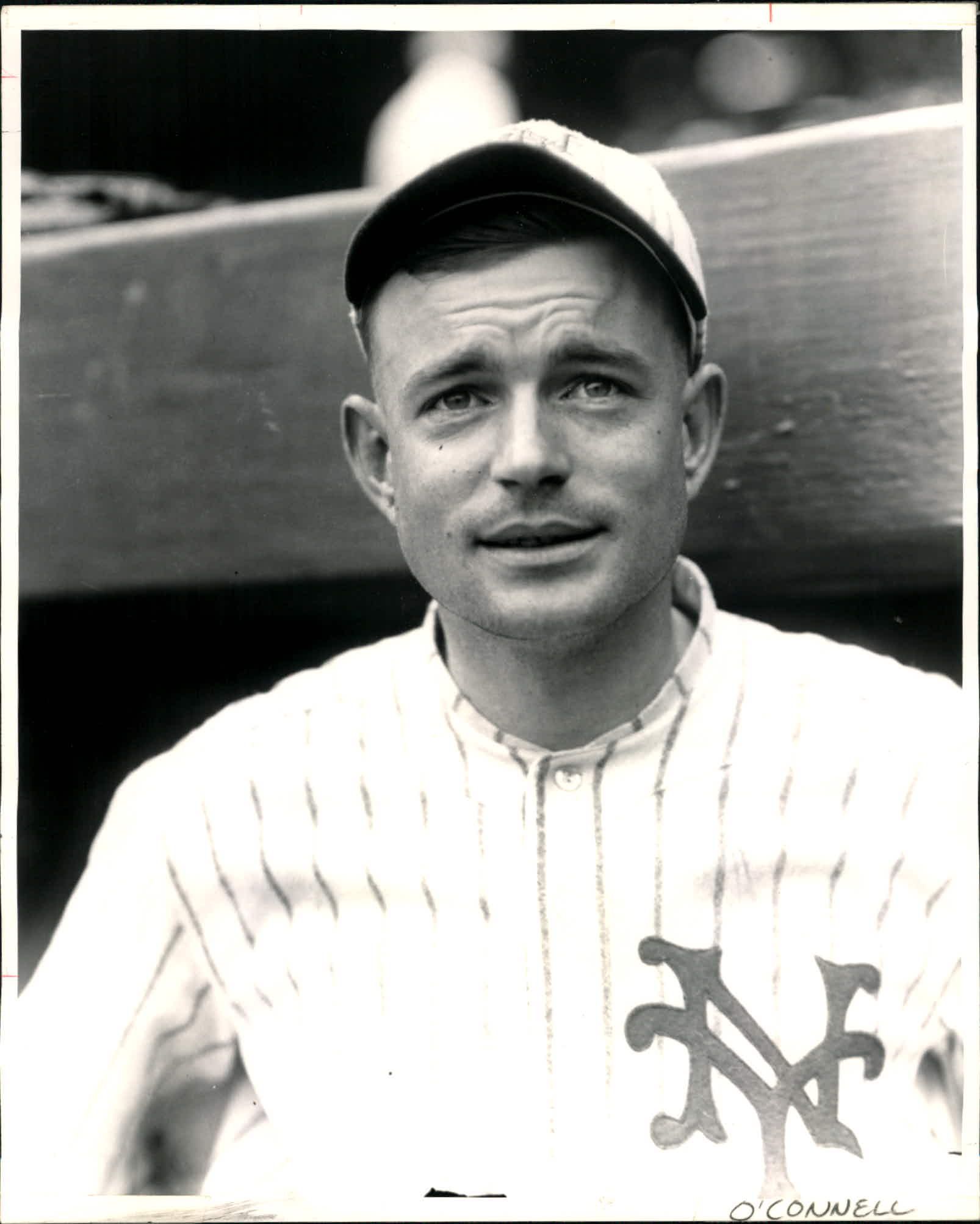

Jimmy O’Connell

Twenty-three-year-old Jimmy O’Connell was a happy young man who had a lot to look forward to. The outfielder had just finished his second season with the National League pennant winners, the New York Giants, posting a .317 batting average. He was about to play in the World Series for the second straight year. His second wedding anniversary was a few days away, and he was going to take his wife to a show on the evening of Tuesday, September 30, 1924.

Twenty-three-year-old Jimmy O’Connell was a happy young man who had a lot to look forward to. The outfielder had just finished his second season with the National League pennant winners, the New York Giants, posting a .317 batting average. He was about to play in the World Series for the second straight year. His second wedding anniversary was a few days away, and he was going to take his wife to a show on the evening of Tuesday, September 30, 1924.

That afternoon, the phone rang in O’Connell’s rented room at New York’s Embassy Hotel. O’Connell answered. The person on the other end of the line told him that Kenesaw Mountain Landis was in town, staying at the Waldorf Astoria, and wanted O’Connell to come to his hotel suite for a 4:00 PM meeting. O’Connell was baffled. Why would baseball’s commissioner want to see him? He walked down to the lobby with his wife. Before catching a cab and riding to the Commissioner’s hotel, he told her he would be back in about 15 minutes. Little did he know that the forthcoming meeting would result in his expulsion from affiliated ball.

James Joseph O’Connell was born on February 11, 1901, in Sacramento, California. He was the youngest of three children born to James (a firefighter) and Bertha O’Connell. His older brother was Edgar; his older sister was Margaret.

Early in life, young Jimmy learned that honesty was the best policy. According to his father, the boy told fibs during childhood, and for each untruth, his father severely punished him. To help correct the problem, the father purchased a portrait of George Washington and placed it on the wall above the family’s dining room buffet. “There’s the first president of the United States, who never told a lie in his life,” Mr. O’Connell told his son. “Whenever you’re tempted to fib, remember George Washington.”1

Jimmy learned, matured, and became a star sandlot baseball player. After childhood, he attended the University of Santa Clara (now Santa Clara University), starred on the school’s baseball team, and played semipro baseball in Santa Clara during the summers. That’s where Alfie Putnam, co-owner of the San Francisco Seals, found him during the fall of 1919. The Seals signed the “lanky kid,” and O’Connell joined his new team during the final few weeks of the season. He made an immediate impression by going 10-for-32 in eight games. “If he isn’t a ballplayer then I am a Swiss watchmaker, and there are times when I can’t even tell the time,” quipped San Francisco sportswriter Ed R. Hughes.2

When O’Connell reported to the Seals for spring training in 1920, he continued to impress. “That boy will be as great a sensation as Bob Meusel was last year,” predicted Seals team president Doc Strub. “He looks like Harry Heilmann did when he was a kid,” said a baseball scout. “Why, he looks a thousand per cent better than Heilmann did when breaking in,” said Putnam.3

The young sensation, who had just turned 19, also caught the attention of a major-league team. “I don’t know whether Jim O’Connell could catch a fly ball or not. But I do know he can hit that baseball, and I will give you a certified check for $10,000 for him right now,” Cubs manager Fred Mitchell told Seals manager and part owner Charlie Graham while observing O’Connell taking batting practice prior to a Cubs-Seals exhibition in San Francisco.4 Because the Seals needed hitters and wanted O’Connell for themselves, they declined the offer.

In 1920, O’Connell’s first full season in the Pacific Coast League, he hit only .262 and made just 12 extra base hits while batting primarily against right-handed pitching. “This young man looks like a hitter and he acts like a hitter, but he has not been crashing the ball like he should,” wrote Ed R. Hughes. “If the kid would only take his natural cut at every good ball offered to him, he would get himself talked about quite a lot, for when he does take a healthy swing and meets the ball, he drives it like a shot.”5

It was reported before the 1921 season that O’Connell lacked confidence and was unsure of himself. However, when the season began, O’Connell – placed in the starting lineup against right handers and left-handers – got off to a good start and was said to be getting better every game. As he maintained good batting numbers into the summer, major-league teams took notice. “He hits low balls and he hits high ones; he hits them on the inside and on the outside; he hits fast balls, curves, and slow ones; he hits right-handers and left-handers – what more could you ask in a man?” said Yankees scout Bob Connery.6

“He’ll be one of baseball’s brightest stars,” said Cubs scout Jack Doyle.7

“Great young prospect; no telling what heights he will climb,” said White Sox scout Danny Long.8

It was reported that Reds scout Russ Hall begged Charlie Graham for one favor: a chance to bid on O’Connell when the time came. When O’Connell finished the 1921 season with a .337 batting average, 17 homers, and a .505 slugging percentage, the time was right. Major-league teams began negotiating a purchase price for the highly rated first baseman-outfielder. When the Seals placed a $75,000 price tag on the touted 20-year-old, most teams backed off. But someone who was unfazed was Giants manager John McGraw. The Yankees were also interested and made a counteroffer, but the Giants won the prize.

On December 8, 1921, it became official. The Giants purchased O’Connell with an agreement that the youngster wouldn’t report to them until 1923. The amount was the highest ever paid for a minor-leaguer at the time. When McGraw returned to New York City following the baseball winter meetings, he was reportedly elated. “O’Connell played a wonderful game on the coast last season, and although he is only twenty years of age, he gives promise of developing into an exceptional player,” said McGraw. “He has shown great form as a first baseman, but he has also had considerable experience as an outfielder, and at the present I intend to use him in the outfield.”9

In 1922, O’Connell’s first order of business upon reporting to the Seals for spring training was to demand $7,000 for his share of the purchase price. “It is reported unofficially that the demand was met through a presentation of cash,” reported the New York Times. Then O’Connell and the Seals talked contract, and the parties agreed at around $10,000. “O’Connell, under the contract signed today, will receive the largest salary ever given to a minor-league baseball player,” Putnam said.10

When the season began, O’Connell got off to a great start: he was hitting .450 in mid-May. One month later, he was still hitting over .400 and leading the league in hits and runs. In a game in late September, O’Connell went 6-for-6 with two home runs, a triple, a double, two singles, and four runs scored. Before another game in late August, San Francisco honored the youngster with a “Jimmy O’Connell Day.” Before a packed park, O’Connell was showered with gifts, including a handsome gold watch. When the home crowd yelled for speech, O’Connell smiled, blushed, and headed to the clubhouse with his gifts.

On October 2, sportswriters learned that O’Connell was having stomach problems, would miss the game that day, and would head home from Sacramento to recover.11 The next day, however, the press learned that O’Connell wasn’t ill; rather, he had secretly married a girl from Casper, Wyoming, named Esther Margaret Doran. With only family members present, Jimmy and Esther were married at the St. Thomas church in Los Angeles.

When O’Connell arrived for 1923 spring training with the Giants, “he was interviewed and photographed to death.”12 “When not in uniform, he looks extremely young and immature, quiet spoken, modest, and smaller in size than one would think,” a writer described. “But in uniform he is a 200-pound youngster with broad shoulders and sturdy legs, and an impressive looking specimen of humanity.”13 During an early spring batting practice, he was the first Giant to clear the right-field wall.

During one of the first team workouts, O’Connell also impressed his new manager. “As good a fadeaway [slide] I ever saw,” McGraw said after a morning team practice at the sliding pit.14 But while his base running and hitting were impressive, it was reported that he lacked grace in the outfield and had a peculiar throwing motion. It was also reported that O’Connell was not at full strength. He was coming off a bout with scarlet fever and was said to be suffering from homesickness. McGraw was planning to play O’Connell in the everyday lineup, but before the start of the season, the manager decided to platoon the rookie with veteran outfielder Bill Cunningham in center field. When asked about his rookie outfielder, McGraw insisted that O’Connell was not a disappointment. “He’s a good ballplayer, make no mistake about that,” McGraw said. “He’s a patient player and will develop quickly, because he’s an earnest and sincere worker.”15

When the Giants opened the 1923 season at Boston on April 17, O’Connell was the team’s starting center fielder, batting seventh in the lineup. He went 1-for-4 (a single) in his major-league debut, hit a triple the next day, and got another hit and stole a base the day after. When the Braves started a left-hander in the fourth game of the series, O’Connell went to the bench, but returned to the starting lineup the next day and went 0-for-4. The rookie outfielder then missed a week due to illness, but when he recovered, he was back in the starting lineup and pleased the hometown fans in his first game at the Polo Grounds. “The $75,000 Californian belted a single between first and second in the second inning and lined a sharp base hit to left in the sixth – not a bad day at the bat,” praised a New York Times sportswriter.16

O’Connell then slumped, going 3-for-26 in his next eight games to drop his batting average to .182. On May 8, he broke out of his slump by slamming a triple in his first career at-bat against Pete Alexander at the Polo Grounds. He could have safely made it to the plate on the hit had he been watching third-base coach Hughie Jennings, who made “semaphore signals,” reported a sportswriter. “So that was Alex the Great,” O’Connell said when he reached third base.17

On May 20, he had his first big day at the plate by going 4-for-5 and knocking in three runs before 42,000 at the Polo Grounds. Four days later, he produced a three-hit game to lift his batting average to .259. On May 27, O’Connell hit his first major-league home run, a three-run blast. The next day he hit a “whistling home run into the lower right field stand,” against Brooklyn pitcher Burleigh Grimes.18 On May 30, “O’Connell chose the fifth inning in which to uncover his third home run in the last few days,” reported a sportswriter.19 At Philadelphia on June 1, O’Connell hit another home run. He added three doubles to boost his average over .300. In addition, he drove in six runs and made eight putouts – it was the “first bulging day of his career under the big tent, and [he] bore considerable resemblance to a $75,000 beauty as advertised.”20

After his big day, O’Connell slumped and was eventually relegated to the bench. On June 19, he stole home, and on July 4 he hit his fifth home run. After a hitless day on July 8, O’Connell was benched and saw limited action. However, he did have one more highlight before the end of the season. During an infrequent start on August 26 at home against the Cubs, he came to the plate with one out in the bottom of the ninth and the Giants trailing, 3-1. He hit “a nice home run of the type so often seen at the Polo Grounds, a lofty drive along the right field line that landed in the upper tier.”21 Later that inning, New York proceeded to win, 4-3, on Jack Bentley’s two-run homer.

O’Connell finished his rookie season at .250/.351/.373 for the National League pennant winners. He got into two World Series games, as a pinch-hitter, getting hit by a pitch and striking out. The Giants lost in six games to the crosstown Yankees.

When O’Connell reported for spring training in 1924, it was noted that he looked better than the year before. “O’Connell is heavier and in better health,” noticed a New York sportswriter. “The $75,000 beauty says he is stronger and fitter than last year, when he was sick much of the time.”22 After one week of training for the new season, McGraw promised better things for the young outfielder. “O’Connell this year is the O’Connell that we expected to see last spring,” said the Giants manager. “He has finally found himself and he is playing now as he did on the coast.”23

When the season started, however, O’Connell wasn’t in the starting lineup. Through the first three months of the season, he appeared in just 20 games, primarily as a pinch-hitter, pinch-runner, or a late inning substitute. In mid-June, there was speculation that O’Connell might break into the starting lineup when Giants outfielder Billy Southworth fractured a small bone in his hand and Irish Meusel went into a batting slump, but it didn’t happen.

Moving into August, McGraw finally turned to O’Connell. “Jimmy O’Connell took Southworth’s place for one of his infrequent appearances in the Giants [starting] lineup,” wrote a New York sportswriter.24 “The former Pacific Coast League star was cheered liberally as he took his place at the plate in the opening inning but he replied with a feeble grounder to the pitcher. Later, he made two singles that aided in the scoring,” reported the New York Times.25

McGraw kept O’Connell in the starting lineup for one more week, and the 23-year-old outfielder responded by going 10-for-35 before returning to the bench. In September, McGraw made O’Connell a starter again. During a doubleheader on September 2, he went 6-for-9 to lift his batting average to .347. On September 23, “O’Connell came up, hit at the first good one, and lifted it into the right field grandstand upper apartment,” for his first home run of the season.26 Five days later, in the final Giants game of the 1924 season, O’Connell went 3-for-5 and hit another home run in what proved to be his final major-league game. His 1924 season stats of .317/.388/.452 were an improvement from the year before; they brought his brief big-league career figures to .270/.361/.396 with eight home runs and 57 RBIs.

On September 27, the day before O’Connell concluded his second season in the majors, the Giants were one win away from clinching their fourth consecutive National League pennant. He was in the team’s clubhouse when, according to O’Connell, Giants coach Cozy Dolan approached him and said, “If you can get [Heinie] Sand [Phillies shortstop] to let down in today’s game, there’s five-hundred [dollars] in it for him.” A confused O’Connell – who knew Sand from when they played against each other in the Pacific Coast League – asked where the money was coming from; Dolan told him that the Giants were going to pitch in and make up a purse.

Shortly after that conversation with the coach, Giants center fielder Ross Youngs entered the clubhouse, walked over to O’Connell, and asked if he had spoken with Dolan. O’Connell told him he had. “You go ahead because it’s all right,” said Youngs. A few minutes later, Giants second baseman Frankie Frisch spoke with O’Connell and told him to tell Sand if he threw the game, he could have anything he wanted. Later, when on the field and standing by the batting cage during batting practice, Giants first baseman George Kelly encouraged O’Connell to speak to Sand. Hearing from a coach and three teammates made O’Connell assume that it was okay for him to talk to Sand.27

O’Connell followed orders and approached the Phillies shortstop. “How do you feel about the last two games, Heinie?” O’Connell asked.

“Fine, we’ll beat your club,” replied Sand.

“It will be worth $500 to you if you don’t bear down too hard,” said O’Connell.

“What do you mean?” asked Sand.

“You know what I mean,” answered O’Connell, who then assured that Cozy Dolan was in on it. Sand asked if the rest of the Giants knew. “Sure,” replied O’Connell. “Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs understand.”

“Tell your friends that there is not enough money in New York to bribe me and they are in for a licking today,” replied an angry Sand, who then walked away and immediately reported the offer to Phillies manager Art Fletcher.28

Later that day, after the Giants won, 5-1, Fletcher phoned National League president John Heydler and requested a breakfast meeting the following morning to discuss an important matter he felt he could not discuss on the telephone. The following morning, Heydler, Fletcher and Sand met; after breakfast, Heydler phoned Commissioner Landis, who was preparing to travel from Chicago to Washington for the start of the World Series. The Judge immediately changed his plans and headed to New York City. Shortly after arriving and checking into his suite at the Waldorf Astoria, his first act of business was to confer with Heydler and summon Heinie Sand. Following his chat with the Philadelphia shortstop, he phoned Giants owner Charles Stoneham and manager McGraw, who said they were unaware of O’Connell’s actions. He then summoned O’Connell.

Jimmy O’Connell arrived at the Waldorf Astoria and went directly to the commissioner’s suite. He would later recall that it was ordinary-looking, with a davenport and table in a sitting room. Landis sat on the davenport; O’Connell sat on a chair across from the commissioner. Landis asked some questions; O’Connell didn’t deny Sand’s story — in fact, he admitted that he had made an offer in return for helping the Giants win.

“Do you understand, O’Connell, that as a result of what you are telling me, you will be expelled from baseball?” Landis said while wagging a finger at the young ballplayer. By this time, O’Connell understood that what he had done was wrong and knew he was in trouble. “Yes, Judge; I know that,” he replied.29

O’Connell then mentioned that he was not alone and mentioned Dolan and the three teammates. Landis responded by summoning the persons mentioned by O’Connell and ordered a stenographer to be present. After the stenographer, the coach, and the three ballplayers arrived,

Cozy Dolan was the first to be questioned. When Landis asked about the conversation, Dolan replied that he could not recall it. “You can imagine that I was considerably surprised when Dolan said he didn’t remember any such conversation,” O’Connell, who was present for the questioning, later said.30 “You can’t recall it?” asked Landis. “Today is Tuesday. The conversation which I am asking you about between you and O’Connell, O’Connell says took place at the clubhouse at the Polo Grounds last Saturday. That is three days. And you can’t recall such a conversation?” Landis kept asking and clarifying what O’Connell said, and Dolan kept saying he couldn’t recall. “That’s the best answer you can give, just that you can’t remember it?” asked a now angry Landis. “I don’t remember,” said Dolan.31

Ross Youngs, next to be interrogated, denied talking to O’Connell. “When is the first you heard of this?” asked Landis. “Just now, when you called me in,” replied Youngs. “That talk between him and Dolan that I am asking you about he said occurred last Saturday. This is Tuesday, only three days after,” said Landis. “It is news to me,” said Youngs.32

Finally came Frisch. “Mr. O’Connell’s statement was that he told you that Dolan had told him to see Sand and offer him five hundred dollars if he would ‘not bear down on us’ today,” Landis said. “What did you say Frisch said to you after you told him what Dolan said to you?” Landis asked O’Connell. “Give him anything he wants,” replied O’Connell. “I never said that. That’s news to me,” said Frisch.33 During the discussion, Frisch said that there is “always a lot of kidding going on every bench.”34

“Do you remember Mr. O’Connell this last Saturday coming up to the cage when you were at batting practice and you asking him a question?” Landis asked George Kelly.

“About what?” asked Kelly.

“About Sand,” clarified Landis.

“No sir,” replied Kelly.

“And you are dead sure you did not ask him any questions about Sand?” asked Landis.

“Not a thing about Sand,” answered Kelly.35

Later that evening Landis called the investigation complete and made an announcement: “Player O’Connell and coach Dolan of the New York National League Baseball Club have been placed on the ineligible list.” Youngs, Frisch, and Kelly were exonerated and permitted to play in the World Series.36 “They were dumb,” John McGraw said about O’Connell and Dolan.37

Back in California, O’Connell’s former manager said he was shocked. “I can’t believe he was mixed up in such a thing,” said Charlie Graham.38 Also talking to reporters in California was O’Connell’s father, who wept as he spoke. “Jimmy has always been such a good boy, and he is too good a sport to do such a thing unless he was dominated by others. I don’t believe he is entirely to blame,” said Mr. O’Connell.39

“They were all in on it,” insisted O’Connell, who said he was being made the “goat.” When asked why he went through with it, his answer was, “I didn’t know what else to do.”40

Shortly after the completion of the 1924 World Series, O’Connell, wondering what his future would be in professional baseball, headed back to California. On November 18, 1924, he got his answer when a letter naming blacklisted ballplayers was sent by Judge Landis’s secretary, Leslie O’Connor, to every major-league baseball team. O’Connell and Dolan were among the 11 names in the letter. “Unless something develops through court action, the names of O’Connell and Dolan are likely to pass out of baseball completely,” reported Chicago Tribune sportswriter James Crusinberry.41

“The whole thing, in my opinion, was a cruel practical joke on the part of Dolan,” Cubs owner William Wrigley said one year later. “He figured O’Connell for a kid and thought he was putting over a clever joke, never dreaming an investigation would come out of it.”42

Landis was asked to reconsider his decision but stood firm. “If I reinstate O’Connell, I must reinstate other offending players, and that would be a hard thing to explain,” said the commissioner.43

In the winter of 1925, O’Connell hung around with members of the San Francisco Seals and joined them in playing exhibition basketball games. When word was received about O’Connell, he was formally dismissed from the California basketball league in which he was playing. When spring came around, O’Connell hoped to wear the Seals uniform and join them in spring training, but this was also disallowed.

Following a season away from the game, O’Connell signed with a team in the Copper League, an outlaw league based in the Southwest that employed various blacklisted players, including notorious “Black Sox” Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, and Chick Gandil. After the season, he returned to San Francisco and worked as a stevedore.

He continued to play in New Mexico for the next several years. Among other things, he led a barnstorming team called “Jimmy O’Connell’s All-Stars.”

O’Connell and his wife had no children.44 In 1933 they moved to Bakersfield, California, where he went to work for the Richfield Oil Company. He advanced to the level of public relations executive.

In 1942, O’Connell took a job as a general storekeeper for a liquor store, a position he held until his death in Bakersfield in 1976.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Photo credit: Jimmy O’Connell, courtesy of Jacob Pomrenke.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

For more on Jimmy O’Connell’s life and career, featuring reminiscences from his great-niece, Lois Maffeo, see SABR member Gary Cieradkowski’s story “Jimmy O’Connell: The Other Side of a Scandal” (https://infinitecardset.blogspot.com/2016/02/213-jimmy-oconnell-other-side-of-scandal.html).

Notes

1 New York Telegram Mail, March 16, 1925, in the Jimmy O’Connell file at the Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York.

2 Ed R. Hughes, “Seals Should Have Had Two Wins Yesterday,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 28, 1919: 11.

3 Ed R. Hughes, “Blackwell to Quit Baseball, he Wires Seals,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 16, 1920: 10.

4 “Chicago offers $10,000 for O’Connell,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 3, 1920: 11.

5 Ed R. Hughes, “Seals Wake up and Beat the Portland Gang,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 3, 1920: 10.

6 Abe Kemp, “A Brilliant Future is due to Jimmy O’Connell,” San Francisco Bulletin, July 23, 1921: 20.

7 Kemp, “A Brilliant Future is due to Jimmy O’Connell.”

8 Kemp, “A Brilliant Future is due to Jimmy O’Connell.”

9 R.J Kelly, “McGraw Elated over O’Connell and Groh Deals,” New York Tribune, December 9, 1921: 16.

10 “O’Connell signs up with San Francisco,” New York Times, February 19, 1922: 8-1.

11 “Jimmy O’Connell Out of S.F. Lineup,” Oakland Post-Enquirer, October 2, 1922: 7.

12 W. B. Hanna, “Giants Holdout Colony is Reduced to a Quartet when Rawlings Signs his 1923 Contract,” New York Tribune, March 4, 1923: 16.

13 “O’Connell Makes Impressive Debut,” New York Times, March 4, 1923: 9-1

14 W.B. Hanna, “Jim Kernan Drives Out First Home Rrun in First Practice Game at San Antonio,” New York Tribune, March 7, 1923: 12.

15 “O’Connell Will be Alternate Fielder,” New York Times, March 31, 1923: 9.

16 “Caught at the Plate,” New York Times, April 28, 1923: 10.

17 “Giants Defeat Cubs in First of Series,” New York Times, May 9, 1923: 15.

18 W.B. Hanna, “Robins Beat Giants’ Winning Streak, Taking in Free-hitting contest, 8-7,” New York Tribune, May 29, 1923: 12.

19 W.B. Hanna, “Giants Gain on Even Break with Robins,” New York Tribune, May 31, 1923: 13.

20 W.B. Hanna, “O’Connell’s All-Around Work is Feature in Champion’s Victory,” New York Tribune, June 2, 1923: 14.

21 John Kieran, “Rally in Ninth Wins for Giants over Cubs 4-3,” New York Tribune, August 27, 1923: 12.

22 “Irish Meusel, George Kelly, Joe Oeschger, Jimmy O’Connell, and Walter Jones Reach Sarasota,” New York Herald Tribune, March 1, 1924: 12.

23 “Three More Giants Sign for M’Graw,” New York Times, March 7, 1924: 12.

24 W.B. Hanna, “Giants Easily Defeat Cubs by 10 to 2,” New York Herald Tribune, August 4, 1924: 12.

25 “Caught at the Plate,” New York Times, August 4, 1923: 8.

26 W.B. Hanna, “Giants Gain in Race by Defeating Pirates, 5-1,” New York Tribune, September 24, 1924::21.

27 “O’Connell, Confession, Says He is the ‘Goat’ in Bribery Plot.” Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, October 2, 1924: 1.

28 Heinie Sand, “Sorry his Old Pal to Blame,” Washington Herald, October 3, 1924: 3.

29 J.G. Taylor Spink, Judge Landis and Twenty-Five years of Baseball (New York; Thomas Y, Crowell, 1947), 130.

30 Telegram Mail, March 16, 1925, in the Jimmy O’Connell file at the Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York.

31 New York Herald Tribune, January 1, 1925, in the Cozy Dolan file at the Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York.

32 New York Herald Tribune, January 1, 1925.

33 New York Herald Tribune, January 1, 1925.

34 Spink, Judge Landis, 133.

35 “Landis Reveals Testimony Taken in Bride Scandal,” New York Times, November 1, 1925: 9-1.

36 Universal Service, “O’Connell Confesses Offering $500 to Throw Game,” Washington Herald, October 2, 1924: 1.

37 “’They Were Plain Dumb,’ Declares McGraw,” Washington Post, October 3, 1924: page 3 in Sports.

38 “Jimmy O’Connell’s Former Manager Stands by Him,” Washington Post, October 3, 1924: 8.

39 “O’Connell is the Goat, Father Declares,” Washington Herald, October 5, 1924: S-3.

40 “O’Connell Says he Thought all Were in on Scheme,” Washington Evening Star, October 2, 1924: 1.

41 James Crusinberry, “O’Connell, Dolan, Added to Roster of ‘Black Sox,’” Chicago Tribune, November 19, 1924: 23.

42 “Cubs Owner Makes Plea for O’Connell,” New York Tribune, March 24, 1926: 18

43 “Landis Firm in Banishing O’Connell,” Washington Post, January 19, 1926: 14.

44“Obituary Notices: O’Connell, James Joseph,” The Bakersfield Californian, November 13, 1976: 19.

Full Name

James Joseph O'Connell

Born

February 11, 1901 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

Died

November 11, 1976 at Bakersfield, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.