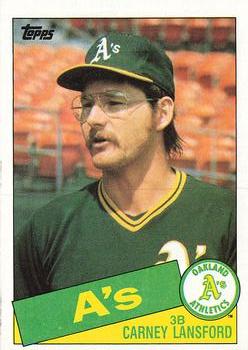

Carney Lansford

When baseball fans reflect on the great Oakland Athletics teams from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, there is a lot to recall. Three straight pennants (1988-1990) and one world championship (1989) is a good start.

When baseball fans reflect on the great Oakland Athletics teams from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, there is a lot to recall. Three straight pennants (1988-1990) and one world championship (1989) is a good start.

Teams do not put together those types of seasons without a solid core of players. A starting rotation led by Dave Stewart, Bob Welch, Mike Moore, and Storm Davis. A closer converted from starting who won the American League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards in the same season (1992), Dennis Eckersley. Maybe what comes to mind are the tremendous clouts of the “Bash Brothers,” Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco. Still others might enjoy the memory of Rickey Henderson stealing yet another base on his way to becoming the all-time stolen base king in 1991.

One of the constants on those powerful Oakland clubs was third baseman Carney Lansford. In 10 years with the A’s (1983–1992) Lansford batted .288. In the field, Lansford led AL third baseman in fielding for three seasons (1987, 1988, 1990). Every successful baseball team has them: the quiet, steady professional who goes about his job with little flash and is not noticed until he is no longer there.

Lansford retired after the 1992 season. He went into coaching, passing his intimate knowledge of hitting opposing pitchers on to younger players. That description is Carney Lansford in a nutshell: Competitive, professional, knowledgeable.

Carney Ray Lansford was born on February 7, 1957 in San Jose, California. He was the second of five sons – Ernie, Gary, Phil, and Joe – born to Mr. and Mrs. Tony Lansford.1 Joe Lansford also played in the major leagues, appearing in 25 games with San Diego (1982-1983). and Phil was a number one pick of Cleveland in 1978 but he never made it past the Class A level in the minor leagues. Tony Lansford worked for 32 years at the Libby Cannery.

Lansford participated in all sports when he was a youngster, but baseball was his strong suit. Carney’s team made it to the Little League World Series at Williamsport, Pa., in 1969. The Santa Clara team, which represented the West Region of the United States, made it to the finals but they were shut out by Taiwan in the final, 5-0. Lansford was a three-sport star (football, basketball, and baseball) at Adrian C. Wilcox High School in Santa Clara. Although he was good enough to earn scholarships to play both football and basketball at the college level, Lansford chose to pursue a career in professional baseball. (Wilcox High later named its baseball field in Lansford’s honor.)

The California Angels selected him in the third round of the amateur draft on June 3, 1975. Carney signed with the Angels, who assigned him to Idaho Falls of the Pioneer League, a rookie league. “After I signed, I had no idea what I was getting into,” said Lansford. “I was sent off to Idaho Falls. It was the first time I was away from my home and family, and if I weren’t homesick enough, I was in a fireproof hotel, all brick, in a room just big enough for a bed. The toilet was inside the closet; the shower was a community shower in the hallway.”2

Lansford was making $500 a month, which barely covered his expenses. Although most players might not consider an injury as fortunate, Lansford did. His left shoulder popped out of its socket, an old football injury. Lansford returned home after just eight games. “I don’t know what would have happened if I’d stayed there.”3

Despite just playing in eight games at Idaho Falls in 1975, Lansford made the jump to Quad Cities of the Class A Midwest League in 1976. Perhaps with his homesickness abated, Lansford led the Angels in home runs (14) and RBI (86) while batting .287. While Lansford’s work at the plate was impressive, his work in the field left room for a lot of improvement. Playing in 111 games at third base, Lansford committed 34 errors in 362 chances for a fielding percentage of .906.

However, Lansford wanted to be a complete player. When he reported to El Paso of the Class AA Texas League, Lansford made that his top priority. “I decided in spring training I wanted to work a little more on my fielding. Mainly, I just try to keep the ball in front of me or knock it down,” said Lansford. “I found I had a lot to learn my first year and thought my defense left a lot to be desired.”4

The extra work paid off and Carney cut down his errors at El Paso (15) and raised his fielding percentage (.955) in 116 games. His offensive production continued to rise, as he slugged 18 home runs, and drove in 94 runs while batting .332.

Lansford leap-frogged the AAA level, joining the California Angels for the 1978 season. The Angels were a veteran club that was managed by Dave Garcia. Dave Chalk was the Angels’ third baseman the year before, but he moved over to shortstop, allowing Lansford to slide into the vacant hot corner slot. He made his major league debut on April 8, 1978, pinch-hitting for Rance Mulliniks against Dave Heaverlo in the bottom of the ninth inning in a 4-2 loss to Oakland. Lansford flew out to right field in the at-bat.

The Angels got out to a 25-21 record through the end of May and Garcia was fired on May 31. The Angels were on a five-game skid at the time of his being ousted and California general manager Buzzie Bavasi was not fan of Garcia’s low-key style of managing or of his tactical decisions.5 Garcia was replaced by Jim Fregosi, one of the great Angel players from the franchise’s earlier years.

Lansford missed a month of playing time from June 11–July 7 when he strained ligaments in his left thumb. The injury was the result of a home-plate collision between Lansford and New York Yankee catcher Mike Heath in the bottom of the ninth inning of a game at Anaheim Stadium. The collision touched off a benches-clearing brawl between the two clubs.

In 121 games, Lansford batted .294. The Angels (87-75) tied Texas for second place in the American League West. Both clubs finished five games behind first-place Kansas City (92-70).

On February 10, 1979, Lansford and his long-time girlfriend Deborah Samora tied the knot in Northern California.

Lansford was having a superb sophomore season, batting .308 at the All-Star break. However, he was passed over for the Midsummer Classic. “Everyone is going to vote for Graig Nettles because of his World Series games,” said Don Baylor. “It’s unfair to Carney. He’s having an All-Star year. The players would vote for Lansford, but because of the ballot-box stuffing in Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles, Kansas City and places like that, he won’t make it.”6

Lansford may have been overlooked for the All-Star squad, but there was no doubting the Angels. They broke the three-year grip the Royals had on the AL West. California (88-74) out-distanced Kansas City (85-77) by three games. In the ALCS, however, Baltimore disposed of California in four games to advance to the World Series.

But if the 1979 season was successful one for the Angels and personally for Lansford, the 1980 season was the direct opposite. Injuries took their toll on the club, and by the All-Star break, they were in the cellar of the AL West, 16½ games behind first place Kansas City. As what often happens when a team is floundering, back-biting and sniping become commonplace, and the team’s issues are made public through the media. General manager Buzzie Bavasi was not above these tactics, often referring to his players as “gutless.”7

Lansford was batting .285 at the end of July, but his average plummeted in August (.218) and September (.232). Bavasi had the solution, ordering Lansford to start wearing glasses. “Every time I’d start to slump, Buzzie would send me to the eye doctor,” said Lansford in a 1981 interview, “and last year [1980] the guy said one eye couldn’t carry the other anymore and that I should start wearing glasses. I just couldn’t get used to them in the middle of the season.”8

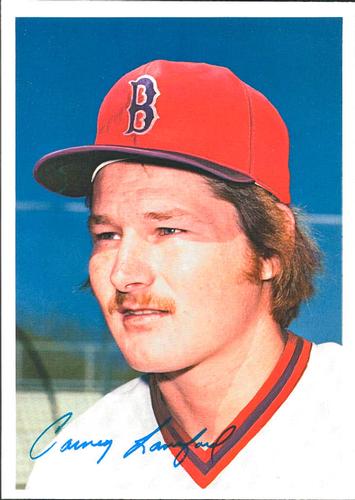

At the 1980 winter meetings in Dallas, the Angels and Red Sox pulled off a five-player swap on December 10. Boston sent shortstop Rick Burleson and third baseman Butch Hobson to California for pitcher Mark Clear, outfielder Rick Miller, and Lansford.

“They didn’t want to give up Lansford, but they said they had to have Burleson,” said Boston manager Ralph Houk, “we said we had to have Lansford, and we built it that way. It’s a deal that was fun to work on because it made sense.”9

The Red Sox were a perennial contender in the AL East. Jim Rice, Dwight Evans, Glenn Hoffman, Jerry Remy, and an aging Carl Yastrzemski formed a solid nucleus. Lansford and Miller were welcome additions to the mix.

The 1980 season began with a rather dark cloud hanging above major league baseball. The threat of a players’ strike had settled over baseball beginning in 1980 and carried over to the 1981 season. The MLB players’ union disagreed with management over free-agent compensation. The players walked out on June 12, 1981. The strike was eventually settled on July 31 after it had forced the cancellation of 713 games.

The 1981 season was divided into two halves for each division. The playoffs were expanded by one round, with each division winner from the first half playing the second half winner. Unfortunately for Boston, they did not finish in first place in either half. Lansford led the league in batting with a .336 average (134-for-399) as he easily topped Seattle’s Tom Paciorek (.326). One of the highlights for Lansford was a career-best 5-for-5 day against the Royals on May 17, 1981.

The 1981 season was divided into two halves for each division. The playoffs were expanded by one round, with each division winner from the first half playing the second half winner. Unfortunately for Boston, they did not finish in first place in either half. Lansford led the league in batting with a .336 average (134-for-399) as he easily topped Seattle’s Tom Paciorek (.326). One of the highlights for Lansford was a career-best 5-for-5 day against the Royals on May 17, 1981.

On June 23, 1982, the Red Sox hosted Detroit. Although Boston won 10-4, the victory was a costly one. With two down in the bottom of the third inning, Lansford smashed a line drive off the facing of the Red Sox bullpen in right-center field. Lansford reached third base and was waved home by third-base coach Eddie Yost. However, the relay from Detroit shortstop Alan Trammell beat Lansford to the plate. He collided with catcher Lance Parrish, spraining his left ankle and suffering a torn ligament. Lansford was batting .288 at the time.

Wade Boggs stepped in to replace Lansford. “I’ve got an awful lot of confidence in him,” Lansford said of Boggs. “He’s a darn good hitter who hasn’t really had a chance to get into any kind of groove this year. But once he plays a few games, I think he’s really going to show people something.”10

Indeed, Lansford may have had Swami-like visions. He returned to the lineup a month later, batting .301 for the season. Boggs hit .349 in 104 games and thus began a career that ended in the Hall of Fame. Some thought that this might be a modern-day tale of the Wally Pipp – Lou Gehrig incident from 1925. Gehrig stepped in for the stricken Pipp at first base, and he never left the lineup. Pipp was eventually sold to Cincinnati.

Sure enough, at the winter meetings in Honolulu, the Red Sox and A’s made the biggest splash on the first day. On December 6, 1982, Boston sent Lansford, outfielder Garry Hancock, and minor-league pitcher Jerry King to Oakland for outfielder Tony Armas and catcher Jeff Newman.

The emergence and potential of Boggs was certainly a motivating factor in trading Lansford. But also, Lansford was approaching free agency in another year. Lansford lost his arbitration hearing prior to the 1982 season. He was seeking a salary of $650,000, but the arbiter ruled in the Red Sox favor, a salary of $440,000. Lansford still received a big increase of 1981, but it was believed that he would be seeking a contract in the $1 million range.

The trade held an extra bonus for Lansford as he was headed home. “Tony is a player you hate to lose,” said Oakland president Roy Eisenhardt. “But we had to improve our infield. We got exactly the player we wanted, as good a third baseman as there is in the game. We’re set at third now for at least five years.”11

As for the prospect of signing Lansford to a deal, Eisenhardt did not flinch. “That’s a risk we assume,” he said. “I will pay Carney what I think is fair market value. And I plan to do it before February (when Lansford could take the A’s to arbitration).”12 True to his word, Eisenhardt got Lansford’s name on the dotted line of a contract, a one-year deal worth a reported $700,000.13

Lansford was not the only new addition to the Athletics. Steve Boros was hired as the manager, replacing Billy Martin who was fired after the 1982 season. It was the first managing position for Boros after seven years as a major-league coach.

Unfortunately, for Carney and Deborah Lansford, tragedy struck on April 10. Their first child, two-year old son Nicholas, died after a long illness. Lansford took a leave of absence from the team.

When he returned, he sprained his wrist against Baltimore on April 27. When he came back two weeks later, but the wrist still gave him problems. Lansford went on the disabled list and did not return to the club until June 14. He re-injured his left ankle curing a doubleheader at Cleveland on August 24. Although Lansford did not remember how he injured the ankle, the pain became too severe in the second game. He missed another month of the season, returning for two games at the end of the season.

Lansford performed well when he was healthy, hitting .308 in 80 games. He stroked 10 home runs and drove in 45 runs. Oakland finished the year in fourth place in the AL West with a 74-88 record, a full 25 games out of first place.

The A’s got off to a 20-24 record in 1984, and Boros was replaced with Jackie Moore. Lansford played a full season, leading the team in hitting with a .300 average in 151 games. Oakland performed a little better under Moore (57-61) but finished in fourth place again with a 77-85 record.

In 1985, Lansford’s season was once again shortened by injury. On July 25, Milwaukee’s Pete Ladd hit Lansford on the right wrist with a pitch, causing a hairline fracture. At the time of the injury, the A’s (49-46) were in third place of the AL West, seven games behind division-leading California. “It’s especially tough at this time,” said Lansford. “We are going to be playing the Angels at home. These are big games. This is what you wait all season for.”14 Lansford, who was batting .282 at the time of the injury, was also amid a streak of 47 errorless games. Although Lansford returned to the club a month later, the wrist continued to give him pain and he was shut down for the season.

Although Oakland finished 10 games under (76-86) .500 in 1986, general manager Sandy Alderson was slowly putting the pieces together of a championship club. Few people may have realized it at the time, but rookie Jose Canseco (33 home runs and 117 RBI) in 1986 was providing just a prelude to what his career would be. Two players called up late in the season were Mark McGwire and Terry Steinbach.

But the most important change came on July 7. Tony La Russa was hired to replace Moore as the A’s manager (Jeff Newman served as interim manager for 10 games). La Russa had been fired three weeks earlier by the White Sox. He had some success in Chicago, winning the AL West in 1983, and he finished in third place three other seasons.

The focus of the A’s was the “Bash Brothers,” Canseco and McGwire, and for good reason. McGwire set a rookie home run record with 49 home runs in 1987 while Canseco added 31. Lansford tied his career-best with 19 and batted .289 (tied with McGwire for the team best).

One of the greatest conversion projects was taking place in the Bay area in 1987. Dennis Eckersley was acquired (with infielder Dan Rohn) in the off-season from the Chicago Cubs. The price tag was three minor league players who, as it turned out, never made it to the major leagues. Eckersley had battled a sore back and alcoholism since winning 20 games for Boston in 1978. His career was up-and down when La Russa and Oakland pitching coach Dave Duncan moved him to the bullpen, and eventually the role of closer. It was a transition that led to enshrinement into the Hall of Fame.

Oakland went from an 81-81 record in 1987 to a 104-58 finish in 1988. The roster was further solidified by the acquisition of center fielder Dave Henderson from San Francisco. Hendu was a terrific fielder and a capable batsman with some power. Another addition was Dave Parker, a veteran right fielder in the National League who would fit in as a designated hitter with Oakland.

Also added was veteran Don Baylor, who assessed Lansford in his later book as “Mr. Intensity. He ranks in my top five base-runners when it comes to knowledge and breaking up double players. Carney is a workaholic and an uncanny fielder. When he came up with the Angels, they tried to plant a lot of negative thoughts in his head, telling him he didn’t have lateral range and needed glasses. Fortunately, Carney did not listen. Instead, he made himself into one of the brilliant third basemen of our time. He knows every inch of ground in the extremely spacious foul territory in Oakland. He knows every other park, as if he’s played in each his entire career. You can’t learn to be that good. It’s instinctive. Carney is also good people, intelligent, caring, a guy who would walk through a wall to help a friend.”15

Walt Weiss grabbed the starting shortstop position and won the AL Rookie of the Year award in 1988. He was the third consecutive A’s player to be so honored. Lansford batted .279 and was selected to the All-Star Game for the only time in his career, July 12, 1988, at Riverfront Stadium.

After defeating Boston in the ALCS, the A’s faced the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. Oakland was deemed the heavy favorite (8½-2)16. But the A’s were upset by the Dodgers in five games.

Rickey Henderson returned to Oakland for his second tour of duty on June 21, 1989, acquired through a trade with the Yankees. He appeared in 85 games and still led the club with 52 steals. It was validation on how Henderson could change the outcome of a game with his baserunning.

Lansford was second on the team with 37 stolen bases, a career high, and he led the team in hitting with a .336 average. The A’s suffered a number of injuries that season, but Lansford was healthy and steady, even filling in at first base when McGwire was disabled. No other Oakland player hit over .300 in 1989. He was selected to The Sporting News AL All-Star team.

Oakland (99-63) won their second straight divisional title in 1989 and dispatched Toronto in five games in the ALCS. Lansford led the hit parade against the Blue Jays, batting .455 (5-for-11) with four RBI. The Athletics faced their neighbors across the bay, the San Francisco Giants, in the World Series. Again, the A’s were the prohibitive favorite at 9-11 odds.17

Oakland won the first two games handily at home before the series shifted to Candlestick Park. Before Game Three could get underway, the Bay area was struck on Tuesday, October 17, at 5:04 p.m. by the legendary Loma Prieta earthquake. The stadium shook and was evacuated without further damage. But that was not the case with the rest of the area as the earthquake left destruction in its wake.

The earthquake registered a 7.0 on the Richter scale. An aftershock the following morning at 3:14 AM registered a 5.0.18 Overall, damage was reported in seven counties:

- 264 people died.

- 972 people injured.

- 250 buildings damaged.

- Four buildings collapsed.

- 1,300 homes in Oakland damaged, 10 collapsed.

- Power lines and water resources were cut.19

The A’s players drove their families home from Candlestick Park, often still in uniform, and the team moved to their spring training facilities in Phoenix stay in shape. After a week, the series resumed. The games had an anticlimactic feel as the series was now a secondary event. Oakland steamrolled over the Giants to sweep them in four extremely one-sided games. “After last year’s disappointing loss to the Dodgers, the most gratifying part about winning this year was showing the whole world what the A’s are really like,”20 said Lansford. The Oakland third baseman led the A’s in hitting once again, as he batted .438 (7-16) with one home run and four RBI.

Oakland won their third consecutive pennant in 1990, sweeping Boston. The shoe was on the other foot when their opponent in the World Series, the Cincinnati Reds, swept the A’s. Jose Rijo beat Dave Stewart twice and was selected as the Most Valuable Player.

On December 31, 1990, Lansford was involved in a snowmobile accident on his ranch in Oregon. He suffered severe cartilage and some ligament damage to his left knee and right shoulder. Lansford returned to the A’s lineup on July 19. But after a total of five games his left knee began to ache, and he was put on the shelf for the season.

The Athletics (84-78) slumped to fourth place in the AL West in 1991. With the nucleus of the club intact, Oakland posted a 96-66 record and reclaimed the AL West title over second-place Minnesota. One highlight for Lansford came on June 13, at home against Texas. In the first inning, Lansford smacked his first home run of the season. The solo shot was a big one, it was also the 2,000th hit of his career. “I told the clubhouse guy, I don’t care what you have to give this guy for the ball, I want it. I’ll give up my Porsche. I want that ball,”21 said Carney. Lansford batted .262 in 1992. Oakland was eliminated by Toronto in the ALCS in six games.

Lansford retired after the 1992 season. “It took so long for me to take off my uniform for the last time,” said Lansford. “It’s not as easy as I thought it would be. It’s time for me to move on and spend some time with my kids.”22 Over 16 seasons, his lifetime batting average was .290 with 2,074 hits, 151 home runs and 874 RBI. He fielded his third base position at a .966 clip.

In 1994, Lansford had a minor role in the remake of the movie, Angels in the Outfield. Lansford also served a technical advisor for the movie, teaching actors how to hit and throw.

Although Lansford stated that he would miss the game and his teammates, he did not stray from the game for too long. He joined La Russa’s coaching staff in Oakland (1994-1995) and again in St. Louis (1997-1998). After a stint managing Edmonton in the Pacific Coast League (1999), Lansford rejoined the majors with hitting coach positions in San Francisco (2008-2009) and Colorado (2011-2012).

Lansford had two sons who played professional baseball. His son Jared, a pitcher, was drafted by Oakland in the second round of the MLB June Amateur Draft. He played as high as Triple-A in Oakland’s minor-league chain. He also played professionally in China, Italy, and in the independent Atlantic League. His other son, Josh, was drafted by the Chicago Cubs in the sixth round of the 2006 MLB June Amateur Draft. Also a pitcher, Josh spent two years in the Cubs organization, two in the Athletics’ chain, and then three years playing for the Long Island Ducks in the independent Atlantic League. Josh and Jared were teammates on the Ducks in 2012.

Today, Carney Lansford is retired and living in Mesa, Arizona. His reputation as one of the best-hitting third basemen of his generation and his role as a key to the Athletics’ three straight pennants highlight his career. He overcame serious injuries and persevered, making the name Carney Lansford a wonderful reminder to all A’s fans.

Last revised: June 24, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by James Forr and David H. Lippman and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Mrs. Lansford claimed direct descent from the famed English naval hero, Sir Francis Drake, and the Oakland Athletics dutifully repeated the claim in their media guides. Asked in a 1984 Yankee Stadium interview by UPI sportswriter and this article’s editor, David H. Lippman, about the claim, Lansford said, “That’s what she tells me. She says it’s true. She didn’t go into it in detail.”

2 Peter Gammons, “Fair Trade,” Boston Globe, June 13, 1981: 30.

3 Gammons, June 13, 1981: 30.

4 Harry Readel, “Insomniac Lansford Dreams of Angels,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1977: 58.

5 Scott Ostler, “Message to Garcia: You’re Fired; Fregosi is Hired,” Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1978: 3-1.

6 Dick Miller, “Slugger Baylor—No. 1 Gun In Angel Arsenal,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1979: 18.

7 Gammons, June 13, 1981: 30.

8 Gammons, June 13, 1981: 30.

9 Peter Gammon, “Burleson, Hobson, Go,” Boston Globe, December 11, 1980: 55.

10 Steve Harris, “Lansford see out for 3 weeks,” Boston Herald, June 25, 1982: 50

11 Kit Stier, “Lansford Plugs A’s Biggest Gap,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1982: 53.

12 Ibid.

13 “A’s Sign Murphy, Lansford for ’83,” San Francisco Examiner, January 26, 1983: F2.

14 Kit Stier, “Lansford’s Wrist Toughest Casualty,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1985: 22.

15 Don Baylor, Nothing But the Truth, A Baseball Life, by Don Baylor with Claire Smith, St. Martin’s Press, 1989, page 292.

16 J. McCarthy, “The Latest Line,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 15, 1988: C -2.

17 J. McCarthy, “The Latest Line,” San Francisco Examiner, October 13, 1989: B-16.

18 Lance Williams, “After Quake, a New World,” San Francisco Examiner, October 19, 1989: A-1.

19 Damage Assessment, County By County, San Francisco Examiner, October 19, 1989: A-9.

20 Kit Stier, “How the A’s Went from Zeroes to Heroes,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1989: 53.

21 Frank Blackman, “Heroes Galore in A’s Victory,” San Francisco Examiner, June 14, 1992: C-5.

22 “Lansford last to leave as he gangs up his glove,” Oneonta Star, October 10, 1992, Article from Player’s Hall of Fame Clip File.

Full Name

Carney Ray Lansford

Born

February 7, 1957 at San Jose, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.