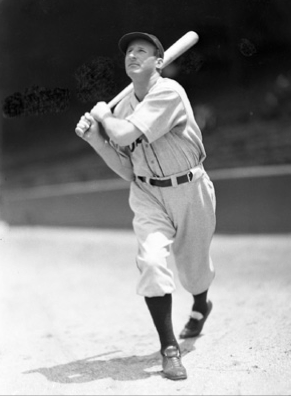

Goose Goslin

Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis called the 1935 World Series “the greatest ever.”1 Goose Goslin was the man of the hour after smacking a clutch ninth-inning single to cap the victory. Teammates mobbed the Goose; the incessant backslapping accompanied a bloody nose, mussed hair, and a torn uniform. The mood in the Chicago Cubs’ clubhouse was somewhat more subdued. Catcher Gabby Hartnett was asked what pitch Goslin hit. “That’s easy,” replied Hartnett: “He just hit a $50,000 pitch.”2 After a wait of 34 years, the Detroit Tigers savored the sweet taste of their first world championship. Navin Field fans chanted: “Yea Goose, Yea Goose, and Yea Goose!” A city still discouraged by the effects of the Great Depression celebrated all night long.3

Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis called the 1935 World Series “the greatest ever.”1 Goose Goslin was the man of the hour after smacking a clutch ninth-inning single to cap the victory. Teammates mobbed the Goose; the incessant backslapping accompanied a bloody nose, mussed hair, and a torn uniform. The mood in the Chicago Cubs’ clubhouse was somewhat more subdued. Catcher Gabby Hartnett was asked what pitch Goslin hit. “That’s easy,” replied Hartnett: “He just hit a $50,000 pitch.”2 After a wait of 34 years, the Detroit Tigers savored the sweet taste of their first world championship. Navin Field fans chanted: “Yea Goose, Yea Goose, and Yea Goose!” A city still discouraged by the effects of the Great Depression celebrated all night long.3

The festivities were far, in both time and place, from Salem, New Jersey, where Leon Allen Goslin was born on October 16, 1900. The family owned a working dairy farm, consisting of over 500 prime acres in nearby Fort Mott. Leon attended Sleepy Hollow rural school and was expected to do chores each day after dismissal. He loved baseball, and after-school games routinely kept him from his chores, angering his father. It was a time when young George Herman Ruth started making headlines and young Leon couldn’t help but notice and emulate the Babe on the field.

Parents James and Rachel Goslin were of English descent; their oldest child was Russell, born in 1895, followed by Mary in 1896, Leon in 1900, and James in 1912. Leon’s dad took ill, providing young Leon the responsibility of milking 25 cows each morning and evening. The strenuous farm work helped Leon grow to a solid 5-feet-11½-inches tall and 185 pounds.

Leon took a part-time job with DuPont, repairing elevators, on the condition that he play for the company team, and he eventually became the star right-handed pitcher. Bill McGowan was umpiring in a local factory league, and was impressed by young Leon’s raw ability the first time he saw him pitch. McGowan wired Zinn Beck, manager of Columbia in the Sally League, about the “can’t-miss” prospect. McGowan’s recommendation led to a signed contract. Goslin and McGowan became fast friends, with the umpire tutoring his young protégé in regard to proper dress and conduct during the train trip to South Carolina. Goslin later returned the favor by recommending McGowan for a promotion to the major leagues.

He was signed as a pitcher (winning six and losing five in 18 games), but Goslin’s bat prompted a move to the outfield, where he hit a league-leading .390 for Columbia in 1921. Jack Dunn, owner of the International League Baltimore Orioles, was ready to sign him for $5,000. Washington owner Clark Griffith caught wind of the plan and, surmising that Dunn knew talent, Griffith tricked a golfing buddy into revealing the prospect’s name and location. Griffith rushed to South Carolina and hurriedly signed Goslin for $6,000. Griffith, known as the Old Fox, pocketed the paperwork, climbed into the stands, and saw his new charge get conked on the head by a fly ball.

Despite fielding mishaps, Goslin earned a call-up to the Senators in the waning days of 1921. His nickname, Goose, was credited to Denman Thompson of the Washington Star, who observed the unorthodox flapping arms and erratic path taken as the young outfielder tracked fly balls. Washington skipper Clyde Milan was irritated with Goslin’s inept glove work and habitual breaking of training rules. Milan believed the touted youngster was not a shoo-in for a regular outfield position. But Goose’s bat kept him in the lineup; he played in 101 games and hit .324 in 1922.

Donie Bush took over as manager in 1923 and Goslin hit .300 while leading the league with 18 triples. Clark Griffith astutely noted that “good defense was just as important” and that Goslin “was severely lacking in that department.” The Nats owner considered “poor fielding to be a liability not compensated by a proficient bat.” Griffith prophetically commented: “Good hitters who were suspect fielders wouldn’t do on a championship- bound team.”4

Early in 1924, the Senators were languishing in seventh place under new manager Bucky Harris, then pulled up to .500 in June and won ten in a row (including eight on the road) to move into first place. The lead seesawed until late August, when the Nats took three out of four from the Yankees to establish a 1½-game lead over the defending American League champions. The Senators prevailed, copping their first AL flag. Goose hit .344 with a league-leading 129 RBIs. The Nats took the World Series in seven games over the New York Giants; the decisive game was a 4-3 thriller lasting 12 innings. Wrote W.O. M’Geehan in the Washington Post: “For the country at large the eagle may remain the national bird, but for the National Capital the greatest bird that flies is the goose.”5

The Senators repeated in 1925 and battled the Pittsburgh Pirates in the fall classic. Washington was favored to win, but it wasn’t meant to be as the Pirates took the title in seven games. The 1926 season saw Washington drop to fourth, with Goose contributing 109 RBIs, 17 homers, and a .354 average. The 1927 Senators finished third; Goslin knocked in 120 runs and hit .334. He swung from his heels and his left-handed power was complemented by an exaggerated closed stance in which he turned almost 180 degrees completing his swing. His stroke was fun to watch, whether he homered or struck out.

Spring training 1928 took place at the fairgrounds in Tampa, Florida, a location providing ample diversion for the fun-loving Goslin. A high-school track team was working out and Goose delighted in challenging runners to impromptu races. He approached a group of teens practicing the shot-put, picked up a 16-pound weight and proceeded to toss it like a baseball – for the next 30 minutes. The next morning his right arm was so strained that he couldn’t comb his hair.

The arm was swollen and discolored as the season opened. Goslin was sent to Atlantic City for salt-water baths, followed by ice packing, massaging, rest, and even a cast (although x-rays showed no break). Another diagnosis revealed that his collarbone was out of placement, prompting a trip to a bone-setter in Michigan. To Griffith’s chagrin, nothing worked. Goose’s throwing arm remained a liability all season and it became a ritual for infielders to run deep into the outfield to retrieve his weak throws. Despite the arm woes, his average was as high as.432 in late June.

Goslin’s.379 average ultimately beat a .378 mark posted by the St. Louis Browns’ Heinie Manush. In The Glory of Their Times, Goslin provided author Lawrence Ritter insight into his quest for the title – right down to his last at-bat. Goose realized that if he got a hit, he won; if he was out, he lost. Confronted with this dilemma, Goslin thought seriously about sitting it out, but teammates insisted he’d hear accusations of “being yellow if you win the title on the bench.”6

Goslin decided to take his licks, and quickly looked at two strikes. He decided to try to get thrown out of the game. Umpire Bill Guthrie read through the ruse and told Goslin: “You’re not going to get thrown out of this ballgame no matter what you do.” The ump added that a walk was out of the question too. Back in the box, Goslin got what he termed a “lucky hit” and won the title fair and square.7

Goslin’s average shrank to .288 in 1929, with 18 homers. The incredible power generated by his muscular shoulders was illustrated by a home run that cleared the high right-field fence at Griffith Stadium. It traveled an additional 75 feet into the backyard of a home where it struck the unsuspecting homeowner, who was hanging laundry. The ball struck with such force that it dislocated the woman’s shoulder.

Shirley Povich of the Washington Post commented: “Even when Goslin wasn’t meeting the ball, he was an exciting hitter. He emulated the Ruthian custom of swinging himself off his feet and depositing himself in the dust when he whiffed. He was the least plate-shy guy who ever lived. Umpires used to threaten to banish him unless he stopped crowding the plate.”8 He also had remarkable hand-eye coordination: so good that he once beat the New Jersey skeet shooting champ by hitting 50 out of 50 clay pigeons during a match.

After a salary dispute, Goose was shuttled to the St. Louis Browns on June 13, 1930, for Heinie Manush and General Crowder. Both teams were in St. Louis when the news broke and traveled like wildfire. Goose was greeted with “go to your own clubhouse” when he sauntered in from his pregame constitutional. A bellman handed him a telegram advising him of the trade; he read the correspondence and said: “They weren’t kidding, were they?”9

The trade was considered one-sided by St. Louis fans: a strong-hitting outfielder and a starting pitcher were shuttled for the services of just a hard-hitting outfielder. The reported circumstances precipitating the trade offered a clue to the imbalance. Before making the deal Browns owner Phil Ball visited the team hotel, intending to speak with Manush. He called Heinie’s room on a house phone and the operator told him, “Mr. Manush was tired and didn’t want to be disturbed during breakfast.” Incensed, the short-tempered owner stormed out.

Still seething from the Manush incident, Ball attended the afternoon game with friends. Crowder was pitching and after a bad call by the plate umpire, dispelled his anger by hurling the ball into the stands behind first base. The ball hit a railing, just missing Ball and his entourage. Phil got up, left the stands, went directly his office, and called his old pal Clark Griffith. Ball asked if he’d make an offer for Manush and Crowder. The stunned Griffith fumbled to think of a suitable player and quickly offered Goslin. While Griffith paused to think of another player to sweeten the trade, Ball quickly replied – “deal.” And so it was completed – straight up, with no cash involved. Clark Griffith and Goose Goslin had enjoyed what was referred to as a “father/son relationship,” but now it was over.10

The move invigorated Goose, who was having a subpar year. His average climbed to .308 and his home-run total increased to 37 with the two teams; it was the highest seasonal total of his career. The next season he hit .328 with 24 homers.

Goslin made headlines in 1932 when he attempted to use a camouflaged bat sporting black and white zebra stripes that ran its entire length. It was designed by Browns secretary Willis Johnson to annoy opposing pitchers. When Goslin came up in the first inning of the April 12 contest against the White Sox at Comiskey Park, umpire Harry Geisel ruled the bat illegal. Switching to a conventional piece of lumber, Goose proceeded to go 3-for-4 on the day. All told, he produced 104 RBIs for the 1932 Browns.

The minute Goslin heard that Walter Johnson had been fired as the Nats manager, he knew he’d end up back in Washington. On December 14, 1932, he was traded back to the Senators with left-hander Walter Stewart and outfielder Fred Schulte. The Browns received outfielders Sam West and Carl Reynolds and pitcher Lloyd Brown. When he traveled to Washington to sign his 1933 contract, sportswriters immediately noticed how he had changed during his tenure in St. Louis. The years away from Washington matured him; he was no longer as loud or boisterous as previously remembered.

Goslin fancied himself a managerial candidate and reportedly thought he’d be in line for the Senators’ top job; however, Joe Cronin was appointed the new skipper. Washington won the 1933 pennant, but was defeated in the World Series by the New York Giants.

Goslin never agreed with Cronin’s management style and the differences resulted in a trade to Detroit after the season. Coming off a subpar 1933 season (.297, 64 RBIs) and thought to be washed up, he was swapped for outfielder John “Rocky” Stone. On the surface the edge in the trade appeared to go to the Senators; however, the Tigers specifically sought a more powerful left-handed bat to complement the right-handed power of young Hank Greenberg.

Mickey Cochrane became player-manager of the Tigers in 1934, and Goslin further helped the pennant-bound Tigers by recommending that Cochrane deal for General Crowder to strengthen the pitching staff. The addition of both Goslin and Crowder helped the Tigers secure the 1934 flag, their first pennant since 1909.

Teammate Elden Auker recalled Goose as one to keep the players loose by clowning around. “He was some character, a really great guy,” Auker recalled. “He was just happy-go-lucky, always laughing and joking and pulling pranks.”11 On April 28, 1934, Goslin set the unenviable record of hitting into four consecutive double plays as the Tigers beat Cleveland 4-1. He enjoyed a productive 30-game hit streak and compiled a .305 batting average with 13 home runs. The Tigers finished seven games ahead of the Yankees, with the G-Men (Greenberg, Gehringer, and Goslin) leading the way.

The World Series pitted the Tigers against the St. Louis Cardinals. The Gas House Gang defeated Detroit in seven games; Goose drove in the winning run in Game Two. Just before the start of the seventh game, he remarked, “Everybody seems to be mad at everybody else in this Series, with all hands sore at the umpiring, which has been terrible, so watch out for fireworks today.”12 His prediction came true in the sixth inning when Joe Medwick slid hard into Tigers third baseman Marv Owen, causing a near riot among Detroit fans. When Medwick took his position in left field for the bottom of the sixth, the fans showered the field with debris. Judge Landis, watching from his third-base box seat, summoned the involved parties and removed Medwick from the game. The Cardinals went on to post an 11-0 win to cap the World Series.

The day after the Series Goslin became responsible for the first fine Commissioner Landis levied against a major-league umpire. The brouhaha erupted in Game Five when Goose referred to Bill Klem as Catfish, a name the ump detested. Commissioner Landis later determined that Klem had used “over-ripe language” to lecture Goslin on proper field conduct, and fined the umpire $50.13 Klem never forgave Goslin, even years later when the Goose tried to apologize for the incident.

The 1935 Tigers repeated as American League champs. The team started slow, lagging in sixth place through May, when suddenly the defending champs got hot. Although Goslin hit only .292, he provided a spark in the World Series against the Chicago Cubs. The Goose brought a rabbit into the clubhouse as a good-luck charm, thinking it would work better than just a rabbit’s foot. Indeed it did, as the club prevailed in six games.

Elden Auker recalled Game Six and the decisive Series win: “I was sitting on the dugout steps at the start of our half of the ninth and Goose was sitting beside me. Goose hadn’t had a hit all day and was the fourth hitter due up that inning. He turned to me and said something I’ll never forget: ‘I’ve got a hunch I’m going to be up there with the winning run on base and we’re going to win the ballgame.’ ” Mickey Cochrane singled and moved to second on Charlie Gehringer’s groundout. Goslin came up to the plate, facing left-hander Larry French. Goose fouled away the first pitch, then lined the next offering to right-center, scoring Cochrane and giving the Tigers a 4-3 victory – and their first World Series title. Auker and Goslin embraced, with Goose shouting: “What’d I tell ya? What’d I tell ya?”14

None other than Goslin’s old pal Bill McGowan was the first-base umpire for the decisive Game Six. McGowan later wrote that when Goose came off the field after the top of the ninth, he passed the umpire and remarked: “Go in and get your shower – I’m gonna dust one.”15

In 1936 Goslin was still solid for the second-place Tigers, contributing a .315 average and a team-leading 24 home runs. One homer came on September 18, when Goose welcomed Bob Feller to the major leagues by becoming the first player to hit one out against the hard-throwing rookie.

Spring training 1937 in Lakeland, Florida, started off on a good note for Goslin. He took a side trip to Miami Beach, and columnist Leonard Lyons reported that “rolling the dice at a gambling club, (Goslin) won more in one week than he’ll receive from the Detroit Tigers for a full season’s play.”16 Goslin’s salary that season was $12,000,17 and it would be the last season he’d draw a salary from the Tigers. The Tigers finished second to the Yankees. After playing in 79 games and hitting .238, Goslin was released on October 3, the day the season ended. Owner Walter Briggs thanked Goose for his contribution to the team and acknowledged that he’d become one of the city’s most popular players. Briggs hinted at helping the veteran find a spot as a coach or manager.

Early in 1938, Goslin left New Jersey for sunny Florida, with golf clubs, sport clothes, and scissors, hoping to catch on with another club. The former farmboy had become quite the fashion plate and habitually dressed for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Golf was his second-favorite sport and the scissors were needed to clip coupons.18 Although one of the wealthiest players in the game, the thrifty Goslin was frugal and saved an extra few cents to keep expenses down as he looked for a job. During the heyday of his career, he earned a top salary of $16,000 and was estimated to have pocketed more than $35,000 alone from World Series money. These funds were carefully invested, enabling him to make his South Jersey farm a showplace.

Apparently Goslin was bitter after the Tigers prevented him from talking to Cleveland about a managerial spot. “I’m sore at the Detroit club,” he told columnist Shirley Povich. “You’d think after the time I spent in the league they’d give me a break if I could land a manager’s job. And then after the season closed, they let me go without any warning at all. That wouldn’t have been so bad, except that they gave me my release a day after I had buried my father. That seemed kind of harsh to me.”19

Just before the 1938 season began, Goslin unretired and signed with Washington – his third stint as a Senator, but the hits were few; he batted only.158 in 38 games before age and injury finally caught up with him. Hitting against Lefty Grove, Goose swung so hard that he wrenched his back and was unable to complete the plate appearance. It was the only time in his career that a pinch-hitter took his place. Goslin retired, having posted a career average of .316, with 2,735 hits, 500 doubles, 1,483 runs, 173 triples, and 248 home runs.

The next season Goslin became the player-manager of the Interstate League’s Trenton Senators. In 1940 he wed Marian Wallace, a Philadelphia social worker. Marian died in 1960; the couple had no children. By August 1941, in the midst of a 15-game losing streak, he abruptly quit as Trenton manager and retired from the game. In addition to devoting time to his farm and boat business, Goslin continued to golf, fish, and bet on horseraces.

The Veterans Committee elected Goslin to the Hall of Fame in 1968. At the induction ceremony, in a stirringly emotional speech, Goslin wept when he recounted: “I have been lucky.” His eyes became wet with tears, as he tried to continue – “I want to thank God, who gave me the health and strength to compete with these great players.” He then began to cry uncontrollably, until he felt the steady hand of Commissioner William Eckert on his shoulder. Heartfelt applause from the audience gave him the confidence to continue, “I will never forget this. I will take this to my grave.”20

Goslin died in Bridgeton, New Jersey, on May 15, 1971, at the age of 70. He had been in declining health since 1969 when he was hospitalized for burns that resulted when he fell asleep while smoking. He was survived by his two brothers and his sister. He was buried at the Baptist Cemetery, near Salem.

Goose Goslin never truly earned the respect due a player of his caliber. He was generally acknowledged as a “money player,” evidenced by his run of World Series appearances in 1924, 1925, 1933, 1934, and 1935. Goose referred to himself as a farmboy having fun playing the game he loved. His contemporaries felt he hadn’t taken the game seriously and never lived up to his full potential. Even on the day of his Hall of Fame induction, Goslin wasn’t shown the proper respect. On what should have been the greatest day of his life, he and his party were summarily ushered out of the hotel right after the ceremony, because the hotel needed their suite. Apparently Goose never responded to an inquiry from the hotel regarding the number of nights he and his party intended to stay.

An updated version of this biography is included in the book “Detroit the Unconquerable: The 1935 World Champion Tigers” (SABR, 2014), edited by Scott Ferkovich.

Sources

Auker, Elden, and Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006).

Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: HarperCollins, 2000).

Luke, Bob, Dean of Umpires: Bill McGowan (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005).

Ritter, Lawrence, The Glory of Their Times. (New York: William Morrow Co., 1992).

Thomas, Henry W., Walter Johnson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998).

Daly, Arthur, “Sports of the Times, Two For Cooperstown,” New York Times, February 2, 1968.

Ward, Arch, “And What if He Had Used It?” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 13, 1932.

“Goslin’s Home Run Ball Fells Woman,” Washington Post, August 29, 1929.

Notes

1 James P. Dawson, “Tiger Clubhouse Becomes a Bedlam,” New York Times, October 8, 1935.

2 Ibid.

3 Westbrook Pegler, “Fair Enough,” Washington Post, October 5, 1935.

4 Frank Young, “Poor Fielding Nullifies Good Battery,” Washington Post, December 2, 1923.

5 W.O. M’Geehan, “Goose Displacing Eagle’s Popularity,” Washington Post, October 8, 1924.

6 Lawrence Ritter, The Glory of Their Times.

7 Ibid.

8 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, February 16, 1954.

9 “Goslin Last to Hear He Has Been Traded,” Washington Post, June 15, 1930.

10 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis.

11 Elden Auker and Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms.

12 Ibid.

13 Associated Press, October 11, 1934; “Goose Goslin, Outfielder, Dead; Elected to Hall of Fame in 1968.” New York Times, May 16, 1971.

14 Auker.

15 Bill McGowan, “The Umpire Talks Back,” Liberty, September 11, 1937.

16 Leonard Lyons, “The Post’s New Yorker,” Washington Post, March 11, 1937.

17 Michael Haupert research of Hall of Famers’ contracts, via baseball-reference.com.

18 Shirley Povich, “You Needn’t Worry About the Goose,” Washington Post, March 9, 1938.

19 Ibid.

20 “Goose Goslin, Outfielder, Dead; Elected to Hall of Fame in 1968.” New York Times, May 16, 1971.

Full Name

Leon Allen Goslin

Born

October 16, 1900 at Salem, NJ (USA)

Died

May 15, 1971 at Bridgeton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.