May 27, 1888: Bridegroom Adonis Terry no-hits Louisville on a Sunday in Queens

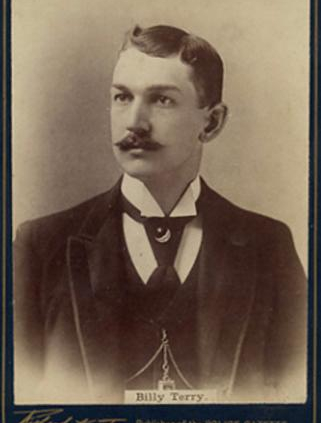

Early in the fall of 1887, Brooklyn Grays pitcher Will Terry married, breaking the heart of many a female admirer.1 Recently dubbed “Adonis” by the New York Tribune,2 the tall, slender 23-year-old was popular among men and women alike for his handsome looks, temperate manner and “gentlemanly … conduct on and off the field.”3

Early in the fall of 1887, Brooklyn Grays pitcher Will Terry married, breaking the heart of many a female admirer.1 Recently dubbed “Adonis” by the New York Tribune,2 the tall, slender 23-year-old was popular among men and women alike for his handsome looks, temperate manner and “gentlemanly … conduct on and off the field.”3

On the diamond, Terry was a “splendid pitcher,” a fine outfielder (according to the legendary Henry Chadwick),4 and possessor of “batting qualities that rank A1.”5 Mainstay of the Brooklyn rotation since he won 16 games in 1883 when they were the Interstate League Greys, he was the team’s longest tenured and most popular member.6 “Pity there are not more Terrys in the profession,” one anonymous Sporting Life writer lamented.7

As the Terrys began their new life together, Brooklyn owner Charles Byrne consummated another union. He purchased Erastus Wiman’s Metropolitans franchise and combined their top players, including slugging first baseman Dave Orr, outfielder Darby O’Brien, infielder Paul Radford, and pitcher Al Mays, with the best of his Grays. In November Byrne purchased a trio of standouts from the reigning American Association champion St. Louis Browns: 20-game-winning pitchers Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz,8 plus catcher Doc Bushong.9

Twice before, Byrne had merged groups of players from defunct competitors into his Brooklyn nine, with mixed results. His first Brooklyn squad captured the 1883 Interstate League pennant with the help of five players added from the league-leading Camden Merritts after they folded in midseason.10 The 1885 Grays never jelled11 and stumbled to a fifth-place finish after incorporating six members of the disbanded National League Cleveland Blues.12 “True, there will be some lack of harmony,” said a Sporting Life prognosticator about the 1888 season, “but still I think that team from the City of Churches will be so strong … that it will win the championship anyhow.”13

While club secretary Charles Ebbets directed the clearing of snow from Washington Park in preparation for preseason games,14 Sporting Life identified fans for whom the team was “a special interest.” “Look at the list of brides to witness the games – Mrs. Terry, Mrs. [Ed] Silch, Mrs. Caruthers and Mrs. George [“Germany”] Smith.”15 Joking that the foursome “threaten to create an epidemic in the Brooklyn team,” columnist Ollie Caylor identified O’Brien, Orr, and Mays as next to catch the marrying bug.16

In describing the team’s April 7 victory over a Yale college nine, the New York Evening World noted that “honeymooning does not seem to interfere with the ball-playing abilities of the bridegrooms.”17 A few days later, the Brooklyn Union and the Brooklyn Citizen began calling them the Bridegrooms with a capital “B.”18 Newspapers in metropolitan New York and across the country began calling them the same: some immediately, others months later.19

In addition to new teammates, new spouses, and a new team name, the Bridegrooms also had a new manager. Byrne, unable to win an American Association crown in his 2½ seasons as owner-manager, handed the managing reins to Bill McGunnigle, a weak-hitting outfielder and occasional pitcher during his playing days. McGunnigle’s success leading the Lowell Browns to the 1887 New England League pennant had earned him Byrne’s admiration, and the job.

Blessed with a stable of accomplished pitchers, McGunnigle began the season with a four-man pitching rotation. Caruthers, Terry, Mays, and rookie Mickey Hughes started and won Brooklyn’s first four games. The Bridegrooms were 19-9 and in third place when the Louisville Colonels came to Brooklyn for a four-game series starting May 25.

The Colonels season had been a rocky one. Their offensive star, Pete Browning (a two-time batting champ who’d hit .402 and had 118 RBIs in 1887), refused to come to terms until the end of March. Pitcher Ice Box Chamberlain, a rookie sensation in 1887, held out even longer. They lost their first five games, allowing double-digit runs in four straight. In the middle of a 19-game road trip, they’d lost six of their last seven and carried a 9-18 record heading into Brooklyn.

Former Colonel Al Mays won the series opener for Brooklyn over the “Red Devils,” in an unremarkable game played in a misty rain.20 The Louisville Courier-Journal said the Colonels deserved the 4-1 loss in a story pejoratively headlined “Cigar-Sign Colonels.”21 Rain washed out the second game of the series, giving both sides Saturday off.

In the pitcher’s box on Sunday for Brooklyn was Adonis Terry. He boasted a 5-2 record, with a 1.83 ERA (12 earned runs in 59 innings).22 He’d also struck out seven or more batters in his last four starts, the longest such run of his career so far. Terry had allowed just one unearned run in his last start, a complete-game loss to former teammate Henry Porter and the Kansas City Cowboys.23 Off to the best start of his career, Terry was ready to make history.

Opposing Terry was Toad Ramsey,24 who’d lost the series opener two days earlier. Born the day after Terry was, Ramsey had been a workhorse for Louisville the previous two seasons. He won 38 games in 1886 and 37 in 1887,25 relying on his “patented drop ball”: a knuckler.26 Poor outings, money problems, and boorish behavior off the field had earned Ramsey a brief suspension earlier in May.27 He’d made amends with manager Kick Kelly but his record was an ugly 2-7 heading into his matchup with Terry.

The rain had cleared and the temperature was in the low 70s as the game got underway at Ridgewood Park. The Bridegrooms played their Sunday home games at the Queens County ballyard, where Blue Law enforcement was less stringent than in neighboring Brooklyn.28 This, their sixth Ridgewood Sunday match of the season, drew 4,800 fans.29

For just the second time that season, Brooklyn elected to have the visitors bat first.30 Terry walked Louisville leadoff batter, Hub Collins, who advanced to second on a passed ball and to third on the first out. Browning hit a “rifle shot” that left fielder O’Brien grabbed in “brilliant style,” keeping Collins at third.31 Terry retired Reddy Mack next, stranding Collins. In the bottom of the first, Orr stroked a two-out double for Brooklyn, but died there as Ramsey fanned Foutz.

Ramsey and Terry matched goose eggs through the first five innings. Ramsey worked around a two-out single by Bill McClellan in the third and Germany Smith’s single and stolen base in the fourth. Terry had smoother sailing, retiring 15 straight from the second inning though the sixth, striking out the side in the third, and fanning two of three in the fourth and sixth.

In the bottom of the sixth, Brooklyn “found Ramsey’s curves.”32 After Mack misplayed a “hot grounder” from Foutz, Germany Smith sent one flying past the reach of second baseman Collins for a triple, plating Foutz. Ramsey retired the next two batters, the last on catcher John Kerins’ “sharp fly tip catch”: a foul tip, which in 1888 retired the batter, regardless of the count.

In the seventh, Terry’s one-out error put Kerins on first. After catcher Jimmy Peoples’ low throw advanced Kerins to second base, Terry fanned Browning and made an unassisted out at first base to keep the Colonels hitless and scoreless. Terry’s walk to rookie Skyrocket Smith in the eighth proved harmless after Peoples’ foul tip grab and a “finely judged catch” by O’Brien.

The Bridegrooms extended their one-run lead in the eighth inning. McClellan led off with a double down the left-field line and scored on an opposite-field double from Orr. After Foutz flied out,33 Germany Smith drove in Orr on a triple to left field that Collins couldn’t flag down, despite playing deep. O’Brien’s “lucky bounder” eluded speedy right fielder Chicken Wolf, allowing Germany to score Brooklyn’s fourth run.

The crowd sat tight, hoping Terry could deliver the shutout in the ninth. The first batter, Collins, hit a grounder that McClellan muffed, then threw wildly to first. Orr corralled the errant throw, keeping Collins at first. When the next batter, Kerins, was retired on another foul tip catch, Collins broke for second, where he was gunned down by Peoples for a double play.

Louisville’s last hope was Browning. The Louisville Slugger proved “an easy victim.”34 Browning hit a comebacker to Terry, who threw to Orr for the final out.

The Bridegrooms had a 4-0 win, Terry had his second no-hitter,35 and Ridgewood Park had its first and only major-league no-hitter.36 The Brooklyn Eagle marveled at Terry’s “splendid strategic work” and how his “well disguised change of pace bothered the Louisville batsmen greatly.”37 They counted nearly 30 called strikes and eight strikeouts, most of them swinging.

Brooklyn swept the rest of its series with Louisville, then hosted a four-game set with the first-place Cincinnati Red Stockings. In the opener of that series, Terry earned a complete-game walk-off victory when his single in the bottom of the 13th inning brought home the winning run.38 The win vaulted Brooklyn into first place, where it stayed for 51 of the next 52 days before yielding to the eventual Association champions, the St. Louis Browns.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Mike Huber and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, MyHeritage.com, and FamilySearch.com for pertinent material. He also consulted SABR Baseball Biography Project biographies of several players who participated in the game and other related figures, including Ronald G. Shafer’s biography of Charles Byrne, Chris Rainey’s biography of Toad Ramsey, Bob Bailey’s biography of William “Chicken” Wolf, Philip Von Borries’ biography of Pete Browning, and Bill Lamb’s article on Ridgewood Park. Other sources included David Nemec’s The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994) and game summaries published in the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Sun, New York Times and Louisville Courier-Journal.

Notes

1 New York City marriage records show that Adonis married Cecilia E. Moore on September 27. Sporting Life stated that Terry was married “since the close of [the 1887] season,” which ended for Brooklyn on October 10. Either way, there was some urgency to their nuptials, as Mrs. Terry was pregnant with their first child, a daughter she delivered in January. Cecilia was identified as a Brooklyn girl in an Adonis obituary. “New York, New York City Marriage Records, 1829-1940,” database, FamilySearch, William Terry and Cecilia Moore, 27 Sep 1887; citing Marriage, Manhattan, New York, New York, United States, New York City Municipal Archives, New York; FHL microfilm 1,556,693, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24MV-JRD, accessed April 20, 2022; “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, April 11, 1888: 6; “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 23, 1888: 4; “Death of Bill Terry Recalls Brooklyn Triumphs,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 1, 1915: 8.

2 Tongue-in-cheek, the New York Tribune asserted that Terry earned the nickname because he looked nothing like actor Henry Dixey, the lead actor in the long-running burlesque play Adonis, which showcased Dixey’s striking physique. “Two Players in Collision,” New York Tribune, September 11, 1887: 16. Kurt Gänzl, “Boylesque in Operetta, or: Meet Mr. Henry E. Dixey,” August 14, 2014, Operetta Research Center website, http://operetta-research-center.org/boylesque-meet-mr-henry-e-dixey/, accessed April 20, 2022; Trav S.D., “Henry E. Dixey: Adonis,” Travalanche website, https://travsd.wordpress.com/2013/01/06/stars-of-vaudeville-559-henry-e-dixey/, accessed April 20, 2022.

3 “Base Ball Personals,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 6, 1885: 10.

4 Chadwick, often called the “Father of Baseball” and arguably the most influential figure in nineteenth-century baseball, was the editor of Sporting Life in the 1880s. Henry Chadwick, “Chadwick’s Chat,” Sporting Life, October 3, 1888: 6; Andrew Schiff, Henry Chadwick biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/henry-chadwick/.

5 “Jim Mutrie Laughs,” The Sporting News, December 11, 1886: 1.

6 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, December 14, 1887: 6; “Brooklyn’s New Team,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 28, 1886: 16.

7 “Notes and Comments.”

8 Foutz was also an excellent hitter (lifetime .276 batting average), who often played first base or in the outfield when not pitching.

9 The sale of these, and several other Browns players in the offseason, netted Browns owner Chris von der Ahe over $17,000. The fire sale, thought at first to be a payroll-reduction exercise, was revealed by Sporting Life to have been at the request of Browns player-manager Charles Comiskey, who wanted no part of players who disobeyed him. Sporting Life postulated that several of the traded stars had created a mutinous climate for Comiskey. David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 146.

10 Byrne’s acquisitions were position players Bill Greenwood, Frank Fennelly, Jack Corcoran, and Charlie Householder plus pitcher Sam Kimber, who in 1884 tossed the first no-hitter for the Brooklyn franchise. “The Merritt Club Disbands,” Camden (New Jersey) Courier-Post, July 21, 1883: 1; “The Brooklyn Dodgers Long Lost Step-Brother: The 1883 Camden Merritts, July 19, 2020, The Brooklyn Trolley Blogger website, https://thebrooklyntrolleyblogger.blogspot.com/2020/07/the-brooklyn-dodgers-long-lost-step.html, accessed April 20, 2022.

11 In late June Sporting Life reported “no end of trouble in the Brooklyn menagerie,” including Terry complaining of not getting support from the Cleveland clique. After Byrne spoke with nearly all the team’s players, he released manager Charlie Hackett and took the reins himself. From a 15-22 record at the time of Hackett’s release, the Grays improved to 38-37 under Byrne. “The Cleveland Clique,” Sporting Life, June 24, 1885: 5.

12 After the seventh-place Blues folded in January 1885, Byrne hid several of their best players in a hotel during a 10-day waiting period so that he could sign them to play in Brooklyn. That effort netted Byrne six players: Doc Bushong, Pete Hotaling, Bill Phillips, George Pinkney, Germany Smith, and John Harkins. Bushong was immediately transferred by Byrne to the American Association St. Louis Browns, possibly to repay Browns owner Chris von der Ahe for his support of Byrne’s controversial Cleveland signings. Byrne regretted letting Bushong go soon after, as he had played such a prominent role in the Browns’ three consecutive AA championships in 1885 through 1887. “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 6, 1885: 2; Brian McKenna, Doc Bushong SABR bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/doc-bushong/.

13 “The Pennant Race,” Sporting Life, January 4, 1888: 4.

14 “Ready to Play,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 23, 1888: 4.

15 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, March 21, 1888: 5.

16 Ollie Caylor, “Caylor’s Comment,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1888: 3.

17 The Yale squad was led by its pitcher and future football coaching legend Amos Alonzo Stagg. “Bridegroom Ball,” New York Evening World, April 7, 1888: 1.

18 “The Brooklyns Batted,” Brooklyn Union, April 10, 1888: 2; “Another Win for Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 10, 1888: 3.

19 For example, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch began using the name to describe Brooklyn’s team on April 12, the Cincinnati Enquirer on April 28, and New York Times on May 31.

20 “On a Wet Field,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 26, 1888: 1.

21 Louisville pitcher Toad Ramsey was “the only man deserving of favorable mention” for his play in the series opener, according to the same story. “Cigar-Sign Colonels,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 26, 1888: 5.

22 Based on a pitching log for Terry, compiled by the author from Brooklyn and New York City newspaper game summaries and box scores.

23 Terry himself had two of the Bridegrooms’ four hits off Porter. “Brooklyn, 0; Kansas City, 1,” New York Sun, May 20, 1888: 5.

24 Terry and Ramsey had faced off twice before as starting pitchers, splitting two games in 1886. Terry had relieved in three games where Ramsey started for Louisville, all in 1887, including a 27-9 Brooklyn loss a year and a day before this game. “Brooklyn Badly Beaten,” New York Times, May 27, 1887: 2.

25 Ramsey was also the reigning AA strikeout leader, and led the Association in FIP (fielding independent pitching) for both 1886 and 1887.

26 Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds., Nineteenth Century Stars (Kansas City, Missouri: SABR, 1989), 105.

27 According to the Louisville Courier-Journal, Ramsey was suspended for unsatisfactory work, quarreling with Kelly, drawing large pay advances to cover debts and arriving late to practice. While he was suspended, the Athletics of Philadelphia made an offer for Ramsey that was declined. Realizing he couldn’t do without Ramsey in the box, Kelly reinstated him five days later. “Ramsey Indefinitely Suspended,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 8, 1888: 2; “The First Eastern Trip,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 12, 1888: 3; “Ramsey to Join the Club,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 13, 1888: 14; “Ramsey Not for Sale,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 16, 1888: 3.

28 Playing Sunday home games at Ridgewood was a practice Brooklyn had adopted in May 1886. The park was in Queens County, then considered one of three counties comprising Long Island, along with Nassau and Suffolk counties. Queens County was incorporated into New York City in 1898 as one of its five boroughs, along with Kings County (Brooklyn), Richmond County (Staten Island), Manhattan County and Bronx County.

29 Given Terry’s popularity with female fans, the Bridegrooms frequently had him in the pitching box for weekend home games, when families, couples, and single women most frequently attended games. This was Terry’s fifth consecutive Saturday or Sunday start at home. “Sunday Ball Playing,” New York Times, May 28, 1888: 5.

30 Brooklyn had elected to bat last the previous Sunday, but for all other home games held to that point they’d batted first.

31 “Not a Base Hit,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 28, 1888: 1.

32 “A Big Day for Terry,” New York Sun, May 28, 1888: 3.

33 With the out, Foutz’s modest seven-game hitting streak ended. He had smacked 13 hits over that span.

34 “Not a Base Hit.”

35 Terry also became the fourth major-league pitcher with multiple no-hitters, joining Larry Corcoran, Pud Galvin, and Al Atkinson. Terry’s first no-hitter, on July 24, 1886, came against the St. Louis Browns. Jimmy Peoples, Brooklyn’s primary catcher in 1886 and one of four in manager McGunnigle’s 1888 catching merry-go-round (the Bridegrooms used a different catcher in each of their first four regular-season games in 1888), caught both of Terry’s no-hitters. The Brooklyn Eagle, which invariably referred to Jimmy as Peebles, called Terry’s 1888 no-hitter “the game of [Peoples’] life.” “Not a Base Hit.”

36 The next major-league no-hitter tossed in a Queens ballpark was Jim Bunning’s Father’s Day perfect game at Shea Stadium on June 21, 1964. It was the first National League perfect game since the 1880s.

37 The Brooklyn Eagle also credited the Louisville battery for a game well played, calling the contest “a masterly exhibition of battery work on both sides.” “Not a Base Hit.”

38 “Two Games for Brooklyn,” New York Times, May 31, 1888: 3.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Bridegrooms 4

Louisville Colonels 0

Ridgewood Park

New York, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.