Baker Bowl (Philadelphia)

This article was written by Seamus Kearney

Why would you ever call it

Baker Bowl,

When all Baker did

Was despoil its

Soul!

— Seamus Kearney

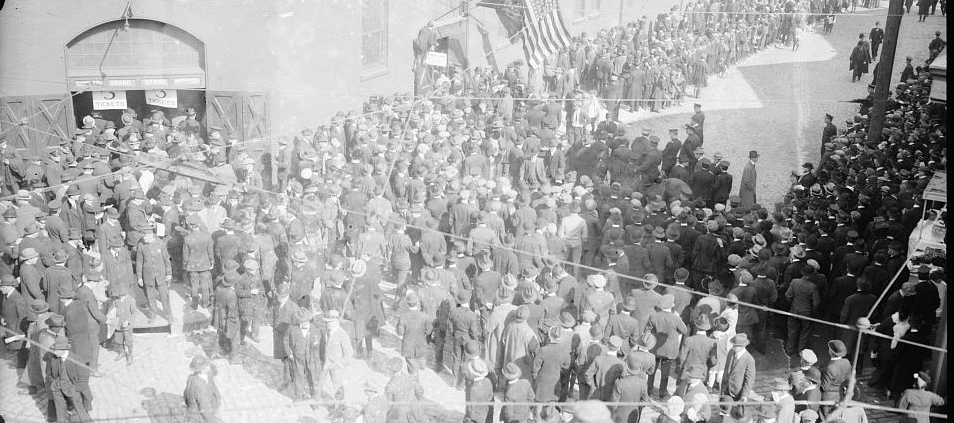

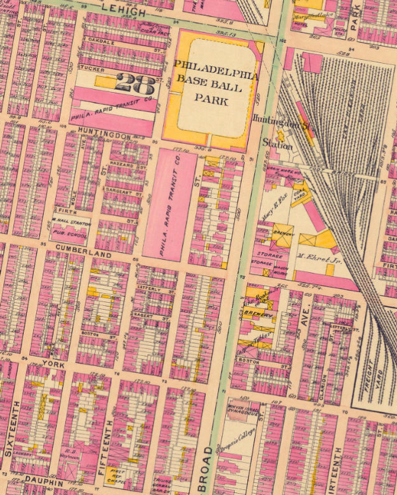

Fans enter the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, circa 1915. (Library of Congress)

The Philadelphia Base Ball Grounds, a.k.a. National League Park, a.k.a. Baker Bowl, the home of the Philadelphia Phillies from 1887 to 1938, devolved, in the words of the mother of the author, “from sugar to s**t.”

Opened as the finest ballpark of its day but widely despised during much of its half-century existence, a cash-poor owner vacated it midway through the 1938 season, long after the park had become a testament to institutional neglect. Hopeful Phillies fans flocked to 15th and Huntingdon Streets for three decades before countless Phillies fans stayed home during the ballpark’s 20-year descent into mediocrity.

How could a change of fortune like this have happened?

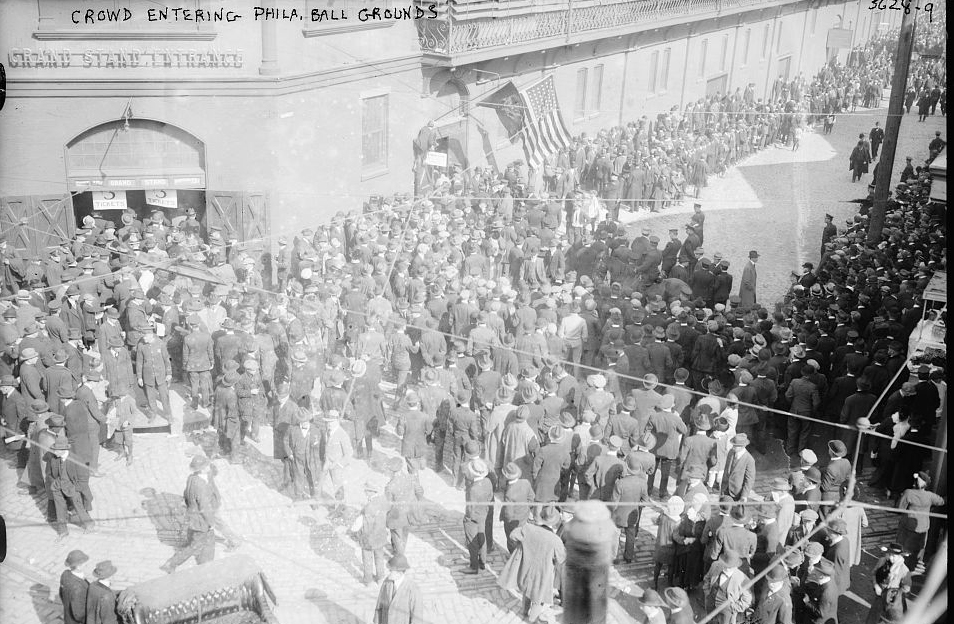

Atlas of the City of Philadelphia, 1910. (G.W. Bromley and Co, Plate 19.)

Phillies owners Alfred Reach and John Rogers built the first version of the park in 1887 and rebuilt another in 1895 after a fire almost razed the original edifice. Both versions were hailed as the finest ballyard of their day.

From their inception in 1883 Recreation Park had been the Phillies home for four seasons. Situated in a residential neighborhood bordered by 24th and 25th Streets between Ridge, Montgomery, and Columbia Avenues, it seated 6,500 fans. But in 1886, the Philadelphia Base Ball Club owners determined the park too small. They then leased, and eventually purchased, a city block bounded by 15th Street, Huntingdon Street, Lehigh Avenue and Broad Street and whose northeast corner contained a stretch of Reading Railroad track. The site was not pretty, having formerly been an old brickyard rippled with branches of Cohocsink Creek and containing a large putrid pond.1

Diligent work by architects Deery and Keerl and builder Joseph Bird transformed the site into a ballpark that featured a two-tiered combination brick and wood grandstand, called a pavilion, with a main entrance through a massive dome-topped structure at 15th and Huntingdon Streets. Corner turrets topped the pavilion overlooking a playing field reclaimed from the brickyard and pond with 120,000 wagonloads of dirt.2 Each turret contained toilet rooms with running water on the three levels. At each end of the ground floor under the pavilion were ticket offices, restaurants, retiring rooms, players’ dressing rooms and lavatories with shower baths.3

Spectators in the pavilion witnessed a playing field less cramped than Recreation Park. The right field foul line, though exceeding Recreation Park’s length of 247 feet, presented a still-tempting target at 290 feet, though it fronted a wall 12 feet high with a 12-foot wire screen. The entire park was enclosed with a brick and wood wall. The park could seat nearly 13,000 customers, more than 5,000 in the pavilion and an additional 7,500 along the foul line bleachers.4

Because Lehigh Avenue did not extend to Broad Street from 15th Street, left field measured 435 feet from home with a 40-foot ascending, sloped terrace five feet high in front of a border fence where overflow patrons could stand. Another boundary fence ran diagonally from left-center field to right-center field through to the right field wall, shielding the railroad tracks and making center field 330 feet from home.5

The stands along the foul lines angled toward the outfield corners which allowed for carriage parking spots underneath and on the grounds behind, enough for 55 carriages. Carriage patrons accessed parking by entrances on Huntingdon Street, Broad Street and 15th Street, respectively. Well situated on a major thoroughfare bounded by residential districts and manufacturing plants with nearby trolley and train lines, the Phillies and the park could draw fans from near and far. Rogers and Reach named the park the Philadelphia Base Ball Grounds.6

Opening Day for the new park on April 30 featured a beyond capacity crush of 18,000 fans and cranks, including 3,000 dignitaries, politicians and Philadelphia society luminaries invited by the Phillies. With every seat taken, park officials allowed fans onto the left field slope. The crowd was so dense that 5,000 others could not get in. Those who could witnessed a lengthy slugfest won by the Phillies against the New York Giants, 15-9, called in the bottom of the seventh due to fading light.7

The next day’s Philadelphia Inquirer trumpeted praise for the new ballfield. “Eighteen thousand people were present to attest their appreciation of the business enterprise which gave to Philadelphia the finest and grandest sporting park in the world.”8

The Phillies fielded competitive teams during the original park’s eight seasons of activity, winning 583 and losing 475 for a .551 percentage.

Although the Philadelphia Times in 1887 heralded the new park in a column heading entitled “Built to Last Forever,” a fire on August 6, 1894, destroyed the pavilion, the right field fence and part of both bleachers. The blaze began as the teams warmed up for a game. Both teams battled the fire, which became an inferno as it spread along the wood grandstands.9 The Phils played 10 games at the University of Pennsylvania’s ballfield in West Philadelphia while makeshift wooden stands were hastily built at the damaged park to last out the season. No cause for the blaze was definitively established.10

Rogers and Reach then decided to build a ballpark worthy of being called a palace. They built this second ballpark of wood, steel, iron and brick, which by itself would have established their reputation as innovators, but they went one step further. They had noted the complaints of their patrons who disliked the obstructed view seats created by supporting posts in two-tiered stadia of the era. They decided to eliminate the posts and pioneered the use of a cantilever design. Reach himself described the principle and the park in a long letter to fans and the community.11

This imperfect photograph [note broken foul line] of a Negro League World Series game in 1924 best illustrates what cantilever design offered fans: a single, multi-trussed steel column well back of the field that holds up the upper deck. Notice the absence of supporting posts for most of the seats in the first and second tiers.

(William Cash/Lloyd Thompson Collection, Courtesy of the African American Museum in Philadelphia)

Reach and Rogers hired architect John D. Allen, along with builder R.C. Ballinger. Together they designed and built the main grandstand using 15 columns cantilevered to support the upper deck for 1,750 spectators. Another 3,750 would sit on the main level, many of them in front of the columns. With the right and left field bleachers, capacity could reach 15,000.12

Wrapped within an ordinary brick wall, the new Philadelphia Baseball Grounds sparkled from day one. Reach had promised a wonderful, fireproof structure. All the seats and aisles in the grandstand and bleachers remained wood, but all the stairways, steps and concourses were cement. Builder Ballinger installed water hose connections throughout the grandstands that ensured any possible fire could be properly combatted. Another wide concourse wended behind the grandstands, allowing room for vendors and fan entrances to the seats. The main entrance at 15th and Huntingdon Streets featured a gigantic, six-sided, three-story structure for fans to come and go.13

On May 2, 1895, the new ballpark opened to rave reviews. Opening Day drew more than anyone expected, with some 20,000 patrons cramming themselves into the structure and grounds. One of the largest crowds to witness a ballgame in Philly to that time gazed upon a grass ballfield with dimensions of 390 feet to left field, center at 408 feet and a right field wall 290 feet from home. The brick wall in right field measured 12 feet tall topped with a 12-foot heavy wire screen. It would be a tempting target today, but not so much during the so-called Deadball Era.14

As in 1887, the Philadelphia Times praised the new park in columns following Opening Day, 1895. “…as [the crowd] gazed around at [the grandstand’s] mammoth proportions they gave expressions to their thoughts in many words of praise.” The Times added: “If those under whose directions this great improvement has been completed could have heard some of the remarks passed, they would doubtless have felt amply repaid for their troubles.” The Public Ledger claimed 21,000 had passed through the turnstiles, then spent two columns listing the names and titles of the 3,000 Philadelphia luminaries, “merchants, clergymen, lawyers, artisans,” invited by Reach and Rogers.15

The Phillies renamed their home grounds National League Park and played decent baseball for 23 seasons at the resurrected ballfield, posting 1,746 wins against 1,638 losses. One of the finest outfield trios in baseball history roamed the outfield grass during the early 1890s: Ed Delahanty, Sam Thompson and Billy Hamilton, all future Hall of Famers. Two other Hall of Famers teamed together in the late 1890s with Delahanty: Elmer Flick and Nap Lajoie. Fans witnessed a lustily hitting team that lacked effective pitching – a phenomenon that would recur throughout Phillies history.

Ultimate success, copping the National League crown, might have been possible in this Phillies era had it not been for Rogers’ personality and The Catastrophe of 1903. Rogers’ prickly demeanor caused ruction with Reach, manager Harry Wright and others in the Phillies pantheon that ultimately led to the sale of the Phillies in February 1903 to a group headed by James Potter. The Phillies played middle-of-the-standings ball from 1903 to 1913, with only one second-place finish.16

The Catastrophe of 1903

In the second game of a doubleheader with the Boston Nationals on August 8, 1903, numerous thrill seekers in the left foul line bleachers crammed onto a flimsy balcony overlooking 15th Street, drawn by the terrified screams of a young girl on the street below. Twelve died and 232 were injured when the balcony collapsed, causing a cascade of bodies plunging down 50 feet onto the cement sidewalk and street.17

Tragedy became travesty when the Phillies refused responsibility for the collapse of their property. Reach and Rogers had retained land ownership in the sale to Potter, but they and the Potter group dodged responsibility. Potter, et. al., did so by declaring bankruptcy. After numerous lawsuits, public inquiries and legal verdicts, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled finally that the fans were responsible for their deaths and injuries. Reason? Because they shouldn’t have crowded into such a precarious space; they should have known better and avoided the spectacle.18

In the years following this tragedy, the team went through a number of owners, as did the ballpark. The unlucky Potter relinquished his presidency in 1904 and his ownership in 1909. In a convoluted process, a group of investors engineered by Pittsburgh Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss, but fronted by Horace Fogel, purchased the team and park in 1910. Charles Phelps Taft of Cincinnati and Chicagoan Charles Murphy, both men of wealth, bankrolled the group and were the true owners. Eventually, the Phillies became owned by another out-of-towner, William Baker, and an assortment of limited partners while the Murphy/Taft tandem retained park ownership, leasing it to Baker’s group in 1913.19

In its early years, the ballyard experienced periodic improvements by Reach and Rogers as well as other owners who made their own upgrades, especially to the rebuilt park. These improvements allowed more team facilities, access, and mobility within the park as well as increased seating. A two-story clubhouse replaced the empty land in deep center after the purchase of the triangle-shaped parcel in the northeast corner when the tracks moved away in 1893. An entrance at Broad and Lehigh with long catwalks above each wall in left and right field allowed fans to enter and find seats. Two lengthy bleacher sections in left and right hung on the walls supported by timber beams. Fans referred to them as the hanging gardens.20 Significant alterations by the Potter ownership included adding bleacher seats on the playing field in left and the rebuilding of the foul line bleacher seats in left following The Catastrophe.21

The wealthy Taft/Murphy tandem brought major improvements. They added decks to the main pavilion all the way to Broad Street and increased the left field decks 100 feet along 15th Street to the foul line bleachers. The left field bleachers were also extended almost to the clubhouse. Additionally, they replaced the bleacher seats atop the clubhouse. These improvements raised capacity to more than 18,000.22

Over time the playing field’s dimensions changed, in part because of owner-inspired alterations or for other reasons. Originally, the left field fence was 435 feet from home plate, but it moved in when Lehigh Avenue went through to Broad Street in 1893 and when Potter added the bleachers, settling on 338 feet or so during the rest of the park’s lifetime. Center field also fluctuated but eventually landed on 408 feet. Right field, so close to home plate, changed lengths when home plate moved twice. Originally 290 feet away, the distance shrank to 272 feet in 1896 after a home plate repositioning but measured 281 feet in 1925 after another move of the plate, remaining that distance until the Phillies’ exit in 1938.23

National League Park also featured a number of additions which became subtractions as time passed. These included bleacher seats on the clubhouse roof, team offices as well as a large entrance at Lehigh Avenue and Broad Street, the catwalks and the hanging garden bleachers. Additionally, a swimming pool constructed inside the center field clubhouse in better days could not be removed because of cost but was drained of its water.

This photograph of an exercise demonstration at the ballpark shows the additions/subtractions. Note the catwalks, the hanging gardens and the clubhouse bleachers. These additions were ordered removed by the Board of Building Inspections following several inspections after The Catastrophe of 1903.

Second grade boys in the flag drill in the Philadelphia Ball Park, Gospel of the Turn Verein, Outing Magazine, 1905:178. (Courtesy of Hathitrust.org)

Lastly, and comically, at one point the frugal Baker had grazing sheep serving as groundskeepers to save costs. The sheep were subtracted when a ram butted Phillies official Billy Shettsline as he walked across the field.24

Unfortunately, most improvements gradually ceased during the park’s long demise after World War I, mainly because Baker operated the team and park on Phillies’ revenue.25

The need for extra revenue led Baker to seek ways beyond National League baseball to raise money from the aging structure. Two notable attempts involved both of the nation’s major sports.

The local Hilldale Daisies of Yeadon/Darby hosted the first two games of the first Negro League World Series at Broad and Huntingdon in 1924 against the Kansas City Monarchs. In the 1925 Series, Hilldale also hosted two games at Baker Bowl, winning both and leading to their Series win against the same Monarchs. The park regularly rented to Black teams.26

Additionally, from 1933 to 1935, the park hosted the nascent Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League. They fared just as well as the hapless Phillies, compiling a 9-21-1 record before moving to Municipal Stadium in South Philadelphia.27

Let us now talk about three of the most noted characteristics in the park’s history: The Hump, The Wall, and the park’s nickname, Baker Bowl.

Some Baker Bowl historical accounts, to this day, refer to a “hump” in center field supposedly caused by a railroad tunnel. Not so. A hump in center field was never a part of the playing field.

The nickname may have derived from the long slope in left field seen on Opening Day 1887, but the Phillies always referred to that slope as the “terrace.” It disappeared after the city forced an extension of Lehigh Avenue through to Broad Street in 1893.

Another derivation could have been the banked turn in center field of the bicycle track built into the park when it opened. Diligent research, however, has shown the term “hump” attached to Baker Bowl is due to the raising of Broad Street, Huntingdon Street and Lehigh Avenue abutting the center and right field wall in 1893.28 The raising eliminated two vexing railroad street-level grade crossings to pedestrians and transport at Lehigh Avenue and Broad Street. The tracks were relocated 90 feet away from the park but depressed 6 feet lower and were now underground. The elevation of Broad and Huntingdon streets created a parabolic-like road level 11 to 12 feet high. Newspaper accounts of the day usually referred to the project as “the hump.” As of 2023, the “hump” was still in view as seen by travelers on Broad.29

The Wall in right field was a hodgepodge of materials and intent meant to prevent the cheapest of home runs. Originally a 12-foot brick wall topped with a 12-foot wire fence 290 feet from home plate, various owners fashioned it into a deterrent against the pop-up home run. Reach and Rogers raised it to 27 feet in 1894 and reconstructed it entirely in 1897 to 32 feet.30 During the so-called Live Ball Era of the 1920s when batters swung away lustily, pop-up home runs over the wall became common. Baker thought those home runs from the new ball were cheap. As a further deterrent, he raised the wall to 40 feet in 1929, raising its height to 55 feet with a 15-foot wire fence added.31

Pitchers hated it because its nearness gave many a batter hits that would have been outs in other parks, directly affecting their earned run averages. The Wall became nearer in 1896 by the repositioning of home plate 13 feet toward center field, measuring 272 feet from the batters’ box.32 Many a jibe was written about its nearness but ex-Philadelphia Record sportswriter and Pulitzer Prize winner Red Smith summed it up best many years after the wall disappeared: “It might be exaggerating to say that the outfield wall cast a shadow across the infield, but if the right fielder had eaten onions at lunch the second baseman knew it.”33

While it was a bane for pitchers, the Wall was a boon for batters, especially for home run hitters. The nearness allowed Phillies batters more opportunities for hits and homers, since they played 77 games a season at Baker Bowl. Rich Westcott, in his Ballparks of Philadelphia, asserts: “Between 1911 and 1938, Phillies players led or tied for the National League in most home runs hit at home 19 times.” He added, “187 Phillies hit 1,314 home runs in nearly 52 years at their odd little hitter’s park at Broad Street and Lehigh.”34

The most memorable visual manifestation of this structure was a wall coated in tin, dented with the impact of the many balls that ricocheted off it and painted with a sign featuring Lifebuoy soap in gigantic letters. It was one of the more famous walls in baseball history because of the park’s longevity, since many a ballpark from the nineteenth century were squeezed into tight urban lots, forcing builders to fit short park dimensions with high walls.

Lastly, sportswriters of the era loved alliterative phrases like Baker Bowl. (Other examples included Babe Ruth, the Sultan of Swat, or the Washington Senators, known in some circles as the Toga Toters.) Baker claimed to have renamed the park after himself, but the official name remained National League Park. The Baker Bowl nickname began surfacing in print only after 1923 and gained in popularity in the following years. This appellation appeared first in a column on July 11, 1923, during an account of a game against the Reds, 10 years after Baker assumed ownership.35

National League Park experienced all the highs and lows available in major league baseball and some beyond. The Delahanty-led teams of the 1890s, the feats of future Hall of Famers Grover Cleveland Alexander and Chuck Klein, and the World Series of 1915 were always offset by the nadir of the Baker-era team performances, the deteriorating infrastructure, the lack of amenities – the ballpark had no parking for cars, no lights, no electronic sound system – and the stingy and frugal ownership administration of Baker. Deferred maintenance made worse by a nationwide depression doomed the one-time palace that Reach and Rogers had built.

Despite this dire state of affairs, National League Park also experienced numerous bright spots, including the hosting of three 1915 World Series games. The Series pitted the Phillies against the two-time Series champion Boston Red Sox. Nearly 60,000 attended the games in Philly, reaping some profit for Baker.

The Phillies’ first World Series featured the first appearance in a Series by a current US President and the first World Series appearance of future Hall of Famer, Babe Ruth. The right-handed Woodrow Wilson threw out the first ball before the start of Game Two, setting a precedent for future Presidents. Ruth, however, grounded out in his only appearance. Ruth had his last at-bat as a player in the same park twenty years later, a groundout in the first inning of a Braves-Phillies game on May 30, 1935. Fans bid him a warm welcome with a pregame floral tribute.36

Disappointingly, the park played a major factor in the decisive Game Five in 1915. Baker had eschewed the use of the more spacious Shibe Park for the Series but still sought to maximize profit by installing center field bleachers for the anticipated large crowds. One of those large crowds witnessed a Phils victory in Game One behind the pitching of Alexander. Unfortunately, another large crowd in Game Five watched ruefully as Boston’s Harry Hooper bounced two home runs into the bleachers, one of them a game-winner in the decisive ninth inning. The game, and the Series, went to the Red Sox. 37

Other events hosted to increase revenue drew thousands to the stadium. These included bicycle contests, rodeos, police and firemen fund-raising parades, circuses, religious crusades and exercise follies. Boxing matches were popular. Perhaps most notable were the first open-air boxing match in Philadelphia history involving “Philadelphia” Jack O’Brien vs Bob Fitzsimmons in 1904 which drew 6,000, and the Primo Carnera-George Godfrey match in 1930, which drew 35,000.38

Unfortunately, two years after that World Series bright spot, the team and park entered what many team stalwarts call the Dark Ages. It began with, arguably, the dumbest decision in Phillies history – the trading of Alexander at the end of the 1917 season. Cheapskate Baker considered the pitcher a liability because of his eligible draft status in World War I. Baker sent him and his batterymate, Bill Killefer, to the Cubs for two players plus $55,000. It remains one of the most lopsided trades in baseball history: Alexander and Killefer sported a combined career WAR of 129.1 while the two Cubs totaled 4.5 in their careers.39

Alexander had led the Phils to a pennant and three second-place finishes. He had won 190 games for the team and was still in his prime at 30 years of age. Curses do not exist, but for the next 21 seasons the team finished above .500 only once, but last or next-to-last sixteen times. Lackluster teams – the Phillies lost more than 700 more games than they won over that time period — and an average per-game attendance of 3,078 in a park that sat 18,000 did not deter Baker Bowl from deteriorating further.40

An example of the park’s creeping deterioration occurred on May 14, 1927, when rotting timbers in the all-wood right field lower grandstand collapsed. A sudden squall had caused many patrons to cluster under the second deck overhang. Several innings later those clustered showed their approval by stamping their feet during a Phils’ rally, which intensified following a home team grand slam. An inning later the stressed timbers underfoot crumpled, creating a jagged funnel into which dozens tumbled. More than 50 spectators were injured, and one person suffered a fatal heart attack. Dozens stampeded onto the field, panicked about further collapses. The head umpire called the game shortly thereafter.41

William Baker died in 1930. Baker’s will split his Phillies shares between his wife, Mary, and his secretary, Mae Fallon Nugent. Mary had no intention of running the team and allowed Phillies business manager Gerald Nugent, Mae’s husband, to take the helm. Nugent was clever and resourceful, moving and trading good players for cash and emerging talent during his 9-year tenure. His acumen kept the Phillies up and running during the Depression. However, he had no personal wealth. The money that he acquired in trades, concessions and attendance went to the owners, staff and team, but little was spent for upkeep of the ballpark and almost nothing was invested to gain more wealth. Already worn out, the park’s structures and amenities steadily deteriorated during the 1930s.42

So, why did the Phillies stay put in such a wreck? They owned the park but did not own the land the park occupied; they leased it from, ultimately, the Murphy family of Chicago. They were responsible for upkeep of the park. The lease on the land — agreed to by the owner group in 1910 led by Fogel, but actually owned by Taft and Murphy — bound subsequent owners William H. Locke and Baker to the lease’s terms. It contained expensive buyout clauses that neither they nor the team’s future owners could afford upon violation of the lease. In part, lease terms included escalating rents, taxes, water rents and fire insurance. According to Westcott: “In 1930 they were paying $25,000 per year in rent, plus $15,000 in taxes and $5,000 for grounds upkeep.” The lease obligated any owner of the team to pay up for 99 years unless re-negotiation occurred.43

Talks to move from Baker Bowl to Shibe Park with Athletics owners Ben Shibe and Connie Mack were off and on during Baker’s and Nugent’s ownership. They never solidified, usually foundering on lease terms and the sharing of concessions revenue.44

And so it went, year after year of wear and tear; season after season of losing teams and day after day of sparse crowds, all of it accompanied by a crippling lease. The public responded by doing other things while sportswriters, national and local, wrote with rising derision of Baker Bowl. Ed Burns, writing in the Chicago Tribune in 1937, opined: “What a ballpark. There must be 18 better ones in the American Association, Pacific Coast League and the International League.” He added: “The [wood] double deck shivers quite a bit on the occasion when a capacity crowd is being entertained. The whole structure is covered by a sheet metal roof. And what a jolly shower of rust whenever a foul ball plunks down on said roof.”45

Locally, Red Smith lamented the park, calling it “a fusty, cobwebby, House of Horrors” in a place where “…nothing was alive except the ivy on the clubhouse walls.”46

That House of Horrors memory must have stayed with Smith, because 38 years later he wrote: “Baker Bowl in Philadelphia was a stately pleasure dome when Al Reach built it for his Phillies in 1887 but by the 1930’s and ‘40’s [sic] it bore a striking resemblance to a rundown men’s room.”47

The Phils were in familiar territory early in the 1938 season: last in the National League with a 1-10 record at the end of April. Talks between Nugent and Mack for a move to nearby Shibe Park reopened in spring training, as did other talks with the lawyers of Chicago’s Murphy family estate, owners of the lease on worn-out Baker Bowl.48

On Friday, June 25, Gerry Nugent announced that plans to move to Shibe Park were being finalized. And on Monday, June 27, it became real. The Phils were to leave Baker Bowl. Their first game at Shibe Park would be a holiday doubleheader on July 4, 1938.49

The Phillies’ last game at Baker Bowl lacked any kind of ceremonial flair like the first game had displayed when an overflow crowd of cranks, celebrities, society ladies and politicians thronged the field and stands. Fifteen thousand people had come out in 1887, but on June 30, 1938, an estimated crowd of 1,500 showed for the Giants-Phillies game. Bill Dooly of the Philadelphia Record wrote: “Baker Bowl passed out of existence as the home of the Phillies yesterday afternoon. Equal to the occasion, the Phillies almost passed out with it by providing one of their inimitable travesties, a delineation in which they drolly absorbed a 14 to 1 pasting.” His column ended, “Thus, more or less, did the Phils bid goodbye to Baker Bowl.”50

The next day the Phillies trucked everything up the street to Shibe Park at 21st and Lehigh Streets, leaving the old yard to its fate. Unfortunately, the relocation did nothing for the Phils’ fortunes. They finished last in the National League at 45-105, losing 18 of their last 20 games and posting a 15-32 record at their new home.

From 1938 to 1950, when it was demolished, the site of Baker Bowl underwent alterations that transformed it into different venues. The first of these was the dismantling of the upper decks to create a racetrack for midget cars in 1939. A fire 29 days after it opened and no lights for night races doomed it. A year-round ice-skating rink and a musical bar, among others, came and went because of calamities and poor attendance. Fires and vandalism visited the site in its later years until a storm collapsed much of the old brick wall, causing its final erasure from Philadelphia’s entertainment scene.51

Currently occupying the site are two eateries, a gas station, a car wash, an electronic parts supplier and the Broad Street Garage of the Philadelphia School District. The only vestige that there used to be a ballpark there is an historical marker erected by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in 2000. It is nice to know that the Phillies appreciated their own history when they hosted the marker for a year at Veterans Stadium, then helped relocate it to the old ballyard’s neighborhood on Broad Street near Huntingdon.52

Finally, so many negatives have been written about National League Park/Baker Bowl, but it must be recognized for one positive legacy to baseball. Baker Bowl is recognized as the first modern ballpark, according to author Michael Gershman, and its pioneering cantilever design set the tone for all modern ballparks, all of which use the cantilever architectural concept to this day.53 For that reason alone, a little bit of much-maligned Baker Bowl lives on in today’s fancier professional ball parks.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Kurt Blumenau and Tom Reinsfelder and fact-checked by Russ Walsh.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for general player, team, and season data.

Camden [New Jersey] Post-Telegram

New York Times

Philadelphia Evening Bulletin

Philadelphia Inquirer

Philadelphia Press

Philadelphia Public Ledger

Philadelphia Record

Philadelphia Times

The Sporting Life

Baumgartner, Stan and Frederick Liebe. The Philadelphia Phillies. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953).

Casway, Jerrold. Ed Delahanty: in the Emerald Age of Baseball. (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004).

Gershman, Michael. Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark. (Boston, New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 1993).

Honig, Donald. The Philadelphia Phillies: An Illustrated History. (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1992).

Kearney, Seamus and Dick Rosen. The Philadelphia Phillies, Images of Baseball. (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2012).

Jordan, David M. Closing ‘Em Down: Final Games at Thirteen Classic Ball Parks. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2010).

Jordan, David M. Occasional Glory. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2002).

Ritter, Lawrence S. Lost Ballparks: A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields. (New York: Penguin Books, 1992).

Westcott, Rich. Philadelphia’s Old Ball Parks. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Periodicals

Davids, L. Robert. “Baker Bowl,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1982.

Doyle, Edward F. “Baker Bowl,” The National Pastime #15, SABR, 1995.

Morton, Ed, “Baker Bowl,” SABR Ballparks Committee Newsletter, June 2020.

Warrington, Robert D. “Baseball’s Deadliest Disaster: ‘Black Saturday’ in Philadelphia.” Elysian Fields Tri-Quarterly, Volume 25, Number 1, 2008.

Internet

americanfootball.fandom

nbcsports.com

sabr.org

sportstalkphilly.com

thisgreatgame.com

Notes

1 “Fragments of News,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 30, 1886: 3.

2 Rich Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks: 28.

3 “Home, Sweet, Home,” Philadelphia Times, May 1, 1887: 1.

4 “The New Philadelphia Base Ball Grounds,” Philadelphia Press, March 6,1887: 1.

5 “The Grounds Described,” Philadelphia Times, May 1, 1887: 1.

6 “The Grounds Described.”

7 “The Grounds Described.”

8 “The Ballfield,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 1,1887: 3.

9 “Ballpark in Ashes,” Philadelphia Times, August 7, 1894: 1.

10 “To Be Ready on Saturday,” Philadelphia Times, August 16, 1894: 2.

11 L. Robert Davids, “Baker Bowl,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1982.

12 “Surprizes Coming on the Ballfield,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1895: 20.

13 Davids, “Baker Bowl.”

14 “The Phillies Beaten Again,” Philadelphia Times, May 3, 1895: 8.

15 Philadelphia Times, May 3, 1895: 8; “Baseball,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, May 3, 1895: 1.

16 “Reach and Rogers Out of Baseball,” Sporting Life, March 7, 1903: 4.

17 Robert Warrington, “Baseball’s Deadliest Disaster: ‘Black Saturday’ in Philadelphia,” Elysian Fields Tri-Quarterly, Volume 25, Number 1, 2008: 41.

18 Warrington.

19 Rich Westcott, “Philadelphia Phillies Team Ownership History,” Team Ownership History Project. SABR.org. Accessed April 2023.

20 “Baseball Season Here,” Philadelphia Record, March 15,1896, 13

21 “Seating Capacity at Phillies Increased,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 5, 1906: 10.

22 “Grounds Near Ready,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 29, 1910: 10.

23 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, March 14, 1896: 3; “Phils Move Plate to Get More Room,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, February 5, 1925: 13.

24 Westscott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks: 47.

25 Westcott, “Philadelphia Phillies Team Ownership History.”

26 “Hilldale Defeats K. C. Foes,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1925: 27.

27 Edward F. “Dutch” Doyle, “Baker Bowl,” The National Pastime #19, 1995: 27.

28 “Comment About Various Sports,” Philadelphia Inquirer March 18, 1894: 24.

29 “Railway Industries,” Railway World, August 5, 1893: 725; “Railway Industries,” Railway World, October 14, 1893: 967.

30 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, March 14, 1896: 3.

31 “Inside Stuff by James Isaminger,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 5, 1929; 18.

32 “Local Jottings,” March 14, 1896, p. 3

33 “Chuck Klein of Baker Bowl,” New York Times, August 6, 1980: 29.

34 Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks: 38-39.

35 “Red Uprising Beats Phillies in Ten Innings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 11, 1923: 20.

36 “Flowers for Babe,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 30, 1935: 11.

37 David Jordan, Occasional Glory: 53.

38 Doyle, “Baker Bowl;” “Godfrey Loses to Carnera on Foul in Fifth,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 24, 1930: 1.

39 “Phillies Startle the Baseball World by Selling Alexander and Killefer to the Cubs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 12, 1917: 1.

40 Baseball-Reference.com.

41 Jordan, Occasional Glory: 66.

42 Seamus Kearney and Dick Rosen, The Philadelphia Phillies: 69.

43 Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks, p. 94; “Reach and Rogers Out of Baseball,” Sporting Life, March 7, 1903: 4; “Durham Buys the Phillies,” Camden (New Jersey) Post-Telegram, February 24, 1909: 3; “Locke Finally Secures Phila. Baseball Blub [sic],” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 16, 1913: 1.

44 David Jordan, Closing ‘em Down: Final Games at Thirteen Classic Ball Parks: 12.

45 Burns, Ed. Chicago Tribune, Summer, 1937

46 Philadelphia Record, June 25. 1938, 1

47 “A Flag for Betsy Ross,” New York Times, July 2, 1976: 38.

48 “Night Baseball Here in ’39 Hinges on Phillies’ Moving,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 26, 1938: 5.

49 “Night Baseball Here in ’39 Hinges on Phillies’ Moving.”

50 “Phillies Lose Final Game in Baker Bowl,” Bill Dooly, Philadelphia Record, July 1, 1938: 21.

51 Westcott, Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks: 97-98.

52 Bob Warrington, “Baker Bowl Honored with Historical Marker at Dedication Ceremony!,” Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. Accessed April 2023. You can read the marker at: https://share.phmc.pa.gov/markers/

53 Michael Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark: 57