Ben Geraghty

“He was the greatest manager I ever played for, perhaps the greatest manager who ever lived, and that includes managers in the big leagues. I’ve never played for a guy who could get more out of every ballplayer than he could. He knew how to communicate with everybody and to treat every player as an individual.”1 – Hank Aaron

Sad paradox defined Ben Geraghty. His brilliance in developing minor-league talent largely denied his ambition of becoming a big-league skipper. “He was a victim of ‘Catch-22’ logic,” wrote Pat Jordan, whose memoir A False Spring etched a poignant portrait of Geraghty.2

Sad paradox defined Ben Geraghty. His brilliance in developing minor-league talent largely denied his ambition of becoming a big-league skipper. “He was a victim of ‘Catch-22’ logic,” wrote Pat Jordan, whose memoir A False Spring etched a poignant portrait of Geraghty.2

In his playing days, Geraghty became one of the rare men to step off a college campus and go right to the majors. Yet the infielder played just 70 games at the top level, scattered widely over three seasons (1936, 1943, and 1944). Shortly before his death Geraghty said, “I knew, the first month I was up with Brooklyn, that I was not good enough to play this game. I made up my mind that if I was going to stay in baseball I’d have to do it with my head.”3

Geraghty was already viewed as managerial timber when he survived one of baseball’s most terrible accidents: the June 1946 bus crash in Washington state’s Snoqualmie Pass that killed nine of his teammates on the Spokane Indians and injured five others. In the disaster’s aftermath, he developed unusual psychological gifts, rooted in his trauma. “This deepened perception was what made Ben Geraghty a great manager and a great man,” Jordan wrote.4 But the cost was high. To remain a manager, he had to do what scared him most – continue to ride buses. To cope with his deep-seated fears, Geraghty constantly self-medicated with beer. Thus, his health was slowly ruined. A heart attack killed him in 1963, aged just 50.

Benjamin Raymond Geraghty was born on July 19, 1912, in Jersey City, New Jersey. His father was Patrick Geraghty, who was born in New Jersey after his parents emigrated from Ireland. The census for both 1900 and 1910 lists Patrick as a teamster; the 1920 census shows him more specifically as a chauffeur for a tea factory.

In 1894 Patrick married Ida Hines, whose father came from Ireland and whose mother was born in New Jersey. Over a 17-year period, the couple had eight children: John, Catherine, Helen, Thomas, Anna, James, Mary, and finally Benjamin.

As of the 1920 census, the family lived at 157 Grand Street in Jersey City. Also living in the same house was a family of four named Greaves; Ida’s two younger brothers, John and Peter; and a Swedish boarder. In the 1920s and 1930s, Grand Street was very close to the busy railroad yards on that side of the Hudson River. Today, it’s just a few blocks from the Exchange Place light-rail station.

The first available description of Geraghty is at age 15, when he attended St. Peter’s Preparatory School in Jersey City. This Jesuit school, which still operates today, is located at 144 Grand Street – across the street from the Geraghty home. At that time Ben was a pitcher, and one may infer that he was a late bloomer. The 1928 yearbook said, “‘Benny’ Geraghty, diminutive Freshman twirler, shows promise of future greatness.” Despite his lack of height, he was also a member of the basketball team.

Patrick Geraghty, aged 55, had died in August 1926 in an accident at work. Then working as night manager of the National Grocery Company garage in Jersey City, he was crushed between two five-ton trucks.5 Ben’s older brother Thomas became a surrogate father. The 1930 census shows Thomas (a policeman) as head of the Geraghty household. Ida, Catherine, Anna, James, and Mary were still under the same roof, along with Ben, his uncles John and Peter, and two lodgers.

In the fall of 1930, his junior year, Geraghty switched to another Catholic prep school, St. Benedict’s, in Newark. He graduated with the Class of 1932. His class yearbook said, “He is given to sports,” adding, “He plays a gilt-edged brand of football and baseball, but he is absolutely a ‘wiz’ on the basketball court. Ben’s friendly nature and lively spirit have paved the way for his popularity.”

With support from his brother Thomas, Geraghty went on to attend Villanova University, also a Catholic institution. There he played baseball and basketball. The coach of both squads in those years was George “Doc” Jacobs. When full-grown, Ben stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 170 pounds. He was above average height for an American man then (and now), but still small for his basketball position, forward. He was a good scorer, though, and became captain of the hoops team in his senior year, 1935-36.

On the diamond, Geraghty competed for the third-base job with Frank Skaff, who also played briefly in the majors (1935; 1943). Like Geraghty, Skaff went on to a long career managing in the minors – but he actually did become a big-league pilot, for part of the 1965 season with the Detroit Tigers.

Geraghty and Skaff both also played for the Berwyn team in the Main Line Baseball League, “one of the better semi-professional circuits in the [Philadelphia] area during the first half of the 20th century. Formed in 1904, it was also one of the earliest such leagues in the country.”6

In early 1936 Geraghty jumped to major-league baseball. He had attracted the attention of scout Mel Logan, who recommended him to the Brooklyn Dodgers.7 Originally, the invitation was for a look-see, but it quickly developed into more. A news snippet from the Associated Press that March said, “Ben Geraghty, who batted .379 with the Villanova varsity in 1935, is looking good in the short field for Casey Stengel of the Dodgers. He’s fast of head and hand and the boys don’t stray far off the bag when he’s on duty. Casey says the minors is no place for a guy like Geraghty.”8

The rookie’s big break came when Brooklyn’s incumbent shortstop, Lonny Frey, went out in mid-March with tonsillitis. Frey was also error-prone, having committed 44 the previous season. Geraghty kept up the good work. For example, St. Louis Cardinals manager Frankie Frisch said, “I made the jump from [Fordham University] to the big leagues without having to play in the minors, and maybe he’ll do it.”9

Indeed, the completely unseasoned Geraghty made Brooklyn’s Opening Day roster, beating out Johnny Hudson (Stengel moved Lonny Frey to second base). As a result, plans to return to Villanova to complete his degree in journalism were postponed until the fall.10

It’s also noteworthy that the press gave Geraghty’s age then as 21. For the rest of his life, this two-year difference was often visible in newspaper stories.

Jimmy Jordan started the first three games of the 1936 season at shortstop for Brooklyn, but Geraghty then got an extended trial, starting the next 15 straight. He held the position even after veteran third baseman Jersey Joe Stripp ended his holdout on April 21, which prompted talk of a shuffle, with Frey moving back to short.11 Geraghty was a singles hitter – he never hit a home run as a professional player, and he batted .262 during his minor-league career. However, he hit well to start with in the majors. In his first 10 games, he was 15-for-35 (.429).

Garrulous Casey Stengel raved at length about Geraghty’s eye at the plate, his range and arm in the field, his head, and his toughness. After the game of April 19, in which Phillies player-manager Jimmie Wilson kicked the ball out of the rookie’s glove on a stolen base, Geraghty told Stengel, “He won’t pull that again on me. The next time I’ll just take that throw and tag him on the nose with the ball.”12

On April 26, again playing Philadelphia, Geraghty reached base twice on catcher’s interference. It was the first of just six recorded instances of this in a single big-league game (as of 2015).13 The press portrayed it too as a case of “welcoming” newcomers – “Earl Grace, the Philly catcher, tipped his bat, unable to resist the temptation with a rookie player at bat and a rookie umpire working behind the plate.”14

In early May, however, Geraghty hurt his hand and missed five games. Upon his return, he went into a slump. Thereafter he was just a sporadic starter, and he wound up hitting .194 with four doubles and nine RBIs in 141 plate appearances. Near the end of July, Brooklyn farmed him out to Allentown in the NewYork-Penn League (Class A). By one account, he lost his batting eye after the May layoff. 15 By another, though, it was the classic story – the pitchers had figured him out after once around the league.16

Geraghty did not play at all during 1937. Two stories from 1943 said he was in an auto accident.17 There is clear evidence, though, that he sat out the season. The Dodgers placed Geraghty on their ineligible list when he refused to join Knoxville in the Southern Association after he had been assigned there in February.18 Meanwhile, he became superintendent of a cemetery.

In August 1937 the Dodgers dealt Geraghty to the Trenton Senators of the Eastern League (Class A). This farm club of the Washington Senators was owned by Joe Cambria, who became best known for cultivating Cuba as a source of players for Washington.19 Geraghty’s appeal to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for reinstatement was granted in December 1937.20

With Trenton in 1938, Geraghty hit .264 in 120 games. That November 17 he married Mary Dowd, from Livingston, New Jersey.21 They had five children. Four of them were sons: Patrick, Barry, Thomas, and Benjamin Jr. (“Benjie”). The one daughter, Elizabeth, was born after Pat.

In 1939 the Trenton franchise was transferred to Springfield, Massachusetts. It remained in the Eastern League, Joe Cambria was still the owner, and Washington was still the parent club.22 Geraghty hit .233 in just 36 games, apparently missing time with a broken elbow. 23 On July 28 he also collapsed from a hemorrhage after scoring from first base on a dropped pop fly, and was forced to leave the game. After the game, he was sold to the opposing club, Williamsport in the Philadelphia Athletics organization.24

Baseball-reference.com has an entry for Geraghty with Williamsport in 1940, but there are no statistics on that line. He did not play in 1941 or 1942 – in fact, The Sporting News did not mention him at all between November 1939 and April 1943. He reportedly returned to his cemetery job; then, after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he took a job in a California shipyard. There Geraghty remained until Casey Stengel, who had become manager of the Boston Braves in 1938, persuaded the “intelligent diamond operative” to head back East and try to make a comeback.25

The Braves held spring training in 1943 at The Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) in Wallingford, Connecticut. Three players, including Geraghty, suffered leg injuries that Stengel blamed on the soft and slippery surface of the indoor baseball cage. Taskmaster Stengel said, “From now on, regardless of how chilly it is, we’ll do most of our work outdoors.”26

After Geraghty became a manager, he cited this influence: “Stengel was very good with young players, and he believed in hard work in spring training. It sort of stuck with me, and the more I thought about it, the more I put it into effect and the better the results were. I made it one of my principles that if we work hard in the spring, we’ll have some easy days in July.”27

Geraghty was with the Braves until past the All-Star break, but he got into just eight games during May, June, and July. He appeared five times as a pinch-runner and came to the plate just once. On July 18 Boston optioned him to Hartford in the Eastern League, where he hit. .312 in 39 games.

It was a similar story in 1944: In 11 big-league games, Geraghty was 4-for-16 with a walk in 17 plate appearances. He played seven times for Boston during April and early May. He was then sent to Syracuse in the International League (Double-A), a Cincinnati Reds farm club. He hit .224-0-22 in 84 games. Returning to Boston in September, he made his last four appearances in the majors.

Geraghty was on the Boston roster to begin the 1945 season, but when the time came to cut down rosters in May, he had not appeared in a game. He was sent down to Indianapolis of the American Association (Double-A), where he hit .270-0-25 in 117 games.

Before of the 1946 season, Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League obtained Geraghty, but he appeared just four times for the Solons before he was released. He then signed with the Spokane Indians of the Western International League (Class B). According to Geraghty’s obituary in The Sporting News, as well as Hank Aaron, he was brought in with an eye to replacing Mel Cole as manager. Cole had taken over from former big-league star Glenn Wright, who was released just before the start of the season. The obit held that Geraghty’s arrival sparked a winning streak, though, and so Cole kept his job.28

The fateful crash of the Spokane team bus on June 24, 1946, has been chronicled in depth. The Spokane Spokesman-Review devoted full-length features to the event in 1971, 1986, and 1996.29 For this story, the focus is on Geraghty, who was sitting near the back. As the bus broke through the guard cables and tumbled 350 feet, he was thrown clear. “You know those aluminum frames around bus windows?” he said the next day. “I shot out as we rolled downhill and when I stopped rolling I was wearing a frame on my neck. I looked down at the bus, a hundred feet below. It was burning. I felt like hell.”30

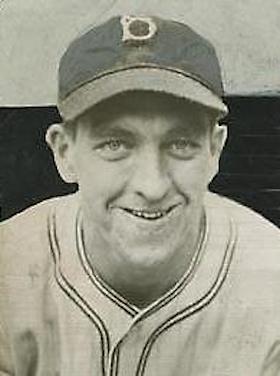

From left, Joe Faria, Pete Barisoff, Ben Geraghty, and Milt Cadinha in Oakland Oaks uniforms. (Courtesy of David Eskenazi Collection)

Geraghty suffered a broken kneecap and a V-shaped cut on his head that took 28 stitches. Since Cole was one of those killed, Geraghty – on crutches, with scalp bandaged – was named the manager.31 He was unable to fulfill his new duties, though, and was restricted on doctor’s orders. As a result, Glenn Wright was brought back.32 The Indians resumed play on July 4 with a makeshift roster featuring players on loan from other teams.

Geraghty was at last named Spokane’s manager in February 1947. He believed that his broken kneecap had healed and he intended to play second base again.33 He appeared in 31 games in 1947 as a player. In a neck-and-neck race, the Indians finished in second place, with a winning percentage .001 behind Vancouver, which played two fewer games.

Spokane had a working agreement with the Brooklyn Dodgers that year. According to Spokane sportswriter Bob Johnson, Geraghty got on the bad side of Brooklyn’s general manager, Branch Rickey, and club owner Sam Collins by criticizing the release of an outfield prospect. Johnson said that Rickey and Collins would have fired Geraghty except that the manager was “pretty solid with a lot of fans.”34

In October 1947 Collins sold the Spokane club and released Geraghty. The Boston Braves, Boston Red Sox, and Detroit Tigers all made overtures to Geraghty to join their organization, but the proposition that interested him most came from the Cleveland Indians.35

To start the 1948 season, Geraghty managed Cleveland’s Meridian (Mississippi) affiliate in the Southeastern League (Class B). One of his opposite numbers was Frank Skaff, then at the helm of the Montgomery Rebels. (They also faced each other as managers during the 1957 season in the American Association.) Geraghty appeared in 15 games as a player for Meridian, his last on-field action. On May 30 he was relieved of his duties.36 In July he went to Palatka in the Florida State League (Class D) because the manager there had resigned.37 Palatka finished in eighth place.

Geraghty then moved to the New York Giants organization. In 1949 and 1950 he managed Bristol (Virginia) of the Appalachian League. It was then a Class D circuit, and Geraghty received no coverage in The Sporting News. The Twins finished third in 1949 and second in 1950.

In 1951 the Giants assigned Geraghty to manage the Jacksonville Tars in the South Atlantic League (Class A). On April 4 the Tars upset the Red Sox – starring Ted Williams – in an exhibition game, 8-7. The league’s sportswriters viewed Geraghty highly; in August, one report said, “A great deal of the Tar success this season must be attributed to Ben Geraghty, who, with his magic touch, has turned a poor spring team into a 1951 pennant contender for the first time in years.”38

Jacksonville wound up in second place that year, but slipped to seventh in 1952. The Tars’ .448 winning percentage was the worst that a Geraghty team posted over a full season. The Giants did not renew their pact with Jacksonville after the ’52 season. During January and February 1953, Geraghty served as an instructor in the St. Augustine baseball school owned by New York Yankees pitcher Eddie Lopat.39

In 1953 Jacksonville became an affiliate of the Milwaukee Braves, and the Tars also became known as the Braves. The club won the South Atlantic League pennant with a .679 winning percentage (93-44). Geraghty, who had been persuaded to leave the Giants chain, was named the Sally League’s top manager.40 His big star was 19-year-old Hank Aaron, in his second and last year in the minors. As the quote introducing this story shows, Geraghty had a profound influence on Aaron. In 1972 the slugger said, “He chewed me out when I needed it, but he told me how good I could be and – most important – he taught me how to study the game, and never make the same mistake twice. I know how badly he wanted to manage in the big leagues, so I know how much it hurt when he didn’t get the job.”41

As author Charlie Vascellaro wrote in his biography of Aaron, “Geraghty was also constantly on Aaron’s side and made a point of spending time with the black players wherever their separate accommodations would have them on the road. Whether it was a boarding house or blacks-only hotel, Geraghty would stop by in the evenings after games to knock back a few beers and talk baseball, his two favorite things. It made Aaron, [Horace] Garner, and [Felix] Mantilla feel appreciated as part of the team. Aaron recalled a night in Columbus when the team was invited to dinner at Fort Benning and the black players were told they were not allowed to eat in the dining room – Geraghty joined them for the meal in the kitchen.”42 Pat Jordan also recounted how Geraghty loudly demanded that the players of color be served at restaurants, and how he would not quit until he found one that would relent.43

Geraghty thought Black players were good for the business of baseball too. After the 1953 season ended, he said, “Negro players have been our salvation from a financial standpoint. They’ve doubled our attendance. When we started hiring Negro players we found our ball park was just not big enough for the crowd, no matter what time the game was scheduled. Managers of other teams we played all said the same – by playing us they were certain to double their regular attendance.” That story also noted Geraghty’s offseason job then, selling television sets.44

Geraghty spent three more summers in Single-A ball. Jacksonville finished first again in 1954, second in 1955 after folding down the stretch, and returned to the top in 1956. A 1955 story underscored his emphasis on the mental aspect of the game. “A guy who doesn’t study to improve himself has got no place in baseball. We got enough rockheads already.”45

In the winter of 1954-55, Geraghty managed in Latin America for the first time. He led the Caguas-Guayama Criollos of the Puerto Rican Winter League. It came about just 10 days before the season started, when incumbent manager Mickey Owen, who had been expected to return, signed instead to play in Venezuela.46 The Braves had an unofficial working agreement with this team, and many of their prospects – from both the United States and Puerto Rico – developed there under Geraghty’s tutelage.

Geraghty’s second season in the PRWL, 1955-56, was most notable. At the end of the season, he and Herman Franks, skipper of the Santurce Crabbers, each received 14 votes for Manager of the Year. Yet even though the Crabbers had finished first in the regular season, Franks asked that his rival be given the honor.47 Caguas-Guayama won the league championship that year, defeating Santurce in the finals. It was Geraghty’s only title in winter ball.

The Criollos then moved on to represent Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Series, a round-robin tournament featuring the region’s four main winter-league champions. Geraghty’s squad – starring local hero Vic Power and blue-chip Braves prospect Wes Covington – finished tied for second with a 3-3 record.

In June 1956 Milwaukee fired manager Charlie Grimm. Coach Fred Haney replaced him, and the Braves went on an 11-game winning streak. Haney was hired for the 1957 season on September 11. Geraghty was not mentioned in the press as a candidate at that point, though in 1961 he called it the first time that Milwaukee passed him over for the job.48

Shortly after the 1956 season ended, Connie Ryan was named to manage Milwaukee’s top farm club, Wichita in the American Association. Instead, that December Ryan became third-base coach with the big club, and the Triple-A job went to Geraghty, who got the news while managing in Caguas (a team that included Sandy Koufax for part of the season).49 Already the “flint-faced worry-wart” was on record with his ambition to manage in the majors.50

Wichita, which had finished in seventh place the year before, brought up its game in 1957 with substantially the same roster. “Look at what Ben Geraghty’s done to that club,” was a frequent remark early that season, and the difference was attributed to attitude.51 The team went on to win the American Association pennant despite a rash of injuries and even though Milwaukee called up several of the team’s key players while fighting for the National League pennant.52 Geraghty held the parent club’s interests higher, though – as seen in his crucial recommendation of Bob “Hurricane” Hazle to general manager John Quinn.53

Geraghty was a superstitious man. That summer he got his wife to dig an old rabbit’s foot out of a trunk at home, and “we won eight straight games after I hung the rabbit’s foot in my locker. Several of the games were downright lucky and something had to be responsible for the victories.” The connection in his mind was further cemented when the winning streak ended after Geraghty forgot to take the talisman with him. The team won again after TWA rushed it from Wichita to Indianapolis.54

These beliefs were most pronounced in wearing his “lucky shirt” on bus rides, during which he would consume a case of beer and talk incessantly to the driver to ease his extreme tension.55 “He had an amazing capacity for beer,” Hank Aaron later wrote. “It did seem to keep one brewery busy to keep Ben supplied with beer. The unusual thing about him, though, was that he never seemed to show the effects of it at all.”56

That season also provided a couple of other insights into the manager’s philosophy. “Hustle is contagious,” he said. He also sought to get his teams 20 games over .500 early on. “Once you get the 20-cushion, you can play around .500 ball the rest of the season and it takes an awfully hot club to beat you.”57

Although Milwaukee won the World Series in 1957, Haney was reportedly on the hot seat at one point. A June 1958 story about pitcher Juan Pizarro, then with Wichita, said “Geraghty … some day may be the director of Milwaukee strategy and was mentioned as a replacement for Fred Haney last year when the Braves were slumping.”58

Geraghty’s name also surfaced as a potential replacement for Connie Ryan after Ryan (along with fellow coaches Charlie Root and Johnny Riddle) was fired just 17 days after Milwaukee won its championship.59 “If Ben wants the job, the chances are he can have it,” wrote Lloyd Larson of the Milwaukee Sentinel.60 Instead, Billy Herman replaced Ryan, and Geraghty stayed in Wichita.

When that story broke, Geraghty was in winter ball – but in a different country, the Dominican Republic. He led Estrellas Orientales, a team that (like Caguas) featured many players from the Braves organization.61 November brought the news that the American Association’s sportswriters had unanimously chosen Geraghty as the league’s manager of the year.62 A broader honor from The Sporting News as Minor League Manager of the Year followed at the beginning of 1958.63

Wichita finished second in 1958. After a slow start, Geraghty got his team back near the top, but this time he could not overcome the loss of talent to the parent club. After that season, Geraghty and his family moved to the Milwaukee suburb of Brookfield. He returned to manage Caguas in the winter of 1958-59, but the old infielder hurt his knee in January while demonstrating how to turn a double play. After that, he was hit by a line foul while watching batting practice. Geraghty returned to Milwaukee for treatment, and Vic Power filled in for him.64 That was the last time Geraghty managed in Latin America.

The Wichita franchise was switched to Louisville in November 1958. Geraghty remained as manager in the new location, and he was again successful in 1959, leading the Colonels to the American Association pennant. They lost in the first round of the playoffs, however, as Wichita had in both 1957 and 1958. Observations of Geraghty from this season are visible in A Baseball Odyssey, the 1999 memoir by globetrotting Panamanian player Dave Roberts. Roberts noted that Geraghty was the most respected manager in the Milwaukee system. He also alluded to Geraghty’s drinking problem (which, according to Pat Jordan, led to liver disease).

During the World Series in 1959, Fred Haney resigned as Milwaukee’s manager. Straight away, the Associated Press put forth a lengthy list of candidates, headed by Leo Durocher and Red Schoendienst. The article said, “Ben Geraghty … was ruled out because he is no name manager and lacks big league managerial experience.”65 Again Catch-22 logic was visible.

The race was still open, though. On October 10 Lou Chapman of the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote, “Ben Geraghty, the Louisville manager who has done nothing but win, is a sentimental favorite among members of the press corps. The writers insist that he is the logical choice; that he is an excellent baseball man and should by merit get the job. But the brass reportedly is looking for a ‘glamor’ boy – a strong man.”66 Allegedly the field had been trimmed to four at that point, excluding Geraghty. Yet less than two weeks later, Lloyd Larson called it a “guessing sweepstakes” and mentioned that Geraghty was still a possibility.67

On October 23 the Braves hired Charlie Dressen to replace Haney. At the end of the month, Geraghty re-signed to manage Louisville in 1960. Publicly, he was gracious about how it had turned out. “I think Dressen coming into our organization will mean a big difference to our personnel in Milwaukee. The boys will be better off,” he said in January. That story by United Press International led by describing him as “the guy many call the best manager in minor league baseball.”68

During the fall of 1959, Geraghty went to Bradenton, Florida, to work with Braves prospects in the Instructional League. After the new year came, he supervised a program of drills ahead of spring training for players living in the Milwaukee area. He said of the idea, which general manager John McHale sponsored, “This could do the boys a lot of good. … They can accomplish more working together like this than on their own at some gymnasium. Otherwise, people hang around and talk to them and they kill a lot of time.”69

Soon thereafter, as he had done in the past, Geraghty went to the Braves’ training camp in Bradenton. He was a member of Charlie Dressen’s board of strategy. After returning to Louisville, that May Geraghty was hospitalized with an ulcer condition.70 Stomach troubles were not something new; an attack of nervous indigestion had sidelined him for several days in June 1955.71 Doctors ordered six months of rest, which sidelined him for the rest of the summer campaign.

By early August, though, Geraghty was cleared to instruct young men from the Milwaukee area aged 16 to 21 in a baseball clinic.72 A couple of weeks later, he vowed to return to the dugout, saying “I feel better and younger than I have in years. … I feel like I’m closer than ever to my goal of being a major league manager. When my chance in the majors comes, I’ll be ready.”73

In the fall of 1960, Geraghty returned to Bradenton and the Instructional League. It was here that Pat Jordan (then still a pitcher of promise) first encountered the revered manager, whose extraordinary reputation preceded him. Jordan devoted more than 10 pages of A False Spring to Geraghty’s story. The multi-faceted depiction covered the manager’s unwell appearance, inner stress, and weakened health – and its flip side, even more enhanced mental focus and unmatched motivational skills. In awe, Jordan wasn’t sure at first whether Geraghty was “a saint or a madman.” Eventually, the author came to view his manager as “more saint than evangelist,” a man who made a “compulsive sacrifice” on behalf of his players.74

Before the 1961 season, Geraghty told the Toledo Blade directly, “My Milwaukee bosses believe I am too valuable in training and developing young players. At least that’s the reason I have been told why I have not moved up to at least a coaching job with the Braves. However, I would rather manage in the minors than coach in the majors.”75 He remained in Louisville, leading the Colonels to a second-place finish in the regular season. The team won the playoffs and advanced to the Junior World Series, where they were swept by the Buffalo Bisons.

Meanwhile, in early September 1961, Milwaukee fired Charlie Dressen with 25 games left in the season. Replacing Dressen was Birdie Tebbetts, who stepped down from the front office. Tebbetts expressed a desire to be closer to “the things I love most”; John McHale said that Tebbetts had made himself available to owner Lou Perini a couple of weeks before and that “Mr. Perini has been trying to hire Birdie since 1946.”76

After being passed over for the third time, Geraghty had had enough of the Milwaukee organization. He felt that he was held back, despite his record of success, and asked McHale for his release. Geraghty said the GM talked to him on the telephone for 32 minutes trying to keep him, even volunteering to fly down for further talks in person. “But all the Braves wanted me for was to stay in the minors and develop younger players,” Geraghty declared.77

Geraghty’s value as “polisher of diamonds in the rough” (as one story put it that April) was undoubted.78 One may speculate, though, about what else John McHale may have been thinking. McHale was pragmatic – he may have been concerned that Geraghty’s health was a risk – yet the executive was also a very compassionate man. It couldn’t have been easy for him.

Meanwhile, a fresh opportunity for Geraghty had arisen. He returned to Jacksonville, where Cuban baseball man Bobby Maduro had just obtained territorial rights at the beginning of October. Maduro’s Havana Cubans had been compelled to move to Jersey City in July 1960, but the franchise failed there. The International League dropped the location and replaced it with Jacksonville. Maduro, who served as his own general manager, established a working agreement with the Cleveland Indians. Local baseball fans were said to want Geraghty back to take the reins of the new club.79

On October 11 Geraghty signed a three-year contract, calling it “an offer no one could afford to turn down. I hated to leave the Milwaukee system, but this is the second turning point in my baseball career. The first was when I worked for Mr. Wolfson in the mid ’50s.” 80 Sam Wolfson was a prominent local businessman who had bought the Jacksonville Tars after the 1952 season. He helped persuade Maduro to come to Jacksonville; Wolfson then became president of the new franchise, the Suns.81 He claimed that Geraghty had become the highest-paid manager in the minor leagues.82

Another factor that could have influenced Geraghty’s decision was the unstable managing situation in Cleveland. In August 1960 an unusual trade of skippers – Joe Gordon for Jimmie Dykes – took place between the Indians and Detroit Tigers. Well before the end of the 1961 season, there were rumors that Dykes was on the way out. As it developed, his replacement for 1962, Mel McGaha, was also fired just before the season ended. When McGaha got the job, the Toledo Blade noted, “Managing the Indians is no easy assignment.”83

A few months later, Geraghty had to deal with another health problem. On January 29, 1962, he underwent a four-hour operation to correct a circulatory ailment. He spent approximately two weeks in the hospital recovering, but was ready for spring training.84

Geraghty, a noted after-dinner speaker, was hugely popular in Jacksonville. The city held Ben Geraghty Night on July 21, 1962, showering him with gifts.85 He burnished his image further because the Suns finished first in the International League during the regular season, with a record of 94-60. They held the lead for all but two days.86 However, they lost to the Atlanta Crackers (a team that got hot late in the year) in the seventh game of the International League playoff finals. The Sporting News named Geraghty Minor League Manager of the Year for the second time.

“You’ve got to be lucky in this game to win,” was Geraghty’s modest remark upon receiving the award. “Nobody could have expected Vic Davalillo and Tony Martinez to have the years they enjoyed.”87 Yet The Sporting News cited his ongoing work in player development. In the editorial saluting its Men of the Year, the paper also noted, “These man, we are sure, prize their awards because they know better than anyone else the job they had to do to merit them.”88

In the fall of 1962, rumors were swirling that Lou Perini would sell the Braves. One said a Milwaukee brewing concern had asked Perini to name his price, and added that if the deal went through, supposedly John Quinn (then with the Phillies) would return as GM and Geraghty would at last get his shot as field boss.89 Instead, the following month Perini sold a 90 percent stake in the club to a syndicate that included John McHale. The new regime replaced Birdie Tebbetts – who, ironically, had taken an offer to become Cleveland’s manager – with Bobby Bragan.

It’s tempting to believe that if the Milwaukee job had at last become available, Maduro and Wolfson would have been sympathetic and released Geraghty from his contract. Wolfson, suffering from bone cancer, which ended his life the following August, resigned in late 1962.90

Instead, Geraghty returned for a second year at Jacksonville. The Suns started very slowly, something most unusual for a team of his. As of Monday, June 17, 1963 – which he spent at the beach with his wife – the club’s record stood at 26-39. Yet Geraghty and Maduro had not given up hope. “We still planned to make a fight for the pennant,” said Maduro, “and Monday night we discussed players we might obtain.”91

That same evening, though, Geraghty suffered pains in both shoulders – a warning signal of cardiac arrest. Though he reportedly had no known history of heart trouble, he had another major risk factor: he was a chain smoker. In the small hours of Tuesday morning, he awoke with pains in his chest. Mary called for medical help, but Ben Geraghty died at 4:15 A.M., before the physician arrived.92

Wire-service reports described Geraghty’s death as “totally unexpected … a shock to his family, friends, and fans.”93 That’s at odds with Pat Jordan’s depiction of Geraghty as a man acutely aware of his own mortality, “that his life was not spinning out at any natural speed, but that it was more like a 45-rpm record turning at a 78-rpm’s.”94 Of course, Jordan was writing in the early 1970s with the benefit of hindsight.

The Suns’ Tuesday night game at Jacksonville was played as scheduled, but Maduro canceled the pregame entertainment. 95 “I don’t know of another manager in baseball whom the paying fans held in so much respect,” wrote Bill Kastelz, sports editor of Jacksonville’s Florida Times-Union. “To those of us accustomed to seeing Number 36, cap visor pulled low over his forehead, Irish jaw at a belligerent angle, left hand jammed in his hip pocket, it’s going to take a little time to realize he’s gone.”96

Old friend Casey Stengel, who by then was managing the New York Mets, said, “[Geraghty’s] record was amazing. … (H)e was a completely dedicated man.”97 Indeed, in December 1958 Geraghty offered this credo for his success as a minor-league manager:

“Work and more work. … It’s getting the most out of a player. But to get it you have to delve into their backgrounds, live their lives with them, and then work on their weaknesses, whether they be mental or physical.”98

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published in March 2015. It was updated on January 29, 2021 with input from Mike and Ray Geraghty, great-nephew and nephew of Ben Geraghty.

Continued thanks to Eric Costello and to SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado for additional research. Thanks also to Mary Hauck, alumni and donor relations officer, St. Benedict’s Preparatory School.

Photo Credit

Geraghty with Spokane Indians teammates, 1946: David Eskenazi Collection.

Sources

Books

Crescioni Benítez, José A. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Internet

baseball-reference.com.

retrosheet.org.

ancestry.com.

fultonhistory.com.

Notes

1 Joel H. Cohen, Hammerin’ Hank of the Braves (New York: Scholastic Book Services, 1971), 32.

2 Pat Jordan, A False Spring (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1975). Page numbers drawn from 2005 paperback edition, (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press), 198.

3 Jack Mann, “Henry Aaron: Bad Man with a Bat,” Boys’ Life, March 1972, 11.

4 Jordan, A False Spring, 203.

5 “Killed by Trucks,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, August 4, 1926: 13. One of the trucks had stalled. Geraghty, using another truck, towed the “dead” machine until the motor started. In attempting to loosen the tow chain, the rear truck plunged forward and pinned him to the forward truck, killing Geraghty instantly. This story was found thanks to a description of the accident in telephone interviews with Mike and Ray Geraghty, January 28, 19221.

6 “Five Big League Ball Players Who Played for Berwyn,” History Quarterly, Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society, Volume 24, Number 3, July 1986, 111-119.

7 “Dodger Camp Really School,” New York Post, March 30, 1936, 1.

8 “Villanova Lad Stars with Brooklyn,” Associated Press, March 14, 1936.

9 “Frisch Likes Robins’ Rook,” NEA Service, April 18, 1936.

10 “Geraghty, Villanova Boy, Signed by Brooklyn Club,” Associated Press, March 31, 1935.

11 “Stripp to Play With Brooklyn,” United Press, April 22, 1936.

12 Jerry Mitchell, “Stengel Pops Off Plenty on Geraghty Skill,” New York Post, April 20, 1936, 15.

13 The others: Pat Corrales, twice (8/15/1965 and 9/29/1965), Dan Meyer (5/3/1977), Bob Stinson (7/24/1978), and David Murphy (4/11/2010). “Catcher’s Interference Twice in a Game,” Associated Press, April 14, 2010.

14 Jerry Mitchell, “Dodger Looks Calmly at Jurges Since Geraghty’s Local Boy, Too,” New York Post, April 27, 1936.

15 “Mungo to Move,” Associated Press, July 30, 1936.

16 James J. Murphy, “Geraghty, Hudson and Winston Farmed by Dodgers to Knoxville,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 12, 1937, 1.

17 Howell Stevens, “Stengel’s Braves Lean Strongly to Hill Side,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1943, 2; “Brave Rookie,” Spartanburg (South Carolina) Herald-Journal, April 21, 1943, 9.

18 “Ben Geraghty Reinstated,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 20, 1937, 1.

19 Harry O’Donnell, “Gilvary May Quit Baseball Permanently,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, August 6, 1937, 20.

20 “Ben Geraghty Reinstated.”

21 “Mary Dowd Church Bride,” New York Times, November 17, 1938, 22.

22 V.N. Wall, “Springfield, Mass. Gets Final O.K. from Cambria,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1939, 1.

23 “Brave Rookie.”

24 “Eastern League,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1939, 9.

25 Stevens, “Stengel’s Braves Lean Strongly to Hill Side.”

26 “Three Braves Rookies Have Minor Mishaps; Team to Work Outdoors,” Associated Press, April 1, 1943.

27 Randy Linthurst, “Too Good in Minors to Manage in Majors!” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, 1986. Original citation not available.

28 “Geraghty, Minors’ Standout Pilot, Dead of Heart Attack,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1963, 36; Henry Aaron with Furman Bisher, Aaron (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1974), 160 (originally published in 1968).

29 Mike Lynch and Alden Cross, “Baseball’s Darkest Night,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 20, 1971, Sunday Magazine-36; Jim Price, “Forty years later, ex-Indians look back on Spokane’s worst sports tragedy,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 22, 1986, Sports-1; Jim Price, “A Half-Century of Pain,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, June 24, 1996 (Price received the Macmillan-SABR Baseball Research Award for this story).

30 “Baseball Bus Death Toll Reaches Eight,” Associated Press, June 26, 1946.

31 Gail Fowler, “Spokane Still Ball-Minded After Tragedy,” Associated Press, June 28, 1946.

32 “Geraghty Ordered to Bench; Wright Is Temporary Pilot,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, July 2, 1946, 13.

33 “Spokane Names Ben Geraghty,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1947, 24.

34 Bob Johnson, “Honor for an Old Friend,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, January 1, 1963, 21.

35 Bob Johnson, “Ben Geraghty, Ex-Spokane Baseball Manager, Offered Job by Cleveland,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, December 25, 1947, 25.

36 Alvin Burt, “Three-B Plan Keeps Ben Geraghty on Top,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1955.

37 “Hurls No-Hitter, Six Days Later Resigns as Manager,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1948, 35.

38 George W. Booker, “Spring Triumph Over Red Sox Spurred Tars Into Flag Fight,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1951, 39.

39 Frank Eck, “Lopat Backs Salary Pitch by Pointing to Speedy Finish in ’52,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1953.

40 Red Thisted, “Braves in Balance at Home, Away,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1954.

41 Mann, “Henry Aaron: Bad Man with a Bat,” 11.

42 Charlie Vascellaro, Hank Aaron: A Biography (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 41.

43 Jordan, A False Spring, 196.

44 “Ex-Spokane Baseball Pilot All Out for Negro Stars,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, October 2, 1953, 15.

45 Burt, “Three-B Plan Keeps Ben Geraghty on Top.”

46 Pito Alvarez de la Vega, “Schultz, Craft Back as Pilots in Puerto Rico,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1954, 26.

47 Pito Alvarez de la Vega, “Rain Delays Puerto Rico Playoff Set,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1956, 28.

48 “Geraghty Sees New Chance at Jacksonville,” Associated Press, October 12, 1961.

49 Bob Wolf, “Connie Ryan Signs as a Braves Coach,” Milwaukee Journal, December 6, 1956, 20.

50 Joe Livingston, “Geraghty Jacksonville Manager 7th Time – On Record as Winner,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1956.

51 Frank Haraway, “Geraghty’s Magic Hailed at Wichita,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1957, 33.

52 “Ben Proved Leadership,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1958, 2.

53 Aaron, Aaron, 94.

54 Lloyd Larson, “Superstitious? Shake Hands with Lodge Brother Geraghty,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 24, 1957, Part 2, Page 3; “Rabbit’s Foot Wichita Luck Charm – Geraghty Proves It,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1957, 30.

55 Jordan, A False Spring, 203-204.

56 Aaron, Aaron, 161.

57 Frank Haraway, “Braves’ Flag Bid Turns Into Breeze,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1957, 37.

58 “Juan Pizarro Is a Man of Many Talents on the Baseball Diamond,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 31, 1958, 28.

59 “Braves Fire Three in Coaching Staff Shakeup,” Associated Press, October 28, 1957.

60 Lloyd Larson, “Geraghty Likely Choice as Coach,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 29, 1957, Part 2, Page 3.

61 Feliz Acosta Núñez, “Three Clubs in Dominican Loop to Have New Managers,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1957; Bob Wolf, “Braves Still Active,” Milwaukee Journal, October 31, 1957, 20.

62 “Geraghty Voted A.A. Pilot of ’57,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1957, 27.

63 Bob Burnes, “Ted, Lane, Hutch Majors’ Top Men,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1958.

64 Bob Wolf, “Braves’ Mantilla Is Flashing Fancy Keystone Capers,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1959, 16.

65 “Haney Bounced by Milwaukee,” Associated Press, October 5, 1959.

66 Lou Chapman, “‘Hutch’ First in Line to Pilot Braves,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 10, 1959, Part 2, Page 2.

67 Lloyd Larson, “Braves Managerial Guessing Sweepstakes in Full Swing,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 21, 1959, Part 1, Page 19.

68 “Ex-Spokane Pilot Still Is Waiting,” United Press International, January 7, 1960.

69 Bob Wolf, “Confident Covington Springs into Action, Ankle Good as New,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1960, 14.

70 “Geraghty Hospitalized,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 6, 1960, Part 2, Page 5.

71 “Rebels Snap Braves’ Streak,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1955, 33.

72 “Geraghty Added as Sluggers’ Instructor,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 31, 1960, Sports-6.

73 “I’ll Be Back in ’61 – Geraghty,” United Press International, August 16, 1960.

74 Jordan, A False Spring, 195-198; 200-206. Note that Jordan gave Geraghty’s age as 45 in 1960 and 48 at death.

75 Tom Bolger, “He’s Best in Minors – but Ignored,” Toledo Blade, March 26, 1961, Section 3, Page 2.

76 “Dressen Gets Ax; Tebbetts Named,” Associated Press, September 3, 1961.

77 “Geraghty Sees New Chance at Jacksonville,” Associated Press, October 12, 1961.

78 Bob Lassanske, “Botz Could Make It,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 15, 1961, Sports-7.

79 Bob Price, Jacksonville Replaces J.C. in Int League,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1961, 25.

80 Bob Price, “Geraghty Signs as New Skipper at Jacksonville,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1961, 25.

81 Joe Livingston, “Jacksonville Owner Pulls All Stops to Keep Club Winning,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1956, 14; “Wolfson, Jacksonville Club Official, Industrialist, Dead,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963, 38.

82 Price, “Geraghty Signs as New Skipper at Jacksonville”

83 Tom Bolger, “McGaha Sure Bet as Tribe’s New Boss,” Toledo Blade, September 27, 1961, 53.

84 “Geraghty Has Surgery,” Associated Press, January 29, 1962.

85 “Ben Geraghty Feted,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1962, 38.

86 Bob Price, “‘Misfit’ Suns Burn Up Int in Bow as Triple-A Entry,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1962, 31.

87 Clifford Kachline, “Geraghty Also Cited in ’57 – Won Six Flags in Ten Years,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1962, 4.

88 “Salute to ’62 Men of the Year,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1962, 10.

89 “Diamond Facts and Facets,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1962, 14.

90 “Wolfson Park timeline,” Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), September 3, 2002.

91 “Geraghty, Top Pilot, Dies at 50,” United Press International, June 19, 1963.

92 “Geraghty, Top Pilot, Dies at 50”; “Manager Ben Geraghty Dies.” Description of smoking habit comes from the memoirs of opposing manager Charlie Metro, Safe by a Mile (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 171.

93 “Geraghty, Top Pilot, Dies at 50”; “Manager Ben Geraghty Dies.”

94 Jordan, A False Spring, 204.

95“Manager Ben Geraghty Dies.”

96 Bill Foley, “Jacksonville baseball legend’s season ends short,” Florida Times-Union, June 19, 1963. This article was published on the 36th anniversary of the original story by Bill Kastelz.

97 “Geraghty, Top Pilot, Dies at 50.”

98 Bob Lassanske, “Geraghty Develops Acorns into Mighty Brave Oaks,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 28, 1958, 2-C.

Full Name

Benjamin Raymond Geraghty

Born

July 19, 1912 at Jersey City, NJ (USA)

Died

June 18, 1963 at Jacksonville, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.