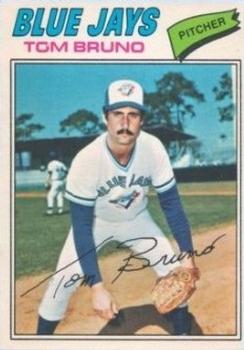

Tom Bruno

Tom Bruno pitched in parts of four major-league seasons from 1976 through 1979. A 6-foot-5 righty, Bruno mainly worked in relief, compiling a 7-7 record and a 4.22 ERA over 69 games. He signed with the Kansas City Royals in 1971 and attended that club’s pioneering Baseball Academy. After reaching the majors with the Royals in 1976, Bruno was a member of the inaugural Toronto Blue Jays in 1977. He displayed his best big-league form during the 1978 season after joining the St. Louis Cardinals. Shoulder problems set him back in 1979, though, and his career ended upon being released on March 31, 1980.

Tom Bruno pitched in parts of four major-league seasons from 1976 through 1979. A 6-foot-5 righty, Bruno mainly worked in relief, compiling a 7-7 record and a 4.22 ERA over 69 games. He signed with the Kansas City Royals in 1971 and attended that club’s pioneering Baseball Academy. After reaching the majors with the Royals in 1976, Bruno was a member of the inaugural Toronto Blue Jays in 1977. He displayed his best big-league form during the 1978 season after joining the St. Louis Cardinals. Shoulder problems set him back in 1979, though, and his career ended upon being released on March 31, 1980.

As it developed, Bruno was a day shy of qualifying for pension and associated benefits. At the time, this issue was far from his mind. Yet decades later, he still seeks to heighten awareness of inequity for the roughly 600 pre-1980, non-vested major-leaguers who remain.

Born on January 26, 1953, in Chicago, Illinois, Bruno says he won the lottery at six months old when he was adopted by Tony and Jackie (Schinker) Bruno. “People ask, ‘Aren’t you wondering about your real parents?’ I’m not. They (Tony and Jackie) are my parents. I just didn’t happen. They had a choice, and they chose me.”1 Tom’s birth father was killed in action in Korea before he was born. His birth mother was unable to care for a child and gave the infant up for adoption. The agency at the time had over 100 babies. Tony and Jackie chose Tom and later a daughter, Laura Ann.

Tony Bruno, who had Croatian ancestry, was an only child raised in Argo, Illinois. He was an electrical engineer with Page Engineering, a company that made dragline excavators, heavy mining equipment, for Peabody Coal. Jackie Bruno was born in Rib Lake, Wisconsin. She attended Georgetown University, then became a Navy WAVE and an emergency room nurse. The Brunos were devout Catholics who stressed the importance of education and were very supportive of their children. Bruno’s maternal grandfather, Martin Schinker, was the son of German immigrants, seeded Tom’s love of the outdoors. Schinker worked as a logger with the Civilian Conservation Corps and had settled in Rib Lake. It was there and in Dwight, Illinois that Schinker taught Tom how to hunt rabbits and pheasants and to fish. Tom would prefer the outdoors – baseball, fishing, and hunting – to the classroom.

Tom was raised in Downers Grove, Illinois, a western suburb of Chicago. In the late 1950s and 1960s, it still had a smattering of farms as well as a commuter railroad station. He quickly fell in love with baseball; as a third grader at Saint Joseph Catholic School, he stated his desire to play in the major leagues. “That’s all I ever wanted to be – a baseball player,” Bruno said. “Most kids change every week. One week they’ll want to be a policeman, the next a fireman, but not me.”2

Tom started organized baseball with Downers Grove Little League. He gained a reputation for throwing fearsome fastballs. Paul Carey, an opponent, was beaned by a Bruno fastball and even with helmet on was knocked unconscious. When Carey came to, his father and Bruno were standing over him. Carey said he did not know who looked more worried, his father or Bruno. He popped back up and the game continued. No one wanted to bat against Bruno.3

Outside of Tom’s supportive parents, Angelo and Randy Poffo also helped him develop as a young ballplayer. Angelo Poffo was a professional wrestler, physical education teacher, and world record holder for sit-ups.4 He built a batting cage in the driveway of the Poffo home. Randy, Angelo’s son, was Tom’s boyhood friend and constant teammate. Both Tom and Randy would play professional baseball. Randy attended an open tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals and was the only player signed. He played four minor-league seasons before a shoulder injury brought his release.5 Randy later joined the Poffo family business of professional wrestling. He donned the persona of Randy “Macho Man” Savage and became a superstar.

Bruno progressed through organized youth baseball (Little League, PONY, and Babe Ruth leagues). He played football and basketball too. His size and athleticism got notice from the coaches at Fenwick High School in Oak Park, Illinois, run by the Dominican Friars, 15 miles from the Bruno home. Tom was on scholarship and worked cleaning the athletic department after school and before practice. He described himself as a fair student at best, not because of ability, but simply owing to other interests. He played football for his first two years and even saw time on the varsity as a sophomore – an unusual feat at this school, where the football program dominated. After an injury, Bruno turned in his pads, which did not sit well with the football coaches. He never wavered about wanting to be a major-leaguer and football was getting in the way. He did continue to play basketball as well as baseball for all four years.

Bob Atwood, Fenwick’s first full-time baseball coach, was a former minor-leaguer and summer scout for the New York Mets.6 A teacher and cafeteria manager, Atwood was a soft-spoken man who would use phrases such as, “We blew out the candle,” to describe a season-ending loss.7 He loved Bruno’s talent and determination but not always his jocular attitude. The Fenwick Friars baseball team at the time did not have a dedicated ballfield. This squad of “orphans” took part in the competitive Chicago Catholic League (CCL). Bruno excelled as a pitcher, regularly throwing complete games even into extra innings.8 After his senior season, he earned the start for the CCL North versus the CCL South in the conference all-star game held at Comiskey Park, known as White Sox Park in 1971. He pitched well, though the CCL North squad lost 9-8 in 11 innings.9

It was expected that Bruno would be selected in the 1971 major-league amateur draft. That call never came. Disappointed, he looked for options to continue his dream of playing pro ball. Regardless of the amateur draft, his arm was in demand. Bruno played on multiple teams, including a club that represented Illinois in the Senior Babe Ruth Central Sectional tournament in 1970 and 1971. Bruno pitched for the Little Village Saints in the Connie Mack league as well.10

The University of Tulsa recruited Bruno to play baseball. The Golden Hurricane squad, led by Gene Shell, had just made an exciting run to the finals of the College World Series with future major-leaguers Steve Rogers, Jerry Tabb, and Steve Bowling. Tom and his father traveled to Tulsa on a recruiting trip.

Finally, the Kansas City Royals were holding open tryouts for their Baseball Academy, the brainchild of Royals owner Ewing Kauffman.11 In search of a competitive advantage, aiming to apply innovation to baseball as Kauffman did in his pharmaceutical business, the academy recruited undrafted ballplayers and other athletes. Kansas City scout Art Stewart ran the Midwest tryouts, and Bruno caught his eye.12 As noted, Tony Bruno believed in education. The Baseball Academy would allow Tom to play professional baseball and go to school at Manatee Junior College during the season with other academy players and attend Eastern Illinois University in the off-season.13

Thus, he signed with the Royals as an amateur free agent on August 21, 1971. The Baseball Academy program was regimented. Junior college in the morning and baseball in the afternoon. No television, no family.14 Bruno often slept in the locker room because smoking was not allowed in the dormitory. The academy was visionary and exposed players to coaches and guest lecturers. Hitting coach Charley Lau used video to develop his hitting philosophies at the Academy. Wes Santee, the record-setting Kansas track star, helped players with running technique. Ted Williams visited to discuss hitting.15 The team, also known as the Sarasota Royals, developed from playing junior college to major college and semipro teams to the rookie level Gulf Coast League. It finished atop league standings in both 1971 and 1972. Bruno and Frank White were top prospects at the academy.16

Yet even though the Baseball Academy broke professional baseball norms of the day, few players advanced to the high minors or made the major leagues. U.L. Washington made the majors while Ron Washington developed into a utility infielder and later a successful big-league coach and manager. The academy closed in 1974.

Bruno’s fearsome fastball played well in the Gulf Coast League. He struck out over a batter per inning and was promoted to Waterloo in the Midwest League (Class A). On August 23, 1971, he threw a seven-inning no-hitter with ten strikeouts.17 Bruno became fast friends with Dennis Leonard over a shared love of the outdoors. After the season, he enrolled at Eastern Illinois University.

By 1973, Bruno was with the San Jose Bees in the High-A California League. Pitching duties were a mix of 13 starts and 29 relief appearances, particularly in high leverage situations. He compiled a 13-8 won-lost record with 5 saves while recording 121 strikeouts in 137 innings. The years 1974 and 1975 were both split between Jacksonville of the Southern League (Class AA) and Omaha of the American Association (Class AAA). During this time, Bruno became primarily a starter with an increasing workload. On July 5, 1974, he threw his second minor-league seven-inning no-hitter for Jacksonville. “During my warm-up, I felt that I had my best stuff and that carried through. [Manager] Billy Gardner had confidence in me and I really enjoyed playing for Billy,” Bruno said.18

Bruno played winter ball in Puerto Rico for a working vacation. He led La Liga de Béisbol Profesional de Puerto Rico in ERA in 1975-76 with the Arecibo Lobos. The next season, he was traded to the Santurce Cangrejeros. Bruno said he would have been a 15- to 20-game winner in the majors if he had thrown the same way there as he did in Puerto Rico. “Hiram Cuevas was the GM, and I’ll tell you what: If you were doing OK, he was nice to you. If not, bye-bye,” said. Bruno.19 St. Louis Cardinals coach and fellow Chicagoan Jack Krol managed Santurce in 1977-78. They got along well, and Bruno enjoyed playing for Krol.

After an impressive 1976 spring training, Bruno started in Omaha once again. He compiled a 9-4 record and earned a promotion to Kansas City on July 29. “He’ll go to the bullpen. We need another right-hander out there with Mark Littell. We can use Bruno for long or middle relief,” said manager Whitey Herzog.20 “Billy Gardner told me that I was getting the call to Kansas City,” Bruno recalled. “Just awestruck walking into Kauffman Stadium for the first time. It was really a dream come true.”21 His friend Dennis Leonard was already there, along with George Brett, Marty Pattin, Steve Mingori, and others from the Royals system.

Bruno made his debut in long relief on August 1, 1976, in a Sunday game versus the Texas Rangers. He got a groundout from Danny Thompson, gave up a single to Juan Beniquez, and struck out Jim Sundberg.

Bruno picked up his first win in Boston at Fenway Park in two innings of work on August 26. He made 12 appearances that season. Outside of one performance on September 10 versus the hot-hitting Minnesota Twins – the 18-3 loss was the worst in Royals history at the time – Bruno’s debut season in the majors was solid. No Royals pitcher had much success that night: the team gave up 18 hits, 14 walks and two errors. “None of us could get anybody out. I threw a ball to Dan Ford and it is still in the air someplace,” said Bruno. That game proved to be an outlier for Bruno and the Royals, who went on to win their first American League West title. Disappointed at not making the postseason roster, Bruno went home back to Illinois for the offseason.

On November 5, 1976, Bruno was selected in the expansion draft by the Blue Jays. “It should have been a new opportunity, but it did not pan out very well in Toronto.”22 He started the year in AAA. The Blue Jays built out their minor-league system with a working agreement to place players with Toledo, then a Cleveland affiliate. Bruno was called up on May 6 but had to wait be until May 14 for his first appearance. Subsequent action was limited and all in relief. “I made the mistake of going into his [manager Roy] Hartsfield’s office and asking him if I could start a game. They had lost 70-some games. He thought I was trying to manage or something. I sat there about four months and only pitched in 12 ball games. He told me I ought to take another job.”23

In spring training 1978, Blue Jays pitching coach Bob Miller had nothing but praise, yet Bruno was not convinced that he had a future with the team.24 “I am throwing good on the side, but not getting into many games. I called Jack Krol and told him I thought I was not going to make it,” he said.25 Three days later, Bruno was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for Rick Bosetti. He split 1978 between AAA Springfield and St. Louis.

Bruno was called up to St. Louis on August 5. “I was surprised they called me up because my record was 5-9 at Springfield,” he said.26 A few hours later, he earned his first National League victory, helping to end a seven-game losing streak. On August 8, Bruno made his first major-league start in the second game of a doubleheader. He handcuffed the Philadelphia Phillies with a deceptive curve ball over seven innings in a 6-2 win. On August 11, he earned his first save by striking out the side in the 12th inning.27 Thus, in the span of seven days, Bruno compiled a 2-0 record with one save. He also singled in his first major-league at bat. “That was off Dwight Bernard. He hit my bat,” Bruno recalled.28

Bruno had a great rapport with manager Ken Boyer and was well regarded by pitching coach Claude Osteen.29 The 1978 season proved to be Bruno’s best in the majors. He appeared in 18 games with three starts, posting a 4-3 record with a 1.99 ERA. St. Louis beat writer Rick Hummel noted, “Bruno excelled in short relief, he excelled in long relief, and he excelled as a spot starter. Too bad he didn’t arrive sooner.”30 That season Bruno felt like there were “glimmers of capability.”31

Bruno made the big club out of spring training in 1979 and was slotted for relief. His primary batterymate in St. Louis, Hall of Fame catcher Ted Simmons, said of Bruno, “He doesn’t smile much. He doesn’t kid much. He is very serious about his work.”32 Bruno enjoyed the relationship with Simmons.

On April 10 versus the Cubs at home, Bruno entered the game after a 53-minute rain delay to pitch two innings for his first appearance. On April 18 at Wrigley Field, Bruno earned the win by pitching the 13th and 14th innings. His father Tony – a die-hard Cub fan – was razzed by friends about whom he would root for, the Cubs or his son.

Bruno stayed with the big-league club through June 25, making 25 appearances. Shoulder problems which hampered his performance sent him to the disabled list, then AAA Springfield until September. “Based on what Bruno did last year, there wasn’t any reason to believe he’d flounder like he did,” said Ken Boyer.33 During his stint at Springfield, he made 10 starts but struggled to find consistent success, compiling a 3-6 record. Back in St. Louis, Bruno pitched in just two more games. Cortisone shots became routine to treat his ailing shoulder.

Entering 1980 spring training, Bruno had a signed contract but was out of options.34 He had to either make the club or be released. Talk of work stoppage rumbled through clubhouses across baseball beginning in February. Bruno was ineffective and quipped in frustration, “I’ve got a better chance to make the Anchorage staff.”35 The players went on strike, which canceled the final eight days of spring training in late March.

Furthermore, Whitey Herzog, who was never keen on Bruno’s abilities, was serving as an unpaid consultant to Cards GM John Claiborne, offering opinions on players when Claiborne asked.36 (Herzog replaced Boyer as skipper that June and added the GM role later that summer.) That was the writing on the wall. Bruno was cut on March 31, the last day of spring training. He never returned to the mound at any level.

“When I got to the big leagues,” he recalled, “I wanted to be there so bad that I ‘over-tried.’ I know that it sounds crazy, but you can (try) too hard and it becomes a negative impact on your physical performance. I pushed myself too hard now that I look back at it. That is the main reason I did not have as much success as I would have like to have had.”37 He added, “Never had a great rapport with Whitey Herzog. He has always been known as a great manager and a player’s manager. Wish I would have had a better rapport, but really respected him as a manager.”38

There was one last baseball call, however. “Jack McKeon, general manager of the San Diego Padres, called in the end of August, to play AAA ball for San Diego. I wasn’t prepared at the time, so I said no. Then I never got another chance to play,” said Bruno.39

Bruno’s other great love then came into play: the outdoors. While baseball was ending, his next career was beginning. He trained and ran hunting guide dogs, including English pointers that quickly gained a reputation in the field. Bruno sold dogs to other hunters. One client ran a hunting lodge in Tamaulipas, Mexico and invited him to train the guides to handle the dogs. That became a job training dogs and guiding quail hunts and fishing outings. After a few years, Bruno made his way to Denver and the Professional Walleye Trail. He fished competitively for several years.

Bruno first married in 1983 and the couple adopted a son, Trevor Martin Bruno, in 1989. They divorced in 1992. The marriage did introduce Tom to South Dakota and its central location on the walleye circuit. He fished the crystal-clear waters of Lake Oahe, a large reservoir on the Missouri River, and relocated to Pierre, South Dakota in 1992. Bruno then started his guide and outfitting service, Major League Adventures. Offerings include fishing during the spring and summer and pheasant hunts on private land in the fall and winter.

“After I got out of baseball, I came up here and decided this is where I wanted to be. I’ve never regretted it,” said Bruno.40 Tom met his second wife, Jayne, at the Royals’ home opener in 2009. “We happened to be at the same place, same time, started talking, there was also an alumni golf tournament…we talked again and realized that we had grown up in Illinois about 60 miles apart,” Jayne said. “Tom was in the Chicago area, I was in more of a rural area. We’d also gone to the same university, Eastern Illinois University, only at different times,” she also noted.41

Tom Bruno’s significance to baseball goes beyond his four partial seasons in the majors. When he was released on March 31, 1980, the vesting requirement to earn a Major League Baseball pension was four full years of service time. As a result of the threatened players strike in 1980, the requirements changed.

The new and current requirements from the 1980 agreement, promulgated shortly after Bruno’s release, lowered service time to one day for health benefits and 43 days to be eligible for retirement allowance. The agreement was not retroactive for players whose careers finished from 1947 through 1979. Had he spent even one day on a big-league roster from April 1, 1980 onward, he would have qualified.

At the time, this decision affected over 1,100 former major leaguers. As of 2021, there were just over 600 remaining.42 A number of these players who are without pension and medical benefits from baseball participated in the strike of 1972 and the spring training strike of 1980. Those actions led to increases in pension and benefits with lower service time requirements.43 By any measure, these former ballplayers have demonstrated a legacy and responsibility built on equity, loyalty and fair play – a statement that can be found on the Major League Baseball Players Association website.44 “I don’t think it was a planned situation where those guys prior to ’80 were forgotten, but it was such a tumultuous time,” said Bruno. “it was kind of an accident, in my opinion, that we weren’t grandfathered in like everybody else.”

Over the years, these left-out former ballplayers, including Bruno, raised the issue. In 2011, a stipend package deal was put in place, providing an average yearly pre-tax payment of $3,800 per player but no health benefits.45 Regarding the double standard, Bruno believes, “Whatever we accrued, that should be the same for everybody.” He also does not place blame for this situation on today’s baseball player. “They’re busy trying to keep their own jobs,” Bruno said.46 He knows the difficulty of keeping a major-league spot firsthand.

Through the ups and downs from the Royals Academy, the success in the minors and Puerto Rico, the glimmers at the top level, and ending on the last day of 1980 spring training, Tom Bruno’s baseball career featured both bad and good. He showed resilience in transitioning to his second career in the outdoors. In retrospect, he stated, “I am a real lucky guy. All my life I have been able to do what I have a passion for.”47

Last revised: January 20, 2022

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Tom Bruno for his input.

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, baseballalmanac.com and LA84 Foundation Digital Library Collections.

The author attended Tom Bruno’s alma mater, Fenwick High School, and once asked Coach Bob Atwood if any Fenwick Friars made the major leagues. He answered in his soft respectful tone, “Tom Bruno.”

Notes

1 Rick Hummel, “Bruno’s top priority is to do his best,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1979: 37.

2 Bruno telephone interview with author, March 26, 2021. (Hereafter Bruno telephone interview.).

3 Paul Carey, email correspondence with Tom Bruno, May 7, 2021.

4 Angelo Poffo Death, https://wrestlerdeaths.com/angelo-poffo-death

5 Jeff Pearlman, “Randy (Macho Man) Savage’s dream was to make it to the Majors,” Sports Illustrated, May 23, 2011, https://www.si.com/more-sports/2011/05/23/macho-man

6 Robert Atwood Sporting News Contract Card, https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/14130/rec/6

7 “Friars’ finish unhappy,” Oak Leaves (Oak Park, Illinois), June 2, 1971: 59.

8 “Friars get pitching, hitting, defense but win just three: Loyola spoils it,” Oak Leaves, April 21, 1971: 66.

9 “South section Catholic Stars edge North section 9-8,” Suburbanite Economist (Chicago, Illinois), June 9, 1971: 38.

10 “Mack, Musial titles will probably remain south,” Suburbanite Economist, June 21, 1971: 68.

11 William Leggett, “School’s in: watch out for baseball players,” Sports Illustrated, August 23, 1971, https://vault.si.com/vault/1971/08/23/schools-in-watch-out-for-baseball-players

12 Royals Hall of Fame, Art Stewart, https://www.mlb.com/royals/hall-of-fame/members/art-stewart

13 “Kansas City tryout camp at Niles West, Daily Herald (Chicago, Illinois), June 15, 1972: 19.

14 Hal Bock, “Single swingers…,” Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, Illinois), October 14, 1980: 16.

15 Sam Mellinger, “Forty years later, Royals Academy lives on in memories,” Kansas City Star, August 2, 2014, https://www.kansascity.com/sports/spt-columns-blogs/sam-mellinger/article940797.html

16 Joe McGuff, “Sporting Comment,” Kansas City Star, July 19, 1972: 36.

17 “No-Hitter for Waterloo’s Tom Bruno,” Decatur Daily Review (Decatur, Illinois), August 24, 1971: 14.

18 Clubhouse Conversation podcast, Tom Bruno, https://clubhouseconversation.com/2014/12/tom-bruno/, December 2014. (Hereafter, Clubhouse Conversation podcast.)

19 Thomas E. Van Hyning. Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 48.

20 Sid Bordman, “Royals gird for Rangers,” Kansas City Star, July 30, 1976: 33.

21 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

22 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

23 Gordon Edes, “Road to the majors is nearby,” Chicago Tribune, August 12, 1978: 76

24 Ross Hopkins, “Jays pitcher helping own cause,” Ottawa Citizen, March 14, 1978: 17

25 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

26 Neal Russo, Cards Clip Mets, End 7-Game Skid, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 6, 1978, p: 93.

27 Rick Hummel, “Cards Win Dramatic Ho-Hummer,” Post-Dispatch, August 12, 1978, p: 5.

28 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

29 Prospects, Post-Dispatch, April 2, 1978: 18K.

30 Rick Hummel, “Final Grades Indicative of Cards’ Woeful Year,” Post-Dispatch, October 2, 1978: 32.

31 Bruno telephone interview.

32 Rick Hummel, “Bruno’s top priority is to do his best,” Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1979: 37.

33 Rick Hummel, “A close call for Cardinals: Yanks nearly got Fulgham,” Post-Dispatch, August 28, 1979: 9.

34 Rick Hummel, “Kennedy Oks bench but not a return to minor leagues,” Post-Dispatch, March 3, 1980: 16.

35 “Redbird notes,” Post-Dispatch, March 16, 1980: 39.

36 “Why Cardinals wanted Whitey Herzog in, Ken Boyer out,” Retrosimba.com, June 8, 2020.

37 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

38 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

39 Clubhouse Conversation podcast.

40 Brent Frazee, “Making the most of life’s changups,” Kansas City Star, September 16, 2012: B14.

41 Michael Woodel, “Though without MLB pension, Bruno relishes post-baseball life in Sully County,” Capital Journal (Pierre, South Dakota), September 18, 2021, https://www.capjournal.com/news/though-without-mlb-pension-bruno-relishes-post-baseball-life-in-sully-county/article_2e56a630-f927-11eb-959e-0b02b298ff17.html.

42 Madden.

43 Bill Madden, “MLBPA has another chance to right a wrong that dates back to 1980,” New York Daily News, November 6, 2021, https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/ny-mlb-cba-negotiations-right-a-wrong-20211106-vloym33ojjfxnkzij6qma7b4xm-story.html.

44 Major League Baseball Players.com, https://www.mlbplayers.com/history

45 Douglas J. Gladstone. A Bitter Cup of Coffee (Tarentum, Pennsylvania: Word Association Publishers, 2010).

46 Woodel.

47 Bruno telephone interview.

Full Name

Thomas Michael Bruno

Born

January 26, 1953 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.