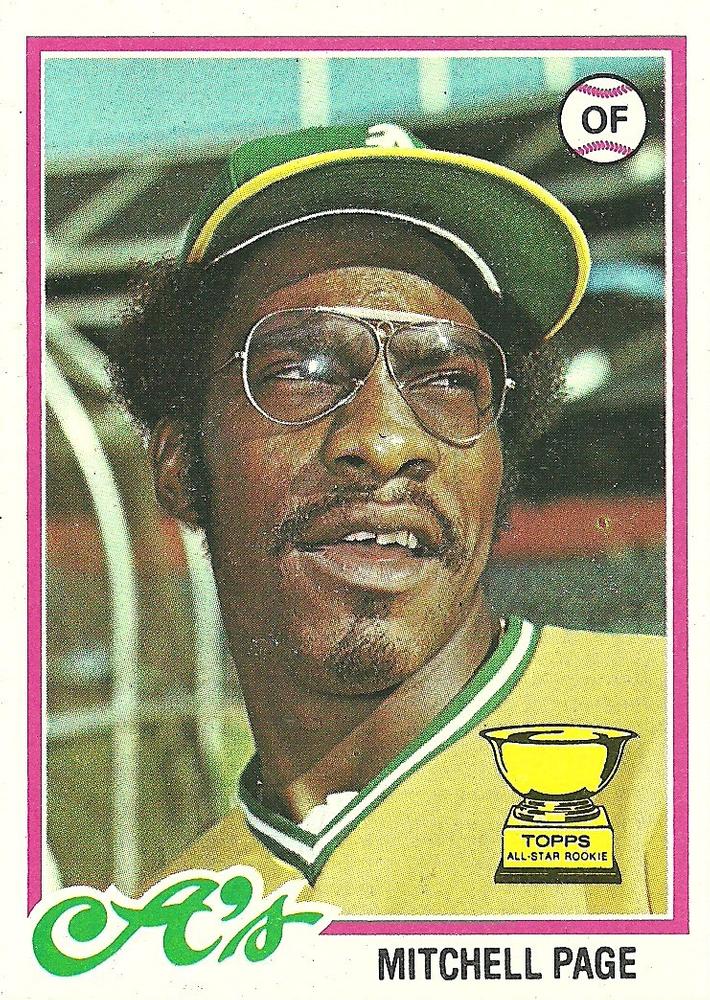

Mitchell Page

In 1977 the original Star Wars hit theaters; Jimmy Carter was sworn in as president; the first Apple II computers went on sale; and New York City lost power and was blacked out for 25 hours. But what most Oakland A’s fans of a certain age remember about that year — an otherwise dismal time in the franchise’s history — is the brilliant rookie season of slugger Mitchell “The Rage” Page. The stars who had led the A’s to three consecutive World Series championships earlier in the decade had departed via trade or free agency. The 25-year-old Page stepped into the gigantic void. He set the American League record for consecutive steals without being caught, was fourth in the league with 6.1 Wins Above Replacement (WAR), and was named Sporting News Rookie of the Year.

In 1977 the original Star Wars hit theaters; Jimmy Carter was sworn in as president; the first Apple II computers went on sale; and New York City lost power and was blacked out for 25 hours. But what most Oakland A’s fans of a certain age remember about that year — an otherwise dismal time in the franchise’s history — is the brilliant rookie season of slugger Mitchell “The Rage” Page. The stars who had led the A’s to three consecutive World Series championships earlier in the decade had departed via trade or free agency. The 25-year-old Page stepped into the gigantic void. He set the American League record for consecutive steals without being caught, was fourth in the league with 6.1 Wins Above Replacement (WAR), and was named Sporting News Rookie of the Year.

Page was never able to match his fine inaugural campaign.1 His production declined over the next three years, and after 1980 he never again reached 100 major-league at-bats in a season before his retirement in 1984. But Page didn’t disappear entirely after his playing days ended. He landed a role in a Hollywood baseball movie; he wrote a book on hitting; and he served as batting coach for several major- and minor-league teams before his untimely death in 2011 at age 59.

Mitchell Otis Page was born on October 15, 1951, in Los Angeles to Artis Page, a machinist, and his wife, Odessa (née Webb).2 Mitchell had two older sisters, Jeannette and Lola; a twin brother, Michael; and a younger sister, Debbie.3 Though Page’s parents separated when he was young, none of his friends knew because his father would come to the house every evening after work to play catch with Mitchell and Michael.4 Page played Little League, American Legion, and Connie Mack baseball growing up, and starred for Centennial High in Compton, patrolling the outfield with fellow future major leaguer Al Cowens.

Oakland selected Page (who batted left and threw right) out of high school in the fourth round of the January 1970 draft. However, he opted not to sign and instead enrolled at Compton Community College. He then transferred to California State Polytechnic University, in Pomona, where he played in 1972 and 1973 alongside his future teammate with the A’s, third baseman Wayne Gross.

“Mitch was a great guy,” said Gross. “We were a one-two punch, he batted third and I batted fourth. We roomed together on college road trips.”5

Both Page and Gross were drafted after their junior seasons in 1973: Page went in the third round to Pittsburgh, while Gross was selected in the ninth round by Oakland. Little did they know that their paths would cross again in a few short years.

Page signed with Pittsburgh and reported first to Salem in the Class A Carolina League, then to Charleston (South Carolina) in the Western Carolinas League, where he got into 18 games for the first-place Pirates and hit .277 before an injury sidelined him for the remainder of the season.6

In 1974 Page returned to Salem and started slowly, hitting .200 before learning the reason for his struggles: He needed eyeglasses.7 “The glasses made a big difference,” said Page. “I was squinting to see. … By the time I could pick up a fastball, it was right on top of me.” With the help of his corrective lenses, Page finished the year with a .296 average and 17 homers.

His strong showing in Salem earned Page a promotion to Shreveport in the Double-A Texas League in 1975, and he was just as good there, hitting .291 with 23 home runs and 90 runs batted in. As a result of his outstanding season, he was named to the Texas League All-Star team.8

Page continued his methodical climb up the minor-league ladder in 1976 as he joined the Triple-A Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies in the International Association. This promotion came with a catch, however. The Pirates wanted prospects Tony Armas, Omar Moreno, and Miguel Diloné to get the bulk of the Charlies’ outfield duty, so manager Tim Murtaugh moved Page to first base. He was initially unhappy and blamed the stress of the change for a slow offensive start. In June, however, he went 14-for-32 with 14 runs batted in over an eight-game stretch, raising his batting average to .306.9

“Yeah, I’m seeing the ball good right now,” said the bespectacled slugger. “I had some bad vibes when I first came to Charleston, but … I’ve adjusted to playing first base instead of the outfield.”10

Page hit .294 with 22 homers and an .860 OPS for the Charlies, earning him a Bulova watch and a trophy as team MVP.11 He was also named the Most Popular Charlie. Despite his slugging and his popularity, however, the call he hoped for from Pittsburgh never came. The Pirates had Al Oliver, Richie Zisk, and Dave Parker in the outfield along with Willie Stargell at first. There were few opportunities for young players; those that were available went to Moreno, Diloné, and Armas, all of whom received call-ups during the 1976 campaign.

That winter Page played in the Venezuelan League for the first time. He had a superb season for Navegantes de Magallanes, hitting .310 with 13 homers, tied for the league lead in the latter category with Bob Oliver. He had 57 RBIs in 63 games as the team’s primary first baseman.

Despite this strong showing, the logjam in Pittsburgh became even more apparent in spring camp in 1977. Page saw little action early, making only five plate appearances through mid-March.12 Then, on March 15, the Pirates and Oakland A’s announced a blockbuster nine-player deal: Pittsburgh received All-Star infielder Phil Garner, veteran utilityman Tommy Helms, and pitcher Chris Batton; Page was sent to the A’s along with Armas and pitchers Dave Giusti, Doc Medich, Doug Bair, and Rick Langford. Page saw the trade as positive. “I thought that I deserved a chance to play in the majors, but I could see I wasn’t getting it with Pittsburgh,” he said.13

The 1977 A’s had lots of job openings. Six veterans — Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace, Rollie Fingers, Sal Bando, Bert Campaneris, and Don Baylor — had exercised the newly granted option of free agency the previous fall and left Oakland for more lucrative pastures. Page took Rudi’s spot in left field, while his former college teammate Gross filled in for Bando.

Page batted third on Opening Day and quickly showed he belonged. In his first major-league at-bat, with fellow newcomer Rodney Scott aboard, Page singled against Minnesota hurler Dave Goltz. He and Scott came around to score on cleanup hitter Dick Allen’s base hit and an error by shortstop Roy Smalley. Page added a walk and another single in the A’s 7-4 win.

Both the A’s and Page continued to play well. On April 13, in support of longtime fellow Pittsburgh farmhand Langford, Page blasted two home runs and a double to drive in six runs in Oakland’s 9-3 victory over the California Angels. Eight games into the season, Page had an eight-game hitting streak and a .500 batting average, while the surprising A’s were 7-1. The baseball world took notice: Famously penurious A’s owner Charlie Finley announced he was increasing Page’s salary 50 percent, to $30,000 a year;14 and the rookie was named American League Player of the Week in his first week in the majors.

The good times lasted only a bit longer for the A’s. At the end of April, they were 12-9, but they would lose nearly two of every three games played the rest of the way, finishing in last place in the American League West. They trailed even the Seattle Mariners, a first-year expansion franchise.

For Page, though, the entire season was a ringing success. He quickly became a popular figure with the Oakland fans, who formed “Page’s Platoon” in the left-field stands, replacing “Reggie’s Regiment” that had once ruled the right-field bleachers.15 A’s play-by-play man Monte Moore dubbed him “The Swinging Rage,” but sportswriters and fans referred to him simply as “The Rage.”

Page’s teammates also thought highly of him. “When I got traded from the Yankees to the A’s [in April 1977], Mitchell was one of the first people I met. He helped me find a place to live,” said former A’s outfielder Larry Murray. “Mitch was like a big brother to us younger guys.”16

Page also had a mischievous side. “He had an identical twin brother, and they liked to pull pranks,” remembered Gross. “One time his brother came into the clubhouse and suited up and everyone thought it was Mitch.”17

In June The Rage was featured on the cover of The Sporting News, a rare honor for a rookie on a losing club.18 He slumped that month as he contended with a painful callus on his hand — but heated up again in July, raising his average back above the .300 mark. On September 2, after an outstanding stretch that included a game with two homers and a triple on national television against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park, he garnered his second Player of the Week award. At season’s end he boasted a slash line of .307/.405/.521. His OPS of .926 was fourth in the league behind only Rod Carew, Ken Singleton, and Jim Rice.

In addition to his consistency at the plate, the 6-foot-2, 205-pound slugger became a more prolific basestealer. He’d swiped 23 in both 1975 and 1976 but reached 42 steals for Oakland. On August 13, when he stole second against Baltimore left-hander Mike Flanagan, it marked his 26th consecutive theft without being thrown out, breaking Don Baylor’s American League record of 25 in a row.19 He was caught only five times that season.

Page’s peers recognized his outstanding season by voting him The Sporting News Rookie of the Year. Unfortunately for him, however, the writers charged with determining the official award winners selected Orioles first baseman Eddie Murray (slash line of .283/.333/.470 and 3.2 WAR) as American League Rookie of the Year with 12 votes against 9 for Page. Oakland fans and many people in baseball felt strongly that the writers had gotten it wrong, a conviction that has only grown over the years as advanced analytics confirmed that Page’s season was far superior to Murray’s. “I was teammates with Eddie Murray for two years in Baltimore at the end of my career, and I tell everybody he was the greatest hitter I ever played with,” said Gross. “Still, I think everybody in the game who watched Mitch play thought he deserved Rookie of the Year in 1977.”20

Shortly after the season ended, Page had surgery on the hand that had troubled him during the year.21 He then played winter ball for Magallanes again before returning and signing a one-year deal with the A’s for $66,000. “With a 120 percent raise I’ll be about the sixth highest paid player on the team, which isn’t bad for a second-year man,” Page said. “I’m very happy. I don’t want to be too greedy.”22

During the offseason, Finley had struck a deal to sell the team to oil magnate Marvin Davis that would have resulted in a move to Denver. A fan interviewed about the looming sale spoke for many A’s followers who had lost interest in the club after the exodus of their stars. “These guys they have left now … who are they, besides Mitchell Page? I don’t think anybody cares.”23

The deal ended up falling apart at the last minute, meaning that the A’s would play at least one more season in Oakland. But regardless of location, the 1978 club didn’t look much different from the 1977 version; once again they fielded a mix of unproven youngsters and mostly over-the-hill veterans.

Page opened the season on the disabled list but returned during a surprisingly strong opening stretch in which the A’s won 19 of their first 24 games to build a four-game lead over the California Angels. In a thrilling win on April 26 (characteristically witnessed by only 4,127 at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum), Page sent the game into extra innings with a two-out, two-strike, game-tying home run in the bottom of the ninth against Minnesota. After the Twins scored two in the 12th to take an 8-6 lead, Page’s single leading off the bottom of the inning sparked a three-run A’s rally for a 9-8 victory.

Oakland was still above .500 and clinging to third place in the division as late as mid-August — but won only eight of its last 41 games to finish a distant sixth. While Page’s .285/.355/.459 slash line was down from his rookie season across the board, he still captured the team’s triple crown, with 17 homers and 70 runs batted in to accompany his .285 batting average.

The offseason was eventful both personally and professionally. In October Page married Nikki Russell in Reno, Nevada.24 He then returned to Magallanes for his third and final season in Venezuela. The Navegantes became league champions and thus qualified for the round-robin Caribbean Series in Puerto Rico, where Page was the leader in home runs (2) and RBIs (11). He was selected the Series’ Most Valuable Player in what he called his biggest thrill in baseball.25

In Page’s view, his production during his first two years with the A’s warranted a six-figure salary in 1979. “I think I have to be guaranteed $100,000,” he said.26 Finley disagreed, offering him a small raise to $70,000. Players had recently won the right to salary arbitration, but what benefited several teammates hurt Page. Not only was he one day short of the service time needed to qualify but also Finley pointed to the five arbitration cases he lost to other players as the reason he was unable to offer Page a bigger increase.27

The Rage was indignant. “There are a few players on this team who hit .230 who are making about $90,000,” he said. When Page announced that he would miss some intrasquad and exhibition games “to relax my mind,” Finley suspended him, cutting off his room-and-board money until he returned to action a few days later.28

Whereas the lowly A’s had started out strong in both 1977 and 1978 before fading, in 1979 they were terrible from the get-go, losing nine of their first 10 contests. Unhappy with his contract and with being made the full-time designated hitter, Page also struggled early and was hitting only .237 with 8 home runs at the All-Star break.29 His most noteworthy accomplishment to that point was an RBI single on June 27 that plated rookie Rickey Henderson, the first of the record 2,295 runs the future Hall of Famer would score in his fabled career.

Frustrated, Page began working with a psychologist to improve his mental approach to the game. Using visualization techniques improved his mental state and, he felt, led to a monthlong hot streak he enjoyed shortly thereafter.30 “I wish I’d started the program at the beginning of the season,” said Page. “The first time I went to a session I had such a negative attitude. … But the process balanced a lot of the negativity with a positive attitude.”31 Page’s work with the psychologist was novel enough that it was featured on the television series That’s Incredible.32 Still, though his final numbers improved a bit late in the season, Page’s slash line of .247/.323/.335 was hardly incredible.

Nevertheless, he sought a raise to $100,000 for 1980 and won his arbitration case against Finley, who had proposed an $85,000 figure. Another positive development was that Finley, aiming to generate some desperately needed excitement around the club, had hired Bay Area native Billy Martin as the new manager. “I love it,” said Page. “We need a lot of discipline. … You do it Billy’s way, or you don’t do it.”33

To the surprise of most sportswriters — but not to Martin — the 1980 A’s got off to a strong start. “Why should I be surprised?” said Martin. “I said in spring training we’d be a good ballclub.”34 Under Martin, the A’s were scrappy and employed exciting — but risky — strategies like suicide squeezes and steals of home. Oakland Tribune sportswriter Ralph Wiley dubbed it “Billy Ball,” a moniker that caught on with the national press.35 Oakland fans, who had stayed away from the Coliseum in droves in 1979, slowly started returning to see what the hoopla was about.

Despite the success of the A’s under Martin, Page wasn’t happy that the manager was using him exclusively as a designated hitter and sitting him against most left-handed pitchers. Page asked for — and was largely given — two weeks off in late July/early August to regain his mental sharpness. When he returned, he went on a home-run tear, hitting 10 homers in 18 games beginning on August 16 in Seattle. “The two weeks off gave me a mental rest and I understand why Billy wants me in this role,” he said. “I am hot now and I hope I can keep going, because I don’t want to let my teammates down.”36

The A’s finished the season second in the American League West with 83 wins, an impressive 29 game year-to-year improvement. While their home attendance of 842,259 was only 12th in the league, it was almost three times the previous year’s total. Positive signs abounded: a winning manager; young stars like Henderson (who’d stolen an American League-record 100 bases) and Mike Norris (who’d won 22 games and finished second in the Cy Young Award vote); and, perhaps most importantly, new ownership. Walter Haas, owner of Levi Strauss, had bought the team from Finley and pledged not only to keep the A’s in Oakland but also to treat them as a community asset.

The Haas family was willing to spend money to retain talent, and they signed several players to long-term contracts that would have been unfathomable under Finley.37 Although Page’s production in 1980 had fallen far short of his rookie totals, his 17 home runs in platoon duty motivated the new owners to offer him a five-year contract for a reported $1.9 million.38

The 1981 A’s got off to a historic start, winning their first 11 games before losing one. Page, however, contributed little: By early June he was batting around .150 with 4 home runs. At that point the A’s, battling for first place in the Western Division, sent him to Triple-A Tacoma “to play every day and get his timing back.”39

Page played well, hitting .328 with 17 homers — and collecting his paycheck, while his former Oakland teammates sat idle most of the summer amid the 1981 players strike. He rejoined the A’s in September but got only three at-bats and did not play in either of the team’s postseason series.

Page opened the 1982 season back in Tacoma. He was called up in midseason and hit .256 with 4 homers in 78 at-bats. He made the major-league club out of spring training in 1983, but played sparingly, hitting .241 with no home runs in 79 at-bats. The A’s bought out the final two years of his contract and released him before the 1984 season.40

Page signed as a free agent with Pittsburgh and made 183 plate appearances for their Triple-A affiliate, Hawaii, before being recalled in August by the Pirates. Appearing exclusively as a pinch-hitter, he was 4-for-12, singling off Cubs pitcher George Frazier for his final major-league hit. Page returned to Hawaii in 1985, making 171 plate appearances before retiring at age 33. His final major-league totals were .266/.346/.429 and 72 home runs in 2,398 plate appearances.

In the early 1990s, Page — by then the father of a young son, Kyle — returned to baseball when Tacoma manager Bob Boone hired him as a coach for the 1992 season.41 In 1994, while still with Tacoma, Page played Angels first baseman Abascal in the Disney feature film Angels in the Outfield. Page’s one line in the film came in response to the suggestion that he and his cinematic teammates needed to work on fundamentals. Ironically for a man working as a baseball coach, his reply was, “Fundamentals? In the middle of the season?”42

When the Kansas City Royals hired Boone as their manager for the 1995 season, he tabbed Page as his first-base coach.43 The Royals had little success under Boone and in July 1997 he was fired, as was Page.44

In 1998, the St. Louis Cardinals hired Page as hitting coach for the Triple-A Memphis Redbirds. The Cardinals’ general manager, Walt Jocketty, and manager, Tony La Russa, both knew him from their days in Oakland.45 The following year he began a stint as a roving minor-league instructor for the organization; in 2000 he worked with a young third baseman at Class A Peoria named Albert Pujols. “He wasn’t happy hitting .330 or .340 in A ball, so I gave him all the work he wanted,” said Page.46

“Mitch taught Pujols how to hit,” Gross said with a laugh.47

In mid-2001, with the Cardinals underperforming at the plate, Page was promoted, replacing Mike Easler as hitting coach. According to Hardball Times, “Page knew how to work with videotape in breaking down his hitters’ swings, diagnosing flaws that needed correcting. He also had the kind of outgoing personality that helped him get through to players. … He was passionate and smart, always a good combination.”48

The Cardinals hitters thrived under Page’s tutelage, finishing in the top two in the league in team batting average and OPS in 2003 and 2004. Professionally, things were going well for him. Off the field, however, it was a different story. Page lived in a suite at the Marriott Hotel in St. Louis and was lonely. He and Nikki had divorced, and Page missed his son, Kyle, by then a teenager.49 At some point, he began drinking heavily.

“It just happened, gradually. … I had always had my beer with the best of them. But when it came to a point where you realize, ‘This is not you’ was when I started drinking vodka.”50

The Cardinals won the National League pennant in 2004 but were swept by the Red Sox in the World Series. At the conclusion of the Series, the Cardinals fired Page owing to his alcohol issues.

Page entered a treatment program immediately after his termination and told a reporter in early 2005 that it had been almost three months since he “divorced” beer and vodka.51 Fortuitously for Page, around that time his former boss Boone was hired by the Washington Nationals as a special assistant and recommended that Page be brought on as minor-league hitting instructor. “So much of hitting is relating with players, and Mitch could always do that,” Boone said. “They respond to him. … Mitch gets them to improve.”52

In 2006 the Nationals promoted Page to hitting coach at the big-league level. That same year, he self-published The Complete Manual of Hitting, a summary of the pointers he’d passed on to hitters as a coach.53 But in May 2007, the Nationals announced that Page was taking a leave of absence “for undisclosed personal reasons.”54 He briefly returned as a roving minor-league instructor later in 2007, then left the Nationals organization. His final job in baseball was back with the Cardinals as a spring-training instructor in 2010.

On March 12, 2011, Page died in his sleep at his home in Arizona. He was just 59 years old. No official cause of death was given.

For fans who had followed and cheered for “The Rage” when he exploded on the baseball scene in 1977, the news of his death hit hard. In one representative online tribute, Ben Mankiewicz of Turner Classic Movies wrote, “Mitchell Page was a huge part of my life, casting a shadow nearly as large as any friend or family member. … When I read he’d died this weekend, I felt a degree of sadness I suspect is reserved for just this situation — for boys who learn their favorite player, the object of their passion and love of a game, was gone.”55

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

Venezuelan statistics courtesy of pelotabinaria.com.ve.

Notes

1 Bill James, “The 25 Most Disappointing Rookies of All Time,” Bill James Online, billjamesonline.com/disappointments_and_surprises_ii, accessed December 20, 2022. James defined them as rookies who “fell significantly short of the careers that we would have expected them to have, based on their rookie seasons.”

2 Ancestry.com.

3 Mitchell Page Oral History (2002), https://sabr.org/?s=Mitchell+Page&post_type%5Binterview%5D=interview. Accessed January 16, 2023.

4 Mitchell Page Oral History.

5 Wayne Gross, telephone interview with the author, September 7, 2022 (hereafter Gross interview).

6 Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Mitchell Page.

7 Rick Woodson, “Glasses Make Swatting Cinch for Shreveport Slugger Page,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1975: 39.

8 “Weese Named to Team,” San Antonio Express, July 22, 1975: 30.

9 Bill Smith, “Charlies May Be in Cellar, but They Have Pride, Too,” Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, June 2, 1976: 19.

10 Smith, “Charlies May Be in Cellar, but They Have Pride, Too.”

11 Bill Smith, “Charleston Charlies Just Couldn’t Win for Losing,” Charleston Daily Mail, September 1, 1976: 22.

12 Tom Weir, “A’s Flip Their Lid Over Gilt-Edged Page,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1977: 3.

13 John Hickey, “Page Lives Up to Prediction as A’s Win,” Fremont (California) Argus, April 14, 1977: 17.

14 Hickey, “Page Lives Up to Prediction as A’s Win”; Bill Hodge, “Baseball, Economy Style,” San Mateo (California) Times, July 19, 1977: 18.

15 Weir, “A’s Flip Their Lid Over Gilt-Edged Page.”

16 Larry Murray, telephone interview with the author, March 29, 2022.

17 Gross interview.

18 “Steal of a Deal? Mitchell Page, Oakland A’s,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1977: 1.

19 Page’s streak ended at 26 a couple of days later when Cleveland left-hander Rick Waits caught him leaning and picked him off, with Page thrown out at second.

20 Gross interview.

21 United Press International, “Minor Surgery Set for Mitchell Page,” Cumberland (Maryland) News, October 7, 1977: 21.

22 United Press International, “A’s Open Camp, Ink Mitchell,” Ukiah (California) Daily Journal, February 23, 1978: 6.

23 United Press International, “Mixed Feelings on A’s Sale,” Fremont Argus, December 16, 1977: 29.

24 Nevada US Marriage Index, accessed on Ancestry.com.

25 Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Mitchell Page.

26 Tom Weir, “Page Expects to Be on A’s Block,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1978: 16.

27 Associated Press, “A’s New Problem: Page Suspended,” Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel, March 8, 1979: 36.

28 “A’s New Problem: Page Suspended.”

29 Michael Levy, “The Video Coach,” Professional Sports Journal, October 1979: 52 (accessed in Mitchell Page Hall of Fame file).

30 Levy, “The Video Coach.” See also Bob McCoy, “Keeping Score,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1980: 6.

31 Levy, “The Video Coach.”

32 “That’s Incredible” segment, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrQtYheE0No, accessed January 6, 2023. The segment aired on March 9, 1981, according to TV listings in the San Bernardino County (California) Sun, March 8, 1981: 111.

33 Tom Weir, “A’s Remind Martin of His Rangers Club,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1980: 20.

34 Associated Press, “Martin and A’s on Top,” Ottawa (Ontario) Journal, April 23, 1980: 22.

35 Dale Tafoya, Billy Ball: Billy Martin and the Resurrection of the Oakland A’s (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), 89.

36 United Press International, “Page Happy to be A’s DH, Thanks to Billy Martin,” Ukiah Daily Journal, September 10, 1980: 62.

37 Tafoya, Billy Ball, 159. Rick Langford got the biggest contract, six years at $600,000 a year. Others signing multiyear deals included Page, catcher Jeff Newman, and pitcher Matt Keough.

38 Tafoya, Billy Ball, 159.

39 Associated Press, “A’s Send Page to Minors,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, June 9, 1981: 18.

40 Kit Stier, “Quirks in Schedule Disgruntle A’s,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1984: 16.

41 Kit Stier, “Oakland,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1991: 41.

42 “Angels in the Outfield (1994). Mitchell Page: Abascal — Angels Player.” IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109127/characters/nm0656285, accessed January 15, 2023.

43 “Baseball Insider: Kansas City Royals,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1994: 50.

44 Associated Press, “Royals Fire Boone,” Paris (Texas) News, July 9, 1997: 8.

45 Brian Walton, “Former Cardinals Hitting Coach Mitchell Page Dies at 59,” Cardinal Nation, March 13, 2011, https://thecardinalnation.com/former-cardinals-hitting-coach-mitchell-page-dies-at-59/, accessed January 21, 2023.

46 Matt Crossman, “Sweet Swing of Success,” The Sporting News, June 23, 2003: 21.

47 Gross interview.

48 Bruce Markusen, “The Sudden Death of Mitchell Page,” Hardball Times, March 14, 2011, https://tht.fangraphs.com/tht-live/the-sudden-death-of-mitchell-page/, accessed January 21, 2023.

49 Joe Strauss, “Mitchell Page: ‘I Screwed Up,’” STLToday.com, January 16, 2005. Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Mitchell Page.

50 Barry Svrluga, “Turning a New Page,” Washington Post, March 4, 2005. Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Mitchell Page.

51 Strauss, “Mitchell Page: ‘I Screwed Up.’”

52 Svrluga, “Turning a New Page.”

53 Amazon.com, https://www.amazon.com/Complete-Manual-Hitting-Mitchell-2006-01-17/dp/B01FEPKJ60/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_product_top?ie=UTF8, accessed January 21, 2023.

54 Tarik El-Bashir, “Page Granted Personal Leave, Expected Back,” washingtonpost.com, May 12, 2007. Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Mitchell Page.

55 Ben Mankiewicz, “Mitchell Page: What to Do When Your Boyhood Hero Dies,” huffingtonpost.com, March 14, 2011. Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Mitchell Page.

Full Name

Mitchell Otis Page

Born

October 15, 1951 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

March 12, 2011 at Glendale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.