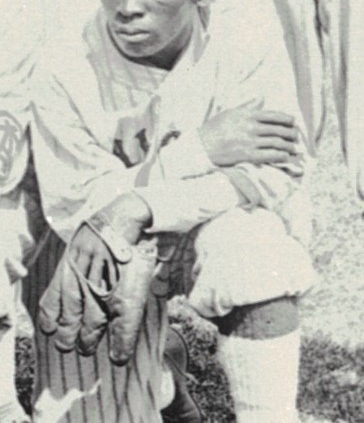

John Reese

As his nicknames, Speed Boy and Sparkplug,1 suggest, John Edward Reese was a fleet-footed outfielder who put together a 12-year career at the highest levels of professional baseball in the Negro Leagues. Although he spent most of his career as a reserve outfielder, he was talented enough to play in the outfield alongside some of the greatest players in history. When his playing days were largely over, he had a brief, but highly successful run as a manager, steering the St. Louis Stars to the last two pennants of the Negro National League in 1930 and 1931.

As his nicknames, Speed Boy and Sparkplug,1 suggest, John Edward Reese was a fleet-footed outfielder who put together a 12-year career at the highest levels of professional baseball in the Negro Leagues. Although he spent most of his career as a reserve outfielder, he was talented enough to play in the outfield alongside some of the greatest players in history. When his playing days were largely over, he had a brief, but highly successful run as a manager, steering the St. Louis Stars to the last two pennants of the Negro National League in 1930 and 1931.

Reese was born on April 19, 1895,2 in Pensacola, Florida. Little is known of his early life, but the 1910 US Census shows him still living in Pensacola with his mother, Carrie Reece, and stepfather, James Reece.3 James Reece was listed as a bay man in the ship-loading field. Although he adopted his stepfather’s surname, Reese himself spelled it “Reese.” On occasion, however, various sources, including box scores, continued to render his last name as “Reece.“

By 1915 Reese was a student at Morris Brown College in Atlanta. One of Georgia’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), Morris Brown was founded in 1881 under the auspices of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In the 1917-1918 Morris Brown catalog, a John E. Reese is listed as a junior in the Commercial Department.4 The aim of the department was “to give a theoretical and practical education to young men and women who are looking forward to business careers.”5 While at Morris Brown, Reese was a member of the school’s baseball team. A rare box score from 1915 shows “Reese” playing center field and scoring two runs in a 9-5 victory over crosstown rival Morehouse College.6 In the following year, Reese and two teammates were touted for fielding which “created a sensation,” in a losing effort to visiting Howard University.7

In early April 1917 the United States declared war on Germany. Reese was one of the millions of young American men who were required to register for the military draft in June 1917 as the nation prepared to enter the First World War. At that time, he put down Morris Brown as his residence. He gave his occupation as janitor, with B.J. Davis at the Odd Fellows Building in Atlanta as his employer. Benjamin J. Davis Sr., a prominent African American of Atlanta, was the founder and editor of the Atlanta Independent, a weekly newspaper that began publication in 1903. Reese also listed a mother and 3-year-old child as dependents. Since he indicated his marital status as single, it is unclear if the mother listed was his own mother, or the mother of his child (if he had fathered one).8

Reese was not called into military service, and in 1918 he made his way north to begin his career as a professional baseball player with the Hilldale Club of Darby, Pennsylvania. Located on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Darby had been home to a Black amateur team since 1910. Under the leadership of its primary owner and team president, Ed Bolden, Hilldale became a fully professional team in 1917.9 Reese joined four other recent Morris Brown College alumni on the team’s roster: Elias “Country” Brown, McKinley “Bunny” Downs, Daniel “Shang” Johnson, and Tom Williams. The 1918 team also included future Hall of Fame catcher Louis Santop; and a young Judy Johnson made a very brief appearance with the team that year before beginning his own Hall of Fame career in earnest several years later.

As an independent Black team with no league in which to compete, Hilldale scheduled games against other professional Black ballclubs, as well as White semipro, industrial, and military teams. A local newspaper declared that Hilldale “played the strongest teams obtainable.”10 Sunday games in Philadelphia were prohibited by the blue laws in force at the time, so many Hilldale players, including Reese, made the short trip to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where there were no restrictions on Sunday games, to play for the Bacharach Giants. Although Reese struggled at the plate during his first season as a professional, he regularly started in the outfield, primarily as the center fielder for both Hilldale and the Bacharach Giants.

At the end of Reese’s first season with Hilldale, a September game was scheduled against a barnstorming team advertised as the World Champion Boston Red Sox. The Red Sox had just defeated the Chicago Cubs in the 1918 World Series. While the “Red Sox” team that Hilldale faced did in fact have four members of the 1918 Red Sox, the rest of the team was composed of current or former players from other teams. Reese led off for the home team in the bottom of the first inning with a single off Bullet Joe Bush of the Red Sox and scored Hilldale’s first run. Hilldale was behind 4-3 going into the bottom of the ninth inning, but when Bush refused to accept a new ball in place of one that had been removed from play, the game was awarded to Hilldale by forfeit.11

Reese was one of seven players from the 1918 Hilldale squad who returned for the 1919 season. Taking over the starting spot in left field, he had a strong season at the plate. At the end of the season, Hilldale faced off against the Bacharach Giants in what the local press in a bit of hyperbole proclaimed was “for the colored baseball championship of America.”12 The game was played at Shibe Park, the first time Black baseball teams were permitted to play on the home field of the American League’s Philadelphia Athletics. Hilldale did not fare well against the Giants and Cannonball Dick Redding. Redding gave up only three singles in the game, one of them to Reese, on the way to a 10-0 shutout.13

Reese apparently made his offseason home in Pennsylvania: The 1920 Federal Census shows a John Reese living as a boarder in Philadelphia in early January of that year. The census taker recorded the respondent’s occupation as “Ball Player,” and his industry as “Team,” leaving little doubt that he was John Reese of the Hilldale Club.14 In any case, Reese would not be living in Philadelphia for much longer.

In February 1920 Black team owners at the behest of Rube Foster met in Kansas City, Missouri. The meeting resulted in the creation of the first organized league for Black teams. The new league was called the Negro National League. Many years later, in December 2020, the league was officially recognized by Major League Baseball as a major league.15 As the primary mover for the new league, Foster became its first president. A former outstanding pitcher himself, Foster owned and managed the Chicago American Giants, one of the most successful teams in Black baseball. Foster’s Giants had competed against Hilldale in previous seasons and, as he was always on the lookout to improve his team, Foster recruited Reese and pitcher Tom Williams away from Hilldale to join the Giants for the 1920 season in the new league.

In a preseason review, a reporter for the Chicago Defender wrote that “Reese, the new outfielder, comes here from the Hilldales of Philly. He has been facing all the high class twirling of the eastern hurlers, and if there are any thing to the signs, then he supplies that punch the fans so feared might be missing.”16 Reese was projected to be in the starting outfield alongside veterans Judy Gans and future Hall of Famer Cristóbal Torriente.17 Reese did indeed win a starting position in Chicago’s outfield, but partway through the season he was replaced in the starting lineup when the Giants acquired Floyd “Jelly” Gardner from the Dayton Marcos. Reese, however, remained a regular contributor down the stretch as the Giants won the pennant in the Negro National League’s inaugural season.

Reese began the 1921 season with Tenny Blount’s Detroit Stars. His new teammates included two future Hall of Famers, player-manager Pete Hill and pitcher Andy Cooper. Reese played left field and batted second for his new team as it got off to an excellent start. By the end of June, Detroit had raced to a league-leading record of 17-3.18 Reese was in the lineup for an early-season highlight when his teammate, veteran right-hander Big Bill Gatewood, tossed the Negro National League’s first no-hitter en route to his career-best season at age 39.19

By early July, however, Reese was back with the American Giants. He got some extra playing time at the end of that month when he replaced left fielder Jimmie Lyons in the starting lineup. Lyons had fallen 25 feet down a hotel elevator shaft when the Giants were on the road for a series against the Cincinnati Cuban Stars.20 Although Lyons quickly recovered from the fall to reclaim the starting job, Reese still ended up logging the fourth most games in Chicago’s outfield as the Giants won their second consecutive league title. He remained with the Giants throughout the 1922 season in his familiar reserve outfielder role behind the well-established starters Torriente, Lyons, and Gardner as Chicago captured its third straight league pennant.

After three championship years with the Giants, Reese opened the 1923 season with the Toledo Tigers. Toledo was one of the Negro National League’s two new teams, along with the Milwaukee Bears. The pair replaced the Cleveland Tate Stars and Pittsburgh Keystones, who had left the league after only one season. Reese started in the outfield for the Tigers, playing all three positions and leading the team in stolen bases and runs scored. Toledo was unable to finish out the league season, ending its only year of play in July. Reese and six of his Tigers teammates were quickly picked up by the St. Louis Stars. One of the former Tigers, veteran third baseman Candy Jim Taylor, took over as player-manager. Although the Stars finished the season with one of the worst records in the league, Reese again played all three outfield positions and batted .316 down the stretch for his new team. His combined statistics for the 1923 season with Toledo and St. Louis represented career highs for him in almost all offensive categories.

Reese’s first few seasons with St. Louis were among the best of his career. The Stars began to build a strong team that in a short time challenged the Chicago American Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs for league supremacy. When Reese arrived on the team in 1923, it already had a young pitcher who was soon converted into one of the greatest center fielders in Negro Leagues history, Cool Papa Bell. Nineteen-year-old shortstop Willie Wells joined the team in 1924 to embark upon his Hall of Fame career as St. Louis improved its record and returned to the top half of the league standings.

In 1925 the Negro National League instituted a split season with the league champion to be determined by a postseason playoff between the first- and second-half winners. By then, Reese had again become a reserve outfielder, although still a useful one. His performance in an early-season doubleheader led the St. Louis Argus to report that Reese “proved that he can still hit, and his throwing arm has returned to form. He played a great game getting two hits in the first game and connecting once in the second contest. So, this gives the Stars much needed reserve strength.”21 The Stars finished second in the first half of the season, then took first-place honors in the second half to set up the league’s first postseason playoff against the Kansas City Monarchs. Reese was used as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement in four games as the Stars lost a tightly contested series to the Monarchs, 4 games to 3.

For the 1926 season, the St. Louis lineup was bolstered by the addition of the third future Hall of Famer to its lineup, slugging first baseman Mule Suttles. Reese played only sparingly in 1926, but he took over as the team’s manager partway through the season.22 He then led the Stars to an impressive 40-17-2 record to end the season, but it was only good enough to finish behind the second-half winners, the Kansas City Monarchs.

Despite his successful stint as manager, Reese was not brought back to lead the team in 1927. The 1926 season also effectively marked the end of Reese’s career as a player. He apparently appeared in no games in 1927 or 1929, and in only one game in 1928. As a result, he was not a part of the Stars’ first league championship in 1928. They easily won the first half of the season before facing the second-half winners, the Chicago American Giants. In a hard-fought nine-game series, the Stars dethroned the two-time defending champions, in the process becoming the only team other than the Giants or the Kansas City Monarchs to win a Negro National League title.23

It later turned out that Reese’s career with St. Louis was not yet finished after all. Subsequent to a three-year absence, he returned as the team’s manager in 1930. Under Reese’s leadership the Stars won the season’s first half. Reese occasionally inserted himself into the lineup, mostly as a pinch-runner, but in a mid-July contest he played in right field and led off for St. Louis. He went 2-for-4, including a triple, and scored two runs in a win over the Louisville Black Caps.24 Ahead of an August series with the Nashville Elite Giants, Reese demonstrated his competitive leadership by commenting, “If we can ‘take’ the champions [i.e. the Monarchs] three straight … why can’t we sop up the tailenders.”25 The Detroit Stars, managed by Reese’s old Chicago American Giants teammate Bingo DeMoss, won the second half of the season. They faced off in another tight series, which St. Louis won 4 games to 3 by taking the final two games. Reese even got himself back on the playing field as a pinch-runner in the fourth game of the series.26 The Stars were honored with a parade in St. Louis followed by a banquet at a local YMCA, where Reese was presented with a “St. Louis Stars, World’s Champions, 1930” banner.27

Reese returned to manage the Stars for the 1931 season. In an early season matchup, the Stars faced the Indianapolis ABCs, a team managed by Reese’s former St. Louis teammate and manager, Candy Jim Taylor. In a lead-up to the contest, the Chicago Defender recognized Reese as “one of the most astute bosses in the game today,” adding, “It is a deep problem to determine what will be the outcome when he matches his wits with those of Jim Taylor, called the second Rube Foster by close followers of the game.”28 In August the St. Louis Globe-Democrat Sunday Magazine ran a feature profiling the Stars’ success. John “Sparkplug” Reese was described as a “baseball graduate from that most renowned of all Negro baseball clubs – Rube Foster’s American Giants of Chicago.” The story went on to say that Reese was “a wily field general whose rule of strategy may be confined to a single sentence … ‘Sock ‘em and keep ‘em socked.’”29

For the 1931 season, the depleted Negro National League was down to only six teams. Under Reese, the Stars easily won both halves of a shortened season and were declared the league’s uncontested champions. But the economic difficulties of the Great Depression brought the 12-year run of the league to a sad end after the 1931 season.30 The Stars did have a chance to cap off their final season at the beginning of October by winning both games they played against the Max Carey All-Stars, a barnstorming team of current and former major leaguers. Although the All-Stars included future Hall of Famers Bill Terry, Paul Waner, and Lloyd Waner, they did not have much luck against one of the Negro Leagues’ best teams. In the first game, the Stars’ Ted Trent struck out Paul Waner and Babe Herman twice, and Bill Terry four times.31 The All-Stars fared even worse in the second game, getting overwhelmed, 18-1.

Although Reese had demonstrated his leadership capabilities in two-plus seasons as the St. Louis manager, it appears that his career in baseball came to an end in 1931, along with the demise of the Negro National League. His post-baseball life is largely a mystery. He gave an Atlantic City address in 1937 when he applied for a Social Security account number.32 In 1944 he and Freddie Inez Thomas were married in West Palm Beach, Florida.33 The 1945 Florida State census shows he and his wife living in West Palm Beach,34 and West Palm Beach was apparently his home for the remainder of his life. He died on October 5, 1966, of undisclosed causes at the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., and his remains were to be returned to West Palm Beach for burial. In addition to his wife, he was survived by two daughters, Hortense Reese Green and Catherine Reese; a son, John Edward Reese Jr.; six grandchildren; and 12 great-grandchildren.35

Sources

Unless otherwise indicated, statistics and team records were obtained from the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database (seamheads.com), baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994), 657.

2 Reese’s World War I draft registration card, dated June 5, 1917, lists his birthdate as April 19, 1895, but his Social Security application dated September 1, 1937, lists a birthdate of April 15, 1897.

3 1910 United States Federal Census, accessed from Ancestry.com.

4 Morris Brown College Catalog, 1917-1918, 61, Atlanta University Center-Robert W. Woodruff Library, https://radar.auctr.edu/islandora/object/auc.007.catalog%3A1917.01.

5 Morris Brown College Catalog, 1917-1918, 50.

6 “Morris Brown Defeats Morehouse,” Savannah Tribune, April 3, 1915: 1, accessed from the America’s Historical Newspapers database.

7 “At Morris Brown,” New York Age, April 20, 1916: 2, accessed from the America’s Historical Newspapers database.

8 World War I draft registration card for John Edward Reese, Precinct 4C, Atlanta, Georgia, June 5, 1917, accessed from Ancestry.com.

9 For more information on the Hilldale Club see Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1994), and Courtney Michelle Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017).

10 “Hilldale Building Strong Team,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 20, 1919: 14, accessed from Newspapers.com.

11 For a detailed account of the game, see Bill Nowlin, “The One Time the ‘Boston Red Sox’ Played a Black Team,” Baseball Research Journal 50: 1 (Spring 2021): 80-84.

12 “Hilldale and Giants Battle for Title Today,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 1919: 13, accessed from Newspapers.com.

13 “Bacharach Giants Crush Hilldale,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1919: 14, accessed from Newspapers.com.

14 1920 United States Federal Census, accessed from Ancestry.com.

15 In addition to the Negro National League (1920-1931), the other six leagues recognized as major leagues were the Eastern Colored League (1923-1928), American Negro League (1929), East-West League (1932), Negro Southern League (1932), Negro National League (1933-1948), and Negro American League (1937-1948).

16 David Wyatt, “Nothing Lacking to Make Giants Great, ‘Rube’ Has Fine Team by All the Dope,” Chicago Defender, April 10, 1920: 11.

17 Wyatt.

18 Chicago Defender, July 2, 1921: 10.

19 See Donna L. Halper, “June 6, 1921: Bill Gatewood of Detroit Stars throws Negro National League’s first no-hitter,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-6-1921-bill-gatewood-of-detroit-stars-throws-negro-national-leagues-first-no-hitter/, accessed December 22, 2021.

20 “Jimmy Lyons Falls Down Elevator Shaft,” Chicago Defender, July 30, 1921: 11.

21 “St. Louis Stars Win Series from the Memphis Red Sox,” St. Louis Argus, May 15, 1925: 6, accessed from the Internet Archive (archive.org).

22 Branch Russell started the season as the team’s manager and was replaced by Dizzy Dismukes before Reese took over managing duties.

23 See Kevin Johnson, “St. Louis’s Forgotten Champions of 1928,” Bob Tiemann, ed., Mound City Memories –Baseball in St. Louis (Cleveland: SABR, 2007), 41-44.

24 “St. Louis Stars Beat Louisville Black Caps to Sweep Series, 6-0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 16, 1930: 18, accessed from Newspapers.com.

25 “Nashville in St. Louis for 5 games,” Chicago Defender, August 23, 1930: 9.

26 For a detailed account of the 1930 NNL Championship Series, see “St. Louis Wins 1930 Series in Seven Games,” in Robert L. Tiemann, ed., St. Louis’s Favorite Sport (St. Louis: SABR, 1992), 48-51.

27 “St. Louis Ball Fans Fete Flag Winning Stars,” Chicago Defender, October 11, 1930: 9

28 “A.B.C.’s Return Home for Opening Game with St. Louis Stars Friday Night, June 26,” Chicago Defender, June 27, 1931: 8.

29 “The St. Louis Stars Are the World’s Champion Negro Baseball Team,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat Sun

34 Florida State Population Census, 1945, West Palm Beach, accessed from MyHeritage. Library Edition.

35 John E. Reese obituary, Washington Evening Star, October 6, 1966: 31: B-7, accessed from Genealogybank.com.

Full Name

John Edward Reese

Born

April 19, 1895 at Pensacola, FL (USA)

Died

October 5, 1966 at Washington, DC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.