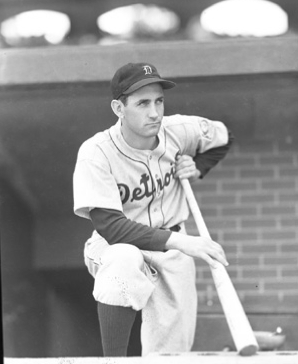

Charlie Gehringer

You wind him up in the spring and he goes all summer. He hits .330 or .340 or whatever, and then you shut him off in the fall. – Yankees Hall of Fame pitcher Lefty Gomez1

Charlie Gehringer was a model of consistency throughout his major-league career with the Detroit Tigers. This Hall of Fame second baseman finished with a career average of .320, failing to hit .300 in only three of his 16 full seasons. His quiet demeanor and modesty were noted by contemporaries, as was his grace in the infield.

Charlie Gehringer was a model of consistency throughout his major-league career with the Detroit Tigers. This Hall of Fame second baseman finished with a career average of .320, failing to hit .300 in only three of his 16 full seasons. His quiet demeanor and modesty were noted by contemporaries, as was his grace in the infield.

Charles Leonard Gehringer was born on a farm in Iosco Township, Livingston County, Michigan, on May 11, 1903. (Livingston County is midway between Detroit and Lansing.) He was the third of four children (and second son) of Theresa and Leonard Gehringer, who were both born in Germany; he also had seven step-siblings from his father’s first marriage and one from his mother’s.2 The family moved to the Ed Angel farm, just south of Fowlerville in Livingston County, when he was young.3 Young Charlie did not like farm work.

“It was a dairy and grain farm; we raised corn, oats, wheat, barley – everything,” he said in an interview in the 1980s. “It seemed that I had all the hard jobs – the weeding, shocking up the wheat, digging potatoes – mostly the hand work. Milking cows was the hardest, especially early in the morning.”4

Baseball was different – from the start.

“I think it was Lefty Gomez of the Yankees who gave me the ‘Mechanical Man’ name,” he told an interviewer. “He made a statement to the papers once that ‘you wind Gehringer up in the spring and turn him off in the fall and in between he hits .340.’ Unfortunately, it’s not quite that easy. Like anything, it’s a lot of hard work and practice.”5

Charlie often played with older boys and held his own. “I just kept working at it every chance I got,” he remembered.6 He played infield and pitched for Fowlerville High and lost only one game in three years.7 The baseball complex is now called Gehringer Field.8

His parents did not share his passion for baseball. “My father generally accepted it, but my mother heartily disapproved,” he recalled. “Every time I wanted to go off and play a high-school or sandlot game, there’d be a battle. She got to be a great fan eventually, but it was hard going for a long while. My father died in the middle of my first year in professional ball, and never saw me play except in high school or at the fairgrounds.”9

By 1922, besides his older brother, who handled the tough farm work, his parents had a hired man, freeing Charlie to leave the farm for the University of Michigan to study physical education.10 He earned a freshman letter in baseball11 and worked part-time in an ice-cream plant. By then he had graduated from the Fowlerville town team to an independent team in Angola, Indiana.12

Gehringer’s chance to leave the farm permanently came in the fall of 1923. A local man who hunted with Bobby Veach told the former Tigers outfielder about Charlie and arranged for a tryout in Detroit.

“Ty Cobb was the manager then, and apparently he was so impressed he went up in his uniform to Mr. Navin, the club owner, and got him out of his office to take a look at me,” Gehringer later told an interviewer. “I signed a contract with the Tigers, and I can’t remember if I got a bonus. Maybe five hundred dollars. But I would’ve signed for nothing. …When I was a kid, you see, I used to keep a kind of scrapbook. I used to paste newspaper pictures of Cobb and Veach and Harry Heilmann, and here I was going to play with them.”13

The road to the Hall of Fame wasn’t as straight as it looks now.

The American League’s first All-Star second baseman had never played the position before signing with the Tigers. He was a third baseman at Michigan and reported to Detroit as a third baseman, but Cobb, who had Bobby Jones and Fred Haney at third, moved Gehringer to second (behind Del Pratt, Frank O’Rourke, and Bucky Burke) and sent him to the minors.14

He spent 1924 with London of the Class B Michigan-Ontario League, batting .292 in 112 games, and played five games with the Tigers in September. He was promoted to Toronto of the Double-A International League for the 1925 season, batting .325 in 155 games, and played eight games with the Tigers.

Gehringer made the big-league roster in 1926 but started on the bench, which was not where he had figured to be. “I had every assurance that I would start the season at second base, but at the last minute I was benched for O’Rourke. I never got my chance until O’Rourke came down with the measles when the season was about a month old,” he recalled in 1941. “I owe everything to O’Rourke’s measles and to the advice on batting that I got from Cobb.”15

But the relationship with Cobb was bumpy. “Cobb was a hateful guy. Nobody liked him as a manager. He was such a great player himself, he figured that if he told you something, there was no reason why you couldn’t do it as well as he did. But a lot of guys don’t have that ability. He couldn’t understand that. …

“But he was super for the first couple years I was up. Golly, he was like a father to me. … Then all of a sudden he got upset with me about something. To this day I don’t know what it was. He would hardly speak to me. He wouldn’t even tell me what signs I was going to get from the coaches. Weird. But he kept playing me, so it didn’t really matter whether he talked to me or not.”16

Gehringer appeared in 123 games as a rookie and hit .277. The Tigers released Cobb that winter and named George Moriarty manager. Moriarty got Marty McManus from the St. Louis Browns to play second, and Gehringer was moved to third as a backup to light-hitting Jack Warner.17

Again, Gehringer started the season on the bench as the “utility third baseman” while McManus was at second, but again Gehringer got a break. “Marty was taken ill and since I was the only one who could play second base, Moriarty substituted me for McManus. I didn’t miss a game at second until my arm went bad in St. Louis in 1930.”18

In 1927 Gehringer hit .317, beginning a run of 13 .300-plus seasons in 14 years, spoiled only by a .298 in 1932. His breakout season as a hitter was 1929, when he hit .339 and led the league in hits (215), runs (131), doubles (45), triples (19), and stolen bases (27). In 1930, he hit .330 with 201 hits and 47 doubles. He hit .311 in an injury-marred 1931 season; the player who four times led the league in games played appeared in only 101. The following year he played 152 games but hit only .298; he had 44 doubles and 107 RBIs.

The offseason often meant barnstorming, traveling with teams of stars from the major leagues and the Negro leagues, playing in small towns. Gehringer described one such tour: “We went up through the Dakotas and Minnesota and Kansas. Got to bat against Satchel [Paige] every other day, which wasn’t much fun.”19

Paige returned the compliment in his autobiography: “Gehringer was real tough for me, the toughest of all those stickers.”20

The first All-Star Game was held in 1933, and Gehringer was a star among stars. By 1938 he was the only player to have been selected as a starter for every game.21 In the 1934 game, when Carl Hubbell famously ended the first inning by striking out Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx, Gehringer had led off the game with a single. He moved to second on an error before Heinie Manush walked. (Hubbell made it five straight future Hall of Famers by striking out Al Simmons and Joe Cronin to start the second.) Gehringer holds the record (as of 2013) for the highest All-Star batting average, .500 in six games (10-for-20, nine walks, and two stolen bases, including the first in All-Star competition).

In 1934 the Tigers, under new player-manager Mickey Cochrane, bounced back from a fifth-place finish with a 101-53 record and their first World Series appearance since 1909. Gehringer led the AL in runs (134) and hits (214) and was the Tigers’ leader with a .356 average (second to Gehrig by seven points). That was the year the infield combined for 462 RBIs (first baseman Hank Greenberg 139, Gehringer 127, shortstop Billy Rogell 100, and third baseman Marv Owen 96). The Tigers lost the World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games. They made 12 errors in the Series, and Gehringer, who had made only 17 during the season, had three of them. After the season, he was part of the all-star team that toured Japan.

Gehringer led the 1935 Tigers with a .330 average and 123 runs as Detroit returned to the World Series and beat the Chicago Cubs in six games. Gehringer batted .375 in the Series.

The following year, a second-place season for Detroit, Gehringer led the team in batting (.354), runs (144), hits (227), and triples (12), and was the AL leader in doubles (60).

In 1937, at the age of 34, Gehringer became the third Tiger in four years to be selected as the AL’s Most Valuable Player (Cochrane won in 1934 and Greenberg in 1935), finishing four points ahead of 22-year-old Joe DiMaggio of the New York Yankees. Gehringer led the league in batting at .371, 20 points ahead of Gehrig and 25 ahead of DiMaggio. He had 209 hits, 133 runs, and 96 RBIs, the only year from 1932 to 1938 when he failed to reach 100.

The 1938 season was Gehringer’s last as an All-Star; he batted .306 with 107 RBIs and 174 hits. It was also the year he teamed with Ray Forsyth to start a business as manufacturers’ representatives to the auto industry. In previous winters, he had worked in a Detroit department store as a sporting-goods clerk and sold coal wholesale. At one point, he leased two gas stations and hired others to run them.22

Gehringer’s career was winding down; in 1939, he played in only 118 games, hitting .325 on just 132 hits with 86 RBIs. The following year was the last time he hit over .300 (.313); he had 161 hits, walked 101 times (second-most in his career), scored 108 runs and batted in 81 as the Tigers went to the World Series. He played all seven games, batting .214 (6-for-28 with two walks) in the seven-game loss to the Cincinnati Reds.

In 1941 Gehringer played in 127 games, but his average slipped to .220, although he walked 95 times. By 1942, he was a player-coach, posting a .267 average (12-for-45 in 45 games with seven walks) before enlisting in the US Navy in September.23 He served as baseball coach of the St. Mary’s College naval preflight school in California.24 He was discharged in November 1945 with the rank of lieutenant commander.25

“I came out of the service in such good shape that I felt I could’ve played a few years,” Gehringer told an interviewer. “But we had a good business going by that time. Rather than get involved in baseball again and more or less start over with new management, I decided to stick with what I got. So I retired.”26

Gehringer’s bottom line: a .320 average with 2,839 hits, 1,186 walks, 1,774 runs, and just 372 strikeouts in 10,244 at-bats. Seven of his 184 home runs were inside the park. At the end of the 1942 season, he ranked 37th in average and sixth in doubles (574).27 He rated Lefty Grove as the toughest (as well as the fastest) pitcher he faced in his career.28 He hit for the cycle May 27, 1939. He holds the longest consecutive-games-played streak in Tigers history (511 games from September 3, 1927 to May 7, 1931).29 He ranks second in assists by a second baseman and seventh in double plays by a second baseman.

Gehringer was named the second baseman on a fan-selected all-time Tigers team in 1999 when Tiger Stadium closed.30 In 1983 his number 2 and Hank Greenberg’s number 5 were retired by the Tigers.

And he made it look easy.

“I could never figure out when to go for ground balls and when to leave them for Charlie,” recalled Greenberg. “I would dive for one and it would bounce off my glove. Charlie would be standing there, right behind me, and he’d say, ‘I could’ve gotten that one.’ The man was amazing.”31

“He had an uncanny knack for positioning the hitters, and the hands of a magician. No such thing as a bad-hop grounder in the vicinity of Gehringer,” recalled pitcher Elden Auker.32

“Everything he did was so fluid. It looked so easy and yet he covered so much ground. I’d be pitching and a ball might be hit between first and second and I’d say to myself, ‘that’s a base hit into right field.’ Next thing you know it was fielded so easy and the man was thrown out. You wonder how Charlie got there,” Hal Newhouser said.33

As a businessman, Gehringer also had an accomplished career. Forsyth sold him several cars, became a friend and then a business partner. Gehringer and Forsyth sold parts and accessories to the auto industry. Their first success was upholstery buttons, which at the time never held and tore people’s clothing. A woman in New York, Ann Friedolph, had patented one that held, and her patent attorney was a friend of Gehringer’s and Forsyth’s. Ford and Chrysler signed up, and General Motors followed. “We sold a jillion,” Gehringer said. They added other products, including upholstery material, carpeting and other interior materials.34 He retired in 1974.35

“The name would get you in, but it wouldn’t get the job done. I put in an eight-hour day and worked hard,” Gehringer said. “Some of those prospective customers in the automobile industry were really tough. They’d say to me, ‘What do you know about this business?’ I’d say, ‘Maybe not much, but I didn’t know much about baseball either when I started.’ ”36

Although he was retired, Gehringer wasn’t finished with baseball. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1949 but did not attend the induction ceremony on June 13 because he was preparing for his wedding. The voting had taken place in January with no one elected; Gehringer was elected in a runoff, but his wedding plans had been made well in advance and he told Cooperstown he had “pressing business.”

Despite being one of Detroit’s most eligible bachelors, Gehringer had not married. He had moved his diabetic mother into the first house he bought, in 1934; because she needed some care, Gehringer did not want to bring a wife into the mix.37 He met Josephine Stillen when he made sales calls to Nash-Kelvinator, where she worked in the purchasing department. She knew he had been a ballplayer, and especially remembered him from the 1934 and 1935 World Series. He gave her tickets to a game, and she went with a friend, but the game was rained out. Then she went to a game with him. “I never dreamed we’d be a twosome,” she recalled. “I’m glad that we met. … I knew he liked his privacy and could protect him over the years.”38

That started with the wedding. The plan was for a small one in Santa Clara, California, where Marv and Violet Owen lived and no one knew the Detroiters. Gehringer had been the best man at their wedding. However, word got out and people started camping out at the church. Owen contacted the priest, who suggested a church in San Jose, six miles away, and they sneaked in the back door.39

Gehringer was in Cooperstown the next year, and almost every year thereafter. He missed only ten ceremonies in the ensuing 42 years, nine of them while he was still working full-time.40 He served on the Hall of Fame’s veterans committee from its creation in 1953 until 1990 and was a member of the Hall’s board of directors until 1991.41

Gehringer returned to the Tigers as general manager from August 1951 until the end of the 1953 season and was a vice president until 1960. His baseball encore was not pleasant.

“I did not enjoy it. I had been away for nearly ten years and I didn’t know the leagues. I was more or less forced into it,” he recalled. “W.O. (Briggs) told me he needed me and then he stuck his hand out. I couldn’t turn him down.”42 He inherited a team that had been rewarded with high salaries after just missing the pennant in 1950, and he was forced to make trades to pare the payroll. Those 1952-53 Tigers finished a combined 110-198-6. However, Gehringer did sign future Hall of Famer Al Kaline in 1953.

Gehringer was a regular at the Yankees’ Old Timer’s Days, and it was the 1965 game, at the age of 62, that truly finished him as a player: “I hit a ball between the center fielder and right fielder, and was going to stretch a triple into a double, but I fell right across first base.”43 It was his first at-bat, against Jim Konstanty. He had surgery for a ruptured Achilles tendon the following week.44

Golf was his game by then, anyway. In 1929, the people of Fowlerville held a day for Gehringer at Navin Field and presented him with a set of matched Spalding woods and irons in a leather bag. “They were also right-handed, and of course I’m left-handed,” Gehringer recalled. “But I learned how to play the game right-handed.”45

Gehringer was visibly active in the March of Dimes, serving 20 years as Wayne County chairman,46 the Big Brothers, the Boys and Girls Clubs, and Oakland University.47 He held many autograph sessions for the March of Dimes in what his wife recalled as “dives,” and was a popular speaker for years, telling one interviewer, “I think I’ve been in every church basement in the city of Detroit.”48

Despite having been out of the game for decades and being an intensely private person, Gehringer was not forgotten by fans and autograph hounds. The Gehringers’ home was on a large, secluded lot in a Detroit suburb, but many meals were interrupted by people ringing their doorbell, demanding time and/or an autograph, simply because they had “driven all the way from Chicago.”49 “I don’t know how they found out where we lived,” Josephine said, adding that he was often accosted at restaurants and asked if he were the former ballplayer. His reply? “My name is Schultz.”50

Then there was the mail, which increased as Gehringer became one of the oldest living Hall of Famers. Former baseball writer Jim Hawkins met him at a baseball card show in the 1980s and worked with him when Gehringer decided that the requests were overwhelming. Hawkins called it a “feeding frenzy.”

“Ninety-five percent of the requests were from people planning to resell Charlie’s autograph,” said Hawkins. Just getting the hundreds of items home from the post office each week was a challenge, as was keeping the requests straight, many of which came without return postage. Hawkins took over after the Gehringers returned from a two-week vacation in 1990 to find more than 500 pieces of mail at the post office – balls, bats, baseball cards, photos.51

“That was when and why Charlie began charging for autographs and requesting that all such mail be sent to me,” said Hawkins. “We did so until the end of his life. But believe me, he didn’t do it for the money. He did it for his quality of life and peace of mind.”52

Gehringer died on January 21, 1993, of complications from a stroke he had suffered a month earlier. He was 89. He had no children.

This biography is included in the book “Detroit the Unconquerable: The 1935 World Champion Tigers” (SABR, 2014), edited by Scott Ferkovich.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Josephine Gehringer, Mike Grimm, and Jim Hawkins for their time and help, and Bob Byrnes for his encouragement.

Sources

Auker, Elden, with Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001), 113.

Bak, Richard, Cobb Would Have Caught It (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 190-207.

Hawkins, Jim, and Dan Ewald, The Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003), 58, 283-284.

Paige, Leroy (Satchel), as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 1993), 103.

Winegar, C. Henry, and George O. Winegar, Descendents of Adam and Maria Gehringer (Saline, Michigan: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc., 1993).

Michael Grimm, “Charlie Gehringer,” Fowlerville History fowlervillehistory.org/baseball/charliegehringer/

Baseball-reference.com

“Roll call of past induction ceremonies,” Baseball Hall of Fame baseballhall.org/sites/default/files/all/Documents/roll_call_of_past_induction_ceremonies.pdf

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Charlie Gehringer.

Notes

1 Jim Hawkins and Dan Ewald. The Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003), 58. (one variation; also attributed to Doc Cramer, Mickey Cochrane, and possibly others).

2 C. Henry Winegar and George O. Winegar. Descendants of Adam and Maria Gehringer (Saline, Michigan: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc., 1993).

3 Michael Grimm, “Charlie Gehringer,” Fowlerville History. fowlervillehistory.org/baseball/charliegehringer/.

4 Sheldon A. Mix, “A Visit With the Second Baseman,” Gehringer-Kaline Meadow Brook Golf Classic 1988.

5 Richard Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 191.

6 Mix, “A Visit with the Second Baseman.”

7 Grimm, “Charlie Gehringer,” Fowlerville History; Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 191.

8 Michael Grimm, interview with author, August10, 2013.

9 Mix, “A Visit With the Second Baseman.”

10 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 191.

11 Kent Reichert, University of Michigan Athletic Department, email correspondence with author, July 22, 2013. Gehringer told Bak in Cobb Would Have Caught It, “Funny thing is, I won a letter in basketball but I didn’t get one in baseball,” 191. The University of Michigan has only a record of his winning a freshman letter in baseball.

12 Kay Lash, Local History and Genealogy Dept., Carnegie Public Library of Steuben County, Indiana, email correspondence with Michael Grimm, March 4, 2011.

13 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 191-192.

14 J.G. Taylor Spink, “The Mechanical Man and Tennyson’s Brook,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1941.

15 Spink, “The Mechanical Man and Tennyson’s Brook.”

16 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 192.

17 Spink, “The Mechanical Man and Tennyson’s Brook.”

18 Ibid.

19 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 194.

20 Leroy (Satchel) Paige as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 1993), 103.

21 Tom Meany, “High Tribute to Gehringer,” New York World-Telegram, July 6, 1938.

22 Watson Spoelstra, “Gehringer a Blue-Chip Businessman,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1966.

23 “Gehringer Back On Active List,” United Press, May 22, 1942.

24 “Spike Nelson Gets Navy Grid Post,” United Press, February 27, 1943.

25 navymemorial.org/navy-log.

26 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 206.

27 baseball-reference.com (extrapolated).

28 “Gehringer Calls Grove Fastest of All,” Associated Press, 1943 (Cooperstown file, no month or day).

29 Hawkins and Ewald, The Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia, 283.

30 “Tiger fans pick all-time team,” Associated Press, September 26, 1999.

31 Hawkins and Ewald, The Detroit Tigers Encyclopedia, 58.

32 Elden Auker with Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001), 113.

33 George Puscas, “Charlie Gehringer 1903-1993/Incomparable 2nd Baseman in Glory Years,” Detroit News and Free Press, January 23, 1993, 1A.

34 Spoelstra, “Gehringer a Blue-Chip Businessman.”

35 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 207.

36 Mix, “A Visit With the Second Baseman.”

37 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 207.

38 Josephine Gehringer, interview with author, August 9, 2013.

39 Josephine Gehringer, interview with author, August 9, 2013.

40 Baseball Hall of Fame. baseballhall.org/sites/default/files/all/Documents/roll_call_of_past_induction_ceremonies.pdf

41 Bill Deane, email correspondence with author, Oct. 1, 2013.

42 Spoelstra, “Gehringer a Blue-Chip Businessman.”

43 Mix, “A Visit With the Second Baseman.”

44 “Gehringer Fine After Operation,” United Press International, August 7, 1965.

45 Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, 207.

46 (no headline; notes at end of an article) Unknown Detroit paper (from Cooperstown file), January 9, 1971.

47 Josephine Gehringer, interview with author, August 9, 2013.

48 Mix, “A Visit With the Second Baseman.”

49 Josephine Gehringer, interview with author, August 9, 2013.

50 Josephine Gehringer, interview with author, August 9, 2013.

51 Jim Hawkins, email correspondence with author, August 28-29, 2013.

52 Jim Hawkins, email correspondence with author, August 28-29, 2013.

Full Name

Charles Leonard Gehringer

Born

May 11, 1903 at Fowlerville, MI (USA)

Died

January 21, 1993 at Bloomfield Hills, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.