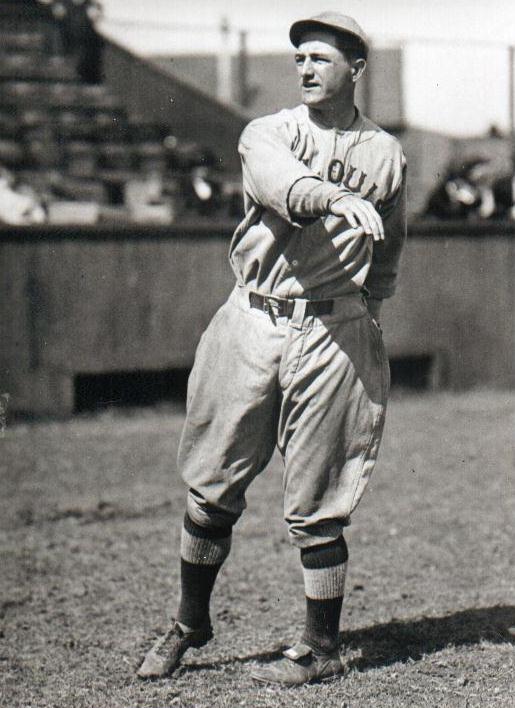

Milt Stock

From the hot corner, Milt Stock made vital contributions towards the Philadelphia Phillies’ first two pennants. As a second-year player in 1915, he took over third base responsibilities when Bobby Byrne suffered a serious injury during the home stretch, and helped the Phillies capture their first NL flag. For another decade, with several teams, he was arguably the finest NL third baseman of the era after Heinie Groh. Stock’s baseball career then turned to skippering minor-league teams, and eventually he returned to the majors as a third-base coach. In this capacity with Brooklyn in 1950, he controversially waved Cal Abrams home in a memorable pennant-deciding loss to Philadelphia’s Whiz Kids.

From the hot corner, Milt Stock made vital contributions towards the Philadelphia Phillies’ first two pennants. As a second-year player in 1915, he took over third base responsibilities when Bobby Byrne suffered a serious injury during the home stretch, and helped the Phillies capture their first NL flag. For another decade, with several teams, he was arguably the finest NL third baseman of the era after Heinie Groh. Stock’s baseball career then turned to skippering minor-league teams, and eventually he returned to the majors as a third-base coach. In this capacity with Brooklyn in 1950, he controversially waved Cal Abrams home in a memorable pennant-deciding loss to Philadelphia’s Whiz Kids.

Milton Joseph Stock was born on July 11, 1893, in Chicago, the only child of Ferdinand and Catherine Stock. His father emigrated from Bohemia as a child, and worked as a bookbinder. His Irish-American mother was an Illinois native.

As a youngster, Stock played ice hockey and basketball, boxed, and raced famed speed skater — and fellow Chicagoan — Ed Lamy.1 He played three years of baseball at St. Ignatius College Prep, then joined the Lawndale semipro team in 1910.2 Joe Kutina recruited him for the Class C Fond du Lac (Wisconsin) squad where Stock made his professional debut in 1911, playing shortstop. Crazy Schmit, scouting for John McGraw, saw Stock in action, and signed him to a Giants contract.3

The 18-year-old Stock reported to New York’s training camp in 1912, showed promise, but was optioned to Buffalo. Again, at 1913’s spring training, McGraw considered Stock not ready for fast company, and sent him to Mobile. In Alabama he hit .281, second among Sea Gull regulars, and led Southern Association shortstops in both putouts and errors.4 Stock also met Mobile native Myrtle McNamara. Two years later the young couple married. Son Milton Jr. arrived in 1917, and daughter Myrtle (“Dickie”) in 1919.

The Giants cruised to a pennant in 1913 and called him up for the season’s final week. Stock went 3-for-17 at the plate and, playing short, committed two errors in each of his first three games. He saw no World Series action as the Giants lost to the Athletics in five games.

Buck Herzog and Tillie Shafer spilt third base duties for New York in 1913. That offseason McGraw traded Herzog and Shafer quit the sport. Consequently, in 1914, Stock took over third base duties for the Giants.

The right-handed Stock stood 5-foot-7 and weighed 150 pounds.5 His most distinguishing physical characteristic were his thick “piano” legs.6 Sportswriters labelled him “chunky” to reflect his muscular build.7 Considered “one of the quietest players in the game,” he was slightly deaf in his right ear.8 As his rookie campaign unfolded, the “earnest, conscientious working youngster” won praise for being “the embodification of grit and sand.”9

On August 12, New York led a crowded NL pack by 6½ games. Then the hard-charging Boston Braves arrived at the Polo Grounds and swept a three-game series. McGraw benched Stock and placed veteran Eddie Grant at third. The change did not alter the trajectory of the 1914 pennant race; the Miracle Braves eventually eclipsed New York by 10½ games.

After the season, Sporting Life editor Francis Richter pointed to “the failure of Milton Stock to fill the place of Shafer … and Herzog” as one of the reasons for the Giants’ downfall.10 But Stock’s retrospectively calculated OPS+ of 103 in 1914 isn’t significantly less than Shafer’s (117) and Herzog’s (109) 1913 performances, while slightly above Grant’s (94) 1914 mark. Defensively, particularly by range factor, Stock compares even more favorably to his Giant peers.

Despite Stock’s credible rookie performance, McGraw sought a veteran presence at the hot corner. That winter he offered Phillies manager Pat Moran cash plus three players — from a list of 18 in the Giants’ organization — in exchange for Hans Lobert. On January 4, 1915, to finalize the deal, Moran selected Stock, pitcher Al Demaree, and catcher Bert Adams.11

In a housecleaning of a long-underachieving squad, the Phillies also dealt mainstays Red Dooin and Sherry Magee that offseason. As a result, Philadelphia sportswriter William Weart observed, “Moran starts out with a team which is not rated to make much noise in the National League race.”12 But Philadelphia’s new leader rejuvenated the squad with a disciplined and focused spring training, which carried into the 1915 season. “Moran has made teamwork the paramount idea,” Stock remarked.13

Veteran Bobby Byrne opened the season as Philadelphia’s third baseman. Stock played sporadically, making only seven starts until August 23, and batting only .200. But that day, in the first game of a doubleheader against the visiting Cubs, an errant throw to third broke the little finger on Byrne’s left hand.14 Byrne was hitting only .208, but his .969 fielding percentage eventually led major-league third base regulars in 1915.

Stock took over third base duties and Byrne’s leadoff spot in the batting order. The Phillies proceeded to win 31 of their remaining 44 games. Stock hit and fielded well, finishing the season with a .260 average and a .971 fielding percentage at third. Along with Ed Burns, who took over starting catching duties after Bill Killefer’s arm went dead in early September, Stock earned considerable praise for helping the Phillies to earn their first pennant.

The Phillies took the World Series opener against the Red Sox, then proceeded to lose the next four games, each a tight battle decided by one run. Stock acquitted himself reasonably well. He bobbled a potential double-play grounder in Game One, which paved the way for a Boston run. In Game Two, he “drew a wild ovation from the crowd” when he snared Jack Barry’s sharp hopper, and made “a magnificent throw while half in the air” to retire the Red Sox second baseman.15 Stock led off Game Three with a hustling double but his mates could not drive him home. He again led off Game Four with a hit. Left fielder Duffy Lewis slightly fumbled the ball and Moran, coaching first, waved the churning Stock to second. Lewis recovered, and his accurate throw cut him down. Yet these were his only two hits in the Series. In Game Five, with Philadelphia ahead 4-2, Boston’s Del Gainer led off the eighth inning with an “awkwardly bounding ball” down the third base line.16 Stock “let the ball play him a bit, instead of playing the ball.”17 Gainer beat Stock’s throw to first, the play ruled a hit. Lewis homered to tie the affair, and Harry Hooper homered again in the ninth to clinch the championship for Boston.

“I play a very deep third base,” Stock observed later in his career. “By playing deep I can cover more ground toward short stop. He in turn can move further toward second base and between us we can make the left half of the infield tighter defensively.” Also, he explained, “Every so often a hard hitter cuts loose with a ball directly over the bag.” A third baseman playing in would see these go down the line as doubles, “but if he plays deep enough, he can knock down some of these.”18

Stock possessed a strong arm. Contemporary accounts often had him throwing out runners at first with balls that took him well into foul territory.19 Or, when a diving stop found him “squatting on terra cotta” or “propped on his left elbow,” he still snapped throws to second to force baserunners.20 He aggressively charged bunts and frequently made thrilling one-handed plays to nail batsmen at first.21 In 1924 longtime Philadelphia sportswriter Bill Brandt opined, “Stockie comes in for those mean slow rollers better than any other hot corner policeman in either league, except possibly Joe Dugan.”22

An April 21, 1916, play against the Giants illustrates Stock moving in towards an anticipated bunt, and the teamwork of Moran’s Phillies. Demaree walked Benny Kauff and Fred Merkle to begin the bottom of the second inning. “Eddie Roush was ordered to sacrifice. The former Fed rolled a perfect bunt toward third. Without a moment’s hesitation Milton Stock pounced on the ball and, instead of looking at first, whipped it over his shoulder to third. In the meantime, anticipating the play, [Dave] Bancroft had run over from short and covered the bag. The play was executed so quickly and surprisingly that Kauff, who had been at second, was an easy force out, and the beautiful bunt had gone for naught.”23 Demaree escaped the inning unscathed and the Phillies went on to win, 6-2.

Philadelphia battled down the stretch with Brooklyn for the 1916 NL flag. Bancroft pulled a tendon in the first game of a doubleheader against the Robins on September 30, but hobbled his way through the match. Philadelphia won, 7-2, and moved in front of Brooklyn by a half game. But Bancroft exited the second game early, his season over. Stock moved to short, and Byrne took over at third. Rube Marquard bested Pete Alexander in the afternoon affair, putting Brooklyn back ahead by a half game. Philadelphia finished the season with six games against Boston. Stock committed four errors at short in the series. The Phillies won only two of the six, and finished 2½ games behind the Robins. Stock provided an OPS+ of 105 for the season and, despite his difficult stint at short, compiled a .955 fielding percentage at third, well above the league average of .938 at the position.

The Phillies again finished second in 1917 but, after a July swoon, never threatened the Giants for the pennant. Tightfisted Philadelphia president William Baker dealt Alexander to the Cubs that offseason for two marginal players and $55,000. The Phillies sank into a distant sixth place in 1918. Stock provided steady but unspectacular play: an OPS+ of 104 in 1917 and 90 in 1918, and average defensive metrics. To support the war effort, Stock worked at a Mobile shipyard after the early conclusion of the 1918 campaign.

Prior to each season, Stock held out: for more pay in 1917 and for a contested bonus in 1918. Baker, continuing the fire sale of the team’s talent, put him on the trading block. In January 1919, Stock, Dixie Davis, and Pickles Dillhoefer were dealt to the Cardinals for Doug Baird, Gene Packard, and Stuffy Stewart. With his new team, Stock again held out, before coming to terms that April.

St. Louis finished last in the NL in 1918, and soon into the 1919 season, the team purchased shortstop Doc Lavan. Cardinals manager Branch Rickey moved his existing shortstop — budding superstar Rogers Hornsby — to third, and planted Stock at second. The Cardinals infield played well, but behind weak starting pitching the team finished seventh. Stock earned high praise from St. Louis sportswriters and fans for his unflagging efforts. Usually batting behind Hornsby in the fifth spot of the order, he hit .307, and achieved a career-high OPS+ of 124. Splitting his time between second and third, he was a plus defensive player.

True to form, Stock didn’t immediately come to terms in the spring of 1920. As he played offseason ball in Mexico and Cuba, and then kept in good condition in Mobile, Rickey was unconcerned. But the Cardinals’ leader did discuss a trade with McGraw involving Stock and Giants third sacker Heinie Zimmerman. The deal never happened. St. Louis improved to a fifth-place finish. Stock contributed another fine offensive campaign, hitting .319 with an OPS+ of 115. Defensively, playing exclusively at the hot corner, he led NL third baseman with 300 assists, but both his fielding percentage and range factor were below league norms. After the season, he managed a group of barnstorming Cardinals.

“Nursing his usual spring grudge over salary or something,” as The Sporting News reported in March 1921, Stock held out for the fifth consecutive year.24 The Cardinals stumbled out of the gate, going 5-15 over the season’s first month. Stock hit only .216 with five RBIs in this span. Then St. Louis caught fire, going 82-51 over the remainder of the season to finish in third with an 87-66 record. Stock recovered from his slow start to hit .307, with an OPS+ of 100. Never possessing an outstanding lateral range at third, he continued to fall behind league defensive norms.

As soon as the 1921 season concluded, Stock again led a flock of barnstorming Cardinals. Their journey began at Sportsman’s Park with a five-game series against the St. Louis Giants of the Negro National League. The series did not sit well with some in the Mound City, due in large part to racial attitudes of the era. “In the eyes of the average white St. Louis fan,” reported The Sporting News, “the stunt was bad stuff.”25

A week later, the same journal reported that Rickey stated “that Stock, by reporting late and out of condition, cost his team at least 15 victories.”26 Stock pushed back against the outlandish claim. Rickey denied the quote attributed to him, insisting that Stock’s poor early form was but one of a handful of factors dooming the Cardinals in the 1921 race. Stock found this revised take unsatisfactory, and reportedly told Rickey “that the third base play didn’t damage the team’s chances half so much as the way the team was managed.”27

Nothing in the spat suggested Rickey objected to the integrated series. Indeed, Stock stated the club’s officials granted him permission to play the Giants. Instead, Rickey’s objections seemed more grounded in the lack of control clubs had over the barnstorming activities of their players, a controversy that also played out that fall between Babe Ruth and Kenesaw Mountain Landis. A flurry of trade rumors whirled about before Stock repented.

Stock reported to camp on time in 1922 and started the season well. Despite being moved around in the batting order, he finished the campaign with a .305 average and an OPS+ of 102. But, despite Hornsby’s Triple Crown, the Cardinals again finished third.

At the plate, Stock began as a pull hitter, but early in his Phillies career Pat Moran had worked with him to shorten his swing and punch balls into right.28 “A mite of a fellow with a big bat,” Stock’s bunting and hit-and-run capabilities were praised by sportswriters.29

In 1923, with Hornsby usually batting third and Jim Bottomley cleanup, Stock again occupied the fifth spot in the Cardinals’ batting order. For the first time in five seasons he hit under .300 and his OPS+ of 86 was the lowest mark of his career to that juncture. But with two future Hall-of-Famers hitting in front of him, Stock made the most of his opportunities and drove in a career-high 96 runs.

St. Louis’s contract offer for the 1924 season included a pay cut. Stock held out again. Rickey responded with an earnest effort to deal him and, on April 25, traded him to Brooklyn for catcher Mike González and “something like $7,500.”30 “We’re no longer a second-division club,” said Robins first baseman Jack Fournier after the deal.31 Brooklyn did jump from its 76-78 showing in 1923, challenging the Giants for the pennant before falling 1½ games back with a 92-62 mark. Yet that was mostly due to Dazzy Vance’s pitching Triple Crown, and fine campaigns from Fournier and Zach Wheat. Stock started the season at a .300 clip, but soon sustained a nagging left heel injury which affected his ability to stride into pitches.32 He finished the year with a .242 average (an OPS+ of 55).

Brooklyn stumbled out of the gate in 1925, and Wilbert Robinson shook up the lineup. After initially benching Stock, the Robins’ manager placed the veteran at second base to replace the slumping Andy High. Stock promptly went on a tear at the plate, capped by a record four consecutive four-hit games that brought his average to .404 by July 4.33 He cooled off later in the summer, and completed the season with a career-high .328 average and a career-high 98 runs scored. Yet he remained a Punch-and-Judy hitter, amassing only 38 extra-base hits, a league-leading 164 singles, and an OPS+ of 100. He proved an adept fielder at second, with the third-best fielding percentage in the league at the position. But, a Brooklyn scribe noted, “Milton simply could not grasp the knack of co-operating with his shortstop on a double play and this weakness cost the Robins a half a dozen games.”34 Hyperbole perhaps, but Brooklyn turned 20 fewer double plays than the league average. The Robins fell back in 1925, finishing with a 68-85 mark.

In later years, it was frequently reported that “a collision with Lou Gehrig during an exhibition game in 1926 cut short” Stock’s major-league career.35 Yet this tale seems to have no basis in fact. First, as the year began, Stock returned to his hold-out ways. Robinson stated, of the two veterans holding out that spring, “We finished seventh with both Wheat and Stock last season and we can finish seventh this year without them.”36 In late March, Stock agreed to a $9,500 salary for the season and reported.37 The Robins did engage the Yankees in a lengthy southern series that spring, and there is reporting of Stock playing unimpressively at second, but none of a collision with Gehrig. Stock’s poor performance carried into the first two games of the season. Robinson put journeyman Snooks Dowd at second before handing the job to rookie Johnny Butler. Then he handed Stock his unconditional release.

Stock returned to Mobile to play third and manage their Southern Association squad. While his playing career petered out in 1930, he managed minor-league teams through 1943. Most notably, from 1936 through 1942, he led the Class B South Atlantic League’s Macon Peaches. At Macon, he helped develop future major-leaguers Johnny Rucker, Eddie Stanky, and Andy Pafko.

Stanky, a Peach from 1939 through 1941, credited Stock as one of his greatest influences, and for molding him into a leadoff hitter.38 While at Macon, Stanky courted Myrtle (“Dickie”) Stock and, in April 1942, married the boss’s daughter. Shortly after the wedding, Stock sold his son-in-law to the American Association’s Milwaukee Brewers for a $3,000 profit.

In 1941 Macon became a Cubs affiliate. Two seasons later, Chicago transferred its Class B farm team to Portsmouth, Virginia. Stock managed this team as well. In 1944 the Cubs brought Stock back to the majors, to join Charlie Grimm’s coaching staff. The Cubs captured the NL flag in 1945 but soon regressed. After finishing in the cellar in 1948, the Cubs marked several coaches, including Stock, for re-assignment. Rather than take a scouting role, he signed with General Manager Branch Rickey’s Dodgers to coach third.

Stock joined the most aggressive base-running team in baseball. From 1946 to 1948, Brooklyn stole more bases than any other major-league team, and were above average in other statistical measures (bases taken, extra bases taken percentage, outs on base). But in one regard — runners on second scoring on a single, Brooklyn was notably apprehensive. Only 68% of the time did a Dodger on second score in this scenario, with only the Cubs and Phillies claiming a lower percentage.39

Such trends continued into Stock’s tenure. After losing two critical mid-August games to Philadelphia in the tight 1949 race, Brooklyn fans pointed “to Stock as the timid soul who handed the Phils two victories with his stop signs.”40 The Dodgers went on to win the pennant, but lost the World Series to the Yankees.

In 1950 Brooklyn overcame a nine-game deficit on September 18 to close Philadelphia’s lead to a single game coming into the season’s finale between the clubs on October 1 at Ebbets Field. If the Phillies won, they would clinch the pennant. If the Dodgers prevailed, they would force a best-of-three playoff.

With the score tied at 1-1, Robin Roberts walked Brooklyn’s lead-off hitter Cal Abrams to begin the bottom of the ninth. Pee Wee Reese then lined a single to left, Abrams stopping at second. Duke Snider came to the plate. The Phillies expected him to bunt, with second baseman Granny Hamner staying close to the bag, and center fielder Richie Ashburn playing shallow. Yet Brooklyn manager Burt Shotton allowed Snider to hit, and the Dodger center fielder dropped a single in front of Ashburn.

Stock waved Abrams home. Ashburn charged the ball and made a perfect throw. Catcher Stan Lopata blocked the plate several feet up the third base line, and Abrams pulled up just short of him, making the inning’s first out. Roberts intentionally walked Jackie Robinson. Carl Furillo popped up. Gil Hodges flied out. Dick Sisler won the pennant for Philadelphia with a three-run homer in the top of the tenth.

In the aftermath, Stock expressed no regrets: “We have been scoring on plays like that all season against the Phillies because Ashburn is not a great thrower. Furthermore, Reese was coming around fast, and if I had held up Abrams there might have been a jam at third base.”41 Shotton directed a note of responsibility towards Abrams: “He gets on base, and he’s fast enough, but somehow he don’t run the bases right and you have trouble moving him around. It takes two hits to score him from second base.”42 Abrams: “I think they should have held me at third.”43 Ashburn, years later: “If Stock had held Abrams at third, the Dodgers would have had the bases loaded and nobody out and Roberts would have had to pitch to Robinson, the best clutch hitter in a lineup of great hitters.”44

Along with Shotton and Rickey, Stock was forced out that offseason. Rickey took over the general manager reins in Pittsburgh, and Pirates manager Billy Meyer recruited Stock.45 After one season coaching third for Pittsburgh, Stock underwent a back operation, and served the team in an advisory role in 1952.46 At the end of that season, he stepped down, ending a four-decade career in baseball.

Stock retired to a quiet life in Alabama. On July 16, 1977, he died in his Montrose home. He was survived by his wife Myrtle, son Milton Jr., daughter “Dickie,” six grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. Stock was buried in Catholic Cemetery in Mobile.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Stock’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, and the following sites:

Notes

1 “Milton Stock Real Find Among Majors This Year,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 1914.

2 “Promising Youngsters Who Will Be Tried Out in South by Giants,” New York Press, January 28, 1912; John P. Carmichael, “Sturdy Stock—It’s No-Wilt Milt, Collared by Cubs as New Coach,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1944, 7.

3 Edgar G. Brands, “Between Innings,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1931, 4.

4 Fielding statistics from Francis C. Richter, ed., The Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1914 (Philadelphia: A. J. Reach, 1914), 274.

5 For contemporary accounts of his height and weight, see “Promising Youngsters” and “Answers to Queries,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 19, 1919.

6 James M. Gould, “Milt Stock Reports, But Myers Is Still a Cardinal Absentee,” St. Louis Star and Times, March 7, 1923; Thomas Holmes, “Milton Stock Breaks Hit Streak, But Robins Twice Gobble Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 5, 1925.

7 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Stocks’ Swats and Throw Saved Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 1, 1917; James C. Isaminger, “Before July 4, Phils Will Regret Trade of Stock, Says Quaker Scribe,” St. Louis Star and Times, January 30, 1919.

8 James M. Gould, “Movie Serial Battle Goes to Giants, 4-2; Three Athletes Hum,” St. Louis Star and Times, June 21, 1919

9 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, May 2, 1914, 7; A.R. Goldberg, “Snodgrass Used as Whip on Giants,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1914, 1.

10 The Editor [Francis Richter], “The Complete 1914 Record,” Sporting Life, October 17, 1914, 7

11 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Pat Moran Cleaning House with Swapping of Players to Start New Year,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 5, 1915.

12 William G. Weart, “Writers’ Banquet Ends Stove League,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1915, 1.

13 “Every Philly Player Vows Team Will Win,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, October 2, 1915.

14 William G. Weart, “Now Comes the Real Test of Whole Season for Phillies,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1915, 1.

15 Frank G. Menke, “Pitcher Foster Goes Down in History as a Hero,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 10, 1915.

16 “Foster Pitched Fewer Balls Than Phils’ Two Hurlers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1915.

17 Damon Runyon, “Golden West Figured in Victory,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 14, 1915.

18 “The Advantage of Playing Deep at Third,” undated magazine article in Stock’s Hall of Fame file.

19 Thomas S. Rice, “Labor Day Baseball Games May Fail for Lack of Men,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 14, 1918; Thomas S. Rice, “Heathcote’s Canning Disapproved by Fans,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 27, 1919.

20 Ed Cunningham, “Watson Holds Cardinals to Four Scattered Hits,” Boston Herald, August 6, 1920; “Cardinals Humble Champion Giants,” New York Times, June 20, 1922.

21 Ed Cunningham, “Sullivan’s Hit Causes Even Break at Tepee,” Boston Herald, September 17, 1920; Thomas Holmes, “Griffith’s Catch Helps Turn Back the Reds, 5-2; Johnston Out for a Week,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1924.

22 Ralph Davis, “Sports Chat,” Pittsburgh Press, September 6, 1924.

23 Bozeman Bulger, “Yankees Slam Senators and Are Now Tied with Red Sox for First Place,” New York Evening World, April 22, 1916.

24 “Cards Start Games with Corners Open,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1921, 1.

25 “Too Much New York Say St. Louis Fans,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1921, 1.

26 “Stock Tries to Even Up for What He Lost,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1921, 1.

27 “Bob Quinn Home to Take Up Old Grind,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1921, 1.

28 William G. Weart, “Phils in Condition to Show Best Parts,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1916, 1.

29 Francis J. Powers, “Veteran Pfeffer Mystifies Tribe,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 29, 1923; “Robbie Reconstructs His Pitching Staff to Meet Stiff Opposition,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 12, 1925.

30 Thomas Holmes, “Squire Ebbets is Doing Christmas Shopping Early,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 28, 1924.

31 Thomas S. Rice, “New Third Baseman Makes Victory Possible by His Single in the Eleventh,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 1, 1924.

32 Thomas Holmes, “Milton Stock Tells Why His Hitting Dropped to Almost Nothing in 1924,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 25, 1925.

33 Per the Batting Streak Finder within Baseball-Reference’s Play Index. These statistics presently stretch back to the 1913 season.

34 Thomas Holmes, “Robins Seem to Be Strengthened for Next Year,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 17, 1925.

35 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977, 54.

36 Thomas Holmes, “Buck Wheat Has Not Yet Come to Terms; Chatter at the Camp,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 27, 1926.

37 Thomas Holmes, “Robins Quit Clearwater; Deal for Eddy Sicking Another Disappointment,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 26, 1926; Thomas Holmes, “Milton Stock Finally Accepts Robbie’s Terms; Will Join Team Sunday,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 27, 1926.

38 Clay Felker, “Diamond Dossier: Eddie Stanky,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1951, 13.

39 Baserunning statistics courtesy of Baseball-Reference’s MLB Baserunning/Misc pages.

40 Bill Roeder, “Fans Err Calling Stock Dodger Goat,” August 18, 1949, newspaper (likely from the New York World-Telegram) clipping in Stock’s Hall of Fame file.

41 “Milt Stock Explains Why He Sent Abrams Home in the Ninth,” Allentown Morning Call, October 2, 1950.

42 Bill Roeder, “’Paradise: Should Have Cal Have Been Held at Third,” October 2, 1950, newspaper (likely from the New York World-Telegram) clipping in Stock’s Hall of Fame file.

43 Ibid.

44 Richie Ashburn, “The Way We Were,” Philadelphia Daily News, September 27, 1990.

45 Jack Hernon, “Ex-Dodger Aide Signs with Bucs,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 12, 1950.

46 Jack Hernon, “Coach Milt Stock Quits Bucs Because of Health,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 26, 1952.

Full Name

Milton Joseph Stock

Born

July 11, 1893 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

July 16, 1977 at Fairhope, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.