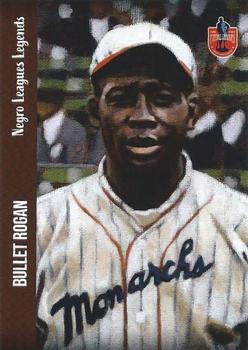

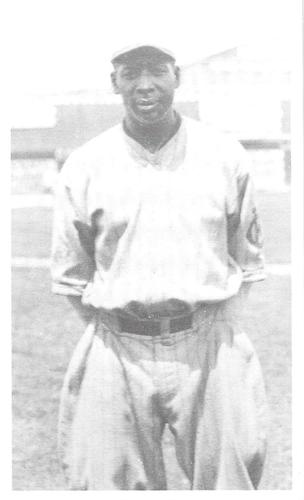

Bullet Rogan

“I have never seen a pitcher like him, and I have caught some of the best in the business.” – Frank Duncan1

“That Rogan can beat you, even when you pitch around him.” – Candy Jim Taylor2

How good was Bullet Rogan, also known as Bullet Joe Rogan? If the baseball gods were kind, the names Babe Ruth, Shohei Ohtani, Martín Dihigo, and Bullet Rogan would be inextricably bound as the best two-way players ever. According to Neil Paine, MLB writer, “[there was] another player that essentially did what Ohtani is doing right now—Bullet Joe Rogan of the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1920s and ’30s.” In fact, wrote Paine, “Ohtani is joining a club that Bullet Rogan founded.”3

How good was Bullet Rogan, also known as Bullet Joe Rogan? If the baseball gods were kind, the names Babe Ruth, Shohei Ohtani, Martín Dihigo, and Bullet Rogan would be inextricably bound as the best two-way players ever. According to Neil Paine, MLB writer, “[there was] another player that essentially did what Ohtani is doing right now—Bullet Joe Rogan of the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1920s and ’30s.” In fact, wrote Paine, “Ohtani is joining a club that Bullet Rogan founded.”3

The Oklahoma Historical Society cites Charles Wilbern4 Rogan’s birth date as July 28, 1889. And his Baseball Hall of Fame player file completed by his son after Rogan’s death also noted the 1889 birthyear.5 However, Phil Dixon’s exhaustive research and US Federal Census records definitively point to 1893 as Rogan’s year of birth in Oklahoma. He was the son of parents Richard and Mary, who also had a second son named Willard, four years Rogan’s junior.6 His mother died in 1900 when Rogan was still a boy, after which his family relocated to Kansas City. Rogan’s father Richard remarried, and Rogan grew up in a blended family with stepmother Ophelia’s two children. A troubled household with this family foreshadowed Rogan’s eventual, acrimonious departure from his home a few years later.7

Exposed as a youth to Kansas City’s semipro teams, the Giants, and then the Monarchs, Rogan was drawn by the allure of baseball. His interest was likely spurred in 1909, when Rube Foster and his Chicago Leland Giants came to town for a series against the Kansas City Giants in which the locals prevailed three games to two. Dixon offers the following insight into Rogan’s emerging love for baseball. “When Rogan decided to emulate his idols [on the Giants] and become a professional baseball player himself, no one, including his own stepmother, took him seriously. Rogan had never demonstrated natural talent, and he didn’t even look like a ballplayer. He possessed scrawny legs and an even narrower waist. The only part of his body that looked remotely athletic was his exceedingly broad shoulders. At 5-foot-7 [and around 175 pounds], it didn’t appear that he was going to grow to be a very large man either.”8

Rogan attended Sumner High in Kansas City from September 1908 to June 1910.9 While in school Rogan tried out for and joined the Palace Colts, a Black team owned by Fred Palace, who recruited teenagers from greater Kansas City to play both local and regional opponents of all colors. Rogan’s potential later led to him signing with his beloved KC Giants for a stint in 1911. That autumn Rogan enlisted in the 24th Infantry, stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

Jerry Malloy’s research on Black Baseball in the US military sets the context of what Rogan signed up for. After the Civil War, the Army created four African American units; the 24th and 25th Infantry, and the 9th and 10th Cavalry.10 In those postwar years baseball captured the nation’s fancy; the military was not immune. Wrote Malloy, “Colonel Andrew S. Burt decided to form a regimental team upon observing the hoopla of an informal game [of the 25th] at Fort Burford, North Dakota, in 1893.” The 25th Regiment was then based there. “The culmination of the Indian Wars gave African American soldiers the most recreational time they had ever known, and competition on the baseball diamond became fierce.” Among the four regiments, the 25th quickly “attained supremacy.”11

Rogan’s enlistment in the 24th coincided with Oscar Charleston’s.12 Oscar joined the 24th in Fort McDowell, California, in March 1912.13 Both ended up in Manila when the Regiment deployed to the Philippines14 and both became fixtures for the 24th’s baseball team.15 Rogan was in the 24th for three years and established a reputation as an outstanding ballplayer. Both the 25th Infantry and 9th Cavalry got wind of Rogan and enticed him to re-enlist. The 25th won the tug of war and Rogan recrossed the Pacific from California after his discharge to join the Regiment on Oahu. He immediately found himself at baseball’s Pacific epicenter.16

The intensity of play in Hawaii was fueled by a year-round season of multiple leagues and competitions. His Schofield Barracks-based 25th was not only competing against other military units but also had its own intercompany league. Further it was a fixture in the island’s Oahu League, comprising the better local teams. Added to that was an independent schedule with university and barnstorming squads from the mainland.

On the 25th team were several future Negro Leaguers, including Dobie Moore, Bob Fagan, Heavy Johnson, Lemuel Hawkins, and William “Big C” Johnson. However, from the outset, Rogan was the centerpiece. He caught for the 24th during his first tour, but his notoriety with the 25th stemmed from his pitching, complemented by his all-round play when not on the mound. He often got top billing in the local newspapers and the 25th’s regimental history noted of the team, “first of all there comes to mind Rogan, whose masterful pitching carried the regimental team to victory in many a tight game.”17

Upon his arrival in Hawaii in July 1915, the Honolulu Advertiser wrote, “The chief interest in the game was the first appearance on the local diamond of Rogan, late of the 24th Infantry, who arrived on the last transport … He looks like the classiest infielder the regiment has had in some time.”18 Stories and box scores soon carried references to Rogan as the 25th took on all comers. In October, in what must have been a surreal moment, Rogan caught for the 25th against his old team, the 24th, when the two locked horns during the 24th’s layover on its way to California from Manila. Rogan’s three-run homer in the bottom of the third assured the 25th of a 5-0 victory.19 His exploits at bat and in the field had already helped the Regiment win the Post championship in September and it dominated the Oahu League of local semipro clubs.20

The 25th realized how special Rogan was, opting to move him to the mound where his skills could best be used. The papers noted, “Rogan has switched from the backstop position to the mound, and in his two starts has shown enough to the fans to make him a big candidate for any pitching selection that might be made.”21

When it came to his moniker, Rogan’s Army nickname was not “Bullet.” A fellow soldier recalled that “it was ‘Cap,’ because, in the words of one veteran of the 25th, ‘in the army at that time a Captain was somebody and on the ball field Cap Rogan was somebody.’”22

The next year was a reprise of 1915; the 25th not only continued to defeat all comers but also gained the name that made it famous. In early 1916 the newspapers began to refer to the Regiment as the “wreckers union” and from June onward as the “Wreckers” or “Wrecking Crew.” Demolishing the opposition is what they did.23

In February 1917 the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers arrived on Oahu to play the locals. At the top of the list was the 25th and in their first two matchups, Portland lost by the scores of 3-0 and 4-1. Rogan tossed complete game victories in both, the first a two-hit, 13-strikeout performance. In the second game a few days later, “Rogan held the Portland Team to four hits.”24

Around this time Rogan took a three-month furlough stateside. Dixon noted that Rogan had family matters to deal with in Kansas City. On his way, Rogan stopped off to play in California, where his reputation preceded him. It was reported that baseball experts considered him “to be the greatest colored star in the game today.”25 He signed to pitch for the L.A. White Sox and did not disappoint, beating a local squad, 10-2, smacking three triples, and taking a no-hitter into the ninth inning before yielding a lone single.26 He did the same thing in K.C., throwing a two-hitter in a 1-0 victory.27 He returned to the Regiment in June, continuing to serve on Oahu until August 1918, when the 25th was reassigned to Nogales in southern Arizona in response to border unrest. In his three years of service in Hawaii, Rogan was the team’s lodestar. Adam Darowski’s review of available box scores reveals that in four years, Rogan is recorded to have pitched in 50 games, starting and completing 35 while compiling a record of 36-3. In 113 games, he batted .356 and slugged .651.28

On June 29, 1920, Rogan was honorably discharged from the service, just shy of his 27th birthday.29 His Army time was a vital prologue to his Negro Leagues career. It honed his style of play: great skill embodied in a tough, disciplined manner. One wonders if, according to Negro Leagues historian John Holway, “Rogan may have reached the pinnacle of his abilities out there and in the Southwest, far from big cities and the newspapers that would have insured his fame.”30

On July 4, 1920, he debuted with the Monarchs in the Negro National League’s inaugural year. Casey Stengel is often given credit for drawing Rogan to Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson’s attention.31 However, as previously noted, family matters had taken Rogan to Kansas City in 1917 while on leave. While there, he pitched for a local team against Wilkinson’s All-Nations squad, and it was then that Rogan first caught Wilkinson’s attention. Wilkinson signed Rogan to play for the All-Nations in the outfield and to pitch until his furlough ended.

On July 4, 1920, he debuted with the Monarchs in the Negro National League’s inaugural year. Casey Stengel is often given credit for drawing Rogan to Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson’s attention.31 However, as previously noted, family matters had taken Rogan to Kansas City in 1917 while on leave. While there, he pitched for a local team against Wilkinson’s All-Nations squad, and it was then that Rogan first caught Wilkinson’s attention. Wilkinson signed Rogan to play for the All-Nations in the outfield and to pitch until his furlough ended.

The seed was planted, and Wilkinson offered Rogan a contract to join the Monarchs after his discharge. In May 1920 the Kansas City Sun wrote that pitcher Rogan is expected shortly, and that “With John Donaldson and Sam Crawford … and Rogan, the best pitcher in the regular army, the Monarchs have a staff that will win many a game.”32

After his discharge, Rogan traveled to St. Louis to appear in his first game as a Monarch, against the Stars. He went 1-for-4 in a 4-2 Kansas City victory. On the following day, in Chicago, he came of age. In a one-hit performance, Rogan stopped the Giants after they had won six straight games.33

Rogan won seven games in his first partial season, including games against Chicago, Detroit, Indianapolis, and Dayton. In the offseason, his Monarchs defeated Babe Ruth’s Traveling All Stars, 10-5.34 Rogan played with the Los Angeles White Sox in the California Winter League in 1920-21, alongside fellow Monarchs Rube Curry, Hurley McNair, Dobie Moore, and George “Tank” Carr.35 It was at this time that Rogan picked up the nickname “Bullet,” probably due to his excellent fastball.36 The nickname transferred to Kansas City when Rogan returned to the Monarchs in the spring of 1921.37 It wasn’t until the summer of 1921 that newspapers started to occasionally refer to him as “Bullet Joe,” possibly a nod to a white major leaguer named Bullet Joe Bush, a hard-throwing righthander with the A’s and Red Sox.38

In his first four years with KC, Rogan became the star that his 25th Infantry career portended. Rogan went 7-5, 16-8, 14-8, and 16-11, for a total of 53-32.39 In 1921 he led the NNL in ERA, and one game in particular stands out, his 10-1 victory over the champion Chicago American Giants on July 4, 1921. Rogan contributed to the offense while giving up only a single tally in the eighth, pitching to new batterymate Frank Duncan (just acquired from the American Giants).40 In 1923 he led the NNL in wins, games started, complete games, innings pitched, and strikeouts. His batting kept pace with the high standards set by his pitching: he hit .296, .305, .369, and .363 with an OPS of 1.113 in 1922 and .967 in 1923. He played wherever needed when not on the mound. On August 5, 1923, Rogan joined forces with José Méndez to throw a combined 7-0 no-hitter against the Milwaukee Bears in Kansas City. Wrote the Kansas City Journal, “The hitless contest was the second of the twin bill. Mendez hurled five innings, retiring 15 batters in order. He then turned the job over to Rogan who walked a batter in the sixth, the only visiting player to reach first base.”41

The Chicago American Giants topped the standings in the first three years of the NNL (1920-22), with the Monarchs finishing third, third, and second—but in 1923, KC hit on all cylinders with a 54-32 record, finishing 3½ games ahead of the American Giants. The 1923 club was stacked with hitting—Heavy Johnson, Dobie Moore, Hurley McNair, Wade Johnston—and had a solid rotation led by Rube Curry, Bill Drake, and José Méndez. Rogan excelled in both facets. He not only led the league with 16 wins, but playing outfield when he wasn’t pitching, he was second on the Monarchs only to Heavy Johnson in on-base percentage (.416) and slugging (.551).

With the formation of the Eastern Colored League in 1923, the landscape of Negro League ball now included circuits in the East and Midwest. This made a “World Series” between the leagues’ pennant winners possible. The NNL and the ECL agreed to the first World Series in 1924 with Kansas City and Hilldale as contestants.42

The two sides battled in a 10-game series, with Hilldale holding an edge through the first six, 3-2, with one tie. In Game Seven, Kansas City prevailed, 4-3 in 12 innings on Rogan’s infield hit that scored William Bell.43 Game Eight featured a matchup between Rogan and his 1923 Monarchs’ teammate, Rube Curry. Both pitchers went the distance. With KC trailing 2-1 and batting in the bottom of the ninth, defensive lapses by Hilldale and a Duncan single drove in the winning runs in a 3-2 KC victory.44 Hilldale won Game Nine to tie the series. In Game 10, for all the marbles, José Méndez shut out Hilldale 5-0. For the Series Rogan batted .325 with seven RBIs, rivaled only by Judy Johnson’s .364 average and seven RBIs. On the mound, Rogan went 2-1, tossing three complete games.45

The winter of 1924 found Rogan in Cuba, playing for the Almendares Blues. His only season in Cuba46 was a successful one: the Blues won the title behind Rogan’s 9-4 record.47

When it came to Rogan’s pitching and hitting, his peers offered an up-close perspective.

- Teammate George Carr remembered, “He had not only an arm to pitch with, but a head to think with. … Once Rogan pitched to a batter, he never forgot the batter’s weaknesses and strong points.” 48

- Newt Allen agreed; comparing him to Satchel Paige, Allen wrote, “I give Rogan the edge, because he knew how to pitch.”49

- Catcher Frank Duncan had experience with both Paige and Rogan, “Bullet had a little more steam on the ball than Paige—and he had a better breaking curve.”50 Of Rogan, “he threw hard! He had everything, fork balls, spit balls, any kind of balls. And he had a master curve. He threw it right out of his palm. … He could throw it side arm and it would jump in on the righthanded batter.”51

- Chet Brewer said, “Rogan was the best pitcher I ever saw in my life.”52

Allen weighed in on Rogan’s hitting. “He was an awful good hitter, hit anything you threw … He was such a good hitter, he hit in fourth or fifth place in the line-up … and he could run fast; he was a ten-second man in the Army.”53 Duncan added, “Rogan was the best lowball hitter I ever saw, and one of the best curve-ball hitters.”54

The 1925 edition of the Monarchs was as good as, if not better than, the previous year’s team. Rogan led them to the first-half championship and then victory over the St. Louis Stars for the NNL pennant. If ever a year demonstrated his two-way prowess, it was 1925. He led the starting rotation with a 15-2 record and a 1.74 ERA. He led the NNL in winning percentage (.882), complete games (15), shutouts (4), and strikeouts (96). His .360 batting average and 1.016 OPS were both tops on the Monarchs. Complemented by the production of Dobie Moore and Hurley McNair, the team was a force to be reckoned with. In the seven-game series against St. Louis, Rogan won Games One, Four (a comeback win with Rogan driving in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth), and Seven, all complete games with the last a 4-0 shutout.55

KC anticipated affirming its dominance in the second Colored World Series, a best-of-seven tilt against Hilldale again. It was not to be. Rogan was hurt in a freak accident while playing with his son.56 He was ruled out of the Series and his Monarchs, lacking his starting pitching and timely hitting, fell to Hilldale in six games.

Rogan had a new assignment waiting for him in 1926. Wrote the Kansas City Call, “Wilbur (Bullet) Rogan, for five seasons a front string pitcher … and one of the best outfielders and hitters in the league, has been chosen by J.L. Wilkinson … to fill the position of manager left vacant by the resignation of Jose Mendez [due to health reasons] … the manager’s duties are not new to Rogan … He is the type of ballplayer who could best handle the club. His ability as a player is unquestioned and his disposition is agreeable, even when the tide is going against him … Rogan is the best man for the job.57

When it came to his managing style, player reflections varied. Holway wrote, “Rogan inspired confidence in his players and gave encouragement to his men. He was open minded, analytical, and courageous.”58 Dink Mothell, an NNL teammate, saw it differently. “Rogan wanted to run the ball club like they did in the army. He liked to give orders too much, even before he was managing. He used to bawl players out for different things.”59 Chet Brewer put it this way: “Rogan wasn’t the best manager because he was such a great player himself … He thought it should be easy for you. He didn’t know how great he was.”60

The Monarchs added a key piece in 1926—center fielder Cristóbal Torriente—and Chet Brewer, in his second year with the team, twirled a 12-1 record. While still superb at 12-3, Rogan’s ERA rose to 2.86, and his .809 OPS was his lowest since 1920.

Winning the first-half championship, the Monarchs turned in the best record in the NNL for the fourth straight year. In the NNL Championship Series Kansas City was pitted against second-half winner Chicago American Giants, the only barrier to their third straight World Series appearance. The nine-game series began well for Kansas City; Rogan appeared in relief in the first two games, winning both.61 The teams split the next two. Rogan prevailed against Bill Foster in Game Five, 11-5, but Chicago won the next two games, leading up to a series-deciding doubleheader with Chicago needing to win both games. In the first game, Rogan and Foster dueled for the third time. The contest was scoreless going into the ninth. Another leading Negro Leagues historian, James Riley, wrote, “The lefthanded Foster took the mound for the ninth frame and retired the side to continue his scoreless skein of innings. The righthanded Rogan took the mound in the bottom half of the inning and was within one out of matching Foster’s scoreless streak,” but then gave up the game-winning hit to Sandy Thompson. Series tied. In mythical form, both pitchers returned to start the nightcap, which was set for five innings “to enable the winning team to leave in time to make the opening game of the World Series in the east.”62 Actually Rogan had Brewer prepared to pitch the deciding Game 9, but when he saw the American Giants sticking with Foster, Rogan used his manager’s prerogative to take the ball himself. It was a mistake. While Foster shut out the Monarchs 5-0, Rogan had nothing left in the tank, giving up three runs in the first and two in the second on eight hits.63 Chicago then defeated the ECL champion Bacharach Giants to win the World Series.

With Rogan still at the helm in 1927, the Monarchs had another good year with a 55-33 record, but finished third in the NNL. Chicago won the first-half championship, defeated second-half winner Birmingham for the NNL title, and beat the Bacharach Giants in the World Series again. Rogan led the team in wins with 14, followed by William Bell’s 13. He hit .331 with a .895 OPS. The following year, Kansas City finished behind first- and second-half winners St. Louis and Chicago, respectively, with the Stars winning the championship. It was another well-rounded year for Rogan: .348/.405/.515 and 10-2 with a 3.24 ERA.

KC put it all together in 1929, finishing 12 games ahead of the St. Louis Stars and 17½ ahead of Chicago. The team won both halves and finished as NNL champions. Their roster was not that different, but they performed on all cylinders; Rogan, playing regularly in center field, finished with an OPS of 1.020 in 259 at-bats. What was different was Rogan opting out of the starting rotation; he pitched only three innings the entire NNL season. Monarchs’ starters William Bell, Chet Brewer, Andy Cooper, and Army Cooper all had double-digit wins.

The 1930 season was pivotal both for the Monarchs and Rogan himself. J.L. Wilkinson fostered the pioneering of a lighting system that the Monarchs successfully deployed that year, adding night games to their portfolio and opening the game to larger audiences, particularly those whose work schedules limited daytime attendance. But 1930 was also the first season played under the shadow of the Depression. For Rogan, an undisclosed illness took him away from the game for much of 1930.64

Wilkinson pulled the Monarchs from the NNL after the 1930 season and opted for an independent schedule over the next several years to ensure greater financial stability for the team. Rogan did not reappear in a KC uniform until late 1931, in a game against Grover Cleveland Alexander and the House of David. Rogan pitched the last inning, retiring the side, but in barnstorming games that year showed the rust that had accumulated during his illness.

The Depression was in full swing in 1932. Wilkinson balked at forming a team, but then reconsidered. By early summer the Monarchs were competing again. Rogan did not wait for Kansas City and began his comeback with Jamestown, a semipro team in North Dakota. Although 39, he was vintage Rogan in a microcosm and the Jamestown Sun wrote, “On August 14, in the final game on Jamestown’s schedule, Rogan hit a grand slam, drove in six runs, and pitched a six-hitter, defeating the Huron (South Dakota) Boosters, 9-3. It was Rogan’s 20th win, and raised Jamestown’s record to 32-7, including 25-6 at home.” Jamestown had won 11 of 12 from intrastate foes, prompting the Sun to crown Jamestown as the 1932 North Dakota champion.65

Rogan joined up as player-manager with the independent Monarchs after the end of Jamestown’s season, but not before he played a game against KC, handling first base for the North Dakota squad.66 The 1932 season ended with a Monarchs tour of Mexico in which Rogan won 14 games, and lost only two.67

Rogan was back with the Monarchs full-time in 1933 as its player-manager. The team declined to join the second incarnation of the NNL, instead playing an independent schedule. Rogan was only credited with playing five or six games against major league-level competition. For the season he hit well but pitched sparingly. Wrote Dixon, “1933 was one of the best seasons of his career … while it was assumed that Rogan had lost a step … taking into consideration his accomplishments of the season just past, he was still two steps ahead of nearly everyone else.”68

At the end of the season the Monarchs faced an All-Star team assembled by Dizzy Dean and, led by Rogan’s late-inning exploits, defeated them 5-4.69 Later Rogan joined the Philadelphia Royal Giants Goodwill Tour, one of the occasional trips to the Far East that promoter Lon Goodwin organized. Rogan joined several Monarchs teammates—Newt Allen, Chet Brewer, Andy Cooper, Dink Mothell, and Tom Young—for the tour lasting from mid-November to early April 1934.70 Bad weather precluded games in Japan and several were played in Shanghai, but Manila and Honolulu were the highlights. Upon the team’s arrival in Hawaii in March, the local papers lauded favorite son Rogan’s homecoming.71

Monarchs owner Wilkinson replaced Rogan as manager in 1934 with Sam Crawford. KC’s independent schedule included its entry in the Denver Post Tournament, where it reached the finals, losing to the House of David and “guest” pitcher Satchel Paige, 2-0. The Monarchs also played postseason tours against the aforesaid House of David and later, Dizzy Dean’s All-Stars (in six games, the Monarchs were 3-2-1).72

In 1935, with Crawford at the helm, Dixon wrote that “among [Crawford’s] first moves was to take Bullet Rogan out of the everyday outfield leaving him more available for” pinch-hitting and utility duty, “a role he filled relatively well.”73 The Monarch’s independent schedule took them to Portland, Oregon, where the local press wrote, “though he [Rogan] is well along in years … he can still turn in a creditable performance at any position on the diamond.”74

Nearly 43, Rogan returned to the Monarchs in 1936 under new manager Andy Cooper. He pitched more than in recent years and batted well, capably filling out a precious roster spot. With most of his playing career occurring before the inaugural East-West All-Star Game in 1933, Rogan appeared only once, in 1936. Per Retrosheet, Rogan started the game, made an out in the second inning, and left for a pinch-hitter in the fourth. 75

A year later, as Rogan played less and less, he participated in an October 10 game against Bob Feller’s All-Stars, who beat the Monarchs, 1-0. Rogan went 2-for-4 and stole a base, not wishing to be upstaged by his white opponents.76 In 1938 overtures to trade Rogan to the Detroit Stars were rebuffed by Wilkinson. His last game was in Chicago on September 4, according to Dixon, 18 years after his debut in the Windy City.77

In Cool Papas and Double Duties, another chronicler of Black baseball, William McNeil, wrote, “Like many of his compatriots, he [Rogan] usually played winter ball from October to March.”78 The California Winter League was Rogan’s go-to offseason baseball venue. In addition to playing for the champion Los Angeles White Sox in 1920-1921, he played for the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1925-26 and 1926-27, followed by a stint with the Cleveland Giants in 1928-1929 and then, in his last appearance, returned to the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1929-30. He amassed a 42-14 record in 64 games pitched and was the career leader in the CWL with 52 complete games. His 1925-26 season had him at the top of pitching charts.79 He also hit .326 while leading his team to the championship.80

That last year (1929-30) offered a unique matchup for Rogan and the Royal Giants. Rival local promoter Joe Pirrone signed Al Simmons and Jimmie Foxx to augment his All-Stars in a one-game contest with the Royal Giants. Despite the availability of Andy Cooper and Chet Brewer, Goodwin started the 36-year-old veteran, who scattered 10 hits interspersed with eight strikeouts in a 10-3 victory. Foxx went 3-for-3 against Rogan, but Simmons was hitless. Wrote McNeil, “Rogan was never faster in his life and the Stars merely blinked at many of his offerings as they streaked across the plate.”81 Rogan went 2-for-3 with two runs scored in his complete game victory.82

In 1938, at age 45, Rogan’s career ended. He played sporadically for the Monarchs, mostly in the outfield. Dixon chronicles Rogan’s swansong through the Midwest playing in venues that had been his stomping grounds over a nearly 20-year career. Like many baseball lifers, Rogan’s association with the game did not end when he hung up his uniform. Wilkinson employed Rogan as an umpire for Monarchs home games, a role he performed from 1946-50.83

After baseball, he worked for the Post Office, for which his devotion to duty was honored on his retirement on July 31, 1959.84 He and his wife Katherine (they had two children from their marriage, Wilber S. and Jean) lived in east Kansas City, where Rogan passed away on March 4, 1967.85 He was 73. In addition to his birth and death date, his grave marker in Kansas City’s Blue Ridge Lawn Memorial Gardens was modestly inscribed Arizona, SGT US Army, World War 1.86

In 1998—27 years after Satchel Paige was enshrined—the Hall of Fame finally inducted Rogan to Cooperstown. The politics and protocols of the Hall can be blamed for the delay. But nothing can deny the merit of his inclusion and it was with great grace that his son Wilber S. Rogan spoke on the family’s behalf at Rogan’s induction ceremony on July 26, 1998.

Said Wilber, “People ask me two questions when talking about my dad. One, where did he get the name ‘Bullet’ from? And who was the fastest—him or Satchel Paige? My answer to both questions is, I don’t know … But one thing I do know: When Satch was on the mound, he needed a designated hitter. When my dad was on the mound, he was in the cleanup spot.”87

How great was Rogan? Prominent Negro Leagues historian Larry Lester put it succinctly: “A no brainer … It’s criminal to think Bullet Rogan is not the greatest player of all time.”88

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Dana Berry.

Photo credits: Trading Card Database and SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

All statistics are taken from Baseball-reference.com or Seamheads.com, unless otherwise noted. A special thanks to Phil Dixon for his support and his outstanding research on Rogan.

Notes

1 “Meet Bullet Joe Rogan,” LA Dodger Talk, August 2, 2020. Last accessed on September 12, 2023.

2 Phil S. Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2006), 78 (hereafter, “Dixon”).

3 Neil Paine, “Only One Player Has Ever Been as Good as Shohei Ohtani,” FiveThirtyEight, June 30, 2021. Last accessed on February 12, 2021.

4 The 1910 Federal Census spells Rogan’s name Wilbern. He is listed along with his father Richard, younger brother Willard, stepmother Ophelia, and her children. Many subsequent references cite Rogan as either Wilber or Wilbur.

5 This earlier birthdate of four years is attributed to Rogan’s wish in his teens to come across as older than he was, perhaps in conjunction with his pursuing military service with one of the Black military units in the Midwest.

6 1900 US Federal Census. This Census lists father Richard and son Charles W along with Rogan’s younger brother Willard D.

7 Dixon, 11.

8 Dixon: 10.

9 Bullet Joe Rogan’s Player File at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

10 Jerry Malloy, “The 25th Infantry Takes the Field,” The National Pastime, Volume 15 (Society for American Baseball Research, 1995), 1.

11 Malloy, 1-2.

12 Negro Leagues historian John Holway, in his unpublished manuscript contained in Rogan’s player file with the Baseball Hall of Fame Library, wrote that “he ran off to join the army,” perhaps a consequence of his unhappy home life with his father and stepmother’s blended family. This quote did not make Holway’s published version of the Rogan chapter in Blackball Stars.

13 Jeremy Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 47.

14 “24th Infantry May Escort G.A.R.,” Buffalo Sunday Morning News, March 26, 1911: 20.

15 Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player, 45, 49-53.

16 Dixon: 16-17.

17 Dalbert P. Green,” History of the 25th Infantry Baseball Teams, 1894-1914,” in John H. Nankivell, editor, History of the Twenty-Fifth Regiment of United States Infantry, 1869-1926 (Denver, Colorado: Smith-Brooks Printing Co., 1927); reproduced by Negro University Press, New York (1969), 172.

18 “Third Battalion is League Leader,” Honolulu Advertiser, July 2, 1915: 12.

19 “More Diamond Fame for Twenty-Fifth Infantry, Army Champions of Oahu Outplay Stars of Twenty-Fourth with Large Crowds Cheering Both Sides,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 5, 1915: 12.

20 “Twenty-Fifth Infantry Wins Post Championship,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 23, 1915: 8.

21 “Travelers Will Meet 25th Team Next Saturday,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 15, 1915: 13.

22 Master Sergeant Bertran T. Beagle, retired, to “the Colored Baseball Hall of Fame’ – undated letter, Rogan File, Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

23 The Honolulu Star-Bulletin and Honolulu Advertiser abounded with 25th Infantry stories. “25th Infantry Takes Chinese Team into Camp,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, April 17, 1916: 12; “Ball Games for Today at Park,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 11, 1916: 14; “Santa Clara will be an Improved Team when they Meet the Wreckers,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 30, 1916: 12.

24 “Wrecking Crew Downs Beavers at Schofield,” Honolulu-Star Bulletin, March 1, 1917: 4.

25 “Wilbur Rogan, Star Utility Man, Signed by L.A. White Sox,” Los Angeles Evening Express, March 22, 1917: 21.

26 “Negro Hurler Mows ‘Em Down, Los Angeles Times, March 26, 1917: 7.

27 “Donaldson Will Pitch First Game Here Sunday,” Kansas City Post, April 26, 1917: 8.

28Adam Darowski has assembled a website with Rogan’s 25th Infantry statistics. Wilber “Bullet” Rogan: 25th Infantry Wreckers (darowski.com) Last accessed on January 31, 2024.

29 Malloy: 7.

30 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books ,1988), 172 (hereinafter, “Holway”).

31 According to Robert Creamer, Stengel “gathered a ragtag team of semipros and ex minor leaguers … on a barnstorming tour … one stop was Fort Huachuca … where they played a team of black soldiers that included a pitcher recalled as “Grogan” whom Stengel described as, next to Satchel Paige, the best colored pitcher I ever saw.” Stengel later mentioned Rogan to Wilkinson. Robert W. Creamer, Stengel: His Life and Times (New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1984), 129-130.

32 Untitled, Kansas City Sun, May 1, 1920: 12.

33 Dave Wyatt, “Rogan Stops the American Giants,” Chicago Defender, July 10, 1920: 9.

34 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 173.

35 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002), 74-75.

36 “Bobby Meusel to Hold Down First Against Sox,” Los Angeles Record, November 6, 1920: 14.

37 “Monarchs Open Season May 5,” Kansas City Star, March 27, 1921: 18A.

38 “Indianapolis Defeats Monarchs in Last Game,” Kansas City Journal, June 2, 1921: 8. “Beat Monarchs in Ninth,” Kansas City Star, October 16, 1921: 13; “Colored Cue Parlor,” Kansas City Kansan, December 24, 1921: 6.

39 These stats are according to Baseball Reference, which tracks NNL games separately from non-League contests. Over the same four-year period, Seamheads has him at 7-6, 16-11, 15-8, and 17-11, for a total of 55-36.

40 “American Giants Drop Two Games to Kay Sees, Monarchs Take Both Morning and Afternoon Tilts on Fourth of July,” Chicago Defender, July 9, 1921: 10. “Chicago Giants to Play Rube Sunday,” Chicago Whip, June 18, 1921: 7.

41 “Two Monarch Hurlers Hold Team Hitless,” Kansas City Journal, August 6, 1923: 5.

42 Q.J. Gilmore, the business manager of the Kansas City Monarchs wrote in the September 6, 1924, Chicago Defender, “There has been considerable agitation on the part of the base-ball fans throughout the country for a series of games to determine the Negro championship of the world between the winners of the pennant in the National Negro Baseball League and the Eastern League … On behalf of the Kansas City Monarchs, winners of the 1923 pennant, and the prospective winner of the 1924 National Negro League, I hereby issue a challenge to the winner of the Eastern League pennant for a series of games to determine the Negro world’s championship.” Larry Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2006), 29 (hereinafter, “Lester”).

43 Lester, 141-161.

44 Lester, 163-167.

45 Lester, 170-181.

46 A few player reminiscences among Rogan’s peers refer to more than one trip to Cuba, but no records are yet available to confirm such trips other than in 1924-1925.

47That winter Rogan famously struck out Alejandro Oms, Cuba’s legendary hitter who played for Santa Clara. Chet Brewer recounted that “Rogan threw Oms a drop ball, an overhand breaking ball. Oms left the ground. His cap came off, swinging at it. Rogan threw him two more and walked away. Oh, he could throw that ball.” Holway, Blackball Stars, 178.

48 “Wilber “Bullet” Rogan: A Bullet-Proof Case,” Rogan File, Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

49 Holway, 167.

50 Holway, 168.

51 Holway unpublished, 5. Rogan File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

52 Holway, 167.

53 Holway unpublished, 5. Rogan File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

54 Holway, 169.

55 1925 NNL Playoffs (retrosheet.org). Last accessed on January 6, 2024.

56 Dixon, 58.

57 “Bullet Rogan to Manage Monarchs: Mendez Hands in His Resignation,” Kansas City Call, March 12, 1926: 6.

58 Holway, 170. Not surprisingly, given Rogan’s nine years in the army, C. Johnson reflected on what was his aloof manner – “Rogan looked like a soldier, his deportment, his carriage.” Holway, 171.

59 Holway, 179.

60 Holway, 179-180.

61 Retrosheet is conflicted on whom to award the Game One victory to, identifying Rogan as the winning pitcher in one place, and Chet Brewer in another. Brewer started the top of the sixth when Chicago scored three runs to tie the game and Rogan came in after two batters, allowing an inherited runner to score and then two more on his own watch. At 3-3 in the bottom of the sixth, Kansas City scored the final run of the game on a single by Mothell driving in Torriente and held on for 4-3 victory. Rogan closed out the game.

62 Riley, 83-84.

63 Riley, 85; Thomas Kern and Bill Staples Jr., “Chet Brewer,” SABR BioProject, 2023: citing Holway, 210-11 and Dixon, 64.

64 Dixon notes that lockjaw, a virus, or an eye problem were among the most likely maladies. A private man, Rogan stayed away from the game for more than a year until he recovered sufficiently to resume play. Dixon, 100.

65 “Team Defeated Only 7 Times in 1932 Season,” Jamestown Sun, August 15, 1932: 6. Other accounts of Rogan’s tour with Jamestown differ when it comes to his stats. In his time with Jamestown, Rogan compiled a 20-3 record. When he was not on the mound, Rogan played the outfield or first base, and in 39 games he hit .315 with 11 home runs, and a team-leading 51 runs batted in. This from Thomas E. Merrick, “Jamestown, North Dakota, in 1932: Racial Reconciliation, and Hall of Fame Competition,” The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues (Phoenix, SABR, 2022).

66 Dixon, 110-111.

67 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson, and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2016), 86.

68 Dixon, 121.

69 “Rogan’s Hit to Right Breaks Up a Ball Game that Almost Gives Fans Heart Disease,” Kansas City Call, October 6, 1933: 2B. Kansas City defeated other teams of American and National League stars later that month, again led by Rogan’s hitting. “Big Leaguers with Paul Waner, Larry French, Glenn Wright, Lose to Monarchs,” Kansas City Call, October 13, 1933: 5B. “Monarchs Down Big-League Stars; Win 3 to 2 in Ninth,” Kansas City Call, October 20, 1933; 4B.

70 Kazuo Sayama & Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (Fresno, California: Nisei Baseball Research Project Press, 2019), 328-329.

71 “Crack Negro Outfit Here for Games,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 3, 1934: 8.

72 Dixon, 148-149.

73 Dixon, 152, 154.

74 “Kansas City Monarchs play here this evening,” Tacoma News Tribune, July 8, 1935: 7.

75 Lester, 80-82.

76 Dixon, 177.

77 Dixon, 180.

78 William F. McNeil, Cool Papas and Double Duties (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2001), 205.

79 Rogan led the League with 18 games and 153 innings pitched, 16 complete games, a 14-2 record, and 82 strikeouts. McNeil, 269.

80 McNeil, 112.

81 McNeil, 138.

82 Sayama & Staples Jr., 152-153.

83 Dixon, 183.

84 A certificate of Honorary Recognition from the Post Office Department noted, “This citation, tendered upon the occasion of retirement from active duty, conveys official commendation from the Postmaster General and cordial expression of esteem from coworkers in the Service.” Post Office Department, Rogan File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

85 Rogan and Katherine were married on October 19, 1922. She passed away in 1971.

86 Wilbur “Bullet” Rogan (1893-1967) – Find a Grave Memorial. It has since been supplemented by a larger marker memorializing his Negro League career. The Oklahoma Historical Society also placed a marker outside the Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark as part of Oklahoma’s 2007 Centennial. See: Wilber Joe Rogan Historical Marker (hmdb.org)

87 From Wilber S. Rogan’s speech in honor of his father’s induction in the Baseball Hall of Fame, July 26, 1998: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVbZtNq-aQs. Last accessed on January 6, 2024.

88 McNeil, Cool Papas, 183.

Full Name

Charles Wilber Rogan

Born

July 28, 1893 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

Died

March 4, 1967 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.