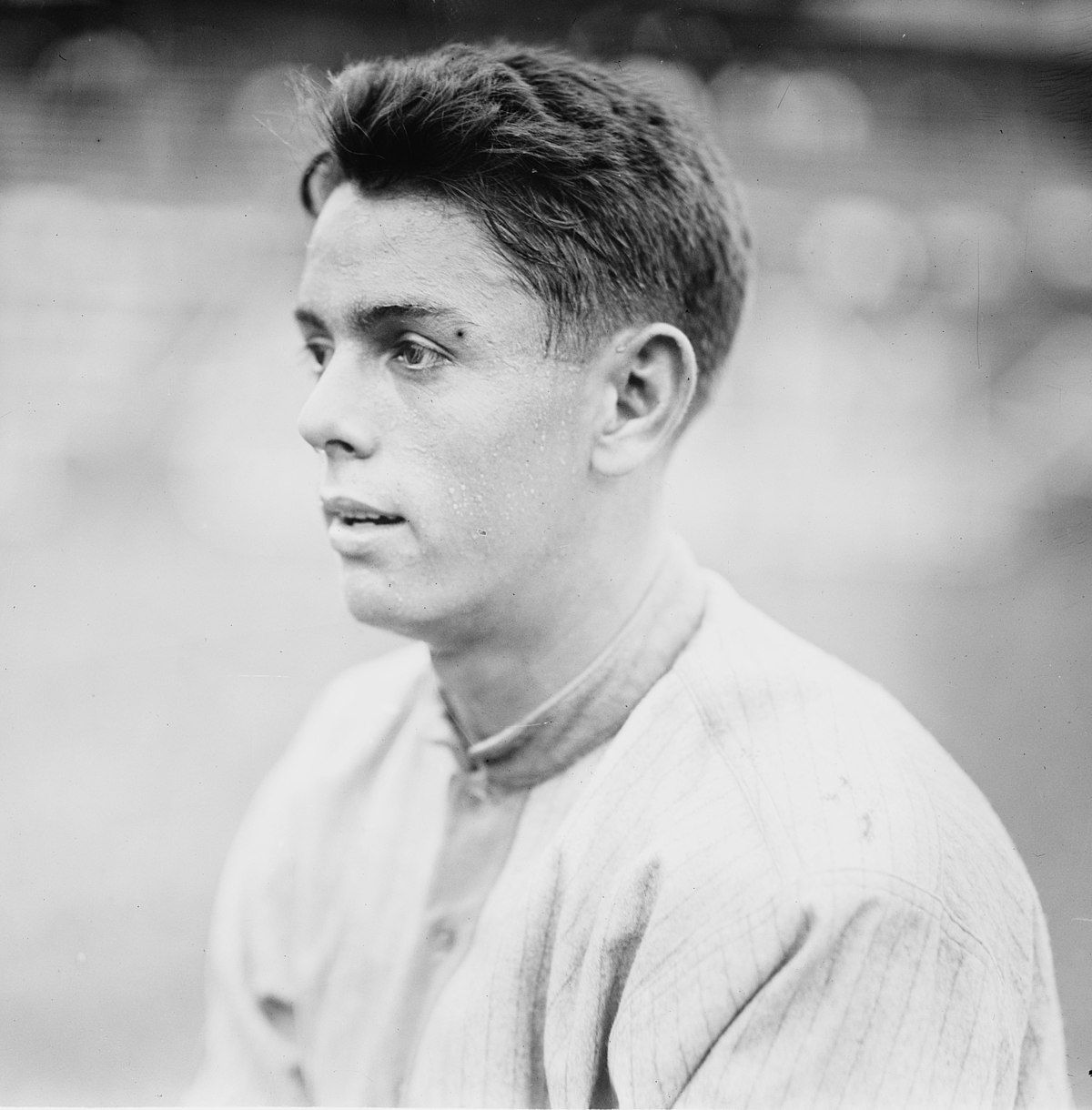

Merito Acosta

One of the main attractions of the Louisville Slugger Museum is its Signature Wall showing the names and signatures that have been branded on bats for hundreds of baseball players dating back to the beginning of the practice. Among the names of plaques featured from the 1920s is Baldonaro Acosto. The incorrectly spelled name on his plaque does not indicate that at one time Baldomero “Merito” Acosta was one of the top Latin prospects in baseball.

One of the main attractions of the Louisville Slugger Museum is its Signature Wall showing the names and signatures that have been branded on bats for hundreds of baseball players dating back to the beginning of the practice. Among the names of plaques featured from the 1920s is Baldonaro Acosto. The incorrectly spelled name on his plaque does not indicate that at one time Baldomero “Merito” Acosta was one of the top Latin prospects in baseball.

Acosta was one of the first Cubans to make the jump to the major leagues in the United States, which he did in 1913 as a youth of 17. The little outfielder (5-feet-7 and 140 pounds) never lived up to his lofty prospect status in the majors. He hit a punchless .255 in 180 games through 1918, mainly with the Washington Senators. However, he did enjoy a successful career as a popular minor-leaguer, playing on through 1928 in the U.S. — the last 10 seasons in Louisville.

Afterwards Acosta became one of the more influential Cubans in professional baseball, and devoted years to promoting baseball relations between the two countries, ultimately receiving the highest honor for baseball players in his native land.

Baldomero Pedro Acosta Fernández was born May 19, 1896, in Bauta, Cuba, a town located about 17 miles southwest of Havana. The nickname “Merito” is a shortened version of Baldomerito, meaning the little Baldomero, in honor of his father Baldomero Pedro Acosta Eusebio. The senior Baldomero can be found referenced in Cuban history books. He was a high-ranking officer in the in the 1895 Cuban fight for independence, and also fought in the Spanish-American War. He was later the mayor of the municipality of Marianao, a position that would be helpful throughout his son Merito’s career. The senior Acosta remained involved in political activities in the nation for years up to his death in 1943.

Merito was one of at least three children born to Baldomero and Clara Fernández Lago. One brother, Pedro, played with the Long Branch Cubans, a traveling team made up of Cuban ballplayers that was based out of New Jersey, but he later quit in order to join the Cuban military in support of his father.1

José Acosta, a Cuban pitcher of the same era who also played for Washington, is referenced in a number of places as being Merito’s brother, but this is likely not correct. José was born in Havana and does not show any connection to Baldomero Acosta in ancestry searches. And in researching articles on Merito, no mention was found of the two being related, even during International League games where they faced each other. It was more likely a general assumption that two Acostas from Cuba, who both spent time with the same major-league organization, must have been related.

Merito Acosta first gained some attention in Cuba playing as a teen in a tournament for a team from Medina, a town outside of Havana.2 From there he was recruited to play for the popular Habana Leones, or Lions (traditionally known as the Reds). As a 16-year-old rookie playing for the Reds in 1913, he caught the eye of Victor Muñoz, the sports editor for El Mundo, one of the largest newspapers in Havana.

While managing the Cincinnati Reds in 1911, Clark Griffith had been impressed with Cubans Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida. The next season Griffith moved over to the American League to manage the Washington Senators (commonly known as the Nationals at the time), and he hoped to discover more talent on the island that he could import for his new club. He developed a relationship with Victor Muñoz to help “bird dog” players in Cuba. In January 1913, based on Muñoz’s recommendation, Griffith signed Acosta, along with Jacinto Calvo of the Almendares club.3 It was reported that the senior Baldomero proclaimed a holiday in their hometown of Marianao to celebrate the signing.4

Washington, D.C. did not hold a parade in honor of Acosta’s signing with the Nationals, but there was much fanfare from Washington newspapers, and no shortage of outrageous expectations heaped on the youngster. Acosta had never been seen playing in the States, but based on reports from Cuba, the lefty outfielder was dubbed among other things “the most remarkable performer the game has ever developed when his age is taken into consideration.”5 He was considered to be as fast as Ty Cobb, and utilized a punchy hitting style that was compared to that of “Wee” Willie Keeler. The diminutive Acosta generated little power, but he had a keen eye for the strike zone and possessed “much ability with the bat, being particularly efficient when it comes to bunting.”6

Acosta made a good showing in his first major-league spring training, but it was widely accepted that at just 16 years old he was much too young to play in the big leagues and would be farmed out to a minor-league club to start the season. But when Washington broke north in April, Acosta was still on the Opening Day roster. Griffith wanted a left-handed outfield bat on the bench, and he figured that the young Acosta could get better experience being around the big-league squad versus playing in the minor leagues. Acosta batted with a hunched-over batting stance that drew several walks, and Griffith wanted to personally work with Acosta to adjust his swing and add some power to it. Griffith’s decision was probably financially motivated as well — keeping a couple of inexperienced rookies on the team would cost less than signing other players who worked their way up from the minors. “I could cite a dozen cases where players who were in the majors and were released owing to lack of experience came back at absurd prices,” said the Old Fox7

Acosta languished on the bench for nearly two months, stepping onto the field occasionally only as a base coach. By the end of May he was pleading with Griffith either to play him or farm him out. Quotes in the Washington papers attributed to Acosta were either completely literal to his broken English or were a bit embellished. “I no like sit on bench….In big league sit on bench and yell. No fun for Cuban ball player.”8 The quote may or may not have been altered a bit for the article, but it summed up Acosta’s mindset. Finally on June 5, Acosta was sent in to pinch-hit for pitcher Nick Altrock, and he reached base on his first attempt when he laid down a bunt and St. Louis Browns pitcher Roy Mitchell bobbled it for an error. At just over two weeks past his 17th birthday, Merito became the youngest player of the modern era to make a major-league debut.9 Acosta continued to be used sparingly during the season, normally for pinch-running duties or fielding substitutions. It was not until September 6 when Acosta finally achieved his first big-league hit, a pinch-hit bunt single off Yankees’ pitcher Cy Pieh. Two more bunts and an error allowed Acosta also to score his first big league run. To this day he is still the youngest Latin American player to make his debut and get a base hit in the majors.10

Acosta completed the 1913 season playing entirely for the Nationals, though he made only 12 appearances. Washington papers continued to portray him as a star in the making for the following season, but it was acknowledged that his hitting had not been ready for the major leagues. His bat seemed to warm up upon returning to Cuba, where he again played for Habana for the winter. Reports back to the States on his performance there were positive, including his being asked to join a team of Cuban all-stars, handpicked by Jake Daubert to take on his Brooklyn Superbas in a series of exhibition games in December.11

Acosta’s seasons in Washington were spotted with occasional chances to get into the regular lineup that were short-lived for one reason or another. He was inserted in the lineup early in 1914 to replace injured outfielder Danny Moeller, but he was replaced early in the next two games. Then, in just his third game, he too was sidelined after spraining his ankle. Acosta was again the beneficiary of an injury to a teammate when on July 17 Clyde Milan was hurt after colliding with Moeller in the outfield. Acosta was placed into the starting lineup, and during a three-game home stand against the White Sox, he went 7-for-13, raising his average to .258. It was an encouraging series, but the Nationals still picked up outfielder veteran Mike Mitchell on waivers after he’d been released by Pittsburgh, and Acosta returned to his bench role.

Acosta did start the final six games of the season for Griffith, but the shine was already starting to wear off his prospect status. For one thing, his average in 12 at-bats against left-handed pitching that season was only .083, not high enough for a regular in a time when platoons were not widely used. His batting against lefties was deemed bad enough that once, when forced to insert Acosta into the lineup against White Sox southpaw Reb Russell, Griffith penciled him in at the bottom of the lineup behind weak-hitting starting pitcher Jim Shaw. There was also a lingering concern about Acosta’s fielding. He was fast, possessed a good arm, and good baseball instincts, but he had difficulties playing the sun field in the left side of Griffith Stadium’s outfield. After a series of dropped flies, Washington Times columnist Bugs Baer even suggested trying Acosta at pitcher, since he had “developed quite a drop ball in the outfield.”12

From the onset of the 1915 season, it was becoming evident that Griffith considered Acosta more suited to a utility bench role. The manager even experimented with the lefthander at third base in exhibition games to see where the team could make use of him. On July 29, Griffith shook up the lineup and Acosta was again given a chance to be a starter. He made the best of the opportunity, raising his average from .233 to .298 in the span of one week. But again Acosta suffered an untimely injury, this time getting hit by a pitch on the right elbow. His batting average dipped a bit, but he played through with a bruised arm. On August 29, he was hit in the same spot by George Sisler, then a young St. Louis Browns pitcher. Acosta missed only one game, but his batting average steadily declined from there, and he finished the season at .209.

During the 1915 season, Acosta took part in an odd baseball incident. In the first game of a doubleheader on August 22, he was involved in an inning where a run scored without a registered at-bat. Facing Detroit that day, Chick Gandil and Acosta both walked to start the second inning. They each moved up a base by way of a sacrifice bunt, and Gandil scored on a sacrifice fly, but then Acosta was picked off second to end the inning.

In February 1916 it was announced that Acosta would be sent to the Minneapolis Millers of the Class-AA American Association. Acosta played almost the entire year in Minnesota, returning to Washington only for a five-game stint in July. Unfortunately, the injury bug followed him to the minors. He hurt his leg, and that wiped out the final 42 games of his season and his entire winter league season.

After playing for the Baltimore Orioles in the Class-AA International League for all of 1917, Acosta was farmed out again to start the 1918 season, this time to the Atlanta Crackers in the Class-A Southern League. He was recalled to Washington during the year to replace Sam Rice, who had been called to report for military service. Acosta appeared in only three games, though, before being returned to Atlanta, finishing the season with .224 average over 34 games there. But this time he was traded outright to the Crackers, officially ending his time in the Washington organization. Griffith remained active in the Latin player market for years to come (aided by Joe Cambria), but he had finally moved on from one of his first prospective targets from the area.

That June, Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack needed an outfielder and purchased Acosta’s contract from Atlanta. He made his Athletics debut on June 26, ironically against his former Washington teammates. He went 2-for-4 and scored a run. With Philadelphia Acosta seemed to finally find his stride, something that had eluded him in Washington. Mack figured Acosta could hit as long as he was “permitted to hit in his own style,”13 The approach helped Acosta become one of the surprise performers of the summer. At one point in July, he had the top batting average in the junior circuit, reaching a high mark of .417, though his 48 at-bats was not enough to quality for the league lead.

Yet as productive a season as Acosta had, hitting .298 over 171 at-bats, it was his last in the major leagues. Over the offseason Mack felt his outfield improved with the return of Whitey Witt from military service and the addition of Braggo Roth. Acosta’s services were no longer needed by the Athletics.

While waiting to determine where he might play for the upcoming season, Acosta again returned to Havana for the winter. In a game on December 2, 1918, he took part in another baseball rarity. He completed an unassisted triple play, which is rare enough on its own — but his feat was accomplished as a center fielder. Acosta was playing shallow and caught a line drive, then ran into the infield to step on second base and promptly tag out the runner approaching from first. This rarest-of-rare version of the unassisted triple play has never been accomplished in the majors in the modern era.14

In March 1919 Acosta found his home away from Cuba when the Louisville Colonels of the Class-AA American Association purchased his contract. He remained there for the next decade. During the 1920s he helped future major league manager Joe McCarthy build a powerhouse of the league that won three pennants and upset the Baltimore Orioles in the 1921 Junior World Series (the AA minor league equivalent of the World Series). He batted .350 and scored 135 runs to help the 1921 champions and batted over .300 again for the Colonels in their 1925 pennant winning campaign. Nearly 30 years later he was still remembered as one of the most popular Colonels of all time.15 He was appreciated by fans and teammates in Louisville for his hustle and for his jovial personality, and his popularity did not end there. In 1922 he married the team’s secretary, the former Nancy Lee Bennett. Nancy also happened to be the adopted daughter of Colonels owner William F. Knebelkamp.

It was during this period that Acosta moved into a manager role in the Cuban league. Although he was still only in his twenties while he played in Louisville, he had already developed a knack for player development. He often assisted with coaching the University of Louisville baseball squad or local amateur teams, and he was later credited with having a hand in training young Earle Combs.16 In the 1922-23 winter season, at just 26 years old, he became the first manager of the new Cuban winter team in his hometown of Marianao. Acosta was an easy choice for the role — he was also part-owner of the team. In their first season the team finished first in the league. He served as player-manager for two more winters, often recruiting his Louisville teammates to travel south and join him.

As in his major-league seasons, Acosta continued to suffer injuries during his time in Louisville. He missed most of 1923 after breaking his leg in May and did not return until June the following season. In September 1925 he hurt his back sliding in a game and ended up with a damaged spinal column that later required surgery. This latest injury affected him through the next two seasons, essentially ending his playing career in the winter Cuban league. He finished his 12-year career there with a recorded lifetime batting average of .292.17

Acosta’s back still ailed coming out of spring training 1927; thus. he decided to retire as a player and accept a role as a coach for the Colonels. He was financially secure from business dealings in Cuba, including running a paving business and being involved with a horse track in Marianao. Acosta was an ardent fan of horse racing, another reason for his fondness for Louisville. He even co-owned a horse with Colonels’ owner Knebelkamp, fittingly named Acosta. So he would have been perfectly happy helping coach the team and devoting his remaining time to his side interests.

But in July, Acosta was pressed back into outfield duty for the Colonels. He’d have been better off staying in the coach’s box full time. On August 15, at Louisville’s Parkway Field, Acosta stepped in to face Millers pitcher Pat Malone, whose first offering sailed and struck Acosta in the right ear. He fell unconscious to the ground at the feet of catcher Hank Gowdy, and was rushed to the hospital to undergo surgery for a fractured skull. During Acosta’s stay in the hospital Cuban president Gerardo Machado requested daily wire updates on his condition.18

Acosta made a full recovery, but outside of filling in for 16 games in 1928, he officially retired as a ballplayer. He hoped to transition into managing in the U.S. As luck would have it, Colonels’ owner Knebelkamp needed a skipper for another team he owned, the Dayton Fliers of the Class-B Central League, and Acosta was hired for the position. He managed the team just for the 1929 season, leading the Flyers to a third-place finish. Though his minor-league managing career was short-lived, one of his accomplishments at Dayton was helping to work with 19-year-old Billy Herman on his way to a Hall of Fame career.19

After leaving Dayton, Merito and Nancy, along with their three sons, moved to Havana so he could focus more on his businesses there. Sad to relate, in March 1933 Nancy died after being stricken with peritonitis during a visit back to Louisville. Their three boys went to live with her sister and brother-in-law back in Louisville. Acosta stayed in Cuba to work on business, and soon politics, but he was a regular visitor to the states to visit his sons.

Acosta started off his political career as Cuban consulate to the United States. In 1938 he was elected to the Cuban House of Representatives. Through both roles Acosta maintained ties to baseball. He was still part owner of the Marianao team, and he worked to set up exhibition tours for major-league teams to come to the country, as well as barnstorming tours for Cuban teams. He also formed a business relationship with his old boss, Clark Griffith, and through him met Joe Cambria, Griffith’s super scout who was especially active in Latin territories.

In March 1946, Acosta was asked to participate in a conference with major-league Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler and other baseball officials to review the structure of Latin American baseball and how Cuba would work with Organized Baseball. (The conference was in response to Jorge Pasquel’s efforts to lure players to his “outlaw” Mexican League.) Just one month before to this conference, it had been announced that Acosta would head up a team in the new Class-C Florida-International league, the first attempt to bring Cuba into Organized Baseball. The Havana Cubans were sponsored by the Washington Senators, with Griffith owning a stake and Cambria helping run the club as the secretary-treasurer. The team was to play home games at La Tropical Stadium, which would be fitted with the first night lighting in a Cuban ballpark.20

The “Cubans” was an appropriate name: their roster was filled with Cuban players, many of them veterans of the winter leagues. Conrado Marrero, the staff ace from 1947 through 1949, was the primary example. He was joined by the other three standout pitchers from the glory years of Cuban amateur baseball: Julio “Jiquí” Moreno, Rogelio “Limonar” Martinez, and Sandalio “Sandy” Consuegra.

The Cubans raised some eyebrows when they won 19 of 20 games to start off their inaugural season, and questions arose about the team’s roster. An investigation in May found that several players on their roster were ineligible according to league roster rules. Acosta claimed the league’s policies had been misinterpreted, but the Cubans were forced to forfeit 17 of their victories.21 Havana still ran away with the league pennant, winning it by seven games, before being upset by West Palm Beach in the league playoffs. The Cubans were the dominant team of the league at its outset, winning the first five pennants (the league ceased operations in July of the 1954 season).

But the Cubans were also beset with controversy during Acosta’s years leading the team. In August 1947 Cambria was investigated for accusations that he may have been paying Cuban players under the table. Cambria was later cleared of the claims, and Acosta was never believed to be involved in the first place, yet the Havana club was still fined $500 for salary violations.22 Acosta spent an interim period in 1948 as league president, and under his direction the status of the Florida-International league was raised a level, to Class-B, in 1949. Yet despite his accomplishments, the controlling group of team stockholders, led by Griffith and Cambria, unceremoniously voted Acosta out as team president on the grounds of team mismanagement.23 (For more on the wrangling among the various stakeholders in the Cubans franchise, see the biography of Bobby Maduro, who eventually bought majority interest in the club.)

Acosta sued in Cuban court, and it was ruled under Cuban law that even though Griffith’s group held more shares of team stock, Acosta and his faction possessed more votes in team decisions.24 Acosta was granted back control of the team, but he did not act on his victory, and the whole experience seemingly ended his interest in being involved in professional baseball. He maintained a minority share in the Cubans franchise, but he concentrated on his other ventures. He continued to hold position in the Cuban congress, and later he established the first greyhound dog racing track in the country. He had remarried in Cuba to Graciela Eugenia Fernández, and they had two young children, Edgar and Grace, which also kept him busy.

Acosta was still active in Cuban politics when Fidel Castro assumed power over Cuba in 1959. Acosta tried to promote baseball as best as he could under the new regime, but he and his family ultimately left the country and relocated to Miami. He was actively involved in anti-Castro efforts from the U.S. when he suffered a heart attack and died on November 17, 1963, at the age of 67. He was interred at Flagler Memorial Park in Miami.

But before he departed Cuba, Baldomero Acosta’s career as a player, manager, executive, and promoter of baseball between his native country and his adopted home in the United States had been recognized in 1955 when he was inducted into the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame.

Acknowledgments

Roberto González Echevarría and Felix Julio Alfonso were both gracious enough to answer any questions I had for them regarding Baldomero Acosta and Cuban baseball. Rory Costello contributed additional items on the Havana Cubans roster and history.

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Coen, Ed. “Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2019, 69-70.

Echevarria, Roberto Gonzalez. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1999).

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: 1878-1961 (North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2007).

Hernandez, Lou. Chronology of Latin Americans in Baseball, 1871-2015 (North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2016).

O’Neal, Bill. The American Association: A Baseball History, 1902-1991 (Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1991).

Smith, Steve. “The Long Forgotten Florida International League”, The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016).

Sugar, Bert and Samelson, Ken. The Baseball Maniac’s Almanac, 5th Edition (New York, NY, Sports Publishing, 2019).

Wilson, Nick C. Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States: Major, Minor, and Negro Leagues, 1901-1949 (North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2005).

SABR bio of Armando Marsans, by Eric Enders.

Minor league stats were taken from The American Association by Bill O’Neal.

www.acostarottweilers.com/mydad is a family site that highlights Merito Acosta’s life with notes and rare family photos.

Notes

1 J. Ed Grillo, “Griffith’s Cuban Recruits Look Like Real Players,” Evening Star, (Washington D.C.), February 2, 1913: 56.

2 “Acosta, Youthful National, Comes from Fighting Stock,” Washington Post, March 16, 1913: 4.

3 Calvo was farmed to Atlanta in August, but he ended up playing over 20 seasons in Cuba and in the minor leagues.

4 William Peet, “Griff’s Cuban Recruit Is Son of Marianao Mayor,” Washington Herald, February 2, 1913: 39.

5 J. Ed. Grillo, “Griffith Signs 16-Year-Old Cuban Outfielder”, Evening Star, January 26, 1913: 53.

6 Grillo.

7 William Peet, “Thousand Fans Greet Nationals at Station,” Washington Herald, July 25, 1913: 8.

8 “Senator”, “Acosta Wants To Go To The Bush,” Washington Times, May 29, 1913: 12.

9 According to The Baseball Maniac’s Almanac, 5th Edition, Acosta was the youngest player to make a debut since Joe Stanley joined the 1897 Washington Senators at the age of 16 years, 6 months. Acosta’s modern era record stood until August 18, 1943, when Roger McKee joined the Philadelphia Athletics at 16 years, 11 months.

10 This was noted in the book Chronology of Latin Americans in Baseball by Lou Hernandez and verified using www.baseball-reference.com.

11 Louis A. Dougher, “Honors Pour Upon Climbers’ Midget,” Washington Times, December 2, 1913: 12.

12 Albert “Bugs” Baer, “Mince Pie (Little Bit of Everything),” Washington Times, June 19, 1915: 11.

13 “Diamond Notes,” Carbondale Daily News (Carbondale, Pennsylvania), August 17, 1918: 7.

14 The SABR Triple Play database shows this feat was completed by outfielder Paul Hines in 1878 for Providence (see SABR’s game story). It has not occurred in the major leagues since.

15 “Ruby’s Report,” Courier–Journal, (Louisville, Kentucky), August 1, 1951: 15.

16 “Merito Acosta, Former Ball Player, Now Cuban Consul,” Associated Press, May 6, 1937.

17 Cuban Winter League statistics taken from Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball by Jorge S. Figueredo.

18 “Cuban President Cables Inquiry About Acosta,” Courier–Journal, August 19, 1927: 15.

19 Jack Gallagher, “Routzong Credits Rickey for His Rise as Executive,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1954: 10.

20 Pedro Galiana, “Havana Will Install Lights for Debut in Organized Ball”, The Sporting News, February 7, 1946: 6.

21 “Minor League Rules Uphold Fla.-Int. Proxy on Forfeits,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1946: 34.

22 John McMullan, “’Whole Club Guilty,’ Havana Fined Record $500 For Salary Violations,” Miami Daily News, August 17, 1947: 10.

23 Guy Butler, “Griff Plans to Unseat Acosta; F-I Moguls Pleased At Change,” Miami Daily News, August 4, 1950: 17.

24 Jimmy Burns, “Griff to Fight Cuban Court Ruling Restoring Acosta as Havana Boss,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1950: 17.

Full Name

Baldomero Pedro Acosta Fernandez

Born

May 19, 1896 at Bauta, (Cuba)

Died

November 17, 1963 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.