in safely while Sugden and Burkett each moved up a base.50

Padden, at age 34, played in his final major-league game on May 4, 1905. He was released by the Browns two weeks later. There were two reasons given: He was in “poor health,”51 and the Browns saw 28-year-old Ike Rockenfield as their second baseman of the future.52 Padden scouted for the Browns near the end of the 1905 season. The next year, he was playing manager of the St. Paul Saints of the Class A American Association. He returned to the Saints in 1907 as solely a player and retired midseason after suffering an ankle injury.53

Padden scouted for the Browns in 1909 and Senators in 1910. He spoke humorously of the challenge of finding undiscovered talent: “Anything that looks like a ballplayer is optioned to death. I will have to begin with 2-year-old kids, or maybe yearlings, and take a chance, from the width of a baby’s shoulders, the color of his eyes and the tentacular appearance of his hands, that he will be a great ballplayer.” Regarding the high salaries given to ballplayers, he lamented that he was not born 15 years later; he quipped, “I can never forgive my parents for my premature debut upon the diamond.”54

After retiring from baseball, Padden resided in Martins Ferry and operated a billiard hall and bowling alley. In November 1915, at the age of 45, he married Mary Elizabeth Desch. She was a local lady of German ancestry, the 25-year-old daughter of a saloonkeeper.

On October 29, 1922, while playing pinochle at an Elks club, the 52-year-old Padden suffered a stroke. He died two days later in Martins Ferry – kidney failure and diabetes were blamed – and was interred at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Martins Ferry. He left behind a pregnant wife and four children: Thomas, Anna Marie, Richard, and Robert. In June 1923, Mary gave birth to twins, Lois and John.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by James Forr,

Sources

Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and Retrosheet.org, accessed March 2024.

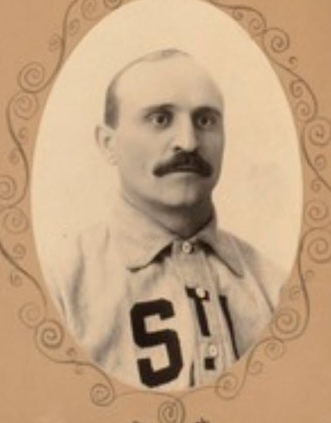

Photo credit: Carl J. Horner photograph of Dick Padden as a member of the 1902 St. Louis Browns, from the Boston Public Library.

Notes

1 Jack Tanner, “Dr. White’s Bat Wins His Own Game,” Chicago Inter Ocean, May 6, 1904: 4.

2 William A. Phelon, Jr., “Chicago Gleanings,” Sporting Life, December 22, 1900: 8.

3 “‘Dick’ Padden Is Dead,” The American Flint, vol. XIV, no. 2, December 1922: 13.

4 “Notes,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, July 24, 1887: 1.

5 “Martin’s Ferry Wins,” Wheeling Register, May 12, 1889: 1.

6 “Diamond Dust,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Intelligencer, June 30, 1890: 1.

7 Padden’s “player contract card” from the archives of The Sporting News indicates that he was a left-handed batter, but Baseball-Reference.com, accessed March 2024, indicates that he batted right-handed. Research by the author was unable to resolve the dispute.

8 “Base Ball over the River,” Wheeling Intelligencer, September 25, 1893: 1; “Dick Padden Playing Great Ball,” Wheeling Intelligencer, August 5, 1895: 3.

9 “At Roanoke City,” Lynchburg (Virginia) News, June 2, 1895: 3.

10 Sporting Life, February 25, 1899: 1.

11 “Smoky City Lads,” Wheeling Register, October 4, 1894: 6.

12 “Cleveland Won,” Wheeling Register, October 7, 1894: 4.

13 “At Roanoke City”; “Roanoke’s Revival,” Sporting Life, July 6, 1895: 16.

14 “He Has a Fine Team,” Roanoke (Virginia) Times, May 5, 1895: 2; “Honors Were Evenly Divided,” Roanoke Times, August 22, 1895: 1.

15 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, February 8, 1896: 5.

16 Sporting Life, July 18, 1896: 12; Sporting Life, November 28, 1896: 6. The 1896 Toronto team was temporarily transferred to Albany, New York, in July 1896; five of the 60 games played by Padden were played after this transfer.

17 Sporting Life, July 18, 1896: 3.

18 Sporting Life, July 25, 1896: 2.

19 “Diamond Flashes,” Baltimore Sun, August 31, 1896: 6.

20 Sporting Life, June 26, 1897: 2.

21 “They Perspire, but Are Happy,” Pittsburgh Post, August 7, 1897: 6.

22 “Bad Bill Eagan Plays Second Base,” Pittsburgh Post, May 1, 1898: 6.

23 “Notes of the Game,” Pittsburgh Post, May 1, 1898: 6.

24 “Padden Has Deserted,” Pittsburgh Press, May 17, 1898: 6.

25 “Pittsburg Points,” Sporting Life, June 18, 1898: 7.

26 “Dick’s Two-Bagger,” Pittsburgh Press, June 15, 1898: 5.

27 “Won in the Tenth,” Pittsburgh Press, June 24, 1898: 5.

28 Sporting Life, July 9, 1898: 2.

29 Sporting Life, October 1, 1898: 2.

30 Padden played in 551 games from 1899-1905; Slagle in 1,300 games from 1899-1908; and O’Brien in 326 games from 1899-1903.

31 “Baseball,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 17, 1901: III-6.

32 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, June 17, 1899: 7.

33 E.P. Mills, “Washington Whispers,” Sporting Life, May 27, 1899: 6.

34 Sporting Life, May 27, 1899: 3.

35 “The Reds Win the First,” Washington Times, July 12, 1899: 6.

36 “Clark’s Three-Bagger,” Pittsburgh Press, July 30, 1899: 12.

37 “Chicago Chips,” Sporting Life, August 4, 1900: 9.

38 “Celebrate with Defeat,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1900: 18.

39 A.R. Cratty, “Pittsburgh Points,” Sporting Life, April 27, 1901: 3.

40 “Harper a Wonder,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 6, 1901: 11.

41 “St. Louis Shuts Out Phillies—Padden Plays Great Ball,” St. Louis Republic, June 13, 1901: 5.

42 “Pat Donovan Digs into Baseball’s History Book,” Buffalo Commercial, August 18, 1917: 8.

43 The others who moved from the 1901 Cardinals to the 1902 Browns were Jack Harper, Emmet Heidrick, Jack Powell, and Willie Sudhoff.

44 Cratty, “Pittsburgh Points”; “St. Louis American League Baseball Team,” St. Louis Republic, April 10, 1902: 6.

45 “Browns Register Another Victory,” St. Louis Republic, August 10, 1902: III-2.

46 It was not reported whether Padden reached third base on this play.

47 “Senators Lose Third Straight to Browns,” St. Louis Republic, August 12, 1902: 6.

48 “Browns Will Keep Padden and Burkett,” St. Louis Republic, January 29, 1903: 11.

49 “Operation Performed on Padden’s Thumb,” St. Louis Republic, July 7, 1903: 7.

50 “Washington and Browns Battle to Eleven-Inning Tie, 2 to 2,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 27, 1904: 7.

51 “Richard Padden, Second Baseman, Late of the St. Louis (A.L.) Club,” Sporting Life, September 2, 1905: 1.

52 “Captain Padden Fired,” Meriden (Connecticut) Record, May 20, 1905: 1.

53 “American Association News,” Sporting Life, August 17, 1907: 13.

54 “All Sorts of Sports,” Houston Post, July 11, 1909: 17.

Full Name

Richard Joseph Padden

Born

September 17, 1870 at Wheeling, WV (USA)

Died

October 31, 1922 at Martins Ferry, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.