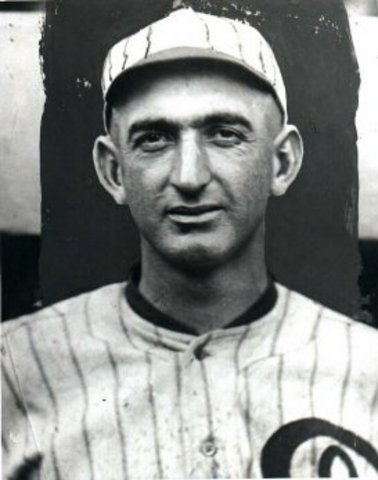

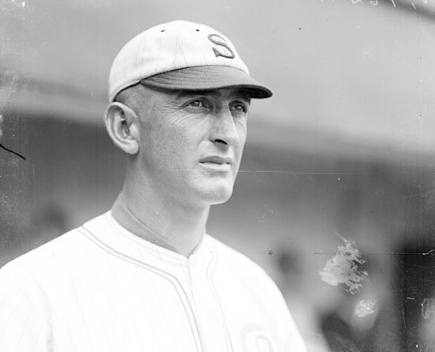

Shoeless Joe Jackson

Shoeless Joe Jackson was a country boy from South Carolina who never learned to read or write much (“It don’t take school stuff to help a fella play ball,” he once said1) but is widely hailed as the greatest natural hitter in the history of the game. A left-handed batter and right-handed thrower, Jackson stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 178 well-built pounds. He belted sharp line drives to all corners of the ballpark, and was fast enough to lead the American League in triples three times. He never won a batting title, but his average of .408 in 1911 still stands as a Cleveland team record and a major-league rookie record.

Shoeless Joe Jackson was a country boy from South Carolina who never learned to read or write much (“It don’t take school stuff to help a fella play ball,” he once said1) but is widely hailed as the greatest natural hitter in the history of the game. A left-handed batter and right-handed thrower, Jackson stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 178 well-built pounds. He belted sharp line drives to all corners of the ballpark, and was fast enough to lead the American League in triples three times. He never won a batting title, but his average of .408 in 1911 still stands as a Cleveland team record and a major-league rookie record.

Unfortunately, after Cleveland traded him to the Chicago White Sox, Jackson’s career ended ignominiously because of his involvement in the infamous Black Sox Scandal of 1919. He was expelled from the game in his prime, and for that reason he has never received a plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown.

Joseph W. Jackson was born on July 16, 1887, in rural Pickens County, South Carolina.2 His father, George, was a laborer who settled in nearby Greenville soon after Joe’s birth and found employment at Brandon Mill, a textile factory that paid $1.25 a day. Brandon Mill stood on the west side of Greenville, and there George Jackson and his wife, Martha, set up a household in one of the small, company-owned houses. Joe, the oldest of eight children, began working at the mill at age 6 or 7. He never attended school, but he did learn to play baseball. Brandon Mill sponsored a team that faced squads from other mills and factories, and Joe earned a spot in the lineup when he was 13 years old. He had his father’s unusually long arms and he excelled at throwing and hitting a ball. He soon became renowned throughout the Carolinas as an outfielder, pitcher, and home-run hitter, which were known throughout the mill league as “Saturday Specials.”

A local fan named Charlie Ferguson made bats in his spare time, and he chose a four-by-four beam from the north side of a particularly strong hickory tree to make one for young Joe Jackson. It measured 36 inches long and weighed about 48 ounces. Ferguson darkened the bat with tobacco juice; Joe called it “Black Betsy” and eventually took it to the major leagues.

Joe played for factory teams and semipro clubs until 1908, when Greenville obtained a franchise in the Carolina Association, a new Class D league on the lowest level of Organized Baseball. He signed a contract with the Greenville Spinners for $75 a month. Jackson, who was making about $45 a month between working at the mill and playing ball, reportedly told manager Tom Stouch, “I’ll play my head off for $75 a month.”3 Although Jackson later learned to trace his own name, he signed his first professional contract with an “X.”

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

The strong, agile 20-year-old quickly became the biggest star in the Carolina Association, leading the league with a .346 average, making phenomenal throws and catches in center field, and serving as mop-up pitcher. A reporter for the Greenville News tagged him with his nickname that season, when Joe played a game in his stocking feet because his new baseball shoes were not yet broken in. For the rest of his life he was known as Shoeless Joe Jackson. He didn’t like his nickname and later told Atlanta reporter Furman Bisher, “I’ve read and heard every kind of yarn imaginable on how I got the name. … I never played the outfield barefoot, and that was the only day I ever played in my stockinged feet, but it stuck with me.”4

He also gained a wife that year, marrying 15-year-old Katie Wynn on July 19, 1908. She had brown hair and brown eyes, and some education, since she could read and write. She remained married to Joe for 43 years, and until the day Joe died she wrote his letters, managed his money, and read his contracts in and out of baseball.

In August 1908 Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack bought Jackson’s contract for a reported $900.5 Joe was reluctant to go north, and Greenville manager Stouch accompanied him on the train ride to Philadelphia. Joe made his first major-league appearance on August 25, and singled in his first trip to the plate. However, Joe was homesick, and three days later he boarded a train back to Greenville. He returned in early September, but Philadelphia, a city of two million people, was frightening to the illiterate country boy. Jackson jumped the team once more before the 1908 season ended, finishing his first major-league stint with three hits in 23 at-bats.

Jackson bounced between Philadelphia and the minors for the next two years. He won batting titles at Savannah in 1909 and at New Orleans in 1910, but did not hit well in Philadelphia in a 1909 late-season call-up. Joe admired manager Connie Mack (“a mighty fine man [who] taught me more baseball than any other manager I had”6) but he did not get along with his A’s teammates, many of whom teased him mercilessly about his illiteracy, which he tried to hide, and lack of polish. Mack reluctantly decided that Joe would never succeed in Philadelphia, and traded him to the Cleveland Naps for outfielder Bris Lord and $6,000 in July 1910. In mid-September, at the conclusion of New Orleans’ season, Joe reported to Cleveland.

Cleveland was a smaller city than Philadelphia. Many of Jackson’s new teammates were either Southerners or had played in the South, so Joe fit in well. Playing in right field and center field, Joe batted .387 in the final month of the 1910 season and claimed a permanent place in the Cleveland lineup.

In 1911 he made a major leap to stardom, battering American League pitching for 233 hits, 45 doubles, 19 triples, and a .408 batting average. He did not win the batting title (Detroit’s Ty Cobb batted .420), but he set Cleveland team records for hits, average, and outfield assists (32) that still stand (as of 2021). His torrid hitting helped lift the Naps to a third-place finish. Cobb paid tribute to Jackson as the season ended. “Joe is a grand ball player, and one who will get better and better. There is no denying that he is a better ball player his first year in the big league than anyone ever was.”7

In 1911 he made a major leap to stardom, battering American League pitching for 233 hits, 45 doubles, 19 triples, and a .408 batting average. He did not win the batting title (Detroit’s Ty Cobb batted .420), but he set Cleveland team records for hits, average, and outfield assists (32) that still stand (as of 2021). His torrid hitting helped lift the Naps to a third-place finish. Cobb paid tribute to Jackson as the season ended. “Joe is a grand ball player, and one who will get better and better. There is no denying that he is a better ball player his first year in the big league than anyone ever was.”7

Jackson swung the bat harder than most of his contemporaries, and players swore that his line drives sounded different from anyone else’s. Many other players held their hands apart on the bat and punched at the ball, but Joe put his hands together near the bottom of the handle and took a full swing. “I used to draw a line three inches from the plate every time I came to bat,” Jackson said many years later. “I drew a right angle line at the end of it, right next to the catcher, and put my left foot on it exactly three inches from home plate.”8 He stood in the box, feet close together, then took one long step into the pitch and ripped at it with his left-handed swing. “I copied my swing after Joe Jackson’s,” Babe Ruth told Grantland Rice in 1919. “His is the perfectest.”9

Though the Naps fell from third place to fifth in 1912, Jackson batted .395, with 121 runs scored, 226 hits, and 30 outfield assists. He also set a new American League record with 26 triples, a mark that was tied by Sam Crawford in 1914 but has never been surpassed. However, Joe once again finished second in the batting race to Cobb, who batted .409 for the Tigers. “What a hell of a league this is,” Jackson wailed to a reporter. “I hit .387, .408, and .395 the last three years and I ain’t won nothing yet!”10

Jackson displayed his power on June 4, 1913, when he belted a fastball from the Yankees’ Russ Ford; the hit bounced off the roof of the right-field grandstand at the Polo Grounds and into the street beyond. The newspapers claimed that the blast traveled more than 500 feet. Jackson’s .373 average that year trailed Cobb once again, but he led the league in hits (197), doubles (39) and slugging (.551), finishing second in the Chalmers Award balloting. His total of walks also increased sharply, from 54 to 80.

Joe turned down offers from the new Federal League in early 1914, though two Cleveland pitchers joined the new circuit and left the Naps shorthanded on the mound. Federal League raids and the sudden decline of Nap Lajoie caused the Naps to drop from contention, and injuries to Jackson and shortstop Ray Chapman doomed them to last place for the first time in their history. Forced by a broken leg to miss 35 games, Joe saw his average dip to .338 with only 61 runs scored and 53 runs batted in, and he posted new career lows in the speed-dependent categories of triples and stolen bases.

Controversy swirled around Jackson during the 1915 season. He had spent the winter months headlining a vaudeville show that drew curious crowds throughout the South. Joe enjoyed the theatrical life so much that he refused to report for spring training, threatening to quit baseball and begin a new career on the stage. Katie Jackson reacted poorly to that idea, and filed for divorce that March (though she and Joe soon reconciled). In May, team owner Charles Somers ordered manager Joe Birmingham to move Jackson to first base to make room for rookie Elmer Smith in the outfield. Joe played 30 games at first, but the experiment ended when Joe left the lineup with a sore arm. Somers became incensed when Birmingham blamed the position switch for Jackson’s injury, and the team owner soon fired Birmingham, appointing coach Lee Fohl to succeed him.

In 1915 Somers, teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, decided that he could not afford to keep his two best players, Jackson and Chapman. He needed to trade one and rebuild the ballclub (which was renamed the Indians after the team sold Lajoie to Philadelphia that spring) around the other. Somers’ mind was made up when the newspapers reported that the Federal League had offered Jackson a multiple-year contract at a salary of $10,000 per year. Somers feared that Jackson would bolt for the new circuit, leaving the Indians with nothing in exchange, so the Cleveland owner solicited offers for his cleanup hitter.

Jackson, who at the time was in the second season of a three-year contract for $6,000 a year, was not opposed to a trade. “I think I am in a rut here in Cleveland,” he told local sportswriter Henry Edwards, “and would play better somewhere else.”11 Indeed, Jackson’s batting average had now declined for four consecutive years. The Washington Senators offered a package of players for Jackson, but Somers rejected the bid to await a better one, which soon came from the Chicago White Sox. Owner Charles Comiskey coveted Jackson, and sent his secretary, Harry Grabiner, to Cleveland with a blank check. “Go to Cleveland,” Comiskey ordered, “watch the bidding for Jackson, [and] raise the highest one made by any club until they all drop out.”12

On August 21, 1915, Grabiner and Somers reached an agreement. Somers signed Joe to a three-year contract extension at his previous salary, then sent him to Chicago for $31,500 in cash and three players (outfielders Bobby Roth and Larry Chappell and pitcher Ed Klepfer) who collectively had cost the White Sox $34,000 to acquire. In terms of the total value of cash and players, this $65,500 transaction was the most expensive deal ever made in baseball up to that time.

Joe’s five-year stay in Cleveland ended with some sniping from the sports pages. Henry Edwards of the Plain Dealer criticized Jackson on his way out of town. “While he does not admit it, he was becoming … a purely individual player who sacrificed team work for Joe Jackson. … If he were still the Jackson of 1911, 1912, and 1913, the team would not have let him get away.”13

Jackson joined a contending team, one that featured four future Hall of Famers (second baseman Eddie Collins, catcher Ray Schalk, and pitchers Red Faber and Ed Walsh). Jackson hit poorly (for him) in the last six weeks of the 1915 season, and some observers believed that Joe’s career was on the downslide. However, he rebounded in 1916, batting .341 with a league-leading 21 triples as the White Sox challenged Boston for the league lead. Chicago finished second that season, but roared to the pennant with a 100-win season in 1917 despite a subpar performance by Jackson, who was hobbled all year after he sprained an ankle in spring training. Joe’s average dipped to .277 in early September, but he finished with a flurry of hits that lifted his final mark to .301.

With the pennant safely clinched, the White Sox sent Jackson and Buck Weaver to Boston for an all-star game to benefit the family of the popular player-turned-sportswriter Tim Murnane, who had died in February. Before the game, Jackson won a distance-throwing competition by heaving a ball 396 feet, 8 inches, which was said to be a modern record for a big leaguer.14 The all-stars, with an outfield of Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Jackson, and Walter Johnson on the mound, lost 2-0 to Babe Ruth and the Red Sox.

During the World Series New York Giants manager John McGraw used left-handed starting pitchers in four of the six games in a bid to neutralize the hitting of Collins and Jackson, but Joe batted .304 and saved the first game with a circus catch in left field. Red Faber won three decisions as the White Sox defeated the Giants four games to two for their second World Series championship, and the last one they would win for more than eight decades. Joe celebrated the victory, and the $3,669.32 winning share that went along with it, by purchasing a new Oldsmobile Pacemaker from a dealership in his new home of Savannah, Georgia, where he and Katie had moved to after his trade to the White Sox.

The White Sox were rocked by the entry of the United States into World War I. Several Chicago players enlisted in the military, while others were drafted in the early months of 1918. Joe, as a married man, was granted a deferment by his hometown draft board in Greenville, but after he played 17 games with the White Sox the board reversed its decision and ordered him to report for induction.15 Instead, Jackson found employment at a Delaware shipyard, where he helped build battleships and played ball in a hastily assembled factory circuit, the Bethlehem Steel League. Jackson was the first prominent player to avoid the draft by opting for war work, for which he was severely criticized in the sporting press, especially in Chicago.

When two of Jackson’s close friends, pitcher Lefty Williams and reserve catcher Byrd Lynn, followed him into the shipyards, owner Charles Comiskey swore he would not let any of them return to his team. “There is no room on my club for players who wish to evade the army draft by entering the employ of ship concerns!” he fumed.16 But after a sixth-place finish and the war’s end, he changed his tune. Jackson won the factory league batting title with a .393 average and helped lead the Harlan & Hollingsworth team to the championship among shipyards on the Atlantic coast, but the controversy permanently damaged his relationships with the Chicago sportswriters.

With little leverage, Jackson signed a new one-year contract for $6,000 — the same salary he had been receiving since 1914 — and returned to the White Sox. He was healthy again, and led the club in batting as the White Sox grabbed first place and held it for most of the 1919 season. Joe finished fourth in the league in batting with a .351 mark, his best average since 1913, with 181 hits and 96 runs batted in. Faber, Chicago’s leading pitcher, was sidelined late in the season with a sore arm, but Eddie Cicotte (29-7) and Lefty Williams (23-11) picked up the slack and pitched the White Sox into a comfortable lead in the standings. On September 24 Jackson drove home the winning run in the pennant-clinching game against the St. Louis Browns.

The White Sox were considered the most talented team in baseball, but they were also one of the unhappiest. The biggest problem facing the team was the same one that had been festering for several years. Eddie Collins, Red Faber, and Ray Schalk made up one clique, while Chick Gandil, Fred McMullin, Swede Risberg, and Buck Weaver made up an opposing faction. The two groups sniped at each other all season long. “The wonderful (Philadelphia) Athletic teams I played for believed in teamwork and cooperation,” Collins said many years later. “I always thought you couldn’t win without those virtues until I joined the White Sox.”17 A third group, including Jackson, Happy Felsch, and Lefty Williams, rarely spoke to the college-educated Collins and Faber, less out of animosity than out of a lack of common interests.

Late in the season, first baseman Chick Gandil, the leader of the first group, concocted a plan to fix the coming World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Jackson, according to his own later admissions, rebuffed Gandil’s first offer to throw the Series for $10,000 but he later agreed to participate after Gandil upped the offer to $20,000 — an amount more than three times his annual salary.18 Jackson had nothing to do with the planning of the fix; unlike Gandil, he had no contacts in the netherworld of gambling and nightlife. Joe’s participation consisted solely of trusting Gandil, a stunning amount of faith in a man whom he didn’t know very well. It was an incredible lapse of judgment, as well as a failure of character, on Jackson’s part.

Late in the season, first baseman Chick Gandil, the leader of the first group, concocted a plan to fix the coming World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Jackson, according to his own later admissions, rebuffed Gandil’s first offer to throw the Series for $10,000 but he later agreed to participate after Gandil upped the offer to $20,000 — an amount more than three times his annual salary.18 Jackson had nothing to do with the planning of the fix; unlike Gandil, he had no contacts in the netherworld of gambling and nightlife. Joe’s participation consisted solely of trusting Gandil, a stunning amount of faith in a man whom he didn’t know very well. It was an incredible lapse of judgment, as well as a failure of character, on Jackson’s part.

Jackson, who ultimately received only $5,000, batted .375 against the Reds but failed to drive in a run in the first five games, four of which the White Sox lost (it was a best-of-nine Series that year). Chicago won the sixth and seventh games, but fell behind quickly in the eighth contest. Jackson belted a homer, the only one of the Series, and drove in three runs in Game Eight, but his production came too late. Cincinnati defeated the favored White Sox by a 10-5 score and won its first World Series title. Jackson tied a record with his 12 hits in the Series, but eight of the 12 came during the four games the White Sox tried to win. In Chicago’s first four losses, Jackson went 4-for-16.

Before going home for the winter, Jackson went to Comiskey’s office in the ballpark and waited to see the Old Roman. Jackson wanted to tell Comiskey about the fix and possibly to return the money he had received. He stayed for several hours, but Comiskey holed up in his office and Jackson eventually left without talking to the White Sox owner.

In February 1920 team secretary Harry Grabiner traveled to Jackson’s home in Savannah and signed him to a substantial raise, a three-year deal for $8,000 per year. Jackson operated a successful poolroom there and a dry-cleaning business that employed more than 20 people. He and Katie used the money he had received for fixing the World Series to pay for his ill sister Gertrude’s hospital bills.

Despite the cloud of suspicion that hovered over him and several of his teammates. Jackson gave one of his finest performances in 1920, with a .382 average, a career-best 121 runs batted in, and a league-leading 20 triples. However, amid growing rumors that the White Sox were continuing to throw games in the 1920 season, Jackson felt alienated from most of the other Series conspirators. His evenings on the road consisted of going to the movies or bars with Lefty Williams, his best friend on the team.

With the White Sox fighting for a pennant entering the season’s final week, Jackson’s season ended abruptly on September 28, a day after a Philadelphia newspaper published allegations by gambler Billy Maharg claiming that eight members of the White Sox had helped him and other gamblers fix the World Series. Later that day, on the advice of White Sox team counsel Alfred Austrian, Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams appeared before a Cook County grand jury investigating the matter and testified about their involvement. Comiskey immediately suspended Jackson and the six other accused players who were still with the team.

Jackson’s appearance before the grand jury on September 28 was responsible for one of the most enduring legends in sports. As reported by Charley Owens of the Chicago Daily News, a small child is said to have looked at Jackson exiting the court building and begged, “Say it ain’t so, Joe.” Jackson and many others denied that the incident ever happened. “There wasn’t a bit of truth in it,” Jackson told reporter Furman Bisher in 1949. “When I came out of the building, this deputy asked me where I was going, and I told him to the South Side. … There was a big crowd hanging around the front of the building, but nobody else said anything to me. It just didn’t happen, that’s all. Charley Owens just made up a good story and wrote it.”19

Despite being acquitted by a trial jury, all eight accused players, including the retired Gandil, were eventually expelled from baseball for life by new Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. The scandal brought a sad and untimely end to Joe Jackson’s brilliant baseball career.

Jackson, whose lifetime batting average of .356 is the third highest in the game’s history, played semipro and “unorganized” ball, mostly in the South, for many years thereafter. Wherever he went, his cannon arm and effortless swing drew attention. In 1923 he signed with a team from Americus, Georgia, in the outlaw South Georgia League, and helped lead them to a championship. There was some controversy because the league did not want its younger players to be penalized or banned from Organized Baseball for playing with him. However, he batted well over .400, made incredible catches and throws, and drew large crowds throughout the season.

In 1923 Jackson hired a Milwaukee-based attorney, Ray Cannon, and sued the White Sox for back pay he felt was owed to him after his acquittal in the Black Sox trial. Joe believed that Harry Grabiner had taken advantage of his illiteracy in obtaining his signature on a contract that included the hated “reserve clause,” which effectively allowed teams to control their players in perpetuity. A jury sided with Jackson and awarded him more than $16,000 in back pay, but Jackson’s deposition about his involvement in the World Series scandal clashed so much with his 1920 grand jury testimony that the judge threw out the verdict and charged Jackson with perjury. Jackson settled with Comiskey for an undisclosed amount and went back home to Georgia.20

For the next several years, Jackson played ball in the South, where folks regarded him with kindness and still stood in awe of his ability. He sported a sizable paunch around his midsection, but he could still knock the stuffing out of a baseball until he was nearly 50 years old. He gave a few newspaper interviews in which he made his case for reinstatement, but mostly stayed out the public eye during the last three decades of his life.

“All the big sportswriters seemed to enjoy writing about me as an ignorant cotton-mill boy with nothing but lint where my brains ought to be,” Jackson said in 1949. “That was all right with me. I was able to fool a lot of pitchers and managers and club owners I wouldn’t have been able to fool if they’d thought I was smarter.”21

Jackson eventually moved back to his old neighborhood in Greenville, near the Brandon Mill textile factory, where he operated a successful restaurant and a liquor store for many years. He spent a great deal of time teaching baseball to the local youngsters and organizing impromptu games, even as he suffered from diabetes and liver and heart problems in his later years. In September 1951 Cleveland Indians fans honored him by voting him into the team’s Hall of Fame and, in the ensuing publicity blitz, Jackson agreed to travel to New York to appear on Ed Sullivan’s “Toast of the Town” television show. However, just two weeks before his scheduled appearance, Jackson suffered a heart attack and he died at home, at the age of 64, on December 5, 1951. He was buried in Woodlawn Memorial Park in Greenville.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Notes

1 Paul Dickson, Baseball’s Greatest Quotations (New York: Harper Perennial, 1992), 204.

2 Jackson’s date of birth has been recorded as 1887, 1888, and 1889 in different places. The family Bible was lost in a fire many years ago, but although Joe’s official death certificate lists his birth year as 1889, his tombstone lists his year of birth as 1888. As for his middle name, there is dispute whether it was Walker, Wofford, Jefferson, or some combination of the above. In 2015, SABR member Jimmy Keenan discovered multiple interviews in which Jackson claimed that “Walker” was his middle name. However, his death certificate and all other official documentation use the initial W. See the SABR Black Sox Scandal’s June 2016 newsletter for more discussion on this matter.

3 F.C. Lane, “The Man Who Might Have Been the Greatest Player in the Game,” Baseball Magazine, March 1916, 59.

4 Furman Bisher, “This Is the Truth,” Sport Magazine, October 1949.

5 Greenville News, August 17, 1908. Mack paid $1,500 for Jackson and outfielder/pitcher Scotty Barr. The Greenville newspaper reported that Jackson’s value was $900, though other sources differ on the breakdown.

6 Bisher, “This Is the Truth.”

7 Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 4, 1911.

8 Bisher, “This Is the Truth.”

9 Peter Golenbock, Fenway: An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox (New York: Putnam Publishing, 1992), 56.

10 Harvey Frommer, Shoeless Joe and Ragtime Baseball (Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1992), 41.

11 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 21, 1915.

12 The Sporting News, August 26, 1915.

13 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 21, 1915.

14 However, several minor leaguers had cleared 400 feet in earlier distance-throwing competitions. And in 1881, pitcher Tony Mullane had thrown a ball nearly 417 feet.

15 Chicago Daily News, May 3, 1918.

16 The Sporting News, June 20, 1918.

17 Bob Broeg, Superstars of Baseball (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1971), 38.

18 This is the explanation Joe Jackson gave in his testimony to the Cook County Grand Jury on September 28, 1920.

19 Bisher, “This Is the Truth.”

20 Chicago Herald-Examiner, February 16, 1924.

21 Bisher, “This Is the Truth.”

Full Name

Joseph W. Jackson

Born

July 16, 1887 at Pickens County, SC (USA)

Died

December 5, 1951 at Greenville, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.