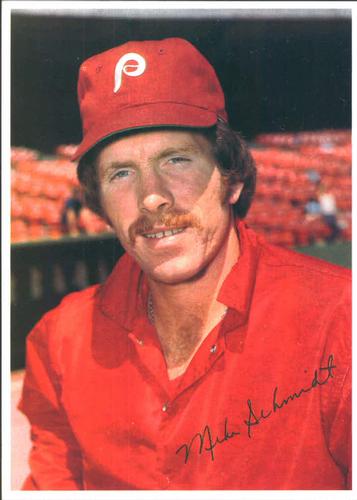

Mike Schmidt

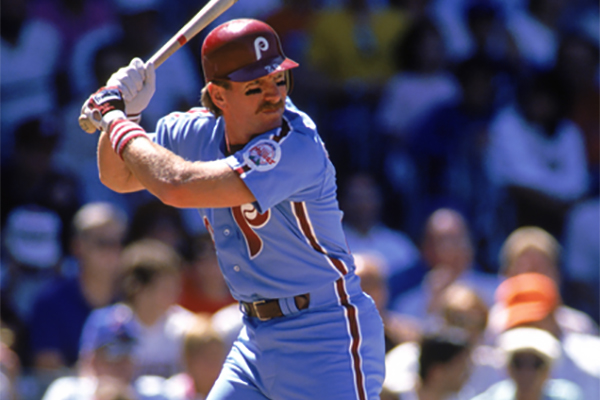

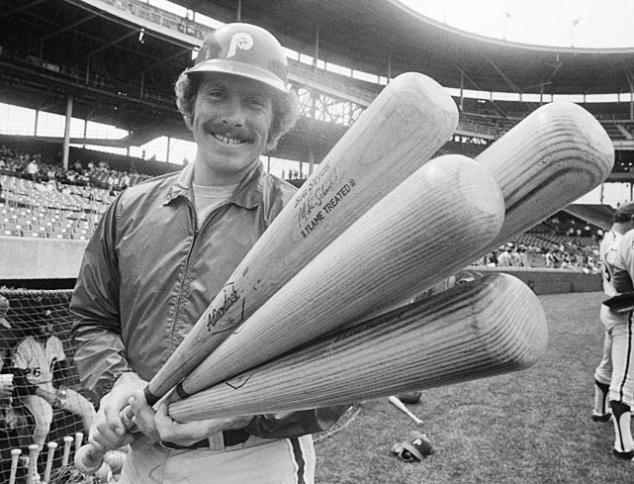

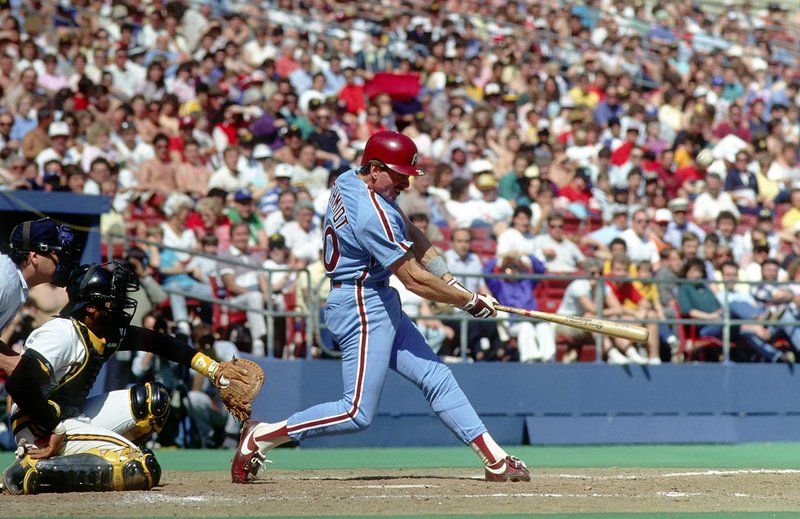

By the time Mike Schmidt retired early in the 1989 season, he was regarded as perhaps the greatest all-around third baseman in baseball history. No major-leaguer hit more homers during the 1980s, but he was not a one-dimensional threat: he curbed his tendency to strike out and stole bases when needed. In the field, he displayed great range, reflexes, arm, and daring. He charged bunts to make barehanded plays, nipping runners at first with submarine throws from somewhere between third base, the pitcher’s mound, and home plate. He also frequently barehanded high choppers off the artificial turf at Veterans Stadium, snagging the ball and firing in one smooth motion to get the out.

At the time of his retirement, Schmidt ranked seventh on MLB’s all-time home run list and was a three-time National League MVP, 12-time All-Star, and 10-time Gold Glove Award winner. Five years after his retirement, Schmidt was elected to the Hall of Fame.

Michael Jack Schmidt was born in Dayton, Ohio, on September 27, 1949, to Lois (Philipps) and Jack “Smitty” Schmidt1. Mike’s parents were the owners and operators of Philipps Aquatic Club on the north side of Dayton, one of the longest-surviving operations of a series of aquatic clubs throughout Ohio that were founded in 1865 by Lois’s great-grandfather, Charles Philipps.2 The couple also operated Jack’s Drive-In on the grounds of the club at Leo and Keowee Streets, and the two businesses were popular family destinations in Dayton for generations. Mike’s older sister Sally and her husband operated the businesses until they closed in 2009.3 “The family business was swimming pools and ice cream,” recalled Schmidt in 2014.4

As a five-year-old, Schmidt climbed a tree in his backyard and, from a high branch, reached for a wire that turned out to have 4,000 volts of electricity running through it. Lois Schmidt told a reporter in 1974 that her son’s heart had stopped, and after his grip relaxed he fell down through the tree with branches slowing his fall, “hit[ting] the ground hard enough to start his heart going.” He was fortunate enough to survive with just burn marks on his legs.5

Always an excellent athlete, “Schmitty”6 was a three-sport star at Dayton’s Fairview High School (playing youth sports against long-time Dodgers catcher Steve Yeager7, whom Schmidt later described as then being “the greatest athlete I ever saw”8) before two knee surgeries ended his participation in football and basketball.9 He was such a workaholic when it came to baseball at Fairview that his girlfriend at the time would tell her mother that she was with Mike at the batting cages, and mom wouldn’t be worried about the two of them.10 Schmidt also enjoyed golfing at the Kittyhawk Golf Center in northeast Dayton, leading to a lifelong interest in the links.11 Although not heavily recruited as a baseball player after only hitting .179 with one home run as a switch-hitting senior, he made the freshman team at Ohio University as a walk-on shortstop but hit only .260 with one homer.

The summer after his freshman year was pivotal for Schmidt. Playing for Parkmoor Restaurant in Dayton’s National Amateur Baseball Federation Summer League, he started at shortstop, gained confidence, and improved greatly over the summer. Of his 13 hits in the short season for Parkmoor, six were homers (leading the league), two were doubles, and he added a triple.12 Back at OU, at the suggestion of his coach, Bob Wren, Schmidt stopped switch-hitting to focus on batting right-handed. Wren, known as one of the finest college coaches of his era, also got Schmidt to build up his leg strength.13 The improvement in Schmidt’s game was immediately noticeable. As a sophomore, he hit .312 with seven home runs, and as a junior and senior did even better, batting .333 and .331, respectively, with 10 homers each year, being named as an All-American both years as well.14 The two 10-homer performance tied the Ohio Bobcat single-season record.15

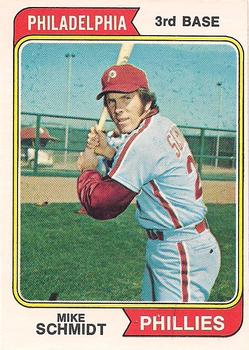

Schmidt’s potential impressed legendary Phillies scout Tony Lucadello, who had followed him since high school. Lucadello wanted to draft Schmidt with the Phillies’ first pick in the 1971 draft, and when Schmidt was available in the second round (30th overall), the Phillies selected him one pick after the Royals selected George Brett.16 He signed for $32,500, bought a Corvette Stingray, and reported to Philadelphia.17

Schmidt’s professional career for the Phillies began with an exhibition game against the AA Reading Phillies in Reading, Pennsylvania, on June 17, 1971. Starting at shortstop for Philadelphia, he hit a game-winning home run against Reading.18 Although the Phillies had planned to start Schmidt in Class A, they instead assigned him to Reading. His transition to professional baseball was difficult. In 74 games with Reading, he struggled to adapt to professional pitching, batting only .211 with eight home runs and striking out 66 times in 268 at bats.19

Nonetheless, the Phillies promoted Schmidt to the AAA Eugene Emeralds for 1972. It was a breakthrough season, as he batted .291 with 26 home runs in 131 games. To take some of the pressure off Schmidt and allow him to concentrate on improving his hitting and reducing his strikeouts, manager Andy Seminick moved him to second base.20 Years later, Schmidt still fondly remembered two eight-day road trips to play the Hawaii Islanders, telling an interviewer, “That was one of the cool things about that year.”21

Despite a knee injury, Schmidt was promoted to Philadelphia as a September call-up. Although Steve Carlton was on his way to a Cy Young Award, the 1972 Phillies were the worst team in the NL. Eliminated from contention, they decided to evaluate Schmidt at the major league level. Wearing uniform number 22 — he would switch to his iconic number 20 the next season — Schmidt struggled with 15 strikeouts in 40 plate appearances, playing mostly at third base for manager Paul Owens.22 He did manage to hit his first career home run in the majors, a three-run blast off Balor Moore (after Moore intentionally walked Roger Freed with two outs and a man on third to pitch to the then unknown Schmidt) on September 16 that led to a 3-1 win over the Expos.23

Following the 1972 season, Owens returned to his GM role, and the Phillies hired Danny Ozark as manager.24 Ozark had developed prospects in the Dodgers organization and was hired to bring along the young roster, including Schmidt, Larry Bowa, Greg Luzinski, and Bob Boone.25 Schmidt was playing for the Caguas Criollos in the Puerto Rican winter league when the Phillies traded Don Money, clearing an opening for him at third base, although he still needed to beat out Cesar Tovar and others.26

Schmidt’s 1973 season got off to a slow start when he missed the first ten games with a dislocated shoulder. Relatively inexperienced with only a season and a half in the minors, he struck out too often (136 strikeouts in 367 at bats) and hit only .196 for the season. Owens and farm director Dallas Green wanted to return Schmidt to the minor leagues, but manager Ozark saw potential and wanted to allow him the opportunity to learn at the major league level. While Schmidt showed glimpses of his power potential (18 home runs, including a walk-off shot against Bob Gibson in April), highlights were few and far between in 1973.

Ozark’s frequent hitting suggestions affected Schmidt’s already fragile confidence, and his rookie year ended in an 0-for-26 slump.27 After the season, Schmidt returned to Caguas, this time managed by Phillies coach Bobby Wine, who told Schmidt not to swing so hard and let his natural talent take over. That tip and the encouraging feedback helped Schmidt recover his confidence and turn his career around. Swinging easily, Schmidt realized he could hit the ball just as far.28

Following his newfound winter ball success, Schmidt arrived confident for 1974 spring training — and as a newly married man, having wed his girlfriend Donna Wightman right before leaving Ohio. Once again, Ozark tried to change Schmidt’s approach, suggesting that he use a stance like Nate Colbert of the Padres. After trying it, Schmidt refused to make the change, preferring to return to the minors before changing the style that had worked over the winter. Having seen those results, coach Wine also argued on behalf of Schmidt, and Ozark relented.29 Schmidt’s decision to stick with what had worked was well placed. He arrived as a force in the major leagues in the 1974 season. Newly acquired second baseman Dave Cash coined the slogan “Yes we can!” for the Phillies, but he was also particularly encouraging to Schmidt, who started to believe that lofty goals such as 100 runs batted in were possible.30

On June 10, 1974, Schmidt made national headlines by hitting one of the most notable singles in baseball history. In the Astrodome, Schmidt hit what appeared to be a no-doubt-about-it home run, only to see it land in shallow center field. The would-be home run drive had hit a loudspeaker hanging from the roof, 117 feet off the ground. After the game, Schmidt told a reporter, “I said to myself, ‘That damn speaker cost me a homer.’ If for some reason late in the season I’m one short [of the home run lead], I’ll think back about it.”31 The next day, the speaker was raised by 56 feet.32

On June 10, 1974, Schmidt made national headlines by hitting one of the most notable singles in baseball history. In the Astrodome, Schmidt hit what appeared to be a no-doubt-about-it home run, only to see it land in shallow center field. The would-be home run drive had hit a loudspeaker hanging from the roof, 117 feet off the ground. After the game, Schmidt told a reporter, “I said to myself, ‘That damn speaker cost me a homer.’ If for some reason late in the season I’m one short [of the home run lead], I’ll think back about it.”31 The next day, the speaker was raised by 56 feet.32

Schmidt was selected as a reserve for the All-Star Game, the new slugger having not even been listed on the fan ballot for consideration as a starter. While still striking out 138 times in 1974, he led the majors in home runs with 36, finished second in the NL in RBIs with 116, and batted .282. He was also the NL Gold Glove runner up to Doug Rader and finished sixth in NL MVP voting. Using current advanced metrics, Schmidt led the majors in wins above replacement (WAR) at 9.7, a full win above the next highest player, and his career peak in that statistic.33 At the same time, the Phillies finished at 80-82, a nine-win improvement from the previous season.34

In 1975, another mentor arrived when the Phillies signed Dick Allen. Well aware of Philadelphia fan pressure from his prior stint with the team in the ’60s, Allen joked with Schmidt and told him not to put so much pressure on himself. Schmidt again led the league in home runs with 38 (his first of three straight seasons at that figure) and the Phillies finished second in the division at 86-76, but it was a frustrating season. Schmidt struck out a league-leading 180 times (a career high), and his average dropped 33 points to .249. Bothered by the perceived lack of results and frequent boos from the fans, he again tinkered with his batting stance. He even tried transcendental meditation (as a number of other Phillies had also tried) before realizing that it was not helpful.35

The Phillies won 101 games in 1976 and reached the postseason for the first time since 1950. Schmidt hit 12 home runs in the first 15 games, including four consecutive home runs in an April 17 game in Chicago (then just the fourth player in MLB history to do so). The Phillies had fallen behind, 12-1, early in the game, but powered by Schmidt’s homers — the fourth in the tenth inning, they won, 18-16.36 Schmidt recalled in 2020, “I don’t think too many guys have hit four in a row. But, truthfully, there isn’t a lot of tension in an at-bat when you’ve already hit three! Got a pretty good day going here, you know? Sports Illustrated put me on the cover for the first time. You kidding me? The cover of SI? Back then? Wow.”37

The Phillies caught fire after that big comeback victory, going 55-22 from that point through the All-Star break. Philadelphia hosted the Bicentennial All-Star Game, and Schmidt was joined by teammates Boone, Bowa, Cash, and Luzinski on the NL All-Star team. When they clinched the division in Montreal on September 26, a possible rift in the clubhouse emerged. Schmidt joined Allen, Cash, and Garry Maddox for a separate celebration from the rest of the team, a fact to which Tug McGraw called attention. Schmidt noted, “It happened that my best friends on the Phillies were Black. I feel guys become friends because they have similar interests. And I’ve learned a lot from Garry and Dick. Tug brought it up, but it’s dead now. It wasn’t a good scene. But it’s over.”38

The season ended on a disappointing note as they were swept by Cincinnati in three games in the NLCS. Schmidt was solid in the series, batting .308 with two doubles and two RBIs, but it was not enough to beat the Reds.39 The year was a successful one for Schmidt. He again led the NL in home runs, finished third in NL MVP voting, and won his first Gold Glove, cutting his strikeouts and increasing his batting average. Following the 1976 season, Schmidt signed a six-year deal worth $565,000 per season to keep him in Phillies pinstripes.40

Schmidt got off to a torrid start in 1977 with 26 home runs by the All-Star break. His first half stats could have been even better had it not been for an incident in Pittsburgh on July 8. After being hit in the ribs by Bruce Kison, his second hit-by-pitch in four days, Schmidt took a few steps toward the mound. Kison challenged Schmidt to a fight, and Schmidt accepted. Ed Ott tackled Schmidt, fracturing Schmidt’s finger in the fray. 41 While he continued to play well in the second half of the season (leading to his second Gold Glove), the broken finger hampered Schmidt’s ability to swing the bat. For the first time since 1973, he did not lead the NL in home runs, but he did lead all NL position players in WAR.42 The Phillies again lost the NLCS, this time to the Dodgers.

Following two straight NL East crowns, the Phillies returned largely the same team for the 1978 season. Ozark named Schmidt team captain in spring training. He accepted the honor, but also pointed out, “It makes no difference at all being captain. It’s no big deal. There’s nothing my being captain can do to a ball game.”43 The captaincy may have brought with it some added pressure. Noting that Schmidt struck out in his first at bat of the 1978 season, one writer opined, “It is suspected in some circles that Schmitty gets a gang of those homers in 11-3 wins. After all, he was 1 for 16 in last year’s playoffs.”44

He got off to another strong start before hitting a string of injuries, leading to a prolonged slump and his first disappointing season since his rookie year. For the first time since 1975, he did not make the All-Star team. He had faced the ire of the Philadelphia fan base his entire career, but 1978 was particularly difficult. Yet Ozark noted, “The fans are trying to stimulate Mike. They figure maybe he’ll get mad and hit better. I don’t think they’re saying he’s no good.”45 He ended up with his lowest home run and RBI totals since 1973. Nonetheless, he was the NL’s second most valuable position player by WAR and won a third straight Gold Glove.

The Phillies again won their division and faced the Dodgers in a rematch of the 1977 NLCS, which Los Angeles again won in four games. The Phillies were proving themselves to be a great regular season team that could not win in the postseason, and Schmidt was viewed as one of the reasons. Following the series, shortstop Bowa thought that the pressure was getting to the team, saying, “I think that at home the players want to impress the fans so much that we’re not as relaxed as we should be. I know Mike Schmidt isn’t relaxed.” Turning to Schmidt’s sizable contract, Bowa added, “Remember the Phillies offered him the money; he didn’t put a gun to their head.”46

The pressure was on for the Phillies to overcome the NLCS hurdle. On December 5, 1978, they signed Pete Rose (who’d been a third baseman since early 1975) to be the final piece to a championship puzzle.47 They toyed with the idea of moving Schmidt to second, but Rose moved to first base and showed a strong interest in Schmidt from the start. Comparing him to former teammate Joe Morgan, Rose thought Schmidt could be the best player in baseball. Rose also took some pressure off by commanding much of the media’s attention. Like Dick Allen before him, Rose sought to get Schmidt to relax and have fun playing baseball, nicknamed him “Herbie Lee” and constantly reminded him how great he could be.48 Schmidt later wrote that “It’s unbelievable that in 1979 Pete joined the Phillies. The player I wanted so much to be like as a kid was now my teammate, friend and mentor.”49

Following his tenth-inning game-winning home run in a May 17, 1979 23-22 slugfest at Wrigley Field (mirroring 1976’s 18-16 Phillies win), the Phillies raced to the top of the NL East. After that game, Schmidt commented, “Ballplayers often will say that you never can get enough runs to win in this park, but they always say it sarcastically. After today, they can forget the sarcasm.”50

In July, following a stretch of 12 home runs in 18 games, Schmidt was ahead of Roger Maris’s season record pace as he and Dave Kingman battled for the NL home run lead. While wondering how long he could keep up the pace, Schmidt commented, “I don’t think it’s humanly possible to be any better hitter than I’ve been for the last month.”51 Although Schmidt ultimately fell short of both Maris’s record and Kingman’s total, he wound up with 45 home runs, his career high to that point, and won his fourth Gold Glove. However, plagued by a slew of injuries, the Phillies stumbled to finish just 84-78, in fourth place in the NL East. On August 31, the club fired long-time manager Ozark and replaced him with minor league director Dallas Green.52

Everything came together for Schmidt and the Phillies in 1980. As Schmidt told The New Yorker 40 years later, “When I look back, nothing tops 1980. I hit .300 most of that year.53 I got a hundred and fifty-seven hits, and forty-eight home runs, which I believe are career highs. My first M.V.P. award. We got our World Series ring. I won the M.V.P. of the Series. That was a storybook season.”54

The season started strong for the team and its third baseman. In May, Schmidt hit 12 homers, powering the Phillies to a 17-9 record, and moving them to within a game of the first-place Pirates. However, battling a pulled muscle that caused him to miss the All-Star Game, he slumped in June and July and the Phillies drifted to three games out on August 1, then picked up the pace in August as the Phillies climbed to just a half-game back. With the division title on the line, Schmidt had a great stretch run from September 1 through October 4 (.298/13/28), and the Phillies played well enough to force the race to a three-game winner-take-all series in Montreal. Schmidt homered and knocked in both Phillies runs in a 2-1 win in the first game and hit an 11th inning two-run home run in the second game to propel the Phillies back into the postseason.55 Said Schmidt, “I finally got the big hits when we needed them.”56

The 1980 NLCS is remembered as a classic series in which the Phillies and Astros battled into extra innings in the final four games of the five-game series. Schmidt’s postseason woes continued as he batted only .208, including just 1-for-6 against ace Nolan Ryan, whom Schmidt would call the toughest pitcher he ever faced.57 In the decisive Game Five, Schmidt struck out in both the eighth and tenth innings. He lamented, “All I had to do that last game in Houston was hit a grounder to short, and we would’ve won the game. So I looked at a third strike and walked back to the dugout.”58 Still, the Phillies ultimately won Game Five and were headed to the World Series for the first time in 30 years; Schmidt pointed out, “All the one-liners they’ve used about the Phillies, they can erase.”59

Schmidt more than redeemed himself in the World Series against the Kansas City Royals. He hit in every game, going 8 for 21, driving in seven runs and scoring six.60 In Game Six, his single in the third inning knocked in two runs, all that Carlton and McGraw would need, as the Phillies won, 4-1, to clinch the franchise’s first world championship.61 He recalled later, “We were the kind of team that wouldn’t die.”62

In the chaos of the post-game locker room, Schmidt received a bizarre gift from his opposing third baseman, who famously suffered from a case of hemorrhoids during the Fall Classic. As reported in the Philadelphia Daily News, “[A] reporter from a New York newspaper forced his way through the congestion [and] delivered to Schmidt a basket of fruit and candies, then whispered in Mike’s ear. ‘You’re kidding,’ Mike Schmidt said. The basket had been sent by George Brett. ‘George said to tell you it will help your hemorrhoids,’ the guy pointed out.”63

Schmidt’s grandmother Viola Schmidt had died on September 26, and while he celebrated with his teammates, he kept her in mind. As the Philadelphia Inquirer reported the next day:

“She was the first person to throw a baseball to me,” Schmidt said. “That was the only prayer of mine that wasn’t answered down the stretch.” It should have been one of the happiest moments of his life, but Schmidt’s excitement was restrained. He was reflective, about his grandmother’s passing, his faith in God (“I play this game to glorify God, to tell you the truth”) and the image of the Phillies as a team that was uncommunicative, unlikable and one that couldn’t win the big ones. “I don’t think anyone would dislike me personally if they spent enough time with me,” Schmidt said.64

Schmidt later recalled, “We were kind of like that guy who can’t win a major in golf. Everybody is talking about you and thinking about you … 1980 erased all that sense of an inability to play under pressure. What a big anchor around our necks to be removed. It completed my career up to that point.”65

At the parade following the World Series, Schmidt provided an olive branch to the fan base that had booed him over the years, telling the gathering, “Take this world championship and savor it because you all deserve it!”66 (It was a less raunchy version of McGraw’s proclamation, “New York City can take their world championship and stick it, because we’re number one!”67) After the season, Schmidt was unanimously selected as the NL MVP, only the second unanimous winner; his 48 home runs had broken Eddie Mathews’s record for a third baseman.68

Expectations were high for 1981, as the Phillies brought back largely the same club except for Gary Matthews replacing long-time left fielder Luzinski. Both Schmidt and the Phillies got off to a strong start, and the team led the NL East by 1½ games when play was stopped by the strike on June 10. Schmidt was batting .284 with 14 homers and 41 RBIs. The All-Star Game on August 9 marked the return of baseball, and Schmidt’s two-run homer off Rollie Fingers gave the NL a 5-4 win, which he later described as his most memorable All-Star Game.69

Expectations were high for 1981, as the Phillies brought back largely the same club except for Gary Matthews replacing long-time left fielder Luzinski. Both Schmidt and the Phillies got off to a strong start, and the team led the NL East by 1½ games when play was stopped by the strike on June 10. Schmidt was batting .284 with 14 homers and 41 RBIs. The All-Star Game on August 9 marked the return of baseball, and Schmidt’s two-run homer off Rollie Fingers gave the NL a 5-4 win, which he later described as his most memorable All-Star Game.69

Assured of a playoff spot as first-half division champions, the Phillies sputtered once play resumed, but Schmidt played some of the best baseball of his career, hitting .356 with 17 homers and 50 RBIs in 50 games in the season’s second half. Following the regular season, the Phillies battled Montreal in the first-ever NLDS, which the Expos won in five games, Schmidt going 4-for-16 with one home run.70

While 1980 may have been a more satisfying year for Schmidt, he had performed even better in the strike-shortened 1981 season. His .316 batting average marked a career high, and his .435 OBP, 31 home runs, and 91 RBIs paced the NL. He received his sixth straight Gold Glove and repeated as NL MVP. Reflecting on his successes in 1980 and 1981, he credited Rose’s example and Green’s leadership, noting, “The two greatest years I’ve had as a player were under the management of Green… It was a pleasure to play for that man and his coaching staff.” 71

During the 1981-82 offseason, Green was replaced by Pat Corrales, and Schmidt signed a new six-year contract with the Phillies, guaranteeing him at least $10 million through 1987, then the second-largest contract in baseball history. Unfortunately, the 1982 season started poorly for Schmidt — a rib cage pull hampered him through June. He still had a solid season, but the Phillies finished 89-73, three games out.

The Phillies decided to take one more run at a championship, so for 1983 they picked up two legends: Joe Morgan and Tony Perez. Nicknamed the “Wheeze Kids” because of their age (after the 1950 Phillies “Whiz Kids”), the team’s Opening Day lineup included Rose, Morgan, Schmidt, Perez and Carlton.72 Despite high expectations, the season started off disappointingly, and with the team tied for first at 43-42, Corrales was fired as manager, with general manager Paul Owens taking over. Schmidt spoke out against the distractions of team management (Owens in particular) and in support of his teammates,73 and the team went on an 11-game winning streak in late September and clinched the division, finishing 90-72. Schmidt ended the regular season with his sixth NL home run title.

In the NLCS, they dispatched the Los Angeles Dodgers in four games behind Gary Matthews’s MVP performance and Steve Carlton’s two wins and 0.66 ERA. Schmidt also had a great series (.467 batting average and 1.329 OPS). The World Series was a different story, though. The “I-95 Series” against the favored Baltimore Orioles started with a Phillies win on the road, but the Orioles came back to win the next four. Matthews and Schmidt cooled down, with Schmidt going just 1-for-20. It was a disappointing ending to an otherwise successful season.

After the Series, the Phillies released Rose and Morgan and sold Perez. Schmidt was now the clear team leader. During the 1983 season, not only did he make the club’s Centennial Team, but he was named the “Greatest All-Time Phillies Player,” beating Carlton by over 5,000 fan votes. It was quite an honor for a soon-to-be 34-year-old player with years left in his career.74 In 1984, the Phillies began a stretch of disappointing seasons, and Schmidt would not be on a playoff team again. However, he served as a mentor to younger players and clearly led by example. He topped the NL again with 36 home runs (seventh time), 106 RBIs (third time), and a .919 OPS (fourth time).

Playing on Veterans Stadium’s notoriously rigid Astroturf field began to take its toll, so he sought out veteran athletic trainer Pat Croce, who put him on a workout regimen emphasizing cardiovascular and weight training, with a focus on flexibility, that he followed the rest of his career and beyond.75

Schmidt began 1985 poorly, so in late May, the Phillies called up top prospect Rick Schu to play third base. His streak of nine straight Gold Gloves at third notwithstanding, for the rest of the season Schmidt primarily played first base. The change obviously agreed with him, as his batting stats as a first baseman in 1985 were significantly better than those he had put up in his first two months playing third. Schmidt credited the improvement to a change he made in his hitting approach. Facing Dwight Gooden on August 12, after struggling to that point in the season, he decided, “What the heck, I’m gonna swing down on any pitch he throws me. Just like Dick Allen used to do.” The result, as he described it: “I tomahawked it, really chopped down. … When I looked up, the ball was on its way toward the right-center field scoreboard, about 450 feet away.”76

Schmidt continued to hit that way until he hurt his shoulder in 1988. From that game through 1987, his new approach resulted in a batting average of .297, compared to his prior career average of .265. Further, his strikeouts in 1986-87 fell below 100 for the first time (excluding the strike season), while keeping his OPS over .900 and home run total in the mid-30s. Schmidt described the difference: “After fifteen seasons, I finally felt like a great hitter, a really tough out. A good hitter, not just a dangerous hitter. There’s a difference.”77

The 1985 season was also notable for the “wig incident.” In an April interview with a Montreal writer, Schmidt was critical of Phillies fans, saying, “Whatever I’ve got in my career now, I would have had a great [deal] more if I’d played my whole career in Los Angeles or Chicago, you name a town—somewhere where they were just grateful to have me around.”78 He described the fans as a “mob scene,” “uncontrollable,” and even “beyond help.”79

The interview was published when the Phils returned to Montreal for the final series of June, with the choicest quotes quickly printed by the Philadelphia papers as well. Phillies fans, frustrated by their team’s plunge in the last season-and-a-half after so many successful seasons, were livid, and on July 1, when the 32-40, fifth-place Phillies returned to town, they let him have it, with loud boos and jeers during pregame drills. Schmidt went into the clubhouse, found a long crimson wig and dark Porsche sunglasses, and headed out to the field wearing them. He kept the “disguise” on through the pregame warmup.

The fans began to laugh and cheer, and as Gary Mathews put it, “Schmitty loosened up the whole ballpark. I thought he turned around what could have been a tense situation.”80 Although he struck out in the ninth inning with the tying run on base and received the customary boos, the big story was the wig, and fans seemed to begin to have a different feeling about him. Pictures of Schmidt in his wig appeared in virtually all local papers the next day.81

In his role as team leader, Schmidt had been conducting an unofficial “State of the Phillies” press conference at the beginning of spring training for several years. One local newspaper impertinently described it in 1986 as “infielder Mike Schmidt making his annual State of Mike Schmidt address.” That year, Schmidt stated he was ready for a move back to third base, and in fact he did, as Von Hayes took over first base.82

The 1986 Phillies had a mix of young and old on their roster, the latter led by Schmidt, age 36, and Carlton, age 41. However, the two greats would head in opposite directions that year. After 16 starts and a 6.18 ERA, Carlton was released, while Schmidt hit .290, with 37 home runs and 119 RBIs, to win his final NL home run and RBI titles to go with his final Gold Glove. After the season, he also won his third and final NL MVP award, tied for the most ever at that point. The Phillies finished with a winning record, but well behind the Mets. In a press conference after the season finale, Schmidt said he thought he would play just one more season and then retire to spend more time with his family, but he admitted he would consider playing longer if his knees held out and his family could deal with it.83

Schmidt entered the 1987 season with 495 home runs, at the time the 14th most in history. He had hit his 100th, 200th, 300th and 400th home runs on the road, and number 500 would be no different. On Saturday, April 18, with the Phillies trailing the Pirates, 6-5, in the 8th, Schmidt (sitting at 499) came to bat in the ninth with two on and two out. Don Robinson went to 3-0, then threw a fastball over the plate, perhaps expecting Schmidt to take a pitch, but Schmidt deposited it high over the left field wall. He slapped his hands together and did a little jig, circling the bases to enjoy not just his milestone but also having given the Phillies the lead.84 Meanwhile on the television broadcast, beloved Phillies announcer Harry Kalas shouted, “Swing and a long drive! There it is, number 500! The career 500th home run for Michael Jack Schmidt!”85 Schmidt hit his 500th home run in (to that point) the fourth fewest career at-bats, behind only Ruth, Killebrew and Mantle.

Overall, Schmidt had yet another excellent year, but with the team losing more than it won, late in the season, he expressed frustration with the Phillies organization, the stadium, and the minor-league system, and he considered entering free agency.86 However, he signed a new two-year contract, with only the first year guaranteed; the Phillies held an option for 1989. At his 1988 state of the team address, he said he would look to enjoy himself a bit more.87 Unfortunately, the Phillies finished in last place for the first time since Schmidt was a rookie. On a personal level, he dealt with nagging injuries, finally taking himself out of a game on August 12 because of a season-ending rotator cuff injury. His numbers in the Triple Crown categories were his lowest since his rookie season.

After having rotator cuff surgery, Schmidt hoped for a better 1989. However, the Phillies declined to exercise their option, instead offering less money than he expected. Thus, he chose to become a free agent for the first time in his career. Other than the Phillies, only the Dodgers, Yankees, and the Reds — then managed by Pete Rose — showed any interest in him. Preferring to end his career in Philadelphia, Schmidt signed a one-year contract with the Phillies.88

He slumped during the first two months of the 1989 season. On the day before Memorial Day in San Francisco, he misplayed an easy grounder that would have ended an inning, leading to four unearned runs scoring when the next batter hit a grand slam. Schmidt said later that moment was when he knew it was time to hang up his spikes. With a .203 batting average and just six homers and 28 RBIs in 42 games, he told teammates that he was going to retire.89 He flew with the team to San Diego and, before the May 29 game, made an official announcement. His speech became famous, especially his closing line, delivered amid tears: “Some 18 years ago, I left Dayton, Ohio, with two very bad knees and a dream to become a major league baseball player. I thank God that the dream came true.”90 At the time of his retirement, Schmidt led all active players in home runs, runs batted in, total bases, intentional walks and strikeouts. In July, fans voted him as the NL’s starting third baseman for the All-Star game. He appeared in uniform but chose not to play in the game.

In January 1990, The Sporting News named Mike Schmidt “Player of the Decade” for the 1980s.91 Many more accolades would follow, but no offers to remain in baseball. Schmidt was interested in becoming the Phillies manager or general manager, but the team had just hired a new GM, and the front office did not believe Schmidt would be a good hire in any capacity.92 To stay involved in baseball, he worked as an NLCS pre-game show host for CBS in 1989, his first broadcast work other than a short stretch in TV news during the 1981 strike. In 1990, he became a color commentator for the Phillies’ pay cable partner PRISM, working alongside former teammate Garry Maddox. He admitted he was not a great fit and chose not to return for the next season. In 1991, Schmidt was part of an unsuccessful group seeking to start up the new Florida Marlins franchise.93

In 1995, Schmidt was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame — only Tom Seaver, Ty Cobb, and Hank Aaron had previously received more than Schmidt’s 96.5% vote share. The same year, his friend, Phillies favorite Richie Ashburn, was elected by the Veterans Committee, and Cooperstown was mobbed on July 30, 1995, by 28,000 Phillies fans.94 Earlier that month, Philadelphia magazine had published a controversial piece on Schmidt (as it had done a year earlier just before Steve Carlton’s induction95), quoting him as saying that Philadelphia “never did anything for me and, in general, made life miserable for me.”96 Schmidt had often been criticized throughout his career in the Philadelphia media for being too cool, too aloof, and not appearing to give the game his all. He was occasionally quoted in the press complaining about the fans, the front office, and even the stadium. As a result of his history with the media and the fans in Philadelphia, Schmidt was concerned that his comments, coupled with the love that Phillies fans had for Ashburn, might sour the day for him.97 With that in mind, he worked hard on his speech and made sure to make peace with the fans right at the start of it, stating “If I had to do it all over again, I’d do it in Philadelphia. The only thing I’d change would be me. I would be less sensitive, more outgoing and more appreciative of what you expected from me.”98 Phillies fans appreciated the effort, and he was roundly cheered, starting a thaw that remains in place to the present day.

In 2002, Schmidt was invited by Larry Bowa, then the team’s manager, to join the Phillies as a spring training instructor, a role he continued annually through 2018. In 2004, he accepted the Phillies’ offer to become the manager of the Single-A Clearwater Threshers. Schmidt enjoyed managing the team but was less happy with the long bus rides and the Florida humidity and decided not to return for 2005. In his 2006 book Clearing the Bases (an autobiography of sorts, focusing equally on his opinions on baseball issues of the day), he described his time managing the Threshers, writing of the difficulty he had with telling a player the team had released him, and making an argument for teams bumping up salaries for minor league managers in order to draw major league All-Stars to the job.99

Clearing the Bases was Schmidt’s third book, not surprising given his reputation as a cerebral ballplayer. In 1982, he wrote Always on the Offense, in which he discussed his philosophy on hitting and base running. He also offered further thoughts on the game and picked his “ultimate team of National Leaguers,” including teammates Manny Trillo, Garry Maddox, and Steve Carlton, and, modestly, the Braves’ Bob Horner at third base.100 In 1994, he wrote another hitting instructional book, entitled The Mike Schmidt Study: Hitting Theory, Skills and Technique, as well as a version targeted to young ballplayers. Schmidt continued as a scribe in 2006, writing columns on an occasional basis for the AP covering various baseball topics.

Following his playing career, Schmidt moved to Jupiter, Florida, with his wife, Donna, and two children (Jessica, born in 1978, and Jonathan, born in 1980). As of March 2021, he had two grandchildren as well. He made regular appearances over the years at Phillies games, returning for special events including Phillies alumni weekends each August, and many of the annual Phillies Phestivals that raised funds to fight ALS. Schmidt’s return in 2009 to deliver a touching tribute to his longtime friend Harry Kalas at his public memorial service at Citizens Bank Park, a televised event widely viewed throughout the Philadelphia region, had the unintended effect of helping turn the tide of local public opinion even more in his favor.101 Since 2014, he has served as a color commentator for Sunday home telecasts (advertised as “Sundays with Schmidt”).102 Long active in charitable work, his own organization, Winner’s Circle Charities, has raised more than $2.5 million for charitable causes.103

Looking back in 2020, Schmidt told a reporter, “I’ve been unbelievably blessed. My boyhood dreams came true tenfold. Of course, every player who makes it to the major leagues would have to say the same thing. Dreams are the wonders of life. I used to dream as a kid about Crosley Field in Cincinnati, with the terrace, where my father used to take me once or twice a year. I dreamt of players like Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson and Pete Rose and Johnny Bench. I mean, I ended up on the same team as Pete Rose! I’m sure I told him, you know, kidding around, ‘I used to dream about you, Pete!’ I had his poster on the back of my bedroom door. I ended up being friends with all of those guys! Can you believe that? It’s absolutely ridiculous the way my dreams have come true.”104

Mike Schmidt is undoubtedly the greatest player in the history of the Philadelphia Phillies. He is nearly universally viewed as the greatest third baseman in history as well, and while his hitting was his calling card, those who watched him on a daily basis, as well as those who didn’t but have the benefit of modern fielding statistics, know how excellent he was at the hot corner.105 During his career, he was underappreciated by the fan base, partly because his own high level of skill made it seem that he lacked the blue-collar work ethic that local crowds have always loved. Some ill-timed comments, played up by the press, also made him appear ungrateful, and the local media occasionally sought to tear him down.

But despite all that, his incredible ability, his work ethic, and his leadership during the Phillies’ first “Golden Era” inspired generations of Phillies fans and young ballplayers. One of them is Hall of Famer Mike Piazza, who has proudly shared a photo of himself as a boy with Schmidt106 and described Schmidt as his hero: “I loved Michael Jack. I idolized him. I liked his game, his swagger, and especially his controlled aggression.”107 Schmidt achieved his baseball dreams, and happily for all, he regained the favor of Phillies fans with his 1995 Hall of Fame induction speech. They are proud to consider this legend one of their own.

Last revised: April 8, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello, Gregory H. Wolf, and Norman Macht,and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the authors also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Joseph Jack “Smitty” Schmidt,” Dayton Daily News, October 29, 2011 (https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/dayton/obituary.aspx?n=joseph-jack-schmidt-smitty&pid=154304358&fhid=5161, accessed February 8, 2021).

2 Mickey Zezzo, “Pool Blues,” Dayton Daily News, September 3, 1995, 1B, 2B.

3 Michael Woody, “Memories of Philipps Aquatic Club, Dayton Local, July 7, 2016 (https://www.daytonlocal.com/blog/history/memories-of-phillips-aquatic-club.asp, accessed February 8, 2021).

4 Brian Kollars, “Schmidt Likes What They’ve Done to the Neighborhood,” Dayton Daily News, August 28, 2014, (https://www.daytondailynews.com/sports/schmidt-likes-what-they-done-the-neighborhood/OV1f3b2IHsVOkwN97bCmoL/, accessed February 8, 2021).

5 Si Burick, “How Mike Schmidt Survived Grabbing Live 4,000-Volt Wire,” Dayton Daily News, June 25, 1974, 7.

6 While his father may have been known as “Smitty,” Mike’s most common nickname is “Schmitty,” but in Philadelphia he is equally known as “Michael Jack,” thanks to Phillies broadcaster Harry Kalas regularly calling his home runs with some variation of “That ball is outta here! And Michael Jack Schmidt has given the Phillies the lead!” Schmidt acknowledged Kalas making that name popular in his eulogy for Kalas at Citizens Bank Park in 2009, available at approximately the 46:00 mark on YouTube, at https://youtu.be/HP5RJMZPXX0.

7 Tracy Lockwood, “Mike Schmidt’s Humility Makes a Big Hit,” Philadelphia Daily News, August 2, 1982, 25.

8 Meghan Montemurro, “Mike Schmidt: Only good vibes in Phillies’ clubhouse,” Wilmington News Journal, June 4, 2016 (accessed February 18, 2021 from https://www.delawareonline.com/story/sports/mlb/phillies/2016/06/04/mike-schmidt-only-good-vibes-phillies-clubhouse/85409608/).

9 “Baseball’s Premier Home Run Hitter,” Phillies 1984 Yearbook, Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Phillies, 1984, 62. Demonstrating the team’s focus on Schmidt as a drawing card from early one, he was pictured, usually in a group but occasionally as the primary subject, on the cover of every Phillies yearbook from 1974 through the end of his career, other than 1981 (Pete Rose’s World Series ring) and 1988 (generic stadium photo).

10 Bob Hertzel, “Phillies’ Star Mike Schmidt Was Also-Ran at Dayton,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 8, 1974, 31.

11 Kollars “Schmidt Likes What They’ve Done to the Neighborhood.”

12 Marty Williams, “Kees Scarff Wraps Up Class AA Batting Titles,” Dayton Daily News, September 1, 1968, 6D.

13 Marty Williams, “Fairview’s Schmidt Wren’s Newest Star,” Dayton Daily News, June 8, 1969, 11D.

14 Rob Maadi, Mike Schmidt: The Phillies’ Legendary Slugger, Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010, 3-15.

15 Ritter Collett, “Journal of Sports,” Dayton Journal Herald, August 27, 1970, 26. Collett also notes that Schmidt walked onto the Ohio U. basketball team and actually made the team, but he was not cleared to play by doctors.

16 “Baseball’s Premier Home Run Hitter,” 62-63.

17 Stan Hochman, Mike Schmidt: Baseball’s King of Swing, New York: Random House, 1983, 22-27.

18 Duke DeLuca, “Hot Royals Win on Field, Lose 2 Players to Omaha,” Reading Eagle. June 18, 1971, 26.

19 Hochman, 29-32.

20 Maadi, 17-18.

21 Interview on “MLB Tonight,” MLB Network, May 23, 2020 (available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBRRDGmeKE4).

22 Tom Van Hyning, “Balor Moore remembers his November 25th, 1973 Nine-Inning Perfect Game in Puerto Rico,” Beisbol 101, https://www.beisbol101.com/balor-moore-remembers-his-november-25th-1973-nine-inning-perfect-game-in-puerto-rico/, accessed January 1, 2021.

23 Hochman, 34-36.

24 Associated Press, “Danny Ozark Named New Phils’ Manager,” Reading Eagle. November 1, 1972, 60.

25 Hochman, 37.

26 “Baseball’s Premier Home Run Hitter,” 63.

27 Hochman, 37-43.

28 Maadi, 31-35.

29 Hochman, 46-55.

30 Maadi, 37-38.

31 United Press International, Huntingdon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, June 11, 1974.

32 Ken Rappoport, “Schmidt Hits Roof,” Reading Eagle. June 11, 1974, 22.

33 MLB.com describes WAR, an acronym for Wins Above Replacement as follows: “WAR measures a player’s value in all facets of the game by deciphering how many more wins he’s worth than a replacement-level player at his same position (e.g., a Minor League replacement or a readily available fill-in free agent).” (http://m.mlb.com/glossary/advanced-stats/wins-above-replacement) According to BaseballReference.com, the scale for a single season is as follows: “8+ MVP Quality, 5+ All-Star Quality, 2+ Starter, 0-2 Reserve, <0 Replacement Level.” Between 1974 and 1987, Mike Schmidt’s WAR dipped below 6.2 only once (1984, at 5.7), and hit 8+ four times. Per BaseballReference.com, his career WAR of 106.9 presently ranks 25th of all-time, nine slots above the next third baseman on the list, Eddie Mathews.

34 Hochman, 46-57.

35 Maadi, 42-45.

36 Associated Press. “Schmidt Rips Four,” Reading Eagle. April 18, 1976, 61.

37 Andy Friedman, “Storybook Season: An Interview with Mike Schmidt,” The New Yorker, October 7, 2020 (accessed February 8, 2021, at https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/storybook-season-an-interview-with-mike-schmidt).

38 Hochman, 67-68.

39 Mike Schmidt with Glen Waggoner, Clearing the Bases: Juiced Players, Monster Salaries, Sham Records, and a Hall of Famer’s Search for the Soul of Baseball, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006, 45.

40 Associated Press, “Schmidt Joins Elite,” Reading Eagle. March 5, 1977, 8.

41 Associated Press, “Fight Night: Phils Lose on Pass,” Reading Eagle. July 9, 1977, 6.

42 Hochman, 68-76.

43 Tony Zonca, “Phils Botch Another Opener,” Reading Eagle. April 8, 1978, 6, 9.

44 Zonca, “Phils Botch Another Opener.”

45 Hochman, 77.

46 John W. Smith, “SportopicS: Playoff Quotebook,” Reading Eagle. October 13, 1978, 26.

47 Joseph Durso, “Rose Signed by Phils to $3.2 Million Pact,” New York Times. December 6, 1978, Section A, 1.

48 Bill Conlin, “Batting Cleanup: Bill Conlin,” Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997, 38.

49 Mike Schmidt, “Schmidt: There Will Never Be Another Pete Rose,” Associated Press. April 12, 2013, accessed January 1, 2021 from https://apnews.com/article/441eba3a3ac44bcfaa9a00530582d692.

50 Dave Nightingale, “Flags Blew an Early Omen to Schmidt,” Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1979.

51 Thomas Boswell, “Schmidt in Heaven and Worried,” Washington Post. July 29, 1979, accessed January 21, 2021 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1979/07/29/schmidt-in-heaven-and-worried/eb896b3c-1637-43a2-847f-e5db6aae933b/.

52 Hochman, 80-90.

53 Schmidt’s 1980 was incredible, but his batting average had actually dipped below .300 to stay by June 2. He did hit over .300 in the months of May and August. His on-base percentage, on the other hand, barely dipped below .350 and ended up at .380, a significant reason why his OPS of 1.004 led the National League.

54 Friedman, “Storybook Season: An Interview with Mike Schmidt.”

55 Hochman, 91-98.

56 Friedman, “Storybook Season: An Interview with Mike Schmidt.”

57 Jim Hogan, “Catching Up with No. 20 in 2020,” in 2020 Philadelphia Phillies Yearbook, Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Phillies, 2020, 141.

58 Bob Ibach and Tim Panaccio, The Comeback Kids, United States: Bel Air Printing Co-op., 1980, 11.

59 John W. Smith, “Bitter Memories Washed Away,” Reading Eagle. October 13, 1980, 20.

60 Associated Press, “Schmidt’s Hit Earns Series MVP Award,” Reading Eagle. October 22, 1980, 57.

61 John W. Smith, “Phillies Top Dogs in Baseball,” Reading Eagle. October 22, 1980, 57.

62 Interview on MLB Tonight.

63 Tom Cushman, “The day the Phillies won the 1980 World Series,” Philadelphia Daily News, October 22, 1980, accessed February 8, 2021, from https://www.inquirer.com/philly/sports/phillies/The_day_the_Phillies_won_the_1980_World_Series.html.

64 Lewis Freedman, “Hero Schmidt: Amid Storm, Calm,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 22, 1980, accessed February 8, 2021, from https://1980phillies.jimdofree.com/october/october-22/philadelphia-inquirer/).

65 Matt Breen, “Extra Innings: Forty years ago today, the Phillies finally paraded as world champions,” Philadelphia Inquirer. October 22, 2020, accessed January 1, 2021 from https://www.inquirer.com/newsletters/phillies/phillies-world-series-1980-mike-schmidt-parade-royals-astros-20201022.html.

66 Ibid.

67 United Press International, “Phillies, fans celebrate with ticker tape parade,” Daily Vidette. October 23, 1980, 12.

68 Associated Press, “Schmidt Unanimous Choice as MVP,” Reading Eagle. November 26, 1980, 22.

69 Hogan, 141.

70 William C. Kashatus, Mike Schmidt: Philadelphia’s Hall of Fame Third Baseman. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2000, 72-79.

71 Associated Press, “Schmidt MVP; He Is Third To Win Consecutive N.L. Awards” Reading Eagle. November 18, 1981, 37.

72 Kashatus, 84.

73 Maadi, 133-134.

74 Vince Nauss, editor, Philadelphia Phillies 1984 Media Guide, Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Phillies, 1984, 76.

75 Maadi, 143.

76 Mike Schmidt and Robert Ellis, The Mike Schmidt Study: Hitting Theory, Skills and Technique, Atlanta: McGriff & Bell Inc., 1994, 123.

77 Schmidt and Waggoner, 60.

78 Bill Conlin, “Fanning the Fire: Schmidt Says He Was Quoted Accurately, Questions Timing of Controversial Article,” Philadelphia Daily News. July 1, 1985.

79 Michael Weinreb, “Throwback Thursday: Mike Schmidt Wigs Out in Philadelphia,” June 30, 2016, Vice, accessed February 18, 2021 from https://www.vice.com/en/article/bmqn4q/throwback-thursday-mike-schmidt-wigs-out-in-philadelphia.

80 Mark Whicker, “Schmidt shows his rarest side to fickle fans,” Boca Raton News, July 3, 1985, 3C. It is well worth searching on Google for “Mike Schmidt” and “wig” to see a picture of Schmidt’s preposterous disguise.

81 Maadi, 148-150.

82 “Rawley, Hayes approve of action by Ueberroth,” Reading Eagle, March 2, 1986, C-15.

83 Maadi, 154-155.

84 Witnessed on television that afternoon by the writers of this article, with memories refreshed by Baseball-Reference.com.

85 Jeff McLane, “Call of 500th Home Run Links Kalas and Schmidt,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 18, 2009: D6. A recording of Kalas’s radio call is available at youtube.com/watch?v=pYeOOxlbBbs.

86 Maadi, 168.

87 Maadi, 175.

88 Kashatus, 107.

89 Maadi, 185-186.

90 Peter Pascarelli, “Mike Schmidt retires,” Philadelphia Inquirer. May 30, 1989, accessed January 21, 2021 from https://www.inquirer.com/philly/sports/phillies/archive_schmidt_original_retirement_story.html/.

91 Bill Brown, “Nobody Did It Better: Schmidt Selected TSN Player of the Decade,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1990, 9-11.

92 Kashatus, 113-115.

93 Schmidt and Waggoner, 74-77.

94 Among the 28,000 fans were the two writers of this biography.

95 Pat Jordan, “Thin Mountain Air,” Philadelphia Magazine, April 1994, accessible at https://thestacks.deadspin.com/thin-air-in-the-mountains-with-steve-carlton-armed-co-478492324.

96 Larry Platt, “The Unloved Mike Schmidt,” Philadelphia Magazine, July 1995, 53-56, 81-82.

97 Maadi, 198-201.

98 “At Hall, Schmidt Pleads for Rose,” Washington Post. July 31, 1995.

99 Schmidt and Waggoner, 168-175.

100 Mike Schmidt with Barbara Walder, Always on the Offense, New York: Atheneum, 1982.

101 Weinreb, “Throwback Thursday: Mike Schmidt Wigs Out in Philadelphia.” Schmidt’s touching eulogy, which also demonstrates his Christian faith, can be streamed at beginning at the 43:00 mark on YouTube, at https://youtu.be/HP5RJMZPXX0.

102 Hogan, 144. Schmidt also worked Saturday home telecasts from 2014-2018.

103 Mike Schmidt’s Winner’s Circle Charities, http://winnerscirclecharities.org. Accessed January 21, 2021.

104 Friedman, “Storybook Season: An Interview with Mike Schmidt.”

105 “Like most above-average defenders, Schmidt can be judged favorably based on modern metrics or traditional statistics. He led NL third basemen six times in participating in double plays, seven times in assists, four times in range factor (per game and per nine innings) and seven times in total zone runs.” Chris Haft, “10 definitive Mike Schmidt moments,” accessed on February 8, 2021 from https://www.mlb.com/news/mike-schmidt-s-top-moments-of-career.

106 Accessible at https://twitter.com/super70ssports/status/1285657069635411974.

107 Mike Piazza with Lonnie Wheeler, Long Shot, New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2013, 13.

Full Name

Michael Jack Schmidt

Born

September 27, 1949 at Dayton, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.