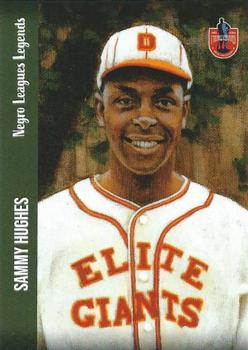

Sammy Hughes

Sammy Hughes’ name will almost certainly appear on any list of the top players of the Negro Leagues in the 1930s and 1940s. Hughes didn’t draw the attention of some of the bigger personalities of the day like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, but it is generally agreed that he was one of the most talented and well-rounded players in the leagues. Former stars Monte Irvin, Cool Papa Bell, and Buck Leonard were among several Negro League greats who listed Hughes as their top second baseman when asked to compile their personal all-time teams.1

Sammy Hughes’ name will almost certainly appear on any list of the top players of the Negro Leagues in the 1930s and 1940s. Hughes didn’t draw the attention of some of the bigger personalities of the day like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, but it is generally agreed that he was one of the most talented and well-rounded players in the leagues. Former stars Monte Irvin, Cool Papa Bell, and Buck Leonard were among several Negro League greats who listed Hughes as their top second baseman when asked to compile their personal all-time teams.1

The Seamheads.com database recorded Hughes’ career batting average in the Negro Leagues as .316, with a high of .372 in the 1939 title season. And though fielding statistics for Negro Leagues may not be absolute, what is available shows that Hughes was among the top fielders at second base year after year. He led the league in Range Factor/Game three times and finished in the top five in fielding percentage in five seasons. In the 2001 edition of his Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James described Hughes as “a smart player who did everything well” and compared him to Hall of Famers Barry Larkin and Ryne Sandberg.2

There is no question that Hughes was one of the top infielders of his time, and possibly the top second baseman. The question could instead be whether he should join his fellow Blackball stars in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

He preferred to keep a low profile and stay clear of some of the excitement that came from being a professional baseball player. Contemporary player and fellow second baseman Dick Seay recalled, “Hughes was a nice fellow. He wasn’t one of those drinking guys…I’d be in one of those taverns talking to the guys, but he’d stay in the hotel or go out and get his girl and go to her house.”3 That may be part of the reason he never garnered as much attention for the Hall of Fame as other stars of his generation.

Samuel Thomas Hughes was born October 20, 1910, in Louisville, Kentucky. He was the last of 12 children born to Susie Hughes (née Cowherd). There is some uncertainty as to the identity of Sammy’s father. On his player questionnaire sheet, he listed Henry Hughes as his father, and Henry and Susie had been married, but the 1910 U.S. Census has Susie, listed as a widow when she would have been expecting Sammy. It could be that Henry passed just before Sammy’s birth. The Hughes family resided in downtown Louisville, and after Henry’s death Susie supported them as a laundress and housekeeper.

Sammy went to school through the eighth grade, then presumably went to work in either the coal mines or tobacco fields, where he had older brothers working. Sammy found time to play baseball in the city, though; when he was 18, he was deemed good enough to join one of the top Black teams of the area, the Black Caps. As a sixteen-year-old in 1927, he had appeared in a team photo with one of the other top teams in the city, the Louisville White Sox, but it is uncertain whether he played in any of their games.

The Louisville Black Caps were members of the Southern Negro League in 1929 when Hughes played for them. Then in 1930 the team moved up to the Negro National League; thus, Hughes became a major-leaguer at the age of 19.4 Towards the end of the 1930 season the Black Caps were incorporated with the White Sox. The combined team kept the White Sox name for the 1931 season and kept Hughes on the roster.

Following the 1931 season, where he batted .337 in league games, Hughes was recruited to join the Washington, D.C. entry in Cum Posey’s new East-West League for 1932. He initially played second base for Louisville, but the team wanted to try another player there, so he was moved to first base. The Washington Pilots thus recruited Hughes as a first baseman; the keystone belonged to Frank Warfield, the Pilots’ manager and the heart of the team. In a sad turn of events, Warfield unexpectedly died in July after a hemorrhage, and Hughes inherited the regular second base role.

While playing in Washington, it was likely that Hughes was married. A 1932 article mentions Hughes temporarily leaving the Washington club to tend to his sick wife in Louisville.5 However, U.S. Census records from 1930 and 1940 do not indicate that he was married in those years.

In many of his pictures, Sammy can be seen with a grin on his face. Outside of giving umpires the occasional hard time, he was mild-mannered and possessed a friendly disposition — but if his grin didn’t help pinpoint him in a photo, then his height usually gave him away. Standing 6-feet-3, he was tall for about any position player in the league those days, let alone a second baseman. His stature not only helped him reach up to snag more line drives but also, when combined with his graceful footwork and mobility, increased his range and helped Hughes become one of the top defenders at the position. And Sammy T., as he was often called, was just as adept with his offense. He hit for high average and decent power, and his skills on the basepaths would later be considered equal to Jackie Robinson’s.6

The Pilots ceased operations after the 1932 season (and the East-West League dissolved soon after), leaving Hughes to look for a new team. Many of his former Louisville teammates, including Felton Snow, Poindexter Williams, and Willie Gisentaner, had joined the Nashville Elite Giants of the Negro National League, and Hughes reunited with them in Tennessee for the 1933 season. It was with the Elite Giants that the baseball world, including the white major leagues, started to recognize Hughes as a standout second baseman.

In August 1934 he was elected to play in his first East-West Classic, the Negro League equivalent of the then-recognized major leagues’ All-Star Game. He eventually was chosen for eight East-West games in his career (and played in six of them). But Hughes always considered his first appearance in the classic to be his favorite baseball moment.7

October 1934 marked Hughes’ first appearance in the California Winter League. Many baseball players in those days, Black and white, stayed busy nearly year-round playing in exhibition games and tournaments, winter leagues, semipro leagues, and barnstorming tours, and Hughes was no exception. The California Winter League was regarded as one of the prime showcases where Hughes and other Negro League players could first demonstrate their talents against competitive teams of white players. The Elite Giants owner, Tom Wilson, annually brought a team out to the league, and they could normally be found atop league standings, with Hughes often in a prominent role. Over his seven seasons in the league, he was consistently one of its top players, ranking fifth all-time in the circuit in career batting average (for a minimum 70 at-bats) and seventh overall in home runs.8

In 1935, Hughes followed the Elite Giants from Nashville to Columbus, Ohio (after a failed move to Detroit). He then returned to Washington D.C. when the team moved there in 1936. He played in the East-West Classic both years and was also selected to join in various all-star tournaments outside of the Negro National League.

Hughes participated in the highly advertised fall exhibition games in 1934 and 1935 played between teams led by Dizzy Dean and Satchel Paige. In August 1936, he had the opportunity to really put his talents on display on a national stage. Tom Wilson took his Elite Giants team, enhanced with select players from the rival Homestead Grays, and sent them out west to take part in the popular Denver Post Tournament for semipro teams not associated with Organized Baseball (the established major and minor leagues). The tourney was sometimes referred to as the “Little World Series of the West.” 9

The Negro League teams were not connected to Organized Baseball (not by their choice, of course). Thus, Wilson’s “National Negro All Stars” were eligible to take part in the event. The talent on the team was head and shoulders above the rest of the competition, and they dominated the field. Hughes hit .379 in the tournament as the All-Stars won all seven of their games and earned the cash prize of $5,000.10

Following that event, much of the team stayed intact and took part in an all-star tour formed by sports promoter Ray Doan. Among other things, Doan was known for his work with the traveling House of David team. Doan teamed up with Rogers Hornsby in October to stage a tour through Colorado and Iowa that would pit the team of Negro All-Stars against a team of stars from the major leagues.

A team highlighted by Hughes, Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, and Newt Allen took on a squad led by Hornsby that featured Johnny Mize, Harlond Clift, and Ival Goodman, among others. The Negro All-Stars won four out of the five games, much to Hornsby’s dismay.11 Hughes stood out among the all-stars, hitting .571 for the series, which topped Bell’s .421 and Charleston’s .364.

The only stretch when the Negro All-Stars seemed concerned was when 17-year-old Bob Feller started one game in his home state of Iowa and faced Paige for three innings. Feller was dominant, striking out eight of the 10 batters he faced over the three innings he pitched. (Paige just about matched Feller, striking out seven of 11). Hughes got the only hit off the teenage fireballer, an infield single that first baseman Mize fielded, but then Feller didn’t get to the bag fast enough to make the putout. After Feller left the game, the All-Stars’ bats came to life, and they won, 4-2.

By 1937 Hughes was generally recognized as one of the top players in the Negro Leagues. He was selected that year to play in his fourth consecutive East-West All-Star game, but he was one of many notable players who did not take part in the 1937 edition of the game. Several league stars, such as Paige and Gibson, also skipped it, instead joining a touring club assembled under the aegis of the Dominican Republic’s dictator, Rafael Trujillo.

Hughes did not join that team, but he was included among a group of players whose owners kept them out of the East-West Game in protest of how Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee managed the annual contest.12 Hughes instead joined a different team of all-stars that faced off against Paige and the “Dominican” team in a series of exhibition games.

He followed up the NNL season with an outstanding performance in the California Winter League, hitting .435 to help Wilson’s Philadelphia Royal Giants easily take the league pennant.

In December, Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey put out list of his All-Time All-Americans of the Negro Leagues in the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper and selected Hughes as his second baseman. That honor came one week after a column in the same paper opined how the Pittsburgh Pirates and just about any major league team could be improved by signing some of the top Negro League players, with Hughes specifically being mentioned.13

The Elites moved to Baltimore for the 1938 season, where they finally settled for good. Amid all the team’s moves, Hughes was a steady performer for the Giants. He was the only Giant selected to represent the team in the East-West Game from all four of the cities that it called home.

Hughes was the overwhelming leader in votes received for second base in 1938, makiing his fourth East-West classic. He again represented Baltimore in both games of a two-game all-star set in 1939.

The 1939 Baltimore Elite Giants, managed by Hughes’ longtime teammate Felton Snow, finished fourth in league standings but made the postseason when the league used a Shaughnessy playoff format that year.14 Hughes helped lead the way all season for the Giants with a .378 batting average and .500 slugging percentage.

After a surprising 3-1 series win over the Newark Eagles in the first round of the playoffs, Hughes and the Giants upset Josh Gibson and the powerful Homestead Grays to claim the Negro National League championship.

After the close of the 1939 season, Hughes made his only appearance in the Cuban Winter League. He started the season with Habana before joining Snow and Willie Wells with the Almendares team, but he did not fare well in Cuba. He hit an uncharacteristic .246 there (while teammate Wells won league MVP honors).15

The less-than-stellar performance by Hughes in Cuba didn’t slow him down; he had another solid year in 1940. His average dipped to .267, but he led the league in doubles with 13. In June, Hughes was again mentioned as a player who could contribute in the top all-white leagues. Baltimore Afro-American columnist Sam Lacy wrote that Hughes and other Black players “might bear watching” by AL and NL teams.16

Hughes was again the leading vote-getter at second base for the 1940 East-West game (and fifth in overall voting).17 However, he did not get to play in the showcase after being beaned in a game a week prior.

The 1940 season was the last chance that Hughes would have to play in the all-star event. He likely would have earned one more bid in 1941, but he left the Elite Giants and took an offer to jump to the Mexican League for the season. He joined several stars who played south of the border that year, including Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, and Willie Wells.

Hughes played much better with Algodoneros de Unión Laguna in Mexico than he did in Cuba, batting .324 in support of manager Martín Dihigo. He played only the one season in Mexico, then returned to the states in time for one more season in the California Winter League.

However, he played only two games in the CWL that winter, focusing instead on various exhibition games, including an October series in Los Angeles against several AL and NL players. Jimmie Foxx and Ted Williams were the headliners of that series, but “Slamming” Sammy Hughes was advertised in the Los Angeles Times as the top hitter for the Eastern Colored Giants.18 Hughes had two hits in the main game and scored two runs in a 9-6 loss to the white major-leaguers. While playing in the California Winter League and various exhibition tournaments in the state, Hughes must have taken a liking to Los Angeles – he made the city his home as early as 1940.19

Over the course of Hughes’ years in baseball, some momentum started building towards allowing Black players to integrate the white major leagues. Several players and managers from the AL and NL – such as Dizzy Dean, Johnny Vander Meer, and Bill McKechnie – came out in favor of Negro League players being accepted.20 At that time, though, no one team wanted to take the first step.

Lester Rodney, the sports editor for the Daily Worker, spearheaded a 1941 campaign titled “Can You Read , Judge Landis” that was directed to baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis, imploring the AL and NL to bring in Negro Leaguers. With white players being pulled into military service in World War II, there was no valid reason for talented Black ballplayers to still be kept from helping at least to fill out AL and NL rosters, or even hold starting jobs. Several other newspapers and a number of union organizations joined Rodney in the campaign to integrate the top white circuits. The pinnacle of the effort was an open letter to Landis penned by Rodney that was posted in the May 6 edition of the Daily Worker, demanding that the commissioner take action.

Following the bustle that Rodney’s letter stirred, and possibly as a result of it, the Pittsburgh Pirates looked like the team willing to make the move to integrate. Hughes was one of the players whom the Pirates invited to a tryout in 1942, along with one of his Baltimore teammates, rising star Roy Campanella, and New York Cubans pitcher Dave Barnhill. According to news releases, the tryout was initially set to take place on August 4, but after several weeks, the tryout had still not taken place. Some references claim the tryout was dropped with no official explanation from the Pirates.21 Yet it is also highly likely that the Pirates were never seriously considering a tryout and that the story was blown out of proportion by news media.

After the widespread news of the Pirates tryout, Hughes, Campanella, and Barnhill were invited to play with the Negro American League’s Cleveland Buckeyes for a single exhibition game in August. Teammates Hughes and Campanella requested permission from owner Wilson to play in the game, but with the Giants getting ready to face the rival Grays in the middle of a heated pennant race, the request was denied. Both players joined the Buckeyes anyway for $200 each (and maybe for a good cause — Campanella said the game was being played to raise funds for a ball field in Cleveland).22 Wilson then fined each man $250 for deserting the team and suspended them, denying both a chance to take part in that year’s East-West game.23 Both players soon returned to the Giants, but Campanella soon left and played out the year in Mexico, and the Elites finished in second place.

Heading into 1943, Hughes was 32 years old and would have been preparing for his 15th season in pro ball. He likely had a few good seasons left, but in January Hughes was drafted into the U.S. Army. He spent the next three years serving in the Pacific Theater.

Many professional ballplayers serving in the military during the war were assigned duties to be morale boosters and to play ball in front of troops around the world. Hughes, however, saw action as part of the 196th Support Battalion, notably taking part in an invasion task force in New Guinea.24

When the war ended, Hughes rejoined the Elite Giants for the 1946 season. By his own admission, he was no longer in playing shape. “I was heavy, I couldn’t move so well, and I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can get that weight off, get back into shape, and maybe not.’”25

Newspaper reports stated that Hughes held out from signing until June to get a better contract offer, but it was also possible that he was planning to retire until the Giants convinced him to come back and prepare his replacement. Baltimore was grooming young infielder Jim Gilliam to play second base alongside shortstop Pee Wee Butts but decided “Junior” wasn’t ready yet defensively.

The team worked with Gilliam, and Hughes especially helped guide him on his defense, until the day the veteran was ready to hand over the position. Hughes said, “I told Felton Snow, our manager, ‘Just let Gilliam and Butts, that combination, stay in there.’”26

The 1946 season, when Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in Organized Baseball, was Hughes’ last as a player.

Following his retirement, Hughes worked in the warehouse at a Pillsbury Mills plant in Los Angeles, then later as a janitor, coincidentally at the Hughes Aviation company. He remarried in 1956, to Thelma Novella Smith, and became a father to her daughter, Barbara. (In 1941, he married the former Mildred Dandridge, but according to census records they were divorced before 1950).

In 1972, Hughes was tracked down and interviewed by author John Holway for a piece that later appeared in Holway’s book, Black Giants. Holway noted that Hughes was very welcoming for the interview, but that he also chain-smoked throughout their meeting. During his career, Hughes had stayed clear of trouble with alcohol, unlike many of his past teammates, but for years he was indeed a heavy smoker. In 1981, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. Then, within months of the diagnosis, he suffered a fatal heart attack.27 He left behind his wife and stepdaughter.

Today, Hughes is buried in an unmarked grave next to two sisters, Bessie and Treacy, at Louisville Cemetery, located a few miles from where he was born and raised. In 2022, the Louisville chapter of SABR identified providing a grave marker for Hughes as a future project.

Nearly 25 years after Holway’s interview, Hughes’ career was given some well-deserved attention when he was listed on the final ballot for the 2006 Special Committee on Negro Leagues election to the Baseball Hall of Fame, but he was not selected. He was not on the Early Baseball Era ballot (which included both Negro Leaguers and white players) in 2021.

The years that Hughes lost to service in World War II likely hindered his case for election. Like so many players from his era, Hughes lost multiple years to the war that otherwise would have bolstered his career statistics. He came back to baseball just as Jackie Robinson was breaking the color barrier in the minor leagues, and Hughes himself was still being suggested as one of the top candidates to make the leap into Organized Baseball. But as was the case with other Black stars of his time, he was born just a few years too early, and integration arrived much too late.

When the Baseball Hall of Fame again considers Negro League players for enshrinement, one may hope that Hughes will be one of the names at the top of the list. As baseball researcher Gary Cieradkowski professed in his popular Infinite Baseball Card Set online series, “The biggest problem with the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown is that Sammy T. Hughes isn’t in it.”28

Last revised: October 8, 2022

Acknowledgments

Gary Cieradkowski sparked the idea for a Hughes bio during a discussion at the Pee Wee Reese Chapter SABR Day 2022 in Louisville.

The Louisville Public Library provided access to the digital archives of the Louisville Leader newspaper.

Statistics for Hughes in the Negro Leagues are taken from the Seamheads.com Negro League data base.

The Baseball Hall of Fame provided Hughes’ player questionnaire card from 1972.

This story was edited by Howard Rosenberg and Rory Costello and fact-checked by James Forr.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, Newspapers.com, Newspaperarchive.com, Ancestry.com, and Seamheads.com

Gay, Timothy M. Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York, Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Greenes, Steven R. Negro Leaguers and the Hall of Fame: The Case for Inducting 24 Overlooked Ballplayers (North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2020).

Holway, John B. Black Giants (Virginia, Lord Fairfax Press, 2010).

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, (Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1962, Expanded Edition, (Kansas City, Noir-Tech Research, 2020).

McNeil, William. The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2002).

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues (New York, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

Notes

1 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 480.

2 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 183.

3 John B. Holway, Black Giants, (Virginia: Lord Fairfax Press, 2010), 141.

4 The Negro National League was one of the leagues designated as a major league by MLB in December 2020.

5 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sports Spots”, Pittsburgh Courier, August 20, 1932: 14.

6 Timothy M. Gay, Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 145.

7 Holway, 142.

8 William McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 245.

9 Jason Hanson, “The Little World Series of the West”, History Colorado, https://www.historycolorado.org/story/2021/07/07/little-world-series-west.

10 W. Rollo Wilson, “National Sports Shots”, Pittsburgh Courier, August 22, 1936: 14.

11 Gay, 166.

12 Russ J. Cowans, “Easter Star Out of All-Star Game”, Detroit Tribune, August 7, 1937: 7.

13 “Challenge Hurled at Pittsburgh Pirates on Sepia Players Issue”, Pittsburgh Courier, December 11, 1937: 17.

14 Baseball-Reference.com shows that the Toledo Crawfords finished with the fourth best record in the league, but the team had switched to the Negro American League prior to the end of the season.

15 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: 1878-1961 (North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2007), 378.

16 Sam Lacy, “Looking ‘Em Over”, Baltimore Afro-American, June 1, 1940: 21.

17 Lester, 152.

18 “Ted Williams Heads All-Stars in Tussle”, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 1941: 25.

19 Hughes’ listed a home address in Los Angeles on his World War 2 draft card, dated October 16, 1940.

20 Larry Lester, “Can You Read, Judge Landis?”, SABR Journal Articles, https://sabr.org/journal/article/can-you-read-judge-landis/.

21 Larry Lester, “Can You Read, Judge Landis?”

22 Campanella, Roy. It’s Good to Be Alive, (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 89.

23 “Campanella, Hughes Cited for Fine, Suspension”, Baltimore Afro-American, August 15, 1942, 26.

24 “Negro Leagues Players Played Major Role In World War II”, Negro Leagues Players Played Major Role In World War II | by MLB.com/blogs | Monarchs to Grays to Crawfords (mlblogs.com)

25 Holway, 144.

26 Holway, 144.

27 Hughes’ death certificate provided by the State of California Department of Public Health.

28 Gary Cieradkowski, “Sammy T. Hughes: The Problem with the Hall of Fame”, StudioGaryC.com, https://studiogaryc.com/2020/12/20/sammy-t-hughes.

Full Name

Samuel Thomas Hughes

Born

October 20, 1910 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

August 9, 1981 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.