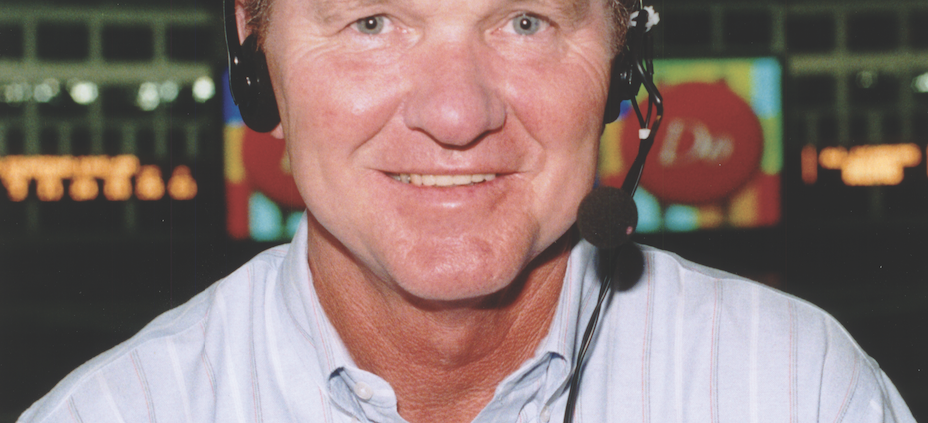

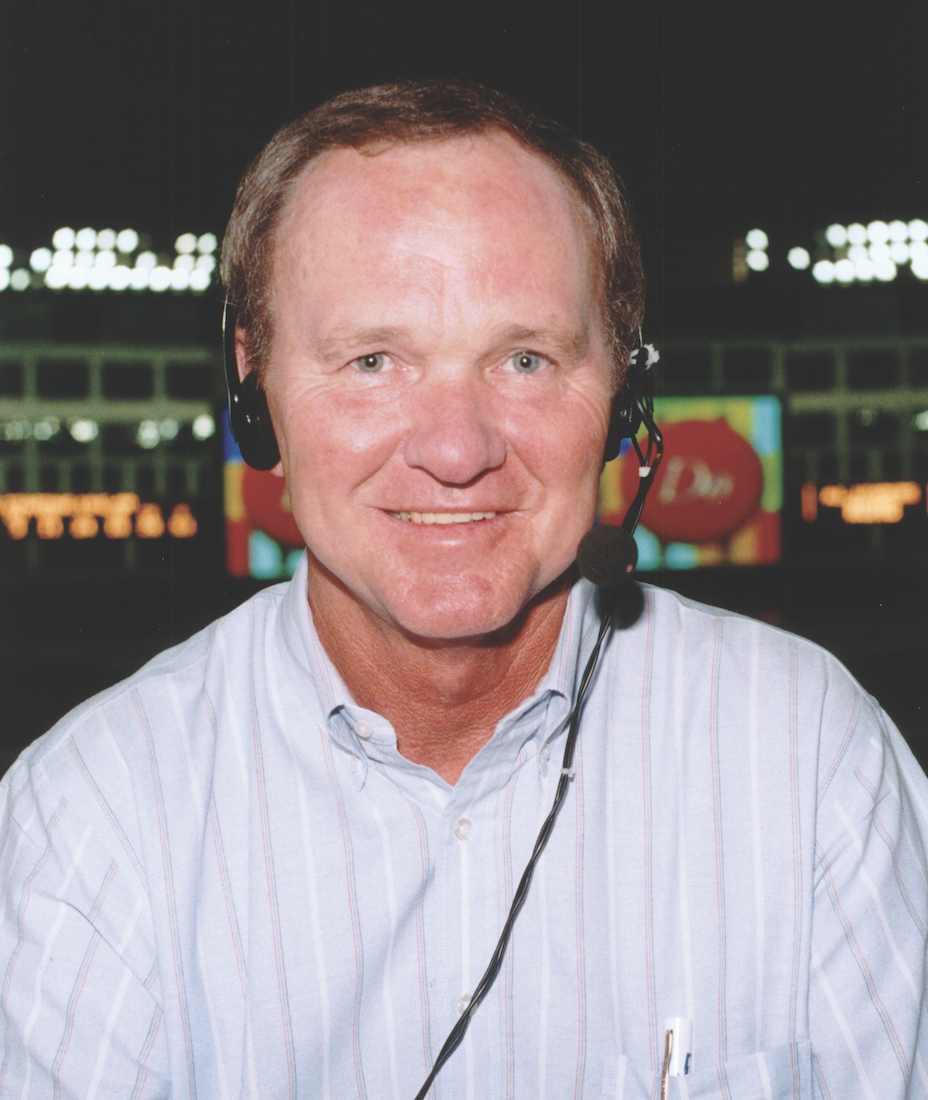

Tom Cheek

Baseball on the radio is an important part of the lives of countless people. The radio play-by-play announcer serves as the narrator of the game. The personal connections developed between fans and their favorite announcers can last for decades. The radio talent becomes the “voice of baseball” and the inside, personal connection that fans have with their favorite teams.

Baseball on the radio is an important part of the lives of countless people. The radio play-by-play announcer serves as the narrator of the game. The personal connections developed between fans and their favorite announcers can last for decades. The radio talent becomes the “voice of baseball” and the inside, personal connection that fans have with their favorite teams.

Tom Cheek was the voice of baseball and the narrator of summer for Blue Jays fans throughout Canada and beyond for almost three decades. Starting with the team’s first regular-season game on April 7, 1977, he shared the game with fans from February through October. He shared some of his favorite baseball moments and told stories about the people he knew and met. He shared his raw emotion when something good or bad happened during a game. He shared all that he knew about the game he loved so much. He shared it until a brain tumor made it impossible for him to continue in 2004. And then the sharing was gone.

When Cheek’s voice disappeared from the airwaves, it shook the very foundations of Blue Jays nation. Club President Paul Godfrey said as much in 2005: “When Tom suddenly stopped, it was like the whole organization stopped. That’s how much he means to the club.”1 It was as if a close friend had been taken away very suddenly, never to be heard from again. “I can’t tell you anyone who more epitomizes the heart and soul of the Toronto Blue Jays than Tom Cheek,” said Godfrey. “His voice has touched millions of fans over the years.”2

Thomas Fred Cheek was born on June 13, 1939, in Pensacola, Florida. His father, also named Tom, served as a World War II fighter pilot in the Battle of Midway in 1942. Following in his father’s footsteps, Cheek himself joined the military and served in the US Air Force from 1957 to 1960. While he was in the service he met broadcaster Red Barber.3 He met his future wife, Shirley, a native of Hemmingford, Quebec, while stationed in Plattsburgh, New York. They married in 1959 and soon had three children, Lisa, Jeffrey, and Tom.

Cheek knew from a young age that he wanted to be in broadcasting. After his discharge he went to school at SUNY Plattsburgh and then the Cambridge School of Broadcasting in Boston. He began his career in broadcasting as a disc jockey in Plattsburgh. His next job was in Burlington, Vermont, where he worked as a corporate sales manager and as sports director for a group of three radio stations including WBMT, which carried Montreal Expos baseball. He also called University of Vermont sports and was almost hired to take over as the full-time play-by-play announcer for the expansion Atlanta Hawks of the National Basketball Association.4

While in Burlington, Cheek found occasional work as a fill-in broadcaster for the Expos, Cheek said in an 1985 interview that broadcasting games for the Expos put him on the path to become the future Toronto Blue Jays radio play-by-play announcer. He made the 99-mile trip to broadcast games usually on Wednesdays in 1974 through 1976.5 His work with the Expos did not go unnoticed. According to John Lott, “His work convinced Len Bramson, a Toronto broadcast executive who was developing a coast-to-coast radio network for the expansion Blue Jays, to make Cheek the lead man in the radio booth.”6

The expansion Toronto Blue Jays announced in December 1976 that Tom Cheek would become the play-by-play announcer for the new club. Hewpex Sports Enterprises announced that the radio broadcast borders for the new club would cover a 14-city area across the province of Ontario with the possibility of adding more stations before the club began spring training for its first season. The network would extend to “Kingston in the East to Sarnia in the West, in Tiger Territory, and Timmins in the North,”7 With a 14-city network in place, and a radio announcer ready to go, all that was left for Tom Cheek to fulfill a lifelong dream was call his first game with his new club.

On a snowy April 7, 1977, with the temperature right around freezing, Bill Singer threw out the first pitch for the expansion Blue Jays against the Chicago White Sox at Exhibition Stadium. Upward of 44,649 fans including a young Wayne Gretzky, packed the ballpark to see Toronto’s first major-league baseball game. Trailing 2-0 in the first inning, Doug Ault hit the first home run in franchise history, which started the team’s comeback that day. The Blue Jays rallied and won, 9-5. Cheek said the win that day ranked as his top Blue Jays memory.8 There would not be much more for Cheek to cheer for the rest of the season or for a few years to come. The Blue Jays finished their inaugural season with a 54-107 record, 45½ games behind the New York Yankees. For the first six years of its existence, the team did not have a winning record. That started to change in the mid-1980s.

Fans tuning in to hear Cheek’s baritone voice over the years also heard the voices of his radio partners. From 1977 through 1980 former major-league pitcher Early Wynn called games alongside Cheek. Jerry Howarth replaced Wynn in 1981.

Cheek and Howarth constituted the play-by-play tandem of Blue Jays baseball for over two decades. The partnership covered the evolution of the franchise from an American League East bottom feeder to its rise to prominence starting in the 1980s, and then to its rise to the top of the baseball world with back-to-back World Series titles in 1992 and 1993. The duo stayed together for the duration of Cheek’s career.9

From the start, Cheek remained a constant in the radio booth, never missing a game until 2004. The Blue Jays’ fortunes started to turn in the mid-1980s and into the 1990s, and they won their first division title in 1985. A year before his death, Cheek recalled how he felt when that happened: “When George Bell dropped to his knees on the turf at Exhibition Stadium in 1985 as the Blue Jays won their first division title, I started thinking about all the guys who’d contributed over the years to get them there – and I choked up,” said Cheek. “You could hear the catch in my throat. I promised I’d never do anything like that again.”10

The Blue Jays were not yet in a position to go far in the playoffs. They lost the American League Championship Series to the Royals in 1985, the Athletics in 1989, and the Twins in 1991. They finally captured the pennant in 1992, becoming Canada’s first team to make it to the World Series. Members of the press seemed to be relieved by the club’s first pennant. “The next step for the Blue Jays, who have been carrying enough guilt for an entire country because of their three previous playoff failures, is the World Series, in which they will take on the Atlanta Braves beginning Saturday in Atlanta.”11

The Blue Jays beat the Atlanta Braves in six games to become the first team outside of the United States to win the championship. The Series was noteworthy when it came to Cheek and the broadcast. During Game Two of the series, the US Marine Corps accidentally displayed the Canadian flag upside down during the national anthem. This outraged Blue Jays fans but did not seem to bother pinch-hitter Ed Sprague, who hit a game-winning home run off Jeff Reardon, at the time baseball’s saves leader. The round-tripper was the first pinch-hit home run for the Blue Jays all season. And probably more prophetic than odd, before Sprague hit the home run, Cheek commented on the air, “Watch him hit a homer.”12

In Game Six, Cheek and Howarth went outside their normal broadcasting rotation once the Blue Jays took the lead in the top of the 11th inning. Normally, Cheek would call the first two innings of a game then turn the play-by-play over to Howarth for the next two innings and they would continue this pattern for the remainder of a game. Howarth called the top of the 11th as usual but after the mid-inning commercial break, Howarth turned the broadcasting call over to Cheek for the bottom of the inning. Howarth, in a grand gesture, was hoping to have Cheek call the Jays’ first-ever World Series win.

With two outs in the 11th, Cheek made the call that gladdened Blue Jays fans: “Timlin to the belt. … Pitch on the way. … There’s a bunted ball, first-base side. … Timlin to Carter and the Blue Jays win it! The Blue Jays win it! The Blue Jays are World Series champions!” As fans across Canada began to celebrate, Cheek went on: “The Blue Jays have won the World Series so Canada, let it all out, it’s party time! It was a long time coming but it’s here.”13 Canadians across the nation celebrated alongside Cheek well into the night.14

The Blue Jays won the pennant again in 1993, and one of the most dramatic endings to a World Series occurred in Game Six. With Toronto leading three victories to two, the Philadelphia Phillies led 6-5 going into the bottom of the ninth inning. Phillies closer Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams was on the mound hoping to send the World Series to a decisive Game Seven. The Blue Jays’ Rickey Henderson started the inning with a walk. Devon White flied out to deep left field. Paul Molitor singled.

With two on and the count 2-and-2, Joe Carter cemented his legacy as a Blue Jays legend by driving Williams’s next pitch over the left-field wall to win the Series in a walk-off. Fans over the years have pointed to Cheek’s call of Carter’s home run as perhaps his best-known call.

Cheek reflected on the call at spring training camp in Florida in 2005. “I was looking for something to say, and Joe gave it to me because he was jumping up and down. I was merely mentioning to him through the airwaves that you’ve got to touch all the bases.” Those listening heard that call live with the type of raw emotion that often engulfs someone who has seen something almost magical. “Touch ’em all Joe, you’ll never hit a bigger home run in your life!”15 It has become one of the most famous lines in baseball broadcasting history.

Over the seasons Cheek acquired a unique insider’s view of the club that very few in the organization had achieved. So he decided to share some of his knowledge about the team and in 1993 he and co-author Howard Berger released Road to Glory: Sixteen Years of Blue Jays Fever, which chronicled the first 16 years of Blue Jays baseball. Jim Proudfoot of the Toronto Star opined that “Cheek, who’s witnessed every inning the team has played, is perceived as the ultimate insider,” and added, “His viewpoint was bound to be uniquely revealing.”16 Cheek wrote of why Peter Bavasi abandoned the club presidency in 1981 and why Tony Fernandez, in Cheek’s view, abandoned the team in 1987. Baseball fans loved the book and made it a best-seller. Bookstores all across Canada had a hard time keeping the book on their shelves.17

After the dramatic World Series win in 1993, the Blue Jays began to slide. For the rest of Cheek’s time with the team, it didn’t finish any higher in the standings than third.

On Thursday, June 3, 2004, the Blue Jays lost to the Oakland Athletics, 2-1, in 11 innings but the game itself took a back seat to what happened in the Blue Jays radio booth that night. Cheek’s father, Tom Sr., had suffered a fatal heart attack the previous night and so Tom rushed home to be with his family. After 4,306 regular-season games and 41 postseason contests without missing a broadcast, Cheek was not in the booth that night. Howarth handled the game with color commentary for a few innings provided by injured Jays outfielder Frank Catalanotto.

Howarth took a moment to reflect on the now-broken broadcasting streak of his longtime partner. “Having sat here for 23 years, it’s incredible because of all of the factors that go into broadcasting a game,” Howarth said. “It’s a testament to his professionalism, to his commitment to fans. It takes a lot to keep a streak like that alive. There are several factors, like health, graduation, funerals, that can intrude.”18 Blue Jays President Paul Godfrey weighed in: “A feat of this magnitude does not occur without a great deal of sacrifice and perseverance from the Cheek family. Tom’s dedication and contributions to the Toronto Blue Jays organization are immeasurable.”19

Former major-league pitcher Tom Candiotti compared Cheek’s streak to that of another baseball ironman, Cal Ripken Jr. So did former Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick, who said, “He was sort of like Cal Ripken, in that you knew he was going to show up every day, you knew he was going to be there with the same pride, the same dedication to excellence. You could always count on Tom to bring his very best every day.”20 Cheek accepted the kind words but would not accept the comparison of his streak with Ripken’s. “There will only ever be one streak in baseball,” Cheek said. “That would be the one that Cal Ripken put together. He was out on the field doing it every night while I was just up there watching.”21 Cheek returned to the booth soon after the funeral and tried to get back to doing what he loved. His return did not last long. Cheek soon found himself in the biggest battle for his own life.

Cheek felt ill a week after returning to the booth. Tests at a Toronto hospital indicated a brain tumor. On June 13, his 65th birthday, Cheek underwent surgery to remove the tumor. “Everyone at the Toronto Blue Jays wishes Tom a speedy recovery,” club President Paul Godfrey said. “Our thoughts are with the entire Cheek family, and we hope to see Tom back in the broadcast booth very soon.”22 And Cheek returned to broadcasting six weeks later despite chemotherapy treatments that impaired his short-term memory. On July 23, 2004, he called two innings of the Blue Jays game against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.23 Cheek was able to return and broadcast home games on a limited basis while undergoing treatments, but he was replaced by guest announcers when the team was on the road. His popularity with the fans never wavered during his absence. Thousands sent him best wishes and wished the longtime broadcaster a speedy recovery.

The Blue Jays invited Cheek for an on-field presentation at SkyDome on August 29, 2004. Mike Wilner served as one of the replacements for Cheek as he recovered from surgery. Cheek and Wilner sat in the dugout looking out onto the field and talking before the ceremony. Cheek soon noticed that a portion of the 400 level was covered with a blue tarp. “It was amazing to see the look of recognition, and then of genuine embarrassment move across his face,” Wilner remembered. “He kept saying ‘You have GOT to be kidding me,’ because he honestly didn’t believe that just showing up to work every day deserved such major praise.”24

An emotional crowd of 44,072 was there to honor Cheek. The Blue Jays had played the Yankees that weekend and had not performed well so the team and its fans were eager to have something to cheer about. Cheek sat with his wife and watched as the Blue Jays removed the blue tarp to officially add him as the newest member of the team’s Level of Excellence.

Geoff Baker of the Toronto Star described the scene: “They sat through a video montage on the SkyDome’s JumboTron, one that replayed Cheek’s greatest calls, including Toronto’s first division title clinch in 1985, Dave Stieb’s no-hitter in 1990, and Joe Carter’s decisive home run in the 1993 World Series. Eyes throughout the stadium turned moist as photos from Cheek’s younger days flashed on the screen, accompanied by the strains of Frank Sinatra’s “It Was a Very Good Year.”25

Cheek made his way to the podium and addressed the crowd. After making a crack about the Yankees, he addressed his medical condition. “I’ve been fighting a situation now for over a month, almost two months now,” he said. “We’re doing the best we can to stay ahead of it. A brain tumor. We’re dealing with it.”26 Even Yankees radio announcer John Sterling had to take a moment to compose himself. Cheek, the consummate professional, went back to the Blue Jays radio booth after the ceremony to take his place and get ready for the game.

Tom’s wife, Shirley, told a reporter almost a decade later how that day changed his life. Cheek had told her that he had never imagined the connection he had forged with the fans and how important that connection was to them. “I never could really get the point until somebody said, and a lot of others followed, ‘Since I was a little kid, you’ve been giving the sound of summer.”27 It finally clicked for him. “He had so many people that would say he was the voice of summer,” she said. “‘I listen to you on the lake. I listen to you on the tractor out in Saskatoon, or, you know, wherever. But I think it really hit home when he saw that his name was going up on the wall and how much he had meant to the fans listening on radio.”28

Cheek wanted to bounce back and try to return to the booth for good in 2005. He was nominated for the National Baseball Hall of Fame Ford C. Frick Award for the first time before the 2005 season. He was honored to be nominated and even though he didn’t win it (San Diego Padres announcer Jerry Coleman did), he looked forward to getting back into the booth to call Blue Jays games in the coming season. “I can’t wait to get out here and get back on the field and get back in the booth,” he said.29

Early in spring training, Rogers Media announced that Cheek would be back in the booth for Opening Day with Jerry Howarth. But Cheek suffered a setback when in March an MRI revealed that the cancer had returned and another tumor had formed. Rogers Media canceled his return pending the results of his surgery. Cheek, determined to beat the odds and do his job, made one more appearance in the radio booth for the Blue Jays on Opening Day.

“The last time Cheek was in the booth was Opening Day 2005,” Mike Wilner wrote, “when he joined Howarth and Warren Sawkiw at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida, close to his home in Oldsmar, and Jerry insisted he get on the mic and call a few pitches. Reluctantly he agreed, and took over as Orlando Hudson came to the plate in the top of the third. Hudson homered, and so did Vernon Wells behind him, and that was enough for Cheek.”30 Cheek’s career as a broadcaster essentially ended that day.

On October 14, 2005, with his wife; his three children, Jeff, Lisa, and Tom; and his seven grandchildren present, Cheek died at the age of 66 at his Florida home. “It’s difficult to put into words the overwhelming sense of grief and loss shared today by the Blue Jays family, the city of Toronto, the extended community of Major League Baseball and its many fans,” Blue Jays President Paul Godfrey said. “He was a great goodwill ambassador for baseball in Canada.”31

Cheek did not believe that he deserved a lot of praise for just showing up to work every day. He seemed genuinely embarrassed that the Blue Jays added him to their Level of Excellence in 2004. Despite his resistance, others sought to reward Cheek for his efforts in promoting baseball. The Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame honored Cheek with the Jack Graney Award for his contributions to baseball in Canada in 2001. The Canadian Sports Hall of Fame established an annual Tom Cheek Media Leadership Award, with Cheek being honored with the first award in 2005. The award was established to recognize media members who help promote Canadian sports “in an extraordinary and enduring way.” A website was created that sold wristbands to help fund cancer research. The year after Cheek died, the Blue Jays wore a white circular badge with the letters “TC” and a microphone in black on their left sleeve.32 And in 2013 Cheek was honored with the Ford C. Frick Award and earned enshrinement into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Baseball over the radio serves as the preferred way of catching baseball games for countless numbers of baseball fans all over the world. Even though television broadcasts have long replaced the radio as the most used communication device for watching baseball, there are still many who will turn their television volume down and listen to their favorite radio announcer call the game. The best of the baseball radio talent through the years: Mel Allen, Vin Scully, Gene Elston, and Ernie Harwell have become the voice of baseball for many. “Tom Cheek was the voice of summer for generations of baseball fans in Canada and beyond,” said Hall of Fame President Jeff Idelson in a press release announcing the Ford C. Frick Award for Cheek. “He helped a nation understand the elements of the game and swoon for the summer excitement that the expansion franchise brought a hockey-crazed nation starting in the late 1970s.”33

Tom Cheek “was more than just a broadcaster,” said Len Bramson, the one-time talent-hunting guru who lured him to Toronto from Vermont hoping he’d establish an identity for the newly awarded Jays franchise. “He was big, had the voice. He was cordial with everybody, he could talk to anybody. In front of a crowd, he was outstanding. He did it with no notes. He just loved to talk about baseball.”34 Baseball fans all over Canada and beyond loved to hear him talk about baseball.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Shi Davidi, “Cheek Up for Honour,” Toronto Star, February 22, 2005: E06.

2 Davidi.

3 Tom Cheek, Road to Glory (Toronto: Warwick Publishing, 1993), 7-30.

4 Cheek, Road to Glory; Canadian Press, “Tom Cheek, Voice of Toronto Blue Jays, Dies.” http://www.americansportscastersonline.com/tomcheekmemoriam.html.

5 Home Town Cable Network, “Toronto Broadcaster Tom Cheek – 1985,” YouTube, October 3, 2016. https://youtu.be/htU0td0aavA.

6 John Lott, “Voice of Summer; Tom Cheek, Who Brought His ‘Folksy, Intimate’ Style to Jays Broadcasts For 27½ Years, Is Finally Headed to Cooperstown,” National Post, Toronto, December 6, 2012: B5.

7 Neil MacCarl, “Blue Jays Polish Skills in Winter Loops,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1976: 54.

8 Sam Jarden, “April 7, 1977: Blue Jays Play Their First Ever Game,” The Sporting News, April 7, 2020. https://www.sportingnews.com/ca/mlb/news/april-7-1977-toronto-blue-jays-play-their-first-ever-game/17if403ulmlq418soqp71hx20t. “Tom Cheek, Voice of Toronto Blue Jays, Dies.” http://www.americansportscastersonline.com/tomcheekmemoriam.html.

9 CatchTheTaste, “1991: Behind the Scenes with Tom Cheek and Jerry Howarth,” YouTube, July 6, 2019. https://youtu.be/ILDzMImogvc.

10 “2013 Ford C. Frick Award Winner Tom Cheek,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/awards/frick/tom-cheek.

11 David Bush, “O, Canada! A’s Fall, 9-2, Blue Jays win A.L. pennant, finally reach their 1st World Series,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 15, 1992: C1.

12 “Jays: Memories of ’92 and ’93 Series,” Toronto Star, August 11, 2018: S4.

13 Eye Flow, “Toronto Blue Jays World Series 1992 Tom Cheek,” YouTube, October 21, 2014. https://youtu.be/xODky9oDqMI.

14 Canadian Press and Herald Staff, “Blue Jays Fever: Canada Gets World Series,” Calgary Herald, October 15, 1992: A1.

15 Jeremy Sandler, “Blue Jays Broadcaster Misses Out on Hall of Fame Award,” National Post, February 23, 2005: B10.

16 Jim Proudfoot, “Cheek’s Book on Blue Jays a Treasure Hunt,” Toronto Star, July 6, 1993: D4.

17 Proudfoot.

18 Geoff Baker, “Sadly, Cheek Finally Misses a Jays Game,” Toronto Star, June 4, 2004: C04.

19 Geoff Baker, “Sadly, Cheek Finally Misses a Jays Game.”

20 Geoff Baker, “Tom Cheek: Ironman of the Airwaves,” Kitchener-Waterloo (Ontario) Record, October 11, 2005: D2.

21 Geoff Baker, “Blue Jays Honor Emotional Cheek,” Toronto Star, August 30, 2004: E07.

22 “Jays Announce Cheek Has Brain Tumor Removed,” Detroit Free Press, June 15, 2004: 8E.

23 “Touching All the Bases,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 24, 2004.

24 Mike Wilner, “Wilner on Jays: Remembering the Great Tom Cheek,” Sportsnet Canada, July 3, 2013, https://www.sportsnet.ca/baseball/mlb/wilner-on-jays-remembering-the-great-tom-cheek/.

25 Geoff Baker, “Blue Jays Honor Emotional Cheek.”

26 Geoff Baker, “Blue Jays Honor Emotional Cheek.”

27 John Lott, “Voice of Summer; Tom Cheek, Who Brought His ‘Folksy, Intimate’ Style to Jays Broadcasts For 27½ Years, Is Finally Headed to Cooperstown.”

28 Lott.

29 Jeremy Sandler, “Blue Jays Broadcaster Misses Out on Hall of Fame Award,” National Post, February 23, 2005: B10.

30 Mike Wilner, “Memories of Cheek, Who Touched So Many Lives,” Toronto Star, March 20, 2021: S1.

31 Associated Press, “Tom Cheek, 66; Announcer Called Blue Jay Games for 27½ Seasons,” Los Angeles Times, October 11, 2005, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2005-oct-11-me-cheek11-story.html; CBC Sports, “Tom Cheek, Longtime Voice of Blue Jays, Dead,” October 9, 2005, https://www.cbc.ca/sports/tom-cheek-longtime-voice-of-blue-jays-dead-1.528332.

32 “Voice of the Blue Jays Tom Cheek Dies,” Pittsburgh Tribune Review, October 9, 2005.

33 “Tom Cheek: Late Blue Jays Announcer Wins Top Hall of Fame honor,” Sherman Report, December 5, 2012. http://www.shermanreport.com/tom-cheek-late-blue-jays-announcer-wins-top-hall-fame-honor/.

34 Geoff Baker, “Tom Cheek: Ironman of the Airwaves,” Kitchener-Waterloo Record.

Full Name

Thomas Fred Cheek

Born

June 13, 1939 at Pensacola, FL (US)

Died

October 9, 2005 at Oldsmar, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.