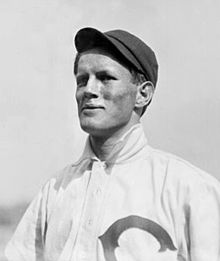

Blaine Durbin

Blaine Durbin had a meteoric rise through the bush leagues in the first decade of the 20th century. It brought the lefty pitcher to the attention of several big-league teams, including Frank Chance’s legendary Chicago Cubs dynasty. Yet Durbin’s story mirrors countless others: a phenom whose career fizzled out, promise left unfulfilled. He pitched in just five games at the top level, as a 20-year-old rookie in 1907. Overall, he made just 32 big-league appearances through 1909, mostly as an outfielder and pinch-hitter.

Blaine Durbin had a meteoric rise through the bush leagues in the first decade of the 20th century. It brought the lefty pitcher to the attention of several big-league teams, including Frank Chance’s legendary Chicago Cubs dynasty. Yet Durbin’s story mirrors countless others: a phenom whose career fizzled out, promise left unfulfilled. He pitched in just five games at the top level, as a 20-year-old rookie in 1907. Overall, he made just 32 big-league appearances through 1909, mostly as an outfielder and pinch-hitter.

Durbin’s career was in many respects frustrating. He was a part of three World Series winners, but lack of playing time denied him the opportunity to develop as a player at a point in his career when he should have been playing every day. He might never have reached the heights that had been predicted for him when he first arrived in Chicago, but he would have doubtlessly been better off on a lesser team when he reached the majors. That would have let him develop in a slower-paced environment.

Blaine Alphonsus Durbin was born on September 10, 1886, in Lamar, Missouri. Durbin was the fourth of five children raised by James and Clara Durbin (née St. Clair). The family was fairly prosperous owing to James’ job as a conductor for the Frisco railroad.1 By Blaine’s teenage years, the family had moved from Missouri to Fort Scott, Kansas. It was there that the young man began to be noticed on the playing field.

Durbin’s first foray into professional baseball came with the Fort Scott entry in the Class C Missouri Valley League in 1904. At the tender age of 17, the young southpaw made his debut for his hometown team as pitcher and was immediately impressive. Facing Topeka, Durbin fanned 12 Saints batters to establish a new single-game league record for strikeouts. The press noted that “his pitching was the feature, notwithstanding that it was his first game of league ball.”2

Throughout his first season, Durbin showed glimpses of promise, but he limped home to a 5-26 record. Topeka was not a very good team that season, limping home with a 37-82 record. The team was a young one, with the average age of the pitching staff being under 19 years old. As such, the club took its lumps competing against older players. The team had quality young prospects besides Durbin. Three teenaged Giants players besides Durbin eventually became major-league players. Bob Groom spent 10 years in the majors, primarily as a pitcher for Washington, winning 24 games in 1912. Bobby Byrne played 11 seasons in the majors as an infielder and was a starter on the 1909 Pittsburgh Pirates championship team. First baseman Tex Jones earned a call-up to the White Sox in 1912 before returning to the Western League. The Fort Scott Giants had talented players in 1904, Durbin included, but they were still raw.

Durbin’s 1905 campaign showed improvement. Though he again posted a losing record, this time for the Joplin (Missouri) Miners and the St. Joseph Saints of the Class C Western Association, he improved to a 13-19 mark. Still a teenager, Durbin remained a fan favorite in Fort Scott, where it was noted that he was “being pitched too frequently for a boy of his years and (was) not being coached properly.”3 In addition to his youth, Durbin was undersized at 5-feet-8 and 155 pounds. Durbin’s lack of height was constantly referred to throughout his career, but it was only an issue when he was losing games. In 1906, however, he made everyone ignore his physical stature and concentrate on his electric curveball. He caught the notice of baseball’s elite.

Durbin’s 1906 campaign began with a visit to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to try out with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He was not issued a formal invitation by the Pirates to attend spring training. Rather, he “(was) given to understand that he will be used if he appears at their spring training quarters in the South.”4 He did not make the grade that spring with Pittsburgh and spent the season again with Joplin. He emerged with a 32-8 record for the year, Durbin’s manager that season credited the development of a sharp-breaking curveball along with improved speed and control as being key in his growth as a pitcher. His confidence had also improved; it was noted that he had become “a general in the box.”5

As a result, various major-league scouts pursued him. The St. Louis Browns came calling first; manager Jimmy McAleer desired Durbin, who had become considered the “best pitcher in the Western Association.”6 Chicago White Sox boss Charles Comiskey was “after the boy” to join his team for the 1907 season.7 In the end, the best offer came from Chicago Cubs president Charles Murphy. In August, he sent a telegram to Joplin manager Louis Armstrong, and a bargain was struck for Durbin to be sold to the Cubs at the close of Joplin’s 1906 season.8

Still with Joplin, Durbin threw his greatest game shortly after signing with the Cubs. On September 4, Durbin and Elmer Meredith of the Webb City (Missouri) Goldbugs engaged in a fierce pitchers’ duel. When the game was abandoned as a result of darkness, neither team had scored a run over 20 innings. Durbin scattered six hits and fanned 12 Webb City batters.9 While the performance bolstered Durbin’s reputation as a phenom, it came at a cost. He finished the season with an arm that was “frightfully sore” as a result of the Webb City game.10 Following the season, he returned to St. Benedict’s College in Atchison, Kansas, to finish his senior year. There Durbin rested up to prepare for the monumental challenge of jumping from Class C Joplin to the recently crowned National League champions in Chicago.

Durbin began the 1907 campaign trying to win a berth with the Cubs during their spring training tour of the cities of the Cotton States League in Mississippi and Alabama. His breakthrough moment came in Mobile with a performance against Cubs’ skipper Frank Chance. In a batting practice session, Durbin spun a curve ball that broke so sharply that it caused Chance to swing and miss a pitch that hit him in the knee.11 Durbin’s performance was impressive enough to win the rookie a spot on the team.

Chance gave reporters an effusive breakdown of Durbin as he made the announcement: “Durbin has everything. His size counts against him a little, but at that he’s bigger than “Noodles” Hahn who was a great pitcher in his day. Durbin has fine speed, a curve ball with a quick break, and what I like above everything else, he has the nerve… Durbin is a ball player — every inch of him. He can hit, play the outfield and in general has baseball sense. He knows what to do any place you put him, and I consider him a strong addition to our team.”12

Chance was not the only member of the Cubs’ brass who was excited to have Durbin in the fold. Charles Murphy told reporters that he would refuse offers of up to $10,000 for Durbin, stating that he was the “most promising youngster that has broken into the big leagues in the last ten years.”13 Durbin pitched for the Cubs prospects in a spring exhibition against the team’s regulars, beating the defending pennant winners, 3-2. He scattered two hits and no runs in five innings of work, and left Chance, Murphy, and umpire Jimmy Ryan “in an ecstasy of joy over the good work of the lad.”14 On the basis of his strong showing, Durbin went north with the Cubs to open the 1907 season as one of the most heralded prospects in the game.

Durbin’s first appearance in Chicago came in a relief role against Cincinnati on April 24 at the West Side Grounds. He entered the game in relief of Jack Taylor in the sixth inning with the Reds up, 9-2. The young southpaw went the final three and a third innings, allowing five hits and three runs while managing to strike out two Reds batters. In two at-bats, Durbin also singled to notch his first major-league hit. The rough introduction to the major leagues did little to dissuade Chance or the other power brokers in the National League about Durbin’s promise as a player. A few days later in St. Louis, Chance told reporters that “scarcely a day passes that I don’t get a query from someone as to where there is any chance of getting (Durbin). It is no wonder that half the National League clubs refused to waive on him when we asked waivers on all our new players.”15 This praise proved double-edged for Durbin.

In early May, the Cubs attempted to farm out Durbin to the minor leagues and asked waivers on him. Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss put in a claim for Durbin to block the transfer.16 Durbin was stuck in a no-win situation. He was too good to clear waivers and go down to the minors for some seasoning, but not good enough to crack the Cubs rotation. Few could have done so that season. Orval Overall, Mordecai Brown, Carl Lundgren, Jack Pfiester, and Ed Reulbach gave the Cubs five starting pitchers with ERAs under 1.70. It wasn’t that Durbin wasn’t well thought of by the Cubs brass; it was simply that he was a rookie on a team with one of the greatest rotations in the game’s history.

In June, the Cubs once again tried to farm out Durbin, this time to Omaha of the Western Association. This time, the Boston Doves blocked the move, and the Cubs decided to keep Durbin in Chicago for the rest of the season “whether (he plays) a game this season or not.”17

Durbin appeared in 11 games for the Cubs in 1907; six came after the team had already made their World Series reservations. He appeared twice as a right fielder in a July series against the Cardinals. Chance viewed the speedy Durbin as “a second Willie Keeler,” indicating that the rookie’s future in the game would be secured by his hitting prowess in case the pitching didn’t pan out.18 Durbin’s first start as a pitcher with the Cubs came on September 22 in the second game of a home doubleheader against the Doves. In the first game, the Cubs won, 8-7, to clinch no worse than a tie for the pennant. For the nightcap, Chance “listened to the pleadings of the rooters” and cleared the bench to try out his young prospects. Durbin was given the ball.19

He fanned Izzy Hoffman to start the first inning, then hit Fred Tenney on an 0-2 count. He coaxed Bill Sweeney to ground to short, but Joe Tinker’s throw was mishandled by first baseman Del Howard to put two men on with one out. The next batter, Ginger Beaumont, cleared the bases with a two-run triple; Beaumont came around to score on a Claude Ritchey single to make it 3-0 before Durbin retired the side. He settled in after that, throwing a shortened seven-inning complete game and allowing only five hits in total in a 4-2 defeat. Durbin came up to bat in the seventh inning representing the tying run with two outs after Tinker had singled. However, Tenney fooled the Cub shortstop with the hidden ball trick to end the game.

Though the Cubs lost, “no youngster ever received a warmer welcome from the fans than Durbin.”20 Reporters noted that the five Cubs errors on the day were the reason for the defeat and that “he had received some of the most discouraging support ever handed out to a young man.”21 Durbin received more playing time down the stretch but did not feature in the World Series as the Cubs defeated the Tigers to capture the title.

That offseason was an eventful one for Durbin, who arrived back in Fort Scott with a check for $2,343.10 — a full World Series winner’s share.22 Durbin put the money to work. He purchased a 55-acre farm near Miami, Oklahoma, and opened a cigar store near there where locals could come hear the youngster spin tales of his exploits with the Cubs.23 One tale he likely told quite often was how he had earned a nickname among the Cubs after the season ended.

It originated in Chicago shortly after the World Series had ended. Actress Lillian Russell, “an ardent base ball fan and admirer of the Cubs,” put together a special show at a Chicago theater to recognize the team members in the audience.24 As a token of thanks, the team brought a bouquet to the theater to present to Russell at the conclusion of the show. Durbin had his own ideas. He snatched the bouquet and made his way to the stage, where he presented the flowers to Russell presumably while making a pass at the actress. The team immediately dubbed the young pitcher “Danny Dreamer” for his attempt and the name stuck with him for the remainder of his career.25 The label “Kid” which later became attached to him was not ever used in the media either in Chicago, Fort Scott, or nationally. He was universally known either by his given name or true contemporary nickname.

Durbin began the 1908 season with the Cubs in much the same predicament that he had faced the year before. The defending World Series champions attempted to send Durbin to the minors for seasoning, but again he couldn’t clear the waiver process. Chance gave the press a matter-of-fact statement regarding the situation in late April after announcing that Durbin was to remain with Chicago for the season.

“I have all kinds of offers for Blaine Durbin and I would like to send him to the Eastern League or American Association where he could get plenty of work and at the same time be where I could get him if needed. But Durbin cannot get out of the major leagues. Several clubs want him and they refuse to waive when asked … The result is, I dare not ask waivers on Durbin, for then I’d lose him surely, and I want him with this club.

Durbin is going to make a grand little ball player, but I can’t afford to break up our combination right now. The inequity of the waiver rule is clearly shown in Durbin’s case, but still I admit something had to be done to stop the abuse of it.”26

Durbin was thus facing a second consecutive season as a benchwarmer. In addition to the great pitchers ahead of him in the rotation, Durbin’s opportunities were further limited amid the closeness of the 1908 pennant race. While the Cubs of 1907 had left the league in their wake, the 1908 team was engaged in a three-way battle with the Pirates and the Giants. In fact, Durbin would never again take the mound in a major-league game. His future with the Cubs was in the outfield, and the young southpaw was given a chance to secure a spot on the team with his bat.

In early July, Cub center fielder Jimmy Slagle joined the growing ranks of injured players and Chance tabbed Durbin as his replacement. Between July 6 and July 13, Durbin was the regular in center for the Cubs. He played eight consecutive games in place of Slagle and did well. Over this span, he had a .269 batting average and a .387 on base percentage. These numbers were no threat to the league leaders, but they were above the combined team average for Chicago that season, indicating that in reserve Durbin had more than held his own. His work in the field drew positive reviews as well. Durbin’s “great catch of Al] Burch’s sizzling liner” thwarted a Brooklyn rally in a July 9 win against the Dodgers.27

Despite this, Durbin was limited to three pinch-hitting and defensive replacement appearances over the next week, and July 22 marked the final time he appeared in a box score for the Cubs. Though it appeared that he had done well on the field in an extended trial, something had gone wrong. Durbin’s promising career was about to take a turn for the worse.

The first outward sign that Durbin was falling into disfavor with the Cubs came immediately following the 1908 World Series. The Cubs players were entrusted with dividing up shares of the money allotted to the winning team, and even though Durbin was on the active roster for the entire season, he was voted only a one-third share of the spoils, as were pitcher Rube Kroh and trainer Bert Semmens.28 Durbin and Kroh were enraged by this perceived betrayal. Kroh had spent the season in the minors and had agreed to join the Cubs for the stretch run only on the condition of getting a full Series share. Durbin was reportedly stunned to learn that though Chance had stuck up for him, the players denied his right to equal pay after telling him that “you don’t belong to the regulars. You’re only a volunteer.”29

It was true that Durbin did not play very much, yet he had played more than other players such as Doc Marshall who had received a full share. In addition, he had filled in admirably when injuries had ravaged the Cubs lineup in July. Durbin did not take this slight good-naturedly. He wrote to Cubs President Murphy asking to be traded to a team that would play him. Further, he lodged a formal complaint with the National Commission against the Cubs for the shortfall in his World Series share and he refused to sign his 1909 contract sent to him from Chicago.30 The Cubs decided they had had enough of Durbin, and days later they traded him to Cincinnati along with Tom Downey for John Kane.

After the trade, Frank Chance made his feelings clear on Durbin’s departure, stating that “Durbin wasn’t satisfied here and we are not going to have any dissatisfied ones on our list.”31 The rift was further clarified in a story that was related by reporters in the weeks following the trade. According to reports, Chance was looking for an opportunity to get Durbin a mound appearance in late 1908 and saw a chance as Carl Lundgren was struggling. Chance called to the bullpen for Durbin to warm up and enter the game in relief. Instead of leaping at the chance to make up for two years of lost time, Durbin declined the opportunity, stating, “I have a toothache.”32 Chance’s exact reply is lost to the ages, but those present reported that the Peerless Leader was enraged with Durbin — and that Danny Dreamer was effectively done as a member of the Cubs.

For his part, Durbin announced that he was glad to see his time in Chicago come to an end. He was quoted, “The two years I put in with the Chicago Cubs seem like a nightmare to me now … I begged for a chance to show what I could do, but manager Chance showed me that it was next to impossible to try me out with so many star pitchers and outfielders on the team. It finally got so when anyone asked me who won, I replied ‘THEY’ as I hardly counted myself a member of the team.”33

Sadly for Durbin, his tenure with the Reds offered him little chance to prove his worth to the team. He was limited to six pinch-hitting appearances through mid-May, going 1-for-5 with a walk and a run scored. It was his only hit with the Reds; shortly thereafter he was dealt for a second time. This time, a familiar suitor finally managed to acquire Durbin: the Pittsburgh Pirates.

On May 27, 1909, the Pirates swapped Ward Miller and cash to Cincinnati for Durbin. Though the Pirates had long desired Durbin, he was being placed in another no-win situation. On the day of the trade, reporters noted that “it is very likely that he will receive as poor encouragement here as he did in Chicago and Cincinnati.”34 The reporters’ assumptions proved to be correct. The Pirates were in the thick of a pennant race, and there was no spot in the lineup or the rotation for an unproven talent. Durbin’s only appearance on the field with Pittsburgh was a noteworthy one, though not for anything he did. He appeared in the June 30 home game against the Cubs as a ninth-inning pinch-runner in a 3-2 loss to Chicago. It was the first-ever game for the Pirates at Forbes Field — but Durbin’s last at the major-league level. Immediately following the game, he was sold to the Scranton (Pennsylvania) Miners of the Class B New York State League. After three years of languishing on big-league benches, Durbin was going to be a regular player again.

Durbin’s stint with Scranton went well in one respect. He “(gave) a fine exhibition of the national game in the field” with the Miners.35 His batting average, though, left something to be desired. In 66 games as an outfielder, Durbin hit a scant .219 for the season. After finishing the season with Scranton, he returned home to marry Alta Green of Miami, Oklahoma, where he had several business interests.

The following January, Scranton sold Durbin to the Western League’s Omaha team, though he was kept on the Pirates reserve list by manager Fred Clarke.36 Durbin did not report to Omaha, though. He decided to quit Organized Baseball. He was reportedly “making more money … and having a better living than he had at any time while playing ball.”37 In addition to his mining interests in Miami and his cigar store, Durbin was part of a family manufacturing business which had been started by his brother Votaw. Their product was a revolutionary new train coupler which was initially capitalized through a stock sale totaling $1.5 million.38 For a man who had just months earlier sued the Cubs for $500, money was no longer a concern.

Durbin still had the itch to play baseball and founded a semipro team, the Miami Indians, playing against town teams. His association with the Cubs drew crowds to see the local player who had played in the majors. It was a far cry from playing at the West Side Grounds, but rather than sitting on the bench, Durbin was the featured attraction.

The following season, Durbin played in the Western League with Omaha and Topeka as an outfielder. In 1912 he pitched in 14 games with Oakland in the Class AA Pacific Coast League. After that year, however, he never again played in Organized Baseball, appearing instead for town teams in independent leagues. He did have an opportunity to participate in the majors one final time in 1914 when former teammate Mordecai Brown, the manager of the Federal League’s St. Louis Terriers, offered him a place on his roster. Durbin declined, opting instead to continue playing Sunday ball with the Oroville Olives in northern California.39 It was the last time Durbin would be associated, even peripherally, with a major-league baseball team.

Durbin, his wife, and their four children (James, Melba, Annadean, and Catherine) eventually relocated to the St. Louis area, where he worked as a salesman for the family coupling foundry. Durbin’s wife was in declining health during her fourth pregnancy, and a month after delivering the couple’s fourth child, she died on September 12, 1918.40

Durbin remained in St. Louis to raise his family, living there for most of his remaining days. The former phenom died from a coronary thrombosis on September 11, 1943, in Kirkwood, Missouri at the age of 57.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author utilized www.baseball-reference.com for statistical information and www.ancestry.com for family records.

Notes

1 “Young Ballplayers,” Salina (Kansas) Semi-Weekly Journal, August 10, 1906: 3.

2 Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, April 11, 1904: 2.

3 Fort Scott (Kansas) Tribune, May 30, 1904: 3.

4 Fort Scott (Kansas) Republican, March 29, 1906: 1.

5 “Cubs Have A Find In Blaine Durbin,” Muncie (Indiana) Evening Press, December 31, 1906: 2.

6 “Want Blaine Durbin,” Fort Scott Republican, June 9, 1906: 4.

7“A Remarkable Record,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Post, August 1, 1906: 6.

8 “It’s A Sure Go,” Fort Scott Tribune, August 4, 1906: 4.

9 “A Record Broken,” Sedalia (Missouri) Democrat, September 5, 1906: 8.

10 “Durbin Pitches Sunday,” Fort Scott Republican, September 28, 1906: 1.

11 “Sports and Games,” Waterloo (Iowa) Courier, March 20, 1907: 5.

12 Same as above.

13 “Blaine Durbin Not for Sale,” Oklahoma City Times, April 8, 1907: 1.

14 “Blaine Durbin Is a Wonder,” Kansas City Times, April 20, 1907: 10.

15 “Touts Durbin a Sure Comer,” Pittsburg (Kansas) Press, April 27, 1907: 5.

16 “Journals Sporting Section,” Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, May 11, 1907: 3.

17 “The Fate of Blaine Durbin,” Fort Scott Tribune, June 4, 1907: 3.

18 “B. Durbin Is a Hitter,” Cherokee (Kansas) Sentinel, July 5, 1907: 4.

19 “Cubs Nearly Win Second Pennant,” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1907: 10.

20 “Cubs Nearly Win Second Pennant.”

21 “Cubs Nearly Win Second Pennant.”

22 “May Play an Outfield,” Fort Scott Tribune, October 23, 1907: 4.

23 “Put It in Farm,” Pittsburg (Kansas) Headlight, December 11, 1907: 4.

24 “Story of the Way Durbin Got Name Danny Dreamer,” Omaha Bee April 13, 1911: 4.

25 “Story of the Way Durbin Got Name Danny Dreamer,”

26 “Cubs’ Pruning Process Is Finished by Chance,” Pittsburg Press, April 21, 1908: 14.

27 Richard G. Tobin, “Cubs Come Up from Behind and Defeat Dodgers in Tenth,” (Chicago) Inter Ocean, July 9, 1908: 10.

28 I.E. Sanborn, “Luscious Melon Carved by Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, October 17, 1908: 6.

29 “Kroh and Durbin Leave in a Rage,” Pittsburg Press, October 20, 1908: 16.

30 “He Refused to Sign Up,” Fort Scott Republican, February 18, 1909: 1.

31 “Cubs Secure Johnny Kane,” Chicago Tribune, February 19, 1909: 6.

32 “Draws Pay for Two Years, Has Toothache When Wanted,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald, April 5, 1909: 2.

33 Charles H. Zuber, “A Durbin Story,” Topeka (Kansas) Capital, April 7, 1909: 2.

34 “Ward Miller to Join Reds at Cincinnati on Sunday,” Pittsburg Press, May 28, 1909: 26.

35 “Sidelights on the Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 31, 1909: 18.

36 “Scranton Sells Durbin,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, January 28, 1910: 10.

37 “Durbin Quits Base Ball,” Iola (Kansas) Register, February 23, 1910: 3.

38 “A Safe Investment,” Fort Scott Tribune, February 15, 1910: 5.

39 “Federals After Durbin, Sacramento Bee, April 8, 1914: 10.

40 “Death of Mrs. Durbin,” Miami Record-Herald, September 20, 1918: 7.

Full Name

Blaine Alphonsus Durbin

Born

September 10, 1886 at Lamar, MO (USA)

Died

September 11, 1943 at Kirkwood, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.