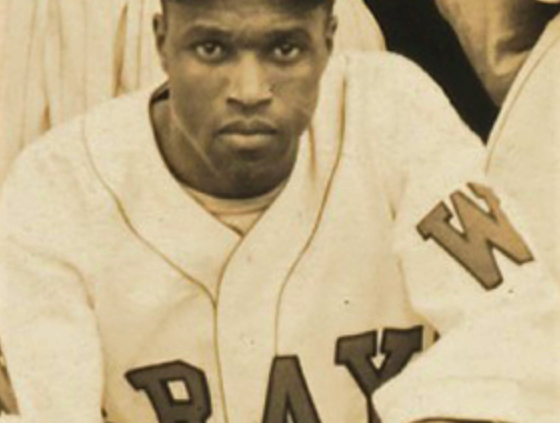

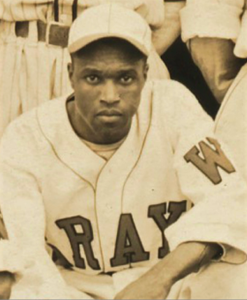

Rocky Ellis

Rocky Ellis is one of the many Negro League players whose statistics tell only a fraction of the full story. Sandwiched between official league contests were the numerous battles against teams of varying skill. These games made up the meat of a player’s diet but usually are not taken into consideration when the breadth of a career is examined. Nonetheless, it was in these games that a player’s reputation, fan base, and livelihood often were built.

Rocky Ellis is one of the many Negro League players whose statistics tell only a fraction of the full story. Sandwiched between official league contests were the numerous battles against teams of varying skill. These games made up the meat of a player’s diet but usually are not taken into consideration when the breadth of a career is examined. Nonetheless, it was in these games that a player’s reputation, fan base, and livelihood often were built.

Ellis is best known for his tenure with Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars, and he made a name for himself pitching for the 1934 squad in the Negro National League II Championship Series. The diminutive, scrappy right-hander was described by his submarining teammate, Webster McDonald, as “a little guy with a big heart.” McDonald also praised Ellis as one of the few pitchers who could get the mighty Josh Gibson out on a regular basis.1

Raymond Charles Ellis was born on January 26, 1911, in Darby, Pennsylvania. His father, Washington Ellis, was born in either 1871 or 1873 in Virginia as recorded by the 1910 and 1920 censuses respectively. His mother, Mary Hudson, was born in October of 1874, also in Virginia. The two were married on April 11, 1894, in Nottoway, Virginia, and had nine children together, including seven daughters – Mattie, Edna, Hannah, Lillie, Marion, Dorothy, and Jewcella – and two sons, George and Raymond. Raymond was born eighth of the nine children and a full 20 years separates the birth of their second child, Edna, and their last, George. Mysteriously, their first child, listed as Mattie Hill, was born in 1886, meaning that Mary, her mother, would have been 12 at the time of her birth. Mattie died in 1918 at the age of 32, and Washington and Mary Ellis are listed as her parents, but she is not mentioned in the 1900 or 1910 censuses as living with the couple.2

The Philadelphia Tribune described Ellis as “the peppy mascot” and “the youngster scurrying about the field” when Ellis toted bats for the legendary Hilldale clubs of the mid 1920s.3 The 13-year-old Ellis had a front-row seat as the Hilldale Club, or Daisies as they were often called, played in the first two Negro League World Series, winning on their second try in 1925. As a 16-year-old in 1927, Ellis was inserted into left field in the seventh inning of an 11-3 blowout in a game against the Judy Gans All-Stars.4 It was Ellis’s first Negro League appearance. The following season, in 1928, he was given a chance to compete for a spot in the outfield, but opportunities were slim as stalwarts Oscar Charleston, Otto Briggs, Clint Thomas, and Bill Johnson all stood in his path.5 Ellis was seldom used, as his two error-free innings in center field and a base hit in his lone plate appearance attest. The Philadelphia Tribune lauded Ellis as “roaming far and wide to show that he can play ball as well as perform mascot duties.”6 Ellis and two teammates were released by the club in late July for refusing to take their jobs seriously. Perhaps this is not too surprising, since Ellis was just 17 at the time.7

In May of 1928 Ellis signed on with one of the top Black semipro teams in Philadelphia, the Emerald Colts, but his time with the Colts was short-lived and by July he was a regular with the Inter-Urban Twilight League powerhouse Darby Phantoms.8 Ellis found his footing with the Phantoms as evidenced by a two-game set played on October 6 in which he twirled a four-hit, 6-0 shutout against Colwyn in the early match and showed up in the second game in right field, smacking two hits in a surprise 6-6 tie with the far superior Hilldale Club.9 Ellis was the team’s vital cog and led it them to consecutive championships in 1929 and 1930. In the 1929 finale, he toed the rubber for the clincher against Sandy Conway’s Colwyn team, coming through with a 3-2 complete-game victory in which he limited Colwyn to just three hits.10 The following season’s playoff performance was even more spectacular as Ellis took the hill for both games of a two-game sweep, once again against the Colwyn club, taking the first game, 7-3, and the clincher, 4-1, in the best-of-three series. Ellis allowed just six hits in the winner, chipped in with an RBI triple, and scored the winning run in the second inning of the contest.11

Showing off his athleticism, Ellis also spent some time on the gridiron in 1930 as he finished out the year with the Philadelphia-based Progressive Tornadoes. In a losing effort against a much better Mauch Chunk team, Ellis was praised for his effort at right halfback and punter.12 Ellis returned his Phantoms baseball contract unsigned in 1931, but was back with his comrades by early summer. He played left field in a June 4 contest against Daugherty C.C. and rapped two hits in the matchup.13

White sports promoter, sporting goods owner, and Philadelphia native Harry Passon built Passon Field at 48th and Spruce Streets in Philadelphia to support his Philadelphia Bacharach Giants team in 1931; and, after his brief reunion with the Phantoms, Ellis signed on with the team. Passon Field was a state-of-the-art diamond that featured seats for 6,000 spectators and lights to support night baseball.14 Ellis was in fine form on June 21 as he spun a complete-game seven-hitter in a 4-3 victory over a team from Camden, New Jersey.15 Philadelphia Stars owner Ed Bolden, stating that the City of Brotherly Love could not support two Black teams, helped to block Passon’s team from gaining admission to the Negro National League in 1931. Bolden’s interference did not deter Passon, and his Bacharach Giants trudged forward during the 1931 season.16 The Giants were finally granted admission into the NNL in 1934 but withdrew from the league the following season, citing violence at Passon Field as the cause. The team pressed on as a semipro squad until it finally disbanded subsequent to Passon’s death in 1942.17

Ed Bolden took control of the Darby Phantoms prior to before the 1932 season in hopes of repeating the success he had experienced with Hilldale, which he had molded during the previous decade from a group of young amateurs into a high-class professional championship team.18 Ellis rejoined the Phantoms for the third time as it was announced on April 5 that he was expected to report for the team’s practice and begin the season on May 7.19 The versatile Ellis shined early in the season, banging out two hits and playing left field in a loss to Chester. In a doubleheader vs. the Lancaster Red Sox, Ellis had two more safeties and recorded eight putouts at first base in the opener and played a flawless third base in the nightcap with three assists, although the Phantoms lost both games.20 The Phantoms never lived up to Bolden’s high hopes and struggled to compete with the semipro teams they lined up against.21 Bolden abandoned the Phantoms after the season, leaving them in the lurch and without direction. By early 1933, he was openly advertising his newly formed Philadelphia Stars team. Bolden asserted that he would “land a team which will make the city forget its baseball headaches of recent seasons.”22

Ellis was not prepared to rejoin a Bolden-owned team just yet. Instead, he suited up for the Brooklyn Cuban Giants, playing out of Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1933.23 After an August 16 game against the Waterville All-Stars, the Waterville (Maine) Morning Sentinel praised Ellis, declaring, “[T]his Ellis is just about as classy a pitcher as ever invaded this fair town. The smoke artist had a barrel of speed, he was rifling ’em up like cannonfire, the pellet looked like a pea, and he had control aplenty.” Ellis completed the game, surrendering just two hits in a lopsided 11-1 victory.24 Ellis finished out the year in style, traveling to Puerto Rico to play for the eventual championship team, Estrellas de Ramirez. The loaded team featured Josh Gibson, Rap Dixon, Ted Page, Jim Williams, and Bill Holland.25 W. Rollo Wilson of the Pittsburgh Courier declared that “the two best pitchers in Porto Rico last winter were Slim Jones and Rocky Ellis.”26 Both pitchers joined Ed Bolden and his Philadelphia Stars for the 1934 campaign in the Negro National League II (NNL2).

Ed Bolden, ever the marketing genius, used the Black press to help promote his newly minted Philadelphia Stars in their inaugural season of 1933. Players came from far and wide to join his new club, including veterans Biz Mackey, Jud Wilson, Dick Lundy, Rap Dixon, and Webster McDonald.27 The Stars began as an independent team that maiden season but were granted admission into the NNL2 in 1934, to compete against such legendary teams as the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Chicago American Giants. Thanks to Ellis’s penchant for never straying far from Philadelphia, his first season in the NNL coincided with the Stars’ magical championship ride of 1934.

In what may have been Ellis’s first appearance for the Stars, he started and pitched the first three innings of an April 15, 1934, victory over the Raphael team that had won the previous year’s Philadelphia League championship. The Stars won the game, 9-3, and Ellis struck out three batters in his three innings of work.28 The grand opening of the NNL2 season took place on May 13 in Newark, New Jersey, with a doubleheader matchup against Dick Lundy’s Newark Dodgers. Ellis was in fine form in the nightcap, restricting Newark to three hits in a 4-1 complete-game victory after hurler Lefty Holmes had taken the first game, 5-4, with Slim Jones finishing out the ninth inning.29 Holmes and Ellis traded places in a June 24 double bill against the Cleveland Red Sox. Ellis won the first game, 2-1, limiting Cleveland to six hits and outdueling eight-time all-star Bill Byrd, while Holmes captured the second game in a 9-0 laugher.30

The Stars’ biggest rival in 1934 was the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a team that featured five future Hall of Famers and whose spectacular 47-27-3 record was just barely eclipsed by the Philadelphia squad. On July 12 Ellis was on the winning side of a gutsy 7-6 contest against the Craws in which he went the distance while surrendering 10 hits and outlasting Pittsburgh starter Sam Streeter to salvage a split of that day’s doubleheader.31 Ellis’ dominance continued on July 18 in a 7-1 drubbing of the NNL2 rival Nashville Elite Giants, led by Candy Jim Taylor.32

In what turned out to be a Championship Series preview, the Stars took on the Chicago American Giants on July 28 and Ellis limited the Windy City gang to seven hits in a 9-3 victory.33 Dave Malarcher’s Chicago American Giants, led by future Hall of Famers Turkey Stearnes, Willie Wells, Willie Foster, and Mule Suttles, secured a spot in the championship series by winning the first half of the NNL2 campaign. The hard-luck Pittsburgh Crawfords had a far superior overall record than Chicago but could not manage to capture either half of the season as the Stars took the league’s second-half title.

When manager and pitcher Webster McDonald credited Ellis as the guy who “won the championship for us” in 1934, he was probably referring to Ellis’s masterful Game Five performance.34 Down three games to one to the American Giants and facing elimination against Rube Foster’s brother, future Hall of Famer Willie Foster, Ellis twirled the game of his life, going the distance with nine strikeouts in a 1-0 masterpiece. The Stars took Games Six and Eight (Game Seven ended in a tie) and finished off the Giants to take home the championship.

The 23-year-old Ellis threw 18⅔ innings in the series, giving up 14 hits with 16 strikeouts and a 2.41 ERA. Notably, he was also the recipient of a fair amount of luck as he also allowed 10 free passes.

The team celebrated its victory at the O.V. Catto Elks Lodge, an all-Black fraternal order in South Philadelphia that also served as a dance hall and boxing and wrestling club. The Philadelphia Tribune singled out Ellis and teammate Jake Stephens, observing that “the boys were so happy that their smiles never left their faces till after two in the morning.”35

The following season was a letdown for the Stars, who could not quite keep up with the powerful Crawfords. Ellis remained in fine form, though, and was praised early in the season by the Chicago Defender, which wrote that he had “profited much by last year’s experience and will be one of the best curve ball throwers in the loop.”36 It was not the only time Ellis’s curve drew attention that season as the Norfolk (Virginia) New Journal and Guide noted in early June that “Rocky Ellis has a sharp-breaking curve and speed a’plenty.”37 Ellis got the nod on Opening Day and pitched seven strong innings in securing a 7-5 win against the Brooklyn Eagles. He also socked one over the left-field fence for a third-inning home run for the victors.38

The Stars were never able to recapture the glory of their 1934 championship season, and the 1936 squad tumbled all the way to last place in the NNL2. The juxtaposition between Ellis’s official records and what was reported by the newspapers at the time is difficult to sort out. In early July the Delaware County Daily Times said of Ellis: “He is recognized as one of the aces of the National Negro League and has been defeated only twice this season.”39 This seems to suggest that Ellis performed much better against nonleague teams, although he did enjoy some success against top clubs. In a career highlight on May 17, Ellis outdueled Satchel Paige and the defending champion Pittsburgh Crawfords by a score of 6-2. It is also noted that the Stars took sole possession of first place on this date.40 A seven-inning, two-hit triumph vs. the New York Black Yankees on September 17, followed by a 10-strikeout, six-hit, 5-3 win over the Nashville Elite Giants more than solidified Ellis’s worth to the team.41

In a tough loss to the Pittsburgh Crawfords on September 26, 1936, Ellis was literally knocked out of the game by Crawfords shortstop Chester Williams. Pittsburgh Courier writer W.B. Wilson painted the picture:

Now Rocky has been one pitcher whom Ches has always had trouble hitting but Saturday he hit him – several ways. Taking an extra tug on his pants the Louisiana boy slammed one of Rocky’s fast ones back at him and almost tore his right foot off, the batted ball bounding across the foul line at third base. The next time up Ches hit another one which nearly amputated Ellis’ left pedal, this time the ball rebounding towards first base. That was enough for Rocky. After being given first aid by the club trainer, he limped from the field, absolutely through for the day.42

Ellis was also married in 1936, to 26-year-old Ophelia Sparrow in Philadelphia.43

The remainder of the decade provided few highlights for the Stars and a distant second-place finish to the powerful Homestead Grays in 1938 was the closest they came to a return to the playoffs. Ellis was still a respected pitcher as was evidenced by the fact that the Philadelphia Tribune exclaimed in early 1938 that he was a “mighty powerhouse despite his slight stature.”44 White sportswriter Jimmy Powers campaigned for Ellis by name – as well as for other Negro League players – in a column in July, his New York Daily News column titled “The Powerhouse,” stating that they were baseball stars who could help the struggling Brooklyn Dodgers.45

At some point during the 1939 season, Ellis was banned from baseball for his refusal to accept a trade to the Homestead Grays. He eventually relented and reported to the Grays for the 1940 season after having taken another winter trip to Puerto Rico to play for the Caguas Criollos.46

The Homestead Grays were league champions of the NNL2 in 1940, but unfortunately Ellis was not with the team at the end of the season to enjoy the spoils. The Pittsburgh Courier had called him “one of the best right-handers in Negro baseball” during his stint with the Grays and he had been firmly entrenched in the starting rotation throughout most of the summer.47 In a game on June 1, Ellis made his presence known from the coaching box, rather than the mound, in a game against his former team, the Philadelphia Stars. On a heads-up play while coaching first base for the Grays in the fifth inning, Ellis yelled to first baseman Buck Leonard, “[T]hrow the ball to second, Buck,” after noticing that baserunner Bill Cooper had failed to touch second base on his return trip to first after a long fly out. Cooper was called out on the play and the Grays won the game, 5-2.48 Ellis was back with the Stars by late August. In a doubleheader against the Memphis Red Sox on September 7, he struggled but managed to pull out a 10-5 victory while scattering 10 hits. In the nightcap he played left field and batted ninth.49

Ellis began the 1941 season with the Brooklyn Royal Giants, a team without a home that traveled across the country in style in their special deluxe bus. The team had journeyed over 30,000 miles the previous season, and Ellis was now along for the ride.50 By all accounts, he held his own and was pitching well in July with complete-game victories over the Collingswood All-Stars and the Red Bank Pirates.51 It was also reported that Ellis defeated the Candy Jim Taylor-led Chicago American Giants that summer.52

Dr. Joseph Henry Thomas had created a paradise for Black entertainment just eight miles out of Baltimore in Turner Station, Maryland, in 1929. It featured an amusement park, a concert pavilion, restaurants, and a beach, but what probably landed Rocky Ellis in 1942 was the 5,000-seat covered grandstand with all the modern conveniences not usually available to Black ballplayers. His team, the Baltimore Grays, sprang up in 1935 and in 1942 the squad was part of the Negro Major League, a short-lived rival of the Negro American and National Leagues.53 The Grays, managed by standout catcher Mickey Casey, demolished the Richmond Hilldales 12-3 on June 7 thanks to a 5-hit complete game victory by Ellis.54 The unstoppable Grays later defeated the Cincinnati Ethiopian Clowns on July 6 for their 16th victory in 17 games.55

Rocky Ellis enlisted in the US Army on June 15, 1942, effectively ending his baseball career. He served in both World War II and in Korea and rose to the rank of master sergeant during his 20 years of service. He was discharged on July 31, 1962, and was living in Richmond, Virginia, by 1985, a city that his parents no doubt had been familiar with.56 His wife, Ophelia Sparrow, passed away in 1985 in Philadelphia. Ellis is listed as widowed on his death certificate, but his wife’s name is mentioned as Evelyn Ellis. It is unknown if he remarried or if this was another name for Ophelia. Rocky Ellis died from aspiration pneumonia due to sepsis on November 15, 1989, at the Metropolitan Hospital in Richmond. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery, a historical African American cemetery in Richmond.57

Rocky Ellis sports a meager 24-24 record in Negro major-league games for his baseball career, but it is obvious that his stamp on the game was much more indelible than that. At the very least, his six years with the storied Philadelphia Stars, when he was often ranked as one of the top pitchers in the league, and his short stints with acclaimed teams like the Homestead Grays and Brooklyn Royal Giants hint at his greatness. Ellis was only 31 when he left baseball in 1942 to join the war, but from his humble beginnings as a 13-year-old Hilldale batboy to his final pitch for the Baltimore Grays, his almost 20 years in the game should ensure that he will always be remembered.

Sources

All statistics, unless otherwise noted, are from Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 John Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1992), 83.

2 Ancestry.com.

3 Philadelphia Tribune, December 29, 1927: 10.

4 “Stars Beaten as Hilldalers Slug the Ball,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 22, 1927: 11.

5 “Charleston and Dalty Cooper Sign With Hilldale,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 31, 1928: 16.

6 “Bolden’s Pets Wreck House of David,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 5, 1928: 11.

7 “Hilldale Players Released,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 28, 1928: A4.

8 “Ellis and Thorpe on Elmwood Nine,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 9, 1929: 10; “Phantoms Tie For Lead in League Race,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 11, 1929: 10.

9 “Phantoms Win and Tie,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 1929: 6.

10 “Darby Phantoms Win League Flag,” Baltimore Afro American, September 21, 1929: 15.

11 “Rocky Ellis Bright Star as Darby Boys Clout Way to Suburban Loop Crown,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 25, 1930: 10; “Darby Phantoms Win Interurban Title,” Delaware County Daily Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), September 22, 1930: 12.

12 “Progressives Bend Knee at Mauch Chunk,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 30, 1930: 10; “Colored Pro team Defeated by 38-6,” Baltimore Afro-American, November 1, 1930: 16.

13 “Interurban League,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 5, 1931: 20.

14 Euell A. Nielsen, “The Bacharach Giants (1916-1929) (1931-1941),” December 1, 2020 https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/the-bacharach-giants-1916-1929-1931-1941/. Accessed February 22, 2023.

15 “Steele, Woodington Share Pitching Honors,” Camden (New Jersey) Morning Post, June 22, 1931: 13.

16 Nielsen, “The Bacharach Giants (1916-1929) (1931-1941).”

17 Nielsen.

18 Courtney Michelle Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2017), 64.

19 “Brice to Captain Darby Phantoms,” Delaware County Daily Times, April 5, 1932: 11.

20 “Chester Tops Darby Phantoms,” Delaware County Daily Times, May 9, 1932: 13; “2 Local Boys Play With Sox,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) New Era, May 9, 1932: 1.

21 Smith, 64.

22 Smith, 70.

23 “Rady Says: Editor,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 25, 1933: 11.

24 “Cubans Win Easily, 11-1,” Waterville (Maine) Morning Sentinel, August 17, 1933: 3.

25 “Rady Says: Baseball in Puerta Rica,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 12, 1934: 10.

26 “Sports Shots: Press Box and Ring Side Here’s Your Old Col Again,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 5, 1934: A4.

27 Smith, 69-70.

28 “Philly Stars Crush Raphael,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 21, 1934: 18.

29 “Philadelphia Stars Win 2 From Newark,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 17, 1934: 12.

30 “Rocky” Ellis Allows 6 Hits in Sunday Tilt,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 28, 1934: 12.

31 “Crawfords and All-Stars Split,” York (Pennsylvania) Gazette and Daily, July 13, 1934: 11.

32 “Philly Stars in Win Over Elites,” Chicago Defender, July 21, 1934: 16.

33 “Stars Drub Bees in City Series Start,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 2, 1934: 12.

34 Holway, 85.

35 “O.V. Catto Elk News,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 25, 1934: 8.

36 “Champion Philly Stars to Open with the Grays,” Chicago Defender, April 27, 1935: 16.

37 “Philadelphians Debating Class of 1935 Stars, Norfolk (Virginia) New Journal and Guide, June 8, 1935: 14.

38 “Phila. Stars Subdue Brooklyn Eagles, 7-5,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 12, 1935: 43.

39 Delaware County Daily Times, July 8, 1936: 10.

40 “Phila. Stars in Loop Lead,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 21, 1936: 12.

41 “Phila. Stars Beat Black Yanks, 3-2,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 17, 1936: 15; “Philly Stars Grab Three: Bolden Nine Beats Yanks Twice and Elite Giants,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 19, 1936: 22.

42 “National Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 26, 1936: A5.

43 Ancestry.com.

44 “Bolden Predicts Pennant,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 28, 1938: 12.

45 “The Powerhouse by Jimmy Powers,” New York Daily News, July 11, 1938: 83.

46 “Outfielder Sends Word He Wants More Money,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 14, 1940: 11; “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 23, 1939: 16.

47 “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 4, 1940: 16; “Grays Will Gun for Pennant With This Group,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 11, 1940: 16; “Homestead Grays Tied By Meteors,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 3, 1940: 16.

48 “Dunn Renamed Manager of Stars, Philadelphia Tribune, June 6, 1940: 11.

49 “Stars Sweep Memphis Series,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 12, 1940: 11.

50 “Brooklyn Royals Tangle with Black Barons in Muny Stadium,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, July 23, 1941: 17.

51 “Royal Giants Rally in Sixth Inning to Nose Out Suburbanites, 3-2,” Camden Morning Post, July 15, 1941: 14; “Pirates Beaten by Royals, 8-4,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, July 19, 1941: 10.

52 “Turner Field Tilt Features Hunter, Ellis,” Munster (Indiana) Times, July 30, 1941: 19.

53 “Dr. Thomas’ Experiment Might Be Salvation of Negro Baseball,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 30, 1942: 16; J.K. O’Neill, “What’s Up with Dr. Thomas? Part 1,” Dundalk (Maryland) Eagle, April 7, 2016, https://www.pressreader.com/usa/the-dundalk-eagle/20160407/281792808180231. Accessed February 22, 2023.

54 “Baltimore Grays Twice Trip Richmond Hilldales,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 13, 1942: 23.

55 “Clowns Downed, 8-2, By Baltimore Grays,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 7, 1942: 2.

56 Ancestry.com.

57 Ancestry.com.

Full Name

Raymond Charles Ellis

Born

January 26, 1911 at Darby, PA (USA)

Died

November 15, 1989 at Richmond, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.