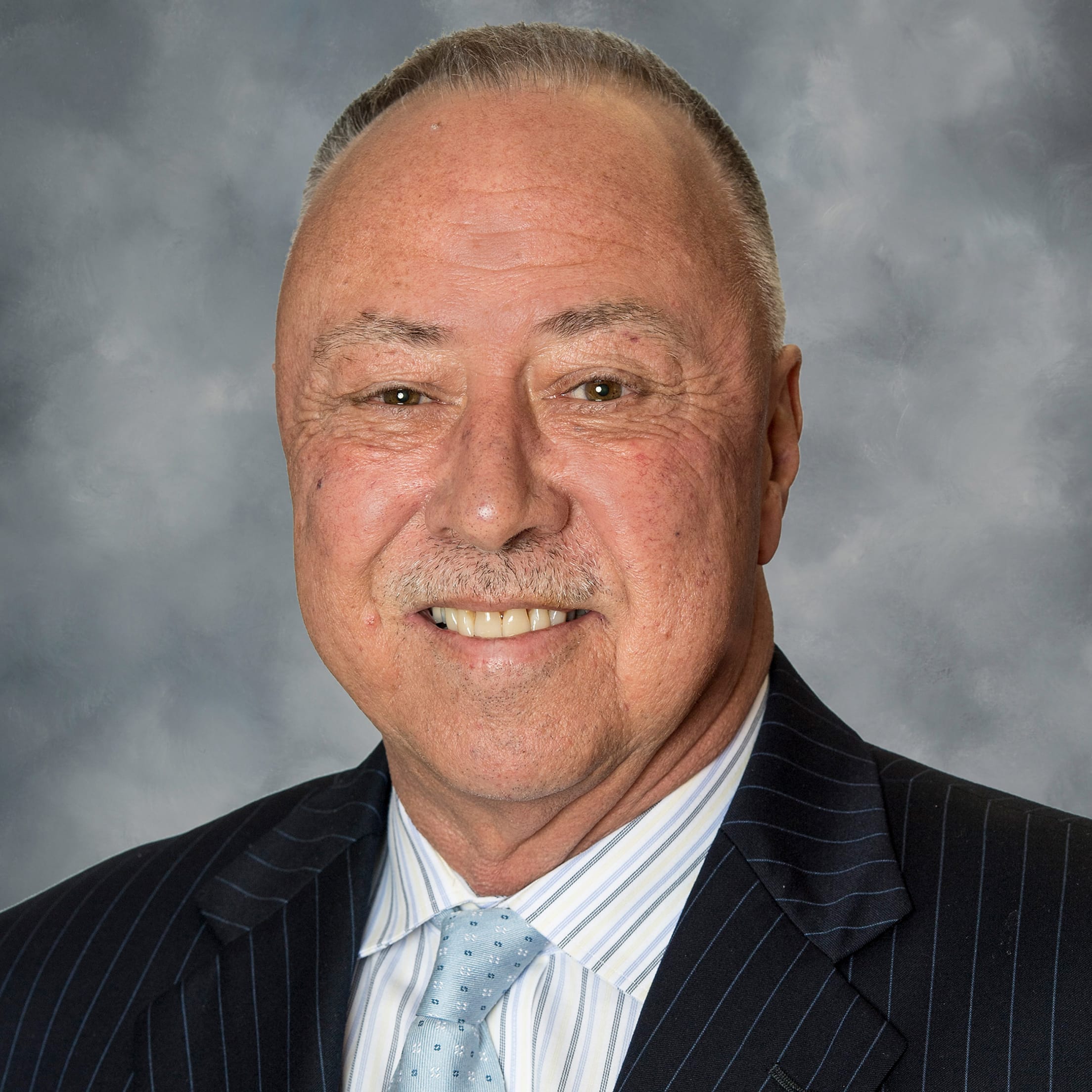

Jerry Remy

For 34 years TV broadcaster Jerry Remy was a familiar presence in the living rooms of Red Sox Nation. Genial and relaxed, Remy (rhymes with “hemi”) conveyed his professional expertise without arrogance – the ideal companion for watching baseball. As team chairman Tom Werner described him, “He’s the guy you’d like to have a beer with after the game.”1 His apparent friendliness endeared him to fans. Don Orsillo, one of his partners in the booth, said, “People feel like they know him and that he is part of their family, even if they have never met.”2

For 34 years TV broadcaster Jerry Remy was a familiar presence in the living rooms of Red Sox Nation. Genial and relaxed, Remy (rhymes with “hemi”) conveyed his professional expertise without arrogance – the ideal companion for watching baseball. As team chairman Tom Werner described him, “He’s the guy you’d like to have a beer with after the game.”1 His apparent friendliness endeared him to fans. Don Orsillo, one of his partners in the booth, said, “People feel like they know him and that he is part of their family, even if they have never met.”2

The real Remy was different. “I don’t think I could be any more opposite than what I am on the air,” he once said.3 He was introverted, with an anxious edge. He called himself a “real recluse,” saying he was “extremely uncomfortable in social situations of any kind.”4 Another TV partner, Sean McDonough, described Remy as “socially awkward … he is not comfortable around people he does not know.”5

What Red Sox fans saw on TV was his public image, built over time with the help of his colleagues in the broadcast booth who relieved his anxiety and brought out his humor. The jocularity that charmed TV audiences did not reflect Remy’s normal personality. His wife Phoebe confirmed this, saying that when fans would tell her, “He’s so funny! You must laugh all the time,” she would just smile.6

Ultimately many of his private struggles became public. His son Jared committed a horrific murder and in the ensuing media firestorm, some questioned if the Remys could have done more to prevent it. Late in his life, dealing with lung cancer, Remy came out and admitted his own mental-health challenges. Still, through all these revelations, he remained much beloved by Boston fans. When he died at age 68, they grieved for him as one of their own.

Gerald Peter Remy was born in Fall River, Massachusetts on November 8, 1952, and grew up in Somerset, a town close to the Rhode Island border. He was three-quarters French Canadian and one-quarter Irish, representing two of the four largest ethnic groups in Massachusetts.7 His father Joe was a salesman at Mason’s Furniture and his mother Connie was a hairdresser and a dance instructor.8 At an early age, young Jerry felt that his shyness set him apart from the rest of his family. He remembered his parents as positive and outgoing, and described his sister Judy as “the complete opposite of me – happy-go-lucky, friendly.”9

He found an outlet in physical activity. Their house was beside a park where he excelled at sports year-round: baseball, basketball, and in the winter, hockey on the frozen pond. While he was on the small side, he was “fast as a horse.”10 He attributed this to the dance training his mother got him into. “I was a tap dancer until I was 14 years old … I really believe that dancing is the reason I had quick feet. … It’s what gave me my quickness, my speed.”11

His father and his grandfather, who lived nearby, were devoted Red Sox fans. He said of his father, “His love for Ted Williams was off the charts.”12 Remy was about nine when his family first took him to Fenway. “I remember walking up to that runway between home plate and first base and the first thing that hit me was the Monster and the color, that green color. It was just amazing.”13

In Little League he starred as a shortstop, copying the batting stance of his hero, Carl Yastrzemski. “My life was playing baseball and, later as a teenager, spending time with my friends, smoking Marlboros and drinking Buds,” he recalled.14 “We raised some hell. How we didn’t end up in jail at times, I don’t know.”15

At age 16 Remy played in an annual youth all-star game at Fenway Park.16 That may have been where he caught the eye of a local scout. In June 1970 he was drafted by the Washington Senators in the 19th round.17 He decided to try college instead, following a friend to St. Leo’s in Florida, but the coach said he was academically ineligible to play. He went home and enrolled at Roger Williams College in Rhode Island, completing one semester. In January 1971 he was picked by the Angels in the eighth round of the secondary draft. Scout Dick Winseck signed him for $500 a month. Remy had never met Winseck before nor seen him at a game. “I always had the feeling I was one of those leftover players,” he said.18

In spring training, he competed against guys with far more experience. Remy felt outclassed. He said to himself, “What the hell am I doing here? I don’t belong here.”19

He was sent to play “short season” ball in Holtville, California. Much later he heard that minor-league management considered cutting him, but Kenny Myers, an “old crusty baseball guy,” stood up for him, saying, “If he can run, I can teach him how to play.” Myers had done this before with Willie Davis. Remy later said that Myers was “the only reason that my professional baseball career continued.”20

Myers put Remy through a grueling regimen. “If we had a 7:00 PM game he had me out there at 10:00 in the morning … working on everything. He was tough but he was a great teacher.”21

Remy was optioned to a team in Twin Falls, Idaho made up of other optioned players. While he batted .308 in 32 games, he realized, “I was way off everybody’s radar screen.” Discouraged, he considered quitting, but his father convinced him to persevere.22

He spent the 1972 season with the Class-A Stockton Ports of the California League. He hit .265, but struck out 100 times in 579 plate appearances. In 1973, playing A-ball in Davenport, Iowa with the Quad Cities Angels of the Midwest League, he improved his hitting and fielding. His .335 average led the league for batters with at least 400 plate appearances.23

In 1974 he ascended to Double-A El Paso, where he led the Texas League in batting (400 PA minimum), this time with a .338 average. Manager Dave Garcia helped him develop his throwing arm and told him, “You’re going to be a big leaguer.” For the first time, Remy began to feel good about his prospects.24 He was called up to Triple A for the last six weeks of the season, playing at Salt Lake City under manager Norm Sherry. Remy hit .323 combined that year.

The next step was winter ball in Mexico with Dave Garcia as manager of the Yaquis de Obregón, in Ciudad Obregón, Sonora. Remy was a 22-year-old newlywed, having just married 20-year-old Phoebe Brum, from a Portuguese family in Fall River.25 The young couple suffered culture shock in Mexico. The often-violent fans made Remy nervous, and his new wife was sick the whole time.26 But the team made the playoffs.

After spring training in 1975, Remy joined the big club. His first game in the majors was on April 7, in Anaheim, against the Kansas City Royals. In his first big-league at-bat, Remy hit a second-inning single to left field off of Steve Busby, driving in one run and sending another runner to third. In the pregame meeting, one of the coaches had warned about Busby, “If there are runners on first and third, look out, because he fakes to third and throws to first, and he’s good at it.”27 In all the excitement, Remy forgot this advice and Busby used that move to pick him off first base.

Manager Dick Williams took him aside in the dugout and told him that if it happened again, “your ass is going to be back in Salt Lake City quicker than you can snap your fingers.”28 Remy recalled that “the next time I was on base with a runner on third, I took a lead of about six inches.”29 He ended his rookie year hitting .258 and stealing 34 bases, although he led the league by getting caught stealing 21 times.

Williams was fired 96 games into Remy’s second year. Even so, Remy remembered, “Dick Williams taught me more in one year than any other manager I ever played for.”30

Norm Sherry, Remy’s manager in Salt Lake City, replaced Williams. Sherry made the surprising decision to name Remy team captain. He told a writer, “I know he’s young, but he plays hard, and he has his teammates’ respect in that he’s not afraid to speak out, to assert himself.”31 As a player, Remy was grimly competitive. In later years, he said that he “just couldn’t leave the game at the ballpark”32 and admitted that he was a perfectionist.33 Referring to hotheaded Boston shortstop Rick Burleson, known as “Rooster,” Remy said, “We had an awful lot in common … Nobody got pissed off quicker than Rooster did. I might have been second in that category.”34 It was likely that Sherry saw this fiery quality in him and thought he might be the sparkplug the Angels needed. Remy batted .263 and stole 35 bases in 1976 as the Angels finished fourth in the AL West.

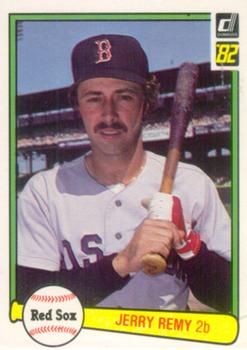

“I thought our attitude was improving as a team,” Remy said later.35 A better attitude wasn’t enough. In 1977 the Angels finished fifth, leading to Sherry’s firing. During the winter meetings, the team traded Remy to Boston for pitcher Don Aase and cash. “[Boston] needed speed,” he recalled. “And I had that.”36 The Red Sox were well-stocked with hitters, but they were looking for a leadoff man who could steal bases, and Remy was a good fit. And he wanted nothing more than to play for the Red Sox.

The 1978 season began with great promise, as the Red Sox streaked to a 51-21 start and looked unstoppable.37 Remy also had a good start and was selected for the All-Star Game, though he did not play. But on July 9, Burleson strained ligaments sliding into second38. With the Rooster out, the team lost 14 of their next 22 games. Meanwhile the Yankees went 13-9, cutting the Red Sox lead from 11 1/2 games to 6 1/2.

The 1978 season began with great promise, as the Red Sox streaked to a 51-21 start and looked unstoppable.37 Remy also had a good start and was selected for the All-Star Game, though he did not play. But on July 9, Burleson strained ligaments sliding into second38. With the Rooster out, the team lost 14 of their next 22 games. Meanwhile the Yankees went 13-9, cutting the Red Sox lead from 11 1/2 games to 6 1/2.

On July 24, amid festering turmoil with owner George Steinbrenner and Reggie Jackson, Yankees manager Billy Martin ragequit. Bob Lemon, recently fired as White Sox manager, took over. From then through September 6, the Yankees continued their surge, going 30-13. They climbed from third to second place and cut the Red Sox lead to four games.

The two teams met in a series September 7-10 at Fenway. The Red Sox made 12 errors and lost all four games in an epic disaster that came to be known as the “Boston Massacre.” Boston fell out of first place on September 13, but battled back to tie the Yankees on the last day of the season, at 99-63.

There was a one-game playoff on October 2. Bucky Dent’s three-run homer off Mike Torrez in the seventh inning gave the Yankees a 3-2 lead, but in the bottom of the eighth, down 5-2, Remy doubled off reliever Goose Gossage and scored Boston’s third run. He faced Gossage again in the ninth with one out and Boston trailing, 5-4. Burleson was on first, having walked. Remy singled to right and for a moment it looked like right fielder Lou Piniella might misjudge the ball. Third-base coach Eddie Yost called for Burleson to go from first to third, but the Rooster stopped at second. Remy recalled, “I’d have had a statue out at Fenway if that ball had … got by Piniella because there was an outside chance I could have had an inside-the-park home run, and we would have won.”39 Jim Rice’s flyball moved Burleson to third. But Gossage got Yaz to pop out to end the game and Boston’s pennant hopes.

With those two hits, Remy concluded the season batting .278. He stole 30 bases, making him the first player in American League history to have at least 30 steals in each of his first four seasons.40

On July 1, 1979, at Yankee Stadium, Remy led off the game with a triple off Catfish Hunter. He tried to score on a pop-up by Burleson but was out by about 10 feet. “As I went in to slide, my spike got caught. My body went one way, my knee went in an opposite direction.”41 Jim Rice scooped him up “like I was a child,” Remy remembered.42 He missed most of the rest of the year due to damaged ligaments in his left knee. The Red Sox finished in third place.43

Remy was having an excellent year in 1980, batting .313 with 14 stolen bases going into the All-Star break. Then in the first game back, in Milwaukee on July 10, he reinjured the knee. He had to have surgery to repair torn cartilage,44 ending his season. That was the first of several knee surgeries he would undergo in the coming years.

Remy participated in Red Sox history on September 3, 1981, when he played against the Mariners in a 20-inning game, the longest ever at Fenway. He had six hits in 10 at-bats before the game was suspended due to a 1 A.M. curfew. Boston ended up losing 8-7 when play resumed the next day.45

He became a free agent and in December, after protracted negotiations with the Red Sox, he signed a five-year contract for $2.8 million. This was a big relief for Remy. “It may sound corny, but my heart belongs here,” he said, and expressed his desire to stay with the organization after his playing career was over.46

Remy stayed healthy in 1982. “All he wants to do is go out and play the game,” manager Ralph Houk said. “He does everything we want him to do, does it quietly, and is a big key to our club.”47 He played in 155 games, a career high, and batted .280. The following year, despite a slow start at the plate due to a back injury in spring training, he finished with a .275 average. But in early May of 1984, in a game against the White Sox, he aggravated his knee injury and was soon lost for the season. Remy played in only 30 games, hitting .250. He had surgery in June and again in the fall.48

The spring of 1985 brought bad news: Remy’s knee was even worse than it was before surgery. He did not play at all that year. In November, after the seventh procedure on his knee, he was put on waivers by GM Lou Gorman and promised a shot at making the team in the spring.49 But after his first exhibition game in spring training of 1986, he knew he could no longer compete. He retired in April.50

In 10 years in the majors, Remy batted .275 with seven home runs, 329 RBIs, and 208 stolen bases. Bill James, in his 2002 Historical Abstract, named Remy as the 100th best second baseman of all time. “I can never say I relaxed playing baseball in my whole career,” Remy said.51 “I never felt comfortable. Even when I was doing well, I was always expecting the next shoe to drop and blow everything up.”52

With one year left on his contract, Remy agreed to serve as a coach for Double-A New Britain in 1986. He wanted to get into managing, so in 1987 he sought the Pawtucket job, but the Sox stayed with the incumbent, Ed Nottle.53 Remy took that year off.

In 1988 he interviewed with the New England Sports Network (NESN). They were seeking a partner for longtime broadcaster Ned Martin. It came down to a choice between Remy and Mike Andrews. Remy got the job and Andrews became the executive director of the Jimmy Fund. “I think what helped me was the fact that I was current, and I was from New England. The drawback was that I had absolutely no TV experience,”54 Remy said. “I didn’t think it would be that difficult and then all of a sudden, we were live, and I was like, holy shit, I don’t know what I’m doing. I didn’t know how many outs there were, I didn’t know what the score was. It was horrible.”55

By his own estimation, Remy took “a couple of years” to learn the ins and outs of being a TV analyst.56 Martin, who had been calling Red Sox games on radio and TV since 1961, was a strong supporter. His calmness helped Remy during those difficult early years. In Remy’s view, “I think it would’ve ended differently had it been someone else.”57

During Remy’s playing days, Sox fans from Massachusetts admired him for being a “local boy made good.” Now they enjoyed hearing his familiar broad accent (some would say closer to Rhode Island than Boston). The word “umpire” became “Um-pie-yah.” He referred to young Boston pitcher Dana Kiecker as “Daner Kickah” and transmogrified the name of Cleveland’s Carlos Baerga into “Caaahlos Bahyayger.” This became a running gag over the years.58

NESN fired Martin in 1992 and replaced him with Bob Kurtz.59 In 1996 the Red Sox and their TV stations decided that Remy would be the analyst for all the games.60 This paired him with Sean McDonough, the son of veteran Boston sportswriter Will McDonough. Remy characterized him as “absolutely brilliant, with a photographic memory.”61 McDonough used his lively wit to tease Remy, trying to coax him out of his shell. His goal was to make Jerry laugh so hard that he would take his headset off.62 Remy credited McDonough with helping him open up: “What he did for me was challenge me and bring out my personality.”63

Some viewers did not enjoy their lighthearted interactions. McDonough remembered a letter from an angry woman who wanted them to “stick to the game” and stop drifting off into “inane banter.”64 The TV crew played along, flashing an “Inane Banter Warning” graphic in the corner of the screen. But most fans were delighted with it, and Remy’s popularity grew.

Remy had experienced mood swings throughout his playing days but always disregarded them. “I’d have these days when I’d wake up pissed for no reason at all,” he said. “I’d take it out on everybody.” Then it would suddenly go away until it recurred again the next month.65 However, in 1997 his anxiety and depression abruptly spiraled out of control. On July 18, in Cleveland, he thought he was having a heart attack. The Cleveland team doctor determined that it was probably a panic attack. The episodes continued and got worse. “I got really claustrophobic. I was afraid to drive.”66 Therapy was ineffective.67 Finally Remy got the panic attacks under control with medications.

“I was always an anxious person, but to develop panic attacks and to have that sudden depression was stunning to me,” Remy wrote in his 2019 book. He attributed his mental-health crisis to the pressures of broadcasting for a full season and to “stress from issues at home.”68 What Remy did not mention in his book was that these “issues at home” included a cascade of increasingly urgent problems with his eldest son, Jared. Learning disabilities and aggressive behavior caused the Remys to transfer the teenager from the Weston public high school to the Gifford School, “a therapeutic day school for students with complex social, emotional, and learning challenges.”69 During the 1995-96 school year, the 17-year-old’s unacceptable conduct escalated and he was asked to leave Gifford.70 Police were called when Jared harassed an ex-girlfriend and her new boyfriend. To further complicate matters, Jared’s 15-year-old girlfriend, Tiffany Guyette, became pregnant and gave birth to their son Dominik in September 1997.71

On August 6, 1998, Jared attacked Tiffany while she was holding Dominik. He was charged with domestic assault and malicious destruction of property. Tiffany told authorities that Jared had been talking about using steroids.72 During the early 2000s, Jared was arrested many times for assaulting girlfriends, and sometimes their friends. But thanks to the Remys’ lawyers and lenient judges, he escaped with little more than slaps on the wrist. The full extent of Jared’s history of violence was not known to the public until a Boston Globe investigation in 2014.73

Despite Jared’s issues, Remy’s work life proceeded smoothly. The NESN booth had a new addition in 2001 – Don Orsillo. Bob Kurtz had left to broadcast Minnesota Wild hockey. Orsillo, a PawSox radio/tv broadcaster, approached Remy who suggested that NESN management give him an audition. He was hired. “He was an absolute joy to work with,” Remy said. “We clicked so well.”74

Like Martin and McDonough had done for him, Remy was a steadying guide for Orsillo as he acclimated to his new job. “Jerry was huge in really helping me get through that process,” Orsillo said.75 Orsillo meshed perfectly with Remy, acting as his playful sidekick.76 Their repartee was often inspired by off-the-field scenes which the camera crew captured and aired live. Fans fondly remember great moments such as the pizza throw, the boob grab, the guy who got confused by his own poncho, and Remy losing a tooth. Perhaps Remy delivered his best line during the lunar eclipse of May 2003. Orsillo asked, “A lunar eclipse is when the sun crosses in front of the moon, right?” Remy responded, “We wouldn’t be around here very long if that happened.”77

The 2001 Red Sox embraced the label “Dirt Dogs,” for their scrappy play. McDonough started calling Remy the “RemDawg” and the nickname stuck. Ratings hit an all-time high as the Red Sox improved in the early 2000s, and Remy’s star ascended with them. With a partner, he launched a website called TheRemyReport.com and started merchandising his name and personality through “RemDawg” t-shirts, stuffed toys, books, and a hot-dog stand outside of Fenway.78 The fan frenzy peaked when the Red Sox won the World Series in 2004, their first championship in 86 years.

In the summer of 2004, Jared was arrested for assaulting another girlfriend. Prosecutors recommended that he find a job. The Red Sox hired him as a Fenway security guard.79

The popular Sean McDonough was let go in 2005, leaving Orsillo to handle all the games with Remy. McDonough chalked it up to the fact that he was being paid $5,000 more per game than Orsillo.80

On October 3, 2007, the Red Sox fan club announced Remy’s election as President of Red Sox Nation.81 He had truly become the face and voice of Boston baseball. The Red Sox went on to win the World Series, beating the Rockies in four games. In 2008, Remy opened the first of several sports-bar/restaurants bearing his name.

During the 2008 season, the Red Sox suspended Jared Remy for using steroids. Major League Baseball, with Boston’s assistance, opened an investigation into whether he might have supplied steroids to players. Jared scoffed at the idea that he was a steroid dealer, saying, “I go to my dad for money.”82 The conclusions of the investigation were never released, but Jared was fired in September.83 His new girlfriend Jennifer Martel gave birth to their daughter, Arianna, that month.

In the booth, Orsillo noticed Remy’s mood growing darker. “There were games when he was going through depression that Jerry was really quiet. I knew he was struggling,” Orsillo remembered. “Sometimes you could just tell he was going into a kind of a shell or haze, whatever it was. It kind of overtook him.”84

During the winter of 2008, Remy fell ill with symptoms resembling bronchitis or pneumonia. A chest CT scan by Red Sox team physician Dr. Larry Ronan revealed a “cancerous mass.” The tobacco habit he started at age 16 had taken its toll. 85 After an operation to remove the mass, Remy came down with an infection, and his situation was serious for a time.86

Remy’s severe depression and anxiety returned. He made it through March and April, but on a road trip to Tampa in May, he found himself frozen with panic. “I’m a mess. I can’t leave my room,” he told his producer Russ Kenn.87 Phoebe had to fly down to collect him and bring him home. NESN granted Remy leave for several weeks. After a medication adjustment improved his condition, he returned to the booth for some home games late in the 2009 season and resumed full-time work in 2010.88

On August 13, 2013, Jared was arrested for assaulting Jennifer. Two nights later Jared confronted Jennifer at her home and stabbed her to death.89 Phoebe informed Remy as he was boarding a team flight from Toronto to Boston.90

After a few days of silence, Remy, always active on social media, sent a tweet reading: “Son or not, I am at a loss for words articulating my disgust and remorse over this senseless and tragic act. We are heartbroken.”91 Jared’s initial plea was not guilty, as he was considering a defense based on either insanity or his long-term steroid abuse.92

On March 22, 2014, the Boston Globe published its investigation with a timeline of Jared’s documented offenses.93 It showed Jared’s long history of domestic abuse, violent behavior, and avoidance of punishment, calling him the “king of second chances.”94 While the Globe noted the influence of Jerry Remy’s powerful name and privilege, it also cited “extraordinary deference by the courts.”95 The story provoked public anger, including calls for Remy’s resignation from NESN.96 Remy declined to step aside. Tom Werner sent an email to the Globe expressing his sympathy to the Martel family and supporting Remy’s decision to return to the broadcast booth.97

Remy spoke out after the article. “I don’t know if I’d do things differently,” he told WEEI radio. “We did the best we possibly could. We failed, we failed. It’s that plain and simple.”98

Jared ultimately pleaded guilty to Jennifer’s murder, and was sentenced to life in prison without parole.99

Meanwhile, Remy’s cancer returned. He went through radiation treatments while calling games in 2015. He missed games in 2016, and in 2017 he weathered surgery and increasingly extensive cancer treatments.

He cut back his travel in 2019, and NESN used a three-man team – Dave O’Brien doing play-by-play, with Remy and Dennis Eckersley as analysts – for 30 games. Since 2009, Eckersley had been filling in during Remy’s absences. Remy and Eckersley had been Red Sox teammates and they had a good rapport. “We came here in 1978 together, he from the Angels, me from the Indians,” Eckersley noted. “We played together a long time. He was a great friend and a great teammate.”100

In the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, NESN broadcast all games from its studios in Watertown, Massachusetts. Because of Remy’s compromised health, the three men were seated at a distance, but still in the same room so that they could maintain eye contact.101

This setup may have strengthened the bond between Remy and Eckersley. They had much in common: Eckersley, despite his breezy demeanor, had also endured much heartbreak in his private life.102 The talk between them was honest and unguarded, two veteran ballplayers reminiscing and sharing funny stories. “It worked because he was receptive to it. … It was just magic,” Eckersley said.103

The Red Sox floundered that year, finishing last in their division with a winning percentage of .400, so there was an opportunity for the two of them to ramble and joke around. “Man, I loved his laugh,” Eckersley recalled. “He’d get rolling and couldn’t stop himself from laughing. … I tried like hell to get him to laugh just to hear it.”104

During one of the last games of the season, they talked about old adversaries, and the mood turned elegiac. After identifying George Brett as a ballplayer who seemed to enjoy his time on the field, Eckersley mused, “Wouldn’t it be great, Jerry, to have a good time. I never had a good time. Well, I looked like I did.” “Neither one of us had a good time,” Remy replied.105

On August 4, 2021, Remy withdrew from broadcasting and issued a statement that he was resuming his treatment for cancer. He added, “As I’ve done before and will continue to do, I will battle this with everything I have.”106

On October 5 Remy appeared at Fenway before the AL Wild Card game against the Yankees. Smiling, with an oxygen tube in his nose, he threw out the first pitch to Eckersley. After catching it, Eckersley walked up and embraced him. “When I went out to hug him, I said, ‘I love you, and we all love you, see?’ ” Eckersley said later. “My last text to him was the next morning, telling him, ‘It was a privilege to be there last night.’ And he said, ‘I’m glad it was you.’”107

Remy died on October 31, 2021. He was survived by Phoebe, his wife of 47 years; his three children, Jared, Jordan, and Jenna; and two grandchildren, Dominik and Arianna, Jared’s son and daughter. Remy is buried at Linwood Cemetery in Weston, Massachusetts. Jared is serving his life sentence in the medium-security prison in Shirley, Massachusetts.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rick Zucker and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Photo credits: Boston Red Sox and Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Neil Swidey, “The Other Side of RemDawg,” Boston Globe, April 19, 2009: R18 (“Swidey”).

2 Matthew Shaer, “Red Sox Legend Jerry Remy is Ready to Talk About, Well, Everything,” Boston Magazine, April 3, 2019. https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2019/04/03/jerry-remy/ (“Shaer”).

3 Swidey: R18.

4 Shaer.

5 Jerry Remy and Nick Cafardo: If These Walls Could Talk: Stories from the Boston Red Sox Dugout, Locker Room, and Press Box (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2019), xvii (hereinafter, “Remy and Cafardo”).

6 Swidey: R19.

7 Swidey: R19.

8 Swidey: R18; Remy and Cafardo: 4-5.

9 Shaer.

10 Shaer.

11 Remy and Cafardo: 215.

12 Remy and Cafardo: 4.

13 Remy and Cafardo: 50.

14 Remy and Cafardo: 4.

15 Remy and Cafardo: 6.

16 The all-star game at Fenway Park on August 1, 1969 was sponsored by the Hearst organization. Remy was on the Sunday Advertiser team. According to research by Alan Cohen, on August 1, 1969, the Sunday Advertiser squad defeated the Record-American squad, 4-1. Sixteen-year-old Jerry Remy got infield hits in the first and third innings and drove in a fifth inning run with a fly ball. Ed Gillooly and Kevin Mannix, “Walsh, White Voted Top Sandlotters,” Boston Record-American, August 2, 1969: 36.

17 Remy and Cafardo: 6.

18 Remy and Cafardo: 8.

19 Remy and Cafardo. 8.

20 Remy and Cafardo: 9.

21 Remy and Cafardo: 9.

22 Remy and Cafardo: 9.

23 Remy and Cafardo: 10-11.

24 Remy and Cafardo: 12.

25 Swidey: R19.

26 Remy and Cafardo: 13.

27 Jerry Remy with Corey Sandler, Watching Baseball: Discovering the Game Within the Game, fourth edition (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2008), 143.

28 Remy and Cafardo: 14-15.

29 Remy and Sandler: 143.

30 Remy and Sandler: xi.

31 Remy and Cafardo: 17-18.

32 Remy and Cafardo: 215.

33 Remy and Cafardo: 153-154.

34 Remy and Cafardo: 31.

35 Remy and Cafardo: 18.

36 Remy and Cafardo: 24.

37 Remy and Cafardo: 25.

38 Bill Madden, “All-Stars Clash Tonight”, Rutland Daily Herald, July 11, 1978: 6.

39 Remy and Cafardo: 29.

40 Donie Bush achieved the same feat with Detroit during the 1909-1912 seasons, but he had played in 20 games in 1908.

41 Remy and Cafardo: 217.

42 Steve Wulf, “Up Against the Wall,” Sports Illustrated, August 8, 1984. https://vault.si.com/vault/1984/08/06/up-against-the-wall

43 Joe Giuliotti, “Battling Remy Ready After Injury Siege,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1980: 47.

44 Joe Giuliotti, “Friendly Fenway Boston Waterloo,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1980: 37.

45 Peter Gammons, “Mariners need just one inning to win marathon in 20th, 8-7,” Boston Globe, September 5, 1981: 21.

46 Joe Giuliotti, “AL East: Remy Achieves Cherished Goal,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1982: 42.

47 Joe Giuliotti, “Remy Delivering Key Bosox Hits,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1982: 38.

48 Joe Giuliotti, “Buckner Undergoes Elbow Surgery,” The Sporting News, November 5, 1984: 54.

49 Joe Giuliotti, “Waived Remy to Get Chance in Spring,” Sporting News, December 23, 1985: 36.

50 Joe Giuliotti, “Remy Bows to Reality,” Sporting News, April 21, 1986: 18.

51 Swidey: R19.

52 Remy and Cafardo: 216.

53 Remy and Cafardo: 152.

54 Remy and Cafardo: 154.

55 Remy and Cafardo: 153.

56 Remy and Cafardo: 155.

57 Remy and Cafardo: 155.

58 Clip from game broadcast, “Jerry Remy puts an “R” at the end of names and words. Don Orsillo laughing hysterically,” posted on YouTube in 2015.

59 “Martin was told by NESN a day before the 1992 season ended that he was no longer in their plans. ‘I don’t like to leave, and I don’t like to leave this way,’ he said after his final broadcast. ‘I wasn’t quite ready for it. They said I hadn’t done anything wrong, but who knows what that means? I think they may be getting a more multi-purpose person in there … and (someone who’s) younger.”’ Bob Lemoine, “Ned Martin,” SABR BioProject.

60 Remy and Cafardo: xi.

61 Remy and Cafardo: 156.

62 Remy and Cafardo: xii.

63 Remy and Cafardo: 157.

64 Remy and Cafardo: xi-xii.

65 Shaer.

66 Remy and Cafardo: 192.

67 Remy and Cafardo: 193.

68 Remy and Cafardo: 196.

70 Eric Moskowitz, “For Jared Remy, Leniency was the Rule Until One Lethal Night,” Boston Globe, March 23, 2014: A1, A12 (“Moskowitz”).

71 Moskowitz: A13.

72 Moskowitz: A13.

73 Moskowitz: A1.

74 Remy and Cafardo: 159.

75 Remy and Cafardo: 225.

76 Remy and Cafardo: 225.

77 Swidey: R20.

78 Remy and Cafardo: 173.

79 Moskowitz: A14.

80 John Howell, “Football Under the Tree but No Sox,” Hartford Courant, December 24, 2004: 230.

81 Gary Dzen, “Remy wins,” Boston.com, October 3, 2007. https://www.boston.com/sports/extra-bases/2007/10/03/remy_elected_pr/

82 Marcella Bombardieri, “For the accused, it’s been a life with few high points, and many years of trouble,” Boston Globe, August 17, 2013: A1.

83 Thomas Farragher, “Sox fired two in steroids case,” Boston Globe, August 2, 2009: A1. Excerpts from the article:

Both men were fired in a case that speaks to both Major League Baseball’s new intolerance for steroids and its inconclusive efforts to investigate suspicious cases. The security staffers said they were dismissed after what they termed a cursory inquiry by Major League Baseball, and very limited questioning by the team – even though one of the guards says he swapped advice about steroids with David Ortiz’s close friend and personal assistant. Both men said they told investigators they had no direct knowledge of steroid use by Red Sox players, including Manny Ramirez or Ortiz, both of whom were named in a New York Times report last week as having tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs in 2003. But, in interviews with the Globe, both revealed clubhouse details that could have fueled a more zealous inquiry. And the investigation did not even resolve the basic question of where the steroids the security staffer was caught with came from. “I’m sure they were hoping I didn’t know anything,” said Jared Remy, one of the security staffers who lost his job. “It’s like they didn’t want to know. It’s like: Do we really want to know, or do we just want it to go away?”

84 Remy and Cafardo: 227.

85 Remy and Cafardo: 209.

86 Remy and Cafardo: 206.

87 Remy and Cafardo: 194.

88 NESN Staff, “Jerry Remy Feeling Much Better, Excited for Return to NESN Broadcast Booth,” NESN.com, April 2, 2010. https://nesn.com/2010/04/feeling-much-better-jerry-remy-excited-for-return-to-nesn-broadcast-booth/

89 Moskowitz: A15.

90 Remy and Cafardo: 200.

91 Wesley Lowery, “Jerry Remy expresses ‘disgust’ at son’s arrest in the fatal stabbing of girlfriend Jennifer Martel,” Boston Globe, August 18, 2013: A1.

92 UPI, “Jared Remy pleads not guilty in girlfriend’s slaying,” October 9, 2013. https://www.upi.com/Top_News/US/2013/10/09/Jared-Remy-pleads-not-guilty-in-girlfriends-slaying/78691381347746/

93 “Timeline: Jared Remy’s troubled past,” Boston Globe, March 23, 2014: A15.

94 Moskowitz: A12. Moskowitz wrote: A review of hundreds of pages of court files and police records revealed accounts that he terrorized five different girlfriends starting when he was 17, and that courts repeatedly let him off with little more than probation and his promise to stay out of trouble. He rarely did.

95 Editorial, “State judges bear blame for failing to curb Jared Remy,” Boston Globe, March 27, 2014: A14.

96 Chad Finn, “No reason to oust Remy,” Boston Globe, March 28, 2014: C2.

97 Dan Shaughnessy, “As glare intensifies, Remy resolves to stay put,” Boston Globe, March 28, 2014: A1

98 “Jerry Remy admits failure with son Jared, defends actions,” WCVB.com, March 28, 2014. https://www.wcvb.com/article/jerry-remy-admits-failure-with-son-jared-defends-actions-1/8198421

99 Eric Moskowitz, “Guilty plea and life in prison,” Boston Globe, May 28, 2014: A1.

100 WCVB-TV interview, “Dennis Eckersley reflects on catching emotional first pitch from Jerry Remy,” posted on YouTube on November 1, 2021. https://youtu.be/Z3wocQf1wtQ?si=vY_qbDskUhbDELKD

101 Chad Finn, “For NESN, remote call not awkward,” Boston Globe, July 23. 2020: D3.

102 Eckersley and his first wife Nancy adopted a baby girl they named Allie in 1996. In 2019, a reporter discovered her living in a homeless encampment in New Hampshire. “At age two Allie was diagnosed with mental illness,” the Eckersley family statement read, “which worsened considerably through the years, leading to multiple hospitalizations and eventually institutionalization.” Ray Duckler, “Homelessness can happen to anyone,” Concord Monitor, May 5, 2019: A1. She was arrested in 2022 on charges relating to abandoning her newborn son in a tent in the woods. The Eckersley family is attempting to obtain guardianship of the boy. Allie’s case is scheduled to go to trial in 2014. See also Associated Press, “Daughter of Dennis Eckersley, accused of abandoning newborn, faces trial next year,” May 12, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/baby-woods-dennis-eckersley-daughter-661261bd9398ea45b4b46079c5a6b134

103 TV Interview with Eckersley, “Dennis Eckersley reflects,” November 1, 2021.

104 Chad Finn, “Teammates had strong bond,” Boston Globe, November 1, 2021: C3.

105 Chad Finn, “Three winners in a lost season,” Boston Globe, October 4, 2020: C7.

106 Dakota Randall, “Jerry Remy Steps Away from NESN Red Sox Booth for Cancer Treatment,” NESN.com, August 4, 2021. https://nesn.com/2021/08/jerry-remy-cancer-nesn-red-sox-broadcast/

107 Finn, “Teammates had strong bond.”

Full Name

Gerald Peter Remy

Born

November 8, 1952 at Fall River, MA (USA)

Died

October 30, 2021 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.