Babe Ruth And Lou Gehrig

This article was written by Tara Krieger

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig weren’t exactly best friends or worst enemies, weren’t exactly master and pupil, weren’t exactly equals on or off the field. Half a generation apart in age1 and polar opposites in temperament, they shared a relationship that ranged between avuncular and distant, and the media generally filled in the rest.

Likely even the casual fan reading this article for the first time is aware that the two most feared bats of the Yankees’ first great dynasty were a study in contrasts – one craving the spotlight, one hiding from it; one hedonistic, one almost puritanical. As much as Ruth’s exploits were exaggerated, Gehrig’s were understated. Ruth stayed out on all-night benders, losing track of how many hot dogs and women he’d had. Gehrig made sure to get 10 hours of sleep a night, was said not to touch alcohol or cigarettes (he did in moderation), and couldn’t string two sentences together in front of a woman who wasn’t his mother or, later, his wife.

Ruth, the established star, led the way during that era that rose during the Roaring Twenties and set during the Depression, and Gehrig, at least in the early going, was content to ride his coattails.

“It’s a pretty big shadow,” Gehrig said. “It gives me lots of room to spread myself.”2

When Gehrig joined the Yankees, the lively ball era – in which soiled baseballs were immediately removed from the game, leading to a spike in offensive production – had been in full swing for a few years. But other than the Babe himself, no American Leaguer had ever hit as many as 40 home runs until 1927.3 And then Gehrig hit 47 that year to Ruth’s immortal 60, and it became clear that celebrity had company.

Over 1,200 home runs socked between them; when Gehrig retired, his 493 dingers were second all-time to Ruth’s 714. Over 4,000 runs scored (Ruth, 2,174; Gehrig, 1,888) and 4,200 runs batted in (Ruth 2,214; Gehrig 1,995).4 Not to mention that they still occupy two of the top three spots in slugging percentage – Ruth, .690 (first); Gehrig, .632 (third)5 – and are both among the top five in on-base percentage.6 In that unforgettable 1927 season, they were singlehandedly outhomering whole teams.7 Hard to believe that in the decade they regularly started alongside each other, 1925 to 1934, the Yankees won “only” four pennants and three World Series.

Number three and number four in the batting order – and eventually on the backs of their jerseys – the Home Run Twins; the Caliph of Clout and the Crown Prince; the Sultan of Swat and the Fence Buster; the Bambino and the Slambino. Ruth was a man of a million monikers, but generally the superlatives the sportswriters tried to bestow on Gehrig in the early days didn’t stick around very long.8 At least until writers noticed that Gehrig hadn’t taken a day off in years and dubbed him the Iron Horse for his durability. But Gehrig coming into his own as a more unassuming superhero was right around the time that the Behemoth went bust. Shifting power dynamics or personalities opened a rift between the one-time odd couple, one that time and tragedy narrowed, but perhaps never quite closed.

Both the only surviving sons9 of working-class German stock: Gehrig, from New York City, the son of immigrants; Ruth, from Baltimore, from an insular ethnic community where communicating via the Muttersprache was common around the house. That’s about all they had in common.

Young Henry Louis and his domineering mother were a tight-knit duo – a counterbalance to his father, a habitually out-of-work lush. The Gehrigs stressed education and fitness as a means to a better life for their son; Lou lived with his parents until age 30. The Ruths were more dysfunctional, sending young George Herman away to a charity reform school at age 7, and divorcing a few years later. They had both died by the time the Babe was 23, and the writers often styled him an “orphan” (even if he himself did not).

On the pair’s barnstorming trip in the fall of 1927, Ruth expressed envy of the parental relationship Gehrig had that he never enjoyed.

“You know, every town we go into, immediately on arrival he writes to his mother and what a wonderful thing it is to have a mother at his age,” a misty-eyed Ruth told a reporter then, recalling that he lost his own mother as a “mere tot.”10

To the extent that Ruth had any parental figures, he found them in the brothers at the St. Mary’s Industrial School, in particular Brother Matthias, whom he credited with teaching him how to play ball. Pitching for St. Mary’s, he caught the eye of Jack Dunn, the manager of the Baltimore Orioles of the International League, who signed him to his first professional contract in 1914, which ultimately led him to the Boston Red Sox rotation the following season. But his success as a pitcher was ancient history by the time Gehrig’s name first appeared in the sports pages.

June 26, 1920 – Ruth, converted into a power-hitting outfielder, had been sold to the New York Yankees that offseason. Just two months into his Yankees career, he had already hit 22 home runs, on the way to nearly doubling the season record he’d set the previous season – from 29 to 54. He didn’t go long that day,11 but a 17-year-old kid dubbed the “Babe Ruth of the High Schools” did.

The baseball team of the now-defunct High School of Commerce in Manhattan had been chosen to travel to Chicago for a promotional intercity championship game against host Lane Technical High School. Gehrig’s ninth-inning grand slam at the park now known as Wrigley Field ensured Commerce – and New York City – the 12-6 victory, and the scholastic title.

Newspapers in both cities bubbled with delight that the sandlot slugger had lived up to the hype12 (albeit repeatedly mangling their subject’s name13). “The real Babe never poled one more thrilling,” wrote James Crusinberry of the Chicago Tribune, who repeatedly referred to him as “‘Babe’ Gherig.”14

Gehrig’s athletic prowess won him a scholarship to Columbia University, where he both played first base and pitched.15 His nine home runs in his lone season with the college club are still the stuff of legend – one off Columbia’s famed sundial, another hitting the steps of the journalism building, both some 400-plus feet from home plate – and Yankees scout Paul Krichell, upon discovering this prodigious hitter while the team was visiting Rutgers, wired general manager Ed Barrow immediately that he’d “just seen another Babe Ruth.”16

The year Gehrig broke in with the Yankees, 1923, Ruth won the AL Most Valuable Player and the Yankees inaugurated their eponymous Stadium. The Babe had hit a home run on Opening Day then, the first in the expansive new ballpark, built to accommodate the throngs rushing to see The Bambino. Over 74,000 strong had shown up to see The Babe’s three-run blast, christening the area beyond the short right-field porch “Ruthville,” and the park “The House That Ruth Built.”

The day of that historic home run, some three miles southwest, Gehrig pulled off his own historic feat for Columbia – from the mound. The Lions southpaw had struck out 17 batters against Williams College – still a campus record that as of 2019 has been equaled but not surpassed – and somehow lost the game. A few weeks later, he’d forsake his quest for cap and gown for a cap and uniform.

So it was that the Titan of Terror should meet his sidekick for the first time in the Yankees clubhouse in June 1923. As teammate Waite Hoyt remembered, Yankees trainer Doc Woods had tapped Ruth on the shoulder as he was tying his shoes and introduced the rookie as “Lou Gehrig from Columbia.”

“Hiya, keed,” said The Babe, addressing Gehrig as he did most acquaintances, names not being his strength.17

A short while later, manager Miller Huggins led Gehrig out onto the ballfield and requested that he take batting practice. Gehrig, nervous, grabbed a bat, which happened to be Ruth’s 48-ounce model. (Gehrig’s bats throughout his career ranged between 35 and 40 ounces.)

Said Hoyt, “Ordinarily, a batter prizes his bat more than he does his watch. In this instance, Ruth could have said, ‘Oh, no, kid, that’s my good one, grab yourself another stick.’ But somehow the Babe didn’t protest; it choked in his throat. He said nothing.”18

After a few misses and false starts, Gehrig found his swing, belting several into Ruthville.

Although Gehrig spent most of the 1923 season at Hartford (and 1924 after that), fans caught their first glimpse of what was to come on September 27, when Gehrig started and batted cleanup behind Ruth for the first time, in Boston.19 In the first inning, Ruth tripled, and Gehrig drove him in with his first major-league home run, over the right-field fence at Fenway Park. The next day, the duo went a combined 9-for-13 with seven runs and seven RBIs (Ruth, 5-for-6, with two doubles and a home run; Gehrig, 4-for-7 with three doubles), in a 24-4 rout. Ruth and Gehrig would also occupy the middle of the lineup in the Saturday doubleheader that closed out the Red Sox series.

The Yankees had already locked up the pennant at that point, and that fall, Gehrig – ineligible for the postseason because he was called up after September 1 – watched from the bench as Ruth batted .368 (7-for-19) with three home runs en route to the Yankees’ first World Series title.

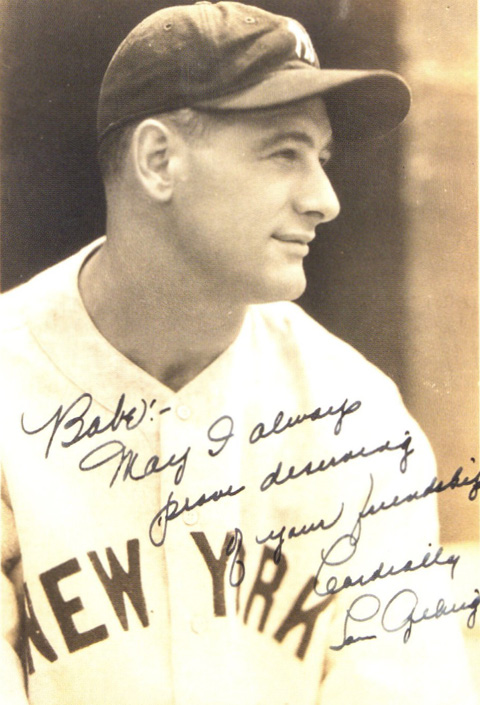

(Photograph signed to Babe Ruth by Lou Gehrig. Courtesy of Hunt Auctions.)

When Gehrig and Ruth next shared the starting nine, on the fateful June 2, 1925, the Yankees were a mess. Floundering in seventh place (of eight), the team was ravaged by age and injury –most notably Ruth, whose personal life finally seemed to be catching up with him. Increasingly at odds with his wife, Helen, and in love with his mistress, Claire – whom he would marry four years later – The Babe had shown up to spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida, out of shape and out of control. His weight had ballooned to at least 256 pounds on his 6-foot-2 frame, and he had little regard to bringing it down, gorging on food and parties and sex and alcohol (yet somehow he managed to bat .447 during the preseason). A bout with the flu didn’t help. On April 7, as the Yankees train made its way north, Ruth collapsed on the platform in Asheville, North Carolina, from what became known as “the bellyache heard ’round the world.”20 The official diagnosis was an intestinal attack requiring abdominal surgery, but rumors spread that he had gotten sick from downing too many hot dogs; that he had contracted venereal disease; or, worst of all, as a media outlet in London put it, that he was dead.21

Not quite that extreme, but it did keep Ruth out of uniform until June 1. Gehrig, intermittently starting and pinch-hitting in 12 of the Yankees’ first 42 games, was batting .167. The day of Ruth’s return, he pinch-hit in the ninth and flied out to left in a loss to Washington. The next day, June 2, Huggins decided to shake up the lineup and gave Gehrig the start over regular Wally Pipp, at first base and in the sixth spot in the order.22 He went 3-for-5 to raise his average almost 75 points. With Ruth batting fourth and going 2-for-4, the Yankees beat the Senators, 8-5. The next time a Yankees box score would appear without the name “Gehrig” was May 2, 1939– so went the unheralded beginning of the Streak of 2,130 games.

As Gehrig hung on Huggins’s every word for help en route to a respectable rookie season – .295 (second-highest among teammates), 20 home runs (third), 68 RBIs (second) – Ruth continued to spiral, showing little effort to get in playing shape. On August 29 Huggins finally had it with his troublesome prima donna and suspended him. In the ensuing shower of obscenities between manager and player,23 Huggins insisted Ruth would not be allowed in uniform again until he at least apologized. A week later, a contrite Ruth swallowed his pride, and Huggins relented. Seemingly reinvigorated, Ruth amassed almost half his offensive statistics for the year in the month of September,24 but it was too little, too late – for Ruth (.290 average, 25 home runs, 67 RBIs) and for the 69-85 Yankees.

The addition of Gehrig to the batting order added a measure of protection for Ruth in the lineup; pitching around his lefty bat meant facing an equally fearsome left-hander with a runner on base. Gehrig and Ruth would appear in 1,344 regular-season starting lineups together as teammates, in 927 of which Ruth hit third and Gehrig fourth (and another 194 when Gehrig hit third and Ruth fourth). Although intentional walks were not regularly totaled during Ruth’s era, Ruth held the career record with 2,062 walks for 66 years – and although he still led the league for seven of the 10 seasons he and Gehrig were regular teammates, he walked somewhat less with Gehrig behind him.25

However, they weren’t quite there yet in 1926. Ruth put forth another banner year – leading the league in on-base percentage, slugging percentage, runs, RBIs, total bases, and of course home runs (and walks), and the Yankees to another pennant. Gehrig, albeit still developing, led the AL in triples and extra-base hits and spent much of the season batting in front of Ruth. However, in the World Series, which the Yankees lost to the Cardinals, he batted fifth to Ruth’s third, with Bob Meusel in between them.26 Gehrig drove in both runs in the Yankees’ Game One victory, including Ruth for the go-ahead in the sixth, and batted .348 for the seven-game set.

But in the span of notable Yankees moments in that fall classic, probably two of the top three belong to The Babe (the third being Cardinals pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander striking out Tony Lazzeri in Game Seven). Ruth became the first person to hit three home runs in a World Series game, when he kept a promise he’d hit one for injured little Johnny Sylvester. (Less known is that Gehrig sent the boy the ball that made the last out of the Series.)27 Ruth also caused the last out – and the Yankees’ loss – when he was caught stealing in the bottom of the ninth of Game Seven. Gehrig was kneeling in the on-deck circle. Neither Ruth nor Gehrig would ever lose another World Series game as teammates – as the Yankees swept their way to titles in 1927, 1928, and 1932.

The year 1927, in which the team epitomized its “Murderers’ Row” nickname28 and won 110 games, saw a concerned Gehrig heading down to spring training early amid rumors that the team was in the hunt for a right-handed first baseman,29 and Ruth reporting late after filming a movie, performing on the vaudeville circuit, and holding out for more money. Ruth had demanded as much as $150,000 and settled for three years at $70,000 per. (Gehrig, not yet a household name, was among the first to sign, for $8,000.)

When Ruth finally joined the team, he started slow. It was big news on Opening Day when Ruth removed himself from the lineup for a pinch-hitter, and he was fighting a cold. Two weeks in, he was batting .250 with just one RBI (a home run); Gehrig was hitting .459 and had already driven in 19. Then the weather started to heat up, and so did the Babe. What was less anticipated was that Lou wouldn’t cool. Throughout the summer, they traded shot for shot, Ruth going deep, then Gehrig. Whispers abounded about whether the King of Swing or the young usurper would make a run at Ruth’s record 59 home runs set in 1921.

But writers kept it in perspective. “Lou Gehrig isn’t another Babe Ruth because there will never be another Babe Ruth,” wrote Frank Graham in the New York Sun, “No one else has ever hit a baseball as far as the Bambino when he truly leans on it, and doubtless no one else ever will, nor has any other player ever had quite the color of the Babe. Yet Gehrig is the nearest approach to Ruth in modern baseball.”30

“There was just as much noise when Ruth struck out in the fifth as when Gehrig hit his home run with the bases full in the ninth,” wrote Rud Rennie of the New York Herald Tribune after a game in May. “They don’t pay to see Gehrig hit ’em.”31

“Gehrig, of course, cannot approach Ruth as a showman and an eccentric,” wrote Paul Gallico. “Right now he seems devoted to fishing, devouring pickled eels, and hitting home runs, of which three things the last alone is of interest to the baseball public. For this reason it is a little more difficult to write about Henry Louis than George Herman. Ruth is either planning to cut loose, is cutting loose, or is repenting the last time he cut loose. He is a news story on legs looking for a place to happen. He has not lived a model life, while Henry Louis has, and if Ruth wins the home run race it will come as a great blow to the pure.”32

Physically, they were a study in contrasts, too. Overindulgence often impeded Ruth’s staying in shape, and by 1927 his once tall and leanly athletic frame had developed the famed paunchy midsection that seemed to balance precariously on spindly legs. His face – the upturned nose, the wide grin – was cartoonishly recognizable. Gehrig, with his less distinctive All-American profile, appeared “much more the natural athlete,” wrote Robert Edgren of the New York Evening World. “His shoulders slope, his neck is long and thick, his arms are like an ordinary man’s legs, and his wrists and hands might make him a world’s champion knocker-out if he went in for boxing instead of baseball.”33

Even the way they hit home runs was different.

“When Babe Ruth knocks out a home run he puts everything, from his ankles to his ears, into the clout,” Edgren continued. “Babe follows through like a golfer. He uses every flexible muscle in his body, in his legs, and in his long arms.

“Lou Gehrig is a shoulder hitter. He takes a short chop at the ball. He is not a long swinger like Ruth.”34

“His powerful arms which extend from his more powerful shoulders enable Gehrig to hit to all fields without extra effort,” wrote Arthur Mann of the New York Evening World. “He is known as a stiff-arm swinger, in contrast to Ruth, who is the pivoting, free-swinging type. Ruth’s power comes from the tremendous swing and the fact that his timing is perfect. Gehrig does not swing his bat much. His arms and shoulders are so strong that when the bat meets the all it has about the same momentum as Ruth’s.”35

Fred Lieb of the New York Post recalled the press box being divided in 1927 – with Ford Frick, Bill Slocum, and Marsh Hunt rooting for The Babe, and Arthur Mann, Will Wedge, and himself rooting for Gehrig.36 As for the pair themselves, any rivalry between them for the title appeared at worst good-natured competition. Ruth called Gehrig “one of the finest fellows in the game.”37 Gehrig said of Ruth, “I get more kick out of seeing him hit one than I do from hitting one myself.”38

As late as September 5, the pair were tied with 44 homers apiece. Then Gehrig’s mother was hospitalized with an inflamed goiter. Surgery was required. Lou’s bat went cold; he hit just three more.

“I’m so worried about Mom that I can’t see straight,” Gehrig told Lieb. “If I lost her, I don’t know what I’d do.”39

Ruth, meanwhile, exploded, hitting 16 home runs in the Yankees’ final 24 games. The record-breaking 60th came on September 30, 1927, off the Senators’ Tom Zachary. “Sixty! Count ’em, sixty! Let’s see some other son of a bitch top that!” he famously said.

In the clubhouse after the game, he less famously said, “Will I ever break this again? I don’t know and I don’t care, but if I don’t I know who will. Wait till that bozo over there (pointing to Gehrig) gets waded into them again and they may forget that a guy named Ruth ever lived.”40

It was preposterous, of course, that “the guy who hit all those home runs the year Ruth broke the record” (as Franklin P. Adams of the Herald Tribune put it)41 would ever erase the memory of The Bambino, particularly with Gehrig’s final home run of the season a day later being anticlimactic and all but unsung. But it is a wonder Lou drove in a then-record 173 runs (Ruth held the record previously) when the Babe ensured that the bases were empty at least 60 times before Gehrig even got to bat. And altogether fitting that one of the few career offensive categories in which Gehrig bested Ruth was in RBIs per game (0.92 to 0.88). RBIs are the least heralded of the three traditional Triple Crown categories, not as readily tied to a player’s identity as his batting average and generally not as memorable as watching a ball fly 400 feet.

Gehrig also batted .373 (to Ruth’s .356), led the league in total bases (447) and doubles (52), and was second to Ruth in slugging percentage (.765). The accomplishments won him the American League Most Valuable Player Award … in part because Ruth did not qualify, as at the time no player could win it more than once.42

“If he keeps smackin’ ’em, he’ll be in the big dough,” Ruth said.43

Ruth had somewhat of a hand in boosting Gehrig’s image. In August Gehrig had parlayed his newfound fame into a contract with Ruth’s manager, Christy Walsh. It was Walsh who had booked Ruth’s numerous endorsements, organized his offseason exhibition and entertainment schedule, created a trust fund to house his income so The Bambino wouldn’t blow it all at once on broads and booze. That offseason, when Ruth embarked on a three-week, 21-city barnstorming tour across America, he took Gehrig with him.

They headed regional teams consisting of semipro, prep-school, or minor-league players, Ruth, the flashy batman with the magnetic personality, wearing the dark Bustin’ Babes uniform; Gehrig the shy boy wonder wearing the light Larrupin’ Lous. Sometimes they hit home runs; when they couldn’t, they took the mound trying to strike each other out. They signed pregame autographs, visited children’s homes, were feted by local Elks Clubs. Sometimes they gave speeches over the local airwaves, including a forgettable “comedy” routine (where the only thing worth laughing about was how uncomfortable they were reading lines).44 Ruth (.616, 61 hits, 20 home runs) was paid $28,281.93 for the trip. Gehrig (.618, 55 hits, 13 home runs) made $9,000 – more than his annual Yankees salary.45 He planned to give it all to his mother.46

Traveling around with Ruth was an education in celebrity. “Ruth taught me how to act while on parade,” Gehrig said. “We’d have been to jail more than once if Ruth didn’t know how to talk to traffic cops,” perhaps a reference to Ruth’s penchant for reckless driving.47

“You’ve got to be careful who you talk to and what you say,” Ruth told him.48

When they met the governor of New Jersey in Trenton, Ruth took the initiative to introduce Gehrig, who demurred. “The kid don’t say much,” Ruth said.49

Gehrig was so stiff, he was frequently the butt of Ruth’s jokes, too. Dining in transit, Ruth would ask for “steak a la Gehrig.” The incredulous serving staff would make sure they heard him right. “We never had a similar order, Mr. Ruth. Can you tell me how you want this steak?”

At which point, Ruth would deliver the punch line: “Good and thick, that’s how I want it. That’s steak a la Gehrig.”50

They both enjoyed card games on road trips and were often bridge partners. Teammate Bill Werber recalled Ruth slowly imbibing whiskey as he played to stay loose. “Ruth would start making bad bids just to aggravate Gehrig,” Werber said. It always worked – eventually, the stone-cold sober Gehrig would throw down his cards and stomp off in exasperation. Game over.51

Gehrig’s reluctance to take risks permeated into his salary negotiations; in spite of Ruth’s urging to hold out for what he was worth – when players had little bargaining power in the era of the reserve clause – Gehrig was often too eager to sign what was in front of him and hold onto his job. In contrast to Ruth, who, in spite of never being able to top his desired 100 grand a season, was able to legendarily brag about his Depression-era $80,000 salary being higher than President Hoover’s because he “had a better year.”

Before 1930, Ruth told Gehrig to hold out with him to give them a stronger position. Gehrig said, “I don’t think so,” and signed. Ruth biographer Robert Creamer said that “Ruth was always a bit contemptuous of him after that, as he was of Gehrig’s spending habits.”52 Teammates used to rib Gehrig about saving the first dollar he ever earned – which may not have been too far off. Later surfacing among Gehrig’s things was a postal savings certificate for exactly one dollar dated October 1, 1914, when he was 11 years old.53

“Surely Babe was ridiculous when he left a ten dollar tip where fifty cents would have been generous. But Lou’s dimes were just as silly,” said Claire Ruth.54

Still, there were times when Gehrig gladly followed Babe’s lead. A particularly raucous celebration on the train back from St. Louis after the Yankees’ back-to-back World Series win in 1928 saw Babe and Lou going after people’s shirts, culminating with Gehrig crashing through the door of Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert’s compartment and fighting with Ruth for the Colonel’s lavender pajama top.55

They developed their own code for dealing with the public on barnstorming trips – when one of them tired of speaking with fans, he would drag his finger along his sleeve like sharpening a razor – the visitor had become a “barber”; cut him. The other one would then create a diversion to break up the conversation.56

They went hunting and fishing together (with an oft-circulated photo showing off their catches – The Babe, naturally, has two fish on the line to Gehrig’s one). Gehrig took golf lessons in an attempt to join Ruth in one of his favorite pastimes, until he discovered it was cramping his swing.57 Ruth became a frequent dinner guest of Mom and Pop Gehrig, who bonded with him because he could converse in their native German. One day he gifted them a Chihuahua, and Mom Gehrig named it Jidge, a corruption of “George,” which Ruth’s clubhouse and card-playing buddies sometimes used.

Ruth brought his adolescent daughter, Dorothy, in tow so often that she had her own room in the Gehrig house, and considered them her “second family.” Searching for “motherly attention,” she became close with Mom Gehrig, who looked upon Dorothy as the daughter she never had the opportunity to raise. Dorothy also used to watch Lou shave before he left for the ballpark.

“What young girl wouldn’t have had a crush on New York’s most eligible bachelor?” Dorothy said.58

When Ruth’s estranged first wife, Helen, died in a fire in the winter of 1929, Gehrig sent him a letter of “heart-felt sympathy,” addressing Ruth as “George.” He wrote, “May the Almighty grant you and Dorothy sufficient strength to bear up during your bereavement. Your sincere friend, Lou Gehrig. Key West, Florida, where happiness reigns on a fishing trip I wish you shared.”59

Meanwhile, on the diamond, Gehrig couldn’t even claw himself from Ruth’s shadow when he tried. On April 26, 1931, he had a two-run home run called back when teammate Lyn Lary, thinking the ball had been caught, didn’t circle the bases. At the end of the season, it cost him sole possession of the home-run title – he and Ruth finished tied with 46 apiece. On June 3, 1932, Gehrig became the first modern player to hit four home runs in a single game (something Ruth would never do) – but had the fortuitous timing to do it the day popular Giants manager John McGraw announced his retirement, costing him top billing on the sports pages. In both the 1928 and 1932 World Series, Gehrig’s accomplishments took a backseat to Ruth’s singular feats. In the former, Gehrig batted .545 with four home runs; Ruth batted .625 with another three-home-run game. And in the latter, history remembers Ruth’s alleged “Called Shot” in Game Three, but mentions less often that Gehrig also hit two home runs in that game (and batted .529 in the Series).60

“Let’s face it. I’m not a headline guy,” Gehrig once said. “I always knew that as long as I was following Babe to the plate I could have gone up there and stood on my head. No one would have noticed the difference. When the Babe was through swinging, whether he hit one or fanned, nobody paid any attention to the next hitter. They all were talking about what The Babe had done.”61

According to wife Eleanor Gehrig, although Lou was amused that Ruth “could have five affairs in a night,” he was annoyed that Ruth could “get away with all the things he did and remain on top.” For Lou, living large wasn’t the type of fame he wanted.62

The “feud” between Gehrig and Ruth is often simplistically attributed to a dispute arising from Mom Gehrig’s offhanded comment about Claire Ruth not dressing her stepdaughter, Dorothy, as nicely as her biological daughter, Julia. An offended Claire relayed the remark to her husband, who confronted Gehrig about it. “Tell your mom to mind her own business!” Ruth said. Well! Nobody insulted Lou’s mother! And the two supposedly never spoke again.

It wasn’t that straightforward, and the cracks were numerous.

Lefty Gomez, a teammate starting in 1930, claimed that much of the Ruth-Gehrig rift was inflated rhetoric. “You keep hearing these stories about Babe and Lou not hitting it off,” he recalled.

“When you consider ballplayers are together from February until October, there are going to be squabbles. But Babe and Lou enemies? Not a chance. Babe was an extrovert in the extreme and Lou was an introvert. Babe threw his money around and Lou counted his pennies. Babe liked the high life and Lou enjoyed the opera and the philharmonic. Babe was glib with the press; Lou found it hard to come up with a snappy quip. There may have been comments here and there that caused temporary chagrin, but Babe and Lou were teammates and friends on and off the field. The press created a feud between Ruth and Gehrig that I never saw. Babe and Lou were both dear friends of mine as well as teammates, and I respected the fact that they lived life their own way. Nothing more, nothing less.”63

Tension between the two more likely arose from Ruth’s decline and ensuing frustration, at the same time as Gehrig found his voice and his identity.

Early signs of frigidity between the pair began to show in 1931, with the hiring of Joe McCarthy to manage. The Babe had thought he would be in line for a managerial position after retired teammate Bob Shawkey had been chosen following Huggins’s death in 1929, so he resented the new manager from the beginning. McCarthy could be a disciplinarian – imposing a dress code and more rigorous conditioning requirements – and Gehrig appreciated his high expectations. The childless McCarthy saw Gehrig as the surrogate son he never had. The man-child Ruth, who spurned authority, could not adapt.

One night after losing a hand at bridge, Ruth remarked that he’d “butchered that one just like McCarthy handles his goddamn pitchers!” Gehrig bristled and told Ruth to control his mouth. The next day, he was still fuming; he complained to reporter Stanley Frank that Ruth popped off too “damn much,” and that he had a special obligation to respect the game.64

By the mid-1930s, Ruth was pushing 40, fed up, and itching to manage a team himself – an opportunity that famously would never come. Old, slow, and out of shape, in 1934, his final season with the Yankees, he took a $17,000 pay cut and had his worst year since he became a full-time hitter (.288, 22 home runs, 84 RBIs), apart from maybe the injury-laden 1925. He started and finished just 31 of the 110 games he played.

Gehrig, meanwhile, won the Triple Crown in 1934 – the first and only season he surpassed Ruth in homers. His marriage Eleanor Twitchell in 1933 had done wonders for his confidence; the more bold Eleanor honed his celebrity, encouraging him to engage with fans and advertisers and to demand from the Yankees what he was worth contractually. His image of clean living and durability, which previously had repelled writers in search of a colorful quote, had shaped him into a team leader; he would be appointed the Yankees’ captain in 1935.65 His obsession with not missing a day of work had turned him into baseball’s Iron Man – and he surpassed one-time teammate Everett Scott’s record by playing in his 1,308th consecutive game on August 17, 1933.

Gehrig found a way to emerge from Ruth’s shadow just as the shadow of Ruth was disappearing. Ruth played a fraction of a season with the Boston Braves in 1935, but he was little more than a sideshow and hung up his spikes by early June. A photo when the Yankees and Braves faced each other during spring training of Ruth and Gehrig perfunctorily shaking hands, exchanging concealed grimaces, tellingly showed how frosty their relationship had become.

The goodwill tour of Japan the previous winter – featuring Ruth, Gehrig, and 13 other American League stars – widened the rift. The pair must have been on speaking terms beforehand, as Ruth lent the stingy Gehrig $5,000 at the outset of the tour to last him until his paycheck.66 They played alongside each other, and there are few reports of the group being anything but laudable ambassadors for the game67 – and the Japanese went wild for Ruth.

But on the ship across the Pacific, something went wrong. It happened when Claire Ruth crossed paths one day with Eleanor Gehrig, Lou’s wife of about a year. They pooh-poohed whatever bad blood there was between their husbands, and Claire invited Eleanor back to their cabin. The Babe was waiting, and alcohol was involved. Innocent revelry may have been all that occurred.68 But Lou was worried sick that his new bride had disappeared for several hours, and The Babe was the source of his fury. Gehrig coldly blew off Ruth’s peace offering.69

Said 18-year-old Julia Ruth to a friend upon passing by Gehrig one day on deck, “Don’t stop. The Ruths don’t talk to the Gehrigs.”70

Wrote Eleanor Gehrig, “Their feud, their ridiculous new feud, didn’t diminish the team’s performance when it came to baseball; we simply went our separate ways, the Ruths and the Gehrigs. … It was silly, it was sad, that their final ‘road trip’ of any consequence should be queered by champagne, caviar and bruised feelings. But it was, and that’s life in the showcase, too.”71

Ruth gained more of Gehrig’s ire when he attacked what Lou nurtured most: the Streak.

“I think Lou’s making one of the worst mistakes a ball player can make by trying to keep up that ‘iron man’ stuff,” Ruth told the Associated Press in January 1937. “He’s already cut three years off his baseball life with it. He oughta learn to sit on the bench and rest. They’re not going to pay off on how many games he’s played in a row.

“The next two years will tell Gehrig’s fate. When his legs go, they’ll go in a hurry.”72

Incensed, Gehrig responded shortly afterward, careful not to mention Ruth by name. “I don’t see why anyone should belittle my record or attack it,” he said. “I never belittled anyone else’s. I’m not stupid enough to play if my value to the club is endangered. I honestly have to say that I’ve never been tired on the field.”73

Clearly, Ruth was bored. Golf kept him busy (“If it wasn’t for golf, I’d really miss baseball. I play 240 days out of the 365 now”74), and he could continue to pay his expenses simply by being himself – he bragged about the $1,500 he’d made recently appearing on the radio for five minutes. But he was still waiting for that phone call.

“I’m not interested in any business,” he said. “I’ve had all sorts of offers. One week in an office and I’d be dead. I’ve had a chance to go into the front office of a major league club, but I’m not interested. I need fresh air. If I can’t get a major league manager’s job, I’ll just take it easy. The minors are out.”75

The closest Ruth got to managing was in 1938, when he coached the Brooklyn Dodgers. General manager Larry MacPhail picked him up on a whim upon seeing the crowds he drew as a spectator at Ebbets Field in June 1938,76 offering him $15,000 for the balance of the season. There was never any promise that Ruth would succeed current manager Burleigh Grimes, but Brooklyn’s dismal 69-80 record and Ruth’s inability to get along with Grimes’s successor, Leo Durocher, ensured that he wouldn’t return.

Meanwhile, Gehrig, having surpassed 2,000 consecutive games, suddenly seemed on the decline. He still hit .295 with 29 home runs and 114 RBIs in 1938, but he went through prolonged slumps, and the ball didn’t have the same pop. The next year was even worse, and after a game on April 30, 1939, when teammates congratulated him on fielding a routine groundball at first base, he voluntarily benched himself.

Perhaps his legs were starting to go – but not due to exhaustion. The cause was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The publicly released statement called it “chronic poliomyelitis,” which masked its true effects – ALS is a degenerative neuromuscular disease that no one survives. The media simply reported it meant he was through with baseball.

“Just tell him I’m very sorry – deeply sorry,” said The Babe from the clubhouse of the Quaker Ridge Country Club, where he was participating in a golf tournament. “I certainly hope for the best. He certainly had a real career while it lasted.”77

The Yankees hastily organized a tribute for their fallen captain between games of a doubleheader on July 4, 1939. That was the day Gehrig through his tears proclaimed himself the “luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

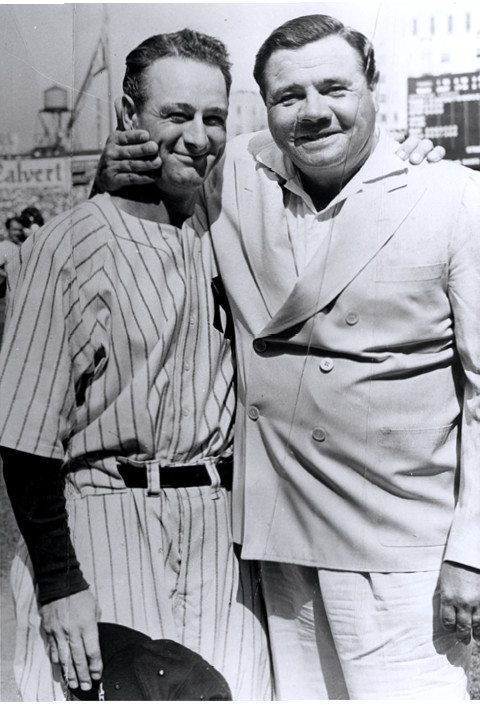

Dignitaries and former teammates, including Ruth, were invited to pay their respects. Gehrig applauded with the crowd over 61,808 as the Babe strode out in his white suit and took his place among the rest of the 1927 Yankees. “In 1927, Lou was with us, and I say, that that was the best ballclub the Yankees ever had,” Ruth jovially addressed the crowd.

The Babe concluded: “What I should think Lou would do – I don’t know if the club is gonna consider it or not – but my idea is to let Lou go up into the mountains – I saw a fishing rod here a minute ago – let him go up there and see if he can catch every fish there is.” They shook hands; Lou mouthed, “Thank you.”

The Babe put his arms around Lou in a giant bear hug – too often this moment gets cited as when their silly feud allegedly ended, but that feels overly simplistic – and the Babe whispered something in Lou’s ear that made Gehrig, solemn throughout the ceremonies, crack a rare smile.78

The Associated Press claimed Ruth told him, “C’mon kid, C’mon kid. Buck up now. We’re with you.”79

Bill Dickey, Gehrig’s best friend on the Yankees, claimed that Ruth and Gehrig were “never friends again” after all that had come between them, and this was clear on Lou Gehrig Day in particular, because “if you look close, Lou never put his arm around the Babe. Lou just never forgave him.”

Although his point about who hugged whom is belied by photographic evidence, his overall observation may not be completely out of left field. Gehrig, who stayed on as a nonplaying captain with the team through the end of the season, was photographed with Ruth in the Yankee Stadium dugout during the 1939 World Series (in which the Yankees won their fourth straight championship). But if the pair did meet afterward, it didn’t make the papers. Dorothy Ruth Pirone said in her memoir that Ruth did visit Gehrig “often” as his health deteriorated, over Claire’s objections.80 Though Ruth had his own health issues to contend with, having suffered two mild heart attacks within a year.

When Ruth learned of Gehrig’s death at age 37 on June 2, 1941, he broke down. “No, no … this is terrible, terrible news. It can’t be true,” he said. “I knew how ill Lou was, but I think all of us hoped, even against hope, that he would fight his way out.

“Lou was like a son to me. When illness forced him to retire, I was as heartbroken as he was. Believe me when I say his memory should always be kept green as an inspiration to all of us.”81

“I never knew a fellow who lived a cleaner life,” he said in another interview. “He was a clean-living boy, a good baseball player, a great hustler. He was just a grand guy.”82

Babe and Claire Ruth showed up to pay their respects at the church where Gehrig’s body lay in state.83 Holding back tears, as the Associated Press reported, he “brushed through a hundred fans who had trooped with him to the door of the church and who met him as he came out another door. Even in death, someone remarked, Gehrig shared the spotlight with his famous teammate.”84

A photo of Ruth standing forlornly beside Gehrig’s open coffin made the rounds in the press, but the word was that The Babe showed up visibly drunk at his teammate’s wake, angering especially Eleanor Gehrig. “He certainly wasn’t wanted by the Gehrigs, as there was friction between them for years,” wrote songwriter Fred Fisher, a friend of the family.85

Thus, a few months later, when Hollywood wanted to turn Gehrig’s life into Pride of the Yankees, Eleanor Gehrig objected to Ruth appearing in the picture “in the flesh. Feeling that he would make a further mess of baseball and ruin the beautiful tribute to Lou, who represented the clean side of the sport.”86 Eleanor, still very much in mourning, was afraid of Ruth’s gargantuan presence in life consuming her husband’s in death.

Christy Walsh believed otherwise: “To tell the life story of Lou Gehrig without some reference to Babe Ruth would be suicide from a box office or the critics’ standpoint,” he said, assuring Eleanor she’d have control over the nature of Ruth’s inclusion.87 The general compromise was that Ruth would appear only with the Yankees en masse, not by himself. It didn’t quite happen that way, but his role was limited enough to a supporting character in a film where Gary Cooper was clearly the star.

To appear in playing shape, Ruth crash-dieted to bring his weight down from around 270 to 223. A car accident, followed by an undisclosed illness that had him hospitalized shortly before shooting began, jeopardized his appearance. But he recovered in time to make it to the set to play a version of himself on the silver screen.

While Pride of the Yankees was a box-office success in 1942, The Babe Ruth Story, based on Ruth’s ghostwritten autobiography with Bob Considine, became a box-office joke. Released while Ruth was dying of cancer in 1948 (he showed up to the premiere doped up on meds and didn’t last 20 minutes), the film starring William Bendix was at best hagiographic, at worst –particularly when it tried to evoke the same pathos as the Gehrig story had – a mawkish mess.88

Ruth had two “farewells” at Yankee Stadium: the Yankees held a “Babe Ruth Day” on April 27, 1947, and Ruth’s cancer-ravaged figure trod out there in his famed number-3 uniform for the ballpark’s 25th anniversary on June 13, 1948. The sound bites aren’t as immediately recitable – Ruth’s tautological “The only real game, I think, in the world is baseball” on the latter date gets the most quoted – but the sentimentality was. That day, which included a pregame contest between retired players, also officially kicked off an annual Yankee Stadium tradition – Old Timers’ Day.

Ruth died two months later, on August 16.

Unlike Gehrig, who lay in state in two churches and whose funeral consisted of an under-10-minute ceremony in Riverdale before fewer than 100 intimates, Ruth in death was still attracting mayhem. His body was laid out at Yankee Stadium, where tens of thousands89 waited hours to catch one last glimpse of The Bambino. His funeral service at historic St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan featured 57 honorary pallbearers, the mayor and governor among them, 44 priests, and a packed house of 6,000.90

Less than two miles away from each other in Westchester County sit two adjoining cemeteries, Gate of Heaven, where Babe Ruth is buried, and Kensico, where Gehrig’s ashes rest. Fans make the pilgrimages, leaving flowers and all kinds of baseball paraphernalia.91

Their enshrinement in Cooperstown also fit their personalities. Ruth was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936 as part of the inaugural class, and was present for much fanfare as the museum opened for business on June 12, 1939. Gehrig, chosen by special election in December 1939, didn’t live to see an induction ceremony, which were held every two years at the time.

Their retired numbers – Gehrig first, in 1940, Ruth waiting until 1948 – sit side-by-side in left field at Yankee Stadium today. For years, their monuments also flanked each other as memorials (with Miller Huggins in between them) in fair territory at old Yankee Stadium – Gehrig’s erected in July 1941, Ruth’s in 1949 – and were moved to Monument Park upon the Stadium’s renovation in 1976, and relocation in 2009.

Gehrig’s monument says, “A man, a gentleman and a great ballplayer whose amazing record of 2,130 consecutive games should stand for all time.” (Cal Ripken Jr. was 19 years away from being born.) Ruth’s says simply, “A Great Ball Player, A Great Man, A Great American.” Note the dedications, though: Ruth’s, “erected by the Yankees and the New York Baseball Writers”; Gehrig’s, “a tribute from the Yankee players to their beloved captain and team mate.”

Both “great ballplayers,” yet who said it was what mattered. Everyone loved The Babe, but the media said it loudest; Gehrig quietly gained respect from those who knew him. Contrasting sentiments on two monuments of the same size.

TARA KRIEGER has regaled in telling stories about Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig since her ninth grade English teacher let her do a term paper on the 1927 Yankees. Although her current day job is as an attorney for the City of New York, she has previously been on staff as a sportswriter for Newsday and as an editorial producer with MLB Advanced Media. With SABR, where she has been an active member of the Casey Stengel chapter since 2005, she is an editor and contributor to BioProject and has participated in the publication of several SABR books, including Van Lingle Mungo, The Miracle Has Landed, Bridging Two Dynasties, Go-Go to Glory, Minnesotans in Baseball, No-Hitters, and Met-rospectives.

Notes

1 For much of his life, Ruth believed his birthdate to be February 7, 1894, a year older than he actually was. Gehrig was born on June 19, 1903.

2 Fred Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 176.

3 Two had in the NL: The Cardinals’ Rogers Hornsby hit 42 in 1922, and the Phillies’ Cy Williams hit 41 in 1923.

4 In spite of extensive research, Ruth’s RBI total is sometimes debated, as the RBI was not an “official” stat until 1920. For more research into Ruth’s RBI total, see generally sabr.org/research/accurate-rbi-record-babe-ruth.

5 Ted Williams is second, at .634.

6 Baseball-reference.com lists the top five as Williams (.482), Ruth (.474), John McGraw (.466), Billy Hamilton (.455), and Gehrig (.447). As Hamilton and McGraw played largely in the nineteenth century, a case could be made for Gehrig and Ruth actually being in the top three.

7 Ruth’s record-setting 60 homers were more than every other team in the American League and all but the Giants and the Cardinals in the National League; Gehrig’s 47 round-trippers outdid Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, and Washington in the AL, and three teams in the NL.

8 “Columbia Lou,” a reference to where Gehrig went to college, had some staying power, but it wasn’t uncommon then for sportswriters to repeatedly pick up on a ballplayer with any background in higher education—“Harvard Eddie” Grant being another notable example.

9 The plague of infant mortality hit both families hard. Gehrig grew up essentially an only child; Ruth had only a younger sister, Mamie, who survived babyhood (and would outlive him).

10 He was actually 17, but Ruth, along with many writers on the circuit, was prone to exaggeration. Jane Leavy, The Big Fella (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 265.

11 Ruth went 2-for-4 with a double that game; the day before – June 25 against Boston – he’d had his fourth two-homer game of the season.

12 The Chicago Tribune had singled him out as a player to watch, using the “Babe Ruth” moniker, on June 24, two days before the game took place.

13 The New York Times referred to “Gherrig”; the Chicago Tribune called him “Gherig”; the New York Tribune, “Cherrig.”

14 Also: “It was a blow of which any big leaguer would have been proud and was walloped by a boy who hasn’t yet started to shave.” James Crusinberry, “New York Preps Down Lane Tech in Hitfest, 12-6: Gherig Swats Homer with the Bases Loaded,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1920.

15 The scholarship was actually for football, which Gehrig also played for a season with Columbia.

16 Ray Robinson, Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time (New York: HarperPerennial, 1991), 58.

17 Robinson, 67-68.

18 Robinson, 68. Hoyt also retells the story with Ruth initially protesting, then thinking better of it: “I got others,” he said. See Gary Sarnoff, The First Yankees Dynasty (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland 2014), 50-51.

19 Regular first baseman Wally Pipp had injured his ankle.

20 Interestingly, the column to which such a phrase has been attributed, W.O. McGeehan’s “A Demigod Has Indigestion,” in the New York Tribune, does not quite use that phrase. McGeehan’s specific wording is, “It is not remarkable that the stomach ache of Babe Ruth was felt around the world.” McGeehan also called Ruth’s aliment “the stomach ache of a demigod,” and called Ruth “our own national exaggeration.” collection.baseballhall.org/PASTIME/demigod-has-indigestion-editorial-1925.

21 See Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, Pocket Books, 1976), 285-88. Author Jane Leavy also draws attention to reports the wound may have been a fistula, and that genetic intestinal diseases ran in Ruth’s family. Leavy, 271.

22 For a debunking of the alleged “headache” that kept Pipp from the lineup that day, see David Mikkelson, “Wally Pipp’s Career-Ending ‘Headache,’” Snopes, August 3, 2003, snopes.com/fact-check/wally-pipp39s-career-ending-39headache39/.

23 The 6-foot-2 Ruth shouted at the 5-foot-6, 140-pound Huggins, “If you were even half my size, I’d punch the shit out of you!” To which Huggins retorted, “If I were half your size, I’d have punched you.” Creamer, 292.

24 Before the suspension, Ruth hit .266 with 15 home runs and 36 RBIs over three months; after the suspension, he hit .346 with 10 home runs and 30 RBIs in four weeks.

25 Between 1920 and 1924 Ruth tallied .975 walks per game, or .217 per plate appearance; between 1925 and 1934, he had .844 walks per game, or .193 per plate appearance.

26 Meusel had led the AL in home runs and RBIs in 1925.

27 Sarnoff, 121-22.

28 The name was first bestowed on the 1921 squad, thanks to The Babe’s 59 home runs and the rest of the starting lineup hitting at least four apiece. G.H. Fleming, Murderers’ Row (New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1985), 95.

29 Monitor, New York World, February 20, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 38.

30 Frank Graham, New York Sun, June 25, 1927, reprinted inFleming, 229.

31 Rud Rennie, New York Herald Tribune, May 8, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 137.

32 Paul Gallico, New York Daily News, September 3, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 327.

33 Robert Edgren, New York Evening World, August 13, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 303.

34 Ibid.

35 Arthur Mann, New York Evening World, June 28, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 236.

36 Lieb, 174.

37 Richards Vidmer, New York Times, August 1, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 290.

38 Ford C. Frick, New York Evening Journal, July 2, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 250.

39 Lieb, 174-75.

40 Arthur Mann, New York Evening World, October 1, 1927, reprinted in Fleming, 359. Mann added, “If the world forgets a guy named Ruth lived, it will be due to universal amnesia.”

41 See Jonathan Eig, Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 103.

42 Using today’s metrics, had Ruth been eligible, it’s likely he would’ve edged Gehrig out. He had a higher WAR (12.4 to 11.8), and a higher OPS (1.258 to 1.240), though Gehrig slightly bested him in WPA (8.8 to 8.6). As it was, Gehrig only received seven of the eight first-place votes in 1927 – one went to teammate Tony Lazzeri.

43 Henry L. Farrell, “Babe Ruth Likes Prospects of Home Run Rival, Buster Gehrig,” Long Island Daily Press, August 18, 1927.

44 “‘Babe’ and ‘Lou’ (The Home Run Twins),” Perfect Record Company, 1927, youtube.com/watch?v=6p2WZufrzQk (last visited May 3, 2019).

45 In addition to these sums, Ruth made $3,000 modeling clothing, and the pair split $4,700 in “pickup” money. Leavy, 464.

46 Eig, 117.

47 Leavy, 123.

48 Leavy, 122.

49 Leavy, 87.

50 H.G. Salsinger, “I Remember Babe,” in Dan Daniel, The Real Babe Ruth (St. Louis: C.C. Spink & Son, 1948), 120-21.

51 Eig, 119.

52 Creamer, 382.

53 Robinson, 58.

54 Creamer, 382.

55 Frederick G. Lieb, “Life of Lou Gehrig,” published in The Sporting News’ Baseball Register (St. Louis: C.C. Spink & Son, 1942), 18.

56 Eig, 117.

57 Dorothy Ruth Pirone with Chris Martens, My Dad, the Babe: Growing Up with an American Hero (Boston: Quinlan Press, 1988), 105.

58 Pirone, 107. Dorothy reveals in her book that she was the product of her father’s affair with a family friend who she did not know was her mother until the woman was on her deathbed in 1980. As for the Babe’s two wives – Helen died before she was 8, and Dorothy had few positive things to say about her relationship with Claire.

59 Boston Herald, January 16, 1929, reprinted in Sarnoff, 200.

60 Gehrig is quoted as in awe of Ruth for “calling” his shot (“What do you think of the nerve of that big monkey, calling his shot and getting away with it?”), but also claimed Ruth was actually pointing at Cubs pitcher Charlie Root; from the on-deck circle, he overheard Ruth say, “I’m gonna knock the next pitch down your goddamn throat.”

61 lougehrig.com/quotes.

62 Richard Sandomir, The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and the Making of a Classic (New York, Boston: Hachette Books, 2017), 68.

63 Vernona Gomez and Lawrence Goldstone, Lefty: An American Odyssey (New York: Ballantine Books, 2012), 184-85.

64 Robinson, 128.

65 Ruth had been appointed captain of the Yankees for all of five days in 1922. He lost the title after an altercation with an umpire and a fan led to a suspension.

66 Leavy, 413.

67 Creamer, however, mentioned an incident of Ruth getting overly agitated at Gehrig for showing up late to a morning event. Creamer claimed Ruth’s reaction caused Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack, who also managed them in Japan, to reconsider his plans to retire and let Ruth take over. Creamer, 383.

68 Rumors of an affair between Babe Ruth and Eleanor Gehrig are unsubstantiated speculation.

69 See Eleanor Gehrig and Joseph Durso, My Luke and I (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1976), 189-90. June O’Dea Gomez, Lefty’s wife, noted in her journal that she spent a night drinking with Claire Ruth and Eleanor Gehrig on the same Japan trip. Whether that was before or after the incident in the Ruths’ cabin is unclear. Gomez and Goldstone, 185.

70 Creamer, 383.

71 Gehrig and Durso, 190-91.

72 “Babe Ruth Discusses Gehrig, Dean, The 1937 Pennant Races – and Golf,” New York Times, January 27, 1937. No one could have any way of knowing how prophetic Ruth’s words were – Gehrig had just about two seasons left in him, but playing every day wasn’t what brought him down.

73 Robinson, 224. Gehrig would keep his word, voluntarily removing himself from the lineup when he could no longer play.

74 “Babe Ruth Discusses Gehrig, Dean, The 1937 Pennant Races – and Golf.”

75 Ibid. Ruth had been offered the job of managing the Yankees’ Newark farm club in 1934, but felt it a slap in the face. “Why should I have to go down to the minors first? Cobb and Speaker didn’t,” he said referring to Hall of Fame player-managers Ty and Tris. See Creamer, 376.

76 The headline that day was Johnny Vander Meer’s second of back-to-back no-hitters.

77 Stanley Frank, “Gehrig Has Chronic Infantile Paralysis; Active Career Over,” New York Post, June 21, 1939. The Post indicated Ruth may have found out about Gehrig’s predicament the night before and played poorly in the tournament as a result.

78 Depending on which account of the events one reads, the embrace happened either before Gehrig’s oratory, as a means of encouragement, or afterward, as a parting shot.

79 “Ruth’s ‘We’re With You, Lou’ Keynotes Tribute to Gehrig,” Associated Press, Buffalo Evening News, July 5, 1939.

80 Dorothy does not say why Claire was against her husband visiting, though Dorothy spends much of her memoir speaking unfavorably of her stepmother. Dorothy also wrongly asserts her father visited Gehrig in the “hospital,” when Gehrig was generally homebound as his illness progressed. Pirone, 112.

81 “Babe Ruth Cries When Informed of Death,” International News Service, Syracuse Journal, June 3, 1941.

82 “Passing of Gehrig Mourned by City,” New York Sun, June 3, 1941.

83 Eig claims that Babe and Claire Ruth were actually the second mourners – after general manager Ed Barrow and his wife – to arrive, lending credence to the fact that the two had mended fences. Eig, 356.

84 Gayle Talbot (Associated Press), “Final Simple Rites Held for Iron Man of Baseball,” Auburn (New York) Citizen Advertiser, June 3, 1941.

85 Ray Robinson, “Ruth and Gehrig: Friction Between Gods,” New York Times, June 2, 1991.

86 Sandomir, 67.

87 Sandomir, 66-67.

88 A subsequent effort at a cinematic adaptation of Ruth’s life, The Babe (1992), went too much in the other direction – with John Goodman portraying Ruth as a fat, angry, gluttonous buffoon – and is largely unwatchable. A television film, Babe Ruth (1991), starring Stephen Lang, did an adequate job, but if not for the other two films of its genre being so terrible, would be otherwise unremarkable.

89 Jane Leavy estimates that as many as 77,000 filed past Ruth’s coffin. Leavy, 471-72.

90 Seventy-five thousand people were waiting outside as the hearse pulled up. Leavy, 472, 474-75; contrast with Gehrig’s funeral where a mere 250 fans stood outside the half-full Christ Episcopal Church in Riverdale. SeeAssociated Press, “Simple Rites Mark Funeral Services for Lou Gehrig,” St. Petersburg Times, June 5, 1941. news.google.com/newspapers?id=UeNOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=X00DAAAAIBAJ&pg=2384,7032962&dq=gehrig&hl=en.

91 See, e.g.,Corey Kilgannon, “Where Babe Ruth Still Draws Fans (and Liquor, Cigars, and Hot Dogs),” New York Times, October 5, 2018, nytimes.com/2018/10/05/nyregion/babe-ruth-grave-yankees-red-sox.html.