Henry Aaron

“Henry Aaron in the second inning walked and scored. He’s sittin’ on 714. Here’s the pitch by Downing. Swinging. There’s a drive into left-center field! That ball is gonna be … outta here! It’s gone! It’s 715! There’s a new home run champion of all time, and it’s Henry Aaron!” — Atlanta Braves’ announcer Milo Hamilton, April 8, 1974

With that swing of the bat, along with the 714 that preceded it, Hank Aaron not only passed Babe Ruth as major-league baseball’s home run leader. He also made a giant leap in the integration of the game and the nation. Aaron, an African American, had broken a record set by the immortal Ruth, and not just any record, but the all-time major-league home run record, and in doing so moved the game and the nation forward on the journey started by Jackie Robinson in 1947. By 1974 Aaron’s baseball career was within three years of sunset, but the road he’d traveled to arrive at that spring evening in Atlanta had hardened and tempered him, perhaps irrevocably, in ways that only suffering can produce. Aaron finally shrugged off the twin burdens of expectation and fear that evening, and few have ever stood taller.

With that swing of the bat, along with the 714 that preceded it, Hank Aaron not only passed Babe Ruth as major-league baseball’s home run leader. He also made a giant leap in the integration of the game and the nation. Aaron, an African American, had broken a record set by the immortal Ruth, and not just any record, but the all-time major-league home run record, and in doing so moved the game and the nation forward on the journey started by Jackie Robinson in 1947. By 1974 Aaron’s baseball career was within three years of sunset, but the road he’d traveled to arrive at that spring evening in Atlanta had hardened and tempered him, perhaps irrevocably, in ways that only suffering can produce. Aaron finally shrugged off the twin burdens of expectation and fear that evening, and few have ever stood taller.

Henry Louis Aaron was born February 5, 1934, in Mobile Alabama, to Herbert and Estella (Pritchett) Aaron.1 Among Henry’s seven siblings was a brother, Tommie, who later played in parts of seven different seasons in the major leagues. For whatever such records are worth, the brothers still hold the record for most career home runs by a pair of siblings, 768, with the elder Henry contributing 755 to Tommie’s 13. They were also the first siblings to appear in a League Championship Series as teammates.

Henry was born in a poorer neighborhood of Mobile called “Down the Bay,” but he spent most of his formative years in the nearby district of Toulminville. Aaron’s father worked at a local shipyard performing manual labor.2 The Aaron family lived on the edge of poverty, in part due to the general economic conditions of the Great Depression, so every member of the family worked to contribute. Young Henry picked potatoes and tended the Aaron garden, and also worked for an ice-delivery truck, among other odd jobs, and while his parents could not afford proper baseball equipment for recreation, Aaron still practiced in endless sandlot games by hitting bottle caps with ordinary broom handles and sticks.3

One of the consequences of this self-coaching was that he developed a cross-handed batting style, a habit he kept until his early days as a professional. In fact, it was not until he was in spring training with the then-Jacksonville Braves that coach Ben Geraghty convinced him to switch hands in his grip. “He came in and was unorthodox as a hitter; he hit cross-handed,” minor league teammate Johnny Goryl said during a 2011 interview. “He went to Jacksonville to play for a Ben Geraghty who got him to hit more conventionally without the cross-handed grip. That’s when his power started surfacing, and the rest was all history.”4 But in high school, Aaron was a gifted athlete and starred in both football and baseball at Central High School for two years. On the diamond he played shortstop, third base, and some outfield on a team that won the Mobile Negro High School Championship during his freshman and sophomore years.

In 1949, the 15-year-old, 140-pound Aaron – inspired by the exploits of Jackie Robinson, whom he’d seen on several exhibition passes through Alabama –tried out with the Brooklyn Dodgers but did not earn a contract offer, likely due to his unorthodox batting grip. Now a high school junior, he transferred to the private Josephine Allen Institute for his final two years of education. The Allen Institute had been founded by Clarence and Josephine Allen in 1895. The Allens were unusually accomplished, educated, and wealthy for Black Americans in that time and place, and their school provided critical education for many children who would have otherwise been denied due to race.

Aaron had been playing for the semipro Pritchett Athletics since age 14, and during those games, and in some of his softball contests, he drew the attention of scout Ed Scott, who convinced Henry and his mother that it would be a good move to sign with the Mobile Black Bears, a semipro team, for $3 a game.5 Estella granted her son permission to play, but only on the condition that he did not travel, thus limiting him to local games.

On November 20, 1951, despite his mother’s concerns about his not continuing on to college, Henry signed for $200 a month with the Negro American League champion Indianapolis Clowns. Scout Bunny Downs had discovered Aaron playing with the Black Bears during an earlier exhibition, and Aaron flourished with Indianapolis, helping guide the team to the 1952 Negro League World Series crown. In 26 games, he posted a .366 batting average, hit five home runs, and stole nine bases. The series, and the season, allowed Aaron to showcase his range of skills not just for regional scouts, but for several major-league organizations as well.

Following the championship, two telegrams reached Henry – one with an offer from the New York Giants, and a second with an offer from the Boston Braves. Aaron chose the latter, evidently because of a $50-a-month difference in salary, and Boston immediately purchased his contract from Indianapolis.6 On June 14, 1952, Aaron signed with Braves scout Dewey Griggs, and reported to the Class-C Eau Claire (Wisconsin) Bears. Despite playing in only 87 games, Aaron batted .336 with 9 homers, 19 doubles, and 61 RBIs, earned a spot on the league’s All-Star squad, and was selected as the Northern League’s Rookie of the Year. As impressive as his on-field performance was, though, it may have even been exceeded by his calm mien both on and off the diamond. The teenager’s demeanor seemed impenetrable to the occasional bigots in the stands, and the clear absence of racial incidents that season proved his maturity in a way that could not be measured by simple interviews. Aaron not only showed the Braves that he was a wonderful prospect on the field, but also that he could handle the inevitable racism with detachment.

The next season found him and Black teammates Horace Garner and Felix Mantilla on the Jacksonville Braves (South Atlantic League). Given Mantilla’s superior ability at shortstop, Aaron moved to second base for the season.7 Along with two other players from the Savannah (Georgia) Indians, Fleming “Buddy” Reedy and Elbert Willis “Al” Isreal, the quintet broke the color line in the South Atlantic or Sally League (or SAL), playing in the heart of old Dixie without the top-cover of a sympathetic national press.8 Aaron, playing second base, almost single-handedly forced the Jacksonville fans to accept him, regardless of race, by leading the entire league with a batting average of .362, and also being the top producer with 115 runs, 208 hits, 36 doubles, 338 total bases, and 135 runs batted in (RBI) title. To cap the first integrated season in SAL history, Aaron led Jacksonville to the title and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.9 Because many parts of the South were still governed by Jim Crow laws, circumstances that forced the Black players to live in separate accommodations and dining on the road, one pundit wrote, “Henry Aaron led the league in everything except hotel accommodations.”10

That year Henry also met a young woman named Barbara Lucas.11 On a lark, she had decided to attend a Jacksonville game one night early in the season, and watched Aaron single, double, and homer. On October 6, 1953, Aaron, not yet 20, and Lucas were married and within a year welcomed their first child, a daughter they named Gaile.

Aaron spent part of the offseason playing winter ball in Puerto Rico, learning to play the outfield and working with coach Mickey Owen on his batting stance, refining his new swing after switching his grip months earlier. On March 11, 1954, in spring training, Henry was penciled into the Braves’ starting lineup as leadoff hitter and right fielder. He homered and singled. Two days later, on March 13, Milwaukee’s left fielder Bobby Thomson severely fractured his right ankle sliding into second base. In the ensuing lineup shuffle, Aaron took his spot as a regular outfielder. The young slugger made the most of his chance.12

The Braves purchased Aaron’s minor-league contract just as spring training ended. On Tuesday afternoon, April 13, 1954, Aaron made his major-league debut in the season opener at Cincinnati, playing left field and batting fifth. Two days later, on April 15, he doubled in the first inning off Cardinals pitcher Vic Raschi for his first major-league hit, and a week later in St. Louis, on April 23, he victimized Raschi again, this time for his first home run. Aaron fractured his left ankle sliding into third base on September 5, ending his season with what would be the only significant injury of his career. Still, in his first 122 big-league games, he batted .280, homered 13 times, and finished fourth in the voting for Rookie of the Year. In 1955 Aaron was moved to right field, and there his league-leading 37 doubles, .314 batting average, and .540 slugging percentage helped him earn the first of 21 consecutive All-Star team slots en route to finishing ninth in NL MVP balloting.

During the early days of his career, Milwaukee’s public relations director Don Davidson began referring to Aaron as “Hank,” not “Henry” as he was known by those close to him, to make the quiet player appear a bit more accessible.

In 1956 Aaron hit .328 to win the first of his two NL batting titles, led the league in doubles (34) and hits (200), and was named The Sporting News NL Player of the Year. He would lead the league four times in doubles and twice in hits. It proved to be mere foreshadowing for the following year.

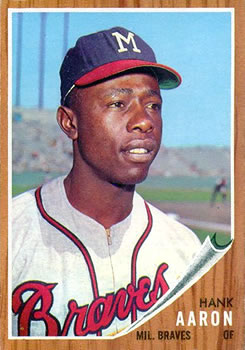

Aaron’s 1957 baseball season began under less-than-ideal circumstances when he missed his train in Mobile and reported one day late to spring training in Bradenton, Florida. Because he had signed a new contract during the offseason, one that raised his salary to $22,500 for the coming campaign, Aaron’s conspicuous tardiness drew the attention of national papers like The Sporting News, as well as the Milwaukee press. The other potential omen came with the distribution of his Topps baseball card. It was printed as a photographic reverse, with Hank appearing to bat left-handed. On closer inspection, his uniform number “44” is reversed, and clearly underscores the mistake, but the Topps corporate leadership chose not to correct the error and reprint the card.

Aaron’s 1957 baseball season began under less-than-ideal circumstances when he missed his train in Mobile and reported one day late to spring training in Bradenton, Florida. Because he had signed a new contract during the offseason, one that raised his salary to $22,500 for the coming campaign, Aaron’s conspicuous tardiness drew the attention of national papers like The Sporting News, as well as the Milwaukee press. The other potential omen came with the distribution of his Topps baseball card. It was printed as a photographic reverse, with Hank appearing to bat left-handed. On closer inspection, his uniform number “44” is reversed, and clearly underscores the mistake, but the Topps corporate leadership chose not to correct the error and reprint the card.

Regardless of what the baseball card showed, Aaron was not affected on the field. Over that March in Florida he batted .390 with 11 home runs, despite missing seven games due to a sprained ankle. Manager Fred Haney, in the March 27 edition of The Sporting News, was quoted: “He [Aaron] hasn’t reached his potential yet. I expect him to do better this year. That’s how we’ve got to improve to win the flag.” Aaron tinkered with his approach in the batter’s box, switching from a 36-ounce bat to a 34-ounce model, and he opened the 1957 season by batting safely, and scoring, in the Braves’ first seven games.

The public praise rolled in during those early weeks. On April 24 Sporting News writer Dick Young noted that Dodgers coach Billy Herman “rates Hank Aaron over Willie Mays as a hitter – and over everyone in the N. L. for my money.”13 The following week, in the same magazine, Bob Wolf wrote: “Whether or not he wins the triple crown, or even two-thirds of it, Aaron certainly must be considered the favorite in the batting derby … and while Aaron isn’t high on his chances of leading the league in homers or runs batted in, he agrees that he should repeat as batting king.”14 After 25 games, Aaron was hitting at a .369 clip and had committed no errors in the field.

Stan Musial, however, was not as impressed as the reporters who followed the team. In a June 26 Sporting News article by Cleon Walfoort, Musial left no room for doubt, stating, “[Aaron] thinks there’s nothing he can’t hit. He’ll have to learn there are some pitches no hitter can afford to go for. He still has something to learn about the strike zone.” His reference to Aaron as an “arrogant hitter” drew a response, cited in the same article, from Pittsburgh manager Bobby Bragan. “Sure, Aaron’s a bad-ball hitter and he always will be, but it would be a bad mistake to try to change him.”15

Given the late arrival to spring training, Musial’s comments, and a general undertone in the wider reporting on Aaron and what was occasionally dismissed as a lack of effort, Haney again came to his slugger’s defense. “That loping gait of Hank Aaron’s is deceptive. You’d almost get the impression he wasn’t hustling at times, but he’d be about the last player you could accuse that of. He just runs as fast as he has to, and you’ll notice he always seems to get to a fly ball or a base in time when there’s any chance of making it.”16

Normally such an offensive outburst would result in a nearly automatic selection to the NL All-Star team, but according to a retrospective article from ESPN, a huge glut of votes from Cincinnati elected Reds to eight National League starting positions. “The lineup was so stacked, in fact, that Commissioner Ford Frick felt he had to intervene, so he replaced outfielders Gus Bell and Wally Post with two guys named Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.”17

The All-Star Game was little more than a brief respite in Aaron’s terrific season. On July 5 he surpassed his 1956 season home run total when he hit number 27 off the Cubs’ Don Elston, which, by mid-month, prompted The Sporting News’ Bob Wolf to begin touting the hitter’s chances for the Triple Crown. Despite his preseason protestation that he did not see himself as a power hitter, after 77 games he was on pace to tie Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, and on August 15 he smacked career homer number 100. One week later he drove in his 100th run of the season. All the numbers, though, paled in comparison to a single swing of the bat the following month.

On September 23, in the bottom of the 11th inning facing St Louis, Aaron stroked a breaking ball over the fence at County Stadium. The two-run shot was the only homer that Cardinals pitcher Billy Muffett surrendered all year, but the walk-off win clinched the NL pennant for the Braves. Aaron was carried off the field that night by his jubilant teammates, and he always remembered that hit, that game, and that night as one of the greatest moments of his career.

In a February 26, 2012, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel retrospective, baseball commissioner Bud Selig was quoted: “Henry Aaron in ’57 was, well, he was a player for the ages. I have never seen a hitter like him. Forget our relationship. I’m telling you in the ’50s, when you watched Hank Aaron, you knew you were watching something really special.”18 That year, Aaron led the NL with 44 home runs, 132 runs batted in, 369 total bases, and 118 runs scored, but failed to meet his batting goal of .350. Instead, he finished a “mere” fourth in the league race with a .322 average. It was enough to earn him the only Most Valuable Player trophy of his career.

He followed that with 11 hits, including three homers, in 28 at-bats in the World Series. His .393 average certainly contributed to the Braves’ world championship, and was a fitting conclusion to a remarkable season. Both the man and his team walked off the field after the final out that October as, unquestionably, the best in baseball.

The year 1957 was also special for the Aarons for other reasons. In March, Barbara had delivered their first son, Hank Jr., and in December twins Lary and Gary arrived. Tragically, Gary died in the hospital, but the family carried on. It would grow once more, in 1962, with the birth of youngest daughter Dorinda.

In 1958, due in large part to Aaron’s 30 home runs, the Braves returned to the World Series, but lost to the Yankees in seven games. Although Henry Aaron only finished third in MVP voting for the year, he did win his first Gold Glove award. The following year the rising star appeared on the television show Home Run Derby, and won six consecutive matches – along with $13, 000 – before falling to the Phillies’ Wally Post. Afterward, Aaron noted that he changed his swing to help him hit more home runs because “ … they never had a show called ‘Singles Derby.’”19

His 1959 season was, arguably, the best of Aaron’s extraordinary career. Not only did he lead both major leagues in hits (223), batting average (.355), slugging (.636), and total bases (400), he committed only five errors all season while winning his second of three Gold Glove awards. The fielding mark is even more impressive in that, although he played 144 games as right fielder, he also played 13 in center and even five full games in the infield, at third base.

Aaron hit his 200th career home run on July 3, 1960, off Cardinals pitcher Ron Kline, and on June 8, 1961, he joined Eddie Mathews, Joe Adcock, and Frank Thomas as the first quartet to hit successive homers in a single game, a 10-8 loss to the Cincinnati Reds. In 1963 he led the NL in home runs and RBIs, and also became the third-ever member of the 30/30 club, stealing 31 bases and socking 44 homers. That year Aaron barely missed winning the Triple Crown, losing the batting title to Tommy Davis by a scant .007 points, finishing in a tie with Dick Groat for fourth place in the major leagues with a .319 batting average.

He continued to excel throughout the decade. In the mid 1960s, though, the Braves uprooted the team and moved to Atlanta, as far south as any team in the major-league game. From a 2014 interview by Aaron, published in the Atlanta Business Chronicle, he “was not upset that his team would be moving to the segregated South. Aaron, who had grown up in Mobile, Alabama, played for the Jacksonville Braves and had traveled throughout the South when he was in the minor leagues. “It was something I had to get used to … I’m going to be playing baseball.

Coming up through the minor league system, I had always been affiliated with the Braves,” Aaron said. Because he cared about playing baseball, it didn’t matter if he was in Milwaukee or Atlanta. “I don’t have to be associated with anybody but the baseball players.”20

In 1966, the first season for the Braves in Georgia, Aaron hit his 400th career home run off Bo Belinsky in Philadelphia, and crested the 500-plateau two years later, in 1968 against Mike McCormick and the San Francisco Giants. He moved into third place on the all-time career home run list on July 30, 1969, when he passed Mickey Mantle with number 537. Despite his personal successes, and another third-place finish in the MVP race, the Braves were swept in three games by the improbable New York Mets in the new League Championship series. In the inaugural NLCS, Aaron batted .357 with three home runs.

The 1960s marked the peak of Aaron’s career. From 1960 to 1971, he averaged 152 games per season. In an “average” season, Aaron batted .308, scored 107 runs, amassed 331 total bases, hit 38 homers, and drove in 112 runs. This was all the more remarkable in that the time frame is widely remembered as the “decade of the pitcher,” yet Aaron gave no quarter when batting against some of the best in the game. Don Drysdale was his most frequent career home run victim, yielding 17, but the slugger also punished luminaries like Sandy Koufax and Juan Marichal, along with a wide array of less-gifted hurlers.

His gift in the batter’s box flowed through his hands and wrists. In the 1990 book Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball, author George Will summarized Hank’s approach: “Henry Aaron once said, ‘I never worried about the fastball. They couldn’t throw it past me. None of them.’ That was true, but that was Aaron, he of the phenomenally quick wrists and whippy, thin-handled bat.”21 Despite standing six feet tall, Aaron weighed a mere 180 pounds, almost scrawny in comparison to later sluggers, but his unique physical talent allowed him to wait on the pitcher for a split second longer than most other hitters, to seemingly pluck the ball from the catcher’s glove with his bat, and made him one of the most feared sluggers in the league.

With his 3000th career hit, a single against the Cincinnati Reds on May 17, 1970, Henry Aaron became the first player ever to reach the dual milestones of 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. That year, with his 38 homers, he established a new NL record for most seasons by a player with 30 or more home runs. The following year, on April 28, Aaron hit homer number 600 off future Hall of Fame pitcher Gaylord Perry, joining Ruth and Mays in a most exclusive power-hitting fraternity. With his career-high 47 home runs that year he also set a new league record for most seasons with 40 or more homers with seven, and set an unofficial mark for “close-but-no-cigar” when he finished third in MVP balloting for a sixth time.

On the personal front, things between Henry and Barbara came to a head. The couple had been having marital difficulties since 1966, and had drifted apart. In February 1971, they formalized the separation with a legal divorce. Two years later, in 1973, Aaron married Billye Williams, a former Atlanta television journalist, in Jamaica.

Despite major-league baseball’s first labor-related work stoppage in 1972, Aaron passed Mays on the all-time home run list when he hammered number 661 off Reds pitcher Don Gullett on August 6. The impact of the strike wouldn’t really show until the following season. The two weeks that were lost to pension benefit negotiations represented eight lost opportunities for Aaron to continue his chase of Ruth’s career home run record, and by the end of 1973, with the national media working itself into a lather over Aaron’s pursuit of the iconic total, he ended the season with 713, one shy of tying the Bambino.

The stresses on the player, the team, opposing pitchers, and the sport that were spawned – or perhaps revealed – by Aaron’s 1973 season have been chronicled in a variety of sources. He retained an essential quiet dignity with the media and never allowed the moment to cause him to break in public, although a lesser man certainly might have cracked. Aaron received, literally, thousands of letters every week, and the torment prolonged over the winter of 1973 due to the strike in 1972. In 1973, however, the nation was a scant decade past the passage of the contentious Civil Rights Act, and less than a generation since Rosa Parks had refused to move to the back of her bus, so overt bigotry was not nearly as foreign as it might be now. Some of the letters that Aaron opened, however, are almost unbelievable for any era.

Some of the notable ones from the collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown (spelling is verbatim):

“Hi, Hank,

I sees you hit 711 homers. When I goes to sleep every night I pray as follows:

1 – That you’se stop hitting these cheap homers

2 – That the pitchers stop lobbing in the ball for you to hit.

3 – That youse have a good accident when youse hit 713 and never been able to play another game.

4 – That youse get good and sick.

5 – That Babe Ruth is the best homer hitter & 714 is always the record.

6 – That youse get mugged by one of our brothers of the Black Panther Party.”

Another one, from mid-1973, read:

“Dear Hank Aaron,

Why are they making such a big fuss about your hitting 701 home runs.? sic

Please remember, you have been at bat over 2700 more times than Babe Ruth. If Babe Ruth was at bat 2700 more times he would have hit 814 home runs.

So, Hank what are you bragging about. Lets have the truth. You mentioned if you were white they would give you more credit. That’s ignorance. Stupid.

Hank, there are three things you can’t give a Nigger. A black eye, a puffed lip or a job.

The Cubs stink, the Cubs stink, Hinky Dinky, Stinky Parlevous. The Cubs are through, the Cubs are through, Hinky Pinky Parlevous.”

These are just a tiny sample of the venom and rage directed at Aaron throughout the later stages of his quest. In a third letter, a self-described “50 year old White Woman from Massachusetts” wrote, “To Hank Aaron: A Rotten Nigger … .you must have made every intelligent white man hate you and your opinions even more … ”.22 Describing those letters as mere irrational raving is reasonable nearly 40 years after the chase, but at the time, with a Black player pursuing the record of a White one, the threats seemed very real.

On the positive side, once the nation became aware of the bigotry, public support for Aaron poured in. But Aaron, perhaps channeling his inner Jackie Robinson, took the field without apparent regard for the attention surrounding his play. Atlanta opened the 1974 season in Cincinnati, and although the Braves management wanted Hank Aaron to break Ruth’s record in Atlanta, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn decreed that Aaron had to play at least two of the thee-game road series.

Aaron sat on his 713 total for one at-bat, hitting number 714 on April 4 off Cincinnati’s Jack Billingham. On April 8, in front of 53,775 fans in Atlanta, Aaron finally broke the record with a fourth-inning shot off the Dodgers’ Al Downing. Dodgers radio announcer Vin Scully captured the moment: “What a marvelous moment for baseball; what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron. … And for the first time in a long time, that poker face in Aaron shows the tremendous strain and relief of what it must have been like to live with for the past several months.”23

The euphoria lasted all season, until October 2, when Aaron hammered his 733rd, and final, homer in Atlanta for the Braves. One month later, on November 2, Atlanta traded the all-time home run king to the Milwaukee Brewers for minor-league pitcher Roger Alexander and outfielder Dave May. “When Bud Selig called me,” [Aaron, talking about the trade] said to the New York Times. “I was too sleepy to get all the details … All I know is that I’m happy to be going back home. This is the first time I’ve ever been traded. If I was being traded to a city like Chicago or Philadelphia, I’d frown on it. But I’m going back to Milwaukee … I’m going back home.”24

Hank Aaron became a “designated hitter.” The next season, on May 1, 1975, Aaron became the all-time RBI leader, and on July 20, 1976, he hit the 755th home run of his career in Milwaukee’s County Stadium. He appeared in his final major-league game on October 3, calling it a career after 3,298 games.

In that career, Aaron scored 2,174 runs, and is the all-time leader in RBIs (2,297), total bases (6,856), and extra-base hits (1,477). The total bases figure is ‘just another stat’ at first blush, but Aaron’s lead over Albert Pujols, #2 on the list, is 645, or almost 10%. It is one of Aaron’s most remarkable displays of dominance across all eras. His 12,364 at-bats remain the second highest total ever, and he is on many of Major League Baseball’s “top ten” lists, including doubles, plate appearances, and hits (3,771). Even more remarkable is that he remains on these lists more than 35 years since he last took the field. In his otherwise hilarious and irreverent book Catcher in the Wry, former Aaron teammate and longtime Brewers’ broadcaster Bob Uecker is quite serious when he observes that, “[Aaron] was the most underrated player of my time, and his.” This period included tremendous players like Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, and Roberto Clemente, yet Aaron did more for less recognition than anyone else. Uecker continued, “I asked him once if he felt slighted. He said, ‘What difference does it make?’”25

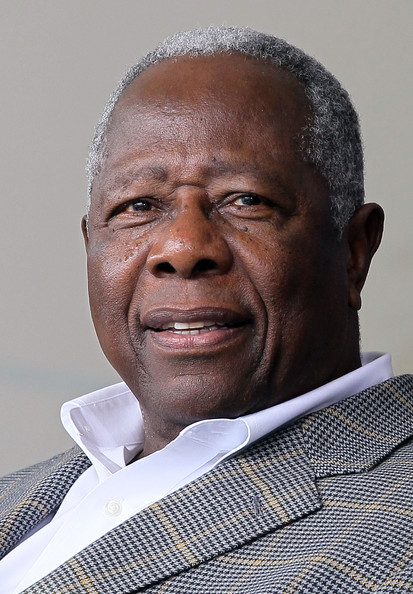

After retiring, Aaron returned to Atlanta as vice president of player development for the Braves, and on August 1, 1982, was formally inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, although an inexplicable 2.2 percent of the ballots did not contain his name. He also worked for a time for Turner Broadcasting, and opened Hank Aaron BMW in Atlanta. His auto empire eventually grew to multiple dealerships in Georgia, although he sold all but one in 2007, and he expanded his business venture to include a number of smaller restaurants as well. The 755 Restaurant Corporation grew to 18 fast-food venues in the Southeast, including several Church’s Fried Chicken outlets.

After retiring, Aaron returned to Atlanta as vice president of player development for the Braves, and on August 1, 1982, was formally inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, although an inexplicable 2.2 percent of the ballots did not contain his name. He also worked for a time for Turner Broadcasting, and opened Hank Aaron BMW in Atlanta. His auto empire eventually grew to multiple dealerships in Georgia, although he sold all but one in 2007, and he expanded his business venture to include a number of smaller restaurants as well. The 755 Restaurant Corporation grew to 18 fast-food venues in the Southeast, including several Church’s Fried Chicken outlets.

It was not a simple, happy ending. In 1984, brother Tommie passed away due to leukemia. Older brother Hank later said in an interview: “I was sitting in my office one day in 1982,” Aaron wrote later wrote, “when my brother Tommie walked in and told me that he had some kind of blood disorder … the whole time, Tommie never demonstrated any pain until the very last night before he passed … It was the hardest night of my life.”26

In 1990 he wrote his autobiography, I Had a Hammer, and in April 1997 the Mobile Bay Bears (Southern League) christened “Hank Aaron Stadium” in Mobile. In 1999 Major League Baseball created the Hank Aaron Award to be awarded to the best offensive performers in each league each season, and in 2000 Aaron was named to MLB’s All-Century Team. In 2001, he was awarded the Presidential Citizen’s Medal by President Bill Clinton, and in 2002 was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush.

That slew of awards underscores Aaron’s fame and his relevance not only to baseball’s past, but also to America’s history. He was a Black man who successfully challenged the record of a White player whose legacy borders on mythical, and he did so with a poise so unshakable that it remains a study in professionalism. Naturally taciturn in public, he was only rarely able to convey his inner feelings with words, but he reserved one of his finest moments for the end of another controversy-laden home run chase, by Barry Bonds in 2007. When Bonds finally hit his 756th homer, Aaron’s face appeared on the JumboTron scoreboard in San Francisco, and he relayed a message to his replacement:

“I would like to offer my congratulations to Barry Bonds on becoming baseball’s career home run leader. It is a great accomplishment which required skill, longevity, and determination. Throughout the past century, the home run has held a special place in baseball and I have been privileged to hold this record for 33 of those years. I move over now and offer my best wishes to Barry and his family on this historical achievement. My hope today, as it was on that April evening in 1974, is that the achievement of this record will inspire others to chase their own dreams.”

Henry Aaron passed away in his sleep on January 22, 2021, just two weeks shy of his 87th birthday.27 He is buried at South View Cemetery in Atlanta.28

Dignity. Pride. Courage. Those are words often reserved for describing heroes. They also describe Henry Aaron.

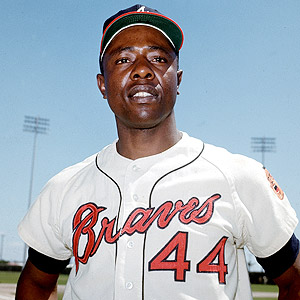

Photo credits

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Trading Card Database, Atlanta Braves.

Notes

1 “Henry Aaron,” Alabama, U.S., Surname Files Expanded, 1702-1981; Alabama Department of Archives and History, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61266/images/41904_539897-00023?pId=61280

2 Bill James, “Henry Aaron,” The Baseball Book: 1990 (New York: Villard, 1990), 161.

3 Hank Aaron and Lonnie Wheeler, I Had A Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story (New York, Harper Perennial, 1991), 14.

4 Nick Diunte, “Hank Aaron’s Lone Season in Puerto Rico Forever Altered His Path to the Hall of Fame,” Forbes.com, January 22, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickdiunte/2021/01/22/hank-aarons-lone-season-in-puerto-rico-forever-altered-his-path-to-the-hall-of-fame/

5 Aaron and Wheeler, 32.

6 Aaron and Wheeler, 53.

7 James, 161.

8 Isreal’s last name is often spelled “Israel” – like the nation, but Baseball-Reference.com uses “Isreal”. https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=isreal001elb. Of note, however, is that his father Frank’s World War II draft card spells the name (and in the signature), “Israel”.

9 “Henry Aaron, Negro Athlete, Is Voted Sally’s Most Valuable,” Panama City News Herald, August 19, 1953: 5.

10 Larry Schwartz, “Hank Aaron: Hammerin’ Back at Racism,” ESPN.com, accessed September 20, 2024, http://espn.go.com/sportscentury/features/00006764.html

11 Howard Bryant. The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron (New York: Random House, 2010), 56.

12 Bryant, 69.

13 Dick Young, “Clubhouse Confidential,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1957: 17.

14 Dick Young, “Aaron Whipping Up Plate Breeze Aided By Lighter Bludgeon,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1957: 11.

15 Cleon Walfoort. “Aaron Turns Bad Pitches Into Base-hits,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1957: 7.

16 Walfoort, 7.

17 Steve Wulf, “The stuff of legends: In 1957, Cincinnati fans stacked the All-Star team too,” ESPN.com, June 29, 2015, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/13168334/1957-cincinnati-fans-stacked-all-star-team-too

18 Gary D’Amato, “Seasons of Greatness: No. 2 Hank Aaron 1957,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 26, 2012, http://m.jsonline.com/more/sports/brewers/140517023.htm

19 “Images from Hank Aaron’s chase for the career home run record,” ESPN.com, January 22, 2021, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/30759553/images-hank-aaron-chase-career-home-run-record

20 Maria Saporta, “Hank Aaron reflects on past 50 years in Atlanta; Braves move to Cobb,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, October 24, 2014, https://saportareport.com/hank-aaron-reflects-on-past-50-years-in-atlanta-braves-move-to-cobb/sections/abcarticles/maria_saporta/

21 George Will, Men At Work: The Craft of Baseball (New York: MacMillan, 1990), 206.

22 Archives, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York (visited: 2011).

23 Jon Paul Hoornstra, “Relive Hank Aaron’s 715th Homer Through Vin Scully’s Historic Call,” Newsweek.com, accessed September 20, 2024, https://www.msn.com/en-us/sports/other/relive-hank-aaron-s-715th-homer-through-vin-scully-s-historic-call/ar-BB1lioQU

24 Alex Coffey, “The Braves Trade Hank Aaron to the Brewers,” BaseballHall.org, accessed September 20, 2024, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/inside-pitch/the-braves-trade-henry-aaron

25 Bob Uecker and Mickey Herskowitz, Catcher in the Wry (New York: Berkeley Publishing Group, 1982), 167-168.

26 Aaron and Wheeler. I Had a Hammer; 434.

27 Richard Goldstein, “Hank Aaron, Home Run King Who Defied Racism, Dies at 86,” New York Times, January 22, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/sports/baseball/hank-aaron-dead.html

Full Name

Henry Louis Aaron

Born

February 5, 1934 at Mobile, AL (USA)

Died

January 22, 2021 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.