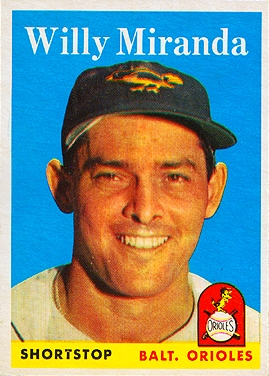

Willy Miranda

Willy Miranda epitomized the “good field, no hit” shortstop. He was a lot more than good in the field, though—Tom Lasorda, to name just one, thought the flashy little Cuban was the best he ever saw at short.1 Wielding the same battered, patched, and secretly doctored glove for nearly his entire pro career, Miranda was so much fun to watch that Paul Richards, his manager with the Baltimore Orioles, gave him credit for saving the franchise in its early years.2

Willy Miranda epitomized the “good field, no hit” shortstop. He was a lot more than good in the field, though—Tom Lasorda, to name just one, thought the flashy little Cuban was the best he ever saw at short.1 Wielding the same battered, patched, and secretly doctored glove for nearly his entire pro career, Miranda was so much fun to watch that Paul Richards, his manager with the Baltimore Orioles, gave him credit for saving the franchise in its early years.2

Miranda was in the vanguard of brilliant Latino glove men who hit the majors in the 1950s. Half a century later, some more recent comparisons come to mind. Mario Mendoza, the “no hit” benchmark, is one—but while Mendoza was a fine defender, he was not among the elite shortstops. With the bat, even though author Tom Boswell called .200 “The Miranda Line” instead, 3 Willy was actually a step up from Mendoza and a shade below his countryman Rey Ordóñez.4 Ordóñez had his own unique fielding style but may be the most similar shortstop overall. Both Rey and Willy moved like dancers and wowed the fans.

Another small but spectacular Cuban shortstop was Germán Mesa (born 1967). His audience outside of the island was limited, but he can still be seen on YouTube. Ironically, Mesa’s presence on the national team in the 1990s blocked Ordóñez and prompted his defection.5 Cuban writer Rogério Manzano put it in historical perspective: “In the epic of the Cuban national pastime there are three men who defied the laws of legerdemain. . .Willy Miranda, Germán Mesa, and Rey Ordóñez are of that special caste of shortstops.”6

Miranda should also be remembered for his generous nature and true heroism. Lasorda, a teammate in Cuban winter ball, said, “Nobody helped me on and off the field like him.” Another member of the Almendares team, Andrés Fleitas, called Miranda “a friend that could not be equaled.”7 Twice in later years, this man risked his life not only for family but also for people he barely knew.

Guillermo Miranda Pérez was born on May 24, 1926. His parents always called him Willy, with a ‘y’8 although the U.S. press and Miranda’s baseball cards used “Willie” more, that spelling is used here only when it comes directly from a quotation.

Until 1976 Cuba was divided into six provinces. Miranda’s hometown of Velasco was in the easternmost, Oriente. Since the subdivision, Velasco is now in Holguín province, which today offers an unusual mix of sugarcane fields, forested mountains, dirty nickel mines, and beach resorts. In Willy’s youth, however, it was a largely rural place. “Velasco was a very small town,” said his son, Willy Miranda, Jr. “It was really a neighborhood.”

Willy was the fifth of seven children born to Teodoro “Pilo” Miranda and Isolina Pérez. For that reason, he always wanted to wear the uniform number 7. The only time he couldn’t was with the Yankees because Mickey Mantle had it. The oldest Miranda child, Fausto (1914-2006), became the dean of Cuban sportswriters. In later life, Fausto was sports editor for Miami’s El Nuevo Herald, which he helped launch in 1976. After him came a sister named Aïda, followed by Teodoro Jr. (“Puri”), Irma, and Willy. A younger brother, Raúl (1929-1985), was also a noted sportswriter. Last was another girl named Isolina (“Chicha”).

Teodoro Sr. was a railroad engineer who had studied for a time in the United States. After his return to Cuba, he was put in charge of small train stations in Oriente. The main business was loading operations for the local sugar mills. Isolina was a local girl who stayed at home with the children after marriage. The couple first lived in the city of Puerto Padre, which today is in Las Tunas province.

Pilo Miranda was a big man, standing 6’3”, and his grandson Willy Jr. remembered that he was very stern. Though Pilo did not play baseball, he liked the game, so young Willy started playing practically from the time he took his first steps. In 1975 he joked, “My father say he spent all his time teaching me to field and then it became too late to make me a hitter.”9 In a 1950s radio interview, comic actor Joe E. Brown ribbed, “Your father never gave you a bat?”10 Miranda did learn how to swing from both sides of the plate, but broadcaster Ernie Harwell remarked, “They said Willy hit left, right and seldom.”11

Fausto Miranda recalled that when his little brother was 8 years old, throwing a ball against a wall and catching it, Willy would call the play, imagining himself as the shortstop for the New York Yankees. Nearly 20 years later, in 1953, he would realize his childhood dream. Willy had told Fausto that when he started playing ball, he would make it to the majors no matter what anyone said, but being with the Yankees was the happiest time of his life as a pro ballplayer.12 “Once you play for the Yankees,” said Willy Jr., “you become part of their family.”

It was also when Willy was 8, around 1934, that the Miranda family moved 400 miles west to Havana. (Fausto had gone there the previous year, launching his career in journalism.) In 1940 Willy joined a youth baseball team, Club Juvenil del Parque José Martí. The following year he went to HH Maristas de La Víbora, a Catholic school run by the Marist Brothers order, and played for its team.13 Cuban author Francisco José Moreno offered a not-so-complimentary view of the way the game was played there, though. “In the self-conscious but whimsical style of the Maristas school. . .looking good was as important as being good. . .Willy Miranda. . .had a genius for making easy chances look difficult.”14 Miranda’s 1958 baseball card said exactly the opposite.

From 1942 to 1947, Willy played with Club Teléfonos in Cuba’s National Amateur League. For firsthand knowledge of that time, we are blessed by the phenomenal memory of Cuban legend Conrado Marrero. The pitcher, who turned 98 in 2009, was the ace for Cienfuegos Sport Club in the same league. “[Miranda] was very young when he started his career in baseball,” said Marrero. “Quite rapidly he learned the techniques. He stood out on defense—he fielded well and had a very good arm, getting outs from deep in the hole at short. Several times I saw him make legendary plays.

“In particular he was a man who liked to talk a lot and was very affectionate with everyone.”

Although two new integrated amateur leagues sprang up in the 1940s, the one in which Willy played was the domain of white-only social clubs and remained segregated until 1959. This also meant that Cuba’s international amateur teams excluded Afro-Cubans until 1950, when Edmundo “Sandy” Amorós and Justiniano Garay joined the squad. In 1946, Miranda made his first appearance for Team Cuba in the fifth Central American Games, held in Barranquilla, Colombia.15

Miranda married Amada Suárez on March 11, 1946, in Havana. They would have four children together: three sons (Guillermo Jr., Eduardo, and Alejandro) and a daughter (Rosalia).

Willy turned pro in 1948, thanks to Washington Senators scout Joe Cambria, who signed a legion of Cubans over the years. He went to Sherman-Denison, Texas, north of Dallas and just south of the Oklahoma border. Fortunately, he had plenty of company from home. In addition to manager José Rodríguez, seven more of his countrymen also played on the team, though Willy was one of just two Cuban regulars.16

The Twins were champions of the Big State League (Class B) that year. Miranda was a key part of the team and had already established himself as a crowd-pleaser. That June columnist Bill Thompson, who covered the rival Paris Rockets, wrote: “Willie Miranda, Sherman-Denison’s classy little Cuban shortstop, is running second to Buck Frierson in a popularity contest at Twins Park. . .Miranda, 20 years old, is the speedy little ‘flea’ who robbed the Rockets of hits several times during the recent Twins-Rockets stand here.”17 As an adult, Miranda stood 5’9 1/2” and weighed 150 pounds, often less. One may also note that like so many ballplayers, he shaved a couple of years off his age.

In the winter of 1948-49, Miranda played his first of 12 seasons in Cuba’s professional winter league. He joined the Almendares Alacranes (Scorpions), with whom he would spend nearly all of his Cuban career. Two of Willy’s future teammates with the Senators were there too: catcher-manager Fermín “Mike” Guerra and Conrado Marrero. Marrero said in 2009, “He was a giant of his time on defense, making countless fine plays at shortstop, but his bat did not help him as he himself would have liked.”

Willy backed up the veteran Avelino Cañizares, but he emerged as Rookie of the Year. Clearly the voters recognized him for his fielding, as he batted just 9 for 41 (.220) with two RBIs. The Alacranes won the Cuban championship, the first of five for Willy. The team also featured Santos Amaro and Agapito Mayor, plus Americans such as Monte Irvin, Sam Jethroe, Al Gionfriddo, Clyde King, and actor-to-be Kevin “Chuck” Connors. They went on to win the inaugural Caribbean Series, sweeping all six games. Miranda was hitless in his only at-bat behind Cañizares.

Back in the U.S. in 1949, Miranda moved up to Chattanooga in the Southern Association (Double A). It was then that Willy bought the glove he called “Old Faithful”—a big, heavy Bob Dillinger model. Bob Maisel in Baseball Digest described Willy’s “best friend” after the 1957 season: “It’s as stiff as a board and even his teammates can’t understand how Willy can catch a ball, let alone pull off the miraculous plays that are a constant source of amazement to followers of the Orioles. Willy is constantly repairing the old piece of leather.” Maisel depicted the countless multi-colored patches, solutions, restringing, and major surgery that kept the glove in action.18

In 1975 writer John Steadman revealed the secret of Old Faithful’s stiffness: Miranda had also resorted to illegal means. Inside the fingers were wooden tongue depressors and cut-up sanitary socks. The puppetry helped Willy, who preferred to keep his hand out of the glove as much as possible (only his thumb and little finger actually went all the way inside). Many players knew. . .but not the umpires.19 20

In the winter of 1949-50, Willy split the shortstop duties for Almendares with both Avelino Cañizares and Eddie Pellagrini from the St. Louis Browns. He hit .258 in 97 at-bats. The Blues (as they were also known) repeated as Cuban champions and proceeded to the Caribbean Series. The Cuban team was just 3-3 as Panama pulled off an upset victory. Willy was 3 for 7 with a double and three RBIs.

Miranda was in the Senators camp in the spring of 1950, interpreting for Conrado Marrero, among other things. When the season broke, though, he remained at Chattanooga. While he hit just .248, Willy hit his first pro homer that summer and “amazed the folks with his sensational fielding.”21 In the winter, he was named to Cuba’s all-star team for the first of three times. Along with a .294 average, he had a homer and 16 RBIs.

In February 1951, during spring training, veteran pitcher Bobo Newsom told Washington manager Bucky Harris that Miranda was the finest fielding shortstop he had seen in his 20 years of baseball.22 (Newsom had spent 1949-50 at Chattanooga; Andrés Fleitas was his catcher.) Despite this praise, and even though Willy had impressed Harris, doubts remained about his hitting. Yet despite indications that he would open the season in Tennessee again, he stuck with the Senators as their sixth infielder. He flew his father up to Washington to visit at Griffith Stadium.

While Willy rode the bench for the first few weeks of the season, he enjoyed the Cuban camaraderie. A 1951 photo in Life magazine shows him along with Mike Guerra, sharply dressed pitcher Julio “Jiquí” Moreno, and Marrero in a favorite Cuban hangout, Alamo’s Hollywood Barber Shop. Also on hand was Cuba’s ambassador to the U.S., Luis Machado.23

On May 6, Miranda made his big-league debut. It was an oddity, as he played first base for the only time in the majors, substituting for Mickey Vernon. Vernon had turned his ankle in a pickoff play in the top of the ninth at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. Sitting behind Sam Dente and Gene Verble, Willy did not appear again until May 22. In Washington that night, he got his first start and first base hit, off Saul Rogovin of the White Sox. Miranda went 4 for 9 in seven games before the Nats returned him to Chattanooga on June 22. Pete Runnels, who broke in as a shortstop, got his first callup.

That October 24, the Senators traded Willy (whose age was still given as 23 rather than 25)24 to the Chicago White Sox for third baseman Floyd Baker plus cash. It was a curious deal because the White Sox already had a very similar player in Venezuelan Chico Carrasquel. One report said that Lou Boudreau, new manager of the Boston Red Sox, was actually willing to trade Ted Williams for Carrasquel—and that Chicago general manager Frank Lane turned him down. Boudreau thought Lane’s answer might be different once Willy joined the White Sox, but Lane said, “In Carrasquel and Miranda we think we’ve got the two finest fielding shortstops in baseball. Miranda hasn’t hit, but he’s mighty good in the field and he can run like hell. [Manager Paul] Richards wanted him for insurance, and we figure he might be able to fill in at second, short, or third.”25

The year 1952 was odd for Willy as he ping-ponged between the White Sox and Browns. On June 15, he went with Al Zarilla to St. Louis for Leo Thomas and Tom Wright—but returned to Chicago less than two weeks later (June 28) on waivers after Carrasquel broke a finger. One writer, Harry Grayson, viewed “Trader Frank” Lane and Bill Veeck of the Browns as “circumventing the spirit of the rule” and “making a joke of baseball law.”26 Dan Daniel of the New York Telegram added, “Lane and Veeck are my friends, and I wish them well. But they should stop being so pally in their player moves.”27

Nonetheless, on October 16 Lane dealt Miranda back to Veeck, along with Hank Edwards, for Tommy Byrne and Joe DeMaestri. Veeck would later comment, “When I was in St. Louis, I’d call Frank up and say, ‘Things are dull around here. Let’s do something. . .This is the kind of deal made just to whip up a little excitement. To try to make it look as if big things are happening. It’s like trading a $200,000 dog for two $100,000 cats.”28

During the winter of 1952-53, Miranda fought off the challenge of José Valdivielso for the shortstop job with Almendares. When he got back to St. Louis, Willy roomed with Satchel Paige on the road and found that even though he was a white Cuban, he was none too welcome in white establishments. In addition, he saw barely any action for the first three months of the 1953 season. Sitting behind Billy Hunter, for whom the Browns had paid $150,000, he got just 6 at-bats in 17 games. “Willie is the last word in fielding,” said manager Marty Marion, who taught the young shortstop much about the position, as Conrado Marrero recalled hearing. “But the big question is his hitting.”29

On June 12, though, his fortunes changed. The New York Yankees bought him from the Browns (the amount was variously reported at $10,000 or $25,000). Casey Stengel wanted him as insurance for Phil Rizzuto, who was then nearly 36 and starting to show his age. “Yes, almost too good to be true,” said Willy. “I no like sit on the bench all the time. . .lose ambition, no good.”30 He later added, “All the time my two idols in baseball are Marty Marion and Phil Rizzuto, the two greatest shortstops. So first I play for Marion in St. Louis and now I am with Rizzuto.”31

Miranda got into 48 games for the Yankees, becoming their first Cuban player since Ángel Aragón and Armando Marsáns, back in the World War I era. One highlight was his first big-league home run. It came on June 24 at Yankee Stadium, dropping into the first row at the right field foul pole, 296 feet away.32 Again the benefactor was righty Saul Rogovin of the White Sox. The homer was one of only six in the majors for Willy, including an inside-the-parker; they came roughly once in every 400 plate appearances.

Willy was on the Yankees’ roster for the World Series. Opposing manager Charlie Dressen of Brooklyn jibed, “His weakness is pitched balls.” Miranda’s father and brother Fausto made the trip from Havana. Although the reserve did not see any action in the Series, “even being part of the spectacle was enough,” sportswriter Milton Richman noted in 1977. Willy said, “I told my father, ‘Look Pop, I got the New York Yankees’ uniform on and I’m in the World Series. This is the top. You cannot go any higher, so don’t ask for any more.’ My father died a few years later.”33 In addition to winning a ring, his teammates voted him a three-quarters share of the victors’ prize money.

Returning to Cuba shortly after the Series ended, Miranda was fortunate to avoid serious injury or possible death. Willy, who was ready to go hunting, put his .22 rifle down to greet a friend. His seven-year-old son, Willyto (whom Conrado Marrero remembered as a mischievous lad), accidentally discharged the weapon. Miranda escaped with just a wound on his upper lip, which did require some plastic surgery. Still, he didn’t miss a game for Almendares.34

In fact, the winter of 1953-54 was Willy’s best offensive season in Cuba, as he batted .304 and won his second all-star honor. Cuban baseball author Jorge Figueredo observed that Miranda was “always recognized as the best fielding shortstop in the league.”35 Manager Bobby Bragan led the Alacranes to the Cuban title, but they went just 3-3 in the Caribbean Series behind Caguas-Guayama of Puerto Rico. Willy was 4 for 22 (.182) and struck out nine times.

That winter the Miranda family also hosted Mickey Mantle, who’d had surgery on his chronically bad right knee in November 1953. Although import quotas meant that Mickey was not eligible to play ball in Cuba that winter even if he had been available, he did enjoy the atmosphere as he rehabbed his leg.

Willy returned to the Yankees in 1954 and continued to spell Phil Rizzuto, whose playing time was declining further. In 1996, the Scooter said, “It was a pleasure to watch him from the bench. Seeing him, he taught me many things on how to cover shortstop — and I thought I knew it all.”36

One amusing moment that year came in a game between the Yankees and the White Sox, as Stengel tried to use Willy as a Spanish-language bench jockey against Minnie Miñoso. Casey was unaware, though, that the Cubans were old friends. Miñoso put on a show, shaking his fist and shouting while in reality accepting Willy’s dinner invitation. The Old Professor then blamed himself for Minnie’s game-winning triple.37

On November 17, 1954, Miranda became part of the 17-player trade with the Orioles, the biggest swap between two teams in big-league history. The deal brought Bob Turley and Don Larsen to New York as well as Billy Hunter, the man who had started ahead of Willy with the Browns. Hunter was also a flashy fielder, yet Orioles manager Paul Richards (who had come over from the White Sox that September) thought more of Miranda. “Getting down to Willie Miranda,” said Richards as he defended his move, “he’ll show Baltimore fans that he is even a better shortstop than Hunter, and more reliable. And Willie should hit as well.”38

Almendares repeated as Cuban champions in 1954-55, again under Bobby Bragan, but the Caribbean Series was another disappointment. The Alacranes finished third at 2-4, while the Santurce Cangrejeros of Puerto Rico (who fielded perhaps the finest winter ball club ever that year) were the victors.

With the Orioles in 1955, Miranda stepped right into the everyday lineup, showing what he could do early on. In his first game back at Yankee Stadium on April 20, even though he was 0 for 4, he was sensational in the field as the Orioles won 6-3. “He made three spectacular stops, participated in a pair of ‘picture’ double plays, and drew more applause than any other player on the field.” 39

What made his feats even more remarkable was that Willy was sick with a stomach bug and fever, and he was worried even sicker because his wife Amada was in serious condition awaiting the birth of their fourth child. Casey Stengel remarked, “They said we gave ’em a bunch of lemons in that trade last winter, but you saw what that little guy at shortstop did to us out there, didn’t you? I kept tellin’ everybody that Miranda’s got a lot of class.”40

Miranda wound up having his best year at the plate in the majors. He posted career highs in average (.255) and RBIs (38), outhitting Billy Hunter. He also committed 34 errors, but that was a consequence of his range and his willingness to try for any ball he thought he could reach. In 1988 a man named Michael Hilton, who was a great fan of Willy’s as a boy, wrote an essay in Harvard magazine called “Going for It—and Failing.” Hilton proposed that what he called The Willie Miranda Syndrome was “a very valuable thing.”41 Investors recognize it as the classic concept that one must accept risk to obtain reward.

Indeed, after the ’55 season, the Orioles rewarded Willy. Assistant general manager Jack Dunn III said Miranda got a ‘substantial increase affording him the best contract he has had in professional baseball.’”42 The club also helped by paying Willy in Cuba, where the tax rates were more beneficial.

On the Baltimore team doctor’s advice, Willy quit the winter season in January 1956 to rest and regain weight.43 He remained an everyday player that summer, though his average tailed off to .217, including an 0-for-41 drought in August. Yet the crowd at Memorial Stadium remained behind him on August 21. “There wasn’t one boo. Instead he got a big cheer of encouragement.” Miranda then broke out of his slump with a triple, wrenching his shoulder with a headfirst slide and missing the next four games (though he gamely stayed in for the next half-inning in the field).44

A sad moment near the end of that season came when Miranda warned teammate Tom Gastall about the small plane he had recently bought. “Don’t go up in that thing,” were Willy’s words, and as fate would have it, the catcher died in a crash.45 In fact, Gastall had asked the shortstop to go with him. “If I had gone along, maybe I would have died,” Miranda said.46

That winter the Orioles played hardball with Willy, sending him a contract that called for a cut in pay from $12,000 to $10,000. He refused to sign it and held out for three weeks ahead of the 1957 season. The Orioles then fined him a further $1,000. “Nobody likes to lose a thousand dollars,” Miranda told newsmen. “But maybe I can play real well this season and make Richards give me my money back.” In fact, the Orioles did rescind the fine, then and in other years when he reported late.

Willy also described how the Cuban civil strife was causing visa problems for everyone down to his dog and parakeet.47 Indeed, 10 days before the shortstop finally signed on March 23, an assassination attempt on dictator Fulgencio Batista set off a bloody wave of repression.

When Miranda signed that year, he said, “The rest of them will have to play with two gloves on to get my job.” However, the tradeoff between his defense and offense became even more difficult over the next couple of seasons. His at-bats declined from over 500 in 1955 and 1956 to 349 in ’57 (with a .194 average and .204 slugging percentage) and then 230 in ’58 (.201/.243). On July 30, 1958, Paul Richards said, upon pulling Willy for a pinch hitter, “You already have three hits and it defies logic to think you’re going to get four.”48

Bob Maisel wrote, “Richards. . .occasionally gets fed up with the idea of having an All-American out for a regular. He frequently replaces Willy at short in an attempt to get more punch in the Oriole attack, but invariably the experiment fails and the Little Cuban winds up back at his old stand.” Jim Brideweser wasn’t the answer and neither was Foster Castleman, while rookie Ron Hansen broke his hand early in the ’58 season. Willy Jr. said, “The Orioles always brought somebody up to try to take over the position. My father welcomed them, he understood. They really wanted Jim Brideweser, who was a nice guy, to take over. They really had high hopes.”

Richards also gave his “circus performer” a pet name. The skipper said in 1957, “We win on defense and we’re just kidding ourselves when we don’t have ‘Ringling Brothers’ in there.”49 The year before, he called Miranda “Barnum and Bailey” instead.50 Willy had quick hands (Richards called them “the hands of a pickpocket”) and a strong arm (teammate Gus Triandos called it “almost abnormal for such a small guy”).51 He also augmented his range with study and smart positioning. “He was as intelligent as he was good with the glove,” said fellow Cuban and friendly rival Pedro Ramos. “He knew all his opponents perfectly. . .it helped him get to balls no other shortstop would ever have caught.”52

Willy brought further subtlety to his play. He would actually miss balls on purpose while taking infield practice—the better to recover from bad hops in real games.53 Also, “once asked why so many of his throws to first baseman Bob Boyd were in the dirt, Miranda said, ‘That’s only in the late innings when the sun sets over the corner of the left-field fence. If I throw the ball up, Boyd has trouble seeing it. But if I one-hop the ball, then he doesn’t have to contend with the sun.’”54

In 1958-59, Miranda’s last full winter with Almendares, he was a league all-star for the last time (.247-1-15). He also won his final Cuban championship and appeared in one more Caribbean Series that February. In Caracas Willy batted .316 (6 for 19, including a triple) as the Alacranes won the tournament, taking five out of six games.

On January 5, 1959, news service photos showed Willy chatting with two of Fidel Castro’s soldiers at the Havana airport while he awaited transportation to the United States. Just four days before, the revolutionary forces had ousted Batista. Commissioner of Baseball Ford Frick advised American clubs that they could recall major- and minor-league ballplayers, but as it turned out, the Cuban League shut down for only five days and the players stayed put.

The 1959 season was Miranda’s last in the majors. The previous October, Baltimore had obtained old teammate Chico Carrasquel from Kansas City. Willy also reported 35 days late to camp; Paul Richards levied two more stiff fines ($1,000 total out of a $9,000 salary) and later suspended him until he “got in playing shape.” Miranda had been perennially late in the past, citing the time-honored excuse of “visa problems.” This time he noted simply “personal problems,”55 but in reality he never cared for spring training. Since he always played winter ball, he considered that he was already in condition. Willy Jr. added, “My father didn’t have problems with Castro because he was non-political.”

As a result, Willy got just 96 at-bats in 65 games, hitting a feeble .159. He appeared just twice in the entire last month of the season, in a doubleheader versus Washington on September 7. Following the season, Baltimore sent him outright to Miami in the International League. Yet, as Richards said in 1975, “In the years we were trying to build a team in Baltimore, the fans didn’t have much to entertain them. From 1955 to 1959, Miranda kept the interest alive. I always felt, in some ways, he helped save the franchise in those formative years.”

Miranda’s Cuban career ended on a somewhat odd note that winter, as he went to the Havana Reds in the middle of the season. In a way it was a compliment, as old friend Fermín Guerra was managing the Reds and traded for him, but Willy’s heart was always with Almendares, Havana’s eternal rival. Willy Jr. said, “It was all about money and publicity.”

Miranda finished his 12 seasons in Cuban ball with a batting average of .236 on 523 hits in 2,214 at-bats. He had 3 homers and 145 RBIs, but showed a little more extra-base pop with 57 doubles and 26 triples. Even though he ran well, Willy was never much of a base stealer. He stole 15 during his Cuban career and 13 in the majors. Oddly enough, though, he stole home twice in one game for Almendares in 1958.

Miranda, who in many respects was a private man operating on his own, made a secret decision in 1960: to leave Cuba. “He planned leaving without even telling my mother,” said Willy Jr. “We got out so easily because we took out the same things we always did. We would load up the trailer, take the ferry to Key West, and then my father’s old friend Mario ‘El Mulato’ would drive us and Ali our dog up to Baltimore. My father would come up later.” This time was different, though, because the Castro regime was watching closely. “He got on a Pan Am flight by himself under another name, thanks to friends.”

In March 1960, Willy joined the Los Angeles Dodgers organization. Baltimore sent him and future Detroit Tigers general manager Bill Lajoie to L.A., completing the deal in which they had received Jim Gentile the previous October. Miranda spent the 1960 season with the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in St. Paul. He then played his final year as a pro with the Syracuse Chiefs in 1961. Triple-A ball returned to Syracuse for the first time since 1955 that year, and the revived franchise signed Willy in February. The parent club was the Minnesota Twins, newly moved from Washington. Their starting shortstop was Zoilo Versalles, who had idolized Willy as a boy growing up in Cuba.56

Although he received several offers to coach, including one from the New York Mets in their first season,57 Miranda retired to Baltimore, where he made his home after leaving Cuba. Willy Jr. recalled, “One of the things that hurt him was that the Orioles never gave him an opportunity” to stay in their organization.

As of 1964, Miranda was the chairman of “Bird’s Nest 954,” an Orioles fan club—in the Maryland State Penitentiary. The group sponsored a Little League team in nearby Pimlico, buying the children uniforms and equipment from their own small earnings. They also promoted baseball and softball within the prison, with Willy’s help from the outside. He gave the inmates pointers.58 59 “It was a way of staying in touch with the game,” said Willy Jr.

Willy and Amada were divorced in 1966. In 1967, he married Agnes Maria Caruso. They would have one child together, a son named Marco Antonio.

Miranda returned to pro ball in 1968, managing the Monterrey Sultanes in the Mexican League. He got the job through one of his old connections, Beto Ávila, the former Indians star known as “Bobby” in the United States. Willy only lasted until May 22, though; “the club’s front office merely said, ‘The Sultans aren’t winning with Miranda as manager.’”60 Despite the potent batting of local great Héctor Espino, they finished in last place because of weak pitching.61 “It was a mess, he never should have gone,” Willy Jr. said. “The Mexican fans were horrible.”

In 1969 Miranda took a look—and passed—on an opportunity in the short-lived and shady Global League. Willy Jr. recalled, “They were really hard up for players.” The next year, Willy Jr. went to the NCAA College World Series with the University of Delaware. He has since remained in The First State, which has honored him for his many years of service as a high-school teacher and coach.

Willy Sr. had one more brief go-around in the pros in 1979, as he managed the Panama Banqueros in the short-lived Inter-American League. Panamanian Chico Salmón started the season as manager, but he was fired in mid-May with the league’s worst record, 3-13.62 The club folded on June 17, at the season’s halfway point, with a 15-36 record. The rest of the league followed 13 days later. “I think he went as a favor to Bobby Maduro [the Cuban entrepreneur who launched the IAL],” said Willy Jr. “They called him in. He wasn’t there to start the season.”

That year Miranda also enjoyed a personal honor, as the Federation of Cuban Ballplayers in Exile named him to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame. He entered along with his fellow shortstop Leo Cárdenas.

Outside of baseball, Miranda pursued various occupations following his playing days. As of 1975, he was a sales and service representative for the Dixie Saw Company. He also owned an apartment building and two houses in Baltimore. His wife ran a beauty parlor that bore his name. One remarkable event took place in June 1976, when Willy was working for an industrial tool firm. A fire broke out in a machine shop across the street and Miranda dashed into the blaze to rescue the proprietor, suffering smoke inhalation. Baltimore made him an honorary fireman and gave him the Distinguished Civilian Award for his heroism. Said Mayor William Donald Schaefer, “A man is judged by how he reacts under stress. Willy made the big play and saved another man’s life.”63 “With characteristic modesty, Mr. Miranda said, ‘What I did was as simple as catching a ground ball and throwing it to first base.’”64

In addition, Miranda worked as a car salesman and, for the last 10 years of his working life, as a security officer at the Baltimore Convention Center. He retired for good in 1994.

Willy never forgot his roots. “So many things I miss about [Cuba],” he told Milton Richman in 1977. “I miss the sky at night. When you look up, you see all is blue and so full of stars. I miss the palm trees, the beautiful weather and the nightlife. But I am an American citizen now and I have to kiss this country because it is my house. I have to protect and thank the United States, always, and the best way for me to do that is by being as good a citizen as I can possibly be.”65

Cult author Barry Gifford (Wild at Heart), then a young Cubs fan, also captured this feeling in his bittersweet account of a chance meeting with the Cuban. It was November 1976, and the scene was a Chicago bar. Willy was down on his luck at the time, having lost a job as a restaurant greeter (Gifford wrote that it was a Playboy Club). Even so, he remained chatty and cheerful. . .mostly. As they shared a drink and talked baseball, Miranda said, “Castro ruin Cuba. Ain nothin’ there for people now. . .Sure, Cubans the best ballplayers! But they ain nothin’ there. No money, no decen’ life.”66

Willy sent as much money as he could spare back to Cuba. “He never made much, and what he had, he gave away,” said Willy Jr. “He supported a lot of family, his and his wife’s.” His mother would use her special pet nickname for him (“Gori”) in correspondence because Castro’s secret police were reading people’s mail.

Miranda felt so strongly, in fact, that in 1980, he made a journey to help with the Mariel boat lift. He quit his construction job and borrowed $8,000 from friends to charter a fishing boat; Fausto Miranda also put up money. Their brother Raúl was sick; their sister Chicha needed an operation but couldn’t get it. Their sister Aïda and her daughter Mayda became part of the plan, too—as did many other fellow Cubans to whom Willy simply could not say no.

“Disguising his identity with a beard and dark glasses because Cuban officials were unhappy with his defection, he jammed 22 people in a boat that was only capable of handling 19. At night, the boat started to sink in the middle of the Florida Straits and it was only the arrival of a U.S. Coast Guard cutter that saved their lives.”67 The Sporting News called it “Miranda’s Miraculous Mission.”68 Willy Jr. said modestly, “You took who they gave you. Other boats did the same thing.”

Willy Miranda passed away on September 7, 1996 from lung cancer, though the immediate cause was heart failure. Some obituaries—including the front-page story in El Nuevo Herald—also cited pulmonary emphysema. Ever since the fire rescue 20 years before, his lungs had affected his health.69

Some 200 people attended Miranda’s funeral Mass at St. Anthony of Padua Church in Hamilton, Maryland, where he was a communicant. His Catholic faith remained important to Willy throughout his life. There were seven speakers at the Mass, including the five Miranda children. He is buried in Baltimore’s Gardens of Faith Cemetery.

“I be all ri’, everybody remember Willie Miranda,” said the shortstop to Barry Gifford in 1976.70 The next year, as White Sox owner Bill Veeck celebrated the club’s unsung heroes, another Chicago writer, Bob Logan in the Chicago Tribune, also refreshed fans’ memories. Logan’s article led off by emphasizing, “The way Willie Miranda played it, baseball was fun.”71

With the passage of time and the absence of video, however, it has grown more difficult to conjure up images of Miranda’s magic at short. Yet we can take it on faith from his peers. One of those men is another survivor of pre-Castro Cuban ball: Tony Taylor, Willy’s double-play partner with Almendares in the late ’50s. “To me, Willy Miranda was the best shortstop I ever saw. The way he moved to field a ball, there were no bad hops with Willy Miranda. This guy was unbelievable.”72

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Willy Miranda Jr. and the Miranda family for their assistance, and also to Conrado Marrero for his memories. Thanks also to SABR member Kit Krieger and Rogelio Marrero for helping to obtain Marrero’s input.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet, probaseballarchive.com, and checkoutmycards.com, as well as:

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Notes

1 “Willie Miranda, 70, Shortstop in Majors,” New York Times, September 9, 1996.

2 John F. Steadman, “The Secret of Willie Miranda’s Glove,” Baseball Digest, December 1975: 64.

3 Tom Boswell, “The Wizard: The Land of Oz” in The Heart of the Order (New York: Doubleday, 1989).

4 Career OPS+ statistics, as calculated by baseball-reference.com: Mendoza 41, Miranda 55, Ordóñez 59. Author Stephen M. Lombardi, in his book The Baseball Same Game, offers another recent comparison: utilityman Mike Benjamin. This parallel is based on hitting, though; Benjamin was a very good fielder but not in Miranda’s class. Another author, Jim Lebuffe, called Mendoza and Miranda “cousins” in Parallel Hitters.

5 Peter C. Bjarkman, Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 41.

6 Rogerio Manzano, “Magos dentro del campo.” Cubaencuentro.com, October 23, 2002.

7 Javier Mota, “Muere Willy Miranda, Una Gloria Del Béisbol Cubano.” El Nuevo Herald (Miami, Florida), September 8, 1996: 1A.

8 Source: Willy Miranda, Jr., who uses the same spelling.

9 Steadman, op. cit.

10 Ángel Torres, “Willie Miranda y El Guante Que Salvó Una Franquicia.” http://www.amigospais-guaracabuya.org/oagat005.php.

11 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards (New York: Contemporary Books, 2001), 33.

12 Mota, op. cit.

13 Torres, op. cit. After Castro took power, he expropriated the school, which would become the infamous Villa Marista prison.

14 Francisco José Moreno, Before Fidel: The Cuba I Remember (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2007). 57.

15 Bjarkman, op. cit., 470.

16 Bill Thompson. “Speaking of Sports,” The Paris News (Paris, Texas), May 17, 1948: 2.

17 Ibid., 11.

18 Bob Maisel, “True to His First Glove,” Baseball Digest, December 1957: 7-9.

19 Ibid.

20 Steadman, op. cit.

21 Ralph Roden, Associated Press, “‘Good Field, No Hit’ Tab Fits Much of Major League Talent,” March 4, 1951.

22 Bill Roundy, “Roundy Says…” Wisconsin State Journal, February 27, 1951: Section 2, page 4.

23 Marshall Smith, “The Senators’ Slow-Ball Senor,” Life, June 11, 1951: 92.

24 Until the end of his career, nearly all of Willy’s baseball cards showed 1928 as the year of his birth and newspaper stories worked with this date. His 1955 Bowman and 1958 Topps cards did show 1926.

25 Ed Sainsbury, United Press International, “Proposed Williams-For-Carrasquel Deal Gets Emphatic Veto From Chisox,” November 7, 1951.

26 Harry Grayson, “Carrasquel Option Makes Joke of Disability Law for Veterans,” Newspaper Enterprise Association, July 9, 1952.

27 Dan Daniel, “Greenberg’s Waiver Protest Attacks Trade the Wrong Way,” New York Telegram, August 5, 1952.

28 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck — As in Wreck (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 141.

29 United Press International, “Miranda Has Last Laugh,” June 17, 1953.

30 Ibid.

31 John Griffin, “Sportrait for Today,” Coshocton (Ohio) Tribune, June 25, 1953: 17.

32 William Gildea, “Making the Case for the Defense,” Washington Post, March 29, 2002: H3. This is a deduction, since the switch-hitter’s only other homer at Yankee Stadium, on July 19, 1954, was a solid line shot into the left-field seats off lefty Ted Gray.

33 Milt Richman, United Press International, “Willie Miranda,” April 20, 1977.

34 Associated Press, “Miranda Shot by Young Son,” October 14, 1953. See also: “Yanks’ Miranda Wounded,” New York Times, October 11, 1953: S3.

35 Jorge Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005), 380.

36 Mota, op. cit.

37 David Condon, “Minnie Minoso: Cuban Comet,” Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1960: F14.

38 Fred Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 244. (Originally published in 1955.)

39 Milton Richman, Associated Press, “Ex-Yank Miranda, Sick With Fever and Sick at Heart, Gains Revenge,” April 21, 1955.

40 Ibid.

41 Michael Hilton, “Going for It — and Failing,” Harvard, Volume 91, 1988: 14.

42 Associated Press, “Miranda Gets Big Raise,” December 18, 1955.

43 Associated Press, “Willie Miranda Advised To Quit Winter Baseball,” January 18, 1956.

44 Associated Press, “Willie Miranda Still Pet Of Baltimore Fans,” August 28, 1956.

45 Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder: The Bonus Rule of 1953-1957 (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1996), 73.

46 John Eisenberg, “Gastall’s secret, fatal flight,” Baltimore Sun, September 16, 2006.

47 Associated Press, “Orioles Sign Holdout Miranda, Fine Him $1,000 For Holding Out,”, March 15, 1957.

48 Fred Rasmussen, “Willy Miranda, 70, was Orioles shortstop,” Baltimore Sun, September 8, 1996: 4C.

49 Maisel, op. cit.: 8.

50 “Willie Miranda Still Pet Of Baltimore Fans”

51 Rasmussen, op. cit.

52 Mota, op. cit. Oddly enough, Nellie Fox stated in 1960, “Willie Miranda was an outstanding fielder, but he had trouble with balls hit straight at him.” Harry Grayson, “Harry Grayson’s Scoreboard,” Newspaper Enterprise Association, July 29, 1960.

53 Steadman, op. cit.

54 “Miranda lauded as Houdini at short,” Baltimore Sun, September 11, 1996: 3D.

55 Associated Press, “Miranda Reinstated,” April 14, 1959.

56 James P. Terzian, The Kid From Cuba: Zoilo Versalles (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1967), 14-15, 74.

57 Mota, op. cit.

58 Associated Press, Gordon Beard, “Little League Team To Play ‘In Prison,’” March 13, 1964.

59 Associated Press, Gordon Beard, “Reds Have Captive Crowd,” July 1, 1964.

60 Roberto Hernandez, “Sultans Fire Miranda,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1968: 38.

61 Horacio Ibarra, Héctor Espino: un hombre, un bat, una leyenda! (Monterrey, Mexico: Sociedad Cuauhtémoc y Famosa, 2001), 98-99.

62 The Sporting News, June 16, 1979: 45.

63 Associated Press, “Willie Miranda honored,” June 17, 1976.

64 Richman, “Willie Miranda.” See also Rasmussen, op. cit.

65 Richman, “Willie Miranda.”

66 Barry Gifford, “Willie Miranda.” Originally published in Baseball, I Gave You All the Best Years of My Life (Kevin Kerrane and Richard Grossinger, eds.) (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1977), 132-33. See also Barry Gifford, The Neighborhood of Baseball (New York: Dutton, 1981), 145-147.

67 Rasmussen, op. cit.

68 Bob McCoy, “Miranda’s Miraculous Mission,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1980: 6.

69 Mota, op. cit. See also “Willy Miranda Muy Grave en Baltimore,” El Nuevo Herald, March 19, 1988: 7B.

70 Gifford, op. cit.

71 Bob Logan, “Miranda: Unsung and well-traveled,” Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1977: E3.

72 The source for this particular quote is unknown, but Taylor expressed the same basic opinion in 2001 as a coach with the Florida Marlins. “Incansable Trabajador de Los Peces,” El Nuevo Herald, September 3, 2001: 9C.

Full Name

Guillermo Miranda Perez

Born

May 24, 1926 at Velasco, (Cuba)

Died

September 7, 1996 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.