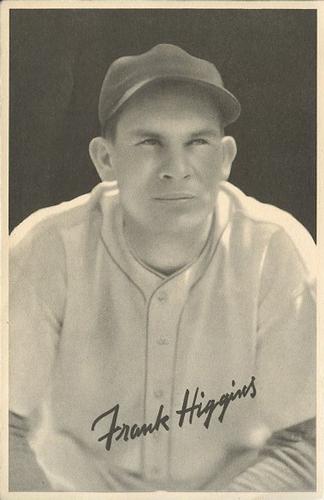

Mike Higgins

Mike Higgins was a fine player, a successful minor-league manager, a Manager of the Year in his first major-league season, and the face of the Red Sox for several years. But the fortunes of the club deteriorated during his tenure, and for many people Higgins became the face of that failure. While his team continued to slide, Higgins enjoyed real power in the organization for 11 years, during a time when the team desperately needed a new direction and he seemed unable to provide it. Most disturbingly, he has received a large share of the blame for the club’s long failure to field a black player. In fact, many historians have concluded that he was a vile racist, and that he alone kept the team from integrating for several years. All of these charges were leveled after Higgins’ death, so we unfortunately do not have his feelings on the matter.

Mike Higgins was a fine player, a successful minor-league manager, a Manager of the Year in his first major-league season, and the face of the Red Sox for several years. But the fortunes of the club deteriorated during his tenure, and for many people Higgins became the face of that failure. While his team continued to slide, Higgins enjoyed real power in the organization for 11 years, during a time when the team desperately needed a new direction and he seemed unable to provide it. Most disturbingly, he has received a large share of the blame for the club’s long failure to field a black player. In fact, many historians have concluded that he was a vile racist, and that he alone kept the team from integrating for several years. All of these charges were leveled after Higgins’ death, so we unfortunately do not have his feelings on the matter.

Michael Franklin Higgins Jr. was born on May 27, 1909, in Red Oak, Texas, about 20 miles south of Dallas. Mike was the youngest of three boys born to Michael Higgins and the former Mattie Orr, Irish Methodist farmers. The family moved to Dallas when Mike was a youngster, and Michael, Sr. spent the next 30 years as a policeman. The oldest son, Clen, was called Ox because of his size, and played football at the University of Texas. The middle boy, Jimmie, starred for Southern Methodist.

Mike’s rosy complexion gave him the name Pinky as an infant, a name he spent a lifetime unsuccessfully trying to shake. He took to baseball at a young age, playing for Tyler Street Methodist Church in the Dallas church league at age 11. At Adamson High School he starred in football, basketball, and baseball. After high school he earned an athletic scholarship to the University of Texas at Austin. He played fullback for the Texas team as a sophomore, earning all-conference honors, before giving up football to concentrate on baseball. He stayed in Austin for three years. After his junior year, he signed a contract with Philadelphia Athletics scout Mike Drennan for $3,500. Higgins had several other offers, but chose the Athletics because their third baseman, Jimmie Dykes, was 33 and likely nearing the end of the line.

After signing, Higgins spent the rest of the 1930 season with the major-league club, mainly as a pinch-hitter or defensive replacement. He had his first major-league hit, a single, on July 9 at Yankee Stadium. All told, he got into 14 games, knocking six hits in 24 at-bats. He spent the 1931 season playing for both San Antonio and Dallas in the Texas League, where he hit a combined .284 with 10 home runs in 131 games. The next season he played in the Pacific Coast League with the Portland Beavers. The PCL played a long schedule in those days, and Higgins took advantage, hitting 33 home runs and batting .326 in 189 games.

After the 1932 season, the financially struggling Athletics sold Al Simmons, Mule Haas, and Dykes to the Chicago White Sox for $100,000, clearing a spot for Higgins in the major-league lineup. The big right-handed hitter, a shade over 6 feet and 185 pounds, held his third-base spot for the next four years. He hit .314 in 1933, with 13 home runs and 99 RBIs. The next year he raised his average to .330, with 16 homers and 90 runs driven in. That year he was voted to start the All-Star Game at third base (he was hitting .360 at the time of the game), but manager Joe Cronin (the player-manager of the Washington Senators) instead used Higgins’ teammate Jimmie Foxx, a first baseman, all nine innings at third base.

Higgins suffered a sprained ankle in the spring of 1935, causing him to miss the first two weeks of the season and slump badly when he returned. He regained his hitting form in midseason, highlighted by a three-homer game against the Red Sox at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park on June 27. At the end of the year his average was .296, but he had belted a career-high 23 home runs and driven in 94 runs. The next season he dropped to .289 with just 12 home runs, but fielded his usually fine third base and made his second All-Star team, starting this time but striking out in both his at-bats (against Dizzy Dean and Carl Hubbell).

In December 1936, the Athletics dealt Higgins to the Red Sox for third baseman Billy Werber. Philadelphia spent several years in the 1930s shedding themselves of their best players, many of whom, including Foxx and Lefty Grove, were already on the Red Sox. Higgins was the subject of trade rumors for a few years before the Boston deal. Higgins and Werber were similar players, but Werber had not gotten along with player-manager Joe Cronin, and Boston was delighted to acquire the mild-mannered Higgins. He had two very good seasons with the Red Sox, hitting .302 and .303 and driving in 106 runs in each season. The highlight of his stay was the 12 consecutive hits (along with two walks) he made between June 19 and 21, 1938, breaking an AL record set by Cleveland’s Tris Speaker in 1920 and tying the major-league mark set by Johnny Kling of the Cubs in 1902. Walt Dropo of the Tigers later matched the record with 12 consecutive hits in 1952.

In December 1936, the Athletics dealt Higgins to the Red Sox for third baseman Billy Werber. Philadelphia spent several years in the 1930s shedding themselves of their best players, many of whom, including Foxx and Lefty Grove, were already on the Red Sox. Higgins was the subject of trade rumors for a few years before the Boston deal. Higgins and Werber were similar players, but Werber had not gotten along with player-manager Joe Cronin, and Boston was delighted to acquire the mild-mannered Higgins. He had two very good seasons with the Red Sox, hitting .302 and .303 and driving in 106 runs in each season. The highlight of his stay was the 12 consecutive hits (along with two walks) he made between June 19 and 21, 1938, breaking an AL record set by Cleveland’s Tris Speaker in 1920 and tying the major-league mark set by Johnny Kling of the Cubs in 1902. Walt Dropo of the Tigers later matched the record with 12 consecutive hits in 1952.

After the 1938 season, the Red Sox dealt Higgins to Detroit in a five-player deal that netted the Red Sox pitcher Elden Auker. Higgins was deemed expendable because of the promise shown by Jim Tabor in the minor leagues and in a brief 1938 call-up, and the club was looking for another steady starting pitcher. Higgins reportedly was told by Joe Cronin and Boston general manager Eddie Collins that he would have a job with the club if he needed one later on. They kept their word.

Higgins spent the next six years as the Tigers’ regular third baseman, hitting between .267 and .298 every season, averaging 10 home runs and 77 RBIs—a remarkably consistent set of seasons. His highlight came in 1940, when he helped the Tigers reach the World Series, where he hit .333 with three doubles, a triple, and a home run. Alas, Detroit lost the seven-game Series to the Cincinnati Reds. He made his third All-Star team in 1944, grounding out in a pinch-hitting appearance.

After the 1944 season, Higgins entered the US Navy and spent the year stateside, acting as player-manager for the Great Lakes Naval Station ballclub in 1945. He returned to the Tigers in 1946. After a slow start (.217 in 18 games), on May 19 the Tigers sold Higgins to the Red Sox, who were on their way to a pennant but needed a third baseman. Higgins, who turned 37 years old eight days after joining the Red Sox, shared the job with veteran Rip Russell, hitting .275 in 64 games and then starting all seven World Series games. He hit just .208 (5-for-24) as the Red Sox lost in seven games to the Cardinals.e

Higgins married Hazen French, his high school sweetheart, in 1935, and the couple raised two daughters, Diane and Elizabeth. Diane was an accomplished pianist, and Elizabeth a flutist. They always lived in Dallas, and Mike spent his offseasons fishing, cooking, and playing bridge. He was also a big fan of college football, especially his University of Texas Longhorns.

After the 1946 season, Higgins was offered a job managing in the Red Sox system—actually he was given a choice of two jobs. Toronto was a Triple-A club with a loose affiliation to the Red Sox, while Roanoke, in the Class B Piedmont League, was owned outright. Higgins took the Roanoke job, figuring it gave him more of a chance to work with players from the Red Sox system, and began his slow climb to the top. He spent two years in Virginia, winning the league championship in 1947 and finishing fourth in the eight-club loop the next year. He then managed two years at Birmingham of the Double-A Southern Association, finishing second each year. After the 1950 season, he was offered a major-league coaching job by Paul Richards, new manager of the Chicago White Sox, but he turned it down. He felt the Red Sox had been good to him, and that they would eventually come through.

In 1951, Higgins became the manager of the Louisville Colonels, the Red Sox Triple-A affiliate in the American Association. In his first season, Higgins finished in fourth place and was likely an interested observer when the Red Sox fired manager Steve O’Neill in October. Although general manager Joe Cronin wanted to hire Higgins, owner Tom Yawkey preferred Lou Boudreau, whom he had long admired as a player-manager with the Indians and who had played for the Red Sox as a reserve infielder in 1951. Boudreau got the job, and Higgins returned to Louisville for three more years. After fifth- and third-place finishes, the Colonels finished second in 1954 but won the league playoffs and also the Junior World Series over Syracuse, the champion of the International League. After the 1954 season, the Red Sox fired Boudreau and finally hired Higgins as their major-league manager; he was now 45 years old.

The soft-spoken Higgins was a popular choice. The Red Sox were going through a youth movement in the mid-1950s, and no one knew the Red Sox minor-league players better than Higgins, who had managed in the system for eight years. He had never finished below .500, even though his teams were often younger than the competition. “You can win minor-league pennants with former big leaguers on their way down,” Higgins said in 1956, “but that doesn’t do your parent club any good. If you finish last, but teach a promising youngster how to hit a curveball, you’ve done a lot better than if you win and don’t teach anybody anything.”

“Higgins is the greatest judge of human nature I have ever known,” said Charlie Wagner, a 1946 teammate and then the Red Sox’ assistant farm director. “He knows instinctively how to get the most out of young ballplayers.” As important, Ted Williams liked and admired Higgins, a change from Williams’ cold relationship with Lou Boudreau.

Higgins’ first year in Boston was beset with tragedy, and also with success. Harry Agganis, who had played for Higgins in Louisville in 1953, was one of the bright young players on the Boston team when Higgins arrived. After winning the starting first-base job and hitting well early in the 1955 season, Agganis began to complain of severe fever and chest pains. After a few weeks in and out of the hospital, Agganis died of a pulmonary embolism on June 27. The stunned team soldiered on. After a slow start to the season, the Red Sox passed .500 in late June and got to within three games of the first place in early September before fading. The club finished 84-70, a 15-game improvement over its 1954 pace. After the season, Higgins was named the Manager of the Year by several news organizations, including the United Press.

As a manager, Higgins was not particularly colorful or exciting, but in his early years was accommodating to the press and friendly and helpful to his players. That first year he was described as “a good, kind, unspectacular man, rugged and simple and given to uttering such homely phrases as ‘Rules are made to be broken’ and ‘A happy team is a winning team.’” The press threw him a birthday dinner in May 1955, and continued the practice in subsequent seasons. Joe Cronin, his boss, termed Higgins “solid,” referring to his demeanor, personality, and managerial strengths. At a banquet in 1955, Casey Stengel compared Higgins to Joe McCarthy, one of history’s greatest managers—not based on their accomplishments, but on their rectitude and problem-solving. The players thought he understood them. “He’s never forgotten he was a player himself,” said pitcher Dave Ferriss, who played with Mike in 1946 and coached under him with the Red Sox. When asked about his own managerial highlights, Higgins told a writer, “There are more thrills to playing than to managing.”

Higgins never again received the accolades he enjoyed in 1955, and his managerial years must be considered a disappointment. The youth movement was mainly a failure, and the club did not have the players to compete with the Yankees in the late 1950s. The popular Higgins’ first four clubs were fourth twice and third twice, finishing an average of 10 games over .500. One of the problems, though by no means the only one, was that while a steady stream of black stars was entering the game, the Red Sox did not have any of them.

In the years following Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers in 1947, the rest of the major leagues slowly followed suit. By the time Higgins managed his first major-league game in 1955, 12 of the 16 major league teams had integrated. The Red Sox had two minor-league players—infielder Pumpsie Green and pitcher Earl Wilson—who were not yet ready. Al Hirshberg, writing in his history of the team in 1973, claimed that Higgins “sometime in the 1950s“ told him, “There’ll be no niggers on this ballclub as long as I have anything to say about it.” Unfortunately, Higgins was not alive to answer this charge, and Hirshberg provided no additional details prior to his own death shortly after writing his book. Larry Claflin, also writing after Higgins’ death, said that Higgins called him a “nigger lover” (then spat tobacco juice on him) when Claflin asked him about recalling Pumpsie Green. All subsequent histories of the club have painted Higgins as a racist, largely because of these charges of racist language. Neither Claflin nor Hirshberg ever wrote anything like this while Higgins was alive and they were covering the club—in fact, Hirshberg wrote several glowing profiles of Higgins in his early days as manager.

Green and Wilson were both on the cusp of making the big-league club in 1959 and most observers felt that Green would stick. (Wilson had spent the previous two years in the military and needed some additional seasoning). The club received a lot of negative publicity because there were no accommodations in Scottsdale, Arizona, their spring training site, that would allow blacks. Green had to room in Phoenix, 15 miles away, and be driven to and from his motel. Green was farmed to Minneapolis while the Red Sox were barnstorming north, which led to howls of protests by local civil-rights groups. Green was no star prospect—a shortstop who had hit .253 in Triple-A the previous season—but his unique situation drew much attention. When he hit .320 in 98 games with Minneapolis, he was summoned to Boston in late July, followed a week later by Wilson. Higgins, however, was no longer the manager.

After four seasons over .500, the club was in last place at 31-42 on July 2 when general manager Bucky Harris (Joe Cronin had become president of the American League) fired Higgins, replacing him with Billy Jurges. Owner Tom Yawkey expressed admiration for Higgins, but said the club needed a change. In fact, Higgins was named a special assistant, helping Harris and Yawkey. The Red Sox finished the season in fifth place with a 75-79 record. But on June 10, 1960, with the Red Sox again in last place, at 15-30, the team fired Jurges and, after a week of indecision, Yawkey talked Higgins into returning to the dugout. Although the move was surprising, Higgins was still well respected as a handler of people. “That he will develop a higher morale among his players, and receive a stronger sports page support than Jurges was able to win, is certain,” wrote Dan Daniel in the New York World Telegram and Sun. The Red Sox played a little better under Higgins, 48-57, and managed to climb up to seventh place in the eight-team American League. Near the end of the season Yawkey fired GM Harris, and did not name another general manager. Higgins would assume the responsibilities of that post, giving him complete control over major-league personnel and all trades.

When Higgins lost the manager’s job the first time, he was still a fairly popular figure—the team had finished over .500 in all four of his complete seasons, and most observers considered the record to be a fair reflection of the talent Higgins had on hand. He also seemed to have a good relationship with the players and media. The second go-round was much different. He now largely controlled the talent coming in to the team, and he seemed unwilling or uninterested in making any changes. Later stories suggest that he was a heavy drinker, and that the situation had grown troublesome by the early 1960s. Worse, he drank with Yawkey, leading to the general impression that this was his only qualification for his huge role in the organization. If sportswriters of the day noticed such behavior, there was an unwritten code that it was considered off-limits for reporting.

On the other hand, if Higgins had reservations about having black ballplayers on his team, as was later alleged, he adjusted well to the reality once presented with them. When Higgins returned to the club, Pumpsie Green was playing fairly often in a reserve role—in 49 team games he had played in 43, with 16 as a starter. Higgins kept playing him the same way, until late August, when Green became the starting shortstop and leadoff hitter for the rest of the year. Just prior to Higgins’ return, the Red Sox traded Gene Stephens to the Orioles for Willie Tasby, a black man who became the club’s starting center fielder. In July, Higgins recalled pitcher Earl Wilson from Minneapolis, giving the team three black players. On August 20, the three men were in the same starting lineup for the first time, Green and Tasby hitting first and second in the batting order. (By contrast, the Yankees did not start three African-Americans in the same lineup until September 1965). Green has always been reluctant to talk about his role as a trailblazer, focusing instead on his trying to forge a major-league career.

Green says he never heard Higgins use a racial slur, but also, “You’d just get a feeling. He’d make his conversation as short as possible.” Wilson was more certain, and believed that Higgins did not like black players. “It’s not very hard to tell if a guy likes you or dislikes you,” says Wilson. “It’s like if a dog comes in a room, he can tell if a person likes him or dislikes him. It [Higgins’ supposed racism] was real, man.”

The difficulty in pronouncing a verdict is that the white players felt the same way. “I suppose he could have been a racist, being from Texas and all,” recalled Carl Yastrzemski. “But Mike was a very hands-off manager. Very stand-offish. He managed me for years and never said a word to me. I swear to God, he didn’t know who I was. He could walk right by me after a game and he wouldn’t say hello. He’d never say a word to you.”

Yastrzemski’s recollections are much different from the comments players made in Higgins’ early years. This is likely a reflection of Higgins being older and more powerful within the organization. In the early years he was a field manager who knew many of the players personally. By the 1960s he was running the team off the field as well, and had lost most of the personal connections he had had with the players. It could also be the case that his drinking problem was affecting his personality and his managing.

After the 1960 season, Ted Williams retired, bringing an end to a long chapter in Red Sox history. The club won 76 games each of the next two seasons, good for just sixth and eighth place in the new 10-team league. The team had just enough good players (a young Carl Yastrzemski, Pete Runnels, Frank Malzone) to avoid sinking to the cellar, but they were nowhere near contention. While the 1950s Higgins teams were first-division clubs, during his second tenure the club was uncompetitive and unpopular with the fans.

After the 1962 season, the Red Sox fired Higgins as manager, but remarkably named him as general manager, a role he had assumed (without title) for the past two years. Higgins and Yawkey remained good friends, drinking together, and hunting in the offseason, but nothing in Higgins’ recent performance suggested he ought to be running the organization. Most of the fans and press had come to think of Higgins as the main problem, but his position within the club was stronger than ever. The team got worse, and the fans stayed away: While the Red Sox had drawn more than 1.1 million fans in 1960, by 1965 the attendance was 650,000 for the season.

Johnny Pesky was the new manager, and the team stumbled to 76 wins (for the third straight year) in 1963 and then 72 in 1964. By all accounts, including Pesky’s, the two men did not get along. In fact, Pesky recounted more than one occasion where he would come to Higgins looking to improve the club with a trade, but the GM wouldn’t even put down his newspaper and look his field manager in the face. Higgins wanted to be the manager himself, so allowing him to be in charge of his own replacement could not have been expected to work. After Pesky’s first year, Higgins forced Pesky to fire Harry Dorish as pitching coach, a move that Pesky was still bitter about four decades later.

An inactive manager, in his new role Higgins was not an active trader. In late 1962, he dealt for Dick Stuart from the Pirates and Roman Mejias from the Colt 45’s—two right-handed power hitters to aim at the short wall in left field. Stuart hit 75 home runs over the next two seasons, but made life difficult for Pesky with his carefree attitude on and off the field. Mejias did not hit. Higgins made zero trades in 1963 and just two in 1964—the second of which was to dispose of Dick Stuart, to the Philadelphia Phillies for left-handed pitcher Dennis Bennett. With two games left in the 1964 season, Higgins fired Pesky and replaced him with Billy Herman. Higgins and Herman were friends, and Higgins had forced Pesky to keep him on as a coach in 1963. The 1965 team fell to 62-100, its worst record in 33 years.

One of the pivotal dates in Red Sox history was September 16, 1965. After years of bad publicity and fan outcry, Yawkey finally decided to fire Higgins. The club announced that there would be a press conference at Fenway Park after that day’s game. In the meantime, pitcher Dave Morehead threw a no-hitter against the Indians. Fearing the announcement would leak, Yawkey held the press conference, unfortunately upstaging Morehead’s wonderful performance. After 11 years of power with the organization, a period of slow and steady decline for the club, Mike Higgins was through in Boston.

Dick O’Connell, who had been a vice president running the business side of the club for several years, was given complete control of the organization and soon turned the franchise around. In early October, Higgins was hired by the Houston Astros as a special scout, looking at amateurs as well as major leaguers.

Higgins’ drinking problem continued and eventually led to tragedy. In February 1968, his car struck and killed a Louisiana highway worker and injured two others. He was convicted of driving while intoxicated and sentenced to four years of hard labor in Louisiana State Penitentiary. He was co-operative and penitent with authorities, but so anguished that he suffered two heart attacks, and lost 30 or 40 pounds, between his conviction and his January 1969 sentencing. “It’s just one of those tragic cases,” said District Attorney Ragan Madden. After two months of light prison duty, he was paroled. “There are criminals and there are people like Mr. Higgins,” said a prison official. “I wish we could let all of those like Mr. Higgins go.” He planned to return to his job as Astros scout.

On March 21, 1969, less than 48 hours after his release from prison, he suffered another heart attack and was rushed to St. Paul hospital in Dallas. Within minutes he was dead. He was just 59 years old. He was survived by his wife, two daughters, and two grandchildren.

Four years after Higgins’ death, Hirshberg wrote his book charging Higgins with being an obstructionist on integration. Many subsequent histories of the Red Sox have focused on the team’s racism. Although many in the organization have been blamed, history has assigned Higgins alone the burden of overt racism due to the claims that he made vile racist statements. He had a long history in the game, most of which has been overshadowed by this issue for the past few decades.

Sources

Dan Daniel, “Tough Job Ahead for Higgins,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, June 13, 1960.

Mike Gillooly, “Higgins—He’s Solid,” Baseball Digest. May 1956

Al Hirshberg, “The Pinky in the Red Sox Boot.” Sports Illustrated, July 25, 1955.

Al Hirshberg, “Savvy Skipper of the Red Sox,” Saturday Evening Post, July 21, 1956.

“Leaves From a Fan’s Scrapbook,” The Sporting News, January 5, 1939.

Dan Shaughnessy, “Red Sox Pained By Their Past: Stung By Charges of Racism, Team Has Taken Positive Steps,” Boston Globe, March 3, 1997.

Full Name

Michael Franklin Higgins

Born

May 27, 1909 at Red Oak, TX (USA)

Died

March 21, 1969 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.