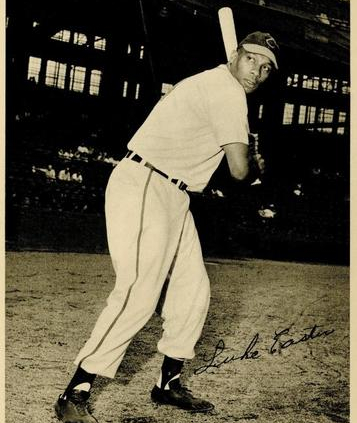

June 23, 1950: Luke Easter slugs longest home run in Cleveland Stadium history

Luke Easter was a phenomenon. His imposing stature (6-feet-4) and friendly disposition may have led some folks to label him as a gentle giant, but there was nothing gentle about the tremendous clouts Easter belted around ballparks coast to coast in a career that began with Black independent clubs in the late 1930s and ended in the International League in the 1960s. While segregation delayed Easter’s arrival in the White major leagues, he went on to play in nearly 500 games with the Cleveland Indians, finish in the American League’s top 10 in home runs three times, and slug the longest-ever home run at Cleveland Stadium.

Luke Easter was a phenomenon. His imposing stature (6-feet-4) and friendly disposition may have led some folks to label him as a gentle giant, but there was nothing gentle about the tremendous clouts Easter belted around ballparks coast to coast in a career that began with Black independent clubs in the late 1930s and ended in the International League in the 1960s. While segregation delayed Easter’s arrival in the White major leagues, he went on to play in nearly 500 games with the Cleveland Indians, finish in the American League’s top 10 in home runs three times, and slug the longest-ever home run at Cleveland Stadium.

In 1946 Easter – who had played for a St. Louis-based Black elite independent team before serving in the Army during World War II – joined the Cincinnati Crescents. The Crescents were not a member of a sanctioned league, and instead, barnstormed against Negro League teams. As part of that tour, the Crescents played at New York’s Polo Grounds, where Easter unloaded a home run to the distant center-field bleachers. “He hit it halfway up the stands, about 500 feet,” said teammate Bob Thurman. “The thing about it – it was a line drive.”1

Easter spent the next two seasons with the Negro National League’s Homestead Grays, and Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck signed him to a contract on February 19, 1949. Cleveland optioned Easter to the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League.

During the first half of the 1949 season, fans flocked to ballparks across the PCL in hopes of seeing Easter hit one of his monster blasts,2 and Easter smacked home runs at an incredible rate. In only 80 games with the Padres, he hit 25 homers, drove in 92 runs, and batted .363.

Easter’s gaudy PCL statistics were even more impressive because he was playing on an injured right knee. He traveled to Cleveland for surgery on his kneecap on July 12.

After a month of rehabilitation, it was believed that Easter could resume playing baseball, but he did not return to San Diego.3 Instead, he remained in Cleveland and made his AL debut as a pinch-hitter on August 11, 1949, a week after his 34th birthday. Easter appeared in 21 games for the 1949 Indians, who followed up their 1948 World Series championship with a third-place finish.

The 1950 season was one of transition for Cleveland,4 and a significant switch was at first base. In December 1948, the Indians had acquired veteran Mickey Vernon, who was equally adept with the baseball bat and a fielding glove, as part of a five-player deal with the Washington Senators. With Vernon seemingly entrenched at first base, Indians player-manager Lou Boudreau stationed Easter in right field at the beginning of the 1950 season.

But the 32-year-old Vernon struggled at the plate. On May 9 at Philadelphia, Boudreau inserted Easter as the starting first baseman. (Bob Kennedy took over in right field.)

Easter and Vernon shared the first-base job until the end of May. Then Easter took over on a full-time basis, and Vernon was dealt back to Washington for relief pitcher Dick Weik on June 14. Easter’s bat heated up the in new role; after a two-homer game against the New York Yankees on June 22, he had 6 home runs and a .314 average in June.

On June 23 the Senators came to Cleveland Stadium to begin a four-game series. Cleveland was on a 14-game homestand and thus far was 8-2 against the AL’s Eastern teams. The Indians (33-25) trailed the first-place Detroit Tigers (37-18) by 5½ games. The fifth-place Senators (27-31) were 11½ games off the pace.

Left-hander Bob Ross started for the Senators. Ross, a 21-year-old rookie from Fullerton, California, was pitching in only his second big-league game and making his first start. Upon observing cavernous Cleveland Stadium, he remarked to Senators coach George Myatt, “Gosh, what a big place this is.”5

The Indians’ Bob Lemon entered with an 8-4 record and a 4.59 ERA. He had a mixed record against the Senators in 1950, shutting out Washington on three hits on May 25 in Cleveland but failing to make it out of the third inning at Griffith Stadium on June 8, giving up six runs (five earned) in a 7-6 loss.

This time, the score was tied 1-1 until the bottom of the third inning, when Ross issued consecutive walks to Lemon and Dale Mitchell, and Kennedy sacrificed the runners up a base. Easter, batting third in the Indians’ lineup, deposited his 10th home run of the season just inside the right-field foul pole and over the Indians’ bullpen, giving Cleveland a 4-1 lead.

Ross continued to have control problems. In the bottom of the fourth, the Indians added two more runs without the benefit of a hit. Ross walked Bobby Avila and Jim Hegan to start the frame. Lemon sacrificed the runners to second and third.

Mitchell tapped a groundball to Nats second baseman Sam Dente, whose throw home was late and Avila scored the Indians’ fifth run. Washington manager Bucky Harris gave the hook to the rookie pitcher and replaced him with veteran reliever Joe Haynes. Haynes walked Kennedy to reload the bases. Easter followed with a lineout to left field. Hegan came home on the sacrifice fly, and Cleveland now led 6-1.

Lemon continued to shut down the Senators, and Cleveland’s lead was still five runs when the Indians batted in the sixth. With one down, Mitchell singled to right field and advanced to second on a groundout, bringing up Easter.

Easter clobbered a 3-and-0 pitch from Haynes. The baseball traveled over the auxiliary scoreboard that hung over the upper right-field seats in Section 4. It landed in the box seats past the scoreboard, 477 feet from home plate. It was Easter’s 11th home run of 1950 and fourth in the last two games, and it gave him a six-RBI game.

The Indians scored another run in the sixth and four more in the seventh, highlighted by Al Rosen’s bases-loaded triple. They now had a commanding 13-1 lead.

Washington reached Lemon for three runs in the eighth inning, with one scoring on Vernon’s sacrifice fly, making the final score 13-4. Lemon improved to 9-4, giving him the AL lead in wins. He allowed seven walks and five hits, while striking out four.

“It’s a pleasure to see the guys wearing the same color uniforms score all those runs,” Lemon said. “Bless ’em all.”6

Easter’s mammoth home run was the biggest topic of discussion afterward. He was asked if it was the longest home run he had ever hit. “No, that wasn’t the longest homer I ever hit,” said Easter, mentioning his 1946 homer in New York. “Hit one into the center field stands at the Polo Grounds out where the dressing rooms are.”7

To support his claim, Easter told reporters to ask José Santiago about the Polo Grounds homer. Santiago, who was an Indians’ minor-league pitcher in 1950, was on the hill that day for the opposition.8

When a reporter remarked to Easter that he really poled the long home run, Easter responded, “When I try to pole them on purpose they don’t go nowhere. I hit the ball where it’s pitched at.”9

Easter’s home run against the Senators topped the list of at least one longtime observer. Ed Bang, Cleveland News sports editor since 1907, wrote of Easter’s tremendous clout, “I have seen them all from the late Babe Ruth on down to hit home runs, but none ever connected for a drive to match that of Luke.”10

Easter spent the rest of the 1950 season at first for the Indians, batting .280 with 28 homers and 107 RBIs, as Cleveland (92-62) finished fourth in the AL, six games behind first-place New York. Two seasons later, in 1952, he was named Sporting News AL Player of the Year.

Easter played with Cleveland from 1950 to 1954, hitting 93 home runs, driving in 340 runs, batting .274, and recording what went down as the longest home run in the Indians’ 62-year stay at Cleveland Stadium.

“Had Luke come up to the big leagues as a young man, there’s no telling what numbers he would have had,” said Al Rosen.11

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Larry DeFillippo and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information, including the box score and play-by-play.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CLE/CLE195006230.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1950/B06240CLE1950.htm

Notes

1 Justin Murphy, SABR BioProject, Luke Easter, accessed April 20, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/luke-easter/.

2 When the Padres made their first visit to Hollywood for a series against the Hollywood Stars, all the box and reserved seats were sold out weeks in advance, and hundreds of seats were added to Hollywood’s Gilmore Field. On May 22, 1949, an overflow crowd of 23,366 came out to see a game between San Diego and the San Francisco Seals, setting a new Sunday attendance record at San Francisco’s Seals Stadium. “Luke Easter Helps Draw Record Sunday Crowd at San Francisco, The Sporting News, June 1, 1949: 16.

3 John B. Old, “Fans Believe Luke Went East to Stay,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1949: 25.

4 Al Rosen took over at third base for Ken Keltner. Ray Boone supplanted player-manager Lou Boudreau as starting shortstop. Joe Gordon, who was playing in his final major-league season, turned the second-base job over to Bobby Avila.

5 Hal Lebovitz, “Lemon Is First to Notch 9th,” Cleveland News, June 24, 1950: 22.

6 “Lemon Is First to Notch 9th.”

7 Hal Lebovitz, “We Were ‘Lukers,’ Not ‘Booers,’ Say Fans,” Cleveland News, June 24, 1950: 22

8 “We Were ‘Lukers,’ Not ‘Booers,’ Say Fans.”

9 “We Were ‘Lukers,’ Not ‘Booers,’ Say Fans.”

10 Ed Bang, “Bang Calls It Longest Homer,” Cleveland News, June 24, 1950: 23.

11 Murphy, “Luke Easter,” SABR BioProject.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Indians 13

Washington Senators 4

Cleveland Stadium

Cleveland, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.