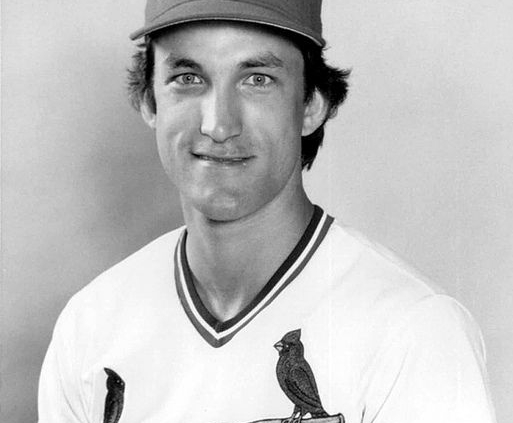

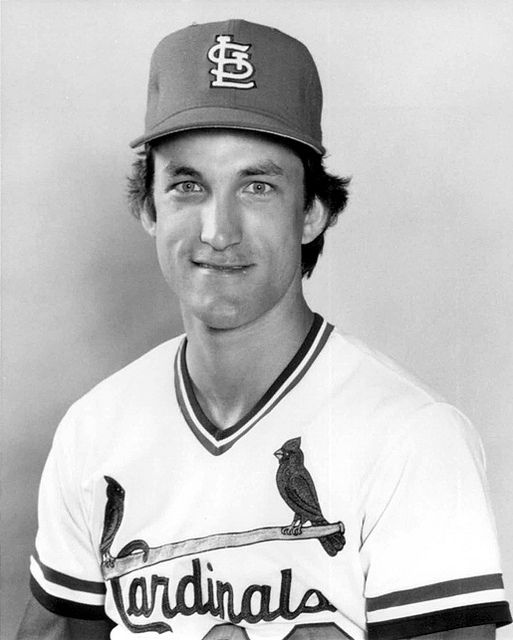

Bill Lyons

Throughout nine years of professional baseball, Bill Lyons established his reputation as a versatile utilityman, capable of playing in the infield and outfield. He played in 88 games in parts of two seasons (1983-1984) with the St. Louis Cardinals, serving as the 26th man on a 25-man big-league roster and an insurance policy against injury. A longtime jack-of-all-trades for the Cardinals’ top minor-league affiliate, Lyons concluded his career by playing all nine positions in his final game. “I think it might be the ultimate compliment to a utility player,” said Lyons.1

Throughout nine years of professional baseball, Bill Lyons established his reputation as a versatile utilityman, capable of playing in the infield and outfield. He played in 88 games in parts of two seasons (1983-1984) with the St. Louis Cardinals, serving as the 26th man on a 25-man big-league roster and an insurance policy against injury. A longtime jack-of-all-trades for the Cardinals’ top minor-league affiliate, Lyons concluded his career by playing all nine positions in his final game. “I think it might be the ultimate compliment to a utility player,” said Lyons.1

William Allen Lyons was born on April 26, 1958, in Alton, Illinois. Then a fast-growing industrial city of about 40,000 residents, Alton is situated on the Mississippi River, 20 miles north of St. Louis. “I grew up a St. Louis Cardinals fan,” Lyons told the author. “I attended my first big-league game at Sportsman’s Park, then called Busch Stadium, in 1964. Who knew I would play for them one day.”2

Bill’s parents were Illinois-born Robert E. and Stella (née Ursch) Lyons. His family owned and operated Lyons Glass Company, which they had founded in 1929. They had three boys, Bob and Bill, who were “Irish twins,” and Dick, four years younger.

An athletic youngster, Bill began playing baseball at around age eight. “My father taught me and my brothers about baseball,” Lyons explained. “He was stationed in Korea and Japan in the 1950s and played for a base team. We grew up paying Wiffle ball in the back yard.”

Lyons dabbled in football but concentrated on baseball and basketball by junior high. He played both sports at Alton High School. Tall, thin, and right-handed, Lyons was always among the most athletic players on his teams. He was a quick guard on the hardwood and shortstop on the diamond, though he also played second and third base, foreshadowing his eventual professional career, and occasionally pitched for coach Wayne Tyler’s Redbirds.

Lyons harbored no expectations of being drafted out of high school upon graduation in 1976 but wanted to continue his playing baseball. He was recruited by coach Richard “Itchy” Jones, then in the beginning of his legendary college coaching career, and subsequently enrolled at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale on a partial baseball scholarship. SIU had a nationally prominent baseball program and had been to the College World Series four times in a seven-year period (1968-1974). “I knew SIU would be a great program to be a part of and it turned out that way. I fell in love with the campus the first time I visited. It was far enough away from home (about 2½ hours) to feel like I was away, yet close enough for my parents to see me play. Jones was a fantastic coach and mentor, too.”

Initially recruited as a shortstop, Lyons was moved to second base and earned a reputation as a valuable, versatile infielder. In his first season, the Salukis won the Missouri Valley Conference title and advanced to the College World Series. “It wasn’t nearly as big a deal then as it is now with all the hype and media coverage,” said Lyons about the tournament that took place in Omaha, Nebraska. “Just having a chance to be on one of the best teams in the country was an experience.” The Salukis finished in third place behind traditional powerhouse Arizona State and South Carolina.

Like many of his teammates (which included future Toronto Blue Jays star Dave Stieb), Lyons played in a college summer league. With help from Jones, Lyons joined the Bloomington Bobcats in the Central Illinois Collegiate League after his freshman year and played two additional years in the CICL’s two-month-long season.

At the conclusion of his senior year at SIU, in 1980, Lyons received the team’s annual Abe Martin Award, presented to a baseball player who “exhibits honesty, leadership and character.”3 Big-league scouts were common sights at SIU and in the CICL, but Lyons did not recall ever speaking to one. He participated in a Cincinnati Reds tryout camp in St. Charles, Missouri after graduating in May, but was unsure about what to expect in the June amateur draft. Lyons admitted he was “disappointed” that no big-league team called him. “I thought my baseball career was probably over after the draft,” said Lyons. “I was just playing ball in a local weekend beer league.”

Just when Lyons was prepared to send out resumes and begin looking for a job, he had some good news in late July. “I came home one day after fishing with my father and there was a message from the Milwaukee Brewers,” he explained. “They wanted to sign me. The next day I was on a flight to Calgary to meet the club.” Signing as an undrafted free agent, Lyons didn’t receive a bonus, “just the opportunity to play.” Four decades later, Lyons was still unsure how the Brewers found out about him and had no contact with the club before that fateful message. According to the SABR Scouts Committee, Ray Poitevint, a longtime scout who had followed Harry Dalton’s move as Baltimore Orioles GM to the same position with the Brewers, was given credit for the signing.4 Lyons was assigned to the Butte (Montana) Copper Kings of the rookie-level Pioneer League.

Lyons’ performance in six weeks at Butte (.315 batting average and .489 slugging percentage in 116 plate appearances) earned him an invitation to the Brewers spring training camp in Arizona as a non-roster invitee in 1981. “I was told at the end of camp that the club liked me,” explained Lyons, adding that he anticipated being promoted to Class A. “But they were looking to send me back to rookie ball. I thought I’d be old for another year of that. Several days later I was released.”

Lyons was shocked at the unexpected turn of events in his career and was confronted by a stark dose of reality. “My release [in early April] gave me an indication that professional baseball involved a lot of politics,” he said. “If a team has money invested in a player, they are going to give him a look and then more over a player they have nothing invested in.”

Back home in Alton, Lyons once again was at a crossroads. “As it turned out, my release from the Brewers was the best thing that could have happened to me.” A few weeks later, the Cardinals called looking for a shortstop and invited him to their extended spring training in St. Petersburg. Three and a half weeks after his release from the Brewers, Lyons signed as a free agent on April 29 with the Cardinals.

Assigned to Erie in the Class A short-season Pioneer League, Lyons emerged as a genuine prospect. He split his time at third and second base (also appearing occasionally at shortstop), earning an all-star berth. Even more promising was the pop in his bat: he led the circuit with 65 RBIs while batting .327.

Lyons began the 1982 season with the Springfield (Illinois) Cardinals in the Single-A Midwest League and began his quick ascent up the organizational ladder. After batting .332 and slugging .507 in 55 games, he jumped to Triple-A Louisville, in its first season as the Cardinals’ affiliate in the American Association. “I assumed I’d be in Springfield the entire year and then be in Double-A in 1983,” said Lyons. “It was a shock to be promoted to Triple-A.” He recalled having to adjust mentally to a new situation and increased pressures. “One day I am playing in the Midwest League in front of maybe 1,000 people, then I am in Triple-A in front of 10,000. You’re just one step away from the majors and playing against guys who had big league experience.”

Despite the promotion, Lyons had a difficult time finding playing time. Skipper Joe Frazier had a versatile utilityman Rafael Santana, who played the same three positions as Lyons, and a hot shortstop prospect in Kelly Paris (who batted .328). After 24 error-free games at third base, Lyons was dropped to Double-A for the final month of the season for a chance to play regularly. A .304 batting average and stellar glove work with the Arkansas Travelers suggested that he was ready for another shot with Louisville.

“I was always known more for my fielding,” said Lyons humbly. “Back then, value was placed on fielding. If a shortstop or second baseman could hit, that was a bonus. Expectations have changed in baseball.”

As expected, Lyons began the 1983 season with Louisville, where he encountered his most influential manager. “If not for Jim Fregosi, I would not have made it to the big leagues,” said Lyons unequivocally about the former All-Star infielder and big-league manager who was in his first year in the Cardinals organization. “Fregosi didn’t know me from Adam when we went to spring training, but he must have seen something he liked,” said Lyons. “He instilled confidence in me and helped me get everything out of me I could. He made me feel appreciated as a player.”

Lyons played primarily at third base, though he moved around the infield, even playing first base for the first time. He also got his initial trial as an outfielder. Batting a sturdy .271 with 60 runs scored in 77 games, he got some unexpected news after a home game against the Indianapolis Indians. “Fregosi came over and says, ‘Great game. Go get them in St. Louis,’” recalled Lyons. “I looked at him and said, ‘What did you say?’ That was the first I had heard about my call-up.”

Lyons reported to the Cardinals on July 19 to replace utilityman Dane Iorg, who’d landed on the 15-day disabled list. Expecting a short stint with the reigning World Series champions, Lyons stayed in the big leagues for the rest of season.

Lyons seemed ideally suited for “Whitey Ball,” the style of play named after Cardinal skipper Whitey Herzog which stressed speed and defense. Standing 6-foot-1 and weighing 175 pounds, Lyons was a cerebral player who made up for a lack of physical power with gritty determination. The scrappy infielder was a capable slap hitter who regularly made contact. and drew more walks than strikeouts in his career. He was also an aggressive baserunner, coming off 21 stolen bases in 24 attempts in Louisville.

After their first pennant and championship since the halcyon days of Bob Gibson and Lou Brock in the 1960s, the Cardinals were scuffling and struggling to play .500 ball. Nonetheless, they had a strong infield, anchored by eventual Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith at short, future All-Star Tom Herr at second, and Ken Oberkfell at third. Lyons knew his playing time would be limited. His first game in uniform, on July 19, was coincidentally Alton-Godfrey Night at Busch Stadium, but he did not play.

Lyons debuted the following evening against the San Diego Padres and was just inches from being a hero. With the Cardinals trailing, 5-3, Ozzie singled to start the ninth. Herzog sent in Steve Braun to pinch-hit against Luis DeLeon, but when left-handed reliever Sid Monge took the mound, Herzog quickly changed his mind. “I was sitting on the bench and heard Whitey Herzog call my name to pinch hit,” remembered Lyons. “At the plate I kept thinking ‘please don’t swing at three in the dirt.’ Monge threw one down the middle and I hit it square. It came close to going out and landed on the warning track.” It was caught.

The Cardinals were a tight-knit squad. Lyons admitted that it could have been “intimidating” joining a team fresh off a World Series title; however, he explained that his teammates made him feel welcome and part of the team. “Oberkfell came up to me on the first day and gave me a couple pairs of turf shoes,” said Lyons. “All I had was my red spikes.” He also thought that his attitude probably helped him transition to the big leagues and gain the respect and trust of his teammates. “I knew my place, wasn’t popping off, or cocky,” revealed Lyons. “I kept my mouth shut, ears open, and played hard.”

In his first two weeks with the Cardinals, Lyons played at shortstop, second base, and third base, pinch-hit, and pinch-ran. “My versatility gave me an opportunity to play in the major leagues,” said Lyons.

Asked about his approach of being a utility player expecting to serve as a late-inning defensive replacement, and be ready to play three positions and in diverse roles on a moment’s notice, Lyons had a deliberate response. “I was accustomed to moving around and playing different positions from college and the minors,” he said. “It’s a matter of physical and mental preparation. Before every game I took ground balls at all three positions to be prepared to play.” He admitted that he might not have had the physical tools of his teammates, but compensated for that with a hustling, competitive approach. “I had a decent arm, but not as strong as many other guys.”

Lyons picked up his first big-league hit in his first start, at second base, against the Los Angeles Dodgers at Busch Stadium on July 24. “I remember it well,” said Lyons excitedly. “It was a fastball from Jerry Reuss and I lined it into center field for a single.” Hits were otherwise few and far between for Lyons, who collected 10 all season (.167 batting average) in limited action. He competed for playing time with another versatile utilityman, Mike Ramsey; meanwhile, Smith and Oberkfell were both healthy, playing in excess of 150 games. Lyons made 33 appearances in the field, including 12 starts at second base, most of which were in September when Herr was injured. The Cardinals offense was a tick better in 1983 than in the previous year, but their pitching plummeted (ranking 10th of 12 NL teams with a 3.79 ERA), leading to a disappointing fourth-place finish (79-83) in the NL East.

Growing up a half-hour from St. Louis, Lyons was well accustomed to the city’s sweltering heat and oppressive humidity. “It was amazingly hot on days games at Busch Stadium in the summer,” he said. The all-purpose stadium was known for some of the most brutal playing conditions in the country — temperatures were routinely in the 90s, which heated the artificial surface to 110 and even 120 degrees. “We had sunken dugouts, but you could sit on the steps and watch the game,” explained Lyons. “I remember seeing the heat waves and the distortion coming off the field. We also had buckets of ammonia water and towels in the dugouts to cool off.”

Reporting to Cardinals spring training in St. Petersburg in 1984, Lyons was immediately struck by its difference from the minor-league camps he had experienced. “In minor-league spring training we had hundreds of guys in camp,” he said. “They are trying to put together seven or eight teams from rookie ball to Triple-A. You can really get lost in the shuffle. At the big-league spring training, at Al Lang Field in St. Pete, we had just over 40 guys. You got stars, veterans, and high draft picks.” Lyons remembered the camaraderie among the players and mentioned the opportunity to play against American League teams in the Grapefruit League as an exciting chance to compete against players and teams he didn’t know. “Back before interleague play,” said Lyons, “taking the field against AL teams was special.”

Lyons recalled that one of the fixtures at spring training was longtime coach and instructor George Kissell, a Cardinals lifer who eventually spent seven decades with the club until his death in 2008. “Kissell knew everyone in the organization and introduced us to the Cardinal Way,” said Lyons. “Whenever he came to the clubhouse, he started jabbering. He had nicknames for everyone and called me Wild Bill. He was always teaching and had a fungo bat in his hand. He picked your brain, emphasizing thinking and anticipating what would happen in a game.”

“It was a tough year,” said Lyons about 1984 which started off promising. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Lyons had a productive spring training and beat out two other utilitymen for the last spot on the club’s 25-man roster. One was veteran Vic Harris, attempting to make it back to the majors after playing the previous three seasons in Japan; the other was Floyd Rayford.5 Redbirds beat writer Mike Smith reported that Lyons was an insurance policy for Herr, who’d had offseason surgery on his leg.6 Herr proved to be in good health, limiting Lyons to three at-bats in the first three weeks. The 26-year-old was consequently optioned to Louisville to make room for starting pitcher John Stuper returning from the DL.

Lyons was called up two more times, sticking after the latter in late July. He was “ticked off” about being demoted during the regular season, but that initial anger gave way to an evolving series of emotions. “I hoped that I would even get a chance to play [in Louisville] and earn my way back up again,” he explained, noting that there were no guarantees. “I was disappointed about the demotion, and thought that if I stink in Louisville, I might not get another chance.”

The Cardinals’ infield featured two new talents in 1984. Gifted yet troubled David Green, previously tabbed as “the next Roberto Clemente,” moved from the outfield to first base to enable George Hendrick to return to the outfield (Hendrick had replaced perennial Gold Glove winner Keith Hernandez, who’d been traded to the Mets during the 1983 season).7 The hitting and fielding of rookie third sacker Terry Pendleton enabled the Cardinals to trade Oberkfell in mid-July. Those two corner infielders, plus switch-hitting Herr and Smith, meant Lyons had little chance to play.

“I got off to a really terrible start at the plate,” said Lyons, who managed just one hit in his first 24 at-bats through September 1. “You can’t dig yourself into that kind of hole and get out, but I stuck with it.” It was another disappointing season for the Cardinals, who once again struggled to play .500. St. Louis sportswriter Kevin Horrigen wrote “the team is full of frustrated players enduring a frustrating season” and added that “the most frustrated is Bill Lyons.”8 When Herr went down with an injury in on September 15, Lyons stepped in and proved his mettle. He started at second base in the last 14 games of the season; in the final 12 games he batted .333 (12-for-36). He collected at least two hits on three occasions in that stretch, including a career-best three against the Expos in Montreal, lifting his average to .219 at season’s end for the third-place Cardinals (84-78). Opined beat reporter Rick Hummel, “[Lyons] seemed more confident this year when he played the last two weeks.”9

“The game was different when I played,” reminisced Lyons, admitting that he might sound like a “crotchety old man.” Reflecting the tenets of Whitey Ball, Lyons explained, “Strikeouts were bad and we tried to make contact. I tried (Lyons’ emphasis) to hit the ball on the ground (and not in the air). It was all about situational batting. Don’t strike out with a man on third, move runners over, don’t pull a ball with a man on second and no outs.” Lyons opined that current trends in baseball and the lack of balls in play have made the sport “difficult to watch.”

Lyons’ strong ending to 1984 boosted his confidence entering the offseason. “I showed them I could play,” he said. “I knew I’d never be a regular on the Cardinals, but it felt good to play.”

Lyons’ excitement contrasted sharply with what came next. For the first and only time in his professional career, he played winter ball, joining the Indios de Mayagüez in the Puerto Rican Winter League for the 1984-85 season. Manager Nick Leyva’s talented squad, featuring Bobby Bonilla, Sid Bream, and Vince Coleman, went 38-22. During the campaign, the Cardinals informed Lyons that he was dropped from the 40-man roster. “I couldn’t understand why,” admitted Lyons. “The only explanation I got was that the Cardinals needed roster spots in their negotiations with [free agent] Bruce Sutter in order to keep him around.”

While with the Indios, Lyons injured his right hand and played in 37 games, batting .229 in 105 at-bats.10 Lyons was told to report as a non-roster invitee with pitchers and catchers to Cardinals spring training in 1985. The club wanted him to learn to catch, a position that he had never played in professional baseball. “The Cardinals carried only two catchers,” said Lyons. “I was supposed to be the back-up to the back-up.” But it didn’t work out that way. Veteran former All-Star Darrell Porter and three young prospects, Tom Nieto, Mike Lavalliere, and Randy Hunt, were all ready for action.

“I only had a handful of at-bats at camp and didn’t get to play much,” said Lyons. “I don’t think I got a fair shake. That was the last sniff I had of the big leagues.”

Lyons was assigned to Louisville, where he spent the next four seasons (1985-1988). Despite a “cracked thumb,” Lyons played in 134 of the team’s 142 games in 1985, splitting his time at three infield positions and in the outfield (where he’d played just five games previously, all in 1983). Yet he batted just .206 as the Redbirds won the American Association title.11

By contrast, Lyons was off to a hot start in 1986 when fate intervened in July. “I was hitting and playing well and thought I might get another shot,” said Lyons. “Then I broke my hand diving for a ball in the outfield and was out seven weeks. That was the first time I was on the DL. It was bad timing.” Diagnosed with a broken left thumb, Lyons struggled upon his return and finished the season with a .250 batting average.12

Affectionately called Mr. Redbird by local sportswriters and fans, Lyons was a popular player while suiting up for the club in its first seven seasons in Louisville. Upon retirement, he held team records in numerous offensive categories, including games (544), at-bats (1,724), runs (280), stolen bases (105), and extra-base hits (105). He was tied with Gene Roof for most hits (441).

His final game encapsulated his career as an ultimate utilityman. In a rousing tribute at Cardinals Stadium in the final game of the season, on September 1, Lyons became the first Louisville player since Jim Pyburn in 1958 to play all nine positions in the same game.13 “Ending it like this was really nice,” said Lyons, who began the game on the mound and ended it donning the tools of ignorance. “It was a lot more fun than going out and playing one position. I’m glad they let me do it.”14

Reduced to a part-time player in his final two seasons and four years removed from the big leagues, the 30-year-old Lyons hung up his spikes. “I thought it’s time to get on with real life,” he quipped. Lyons revealed that it was an easy decision to step away from the game he loved. The money in the minors “wasn’t great.” Plus, he had married Martha Leach in 1983. They had two children, Andy and Tim, and later a daughter, Emily.

“It took a while to find something,” admitted Lyons about the transition to his post-baseball career. “I needed a steady job with a steady income for my family.” Eventually he landed a job as a claims adjuster with State Farm Insurance and advanced to claims representative at the company’s corporate office in Heyworth, near Bloomington, Illinois. After 29½ years with State Farm, Lyons retired in 2020. As of 2021 he lived in Bloomington with his wife.

“I’m one of the fortunate guys who got to play major league baseball and was blessed with good health,” said Lyons in a moment of reflection. “So many people helped me in my career. You do what you can with the ability you were given.”

Last revised: January 13, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Proia and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Bill Lamb.

Special thanks to Bill Lyons, whom the author interviewed on November 16, 2020, and for subsequent correspondence and discussions to ensure accuracy of the biography.

Gratitude is also extended to Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouting Committee and Jorge Colón Delgado of the SABR Latin America Committee.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 All quotations are from the author’s interview with Bill Lyons on November 16, 2020.

2 Lyons interview, November 16, 2020.

3 “Lyons Wins ‘Abe’ Martin Award,” Southern Illinoian (Carbondale), May 12, 1980: 13.

4 Information via SABR Scouting Committee and director Rod Nelson. Poitevint was a trailblazing scout, and best known for signing Hall of Famer Eddie Murray, Dennis Martinez, Doug DeCinces, Teddy Higuera, and Bengie Molina.

5 Rick Humell, “Redbird Bolster Bench With Howe,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 2, 1984: 5B.

6 Mike Smith, “Lyon Is ‘Odd Man Out’,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 21, 1984: B1.

7 Rory Costello, “David Green,” SABR BioProject. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/david-green/

8 Kevin Horrigen, “Cards’ Lyons (.042) Is Catch-22 Victim,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 18, 1984: E1.

9 Rick Hummel, “Four Go To Head of Cards’ Class,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 2, 1984: D2.

10 Statistics provided by Jorge Colón Delgado, acclaimed historian of the Puerto Rican Winter League, and member of the SABR committee on Latin America.

11 George Rorrer, “As Time Goes On, Lyons Endures as ‘Mr. Redbird,” (Louisville, Kentucky) Courier-Journal, May 15, 1988: C3.

12 George Rorror, “[Joe] Magrane Outduels [Alan] Hargesheimer; Birds Get Rare Win,” Courier-Journal, July 23, 1986: C2.

13 “Lyons to be everywhere in Redbirds’ final game,” Courier-Journal, September 1, 1988: E1.

Full Name

William Allen Lyons

Born

April 26, 1958 at Alton, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.