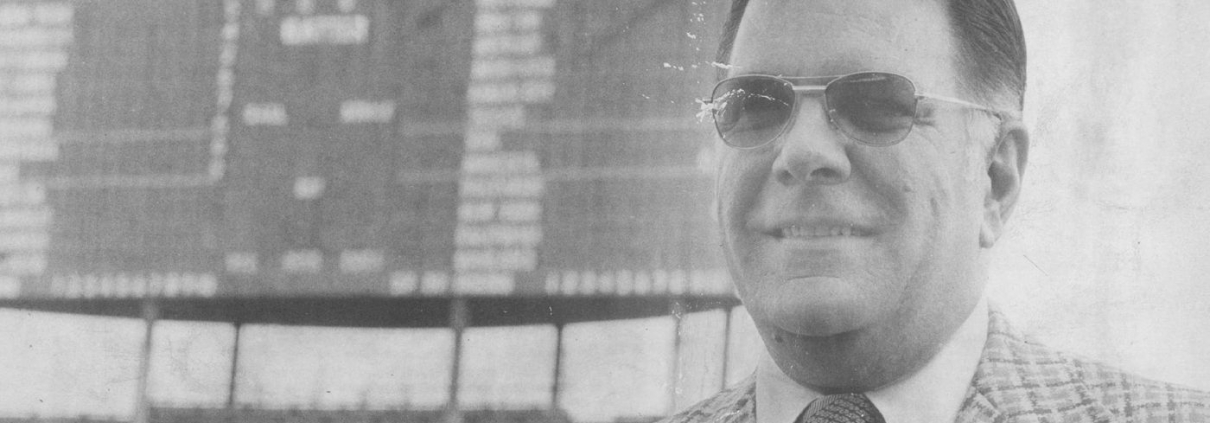

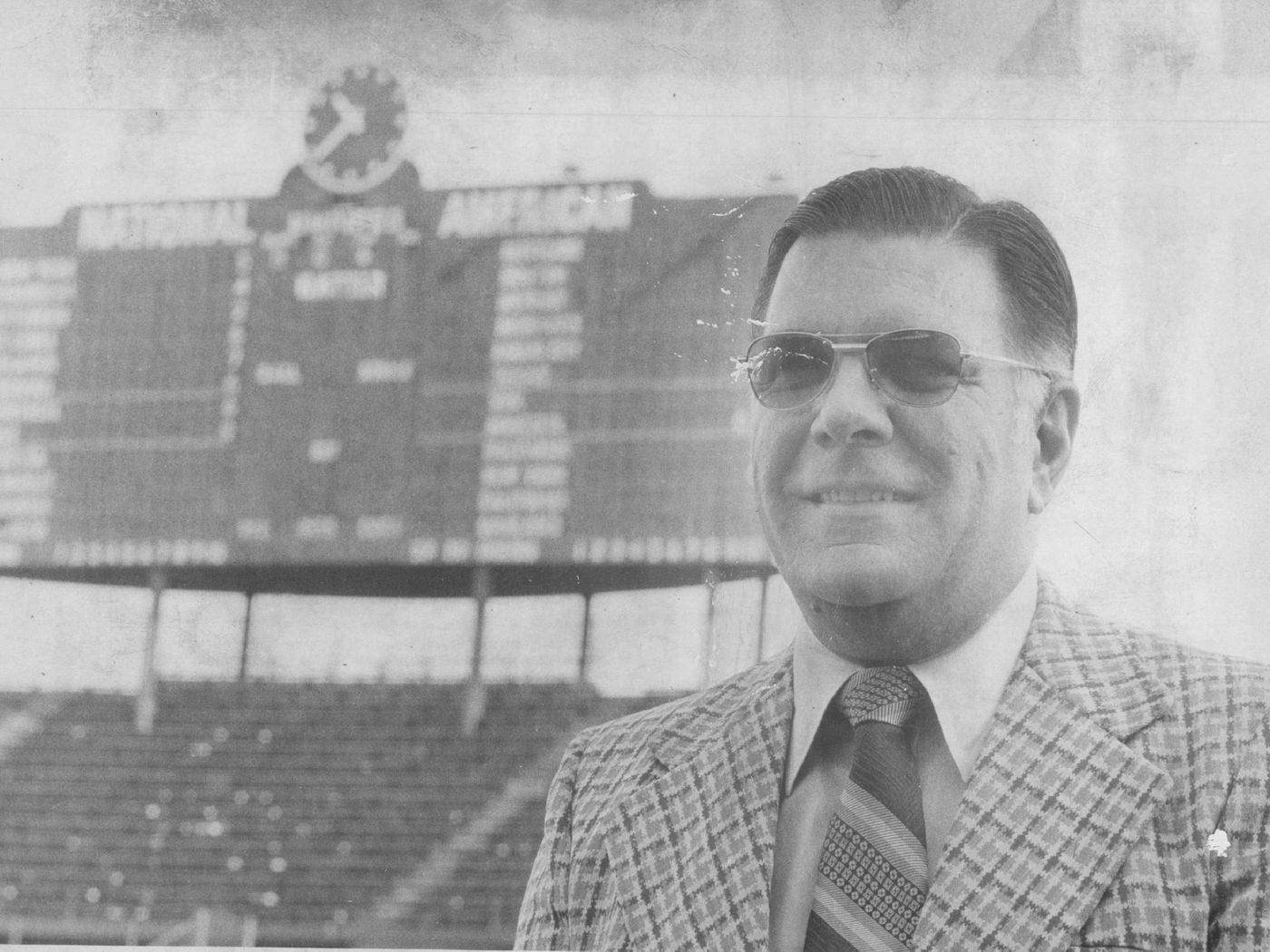

Salty Saltwell

Salty Saltwell was a baseball lifer — not between the lines on a baseball field but in the front office of the Chicago Cubs and four minor-league teams from 1950 to 2005. Along the way, he served as assistant general manager of the Sioux City (Iowa) Soos, executive secretary of the Western League, president and general manager of the Des Moines Bruins, concessions manager of the Los Angeles Angels in the Pacific Coast League, and general manager of the Fort Worth Cats in the Texas League. He then moved up to the Cubs’ front office, where he served in various capacities including GM from September 30, 1975, to November 24, 1976. Overall, he was a part of the Cubs’ organization for 50 years.

Looking back at his baseball career, Saltwell told Sioux City Journal sportswriter Terry Hersom in 2005, “My association with the [P.K.] Wrigley family was probably the biggest highlight. But there were so many.”1 P.K. Wrigley had assumed ownership of the Cubs in 1932 upon his father William Wrigley Jr.’s death and carried on until his death in 1977.

“I remember growing up at Wrigley Field,” said daughter Susan Saltwell in a telephone interview. “My mother was a huge baseball fan, and I am a huge Cubs fan. It was a little more of a job for my dad. I have pictures of my mother with my sister and I at the park (Wrigley Field) when I was about four years old. She loved it, and she started taking us down to the ballpark at a real early age. Sometimes when my dad would go into the office on Sunday, he would take my sister and I. We would play in the offices, which was a huge treat for us,” she added. “One of my favorite childhood memories is going down there in the winter with pristine snow on Wrigley Field and doing snow angels.”2

Eldred Ray “Salty” Saltwell was born on April 14, 1924, in Sioux City, one of two children of Charles and Amelia (Miller) Saltwell. The elder Saltwell was born on October 13, 1869, in Thiensville, Wisconsin, and moved to Manilla, Iowa, at age 19. He farmed around Manilla and Denison, Iowa, until 1924, when he moved his family to Sioux City and worked as a carpenter and construction engineer. His wife Amelia, who was born on June 15, 1872, in Garavillo, Iowa, was a homemaker. The couple also had a daughter, Minnie, born on May 23, 1897.

During the summers, Salty spent much of his time on the farms of relatives around Manilla. “One summer I rode my bicycle from Sioux City to Denison and visited relatives, then rode on to Manilla,” he recalled.3 He graduated from Sioux City East High School in 1942 and spent 39 months in the Army during World War II, reaching the rank of supply sergeant. After getting out of the service, he enrolled at Morningside College in Sioux City, setting the stage for his decades-long association with professional baseball.

After his sophomore year of college, Saltwell got a job as head usher for the Class-A Sioux City Soos, then a farm club of the New York Giants. The Soos captured the Western League regular season title that year with an 81-49 record, but lost to the Pueblo Dodgers four games to one in the playoff championship. In 1948, Saltwell provided telegraphic play-by-play descriptions of Soos’ games for transmission to home radio stations of visiting teams.

Saltwell helped establish Morningside College’s new sports public relations service, graduated in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree, and was put in charge of the players’ clubhouse at Soos Park that season. He also served as the team’s trainer. On February 4, 1950, Soos general manager Mike Murphy announced Saltwell’s appointment as assistant GM. “We’re very happy to have Salty as a member of the Soos’ family,” Murphy said. “His interest in the organization and his experience in various athletic fields make him the perfect man for the job.”4 The year ended on a sad note, however, as Saltwell’s father Charles died on December 23 at age 81 in a Sioux City hospital after a three-month illness.

Saltwell had an adventure with the forces of nature in 1953. On June 8, he and Sioux City owner Adam Pratt escaped a flash flood that left 15 feet of water on Soos Park in two hours.5 Both men left the ground-level office of the ballpark at 1 p.m. and headed for their cars. Taking a dirt road, Salty was caught in the swirling current and had to abandon his car. He managed to climb on a box car on a rail siding and was marooned for four hours before he was rescued. Meanwhile, Pratt drove down a railroad track to safety.6 The ballpark sustained an estimated $25,000 of damage, forcing cancellation of the team’s four-game series against Pueblo.

Later that same year, Saltwell’s career got a boost when he was appointed executive secretary of the Western League at age 29 while serving as the Soos’ business manager. League president Ed Johnson — then also a U.S. Senator from Colorado — made the announcement on December 3, 1953, in Atlanta, Georgia, the site of the minor leagues’ winter meetings. Under Saltwell’s watch, the Western League office operated from Sioux City rather than Colorado Springs, Colorado.

The Saltwell family suffered a loss when Salty’s mother died August 3, 1954, at a Sioux City hospital after a long illness stemming from a hip fracture six months earlier.

On January 18, 1955, Saltwell succeeded John Holland as the Des Moines Bruins’ president and general manager. Holland, who had been with the Bruins since 1947, became president of the Los Angeles Angels in the Pacific Coast League. Saltwell was introduced at a luncheon in Des Moines with manager Les Peden, new Cubs vice president Clarence “Pants” Rowland, and Cubs business manager Jim Gallagher.7

Less than a month later, after dating for nine years, he and Betty Ann Macur of Sioux City were married in the chapel of Methodist Hospital in Sioux City. They had met at Morningside College, where Betty graduated and worked in the college registrar’s office while Salty was in the service. Originally, the couple planned to be married in the home of her parents. However, Betty’s mother, Lillian Cairy, was recovering from surgery and was not strong enough to have the wedding at home.8 The couple eventually had two daughters, Cairy, born in 1957, and Susan, born in 1960. “He loved his girls,” daughter Susan recalled. “He would have custom made clothes for Easter for the three of us.”9

The location of the wedding was not the only unusual aspect of the milestone in Saltwell’s life. The Western League had a special meeting in the office of Ed Johnson (by then governor of Colorado) in Denver on Sunday, February 13. It led Salty to ask Johnson, “Do you think we can wind up the meeting in one day?”10 Assured that the meeting could wrap up on such a schedule, Saltwell flew from Sioux City to Omaha on Saturday afternoon, February 12, and took the night train to Denver. “All the time, he [Saltwell] was hoping the baseball meeting would end so he could get back to Sioux City in time for the wedding,” Des Moines Tribune columnist Gordon Gammack said.11 Gov. Johnson, who also was still the president of the Western League, lent his private limousine to Saltwell to cut through the Denver traffic just in time to catch a plane to Omaha. A friend met Salty in Omaha and drove him to Sioux City that Sunday night.

On February 25, 1955, Saltwell was appointed acting treasurer of the Western League. Ralph Winegardner of Wichita, Kansas, formerly a star minor league pitcher, replaced Salty as the league’s executive secretary. It did not take him long to get acclimated to his new position in Des Moines. In a talk at an Ad Club meeting on March 1, 1955, he expressed optimism about the new season despite the loss of Denver and Omaha to the American Association. “For the first time since the league was reactivated in 1947, every club has a complete working agreement with a major league organization,” he said. “That fact alone should assure close competition and I look forward to a balanced race.”12

The Des Moines Bruins’ ticket sales picked up when Pepper Martin replaced Peden as manager in early July. The Bruins were mired in fifth place with a 35-45 record when Saltwell turned to the Wild Horse of the Osage, well remembered as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals and their “Gas House Gang” throughout the 1930s. “The advance sale is one of the best we’ve had all year,” Salty said as the local club prepared to take on Lincoln in a doubleheader at Pioneer Memorial Stadium. “For one thing, I think the Bruins, under Pepper, will give the fans a livelier type of performance. He’ll take advantage of the potential speed on our club, I believe, and play a more daring brand of ball.”13

The managerial move paid dividends as Des Moines’ attendance more than doubled over the last 35 games. Although the Bruins drew 25,510 fewer fans overall than the previous year, they finished second in the league in attendance at 88,181. “I’ll bet our entire loss came in the first half of the season,” Saltwell said. “If we’d been drawing in May and June the way we did the last two months, we’d have finished ahead of ’54.”14

On January 9, 1957, the Cubs promoted Saltwell to concessions manager for the Los Angeles Angels of the PCL. “We hate to take Salty from Des Moines. He has done a fine job here,” said Holland, the Cubs’ front office head and former Des Moines GM. “But we have to have an experienced executive in L.A. The concessions operation there is a big and important one.”15

Saltwell’s stay in Los Angeles lasted less than a year, though. On November 5, 1957, he was named president and general manager of Fort Worth, the Cubs’ Texas League affiliate. As a result, he was reunited with the Cats’ new manager, Lou Klein, who had led Des Moines to a third-place finish in the Western League in 1956. Fort Worth Star-Telegram sports editor Bill Van Fleet described him as “an easy talker” and “personable. . . Saltwell … is a pleasant, crew cut, dark-haired young man who looks like he might have been a college fullback. However, he said he had not participated in any athletics at Morningside.” Saltwell explained, “I was too busy making money at various jobs from publicity man to making travel arrangements.”16

Some months later, Salty told Star-Telegram sportswriter John Morrison that spring training for him started in January when contracts were mailed to players. “I form an opinion of the players I don’t know by observing their handwriting. I’ve often thought of taking a course in graphology, then seeing how far I’ve missed on my first opinions of a player.”17

On April 12, 1958, Saltwell picked up added duties on the business side of the Cubs’ front office in Chicago while remaining as president of Fort Worth. Over the next 47 years under three different owners, he served in several capacities other than GM: concession manager, traveling secretary, assistant secretary-treasurer, secretary, vice president and consultant. He even served on the National League scheduling committee for many years.

As assistant secretary-treasurer, Saltwell oversaw concessions at any event at Wrigley Field, including the Chicago Bears’ home games until the Bears moved to Soldier Field in Chicago in 1971. In 1970, Saltwell told Des Moines Register columnist Maury White that Cubs fans consumed about three times as much food and drink per customer as Bears fans. “People don’t like to eat popcorn or peanuts while wearing gloves, and beer doesn’t sell in cold weather. Most of the football patrons have reserved seats and arrive late, cutting down on time spent in the park. Additionally, a football admission is about twice that for baseball, so people simply spend less on concessions.”18

At the time, the Cubs and Minnesota Twins were the only major league clubs to operate their own concessions. “We serve a 10-cent hotdog … 10 to a pound, same as you buy in a store … whereas many parks sell 12-15 to the pound,” Salty said. “We stock about 30 different foods or drinks and 60 souvenir items.”19 A year later, Saltwell had to explain that Wrigley did not increase the price of his chewing gum products such as Doublemint and Juicy Fruit to pay for the players’ salary increases. The price increase of Wrigley’s gum nearly coincided with GM John Holland’s announcement that the Cubs would have the biggest payroll in the major leagues. “I’ve had to write ─ or dictate ─all these letters explaining that the ball club is not a subsidiary of the gum company, that they are totally separate entities,” Saltwell said.20

In 1973, Salty became entwined in a controversy involving the organ music at Wrigley Field. “It’s terribly noisy. It interferes with our privacy,” said Blanche Vision, who lived in a 20th-floor apartment about a mile away along Lake Michigan. “I personally have gotten headaches on game days.” Her husband Philip added, “I’m a Cub fan. This puts me in a very precarious position,” Why, the organ music doesn’t bother me when I’m in the stands. But if the chimes of an ice cream truck were considered a nuisance, I’d say this organ is 10 times the nuisance.” He eventually went to Citizens Against Noise (CAN), which took the case to Wally Poston, head of the city Department of Environmental Control. CAN president Theodore Berland claimed that the music violated the city’s noise ordinance and asked Poston to check the decibel level at the beginning of the season. Saltwell characterized the couple’s complaint as “a little premature.” He explained, “We try to catch it and turn down the organ” when the breezes are toward Lake Michigan. He added that a new organ would be installed for the 1973 season. He also promised the Cubs would do what it could to placate the Visions and other Cub neighbors.21

Saltwell’s promotion to general manager on September 30, 1975, stunned most of the baseball world. The former vice president in charge of park operations replaced Holland, who continued to serve in an advisory capacity. When asked about why he rejected such candidates as Carroll “Whitey” Lockman and Blake Cullen, Wrigley said, “They were too close to the present management.” Holland praised the move, saying, “Salty is most qualified. He has had 25 years in all phases of baseball. He will be in charge of everything at the big league levels.” The Chicago Tribune’s Richard Dozer noted that Wrigley “has tried stranger things,” citing the experiment in the early ’60s with “athletic director” Bob Whitlow and the revolving “College of Coaches” instead of a manager.22

Wrigley’s surprising choice did not impress another Chicago Tribune staffer either. “It is well known that Saltwell, during his career with the Cubs, never let a hot dog spoil or lost a dugout. I don’t know about Salty being cast in the role of hardboiled general manager, unless Wrigley wants someone to get tough with beer vendors,” David Condon wrote in his column, In the Wake of the News. “But I guess anyone can be a general manager ─ the best the Cubs ever had were two former sportswriters, Bill Veeck Sr. and James T. Gallagher.”23

“To use an army term, I didn’t buck for the job,” Saltwell told the Chicago Daily News. “I was kind of surprised when John [Holland] came in Sunday on behalf of Mr. Wrigley and asked me if I would take it.”24

Saltwell’s daughter Susan said, “My father loved working for the Wrigley family. That was an immensely rewarding experience. I never heard that criticism from my dad [that Wrigley was more concerned about fans having an enjoyable experience at Wrigley Field than winning]. My dad was a company guy through and through. He never would have said anything negative about Mr. Wrigley. He always had the utmost respect for him.

“He used to tell me he was the go-between for P.K. and [P.K.’s] wife. Eventually that relationship extended to young Bill [Wrigley] and P.K. Working for the Wrigley family was the thrill of a lifetime for my dad. They rewarded loyalty. He used to go up to the [Wrigley] mansion in Lake Geneva for meetings and he’d come back sunburned because of his short-sleeve shirt. He said, ‘Yeah, we were on the boat all day.’ It was a great match. My dad was super, super loyal. Any salacious gossip about the ball players, I learned from somebody else. My father never would have betrayed that trust.”25

Saltwell’s first big move as GM was trading shortstop Don Kessinger to the St. Louis Cardinals for relief pitcher Mike Garman on October 28, 1975. The 33-year-old Kessinger had been with the Cubs since his debut on September 7, 1964, and had been a National League All-Star six times. Kessinger was the last holdover from the popular Cub teams of the late 1960s to early 1970s that included four eventual Hall of Famers: Ernie Banks, Billy Williams, Ferguson Jenkins, and Ron Santo.

On February 6, 1976, he signed 1975 NL batting champion Bill Madlock for a reported salary of $75,000 to $80,000. At the time, Madlock saw no need for an agent or a multi-year contract.26

Two months later he signed outfielder Rick Monday to a one-year contract in a trailer outside Scottsdale Stadium in Scottsdale, Arizona, that served as the Cubs’ spring training offices. “Mr. Saltwell has been very good to deal with,” Monday said. “I think he realized a lot of things that we have been trying to point out to him.”27

The condition of the team’s spring training facilities in Scottsdale was an issue during Saltwell’s short term as GM. Player Andre Thornton warned in late March 1976 that the team would not be ready for the new season.28 The stadium was the only place all the Cubs had for practice. The club’s minor leaguers were forced to work out at a high school complex a mile away. After training in Scottsdale since 1967, they moved to Mesa, Arizona, for spring training in 1979.

Saltwell expressed patience when the Cubs lost three straight games in April despite scoring 29 runs. That changed on May 17 when he traded Thornton to the Montreal Expos for pitcher Steve Renko and outfielder Larry Biittner, leading Chicago columnist Robert Markus to observe, “Others may accuse Salty Saltwell of pushing the panic button, but I can only applaud him for finally discovering what the darned thing is there for.”29

On June 8, 1976, Saltwell obtained pitcher Joe Coleman from the Detroit Tigers, and Coleman immediately became the club’s new player representative. “Apparently the Cubs got him without even [manager Jim] Marshall knowing general manager Salty Saltwell obtained him from Detroit and deposited him in the Cub locker room,” Chicago sportswriter Bob Verdi said. “Whether this indicates that Saltwell and Marshall do not communicate doesn’t matter; the players think they don’t, and that’s yet another crutch for them to brand this situation hopeless while acting accordingly.”30

As the 1976 season wound down in September, Saltwell was already looking ahead. “We still need a left-handed starting pitcher,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “Our shortstop position is still weak, and one of our weaknesses is a good power hitter. We had hoped Jerry Morales would improve his RBI production and do the job there.”31 The only left-handed pitcher on the impending list of 31 free agents was Baltimore’s Ross Grimsley. “We turned him down last winter,” Saltwell said.32

In October, Salty was surprised to learn that Madlock had hired agent Steve Greenberg, the son of Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg, to participate in negotiations that could lead to a multi-year contract worth $1 million. Madlock had just captured his second straight NL batting title. “He’s got to work on a few things yet,” Saltwell said. “A really outstanding superstar nowadays works to improve himself in so many ways. The people he [Madlock] likes to emulate, he doesn’t do yet. While Saltwell said he’d welcome an early meeting with the batting champion, he added, “But he’s not going to get any more with Greenberg representing him than if he represented himself, which he has done so well in the past.”33 Despite hitting .336 during his three seasons with the Cubs, Madlock was traded on February 11, 1977, to the San Francisco Giants for Bobby Murcer, Steve Ontiveros, and minor leaguer Andrew Muhlstock.

Salty’s status with the Cubs was up in the air in November when Wrigley expressed dismay at the Cubs’ operation and loss of $900,000 in the preceding season. “Saltwell’s understanding of what a general manager is and my understanding of what a general manager is haven’t jibed,” Wrigley said. “I’m not going into details on where I’ve been disappointed [with Saltwell]. But in the first place, I’ve discovered the bleachers are falling down. It will take close to a million dollars out there.”34

The uncertainty ended when the 81-year-old Wrigley replaced Salty with former player, manager, and executive Bob Kennedy as director of operations on November 24, 1976. Herman Franks replaced Marshall as manager. Saltwell’s responsibilities were cut to secretary and director of park operations. He served as a special assistant to the GM in his final three seasons with the team. He was inducted into the Greater Siouxland Athletic Association Hall of Fame in April 2005, the year of his retirement from baseball.

“I think he knew it [the GM job] wasn’t his strong point,” said Susan Saltwell. “Again, it was the whole loyalty thing. P.K. [Wrigley] gave him the position because he was loyal to his people — maybe to a fault. My dad had never played so he didn’t have the player perspective. Around that time, baseball was splitting off. You had the player end of it and the business end of it. He took it [the GM job] because his boss said, ‘This is something I want you to do.’ He wasn’t particularly devastated when they made the change the next year.”35

Susan also recounted that “if we were at the ballpark, he’d come out [of his office] and sit with us for an inning or two. Otherwise, for the most part, he was in his office, and he always had the game on TV. He was a huge fan, but he didn’t get emotional about baseball like my mother and I did. My parents, being from Sioux City, were very unpretentious, very unassuming. They were Iowa born and bred.”

Salty was 92 when the Cubs broke a drought of 108 years without a World Series championship in 2016. “He was the first person I called,” Susan said. “He did get a little weepy then. He was just like, ‘We finally did it!’”36

Saltwell’s wife, Betty, passed away on January 10, 2019, at her home in Park Ridge, Illinois. Her husband died at their home on May 3, 2020, at age 96. Besides their two daughters, survivors included four grandchildren and several nieces and nephews.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Don Zminda,

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author used baseball-reference.com, MLB.com, newspaperarchive.com, newspapers.com, StatsCrew.com, and whitepages.com.

Notes

1 Terry Hersom, “Sioux City’s Premier Cubs Fan: Saltwell,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, April 26, 2005: D1, D5.

2 Susan Saltwell, telephone interview.

3 Maury White, untitled column, Des Moines (Iowa) Register, August 8, 1972: 18.

4 “Saltwell Gets Post With Soos,” Sioux City Journal, February 5, 1950: 38.

5 “Pueblo Series Washed Out,” Sioux City Journal, June 9, 1953: 15.

6 “Flees For Lives,” Des Moines Register, June 14, 1953: 26.

7 Bill Bryson, “Saltwell, New Bruin Boss, And Cub Brass Here Today,” Des Moines Register, January 18, 1955: 14.

8 Gordon Gammack, untitled column, Des Moines Tribune, March 3, 1955: 1.

9 Susan Saltwell, telephone interview.

10 Bill Bryson, “Big Worry for Salty,” Des Moines Register, February 11, 1955: 18.

11 Gammack.

12 “Early Buyers To Get Extra Bruin Ticket,” Des Moines Register, March 2, 1955: 15.

13 Bill Bryson, “Bruins’ ‘Gashouse’ Era Begins,” Des Moines Register, July 9, 1955: 10.

14 Bill Bryson, “W.L. Attendance Up,” Des Moines Register, September 23, 1955: 18.

15 Bill Bryson, “Freeman, 28, Named General Manager of Bruins,” Des Moines Tribune, January 9, 1957: 18.

16 Bill Van Fleet, “Cats’ New President Steps on All Rungs,” Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram, November 7, 1957: 17.

17 John Morrison, “It’s Rapid Pace For Cat Prexy,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 30, 1958: 2I.

18 Maury White, untitled column, Des Moines Register, August 25, 1970: 17.

19 White.

20 Bill Bryson, untitled column, Des Moines Tribune, March 24, 1971: 16.

21 Bruce Ingersoll, “Cubs’ ‘Music’ Noise to Him,” Des Moines Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times, March 17, 1973: 10.

22 Dozer, “Saltwell new Cubs General Manager.”

23 David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, October 3, 1975: 56.

24 Armand Schneider, “Saltwell Ready for Challenge,” Des Moines Register and Chicago Daily News, October 5, 1975: 50.

25 Susan Saltwell, telephone interview.

26 Richard Dozer, “Cubs’ Madlock Shuns Multi-Year Pact,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1976: 43.

27 Richard Dozer, “Cubs sign Rick Monday to 1-year Contract,” Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1976: 170.

28 Richard Dozer, “Training Facilities Hurt Us: Thornton,” Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1976: 79.

29 Robert Markus, “Saltwell Panic a Step Forward,” Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1976: 69.

30 Bob Verdi, “Awful Truth is, Cubs are Truly Awful,” Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1976: 73.

31 Robert Markus, “Cubs’ ‘Next Year’ may be in Offing,” Chicago Tribune, September 6, 1976: 36.

32 Markus.

33 Joe Goddard, “Cubs’ Madlock Eyes $1 Million Package,” Des Moines Register and Chicago Sun-Times, October 6, 1976: 22.

34 Bob Pille, “Wrigley Unhappy with Cub Operation,” Des Moines Register and Chicago Sun-Times, November 6, 1976: 17.

35 Susan Saltwell, telephone interview.

36 Susan Saltwell.

Full Name

Eldred Ray Saltwell

Born

April 14, 1924 at Sioux City, IA (USA)

Died

May 3, 2020 at Park Ridge, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.