June 12, 1967: Paul Casanova’s hit ends baseball’s longest night in 22nd inning

“It’s true, ladies, all true. THE game did last almost until dawn’s early light and your old man was not out on the town, even if he may have looked it.”—Morris Siegel1

“It’s true, ladies, all true. THE game did last almost until dawn’s early light and your old man was not out on the town, even if he may have looked it.”—Morris Siegel1

Open any book about baseball or any page on the SABR website to reveal myriad ways to contemplate the game. Consider that baseball is in part a game of numbers and statistics, and, more recently, one of analytics. Baseball has also been characterized as a game of failure where a good hitter fails nearly 70 percent of the time. Errors are meticulously identified and tracked.

The course of the game is largely determined by the batter in the box, the pitcher on the mound, and the position players in the field, all without the benefit of a clock. We expect the outcome to be resolved in nine innings. When it is not, then the endurance of the players, to say nothing of the fans, becomes increasingly important.

Mix all of these elements together while exploring what actually happened at the ballpark on a night they played a 22-inning game in the nation’s capital. One writer described it as “alternately suspenseful, boring, daring, conservative, routine and unusual.”2

The Washington Senators had returned home to D.C. Stadium from Boston after a 12-game road trip, having just split a doubleheader with the Red Sox. One weekend earlier, they had lost two consecutive extra-inning games in Baltimore in 11 and 19 innings, respectively.3 Feats of endurance in preparation for the longest night? Meanwhile, the Chicago White Sox had already endured three doubleheaders in June but managed to sweep one at Yankee Stadium and move into first place in the American League before heading to Washington to play the Senators.

Perhaps fitting for a Monday night game in front of a small crowd (7,236), the pitching matchup featured two Joes—Joe Horlen for the White Sox and Joe Coleman for the Senators. Horlen (7-0, 2.13 ERA) was on his way to the only All-Star selection of his 12-season career. He had already beaten the Senators twice in April.4 The 20-year-old Coleman (3-4, 5.16 ERA) was still getting his feet wet in his rookie season.5

The White Sox started quickly against Coleman. Walt Williams opened the game with an infield single and advanced to third when Don Buford singled to right. Williams scored when Tommie Agee grounded into a 5-4-3 double play, and the White Sox held a 1-0 lead. Ken Berry grounded out to end the first and Coleman had to feel relieved after allowing two hits to start the game.

The Senators had only Mike Epstein’s second-inning single to show for their offense in the first three innings against Horlen. Epstein was playing his first game as a Senator at D.C. Stadium since being traded from the Baltimore Orioles two weeks earlier.6

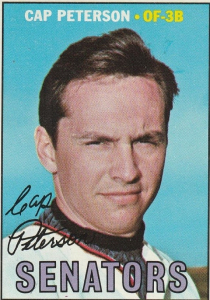

The Senators finally broke through in the fourth with successive solo home runs by Frank Howard and Cap Peterson for a 2-1 lead. Howard’s 16th home run was his fifth in five games, placing him right behind Baltimore’s Frank Robinson (18) for the major-league lead. An early-season slump and unkind booing by fans were behind the massive (6-feet-7, 255-pounds) right-handed hitter, and a change in his batting stance was starting to pay dividends.7

Peterson came to bat again against Horlen in the sixth inning with two outs and Bob Saverine on first and hit his second home run of the game to widen the lead to 4-1. That was enough for White Sox manager Eddie Stanky to replace Horlen with Don McMahon to get the final out of the inning.

Meanwhile, Coleman had the White Sox well under control through the first six innings. Tommy McCraw had opened the second with a single to left but was picked off first with Pete Ward batting. The White Sox didn’t get another hit until the fifth, when Ron Hansen’s two-out double to left was of no consequence.

The three induced Chicago groundouts that followed in the sixth inning would belie what was about to happen to Coleman in the seventh. With one out, Ken Berry walked, McCraw’s single to right sent him to third, and Ward walked to load the bases.

Hansen’s single to center scored Berry and McCraw, and Coleman’s night was over in favor of reliever Dick Lines. When Jerry McNertney singled to center, scoring pinch-runner Al Weis, the score was tied, 4-4.

There remained only one more scoring opportunity for either team in regulation. In the bottom of the eighth, Senators pinch-hitter Tim Cullen walked and advanced to second on a sacrifice by Saverine. There he remained after White Sox reliever Wilbur Wood retired Fred Valentine on a fly ball and Hank Allen on a groundout.

As in the very first inning, the bats of Williams and Buford were at it again in the 10th. With one out, Williams’s double and Buford’s single produced a go-ahead run. But the Senators responded in kind with some help from White Sox relief pitcher Bob Locker. Ken McMullen opened the score-or-lose 10th with an infield single. With Jim King pinch-hitting for Ed Brinkman, Locker threw two successive wild pitches and McMullen was now on third with only one out. That was costly. King hit a sacrifice fly to center, scoring McMullen, and the game was tied again.8

The game plodded along. In fact, from the 11th inning through the 19th, the Senators did not have a runner left on base. The White Sox had their chance in the 16th, but with the bases loaded and one out, Berry was caught trying to steal home.

Fast-forward to the 20th inning and a golden opportunity for the Senators to win the game. White Sox relief pitcher John Buzhardt was already into his sixth inning of work. Valentine opened with a single to center before Buzhardt struck out Hank Allen. On a 2-and-2 count, Peterson’s single to right advanced Valentine to third.

Stanky then decided the best strategy was to intentionally walk Epstein to load the bases. It worked! Paul Casanova, hitless in seven at-bats, grounded into a double play, third-to-home-to first. Would the Senators get another chance like that one? Yes, an almost identical one!

In the 22nd inning, Buzhardt, now in his eighth inning of work, walked Allen with one out and again Peterson followed with a hit-and-run single to right advancing Allen to third.

Stanky stuck to his strategy. He walked Epstein again to load the bases. When Casanova singled to left, Berry was playing so shallow that he threw to second hoping to start another double play.9 No such luck. Allen crossed the plate. Game over at 2:43 A.M.

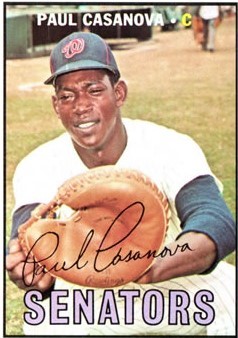

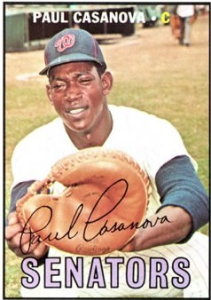

Casanova’s hit ended the 6-hour 38-minute marathon, which at the time was the longest night game in AL/NL history in both innings played and time consumed.10 He had avoided the dreaded O-fer in his ninth and final at-bat.11

In fact, Casanova had a premonition about that hit. Phil Wood, a native Washingtonian and former radio/television sports-talk host, shared a conversation. “Hank Allen told me years ago that Casanova predicted before the start of the bottom of the 22nd that he’d drive in Hank with the winning run.”12

Casanova’s performance was the very definition of endurance. The soon-to-be-named All-Star was behind the plate for all 268 pitches delivered by six different Senators pitchers. Two plays by Casanova in extra innings stand out. Berry tried but failed to steal home in the 16th and Casanova, known for his strong arm, threw out Williams trying to steal second in the 17th inning. Years after the game, Casanova recalled, “The reason the game went so long was because of my defense.”13

For this game, long into the night and early morning hours, the stats were plentiful and the record book a mark of endurance for all 39 players who saw action. Remarkably, neither team committed an error, the longest game in major-league history without a miscue. Well, not exactly. In all the excitement, Senators manager Gil Hodges forgot to send pitcher Barry Moore home early to rest. As the next night’s starter for the Senators, Moore had charted all of those pitches.14

Epstein established two American League fielding records for first baseman—34 chances without an error and 32 putouts in a game.15 Statistical oddities? On offense, Peterson led all players with four hits—two home runs and two timely singles. On defense, Peterson patrolled right field, but not a single fly ball was hit his way for any of the Senators’ 66 putouts.16

As for the endurance of the 1,500 fans left in the ballpark at the game’s conclusion, not everyone saw the winning run cross the plate. Stadium workers had to go through the stands and “shake some snoozers” before going home themselves.17 Good night—or maybe good morning is more appropriate!

Author’s note

What about the patience of the fans and their families over the course of baseball’s longest night? Sportswriter Morris Siegel, writing for Baseball Digest with his typical quick wit and sense of humor, shared the unintended consequences of the late hour.18 Telephones rang at local area police departments and the Washington Senators public-relations department with queries from unbelieving families. Did the game really last until 2:43 A.M.?

Siegel spared no one, not even Bob Humphreys, the winning pitcher with three hitless innings. “[Hodges] had a notion that Bob Humphreys, who has not been going too well, was something of a night owl who rarely fared well before curfew.”19 We can only surmise whether all of Siegel’s stories are really true or just tinged with the humor of the circumstance. Does it really matter?

Acknowledgments

This essay was reviewed by Phil Wood, fact-checked by Bruce Slutsky, and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com (baseball-reference.com/boxes/WS2/WS2196706120.shtml), Retrosheet.org (retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1967/B06120WS21967.htm), and Baseball Almanac (baseball-almanac.com/recbooks/rb_1bpu.shtml) were accessed for box scores/play-by-play information and other data. The Paul Casanova (#115) and Cap Peterson (#387) baseball cards are from the 1967 Topps series and were obtained from the Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Morris Siegel, “The Longest Night,” Baseball Digest, August 1967: 14.

2 Bob Addie, “Nats Go Home with Milkman; 6-Hour Frolic,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1967: 40.

3 On June 3, 1967, the Orioles beat the Senators, 3-2, on Paul Blair’s single in the 11th inning. The next day the Orioles beat the Senators again, 7-5, on Andy Etchebarren’s two-run home run in the 19th inning. See Gary Sarnoff, “June 4, 1967: 5 hours and 18 minutes later, Orioles beat Senators in 19 innings,” SABR Baseball Games Project.

4 Horlen beat the Senators 7-3 with a complete-game performance at White Sox Park on April 16 for his first win of the season. On April 22 he won his second game by pitching a 1-0 two-hitter against the Senators at D.C. Stadium.

5 Horlen finished the season with a 19-7 record, an American League-best 2.06 ERA, with a major-league-leading six shutouts. The All-Star finished second to Jim Lonborg for the American League Cy Young Award. Coleman was the third overall pick in the 1965 amateur draft after the Oakland Athletics picked Rick Monday and the New York Mets selected Les Rohr.

6 On May 29, 1967, the Senators traded pitcher Pete Richert to the Baltimore Orioles for Epstein and pitcher Frank Bertaina.

7 Bob Addie, “Howard Starts Slugging in Reply to Fan Booing,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1967: 40.

8 Ironically, King was traded to the White Sox three days later for Ed Stroud. He was heartbroken. See his biography written by SABR author Andrew Sharp.

9 Merrell Whittlesey, “It Was a Long, Long, Long Happy Night,” The Senators’ Official 1968 Yearbook: 46.

10 “Senators Score in 22-Inning Game,” New York Times, June 13, 1967: 58.

11 Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 589. “Descriptive of a batter who fails to get a hit in any number of at-bats in a game or series of games.” Tommie Agee went 0-for-8 for the White Sox in this game.

12 Phil Wood, email to author, August 6, 2022.

13 José I. Ramirez and Rory Costello, “Paul Casanova,” SABR Baseball Biography Project.

14 Bob Addie, “Nats Go Home with Milkman; 6-Hour Frolic,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1967: 40. How did Moore fare? He gave up six runs in six innings of work as Tommy John pitched a three-hit shutout to beat the Senators, 6-0.

15 On April 13, 1982, California Angels first baseman Rod Carew tied both AL records with 32 putouts, 2 assists, and no errors when the Angels beat the Seattle Mariners, 4-3, in 20 innings.

16 Whittlesey.

17 Whittlesey, 45.

18 Siegel. (William Gildea, “Veteran Sportswriter Morris Siegel Dies at 78,” Washington Post, June 3, 1994, washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1994/06/03/veteran-sportswriter-morris-siegel-dies-at-78/2b7fdd90-5976-413d-ab5e-bf53a6621da2/).

19 Siegel.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 6

Chicago White Sox 5

22 innings

D.C. Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.