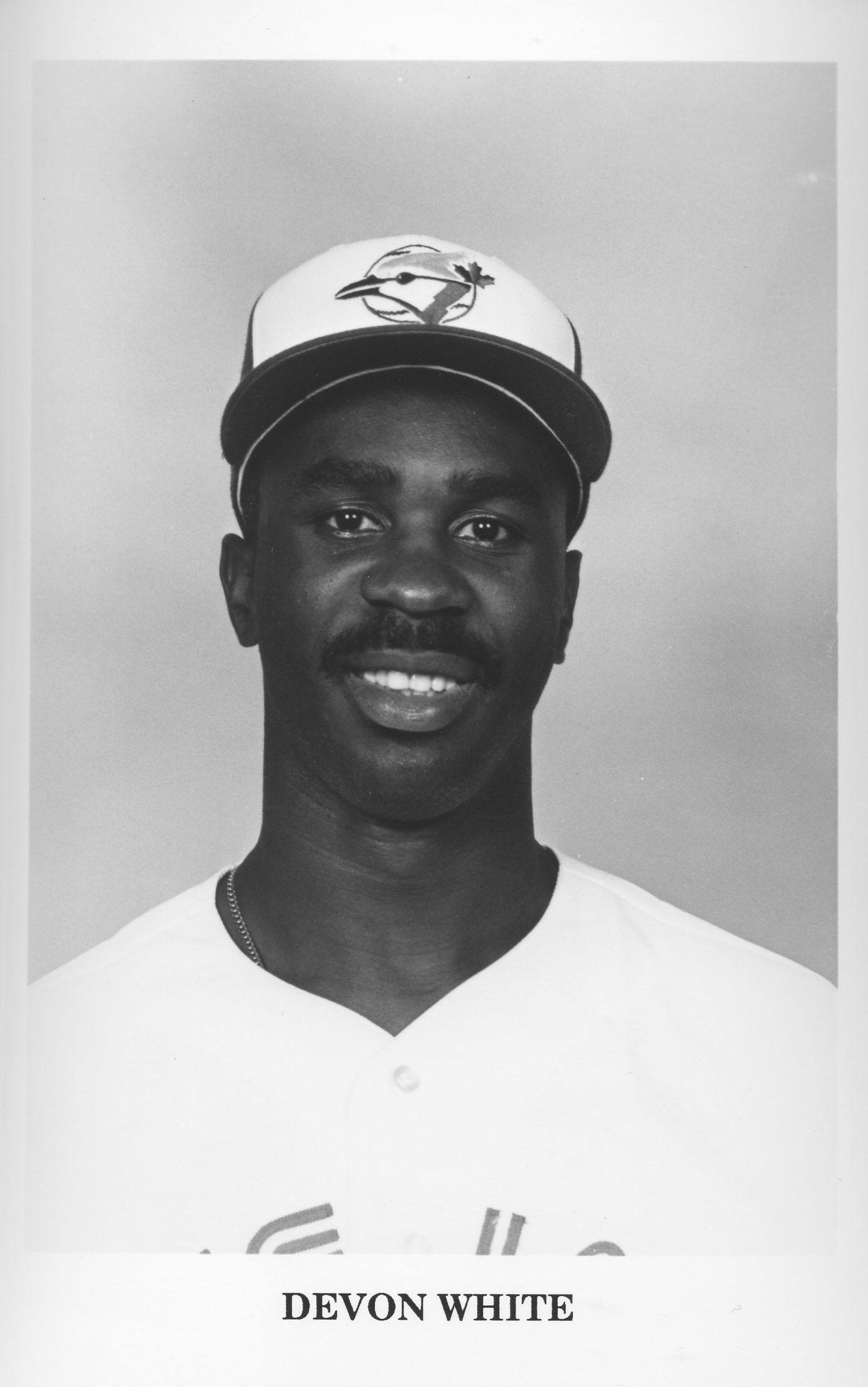

Devon White

Seventy percent of the world is covered by water, the rest is covered by Devon White. Considered one of the best defensive outfielders to play the game, White was a human highlight reel who worked tirelessly to hone his craft. He was a raw athlete when he was drafted as a third baseman in the sixth round of the 1981 draft by the California Angels, but he had all the makings of becoming a big-league star. He could change the outcome of a game with a single leap and on occasion hit for power. He was pragmatic, driven, and self-aware. “I think when a ball is in the ballpark and it’s not a hard line drive, I’m going to get it,” he once said.1

Seventy percent of the world is covered by water, the rest is covered by Devon White. Considered one of the best defensive outfielders to play the game, White was a human highlight reel who worked tirelessly to hone his craft. He was a raw athlete when he was drafted as a third baseman in the sixth round of the 1981 draft by the California Angels, but he had all the makings of becoming a big-league star. He could change the outcome of a game with a single leap and on occasion hit for power. He was pragmatic, driven, and self-aware. “I think when a ball is in the ballpark and it’s not a hard line drive, I’m going to get it,” he once said.1

Devon Markes Whyte was born on December 29, 1962, in Kingston, Jamaica. He is just one of five major-league players born in Jamaica, including future teammate Chili Davis. His family immigrated to New York when he was 9 years old. Upon his arrival, his last name was documented incorrectly as “White.” In 2003 he changed it back to Whyte at the request of his three children, one of whom, Davellyn, played three seasons in the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) with the San Antonio Stars.

In Kingston, White played cricket and soccer. In the 1970s United States, the closest sports to cricket were stickball and baseball. White initially learned the game from his father by watching the Mets and Yankees on television,2 but did not start playing until he was a teenager. “I was more involved with basketball,” he said. “Baseball was something I played with some of my Spanish friends, just to have something to do.”3

White excelled as a ballplayer at Park West High School in Manhattan, where he lettered all four years and hit .330 as a senior. And although basketball was his first true love, the chance of playing professional baseball was too enticing to pass up.4 “I even had a scholarship offer to play basketball and baseball at Oklahoma State, but once I got drafted by the Angels, baseball became my favorite sport,” he said.5

White’s 1981 scouting report described him as “thin, lanky and broad across top with room to fill out … built like Rod Carew. Has all the tools, arm, speed, quick bat and reflexes to be fine professional ballplayer. Due to range athlete may be better suited to play 2B.”6 But his first minor-league manager, Joe Maddon, quickly moved him to outfield. Maddon noted, “[He] couldn’t hit a lick. Good thing we put him in the outfield and stuck with him.”7

White was a project for the California Angels. Manager Gene Mauch recalled that the first time he saw White play in 1981, “he was the rawest professional baseball player I have ever seen. … I mean the rawest. … He could only do one thing like a big-league ballplayer, and that was run.”8

To White’s credit, he was driven to improve his hitting. Mauch noted White’s commitment as the guy who asks, “What do you want me to do, how much do you want me to do and for how long do you want me to do it? And if I don’t think I’ve got enough of it, I’ll have some more.”9

White’s minor-league hitting instructor, Rick Down, said that White was willing to work on his craft including becoming a better bunter, studying Rod Carew, even on his own time. He said, “I don’t see Devon ever being in an extensive slump, because he can put the ball down.”10

There was a lot to be excited about White. Scouts referred to him as “Willie Wilson with power, a mirror image of Willie Davis in his prime, and a Gary Pettis with better bat control.”11 Rick Down thought White could be a 20-home run, 60-stolen-base threat. High praise for a youngster for whom baseball was his least favorite sport.12

The road to becoming a big-leaguer was arduous for White. Between 1981 and 1985 he played throughout the Angels farm system, with stops in Danville, Nashua, Peoria, Redwood, Midland, and eventually to Edmonton of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League.

By 1985, White flashed glimpses of greatness when he stole 59 bases in 136 games with Midland and Edmonton, leading both teams. His performance in Edmonton earned him a brief call-up to the California Angels at the end of the season. He managed just one hit in nine plate appearances and three strikeouts. In 37 innings in the outfield, he had 11 putouts and one assist and did not commit an error.

White returned to Edmonton in 1986 and led the team in stolen bases, triples, and runs. He slashed .291/.339/.479 and earned another late season call-up that made him eligible for his first postseason.13 It was an exciting opportunity for the young ballplayer, but White was realistic about it, saying, “I’m just trying to help the club in any way I can, just trying to learn. But, yeah, you can’t help but think about that (playoffs) when you’re on a team like this.”14

This was a much different experience than in 1985. “I think last year when I came up, I was more in awe of everything,” White said. “This time around I’m just trying to concentrate on doing my job, to learn the fine points of the game.”15 In three games, White was a defensive substitute, pinch-runner, and defensive replacement; in Game Five he had one hit in two at-bats The Angels lost to the Boston Red Sox in the American League Championship Series, four games to three.

The next season, 1987, was White’s first full season at the major-league level. He had a strong spring training, hitting .375 and leading the Angels in RBIs. Playing primarily in right field during the regular season, White led the Angels in hits with 168, stolen bases with 32, and a 5.6 WAR. He tied Wally Joyner with 33 doubles and Jack Howell with 5 triples. White also led the team in strikeouts with 135 while walking only 39 times.

The switch-hitter finished his rookie campaign slashing .263/.306/.443, hitting 24 home runs and amassing 87 RBIs. He led American League outfielders with 424 putouts. He finished fifth in the AL Rookie of the Year voting behind Mark McGwire, Kevin Seitzer, Matt Nokes, and Mike Greenwell.

Coming off his rookie season, White was introduced to the realities of professional baseball – contract negotiations. He wanted a new contract, but the Angels were prepared to renew it as they had in previous years. White was not happy. “So far, negotiating contracts hasn’t been much fun at all,” he said. He had his sights on earning “somewhere between Kevin Seitzer ($175,000) and Mike Greenwell ($205,000), with some kind of incentives.”16

The Angels were basing their contract decisions on Wally Joyner’s second-season contract, which irked White. “They’re comparing me with someone on my team who is not an outfielder. … If they’re going to do that, I feel they should at least include some incentives.”17 White earned $185,000 in 1988 without incentives.

Before the 1988 season, Gary Pettis was traded to the Detroit Tigers, making White the full-time center fielder. In the first 29 games he hit .245 with an OBP of .312 and four stolen bases before arthroscopic shoulder surgery sidelined him for a month.18 His absence was palpable. “With the outfield we had there for a while, the guys in the bullpen made up a little lottery to see which position would make the first error in which inning. We gave it up when Devo came back,” said reliever Greg Minton. When White returned to the lineup on June 10, the Angels were in seventh place in the West. By July 22, they were 23-13, good enough for fourth place.

The 1988 season was also the first time that White led off in the majors, though it did not necessarily suit his offensive style. “I’d rather strike out on a ball in the dirt and run to first than walk. I hate to walk,” he professed, not exactly the mindset of the prototypical leadoff hitter.19

Angels manager Cookie Rojas moved White to the leadoff position on July 7 and over the next 11 games he scored 10 runs, hit two home runs, and drove in nine runs. The Angels went 8-3 during that stretch. And despite his opposition to the role, White would do what the team needed, commenting, “If we continue to win and I’m doing the job at leadoff, then so be it.”20 That defined White, who did what was best for his team. Although his offensive numbers declined in 1988, his defense was the best in the game, which earned him his first of seven Gold Gloves.

White began the 1989 season in contract talks again. With teammates Chili Davis and Wally Joyner receiving new and much larger contracts, White expected the same. “I think I’ve paid my dues,” he said. “But I’m not going to cause any trouble or leave or anything like that. … Maybe next year I can take it to them in arbitration.”21 He signed a one-year contract worth $380,000, $600,000 less than Joyner.

For the first half of the season, White slashed .259/.292/.427, hitting nine home runs and stealing 25 bases. He hit a career-high 13 triples, earning his first AL All-Star selection as a reserve center fielder behind Kirby Puckett. White also won his second Gold Glove in as many seasons.

But arguably the most memorable moment of White’s 1989 season was on September 9 against the Boston Red Sox, when he put on a baserunning display for the ages and quite literally stole the game from the Red Sox.

In the bottom of the sixth inning, with Boston leading 5-3, White singled to left field, driving in Claudell Washington and closing the gap to 5-4. White then stole second. Then he stole third. And with permission from manager Doug Rader, White stole home. “He’s asked to do it before, and it wasn’t the appropriate time. It was appropriate tonight. … We needed to generate some runs. We needed some excitement,” Rader said.22

White said that he took “a big chance, stealing home with a right-handed batter at the plate. He [Johnny Ray] doesn’t know what I’m doing.”23 But his decision worked in his favor because Ray blocked catcher Rich Gedman’s view of the third-base line and before Gedman realized it, White was sliding into home, tying the game, 5-5. Two innings later, White added his fourth steal by taking second base, sparking an eighth-inning rally that would give the Angels an 8-5 lead and the win.24 White finished the season with a career-high 44 stolen bases.

The 1990 season was one to forget for White. He was demoted to Edmonton in July after hitting a paltry .213 and striking out 71 times in 73 games. He earned his way back to the Angels by hitting .364/.582/1.017 with four stolen bases and four triples in 14 games. But he could not keep up that momentum. He finished the season striking out 116 times, the third 100-strikeout performance of his career.

After the 1990 season, the writing was on the wall. With multiple public contract disputes and a demotion to Triple A, it did not appear that California had built White into its long-term plans. The Angels traded their Gold Glove outfielder to the Toronto Blue Jays along with pitchers Willie Fraser and Marcus Moore for outfielder Junior Felix, infielder Luis Sojo, and minor-league catcher Ken Rivers.

White was thrilled with the move. Reflecting on the trade, he said, “At the time, I wasn’t happy anymore in California. There was a lot of misleading information out there, saying I was a bad apple and things like that … and I don’t know why that was.”25

White’s lack of production in 1990 was of no concern to Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick. “We got him for defense. We’re not worried about his hitting. We feel we have enough to carry Devon White, no matter what he hits.” Three days later, the Jays acquired future Hall of Famer Roberto Alomar and Joe Carter from the San Diego Padres for Fred McGriffand fan favorite Tony Fernandez.

Moving to Canada was a revelation for White’s career, both personally and professionally. He felt at home in Toronto because of the diverse Jamaican community. His fondest memories of his time in Toronto were the fans and seeing SkyDome (later renamed Rogers Centre) full every night. From 1991-93, 4 million26 fans packed SkyDome each season, ranking first among AL teams. White is still recognized by fans when he visits Toronto.27

Over five seasons with the Blue Jays, he hit .270/.327/.432 with an OPS+ of 102, a significant improvement from his four years in California. His first season with Toronto was arguably the best of his career. He slashed .282/.342/.455, earned an OPS+ of 116, the highest of his career, and had 181 hits, also a career high (seven shy of Roberto Alomar’s team high). He was second and third on the team with 10 triples, and 40 doubles. White also led the AL with 439 putouts. He earned his third Gold Glove.

The 1991 season was a good one for White. His daughter, Davellyn, was born in the spring and he led the Jays to first place in the AL East and ranked first among outfielders in fielding percentage. Although they lost to the Minnesota Twins 4 games to 1 in the AL Championship Series, White finished nearly atop all offensive categories for the Jays, hitting .364/.417/.409 with three stolen bases and eight hits.

The 1992 season was the apex for both White and the Blue Jays. Toronto won the AL East again and defeated the Oakland Athletics in the ALCS to earn its first berth in the World Series, against the Atlanta Braves. White continued to dazzle on defense, starting one of the greatest plays in World Series history and the hallmark play of his career.28

In the top of the fourth inning of Game Three, with the game scoreless, Atlanta’s David Justice smacked a ball into deep center field with Terry Pendleton on first and Deion Sanders on second. White tracked the seemingly uncatchable ball, leaped, and made a backhanded grab, plucking the would-be extra-base hit out of the air, and crashed into the wall for out number one. White then quickly threw to the cutoff man, Alomar, who tossed to John Olerud at first base. Thinking it was a base hit, Pendleton passed Sanders at second base for an automatic second out. Sanders then tagged up from second and Olerud rifled it to Kelly Gruber at third, catching Sanders in a rundown. Gruber chased Sanders back to second, dived and lightly brushed a tag on Sanders’ ankle, though second-base umpire Bob Davidson missed the tag by Gruber, ruling Sanders safe at second base.29

When asked about the play, White said, “People ask, do you wish it was a triple play? And I say no. The truth of the matter is we went on and won the World Series, so if that would have happened, everything changes, right?”30 The Blue Jays went on to win their first World Series in six games.

In 1993 White earned his fifth Gold Glove and second All-Star appearance, as a reserve, behind Ken Griffey Jr. He also helped propel the Jays to their second consecutive World Series title. White was a standout for Toronto in the ALCS against the Chicago White Sox. In six games, he led the team with 12 hits and a .444 batting average, and finished second to Paul Molitor in on- base and slugging percentage, .464 and .667 respectively. Against the Philadelphia Phillies in the World Series, he helped beat them with his speed, legging out three doubles, a team high, and two triples in six games.

White picked up two more Gold Gloves in the 1994 and 1995 seasons. The 1995 season was White’s final one with the Jays. A free agent, he signed a three-year, $9.9 million contract with the Florida Marlins.31 Joe Carter called White’s departure “by far the biggest loss. What he brings to a club as a leadoff guy and the best center fielder in baseball, you just can’t replace it.”32

Florida was a perfect location for White; he would be playing closer to Jamaica and have an opportunity to take on a leadership role with the team. “I’ve noticed that we have a lot of young ball players over here and I’m here to help them in every which way I can,” he said.33

White could still fly as a 33-year-old veteran. In 1996 he led the Marlins in stolen bases with 22 and 37 doubles, which was second only to Steve Finley among National League center fielders. And his defense was still a strong asset. Joe Carter said, “I’m just thankful he’s in the National League, I didn’t want him running down our stuff.” Blue Jays manager Cito Gaston commented, “Just when you think the ball is not going to be caught, Devon somehow kicks into a second gear and gets to the ball.”34

In 1997 White was hampered by injury and appeared in only 74 games. He hit just .215 and stole only two bases in 16 playoff games. The highlight of his postseason came in Game Three of the Division Series against the San Francisco Giants. The Marlins were up two games to none and were looking to close out the Giants at home. After going hitless in the first two games, White hit a grand slam in the bottom of the sixth inning, giving the Marlins a 4-1 lead and eventually winning the game 6-2, sweeping the Giants.

In the World Series against the Cleveland Indians, which the Marlins won in seven games, White led the team with three doubles and 10 strikeouts.

In 1998 the Marlins brass cleaned house and sent White to the expansion Arizona Diamondbacks. The 35-year-old finished atop nearly every offensive category, including hits, home runs, and stolen bases, on a team that went 30-58 in the first half of the season. He was the inaugural Diamondbacks All-Star, the third honor of his career. White replaced Tony Gwynn in the fifth inning of the All-Star Game, and went 3-for-3 with a triple, a run, and two singles.35 A free agent after the season, White signed a three-year, $12.4 million contract with Los Angeles Dodgers.

White’s 1999 season production fell below his career average, and he was nowhere near the top of the team rankings as in prior years. He was an aging fielder who could no longer rely on speed and power to impact the game. Coming into the 2000 season, an opposing team’s scout noted that “Devon White is a problem in center field. He doesn’t dive for balls or come to play every day.”36

White suffered a partial tear of his left rotator cuff diving for a ball in a game in May. He was placed on the 15-day disabled list. He played just 47 more games that season.

In the final year of his contract, White was relegated to fourth-outfielder duties, likely for a number of reasons, including injury risk, performance, and to make room for the newly acquired Tom Goodwin.37 White was understandably unhappy and requested a trade. On February 24, 2001, he was sent to the Milwaukee Brewers for Marquis Grissom and Ruddy Lugo.38

The trade to Milwaukee seemed like a fresh start for the veteran. Although he would be used as a fourth outfielder, he was happy to be in Milwaukee, said Brewers general manager Dean Taylor.39 White appeared in 126 games, starting 86 in center field and 13 in left field, and pinch-hitting 31 times. Milwaukee did not pick up his option for the following season.

After 17 seasons with six teams, three World Series championships, seven Gold Gloves, and three All-Star Game appearances, White called it quits. The switch-hitter finished his career with 1,934 hits, 208 home runs, a .263 batting average, and 346 stolen bases, and ranks 35th all-time with 4,739 putouts overall.

White was eligible for the Hall of Fame in 2007 and despite receiving seven Gold Gloves, he did not receive a single vote. He is one of only two players (Garry Maddox) to earn seven Gold Glove Awards and no Hall of Fame votes.40Speaking of Gold Gloves, White used the same mitt his entire career. “You take care of something, and it takes care of you,” he said. “It took care of me for 17 years.”41

White pursued coaching in retirement. Between 2008 and 2011 he was the outfield and baserunning coordinator for the Washington Nationals farm system, then moved to the Chicago White Sox as minor-league baserunning coordinator in 2011 and 2012.

But White’s heart was still in Toronto. He wanted to coach in the Jays system, so he stayed close to the organization by volunteering with the Jays Care Foundation and coached at the Tournament 12 event for Top Canadian high-school prospects. Yet his efforts went unnoticed. “I did a lot for the organization as an alumni in that respect, so I was always around. I was doing it for a long time.” But he felt that the general manager, Alex Anthopoulos, was dismissive of him. “Nothing against Alex, but he wasn’t an alumni guy. … I spoke to him when he was an assistant GM, and the word was, if something opened up, he’d let me know. But I have to say he never responded to any of my emails.”42

White persisted, and applied for all available opportunities. Finally, in 2017, the Jays’ Triple-A affiliate, the Buffalo Bisons, named him hitting coach. “I just wanted to be in the game,” he said. “When you played as many years as I did, I feel like you could take any job that’s available. … I’ve always talked about hitting with other organizations when I was there. I helped out with the outfield and just the mental aspects of hitting and getting prepared. So, it’s nothing new to me.”43 In 2018 the Bisons named White the position coach, where he has remained as of the 2022 season. In this role, White works with the Bison outfielders and teaches on base running. In 2021, the Bisons finished the season with 117 stolen bases, ranking seventh in Triple-A.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and mlb.com.

Notes

1 Kristina Rutherford, “The Interview, Devon White,” Sportsnet, https://www.sportsnet.ca/baseball/mlb/interview-devon-white-willie-mays-world-series-best-catch/, accessed January 17, 2022.

2 Ed Odeven, “Q&A flashback: a 1998 interview with MLB outfielder Devon White.” https://edodevenreporting.com/2019/08/13/qa-flashback-a-1998-interview-with-mlb-outfielder-devon-white/ accessed January 17, 2022.

3 Mike Penner, “The Project: Devon White Was Given the Gift of Great Speed – and the Grit to Work Hard,” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 1987.

4 Ken Rodriguez, “Sweet Homecoming,” NBA.com, https://www.nba.com/spurs/features/130807_whyte, accessed January 18, 2022.

5 Gerald Scott, “Devon White Hopes for a One-Way Trip to Angels This Time,” Los Angeles Times, September 4, 1986.

6 This report was provided to SABR by Roland Hemond, who procured it on behalf of the Scout of the Year Foundation and used it in the Diamond Mines Exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2013.

7 Steve Wulf, “The Gnome,” ESPN.com https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/9727219/a-usual-day-unusual-life-tampa-bay-rays-manager-joe-maddon. See also, Tim Hagerty, “When Joe Maddon Was a 27-Year-Old Manager,” The Sporting News, https://www.sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/joe-maddon-idaho-falls-angels-27-year-old-manager/1eqhcmjomm8li1qgpx976w7mgy. Both articlesaccessed February 1, 2022.

8 Penner, “The Project.”

9 “The Project.”

10 “The Project.”

11 “The Project.”

12 “The Project.”

13 Scott, “Devon White Hopes for a One-Way Trip to Angels This Time.”

14 Scott.

15 Scott.

16 Mike Penner, “Angels: Devon White Wants Some Incentives for 1988,” Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1988.

17 “Angels: Devon White Wants Some Incentives for 1988.”

18 John Weyler, “In the Groove: Though He’s a Reluctant Leadoff Hitter, White Helps Stabilize Angel Outfield and Lead Team’s Resurgence,” Los Angeles Times, July 22, 1988.

19 Penner, “White Lightning.”

20 “In the Groove.”

21 Mike Terry, “Davis, Joyner Happiest Campers at Angels’ Spring Base,” San Bernadino Sun, February 23, 1989.

22 Mike Penner, “White Pulls Fast One on Red Sox, 8-5,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1989.

23 Penner, “White Pulls Fast One on Red Sox, 8-5.”

24 Penner, “White Pulls Fast One on Red Sox, 8-5.”

25 Rutherford.

26 Toronto was on pace to have just under 4 million fans in 1994 but the strike canceled their last 22 home games.

27 Amy Moritz, “Toronto Remains a Second Home to Three-Time All-Star Devon White,” Buffalo News, August 10, 2018.

28 Morris Dalla Costa, “White’s catch real Justice,” London Free Press, February 11, 2013.

29 Rutherford.

30 Rutherford.

31 “Free Agent White Jumps to Marlins,” Los Angeles Times, November 22, 1995.

32 Gordon Edes, “Jays’ Carter Has High Praise for White,” South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), March 11, 1996.

33 “Marlins Sign Devon White to Rich Contract,” Lakeland (Florida) Ledger, November 21, 1995.

34 Edes.

35 Jim McLennan, “All-Star Diamondbacks, #1: Are We Not Men? We are Devo!” https://www.azsnakepit.com/2011/7/12/2269502/all-star-diamondbacks-devon-white, accessed February 3, 2022.

36 Ian Thomsen, “3 Los Angeles Dodgers Having Added a Touch of Green, L.A. Believes It Has Chased Away the Blues.” SI Vault, March 27, 2000. https://vault.si.com/vault/2000/03/27/3-los-angeles-dodgers-having-added-a-touch-of-green-la-believes-it-has-chased-away-the-blues, accessed February 13th, 2022.

37 “Dodgers Shopping Sheffield; White Wants Out.” ESPN.com, February 21, 2001. https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/2001/0219/1095073.html,accessed February 13, 2022.

38 Arnie Stapleton (Associated Press), “Dodgers Swap Devon White for Brewers’ Marquis Grissom,” CBC Sports, February 25, 2001. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/baseball/dodgers-swap-devon-white-for-brewers-marquis-grissom-1.257016, accessed February 13, 2022.

39 Stapleton.

40 “Devon White: Seven-time Gold Glove Winner,” Sports Illustrated, January 6, 2017. https://www.si.com/mlb/2017/01/06/hall-fame-one-and-done-devon-white, accessed March 9, 2022.

41 Rutherford, “The Interview, Devon White.”

42 John Lott, “Former Blue Jays Star Devon White Bringing Baserunning Savvy to Buffalo Coaching Gig,” The Athletic, https://theathletic.com/62290/2017/05/24/former-blue-jays-star-devon-white-bringing-baserunning-savvy-to-new-coaching-gig/, accessed February 17, 2022.

43 Lott.

Full Name

Devon Markes White

Born

December 29, 1962 at Kingston, Kingston (Jamaica)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.