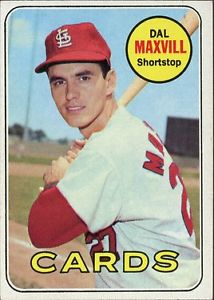

Dal Maxvill

In the history of the St. Louis Cardinals, there have been many wonderful shortstops. Think of the flamboyant Leo Durocher, the slick-fielding MVP Marty Marion, and the Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith. To their number add Charles Dallan Maxvill, who went from barely making the team to building a major-league career that lasted 14 years, most of them with the Cardinals. He earned four world championship rings and became a trusted major-league coach and finally the general manager of the Cardinals. Dal Maxvill lived a young boy’s baseball dream.

The Cardinals had been Dal’s favorite team since he was a youngster growing up in a St. Louis suburb, Granite City, Illinois, where he was born on February 18, 1939, to Harold and Eileen Maxvill. Harold was a steelworker. His parents took him to Sportsman’s Park, where he saw the Cardinals legends of the 1940s and early ’50s, including seven-time All-Star shortstop Marty Marion. When he was 11 years old, Dal wanted to play in the Khoury League, a youth baseball organization centered in the St. Louis area. Most of his friends’ fathers were too busy working in the steel mills to coach his team, so Eileen volunteered to be the manager. Dal rode the handlebars of her bicycle taking the team’s gear to the practices and games. Dal was always underweight, so his family tried to help him gain a few pounds. His grandmother financed a series of shots intended to improve his appetite. “But all I got out of the shots was a sore arm,” he said.1

Dal played baseball at Granite City High School. A 5-foot-11, 135-pound infielder when he got out of school, he received baseball scholarship offers from the University of Missouri and Northwestern University.2 He turned them down to attend Washington University in St. Louis, which had a good engineering school. The fact that his girlfriend, Diana Sinclair, was in St. Louis helped him make his college choice. Maxvill financed part of his college education by working at Granite City Steel as a laborer for several summers. He eventually received an academic half-scholarship, and graduated in 1960, after 3½ years, with a degree in electrical engineering and a senior-year .350 batting average on the Bears’ university baseball team.

The major-league scouts considered Maxvill too small, but Irv Utz, his college coach, arranged a tryout with the Cardinals. By chance, one of the St. Louis affiliates needed a defensive infielder, so scout Joe Monahan signed him. Bing Devine, the Cardinals’ general manager (also a Washington University graduate), assigned Maxvill to Winnipeg, a Cardinals affiliate in the Class C Northern League. He received a $1,000 bonus and a promise of $1,000 more if he lasted the full season. He did last the season, playing in 74 games and batting .257 as the Goldeyes won the Northern League pennant. Maxvill began the 1961 season in Winnipeg, but was moved up to the Cardinals’ Triple-A team in Charleston, West Virginia (International League), in time to play 88 games there.

The Cardinals moved Maxvill to Double-A Tulsa (Texas League) to start the 1962 season, but brought him up after he batted .348 and fielded well in 47 games. He played in 79 games for the Cardinals and batted .222. In 1963 he started only five games at shortstop because Dick Groat, acquired from Pittsburgh and the regular shortstop, was having another All-Star year. At the beginning of 1964 the Cardinals sent Maxvill to Triple-A Jacksonville, where he fielded well but hit an anemic .140 in 38 games. The Cardinals sent him on loan to Indianapolis, a White Sox farm team, in June. While traveling to report to Indianapolis, Maxvill thought about quitting baseball and going home to work at Bussmann Fuse Company, his offseason employer. At the airport in Chicago he spoke by phone to his wife, Diana, who encouraged him to continue in baseball, and Maxvill decided to report to Indianapolis.

He made the right decision, because after playing in 45 games for Indianapolis, batting .285, and continuing to field well, he was called up by the Cardinals. After playing in only a half-dozen games as a backup to Groat, and getting only six hits in 26 at-bats, Maxvill started at second base in the all-important last game of the season against the New York Mets. Julián Javier, the regular second baseman, was out with a bruised hip. The Cardinals had lost the first two games of the three-game series in St. Louis. If they lost this game, there could be a three-way tie for the lead in the National League, or they could lose the pennant if the Reds won their game. A Cardinals win would give them the pennant, if the Reds lost to the Phillies.

Manager Johnny Keane told Maxvill the night before the big game that he would be the second baseman for the pivotal game. “All I could think was if somebody hit the ball to me, I wanted to get them out,” Maxvill said after the game.3 He got the hitters out, but also got two big hits in the game. He came up in the fourth with the score tied, 1-1, two out and Groat on second. Maxvill singled to center off Galen Cisco, the Mets hurler, to give the Cardinals the lead. The Mets went ahead, 3-2, in the top of the fifth. In the bottom of the inning the Cardinals went ahead, 4-3, and Maxvill came to bat again. He got another run-scoring single to make it 5-3. The Cardinals eventually won, 11-5, to clinch their first National League pennant since 1946. (Philadelphia had already defeated Cincinnati.)

Next came the World Series and the New York Yankees with Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. Maxvill started every game at second base. (He was pinch-hit for in the late innings of three games.) Maxvill batted only .200 (4-for-20) but Keane was pleased with his play and the way the youngster handled the pressure. In Game Seven Maxvill singled home Mike Shannon in the fourth inning to make the score, 3-0, and he caught the ninth-inning popup by Yankee Bobby Richardson that ended the game and gave the world championship to the Cardinals.

But 1965 was a different season. Javier had healed and Groat was still the Cardinals’ regular shortstop. As a result, Maxvill had only 89 at-bats in 68 games. No matter that in spring training general manager Stan Musial had called him the “take-charge leader of the Cardinals’ infield.”4

Maxvill continued to use his engineering degree by working in the offseason for Bussman Fuse Company. He usually traveled around the country demonstrating and selling fuse systems.

Groat was traded after the 1965 season but Maxvill did not automatically inherit the shortstop position in 1966. In spring training Jerry Buchek, Jimy Williams, and Phil Gagliano were the biggest competition to him. Coach Dick Sisler worked with Maxvill to improve his hitting, spending extra time in the batting cage with him. “Dick got me to wait on the ball better and hit to right field more consistently,” Maxvill said. “He had me moving around better at the plate so I could handle certain pitches better.”5

Finally, in early June, Maxvill became the regular shortstop. Red Schoendienst, his manager, felt that his defensive abilities made the infield stronger. Pitchers, especially Bob Gibson, wanted Maxie — as he became known — fielding behind them in every game. Although he batted only .244 for the season, Maxvill delivered numerous key hits and drew 37 walks to tie Shannon for the most on the team. After the season, Maxvill was selected Khoury Major Leaguer of the Year, beating out ten other major leaguers who started their baseball careers in the Khoury League organization.

Maxvill began spring training of 1967 knowing he was the starting shortstop. He was pleased, telling a sportswriter, “Not many players like to be picked up, or substituted for. I don’t. I want to play every day, all the time. It’s an old story in baseball — rest two days and maybe you rest five years.”6

Things went well for regular shortstop Maxvill and the 1967 Cardinals. He played in 152 games and had 14 runs batted in during September. His fielding percentage at shortstop, .974, was tied for second-best in the league. He also appeared in seven games at second base, where he did not make an error.

The Cardinals again went to the World Series, this time against the Boston Red Sox. The Series went down to the seventh game at Fenway Park. Jim Lonborg, the Red Sox starter, had won 22 games in the regular season, and was the Cy Young Award winner in the American League. Lonborg had won Games Two and Five with commanding complete-game efforts. Maxvill led off the third inning with a triple off the center-field wall and scored the Cardinals’ first run when Curt Flood drove him in with a single. With nobody out in the ninth inning, Maxvill grabbed a hard groundball in the hole and teamed with Javier for a rally-killing double play. The Cardinals went on to win, 7-2, to claim their eighth world championship.

The 1968 season was another good one for Maxvill and the Cardinals. He was the National League Gold Glove winner at shortstop, and his .253 batting average was the highest of his major-league career. Maxvill was the only Cardinal who started every game in the club’s stretch of 59 games in 56 days after the All-Star break.7 The Cardinals went to the World Series again, this time losing to the Detroit Tigers in seven games. Maxvill was 0-for-22 at the plate, a World Series record for futility.

The Cardinals had the highest payroll in baseball. In those pre-free-agency days, that brought criticism of the organization from elsewhere in baseball. But manager Schoendienst and general manager Devine defended the players. “Some highly placed baseball people believe that by paying so well the Cardinals are undermining the very structure of baseball,” a Sports Illustrated writer said just before the World Series, adding a comment from Devine: “Almost every place I go … someone will ask me how Dal Maxvill can be making $37,500. It really seems to bother people, but if you have seen the way he has played shortstop this year and how he gets himself involved in the good things we do, his salary won’t surprise you.”8 Indeed, Maxvill’s salary went up to $45,000 in 1969.

High salaries and all, the 1969 and 1970 seasons were forgettable for Maxvill and the Cardinals. The team finished in fourth place both years, 13 games behind the division winners in the NL East. One bright spot for Maxvill came on April 14, 1969, when he hit the first major-league grand slam in Canada during a Cardinals-Montreal Expos game at Parc Jarry. But in the 1970 season he failed to hit a homer in 152 games and 399 at-bats. The Cardinals did better in 1971, winning 90 games but finishing in second place, seven games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Maxvill was respected and popular among his teammates, who named him their union representative. The responsibility put Maxvill in a tough spot during the players’ strike in the spring of 1972. He thought the fans did not understand the players’ side of the squabble, which erased the first week of the season. On August 28 he was named Sportsman of the Year by the Southside Kiwanis Club in St. Louis. Two days later he was traded to the Oakland Athletics for two minor leaguers.

Maxvill played in most of the remaining games for his new club, usually at second base. He wanted to play every inning of every game, but the Oakland manager, Dick Williams, used a rotating second baseman system. Williams used 11 shortstops/second basemen that season. Most of the time, the second baseman who started the game would not be around to finish it. He would usually be taken out for a pinch-hitter early in the game. On September 28 Maxvill was the fourth second baseman the A’s used against Minnesota. He batted in the bottom of the ninth with the game tied and a runner on first. His double to left field won the game, 8-7, and gave Oakland a six-game lead in the American League West, with five games to play Oakland had won its second successive American League West title. The A’s finished 5½ games ahead of the Chicago White Sox for the West Division title, and went on to beat the Detroit Tigers in the American League Championship Series. Maxvill played in every game of that ALCS, starting three of them at shortstop. He was ineligible for the World Series, in which the A’s beat the Cincinnati Reds, but was awarded a World Series ring and was voted a half-share of the World Series money.

Maxvill played only sporadically for the A’s in 1973, and on July 7 he was sold to the Pirates, who ended up in third place, 2½ games behind the Mets. He started the 1974 season with the Pirates but was released on April 20 and went home to St. Louis to help operate Cardinal Travel, an agency he and former Cardinals teammate Joe Hoerner, along with other investors, had started in 1969. He did not stay there long, as the Athletics came calling on May 10, and he signed with them. He played in 60 games and had 52 at-bats and ten hits for the A’s. The A’s again won the AL West, and played Baltimore in the league championship series. Maxvill appeared in one game in the ALCS, with only one at-bat, in which he struck out. The A’s went to the 1974 World Series and won over the Los Angeles Dodgers in five games. Maxvill played in two games, with no at-bats, and received his fourth World Series ring and a full World Series share. He was released after the season but re-signed as a coach and utility infielder, at a salary of $40,000. He played in 20 games in 1975 and had two hits in ten at-bats. He was released by the A’s on October 10, 1975. In November Maxvill officially retired from baseball. By this time he was 36 and ready to settle down in St. Louis and put his talents to work at the travel agency. In a few years, however, he was back in baseball as Joe Torre, now the manager of the Mets, signed him to coach third base for the 1978 season. Torre respected Maxvill’s knowledge of the fundamentals of baseball, and thought that his former Cardinal roommate could help improve the play of his infielders. Maxvill resigned after the season, again to be closer to home and his travel business. But baseball called again, and quickly. In October, he and Red Schoendienst were hired as coaches for the Cardinals under manager Ken Boyer. Fans reacted favorably because both lived in St. Louis, and were well liked in the baseball community. By that time Maxvill had four children and appreciated the opportunity to have a baseball job close to home. He coached for the Cardinals in 1979 and 1980. Whitey Herzog became the Cardinals’ manager in June 1980, hired his own coaches, and in 1981 Maxvill became a minor-league instructor.

When Torre became manager of the Atlanta Braves in 1982, Maxvill again became a coach for his good friend. After the 1984 season, Torre was fired and Maxvill was the only coach retained by the Braves.

The Cardinals fired their general manager, Joe McDonald, in January 1985. In February, during the Braves’ spring training, the Cardinals came calling again, asking Maxvill, now 46, to interview for the position of general manager. The team was looking for someone with a good head for business and a working knowledge of baseball and of the Cardinals organization. Maxvill and team owner August Busch Jr. talked on Busch’s yacht off St. Petersburg. After the meeting, Busch asked Maxvill to leave for a while, so he could have a discussion with other team officials. Dal walked along the beach for a half-hour. When he returned, he was offered the position. He was officially named general manager on February 25, 1985. Maxvill was now the GM for Herzog, the man who had sent him down to coach in the minors.

Maxvill was enthusiastic about the opportunity to help shape the team he had followed since he was a boy. “It would be awfully nice to be humble,” he said, “but I can handle the job. It will be fun, a challenge. If I thought I couldn’t do the job, I wouldn’t have talked to them when they approached me.”9 His contract would be for one year at a time. The team’s chief operating officer, Fred Kuhlmann, would be in charge of business matters. Everything would have to be approved by the executive committee and then by Busch.

Maxvill’s rookie season as general manager was a good one. In his first trade he acquired José Oquendo from the Mets for Ángel Salazar, on April 2, 1985. For ten years Oquendo proved to be a valuable utility player for the Cardinals, and became a popular coach in 1999. In a surprising turn of events, the 1985 Cardinals, whom many picked to finish last in the NL East before the season started, won 101 games and defeated the Dodgers in the NLCS. They battled Kansas City in what became known as the I-70 World Series, for the interstate highway that connected the two cities. The Cardinals were two outs away from winning the Series in Game Six before the Royals rallied to win that game and then Game Seven. The next season, 1986, the Cardinals finished three games under .500 and ended the season 28½ games behind the Mets, but in 1987 they again won the NLCS, this time over the Giants, before losing the World Series to the Minnesota Twins in seven games. In 1988 St. Louis ended in fifth place, ten games under .500, in the NL East.

As general manager, Maxvill often voiced his concern about escalating salaries in baseball. He had to contend with a manager, Herzog, who freely offered his ideas on ways to improve the team. Before the 1989 season, pitchers Danny Cox and Greg Matthews were injured. Herzog wanted Mark Langston, a left-handed starting pitcher for Seattle. Even though Maxvill and Herzog agreed that the price for Langston was too high, the manager kept insisting on acquiring Langston. “When you’re a manager, you want to have a club that can compete, that has a fair shake when you go out there. Last year we didn’t have that from day one,” Herzog said.10 Langston went to the Expos in a July trade and Herzog continued to have issues with the pitching.

The Cardinals finished the 1989 season in third place, seven games behind the division-winning Chicago Cubs. In late September the Cardinals also lost their primary backer at the brewery when August Busch, Jr. died at the age of 90. There was a restructuring of the team’s top brass. Kuhlmann became the president and CEO, and August Busch, III, who had no interest in baseball, was the chairman of the board.

Another example of the difficulties escalating salaries posed Maxvill was his contract negotiations with Cardinals third baseman Terry Pendleton, who had been awarded a Gold Glove in 1989 and batted .264. The issue went to arbitration, and Pendleton was awarded $1.85 million, the second highest amount given to a player in arbitration to that point. As much as he would have liked to keep Pendleton a Cardinal, Maxvill could not afford to sign him to a long-term deal at that price, and Pendleton went to the Braves as a free agent after the 1990 season.

By June 1990 the Cardinals were last in the National League in batting with a .235 average. Maxvill insisted that he would not make changes just to “shake things up.” He was in a bind because 11 of the players were going to be free agents at the end of the season. The management did give Maxvill an endorsement by extending his contract another year, even though the team lost 39 of its first 66 games.

On July 6, 1990, Herzog resigned as manager. The team was in last place and playing poorly. Herzog could not motivate them and no trade was imminent. The number of free agents also bothered Herzog. Joe Torre eventually became the new manager, but the Cardinals finished in last place in the NL East, 25 games out. During the winter they lost several players to free agency. Maxvill had to work within the conservative budget of the brewery to try to put a winning team on the field. He had to find inexpensive young talent to replace the expensive free agents they had to let go.

For the next two seasons, the Cardinals sang the familiar refrain. They would not go after free agents. After the 1992 season, they had ten players who could apply for free agency. They re-signed Ozzie Smith but let the others leave. The Cardinals finished in third place in 1993, ten games behind the Phillies. After the season, Maxvill admitted that the team needing pitching help but added, “Unfortunately, we are looking for a pitcher who doesn’t make a lot of money.”11

The 1994 season quickly disintegrated. The team was having trouble winning games, and then the players union went on strike on August 11, wiping out the remainder of the season. In August Mark Lamping, a former Anheuser-Busch executive, was hired as president of the Cardinals. In September he fired Maxvill. Dal continued to draw his salary through 1995, doing some specialized scouting. He was 55 years old. He did some scouting for the Yankees for a while. Otherwise, he stayed away from baseball.

Sources

Feldmann, Doug, St. Louis Cardinals Past & Present (Minneapolis: MVP Books, 2009)

Goold, Derrick, 100 Things Cardinals Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010).

Allen, Maury, “Cards’ New GM Rarin’ to Rebuild.” New York Post, April 11, 1985

Daley, Arthur, “Sports of the Times.” New York Times, March 28, 1969

Herman, Jack, “Rookie Executive,” St. Louis Weekly, July 19, 1985 (article from Maxvill player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Chicago Daily News

St. Louis Globe Democrat

St. Louis Post Dispatch

St. Petersburg Times

Sports Illustrated

The Sporting News

National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

New York Mets Scorebook, 1978

St. Louis National Baseball Club, Inc.

St. Louis Mercantile Library at University of Missouri-St. Louis

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Neal Russo, “Dal Maxvill: Classy Card Minute-Man,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1965.

2 Neal Russo, “Little Maxie Getting Big Cardinal Hits,,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1968.

3 Milton Gross, “Dal Maxvill No Bat Boy,” Chicago Daily News, October 5, 1964.

4 Jack Herman, “Musial High on Maxvill,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, March 11, 1965.

5 Neal Russo, “Alley Route Best for Me, Says Maxvill,” The Sporting News, January 7, 1967.

6 Jimmy Mann, “Pickup Man Who Made Good,” St. Petersburg Times, 1967.

7 Bob Harlan, St. Louis National Baseball Club, Inc. press release, February 18, 1970.

8 William Leggett, “Manager of the Money Men,” Sports Illustrated, October 7, 1968.

9 Jack Herman, “Rookie Executive,” St. Louis Weekly, July 19, 1985.

10 The Sporting News, March 27, 1989.

11 Rick Hummel, The Sporting News, November 8, 1993.

Full Name

Charles Dallan Maxvill

Born

February 18, 1939 at Granite City, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.